Abstract

Regular use of aspirin reduces incidence and mortality of various cancers, including colorectal cancer. Anti-cancer effect of aspirin represents one of the “Provocative Questions” in cancer research. Experimental and clinical studies support a carcinogenic role for PTGS2 (cyclooxygenase-2), which is an important enzymatic mediator of inflammation, and a target of aspirin. Recent “Molecular Pathological Epidemiology” (MPE) research has shown that aspirin use is associated with better prognosis and clinical outcome in PIK3CA-mutated colorectal carcinoma, suggesting somatic PIK3CA mutation as a molecular biomarker that predicts response to aspirin therapy. The PI3K enzyme plays a pivotal role in the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. Activating PIK3CA oncogene mutations are observed in various malignancies including breast cancer, ovarian cancer, brain tumor, hepatocellular carcinoma, lung cancer and colon cancer. The prevalence of PIK3CA mutations increases continuously from rectal to cecal cancers, supporting the “colorectal continuum” paradigm, and an important interplay of gut microbiota and host immune/inflammatory reaction. MPE represents an interdisciplinary integrative science, conceptually defined as “epidemiology of molecular heterogeneity of disease”. Because exposome and interactome vary from person to person and influence disease process, each disease process is unique (the unique disease principle). Hence, MPE concept and paradigm can extend to non-neoplastic diseases including diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic diseases, etc. MPE research opportunities are currently limited by paucity of tumor molecular data in existing large-scale population-based studies. However, genomic, epigenomic, and molecular pathology testing (e.g., analyses for microsatellite instability, MLH1 promoter CpG island methylation, and KRAS and BRAF mutations in colorectal tumors) is becoming routine clinical practice. In order for integrative molecular and population science to be routine practice, we must first reform education curricula by integrating both population and molecular biologic sciences. As consequences, next-generation hybrid molecular biological and population scientists can advance science, moving closer to personalized precision medicine and health care.

Keywords: molecular pathologic epidemiology, systems biology, systems pathology, network medicine, unique tumor principle, translational epidemiology

Introduction: Aspirin as Anti-Cancer Drug

Epidemiologic studies as well as evidence from randomized controlled trials indicates that regular use of aspirin reduces incidence of cancers including colorectal cancer,1-10 and that regular use of aspirin after colorectal cancer diagnosis improves patient outcomes.9-16 Experimental data also highlight an oncogenic role for PTGS2 (cyclooxygenase-2), enzyme central to the inflammatory response and a primary target of aspirin.11,17-22 However, beyond the anti-inflammatory effect of aspirin and its influence on PTGS2, the mechanisms underlying improved outcome associated with regular aspirin use remain unclear. Mechanisms of anti-cancer effect of aspirin represent one of the “Provocative Questions” in cancer research.23,24

Colorectal Cancer: Heterogenous Diseases

Colorectal cancers consist of a group of heterogenous disorders with diverse sets of genetic and epigenetic changes which accumulate during the carcinogenesis process.25-29 Genomic and epigenomic analyses of colorectal cancer have revealed enormous heterogeneity of the disease.30-38 In addition, molecular features and behavior of tumor cells are influenced by host immunity and inflammation39-46 as well as by exposome (a totality of exposures from environment) and interactome (a totality of interactions of various molecules).47 Evidence also suggests variability and continuum of functions of oncogenes, tumor suppressors and passenger genes/mutations.47-52 This vast array of influences on both the initiation as well as progression of colorectal cancers poses a significant challenge to accurately predict the clinical behavior of any given tumor. Essentially, each tumor goes through its own unique pathway to cancer and ultimate killing of host.47 If pathway A (to tumor A) is similar to pathway B (to tumor B) but not to pathway C (to tumor C), we can classify tumors A and B into one subtype, and tumor C into another subtype, using tumor biomarker(s). Tumor biomarkers can help classify molecularly-similar cancers into one subtype or another, to better predict their behaviors and response to therapy.47 Thus, molecular testing of tumors has grown increasingly routine in clinical settings.53-58 In addition to inter-tumor heterogeneity, intratumor heterogeneity adds another layer of complexity,59 which can not only lead to heterogeneous biological behavior, but also a practical issue in tumor molecular testing.

Activating mutations in PIK3CA (official HGNC ID: HGNC:8975, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase, catalytic subunit alpha) are present in many cancer types including colorectal cancer. The prevalence of PIK3CA exon 9 and/or exon 20 hotspot mutations in colorectal cancers is approximately 15-20% in large population-based studies,60-62 and more variable in clinical trials63-67 and other studies.68-82 Studies which used Pyrosequencing assay60,83,84 (which is more sensitive than Sanger sequencing85) generally show higher frequencies of PIK3CA mutations than Sanger sequencing studies.61,62,69,80,86 Considering mutations in other less-commonly mutated exons as well as false negativity in molecular assays (particularly, Sanger sequencing), it is estimated that approximately 20% of colorectal cancers in the general population harbor PIK3CA mutations. Interestingly, the prevalence of PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancer increases continuously from rectum (approximately 10%) to cecum (approximately 25%),62,87 supporting the “colorectal continuum” paradigm,88 and an important interplay of gut microbiota and host response.39,89-93PIK3CA mutation in colorectal cancer is associated with phosphorylated AKT expression,94, phosphorylated RPS6 expression,83 inactive CTNNB1 status,83 VDR (vitamin D receptor) expression,95 and KRAS mutations,60,62,83,96 including codon 61 and 146 mutations.50PIK3CA G>A substitutions are associated with loss of MGMT mismatch repair enzyme.62,83 Associations of PIK3CA mutations with other molecular features such as microsatellite instability (MSI), CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), and BRAF mutations are less consistent.60-62,65,71,83PIK3CA amplification has also been reported.97PIK3CA mutation may predict resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in stage IV colorectal cancer.63,86,98-100 A prognostic role of overall PIK3CA mutation status in colorectal cancer remains uncertain;60,65 however, the presence of coexisting exon 9 and exon 20 mutations may be associated with shorter patient survival,60 which is supported by experimental data.101

Colorectal Cancer PIK3CA Mutation Predicts Response to Aspirin

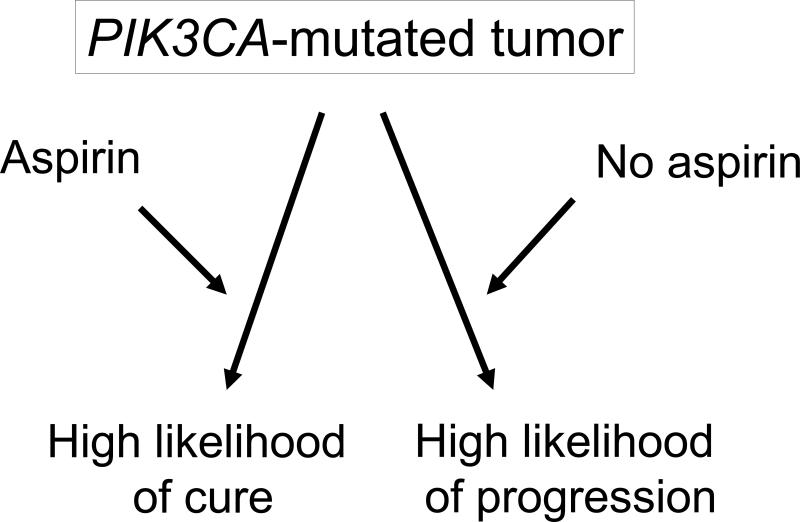

Recently, Liao et al.102 tested the hypothesis that aspirin might be effective specifically on PIK3CA-mutated colorectal cancer, based on experimental evidence for an interplay of the PI3K (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphonate 3-kinase) and PTGS2 (cyclooxygenase-2) pathways.19,103,104 The study demonstrated that the effect of aspirin use on patient survival appeared significantly stronger in PIK3CA-mutated cancer than in PIK3CA-wild-type cancer.102 These findings not only highlight the potential cross-talk between the PI3K and PTGS2 pathways, but also suggest PIK3CA mutation in colorectal cancer as a potential biomarker to predict response to aspirin therapy.102,105,106

Possible Mechanisms of Interaction between Aspirin and Tumor PIK3CA Mutation

The study by Liao et al.102 demonstrated strong interactive effects of aspirin and tumor PIK3CA mutation in a late phase of tumor progression, while the frequencies of tumor PIK3CA mutations were similar in both tumors that arose in aspirin users compared with non-users prior to diagnosis. These data imply that the interactive effect of aspirin and tumor PIK3CA mutation evolves as a tumor develops and progresses. The data also suggest important roles of exposures (including drug) and the tumor microenvironment in modifying a tumor phenotype (Figure 1). Recent evidence attests to the plasticity of BRAF-mutated melanoma cells which is conferred by secretion of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) from stromal cells, leading to tumor resistance to targeted RAF inhibitor therapy.107 In colorectal carcinogenesis, changes in the local tumor microenvironment may also be related to the biogeography of the colon, which could in turn reflect variation in the gut microbiome, an increasingly important area of investigation.

Figure 1.

Outcome of patients with PIK3CA-mutated colorectal cancer appears to differ according to the status of regular aspirin use after cancer diagnosis. The likelihood of long term survival among aspirin users is higher than that among non-aspirin users. The findings suggest that aspirin use may interact with molecular status of tumor to modify a tumor phenotype and clinical behavior.

Accumulating evidence implies a role for gut microbiota and contents in the immune response and carcinogenesis.89-91 In parallel, a recent provocative study showed that the prevalence of major molecular events in colorectal cancer (including PIK3CA and BRAF mutations, microsatellite instability, and CpG island methylator phenotype) appears to increase gradually along detailed subsites from rectum to ascending colon.87 These data challenge the existing dichotomy model of proximal vs. distal colorectum in terms of the molecular features.87,88 Taken together, it is possible that the effect of aspirin on the local microenvironment and its interaction with tumor PIK3CA mutation may change according to gut microbiota, contents, and biogeography.

An alternative mechanism for the interaction between aspirin and tumor PIK3CA mutation may relate to platelet function and tumor thrombosis. The well-characterized anti-platelet effects of aspirin are evident even with low dose of the drug. Distant tumor metastasis consists of a complex process of tumor cell invasion into stroma and vascular wall, survival in the bloodstream, formation of tumor thrombus, attachment of vascular wall at a metastatic site, and tumor cell invasion of the vascular wall into stroma at the metastatic site. Thus, given the central role of thrombosis in tumor metastasis, it is quite plausible that an influence of aspirin on tumor metastatic potential and patient outcomes may be mediated by its anti-platelet effects, which could in turn differ according to PIK3CA mutation status.

What's Next?

Given the intriguing observation by Liao et al.102 what should we do next? First, these findings require validation in independent datasets. Although additional observational and interventional studies would be valuable,108 only a few cohorts have collected detailed long-term data on aspirin use and characterized a substantial number of tumors for PIK3CA mutation. Beyond observational cohort studies, several clinical trials of aspirin as well as the PTGS2 (COX-2) selective inhibitor celecoxib for colorectal cancer patients are underway. Within these studies, the interactive effect of aspirin (or celecoxib) and tumor PIK3CA mutation can be examined. A distinct effect for celecoxib and tumor PIK3CA mutation compared with that for aspirin would support an anti-cancer effect of aspirin mediated through platelets since celecoxib does not appear to significantly inhibit platelets.

Beyond human studies, additional experimental models may be useful to test an interactive effect of aspirin and tumor PIK3CA mutation with the caveat that the local microenvironment in human tumors likely differs from in vitro and animal models.

Thus, for future human correlative studies or experimental systems, it will be increasingly necessary to assess the exposome (a totality of exposures) and interactome (a totality of interactions between various molecules in the local microenvironment). Both molecular pathological epidemiology (MPE) and systems biology109 approaches consider network perturbations beyond a single exposure – molecular pathway interaction in isolation.110

Molecular Pathological Epidemiology (MPE): Integrative Science Enables the Discovery

The study by Liao et al.102 represents a prototypical example of “Molecular Pathological Epidemiology (MPE)” research, which has emerged as the transdisciplinary integration of molecular pathology and epidemiology.43,111,112 The term and concept of MPE have been gaining popularity worldwide.13,92,113-134 Conceptually, MPE is defined as “epidemiology of molecular heterogeneity of disease (both intra-individual and inter-individual)”. Hence, MPE differs from conventional epidemiology where a given disease (eg, colon cancer) is regarded as a single entity without explicit consideration of inherent disease heterogeneity.135 A similar concept of “etiologic heterogeneity” has also been used.136,137 While much of MPE data have been derived from neoplastic diseases, the MPE design and paradigm can be applied to research of non-neoplastic conditions.110 Using MPE design, we can examine interactions between influences of exogenous factors (eg, aspirin use and smoking status) and molecular alterations in cancer (eg, PIK3CA mutation and BRAF mutation), which affect cancer cell behavior.11,102,105,138-140 Thus, much beyond conventional epidemiology research, MPE not only enables further insights into disease development and progression, but also provides potential disease biomarkers which can predict response or resistance to lifestyle or pharmacological intervention.43,112 With conventional epidemiology design, the potential predictive value of PIK3CA mutation in colorectal cancer for response to aspirin could not have been uncovered.

Currently, it requires enormous resources, time and effort to build a database of tumor molecular pathology to make MPE research a reality. Comprehensive database is necessary to assess not only tumor markers, but also various other exposures to control for confounding. In analysis of aspirin use, energy balance status such as body mass index and physical activity may influence systemic inflammation status.141,142 Investigators need to design a study, select populations, follow participants, collect information and biospecimens, and establish an infrastructure for specimen and data management.143 For example, the study by Liao et al.102 utilized databases of longitudinal prospective cohort studies, the Nurses’ Health Study144 and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, which started in 1976 and 1986, respectively. Both studies have not only accumulated enormous amounts of information on diet, lifestyle factors, environmental exposures, and personal and family history of various diseases, but also established repositories of tumor tissues and other biospecimens including blood, buccal cells, toenail and urine. Thus, Liao et al.102 could readily test the intriguing hypothesis of an interactive effect of aspirin and tumor PIK3CA mutation, utilizing this valuable resource. Substantial resources and effort have been devoted to these and other similar large-scale studies, which can help us better understand various diseases and develop effective clinical and public health strategies to decrease disease burden in our societies. Thus, utilization of existing resource can be a very cost effective approach for public health research.145

The MPE concept takes into account the exposome as well as genome, epigenomes, and interactomes in disease pathogenesis. Integration of MPE and systems biology (which typically utilizes experimental model systems) will facilitate the development of new research areas and clinical practice. In line with this integration of MPE and systems biology, nanotechnologies and biosensors can be utilized for improvement of personalized risk stratification, screening, and early detection of diseases.35,146,147

Can MPE Approach Be Used Routinely in Epidemiology Research?

Because most epidemiologic studies and public disease databases lack tumor tissue repositories and molecular data, MPE study designs may be regarded as the exception rather than the rule. MPE has caveats; there is inherent multiple hypothesis testing.112 Because multiple subtypes need to be assessed, sample size in MPE should ideally be large; however, a given MPE dataset is usually confined to existing epidemiologic or clinical cohorts and pathology specimen availability.112 It is well known that many tumor molecular features are associated with each other.25,148-156 Thus, often multiple biomarkers need to be simultaneously assessed. Moreover, to move steps closer to personalized precision medicine, we should be able to address research and clinical questions on less deleterious mutations and mutations in genes which are rarely mutated in a given cancer. All of these factors necessitate large sample sizes in MPE research.

Given the power and promise of MPE research exemplified by Liao et al.,102 how can we facilitate integrative MPE-type research to advance public health science? One near-term solution is the use of non-molecular tumor subtyping, which can reflect tumor molecular biology. For example, colorectal cancer can be classified as fatal cancer vs. non-fatal cancer, which can reflect biological aggressiveness. However, such tumor subtyping is not an optimal classification method since it only captures the behavior of tumor subtypes only to a limited extent.

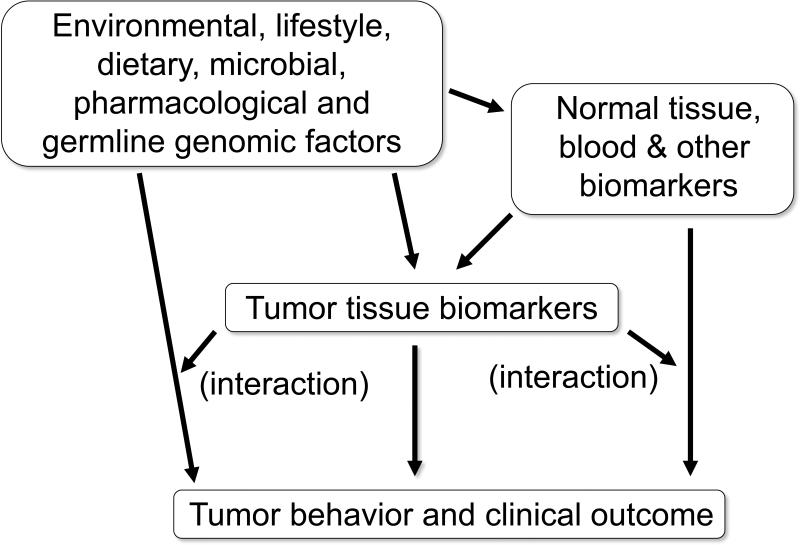

Molecular testing is increasingly routine in colorectal cancer. For example, KRAS mutation testing is common for prediction of resistance to anti-EGFR therapy.55,157,158 MSI and BRAF mutation testing is common for screening of hereditary colorectal cancer.159 More recently, multi-gene testing utilizing next generation sequencing platform is increasingly common. Therefore, it may be possible that population cancer registries can integrate this routine clinical molecular testing data with standard demographic, clinical, and pathological information. Tumor molecular data accumulated in population disease registries will enable investigators to conduct MPE research without necessarily assuming the substantial expense of collecting tissue materials for analysis of tumor molecular changes. Such a population MPE database will be useful to test basic science findings in a population-based human sample,160 towards timely research translation into clinical use. Figure 2 illustrates an example of integrative population-based MPE database, which enables us to readily test a multitude of research hypotheses towards potential translation into clinical and public health practice.

Figure 2.

An example of population-based molecular pathological epidemiology (MPE) database. Such a database enables us to test a multitude of research hypotheses, with a potential for translation into public health and clinical practice.

It may be a challenging task to transform population disease registries into “population molecular pathology registries”. On a basic level, we should introduce MPE concepts within public health schools,125,135,161 so that students can learn not only traditional epidemiologic concepts, but also the molecular pathologic basis of human diseases. This may lead to a new generation of public health practitioners and researchers with a solid understanding of MPE that can lead to effective establishment, development and utilization of population-based molecular pathology registry databases.

As we develop such population molecular pathology registries, additional challenges will emerge. For example, next generation sequencing assays will enable us to sequence an individual's whole exome or genome at a reasonable cost, perhaps as a routine clinical test. Such technology may lead to ready determination of not only the identities of individuals but also the presence of potential known disease-causing mutations that can have profound clinical implications for an individual as well as his/her relatives. How molecular information can or should be accessed in population registries for research remains a significant issue that has yet to be resolved.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

We are moving more towards increasingly interdisciplinary, integrative science. Epidemiology also needs to transform for the new era of medicine and public health.162 The importance of team science and an interdisciplinary education system has repeatedly been discussed.125,133,135,161,163,164 Currently, the MPE study such as the one by Liao et al.102 represents a rare unique example of interdisciplinary research for which a replication study cannot easily be performed. However, in the future it may be possible to transform population disease registries into molecular pathology databases, since molecular testing is increasingly routine in clinical practice. Such population molecular pathology registries will enable investigators to perform MPE research as routine practice. In order to achieve this goal, we should consider introducing MPE concepts within the standard population science training. Providing such an education will hopefully lead to the next generation of population scientists who can firmly understand the principles of MPE and can advance integrative science to move us closer to our goal of personalized medicine and health care.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria.

A comprehensive search for relevant English language publications was performed in Pubmed utilizing Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms, and other terms (“epidemiology”, “cancer”, “tumor”, “molecular pathology”, “molecular pathological epidemiology”, “exposure”, “biomarker”, “aspirin”, “NSAIDs”, “anti-inflammatory drug”, “survival”, “response”), in various combinations. The list of references in retrieved articles was assessed for additional relevant articles. A final decision to include or exclude a given article was based on the quality, relevance, and uniqueness of the article.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants from USA National Institute of Health (NIH) [R01 CA151993 (to SO), R01 CA137178 (to ATC), P50 CA127003 (to CSF), R01 CA124908 (to CSF), P01 CA87969 (to SE Hankinson), and UM1 CA167552 to WC Willett]. ATC is a Damon Runyon Clinical Investigator. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. Funding agencies did not have any role in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication, or the writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: ATC was a consultant of Bayer Healthcare, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer Inc. This work was not funded by Bayer Healthcare, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, or Pfizer Inc. No other conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Algra AM, Rothwell PM. Effects of regular aspirin on long-term cancer incidence and metastasis: a systematic comparison of evidence from observational studies versus randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:518–527. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flossmann E, Rothwell PM. Effect of aspirin on long-term risk of colorectal cancer: consistent evidence from randomised and observational studies. Lancet. 2007;369:1603–1613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60747-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burn J, Gerdes AM, Macrae F, Mecklin JP, Moeslein G, Olschwang S, et al. Long-term effect of aspirin on cancer risk in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer: an analysis from the CAPP2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:2081–2087. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61049-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron JA, Cole BF, Sandler RS, Haile RW, Ahnen D, Bresalier R, et al. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:891–899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandler RS, Halabi S, Baron JA, Budinger S, Paskett E, Keresztes R, et al. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas in patients with previous colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:883–890. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benamouzig R, Uzzan B, Deyra J, Martin A, Girard B, Little J, et al. Prevention by daily soluble aspirin of colorectal adenoma recurrence: 4-year results of the APACC randomised trial. Gut. 2012;61:255–261. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dube C, Rostom A, Lewin G, Tsertsvadze A, Barrowman N, Code C, et al. The use of aspirin for primary prevention of colorectal cancer: a systematic review prepared for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:365–375. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosetti C, Rosato V, Gallus S, Cuzick J, La Vecchia C. Aspirin and cancer risk: a quantitative review to 2011. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1403–1415. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Elwin CE, Norrving B, Algra A, Warlow CP, et al. Long-term effect of aspirin on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: 20-year follow-up of five randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1741–1750. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Price JF, Belch JF, Meade TW, Mehta Z. Effect of daily aspirin on risk of cancer metastasis: a study of incident cancers during randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2012;379:1591–1601. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS. Aspirin use and survival after diagnosis of colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2009;302:649–658. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bastiaannet E, Sampieri K, Dekkers OM, de Craen AJ, van Herk-Sukel MP, Lemmens V, et al. Use of Aspirin postdiagnosis improves survival for colon cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1564–1570. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chia WK, Ali R, Toh HC. Aspirin as adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer-reinterpreting paradigms. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2012;9:561–570. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCowan C, Munro AJ, Donnan PT, Steele RJ. Use of aspirin post-diagnosis in a cohort of patients with colorectal cancer and its association with all-cause and colorectal cancer specific mortality. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zell JA, Ziogas A, Bernstein L, Clarke CA, Deapen D, Largent JA, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: effects on mortality after colorectal cancer diagnosis. Cancer. 2009;115:5662–5671. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coghill AE, Newcomb PA, Campbell PT, Burnett-Hartman AN, Adams SV, Poole EM, et al. Prediagnostic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and survival after diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Gut. 2011;60:491–498. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.221143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsujii M, Kawano S, Tsuji S, Sawaoka H, Hori M, DuBois RN. Cyclooxygenase regulates angiogenesis induced by colon cancer cells. Cell. 1998;93:705–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS. Aspirin and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Relation to the Expression of COX-2. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2131–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markowitz SD. Aspirin and colon cancer--targeting prevention? N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2195–2198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe078044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang D, Xia D, DuBois RN. The crosstalk of PTGS2 and EGF signaling pathways in colorectal cancer. Cancers. 2011;3:3894–3908. doi: 10.3390/cancers3043894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myung SJ, Rerko RM, Yan M, Platzer P, Guda K, Dotson A, et al. 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is an in vivo suppressor of colon tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12098–12102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603235103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xia D, Wang D, Kim SH, Katoh H, Dubois RN. Prostaglandin E(2) promotes intestinal tumor growth via DNA methylation. Nat Med. 2012;18:224–226. doi: 10.1038/nm.2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varmus H, Harlow E. Science funding: Provocative questions in cancer research. Nature. 2012;481:436–437. doi: 10.1038/481436a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam TK, Schully SD, Rogers SD, Benkeser R, Reid B, Khoury MJ. Provocative questions in cancer epidemiology in a time of scientific innovation and budgetary constraints. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:496–500. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogino S, Goel A. Molecular classification and correlates in colorectal cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:13–27. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamiyama H, Suzuki K, Maeda T, Koizumi K, Miyaki Y, Okada S, et al. DNA demethylation in normal colon tissue predicts predisposition to multiple cancers. Oncogene. 2012;31:5029–5037. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asada K, Ando T, Niwa T, Nanjo S, Watanabe N, Okochi-Takada E, et al. FHL1 on chromosome X is a single-hit gastrointestinal tumor-suppressor gene and contributes to the formation of an epigenetic field defect. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Worthley DL, Whitehall VL, Buttenshaw RL, Irahara N, Greco SA, Ramsnes I, et al. DNA methylation within the normal colorectal mucosa is associated with pathway-specific predisposition to cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:1653–1662. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goel A, Boland CR. Epigenetics of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1442–1460. e1441. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, Lin J, Sjoblom T, Leary RJ, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Estecio MR, Gharibyan V, Shen L, Ibrahim AE, Doshi K, He R, et al. LINE-1 hypomethylation in cancer is highly variable and inversely correlated with microsatellite instability. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baba Y, Huttenhower C, Nosho K, Tanaka N, Shima K, Hazra A, et al. Epigenomic diversity of colorectal cancer indicated by LINE-1 methylation in a database of 869 tumors. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:125. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bass AJ, Lawrence MS, Brace LE, Ramos AH, Drier Y, Cibulskis K, et al. Genomic sequencing of colorectal adenocarcinomas identifies a recurrent VTI1A-TCF7L2 fusion. Nat Genet. 2011;43:964–968. doi: 10.1038/ng.936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hinoue T, Weisenberger DJ, Lange CP, Shen H, Byun HM, Van Den Berg D, et al. Genome-scale analysis of aberrant DNA methylation in colorectal cancer. Genome research. 2012;22:271–282. doi: 10.1101/gr.117523.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Q, Dong Y, Wu W, Zhu C, Chong H, Lu J, et al. Detection and differential diagnosis of colon cancer by a cumulative analysis of promoter methylation. Nature communications. 2012;3:1206. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beggs AD, Jones A, El-Bahwary M, Abulafi M, Hodgson SV, Tomlinson IP. Whole-genome methylation analysis of benign and malignant colorectal tumours. J Pathol. 2013;229:697–704. doi: 10.1002/path.4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu Y, Hu B, Choi AJ, Gopalan B, Lee BH, Kalady MF, et al. Unique DNA methylome profiles in CpG island methylator phenotype colon cancers. Genome research. 2012;22:283–291. doi: 10.1101/gr.122788.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fridman WH, Pages F, Sautes-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sidler D, Renzulli P, Schnoz C, Berger B, Schneider-Jakob S, Fluck C, et al. Colon cancer cells produce immunoregulatory glucocorticoids. Oncogene. 2011;30:2411–2419. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dahlin AM, Henriksson ML, Van Guelpen B, Stenling R, Oberg A, Rutegard J, et al. Colorectal cancer prognosis depends on T-cell infiltration and molecular characteristics of the tumor. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:671–682. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edin S, Wikberg ML, Dahlin AM, Rutegard J, Oberg A, Oldenborg PA, et al. The distribution of macrophages with a m1 or m2 phenotype in relation to prognosis and the molecular characteristics of colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogino S, Galon J, Fuchs CS, Dranoff G. Cancer immunology-analysis of host and tumor factors for personalized medicine. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2011;8:711–719. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang D, Dubois RN. The role of COX-2 in intestinal inflammation and colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:781–788. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandez AF, Esteller M. Viral epigenomes in human tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2010;29:1405–1420. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nosho K, Baba Y, Tanaka N, Shima K, Hayashi M, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Tumourinfiltrating T-cell subsets, molecular changes in colorectal cancer and prognosis: cohort study and literature review. J Pathol. 2010;222:350–366. doi: 10.1002/path.2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogino S, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci E. How many molecular subtypes? Implications of the unique tumor principle in personalized medicine. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2012;12:621–628. doi: 10.1586/erm.12.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berger AH, Knudson AG, Pandolfi PP. A continuum model for tumour suppression. Nature. 2011;476:163–169. doi: 10.1038/nature10275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christie M, Jorissen RN, Mouradov D, Sakthianandeswaren A, Li S, Day F, et al. Different APC genotypes in proximal and distal sporadic colorectal cancers suggest distinct WNT/beta-catenin signalling thresholds for tumourigenesis. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imamura Y, Morikawa T, Liao X, Lochhead P, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, et al. Specific Mutations in KRAS Codons 12 and 13, and Patient Prognosis in 1075 BRAF-wild-type Colorectal Cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4753–4763. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McFarland CD, Korolev KS, Kryukov GV, Sunyaev SR, Mirny LA. Impact of deleterious passenger mutations on cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:2910–2915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213968110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen CC, Er TK, Liu YY, Hwang JK, Barrio MJ, Rodrigo M, et al. Computational Analysis of KRAS Mutations: Implications for Different Effects on the KRAS p.G12D and p.G13D Mutations. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lievre A, Blons H, Laurent-Puig P. Oncogenic mutations as predictive factors in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:3033–3043. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sepulveda AR, Jones D, Ogino S, Samowitz W, Gulley ML, Edwards R, et al. CpG methylation analysis--current status of clinical assays and potential applications in molecular diagnostics: a report of the Association for Molecular Pathology. J Mol Diagn. 2009;11:266–278. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2009.080125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Febbo PG, Ladanyi M, Aldape KD, De Marzo AM, Hammond ME, Hayes DF, et al. NCCN Task Force report: Evaluating the clinical utility of tumor markers in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9(Suppl 5):S1–32. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2011.0137. quiz S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lao VV, Grady WM. Epigenetics and colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:686–700. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kitkumthorn N, Mutirangura A. Long interspersed nuclear element-1 hypomethylation in cancer: biology and clinical applications. Clin Epigenet. 2012;2:315–330. doi: 10.1007/s13148-011-0032-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brennan K, Flanagan JM. Is there a link between genome-wide hypomethylation in blood and cancer risk? Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:1345–1357. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marusyk A, Almendro V, Polyak K. Intra-tumor heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:323–334. doi: 10.1038/nrc3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liao X, Morikawa T, Lochhead P, Imamura Y, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, et al. Prognostic Role of PIK3CA Mutation in Colorectal Cancer: Cohort Study and Literature Review. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2257–2268. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barault L, Veyries N, Jooste V, Lecorre D, Chapusot C, Ferraz JM, et al. Mutations in the RAS-MAPK, PI(3)K (phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase) signaling network correlate with poor survival in a population-based series of colon cancers. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2255–2259. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosty C, Young JP, Walsh MD, Clendenning M, Sanderson K, Walters RJ, et al. PIK3CA Activating Mutation in Colorectal Carcinoma: Associations with Molecular Features and Survival. PLoS One. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D, De Schutter J, Biesmans B, Fountzilas G, et al. Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:753–762. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tol J, Dijkstra JR, Klomp M, Teerenstra S, Dommerholt M, Vink-Borger ME, et al. Markers for EGFR pathway activation as predictor of outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with or without cetuximab. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1997–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gavin P, Colangelo LH, Fumagalli D, Tanaka N, Remillard MY, Yothers G, et al. Mutation Profiling and Microsatellite Instability in Stage II and III Colon Cancer: An Assessment of their Prognostic and Oxaliplatin Predictive Value. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6531–6541. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sartore-Bianchi A, Moroni M, Veronese S, Carnaghi C, Bajetta E, Luppi G, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene copy number and clinical outcome of metastatic colorectal cancer treated with panitumumab. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3238–3245. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu S, Gan Y, Wang X, Liu J, Li M, Tang Y. PIK3CA mutation is associated with poor survival among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer following anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody therapy: a meta-analysis. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2013;139:891–900. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1400-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kato S, Iida S, Higuchi T, Ishikawa T, Takagi Y, Yasuno M, et al. PIK3CA mutation is predictive of poor survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1771–1778. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whitehall VL, Rickman C, Bond CE, Ramsnes I, Greco SA, Umapathy A, et al. Oncogenic PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancers and polyps. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:813–820. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abubaker J, Bavi P, Al-Harbi S, Ibrahim M, Siraj AK, Al-Sanea N, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of colorectal cancers with PIK3CA mutations in Middle Eastern population. Oncogene. 2008;27:3539–3545. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Benvenuti S, Frattini M, Arena S, Zanon C, Cappelletti V, Coradini D, et al. PIK3CA cancer mutations display gender and tissue specificity patterns. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:284–288. doi: 10.1002/humu.20648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Farina-Sarasqueta A, van Lijnschoten G, Moerland E, Creemers GJ, Lemmens VE, Rutten HJ, et al. The BRAF V600E mutation is an independent prognostic factor for survival in stage II and stage III colon cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2396–2402. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ollikainen M, Gylling A, Puputti M, Nupponen NN, Abdel-Rahman WM, Butzow R, et al. Patterns of PIK3CA alterations in familial colorectal and endometrial carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:915–920. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.He Y, Van't Veer LJ, Mikolajewska-Hanclich I, van Velthuysen ML, Zeestraten EC, Nagtegaal ID, et al. PIK3CA mutations predict local recurrences in rectal cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6956–6962. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garcia-Solano J, Conesa-Zamora P, Carbonell P, Trujillo-Santos J, Torres-Moreno DD, Pagan-Gomez I, et al. Colorectal serrated adenocarcinoma shows a different profile of oncogene mutations, MSI status and DNA repair protein expression compared to conventional and sporadic MSI-H carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:1790–1799. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Souglakos J, Philips J, Wang R, Marwah S, Silver M, Tzardi M, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of common mutations for treatment response and survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:465–472. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miyaki M, Iijima T, Yamaguchi T, Takahashi K, Matsumoto H, Yasutome M, et al. Mutations of the PIK3CA gene in hereditary colorectal cancers. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1627–1630. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Naguib A, Cooke JC, Happerfield L, Kerr L, Gay LJ, Luben RN, et al. Alterations in PTEN and PIK3CA in colorectal cancers in the EPIC Norfolk study: associations with clinicopathological and dietary factors. BMC cancer. 2011;11:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iida S, Kato S, Ishiguro M, Matsuyama T, Ishikawa T, Kobayashi H, et al. PIK3CA mutation and methylation influences the outcome of colorectal cancer. Oncology letters. 2012;3:565–570. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hsieh LL, Er TK, Chen CC, Hsieh JS, Chang JG, Liu TC. Characteristics and prevalence of KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancer by high-resolution melting analysis in Taiwanese population. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413:1605–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Janku F, Lee JJ, Tsimberidou AM, Hong DS, Naing A, Falchook GS, et al. PIK3CA mutations frequently coexist with RAS and BRAF mutations in patients with advanced cancers. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nosho K, Kawasaki T, Ohnishi M, Suemoto Y, Kirkner GJ, Zepf D, et al. PIK3CA mutation in colorectal cancer: relationship with genetic and epigenetic alterations. Neoplasia. 2008;10:534–541. doi: 10.1593/neo.08336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Garrido-Laguna I, Hong DS, Janku F, Nguyen LM, Falchook GS, Fu S, et al. KRASness and PIK3CAness in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: outcome after treatment with early-phase trials with targeted pathway inhibitors. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Brahmandam M, Yan L, Cantor M, Namgyal C, et al. Sensitive sequencing method for KRAS mutation detection by Pyrosequencing. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:413–421. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60571-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tian S, Simon I, Moreno V, Roepman P, Tabernero J, Snel M, et al. A combined oncogenic pathway signature of BRAF, KRAS and PI3KCA mutation improves colorectal cancer classification and cetuximab treatment prediction. Gut. 2013;62:540–549. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yamauchi M, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Imamura Y, Qian ZR, Nishihara R, et al. Assessment of colorectal cancer molecular features along bowel subsites challenges the conception of distinct dichotomy of proximal versus distal colorectum. Gut. 2012;61:847–854. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yamauchi M, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, Huttenhower C, Chan AT, Giovannucci E, et al. Colorectal cancer: a tale of two sides or a continuum? Gut. 2012;61:794–797. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kostic AD, Gevers D, Pedamallu CS, Michaud M, Duke F, Earl AM, et al. Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome research. 2012;22:292–298. doi: 10.1101/gr.126573.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Castellarin M, Warren RL, Freeman JD, Dreolini L, Krzywinski M, Strauss J, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome research. 2012;22:299–306. doi: 10.1101/gr.126516.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tjalsma H, Boleij A, Marchesi JR, Dutilh BE. A bacterial driver-passenger model for colorectal cancer: beyond the usual suspects. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:575–582. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Galon J, Franck P, Marincola FM, Angell HK, Thurin M, Lugli A, et al. Cancer classification using the Immunoscore: a worldwide task force. Journal of translational medicine. 2012;10:205. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cho I, Blaser MJ. The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:260–270. doi: 10.1038/nrg3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Baba Y, Nosho K, Shima K, Hayashi M, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, et al. Phosphorylated AKT expression is associated with PIK3CA mutation, low stage and favorable outcome in 717 colorectal cancers. Cancer. 2011;117:1399–1408. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kure S, Nosho K, Baba Y, Irahara N, Shima K, Ng K, et al. Vitamin D receptor expression is associated with PIK3CA and KRAS mutations in colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2765–2772. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Velho S, Oliveira C, Ferreira A, Ferreira AC, Suriano G, Schwartz S, Jr., et al. The prevalence of PIK3CA mutations in gastric and colon cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1649–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jehan Z, Bavi P, Sultana M, Abubaker J, Bu R, Hussain A, et al. Frequent PIK3CA gene amplification and its clinical significance in colorectal cancer. J Pathol. 2009;219:337–346. doi: 10.1002/path.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sartore-Bianchi A, Martini M, Molinari F, Veronese S, Nichelatti M, Artale S, et al. PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancer are associated with clinical resistance to EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1851–1857. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Prenen H, De Schutter J, Jacobs B, De Roock W, Biesmans B, Claes B, et al. PIK3CA mutations are not a major determinant of resistance to the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3184–3188. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jhawer M, Goel S, Wilson AJ, Montagna C, Ling YH, Byun DS, et al. PIK3CA mutation/PTEN expression status predicts response of colon cancer cells to the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1953–1961. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhao L, Vogt PK. Helical domain and kinase domain mutations in p110alpha of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase induce gain of function by different mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2652–2657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712169105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, et al. Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation status, and colorectal cancer survival. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1596–1606. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kaur J, Sanyal SN. PI3-kinase/Wnt association mediates COX-2/PGE(2) pathway to inhibit apoptosis in early stages of colon carcinogenesis: chemoprevention by diclofenac. Tumour Biol. 2010;31:623–631. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Uddin S, Ahmed M, Hussain A, Assad L, Al-Dayel F, Bavi P, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition inhibits PI3K/AKT kinase activity in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:382–394. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pasche B. Aspirin - from prevention to targeted therapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1650–1651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1210322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Neugut AI. Aspirin as adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer: a promising new twist for an old drug. JAMA. 2009;302:688–689. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Straussman R, Morikawa T, Shee K, Barzily-Rokni M, Qian ZR, Du J, et al. Tumor microenvironment contributes to innate RAF-inhibitor resistance through HGF secretion. Nature. 2012;487:500–504. doi: 10.1038/nature11183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Langley RE, Rothwell PM. Biological markers: Potential biomarker for aspirin use in colorectal cancer therapy. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2013;10:8–10. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ghosh S, Matsuoka Y, Asai Y, Hsin KY, Kitano H. Software for systems biology: from tools to integrated platforms. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:821–832. doi: 10.1038/nrg3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ogino S, Lochhead P, Chan AT, Nishihara R, Cho E, Wolpin BM, et al. Molecular pathological epidemiology of epigenetics: Emerging integrative science to analyze environment, host, and disease. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:465–484. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ogino S, Stampfer M. Lifestyle factors and microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer: The evolving field of molecular pathological epidemiology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:365–367. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ogino S, Chan AT, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci E. Molecular pathological epidemiology of colorectal neoplasia: an emerging transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary field. Gut. 2011;60:397–411. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.217182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Boyle T, Fritschi L, Heyworth J, Bull F. Long-term sedentary work and the risk of subsite-specific colorectal cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1183–1191. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Curtin K, Slattery ML, Samowitz WS. CpG island methylation in colorectal cancer: past, present and future. Pathology Research International. 2011;2011:902674. doi: 10.4061/2011/902674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hughes LA, Simons CC, van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, de Goeij AF, de Bruine AP, et al. Body size, physical activity and risk of colorectal cancer with or without the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP). PLoS One. 2011;6:e18571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kelley RK, Wang G, Venook AP. Biomarker use in colorectal cancer therapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9:1293–1302. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2011.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hughes LA, Khalid-de Bakker CA, Smits KM, van den Brandt PA, Jonkers D, Ahuja N, et al. The CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer: Progress and problems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1825:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Limburg PJ, Limsui D, Vierkant RA, Tillmans L, Wang AH, Lynch CF, et al. Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Relation to Somatic KRAS Mutation Status among Older Women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:681–684. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hughes LA, Williamson EJ, van Engeland M, Jenkins MA, Giles G, Hopper J, et al. Body size and risk for colorectal cancers showing BRAF mutation or microsatellite instability: a pooled analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1060–1072. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ku CS, Cooper DN, Wu M, Roukos DH, Pawitan Y, Soong R, et al. Gene discovery in familial cancer syndromes by exome sequencing: prospects for the elucidation of familial colorectal cancer type X. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1055–1068. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, Batts KP, Burke CA, Burt RW, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1315–1329. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Koshiol J, Lin SW. Can Tissue-Based Immune Markers be Used for Studying the Natural History of Cancer? Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22:520–530. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gay LJ, Mitrou PN, Keen J, Bowman R, Naguib A, Cooke J, et al. Dietary, lifestyle and clinico-pathological factors associated with APC mutations and promoter methylation in colorectal cancers from the EPIC-Norfolk Study. J Pathol. 2012;228:405–415. doi: 10.1002/path.4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dogan S, Shen R, Ang DC, Johnson ML, D'Angelo SP, Paik PK, et al. Molecular Epidemiology of EGFR and KRAS Mutations in 3026 Lung Adenocarcinomas: Higher Susceptibility of Women to Smoking-related KRAS-mutant Cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6169–6177. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kuller LH. Invited Commentary: The 21st century epidemiologist -- a need for different training? Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:668–671. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Greystoke A, Mullamitha SA. How many diseases is colorectal cancer? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:564741. doi: 10.1155/2012/564741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Spitz MR, Caporaso NE, Sellers TA. Integrative cancer epidemiology--the next generation. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:1087–1090. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rosty C, Young JP, Walsh MD, Clendenning M, Walters RJ, Pearson S, et al. Colorectal carcinomas with KRAS mutation are associated with distinctive morphological and molecular features. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:825–834. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Campbell PT, Patel AV, Newton CC, Jacobs EJ, Gapstur SM. Associations of Recreational Physical Activity and Leisure Time Spent Sitting With Colorectal Cancer Survival. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:876–885. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Weijenberg MP, Hughes LA, Bours MJ, Simons CC, van Engeland M, van den Brandt PA. The mTOR Pathway and the Role of Energy Balance Throughout Life in Colorectal Cancer Etiology and Prognosis: Unravelling Mechanisms Through a Multidimensional Molecular Epidemiologic Approach. Current nutrition reports. 2013;2:19–26. doi: 10.1007/s13668-012-0038-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Buchanan DD, Win AK, Walsh MD, Walters RJ, Clendenning M, Nagler BN, et al. Family History of Colorectal Cancer in BRAF p.V600E mutated Colorectal Cancer Cases. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:917–926. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Burnett-Hartman AN, Passarelli MN, Adams SV, Upton MP, Zhu LC, Potter JD, et al. Differences in epidemiologic risk factors for colorectal adenomas and serrated polyps by lesion severity and anatomical site. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:625–637. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lam TK, Spitz M, Schully SD, Khoury MJ. “Drivers” of Translational Cancer Epidemiology in the 21st Century: Needs and Opportunities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:181–188. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Burnett-Hartman AN, Newcomb PA, Potter JD, Passarelli MN, Phipps AI, Wurscher MA, et al. Genomic aberrations occuring in subsets of serrated colorectal lesions but not conventional adenomas. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2863–2872. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ogino S, Beck AH, King EE, Sherman ME, Milner DA, Giovannucci E. Ogino et al. respond to “The 21st century epidemiologist”. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:672–674. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Begg CB. A strategy for distinguishing optimal cancer subtypes. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:931–937. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Begg CB, Zabor EC. Detecting and Exploiting Etiologic Heterogeneity in Epidemiologic Studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:512–518. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ogino S, Nosho K, Meyerhardt JA, Kirkner GJ, Chan AT, Kawasaki T, et al. Cohort study of fatty acid synthase expression and patient survival in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5713–5720. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, Meyerhardt JA, Shima K, Nosho K, et al. Association of CTNNB1 (beta-catenin) alterations, body mass index, and physical activity with survival in patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2011;305:1685–1694. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Phipps AI, Shi Q, Newcomb PA, Nelson GD, Sargent DJ, Alberts SR, et al. Associations Between Cigarette Smoking Status and Colon Cancer Prognosis Among Participants in North Central Cancer Treatment Group Phase III Trial N0147. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2016–2023. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Vrieling A, Kampman E. The role of body mass index, physical activity, and diet in colorectal cancer recurrence and survival: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:471–490. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Siddiqi SM, McTiernan A, Alfano CM. Physical Activity, Biomarkers, and Disease Outcomes in Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:815–840. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Waldron L, Ogino S, Hoshida Y, Shima K, McCart Reed AE, Simpson PT, et al. Expression profiling of archival tissues for long-term health studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6136–6146. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. The Nurses’ Health Study: lifestyle and health among women. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:388–396. doi: 10.1038/nrc1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Colditz GA. Ensuring long-term sustainability of existing cohorts remains the highest priority to inform cancer prevention and control. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:649–656. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9498-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Shanmuganathan R, Nazeema Banu B, Amirthalingam L, Muthukumar H, Kaliaperumal R, Shanmugam K. Conventional and Nanotechniques for DNA Methylation Profiling. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Damania D, Roy HK, Subramanian H, Weinberg DS, Rex DK, Goldberg MJ, et al. Nanocytology of rectal colonocytes to assess risk of colon cancer based on field cancerization. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2720–2727. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Dahlin AM, Palmqvist R, Henriksson ML, Jacobsson M, Eklof V, Rutegard J, et al. The Role of the CpG Island Methylator Phenotype in Colorectal Cancer Prognosis Depends on Microsatellite Instability Screening Status. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1845–1855. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Bae JM, Kim JH, Kang GH. Epigenetic alterations in colorectal cancer: the CpG island methylator phenotype. Histology and histopathology. 2013;28:585–595. doi: 10.14670/HH-28.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Nosho K, Irahara N, Shima K, Kure S, Kirkner GJ, Schernhammer ES, et al. Comprehensive biostatistical analysis of CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer using a large population-based sample. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Teodoridis JM, Hardie C, Brown R. CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in cancer: Causes and implications. Cancer Lett. 2008;268:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Zlobec I, Bihl MP, Schwarb H, Terracciano L, Lugli A. Clinicopathological and protein characterization of BRAF- and K-RAS-mutated colorectal cancer and implications for prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:367–380. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Sanchez JA, Krumroy L, Plummer S, Aung P, Merkulova A, Skacel M, et al. Genetic and epigenetic classifications define clinical phenotypes and determine patient outcomes in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1196–1204. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Zlobec I, Bihl M, Foerster A, Rufle A, Lugli A. Comprehensive analysis of CpG Island Methylator Phenotype (CIMP)-high, -low, and -negative colorectal cancers based on protein marker expression and molecular features. J Pathol. 2011;225:336–343. doi: 10.1002/path.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Phipps AI, Buchanan DD, Makar KW, Burnett-Hartman AN, Coghill AE, Passarelli MN, et al. BRAF mutation status and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis according to patient and tumor characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1792–1798. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Yamamoto E, Suzuki H, Yamano HO, Maruyama R, Nojima M, Kamimae S, et al. Molecular Dissection of Premalignant Colorectal Lesions Reveals Early Onset of the CpG Island Methylator Phenotype. The American journal of pathology. 2012;181:1847–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Phipps AI, Buchanan DD, Makar KW, Win AK, Baron JA, Lindor NM, et al. KRAS-mutation status in relation to colorectal cancer survival: the joint impact of correlated tumour markers. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1757–1764. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Monzon FA, Ogino S, Hammond EH, Halling KC, Bloom KJ, Nikiforova MN. The Role of KRAS Mutation Testing in the Management of Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1600–1606. doi: 10.5858/133.10.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Funkhouser WK, Lubin IM, Monzon FA, Zehnbauer BA, Evans JP, Ogino S, et al. Relevance, pathogenesis, and testing algorithm for mismatch repair-defective colorectal carcinomas: A report of the Association for Molecular Pathology. J Mol Diagn. 2012;14:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Barry ER, Morikawa T, Butler BL, Shrestha K, de la Rosa R, Yan KS, et al. Restriction of intestinal stem cell expansion and the regenerative response by YAP. Nature. 2013;493:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Ogino S, King EE, Beck AH, Sherman ME, Milner DA, Giovannucci E. Interdisciplinary education to integrate pathology and epidemiology: towards molecular and population-level health science. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:659–667. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Khoury MJ, Lam TK, Ioannidis JP, Hartge P, Spitz MR, Buring JE, et al. Transforming epidemiology for 21st century medicine and public health. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:508–516. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Wuchty S, Jones BF, Uzzi B. The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science. 2007;316:1036–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.1136099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Sharp PA, Langer R. Research agenda. Promoting convergence in biomedical science. Science. 2011;333:527. doi: 10.1126/science.1205008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Eklof V, Wikberg ML, Edin S, Dahlin AM, Jonsson BA, Oberg A, et al. The prognostic role of KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and PTEN in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2153–2163. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Voutsina A, Tzardi M, Kalikaki A, Zafeiriou Z, Papadimitraki E, Papadakis M, et al. Combined analysis of KRAS and PIK3CA mutations, MET and PTEN expression in primary tumors and corresponding metastases in colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:302–313. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Phipps AI, Makar KW, Newcomb PA. Descriptive profile of PIK3CA-mutated colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. International journal of colorectal disease. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1715-8. published online (doi. 10.1007/s00384-00013-01715-00388) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Day FL, Jorissen RN, Lipton L, Mouradov D, Sakthianandeswaren A, Christie M, et al. PIK3CA and PTEN gene and exon mutation-specific clinicopathological and molecular associations in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3614. published online (doi. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1112-3614) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Deming DA, Leystra AA, Nettekoven L, Sievers C, Miller D, Middlebrooks M, et al. PIK3CA and APC mutations are synergistic in the development of intestinal cancers. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.167. published online (doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.1167) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]