Abstract

DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) constitute one of the most dangerous forms of DNA damage. In actively replicating cells, these breaks are first recognized by specialized proteins that initiate a signal transduction cascade that modulates the cell cycle and results in the repair of the breaks by homologous recombination (HR). Protein signaling in response to double strand breaks involves phosphorylation and ubiquitination of chromatin and a variety of associated proteins. Here we review the emerging structural principles that underlie how post-translational protein modifications control protein signaling that emanates from these DNA lesions.

Keywords: double-strand break signaling, phosphorylation signaling, ubiquitin, BRCT domains, FHA domains, Ubc13, UIM

1. Introduction

Diverse forms of genotoxic agents, such as ionizing radiation, reactive oxygen species, and chemotherapies can lead to the generation of single and double stranded breakages in the DNA backbone. Double stranded breaks (DSBs)1 can also arise when a replicating polymerase stalls upon encounter with a damaged DNA template, resulting in dissociation of the polymerase from the replicative helicase and rearrangement of the fork structure in a process termed replication fork collapse [1-2]. DSBs are among the most lethal DNA lesions as just a single DSB left unrepaired can cause chromosomal rearrangements and genomic instability.

In actively replicating cells, DSBs can often be repaired in a largely error-free process via homologous recombination (HR), utilizing the undamaged sister chromatid and much of the same cellular machinery that is used during meiotic recombination [1-2]. Efficient HR repair serves as an effective block to tumourigenesis, as mutations in key players in this pathway, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, can lead to dramatically enhanced cancer risks [3-4]. In addition, since radiotherapy and many DNA-targeted chemotherapies inhibit tumor progression through generation of DSBs, the selective sensitization of tumor cells to these lesions has gained attention as a route to new cancer therapies [5].

DSB repair by HR relies on a cascade of protein-protein interactions that mediates chromosomal structural changes, regulation of the cell cycle, and ultimately recruitment of the HR machinery [6-9]. In this review we focus on the structural principles that have been uncovered that govern how protein phosphorylation and ubiquitination events control protein signaling interactions within this pathway. It should be noted that other pathways, especially non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), are also critical for DSB repair and the reader is referred to recent reviews on this topic [10-11].

2. Overview of protein signaling in the response to DNA double strand breaks

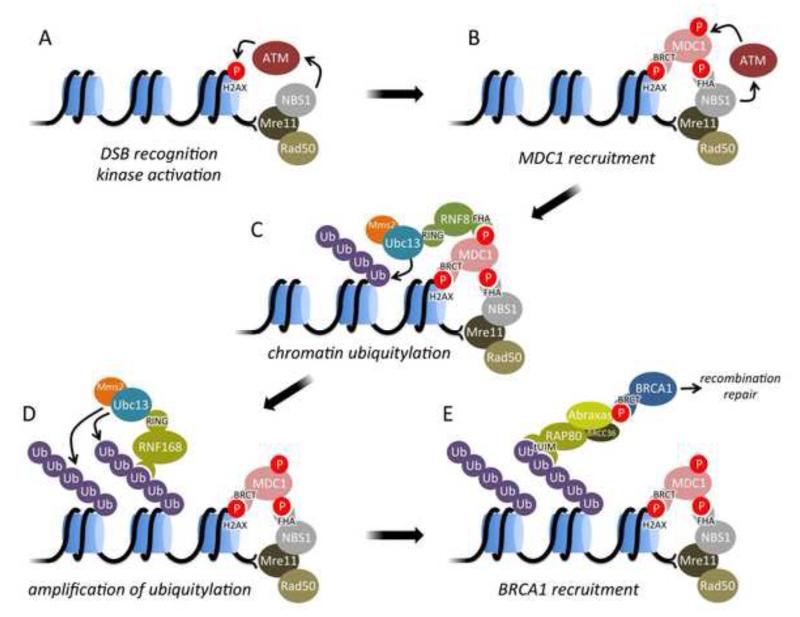

Protein signaling events that emanate from DSBs initiate with specialized protein complexes that recognize the severed ends of the DNA (Fig. 1). The major protein complex thought to recognize DSBs to trigger the HR repair pathway is the MRN (Mre11-Rad50-NBS1) complex, a hetero-hexameric complex that can directly recognize a single DSB or a pair of DSBs to potentiate synapsis (Fig. 1A). A series of elegant structural studies are beginning to reveal how DNA binding and ATPase hydrolysis within the Rad50 subunit induce conformational changes that ultimately drive initiation of DSB signaling [12-19]. Through mechanisms that are still poorly understood, MRN then activates the PI3 kinase ATM, which phosphorylates SQ/TQ sites, to initiate the first steps in DSB signalling. One of the best-characterized and earliest targets of ATM is the histone H2A variant, H2AX, which contains a C-terminal tail not found in H2A [20-21]. Phosphorylation of the H2AX tail (to yield the variant γH2AX) provides a docking site for the next critical protein in DSB signaling, MDC1 (Fig. 1B) [22-24]. MDC1 itself is also phosphorylated by CK2 at a series of SDT sites near its N-terminus that bind the NBS1 component of MRN, thereby enhancing retention of MRN at chromatin near the DSB [25-28]. MDC1 is also phosphorylated at distinct sites by ATM/ATR to provide a binding site for the next protein in the pathway, RNF8 (Fig. 1C) [29-31]. RNF8 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that partners with the E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme Ubc13 to tag H2A/H2B histones near the DSB with polyubiquitin chains. Ubc13 in complex with its partner, Mms2, is a novel E2 that builds polyubiquitin chains that are connected by isopeptide bonds between the ε-amino group of Lys63 of one ubiquitin and the C-terminal carboxylate of the next ubiquitin in the chain [32-37]. RNF8 is not the only E3 involved in generating these chains. A second E3, RNF168, has also been identified in this process (Fig. 1D). Mutation of RNF168 has been implicated in a human immunodeficiency and radiosensitivity disorder termed the RIDDLE syndrome [38]. Initial work indicated that RNF168 acts after RNF8 in the pathway, potentially targeting chromatin regions that were already polyubiquitinated via the RNF168 ubiquitin interacting motifs (UIMs) [39-41]. More recently however, it has been suggested that RNF168 may also play a role in the initial targeting of ubiquitin onto H2A or H2AX in chromatin [40]. The generation of Lys63-linked polyubiquitin is also regulated by a deubiquitinating enzyme, OTUB1, which directly binds and inhibits Ubc13 activity to down-regulate DSB signaling [43-46]. Interestingly, RNF8 also plays a role in the generation of Lys48-linked polyubiquitin near DSBs, which likely is involved in the proteasome-dependent turnover of proteins near the DSB [47].

Fig. 1.

Overview of signaling from DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) to initiate repair by homologous recombination (HR). Phosphorylation events are indicated by red circles, ubiquitylation by purple circles and the domains mediating protein-protein interactions (BRCT, FHA, tUIM, RING) are highlighted.

While the effects of Lys63 polyubiquitylation on chromatin structure have not been determined, it appears that a critical function of these chains is to further recruit other protein complexes to chromatin. The major protein that recognizes these chains in the DNA damage response is RAP80, which contains a novel tandem UIM domain that specifically recognizes at a minimum Lys63-linked diubiquitin (Fig. 1E) [48-50]. More recently, RAP80 has also been shown to bind to ubiquitin chains that also contain the ubiquitin-like protein SUMO via an additional SUMO-interacting motif in RAP80. Critical to the assembly of the ubiquitin-SUMO hybrid chains is another E3 ligase, RNF4, which binds SUMO and links new ubiquitin molecules to pre-existing SUMO chains [51]. RAP80 itself exists as a complex with at least two other proteins, the deubiquinating enzyme BRCC36 and another protein, Abraxas [52-55]. Abraxas does not contain known functional domains but is phosphophorylated at a likely cyclin-dependent kinase site in its C-terminal tail to form a binding site for the breast and ovarian cancer associated protein, BRCA1 (Fig. 1E). BRCA1 can also exist in at least two other complexes; one with the nuclease-associated protein, CtIP [56-57], and the other with the Fanconi anemia-associated helicase, FancJ (also known as BACH1/BRIP1) [58-59]. BRCA1 is thought to be critical for the establishment of HR repair, although the biochemical and structural mechanisms by which this occurs are yet to be elucidated. Part of BRCA1 function likely involves its interaction with PALB2, which could recruit BRCA2 and the HR machinery [60-62]. The N-terminal region of BRCA1 adopts a heterodimeric E3 ubiquitin with another protein partner, BARD1, however the role of this ligase in the HR pathway remains unclear [63-64].

3. Phosphorylation signaling – recognition of phosphate marks by BRCT and FHA domains

The response to DNA double strand breaks initiates with phosphorylation events, largely triggered by PI3 kinases ATM and ATR. In general these phosphorylations create binding sites for specific phospho-peptide recognition protein modules. In the DNA double strand break response, the most common and important modules that mediate these interactions are the BRCT and FHA domains.

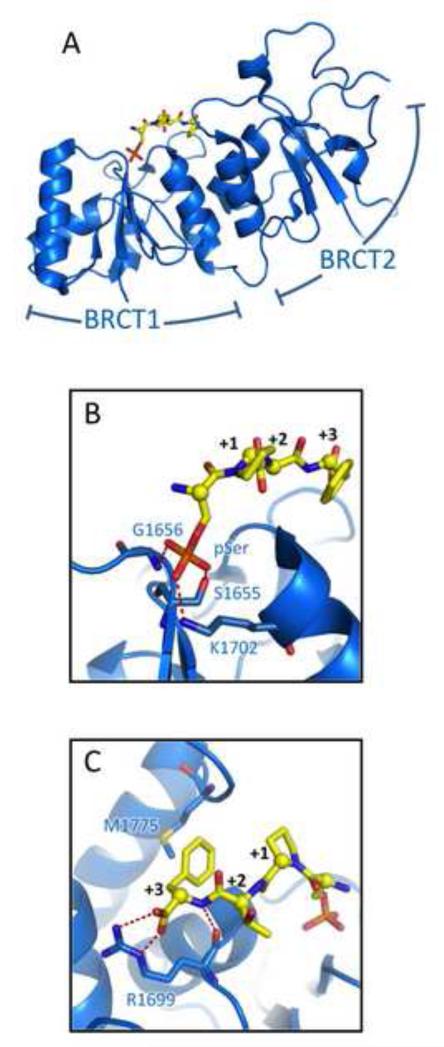

3.1. The BRCT domain (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Phospho-peptide recognition by BRCT domains. (A) Structure of the BRCA1 BRCT domain (blue) bound to a pSer-x-x-Phe target peptide (yellow) with the two tandem BRCT domains indicated. (B) Details of pSer recognition by the BRCA1 BRCT. (C) Details of recognition of the Phe +3 residue and C-terminal carboxylate. Note that the MDC1 BRCT uses a similar mechanism to recognize the C-terminus of γH2AX.

BRCT domains are 90-100 amino acid domains first identified at the C-terminus of BRCA1 [65-66], where they are essential for the tumour suppressor function of the protein [67-68]. BRCT domains often occur as a pair of tandem repeats that pack together in a head to tail arrangement (Fig. 2A) [69]. Shortly after the demonstration that these tandem domains function as phospho-peptide modules [59,70], a series of studies demonstrated that the tandem BRCT domains of both BRCA1 and MDC1 bind their phospho-peptide targets though a similar mechanism [24,71-79]. In general, these proteins recognize phospho-serine/phospho-threonine residues via a conserved phosphate binding pocket in the N-terminal repeat that provides ligands for the phosphate oxygen atoms (Fig. 2B) [68,80]. The BRCA1 and MDC1 BRCTs bind the phosphorylated residue in an orientation that favors pSer binding over pThr, due to steric effects of the pThr methyl group [81]. In addition, these proteins also specifically recognize a Phe/Tyr at the +3 position with respect to the pSer (Fig. 2C) [59,70]. This recognition is via a hydrophobic cleft formed at the interface of the two BRCTs. Interestingly, this pSer-x-x-Phe/Tyr peptide motif is positioned at the C-terminus of both the MDC1 target, γH2AX, as well as the BRCA1 target, Abraxas. Both BRCA1 and MDC1 directly recognize the peptide C-terminal carboxylate via a salt bridging interaction from a conserved arginine residue, which significantly enhances binding affinity [72].

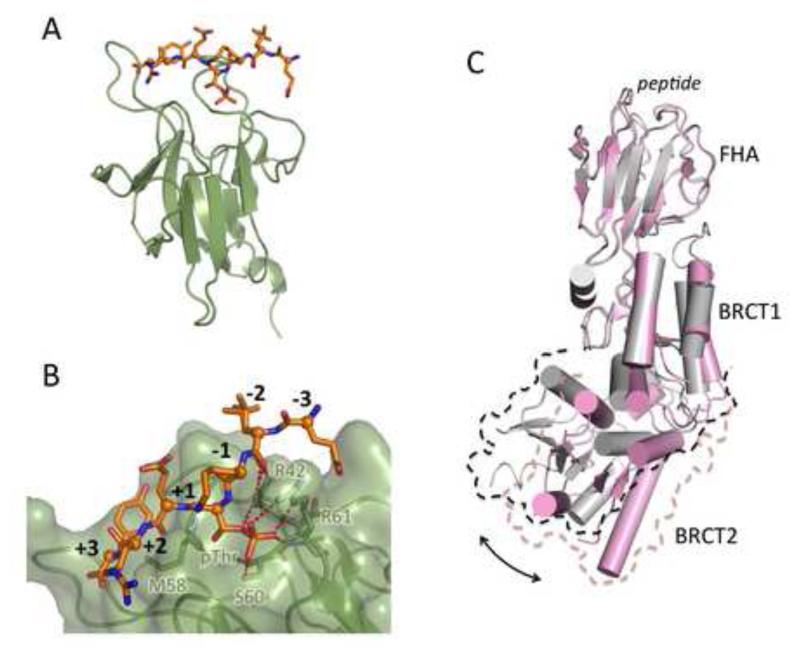

3.2. FHA domain – phosphopeptide interactions (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3.

Phospho-peptide recognition by FHA domains. (A) Structure of the FHA domain of RNF8 (green) bound to its pThr-containing target peptide (orange). (B) Detailed view of the recognition of the pThr and neighboring residues by the RNF8 FHA. (C) Phospho-peptide binding by the NBS1 FHA domain drives a conformational change that leads to a rearrangement of BRCT-BRCT packing. Structure of the NBS1 FHA-BRCT-BRCT domain bound to a CtIP peptide is in pink, while the apo structure is in grey. The structures were aligned on their FHA domains to reveal the resulting rotation of the C-terminal BRCT with respect to the rest of the structure.

FHA domains, initially identified as a signaling domain in certain Forkhead transcription factors [82], are phospho-peptide binding modules that fold into a β-sandwich structure in which the phospho-threonine containing peptide is bound by loops protruding from one edge of the β-sandwich (Fig. 3A) [83]. FHA domains are found in MDC1 [84-86], Nbs1 [87-89], and RNF8 [29] where they are essential for critical phospho-peptide interactions. In contrast to BRCT domains that recognize both pSer- and pThr-containing sequences, FHA domains recognize only pThr-containing targets.

The structure of the RNF8 FHA bound to an optimized pThr peptide provides a general model for FHA target interactions (Fig. 3A) [29]. FHA domains recognize the pThr through a conserved pocket that provides hydrogen-bonding and salt-bridging ligands for the phosphate (Fig. 3B) [88]. Specificity for the pThr is provided by a small hydrophobic pocket that specifically recognizes the γ-methyl of the pThr [90]. Like BRCT peptide recognition, the RNF8 FHA also shows strong selectivity for a Phe/Tyr residue at the +3 position, and the structure reveals a small hydrophobic pocket that contacts this residue [29]. The MDC1 FHA domain appears to recognize an internal, N-terminal ATM phosphorylation site, stabilizing the self-association of MDC1 FHA in response to phosphorylation [84,85].

Intriguingly, the NBS1 FHA domain does not exist as an isolated domain but instead is found as part of a larger fusion of the N-terminal FHA with a tandem BRCT repeat [87,89,91]. Structures of the NBS1 FHA-BRCT-BRCT with target peptides from CtIP [87,89] reveal the conserved recognition of the pThr residue by the FHA, as well as recognition of the neighboring aspartate. However, peptide binding appears to trigger a conformational change that initiates from binding-induced alterations in the FHA peptide binding surface that result in a rotation of the C-terminal BRCT domain with respect to the rest of the structure (Fig. 3C) [89]. This conformational change could present a mechanism by which binding at the FHA ultimately controls subsequent phospho-peptide recognition at the BRCT. The pThr-Asp FHA target sequence revealed in this structural work is likely recognized in a similar way as the pSer-Asp-pThr-Asp MDC1 sequence that is also recognized by this protein [26,84-85,87,89].

4. Generation and recognition of Lys-63 – linked polyubiquitin in DSB signaling

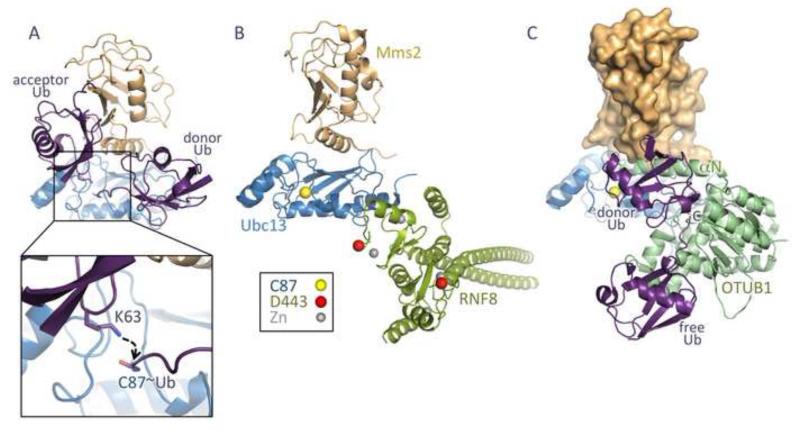

4.1. Generation of Lys63-linked polyubiquitin by Mms2-Ubc13

Early structures of human Mms2-Ubc13 [36] and the closely related S. cerevisiae Uev1a-Ubc13 complex [37] revealed that Mms2 and Uev1a adopt an E2-like fold, although lacking the active site cysteine that characterizes true E2 enzymes. Mms2 binds to a hydrophobic patch on Ubc13 distant from the catalytic cysteine and not conserved in other E2s, explaining why only Ubc13 participates with Mms2 to build Lys63 polyubiquitin. Further NMR and crystallographic work [32,34-35] revealed that Mms2 provides a binding site for an acceptor ubiquitin in an orientation such that its Lys63 is positioned to attack the thioester of the acceptor ubiquitin at the Ubc13 active site (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Structure and regulation of Mms2-Ubc13. (A) Mms2 (orange) binds an acceptor ubiquitin (purple) such that its Lys63 is positioned to attack the thioester of the donor ubiquitin bound to the active site Cys87 of Ubc13 (blue). (B) RNF8 RING domain exists as a coiled-coil – stabilized dimer (green) and binds to Ubc13. Highlighted in red is Asp443, which regulates the ability of the RING domain to target nucleosomes for ubiquitination. (C) OTUB1 (green) binds Ubc13~Ub, blocking RNF8 access and interfering with Mms2 binding to Ubc13. In this figure, Mms2 (orange surface) is docked onto Ubc13 to illustrate the predicted clash with the N-terminal OTUB1 helix (αN). OTUB1 binding is allosterically regulated through the binding of free ubiquitin.

4.2. RNF8 and RNF168 ubiquitin ligases in DSB signaling

Mms2-Ubc13 alone only slowly makes polyubiquitin chains but the rate of chain formation is greatly enhanced by RNF8 [30-31,92-93]. Structural studies have revealed that the RNF8 RING domain adopts the zinc finger fold found in other RING E3 ligases [92,94] (Fig. 4B). However, a striking novel structural feature of RNF8 is its long coiled-coil immediately N-terminal to the RING domain, which is critical for dimerization, as well as binding and activation of Mms2-Ubc13 [92]. The RNF8 RING binds a surface on Ubc13 that appears to be a largely conserved E3 binding site in other E2 enzymes [94-96]. In contrast, RNF168 RING domain does not appear to have the same coiled-coil structure, and the crystallized RNF168 RING construct is in fact a monomer [42,92,97]. The RING domain of RNF168 does not interact tightly with Ubc13 and is much less efficient in the stimulation of Ubc13 activity [92,97]. Recent data have suggested that RNF168 may play an important role in linking the initial ubiquitin molecule to H2A within nucleosomes [42]. This work suggests that single positively charged residue (Arg57) exposed on the surface of the RNF168 RING domain mediates this specificity [42]. The analogous residue in RNF8 is negatively charged (Asp443) providing an explanation for the finding that only RNF168 and not RNF8 can monoubiquitinate nucleosomes in vitro.

4.3. Regulation of Ubc13 by OTUB1

Lys63-linked chain building is also subject to repression via a mechanism that appears to be sensitive to feedback inhibition from the free ubiquitin pool in the cellular milieu of the DSB. Central to this mechanism is OTUB1, a deubiquitinase (DUB) enzyme initially isolated via its association with ovarian cancer [98-99]. OTUB1 specifically binds and hydrolyzes Lys48-linked polyubiquitin using its active site cysteine, which attacks and hydrolyzes the isopeptide ubiquitin-ubiquitin linkage [100]. Intriguingly, the functional active site of OTUB1 is not required to inhibit Ubc13. Instead, OTUB1 inhibits Lys63-linked chain formation through direct interactions with Ubc13 [44-45] (Fig. 4C). These interactions are stabilized by interactions with free ubiquitin as well as donor ubiquitin linked to the Ubc13 active site [43,46]. Structural studies of these complexes [43,46] reveal that the donor ubiquitin binds an otherwise disordered N-terminal segment of OTUB1 in a manner that is facilitated by binding of a second, free ubiquitin. Complex formation likely represses Lys63-linked chain formation in at least three ways. First, binding of OTUB1 occludes the RNF8 docking site on Ubc13, which would reduce efficiency and could facilitate dissociation of Ubc13 from the DSB. Second, the N-terminal helical segment and non-covalent ubiquitin could partially sterically block Uev1/Mms2 binding to Ubc13. Finally, the orientation of the covalently linked, donor ubiquitin may be such that it is less reactive to attack from the incoming lysine of the acceptor ubiquitin. Support for this comes from a recent structure of an E2 enzyme-ubiquitin conjugate with a bound E3 ligase [101-102]. This work indicates that E3 ligases may interact with the donor ubiquitin to hold the ubiquitin in a conformation that enhances the reactivity of the thioester. The OTUB1-Ubc13~Ub structures reveals an alternative conformation that may instead stabilize the thioester to inhibit chain formation.

4.4. Recognition of Lys63 polyubiquitin by RAP80

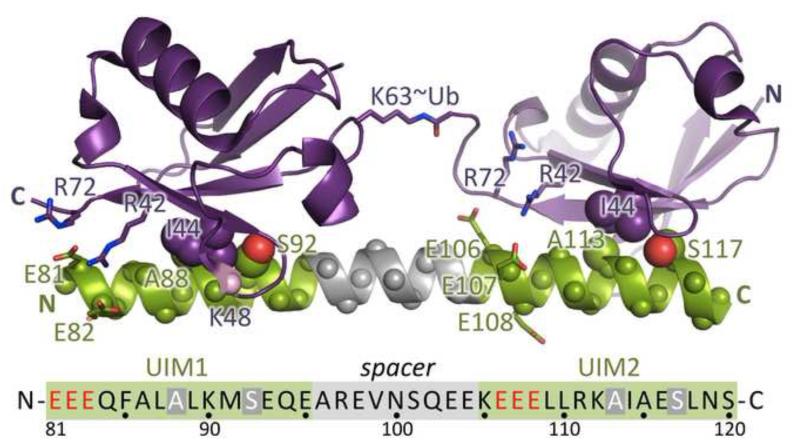

An array of helical motifs and domain structures have been identified that specifically recognize ubiquitin and participate in ubiquitin-mediated signaling [103]. One of the simplest and best studied is the UIM (ubiquitin interacting motif) that adopts a single helix that binds to the hydrophobic face of the ubiquitin β-sheet centered on Ile44. In general, single UIM domains bind weakly to single ubiquitin units with KD’s >100 μM [104]. In DSB signaling, RAP80 specifically recognizes Lys63 polyubiquitin through a novel tandem UIM motif [48-50] (Fig. 5). Biophysical and structural studies have revealed that both UIMs engage individual ubiquitins in model Lys63-linked diubiquitin [48-50]. Specificity for Lys63-linked diubiquitin is achieved through the linkage of the two UIMs [48-50]. Upon binding diubiquitin, this region adopts a helical structure so that the entire UIM is a single contiguous helix. This helical structure positions the two ubiquitin binding surfaces on the same side of the helix and at the correct distance to allow cooperative binding of the diubiquitin. Binding affinities of model UIMs oscillate as linker size is increased in phase with the helical repeat, providing support for this model [48-50]. Lys48-linked chains cannot adopt the extended structure of the Lys63-linked chains, and this likely explains the fact that these chains are bound with much lower affinity [49]. The picture may be even more complex has it has been recently shown that RAP80 also contains a binding motif for the small, ubiquitin-like protein, SUMO, and that RAP80 can bind with <0.2μM affinity to hybrid Lys63-linked ubiquitin/SUMO chains [51,105].

Fig. 5.

Recognition of Lys63-linked di-ubiquitin by the RAP80 tandem UIM (tUIM). The tUIM is shown in green and grey and the sequence of the human RAP80 tUIM is displayed below. Conserved acidic residues in the tUIM and the positively charged residues in ubiquitin with which they interact are shown as sticks. The conserved Ala-Ser residues in the tUIM and Ile44 in ubiquitin that make hydrophobic contact are displayed as spheres.

5. Future challenges in the structural study of DSB signalling

While significant advances have been made in understanding the structures and biochemical functions of isolated components of DSB signalling, we lack structural data that integrates these components into a larger functional framework. Part of the challenge is that many of the signalling proteins involved are enormous (2000 residues or more) and are thought to be highly flexible and post-translationally modified. There have been some recent successes, most notably advances in our understanding of MRN structure and function (section 2), however how MRN interacts with and activates PI3 kinases is still poorly understood. The recent successes in the crystallization and low resolution structure determination of the PI3 kinase family member, DNA-PKcs gives some hope that this question will ultimately be amenable to structural analyses [106]. Another major challenge is to visualize these signalling interactions in the context of nucleosomal structures, to understand the larger impact of these interactions on chromatin structure and dynamics [107]. Many of these challenges will involve the use of hybrid structural methods, incorporating X-ray crystallography with other methods such as electron microscopy or small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) that can be more amenable to the study of large flexible complexes.

Finally, the structural analyses of DSB signalling interactions could provide key information for the rational design of small molecule inhibitors of this system. While the interactions that have been detailed here are not classically “druggable”, there have been some successes. For example, small molecule inhibitors of Ubc13 have recently been isolated that repress NF-κB signalling (which depends on Ubc13-dependent Lys63-linked polyubiquitylation) and inhibit the proliferation of lymphoma cell lines that depend on NF-κB activity [108]. In addition, there have also been reported small molecule and peptidic inhibitors of interactions between the BRCA1 BRCT domain and its phospho-peptide targets [109-110] and these inhibitors can sensitize human cells to PARP inhibition [111]. This provides support for the notion that selective inhibition of the DSB signalling pathway could provide routes for new cancer therapies.

Highlights.

Double strand break (DSB) signaling is initiated with lesion recognition by MRN

DSB recognition leads to protein kinase activation and H2AX phosphorylation

DSB-linked phosphorylation is specifically recognized by BRCT and FHA domain proteins

phosphorylation leads to modification of chromatin by Lys63-linked polyubiquitin

Lys63-linked polyubiquitin is recognized by RAP80 tUIM and recruitment of BRCA1

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants to J.N.M.G. from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (CCSRI) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations: DSB – double strand break; HR – homologous recombination; MRN – Mre11-Rad50-NBS1; RIDDLE syndrome - radiosensitivity, immunodeficiency, dysmorphic features and learning difficulties; UIM – ubiquitin interaction motif; OTUB – otubain or ovarian tumour domain protein; BRCT – BRCA1 C-terminal domain; FHA – Forkhead-associated domain.

References

- [1].Kasparek TR, Humphrey TC. DNA double-strand break repair pathways, chromosomal rearrangements and cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:886–897. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chapman JR, Taylor MR, Boulton SJ. Playing the end game: DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice. Mol Cell. 2012;47:497–510. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Caestecker KW, Van de Walle GR. The role of BRCA1 in DNA double-strand repair: past and present. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dever SM, White ER, Hartman MC, Valerie K. BRCA1-directed, enhanced and aberrant homologous recombination: mechanism and potential treatment strategies. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:687–694. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.4.19212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhang J. The role of BRCA1 in homologous recombination repair in response to replication stress: significance in tumorigenesis and cancer therapy. Cell Biosci. 2013;3:11. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. Initiating cellular stress responses. Cell. 2004;118:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mohammad DH, Yaffe MB. 14-3-3 proteins, FHA domains and BRCT domains in the DNA damage response. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shiloh Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:155–168. doi: 10.1038/nrc1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yan J, Jetten AM. RAP80 and RNF8, key players in the recruitment of repair proteins to DNA damage sites. Cancer Lett. 2008;271:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jeggo PA, Geuting V, Lobrich M. The role of homologous recombination in radiation-induced double-strand break repair. Radiother Oncol. 101:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang C, Lees-Miller SP. Detection and Repair of Ionizing Radiation-Induced DNA Double Strand Breaks: New Developments in Nonhomologous End Joining. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 86:440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hopfner KP, Craig L, Moncalian G, Zinkel RA, Usui T, Owen BA, Karcher A, Henderson B, Bodmer JL, McMurray CT, Carney JP, Petrini JH, Tainer JA. The Rad50 zinc-hook is a structure joining Mre11 complexes in DNA recombination and repair. Nature. 2002;418:562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature00922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hopfner KP, Karcher A, Craig L, Woo TT, Carney JP, Tainer JA. Structural biochemistry and interaction architecture of the DNA double-strand break repair Mre11 nuclease and Rad50-ATPase. Cell. 2001;105:473–485. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hopfner KP, Karcher A, Shin DS, Craig L, Arthur LM, Carney JP, Tainer JA. Structural biology of Rad50 ATPase: ATP-driven conformational control in DNA double-strand break repair and the ABC-ATPase superfamily. Cell. 2000;101:789–800. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80890-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lammens K, Bemeleit DJ, Mockel C, Clausing E, Schele A, Hartung S, Schiller CB, Lucas M, Angermuller C, Soding J, Strasser K, Hopfner KP. The Mre11:Rad50 structure shows an ATP-dependent molecular clamp in DNA double-strand break repair. Cell. 2011;145:54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lim HS, Kim JS, Park YB, Gwon GH, Cho Y. Crystal structure of the Mre11-Rad50-ATPgammaS complex: understanding the interplay between Mre11 and Rad50. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1091–1104. doi: 10.1101/gad.2037811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Park YB, Chae J, Kim YC, Cho Y. Crystal structure of human Mre11: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Structure. 2011;19:1591–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Williams RS, Moncalian G, Williams JS, Yamada Y, Limbo O, Shin DS, Groocock LM, Cahill D, Hitomi C, Guenther G, Moiani D, Carney JP, Russell P, Tainer JA. Mre11 dimers coordinate DNA end bridging and nuclease processing in double-strand-break repair. Cell. 2008;135:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Williams GJ, Williams RS, Williams JS, Moncalian G, Arvai AS, Limbo O, Guenther G, SilDas S, Hammel M, Russell P, Tainer JA. ABC ATPase signature helices in Rad50 link nucleotide state to Mre11 interface for DNA repair. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:423–431. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, Ivanova VS, Bonner WM. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5858–5868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kinner A, Wu W, Staudt C, Iliakis G. Gamma-H2AX in recognition and signaling of DNA double-strand breaks in the context of chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5678–5694. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Goldberg M, Stucki M, Falck J, D’Amours D, Rahman D, Pappin D, Bartek J, Jackson SP. MDC1 is required for the intra-S-phase DNA damage checkpoint. Nature. 2003;421:952–956. doi: 10.1038/nature01445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Stewart GS, Wang B, Bignell CR, Taylor AM, Elledge SJ. MDC1 is a mediator of the mammalian DNA damage checkpoint. Nature. 2003;421:961–966. doi: 10.1038/nature01446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Stucki M, Clapperton JA, Mohammad D, Yaffe MB, Smerdon SJ, Jackson SP. MDC1 directly binds phosphorylated histone H2AX to regulate cellular responses to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell. 2005;123:1213–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Melander F, Bekker-Jensen S, Falck J, Bartek J, Mailand N, Lukas J. Phosphorylation of SDT repeats in the MDC1 N terminus triggers retention of NBS1 at the DNA damage-modified chromatin. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:213–226. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Spycher C, Miller ES, Townsend K, Pavic L, Morrice NA, Janscak P, Stewart GS, Stucki M. Constitutive phosphorylation of MDC1 physically links the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 complex to damaged chromatin. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:227–240. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Xu C, Wu L, Cui G, Botuyan MV, Chen J, Mer G. Structure of a second BRCT domain identified in the nijmegen breakage syndrome protein Nbs1 and its function in an MDC1-dependent localization of Nbs1 to DNA damage sites. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:361–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wu L, Luo K, Lou Z, Chen J. MDC1 regulates intra-S-phase checkpoint by targeting NBS1 to DNA double-strand breaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11200–11205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802885105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Huen MS, Grant R, Manke I, Minn K, Yu X, Yaffe MB, Chen J. RNF8 transduces the DNA-damage signal via histone ubiquitylation and checkpoint protein assembly. Cell. 2007;131:901–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kolas NK, Chapman JR, Nakada S, Ylanko J, Chahwan R, Sweeney FD, Panier S, Mendez M, Wildenhain J, Thomson TM, Pelletier L, Jackson SP, Durocher D. Orchestration of the DNA-damage response by the RNF8 ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2007;318:1637–1640. doi: 10.1126/science.1150034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mailand N, Bekker-Jensen S, Faustrup H, Melander F, Bartek J, Lukas C, Lukas J. RNF8 ubiquitylates histones at DNA double-strand breaks and promotes assembly of repair proteins. Cell. 2007;131:887–900. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Eddins MJ, Carlile CM, Gomez KM, Pickart CM, Wolberger C. Mms2-Ubc13 covalently bound to ubiquitin reveals the structural basis of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chain formation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:915–920. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hofmann RM, Pickart CM. Noncanonical MMS2-encoded ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme functions in assembly of novel polyubiquitin chains for DNA repair. Cell. 1999;96:645–653. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80575-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lewis MJ, Saltibus LF, Hau DD, Xiao W, Spyracopoulos L. Structural basis for non-covalent interaction between ubiquitin and the ubiquitin conjugating enzyme variant human MMS2. J Biomol NMR. 2006;34:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s10858-005-5583-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].McKenna S, Moraes T, Pastushok L, Ptak C, Xiao W, Spyracopoulos L, Ellison MJ. An NMR-based model of the ubiquitin-bound human ubiquitin conjugation complex Mms2.Ubc13. The structural basis for lysine 63 chain catalysis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13151–13158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Moraes TF, Edwards RA, McKenna S, Pastushok L, Xiao W, Glover JN, Ellison MJ. Crystal structure of the human ubiquitin conjugating enzyme complex, hMms2-hUbc13. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:669–673. doi: 10.1038/90373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].VanDemark AP, Hofmann RM, Tsui C, Pickart CM, Wolberger C. Molecular insights into polyubiquitin chain assembly: crystal structure of the Mms2/Ubc13 heterodimer. Cell. 2001;105:711–720. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00387-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Stewart GS, Panier S, Townsend K, Al-Hakim AK, Kolas NK, Miller ES, Nakada S, Ylanko J, Olivarius S, Mendez M, Oldreive C, Wildenhain J, Tagliaferro A, Pelletier L, Taubenheim N, Durandy A, Byrd PJ, Stankovic T, Taylor AM, Durocher D. The RIDDLE syndrome protein mediates a ubiquitin-dependent signaling cascade at sites of DNA damage. Cell. 2009;136:420–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Doil C, Mailand N, Bekker-Jensen S, Menard P, Larsen DH, Pepperkok R, Ellenberg J, Panier S, Durocher D, Bartek J, Lukas J, Lukas C. RNF168 binds and amplifies ubiquitin conjugates on damaged chromosomes to allow accumulation of repair proteins. Cell. 2009;136:435–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pinato S, Gatti M, Scandiuzzi C, Confalonieri S, Penengo L. UMI, a novel RNF168 ubiquitin binding domain involved in the DNA damage signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:118–126. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00818-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Pinato S, Scandiuzzi C, Arnaudo N, Citterio E, Gaudino G, Penengo L. RNF168, a new RING finger, MIU-containing protein that modifies chromatin by ubiquitination of histones H2A and H2AX. BMC Mol Biol. 2009;10:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mattiroli F, Vissers JH, van Dijk WJ, Ikpa P, Citterio E, Vermeulen W, Marteijn JA, Sixma TK. RNF168 ubiquitinates K13-15 on H2A/H2AX to drive DNA damage signaling. Cell. 2012;150:1182–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Juang YC, Landry MC, Sanches M, Vittal V, Leung CC, Ceccarelli DF, Mateo AR, Pruneda JN, Mao DY, Szilard RK, Orlicky S, Munro M, Brzovic PS, Klevit RE, Sicheri F, Durocher D. OTUB1 co-opts Lys48-linked ubiquitin recognition to suppress E2 enzyme function. Mol Cell. 2012;45:384–397. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Nakada S, Tai I, Panier S, Al-Hakim A, Iemura S, Juang YC, O’Donnell L, Kumakubo A, Munro M, Sicheri F, Gingras AC, Natsume T, Suda T, Durocher D. Non-canonical inhibition of DNA damage-dependent ubiquitination by OTUB1. Nature. 2010;466 doi: 10.1038/nature09297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Sato Y, Yamagata A, Goto-Ito S, Kubota K, Miyamoto R, Nakada S, Fukai S. Molecular basis of Lys-63-linked polyubiquitination inhibition by the interaction between human deubiquitinating enzyme OTUB1 and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBC13. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:25860–25868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.364752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wiener R, Zhang X, Wang T, Wolberger C. The mechanism of OTUB1-mediated inhibition of ubiquitination. Nature. 2012;483:618–622. doi: 10.1038/nature10911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ramadan K. p97/VCP- and Lys48-linked polyubiquitination form a new signaling pathway in DNA damage response. Cell Cycle. 11:1062–1069. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.6.19446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Sims JJ, Cohen RE. Linkage-specific avidity defines the lysine 63-linked polyubiquitin-binding preference of rap80. Mol Cell. 2009;33:775–783. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sato Y, Yoshikawa A, Mimura H, Yamashita M, Yamagata A, Fukai S. Structural basis for specific recognition of Lys 63-linked polyubiquitin chains by tandem UIMs of RAP80. Embo J. 2009;28:2461–2468. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sekiyama N, Jee J, Isogai S, Akagi K, Huang TH, Ariyoshi M, Tochio H, Shirakawa M. NMR analysis of Lys63-linked polyubiquitin recognition by the tandem ubiquitin-interacting motifs of Rap80. J Biomol NMR. 2012;52:339–350. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9614-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Guzzo CM, Berndsen CE, Zhu J, Gupta V, Datta A, Greenberg RA, Wolberger C, Matunis MJ. RNF4-dependent hybrid SUMO-ubiquitin chains are signals for RAP80 and thereby mediate the recruitment of BRCA1 to sites of DNA damage. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra88. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kim H, Huang J, Chen J. CCDC98 is a BRCA1-BRCT domain-binding protein involved in the DNA damage response. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:710–715. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Liu Z, Wu J, Yu X. CCDC98 targets BRCA1 to DNA damage sites. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:716–720. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Wang B, Elledge SJ. Ubc13/Rnf8 ubiquitin ligases control foci formation of the Rap80/Abraxas/Brca1/Brcc36 complex in response to DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20759–20763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710061104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Wang B, Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Zhang D, Smogorzewska A, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ. Abraxas and RAP80 form a BRCA1 protein complex required for the DNA damage response. Science. 2007;316:1194–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1139476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Yu X, Wu LC, Bowcock AM, Aronheim A, Baer R. The C-terminal (BRCT) domains of BRCA1 interact in vivo with CtIP, a protein implicated in the CtBP pathway of transcriptional repression. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25388–25392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Wu-Baer F, Baer R. Effect of DNA damage on a BRCA1 complex. Nature. 2001;414:36. doi: 10.1038/35102118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Rodriguez M, Yu X, Chen J, Songyang Z. Phosphopeptide binding specificities of BRCA1 COOH-terminal (BRCT) domains. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52914–52918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Yu X, Chini CC, He M, Mer G, Chen J. The BRCT domain is a phosphoprotein binding domain. Science. 2003;302:639–642. doi: 10.1126/science.1088753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Zhang F, Ma J, Wu J, Ye L, Cai H, Xia B, Yu X. PALB2 links BRCA1 and BRCA2 in the DNA-damage response. Curr Biol. 2009;19:524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Zhang F, Fan Q, Ren K, Andreassen PR. PALB2 functionally connects the breast cancer susceptibility proteins BRCA1 and BRCA2. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1110–1118. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Sy SM, Huen MS, Chen J. PALB2 is an integral component of the BRCA complex required for homologous recombination repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7155–7160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811159106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Brzovic PS, Keeffe JR, Nishikawa H, Miyamoto K, Fox D, 3rd, Fukuda M, Ohta T, Klevit R. Binding and recognition in the assembly of an active BRCA1/BARD1 ubiquitin-ligase complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5646–5651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0836054100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Brzovic PS, Rajagopal P, Hoyt DW, King MC, Klevit RE. Structure of a BRCA1-BARD1 heterodimeric RING-RING complex. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:833–837. doi: 10.1038/nsb1001-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Callebaut I, Mornon JP. From BRCA1 to RAP1: a widespread BRCT module closely associated with DNA repair. FEBS Lett. 1997;400:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Koonin EV, Altschul SF, Bork P. BRCA1 protein products … Functional motifs. Nat Genet. 1996;13:266–268. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Futreal PA, Liu Q, Shattuck-Eidens D, Cochran C, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, Bennett LM, Haugen-Strano A, Swensen J, Miki Y, et al. BRCA1 mutations in primary breast and ovarian carcinomas. Science. 1994;266:120–122. doi: 10.1126/science.7939630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, Liu Q, Cochran C, Bennett LM, Ding W, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266:66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Glover JN, Williams RS, Lee MS. Interactions between BRCT repeats and phosphoproteins: tangled up in two. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:579–585. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Manke IA, Lowery DM, Nguyen A, Yaffe MB. BRCT repeats as phosphopeptide-binding modules involved in protein targeting. Science. 2003;302:636–639. doi: 10.1126/science.1088877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Botuyan MV, Nomine Y, Yu X, Juranic N, Macura S, Chen J, Mer G. Structural basis of BACH1 phosphopeptide recognition by BRCA1 tandem BRCT domains. Structure. 2004;12:1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Campbell SJ, Edwards RA, Glover JN. Comparison of the structures and peptide binding specificities of the BRCT domains of MDC1 and BRCA1. Structure. 2010;18:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Clapperton JA, Manke IA, Lowery DM, Ho T, Haire LF, Yaffe MB, Smerdon SJ. Structure and mechanism of BRCA1 BRCT domain recognition of phosphorylated BACH1 with implications for cancer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:512–518. doi: 10.1038/nsmb775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Coquelle N, Green R, Glover JN. Impact of BRCA1 BRCT domain missense substitutions on phosphopeptide recognition. Biochemistry. 50:4579–4589. doi: 10.1021/bi2003795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Lee MS, Edwards RA, Thede GL, Glover JN. Structure of the BRCT repeat domain of MDC1 and its specificity for the free COOH-terminal end of the gamma-H2AX histone tail. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32053–32056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Shen Y, Tong L. Structural evidence for direct interactions between the BRCT domains of human BRCA1 and a phospho-peptide from human ACC1. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5767–5773. doi: 10.1021/bi800314m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Shiozaki EN, Gu L, Yan N, Shi Y. Structure of the BRCT repeats of BRCA1 bound to a BACH1 phosphopeptide: implications for signaling. Mol Cell. 2004;14:405–412. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00238-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Varma AK, Brown RS, Birrane G, Ladias JA. Structural basis for cell cycle checkpoint control by the BRCA1-CtIP complex. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10941–10946. doi: 10.1021/bi0509651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Williams RS, Lee MS, Hau DD, Glover JN. Structural basis of phosphopeptide recognition by the BRCT domain of BRCA1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:519–525. doi: 10.1038/nsmb776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Leung CC, Glover JN. BRCT domains: easy as one, two, three. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2461–2470. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.15.16312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Leung CC, Gong Z, Chen J, Glover JN. Molecular basis of BACH1/FANCJ recognition by TopBP1 in DNA replication checkpoint control. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:4292–4301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.189555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Hofmann K, Bucher P. The FHA domain: a putative nuclear signalling domain found in protein kinases and transcription factors. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:347–349. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Liang X, Van Doren SR. Mechanistic insights into phosphoprotein-binding FHA domains. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:991–999. doi: 10.1021/ar700148u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Jungmichel S, Clapperton JA, Lloyd J, Hari FJ, Spycher C, Pavic L, Li J, Haire LF, Bonalli M, Larsen DH, Lukas C, Lukas J, MacMillan D, Nielsen ML, Stucki M, Smerdon SJ. The molecular basis of ATM-dependent dimerization of the Mdc1 DNA damage checkpoint mediator. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3913–3928. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Liu J, Luo S, Zhao H, Liao J, Li J, Yang C, Xu B, Stern DF, Xu X, Ye K. Structural mechanism of the phosphorylation-dependent dimerization of the MDC1 forkhead-associated domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3898–3912. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Wu HH, Wu PY, Huang KF, Kao YY, Tsai MD. Structural delineation of MDC1-FHA domain binding with CHK2-pThr68. Biochemistry. 2012;51:575–577. doi: 10.1021/bi201709w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Lloyd J, Chapman JR, Clapperton JA, Haire LF, Hartsuiker E, Li J, Carr AM, Jackson SP, Smerdon SJ. A supramodular FHA/BRCT-repeat architecture mediates Nbs1 adaptor function in response to DNA damage. Cell. 2009;139:100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Mahajan A, Yuan C, Lee H, Chen ES, Wu PY, Tsai MD. Structure and function of the phosphothreonine-specific FHA domain. Sci Signal. 2008;1:re12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.151re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Williams RS, Dodson GE, Limbo O, Yamada Y, Williams JS, Guenther G, Classen S, Glover JN, Iwasaki H, Russell P, Tainer JA. Nbs1 flexibly tethers Ctp1 and Mre11-Rad50 to coordinate DNA double-strand break processing and repair. Cell. 2009;139:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Pennell S, Westcott S, Ortiz-Lombardia M, Patel D, Li J, Nott TJ, Mohammed D, Buxton RS, Yaffe MB, Verma C, Smerdon SJ. Structural and functional analysis of phosphothreonine-dependent FHA domain interactions. Structure. 2010;18:1587–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Hari FJ, Spycher C, Jungmichel S, Pavic L, Stucki M. A divalent FHA/BRCT-binding mechanism couples the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 complex to damaged chromatin. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:387–392. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Campbell SJ, Edwards RA, Leung CC, Neculai D, Hodge CD, Dhe-Paganon S, Glover JN. Molecular insights into the function of RING finger (RNF)-containing proteins hRNF8 and hRNF168 in Ubc13/Mms2-dependent ubiquitylation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23900–23910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.359653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Plans V, Scheper J, Soler M, Loukili N, Okano Y, Thomson TM. The RING finger protein RNF8 recruits UBC13 for lysine 63-based self polyubiquitylation. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:572–582. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Deshaies RJ, Joazeiro CA. RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:399–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.101807.093809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Bentley ML, Corn JE, Dong KC, Phung Q, Cheung TK, Cochran AG. Recognition of UbcH5c and the nucleosome by the Bmi1/Ring1b ubiquitin ligase complex. Embo J. 2011;30:3285–3297. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Yin Q, Lin SC, Lamothe B, Lu M, Lo YC, Hura G, Zheng L, Rich RL, Campos AD, Myszka DG, Lenardo MJ, Darnay BG, Wu H. E2 interaction and dimerization in the crystal structure of TRAF6. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:658–666. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Zhang X, Chen J, Wu M, Wu H, Arokiaraj AW, Wang C, Zhang W, Tao Y, Huen MS, Zang J. Structural basis for role of ring finger protein RNF168 RING domain. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:312–321. doi: 10.4161/cc.23104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Borodovsky A, Ovaa H, Kolli N, Gan-Erdene T, Wilkinson KD, Ploegh HL, Kessler BM. Chemistry-based functional proteomics reveals novel members of the deubiquitinating enzyme family. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1149–1159. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Evans PC, Smith TS, Lai MJ, Williams MG, Burke DF, Heyninck K, Kreike MM, Beyaert R, Blundell TL, Kilshaw PJ. A novel type of deubiquitinating enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23180–23186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301863200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Wang T, Yin L, Cooper EM, Lai MY, Dickey S, Pickart CM, Fushman D, Wilkinson KD, Cohen RE, Wolberger C. Evidence for bidentate substrate binding as the basis for the K48 linkage specificity of otubain 1. J Mol Biol. 2009;386:1011–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Plechanovova A, Jaffray EG, McMahon SA, Johnson KA, Navratilova I, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Mechanism of ubiquitylation by dimeric RING ligase RNF4. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1052–1059. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Plechanovova A, Jaffray EG, Tatham MH, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Structure of a RING E3 ligase and ubiquitin-loaded E2 primed for catalysis. Nature. 2012;489:115–120. doi: 10.1038/nature11376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Hurley JH, Lee S, Prag G. Ubiquitin-binding domains. Biochem J. 2006;399:361–372. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Fisher RD, Wang B, Alam SL, Higginson DS, Robinson H, Sundquist WI, Hill CP. Structure and ubiquitin binding of the ubiquitin-interacting motif. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28976–28984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Hu X, Paul A, Wang B. Rap80 protein recruitment to DNA double-strand breaks requires binding to both small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) and ubiquitin conjugates. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:25510–25519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.374116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Sibanda BL, Chirgadze DY, Blundell TL. Crystal structure of DNA-PKcs reveals a large open-ring cradle comprised of HEAT repeats. Nature. 2010;463:118–121. doi: 10.1038/nature08648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Price BD, D’Andrea AD. Chromatin remodeling at DNA double-strand breaks. Cell. 2013;152:1344–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Pulvino M, Liang Y, Oleksyn D, DeRan M, Van Pelt E, Shapiro J, Sanz I, Chen L, Zhao J. Inhibition of proliferation and survival of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells by a small-molecule inhibitor of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc13-Uev1A. Blood. 2012;120:1668–1677. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-406074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Lokesh GL, Rachamallu A, Kumar GD, Natarajan A. High-throughput fluorescence polarization assay to identify small molecule inhibitors of BRCT domains of breast cancer gene 1. Anal Biochem. 2006;352(1):135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Lokesh GL, Muralidhara BK, Negi SS, Natarajan A. Thermodynamics of phosphopeptide tethering to BRCT: the structural minima for inhibitor design. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(35):10658–10659. doi: 10.1021/ja0739178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Pessetto ZY, Yan Y, Bessho T, Natarajan A. Inhibition of BRCT(BRCA1)-phosphoprotein interaction enhances the cytotoxic effect of olaparib in breast cancer cells: a proof of concept study for synthetic lethal therapeutic option. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(2):511–517. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2079-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]