Abstract

Background

Childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are more insulin resistant (IR) and have higher levels of several cardiovascular (CV) risk factors even while still children. This study examines specific treatment exposures associated with CV risk factors and IR.

Methods

CCS age 9–18 years at study entry and in remission ≥5 years from diagnosis (n=319) and 208 sibling controls were recruited into this cross-sectional study that included physiologic assessment of IR (hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp) and assessment of CV risk factors.. Regression and recursive tree modeling were used to ascertain treatment combinations associated with IR and CV risk.

Results

Mean current age of CCS was 14.5yr, 54% were male (siblings 13.6yr, 54% male). Diagnoses included leukemia (35%), brain tumors (36%), solid tumors (33%) or lymphoma (6%). Among CCS, analysis of individual chemotherapy agents failed to find associations with CV risk factors or IR. Compared to siblings, IR was significantly higher in CCS who received platinum plus cranial radiation (CRT, 92% brain tumors) and in those who received steroids but no platinum (majority leukemia). IR did not differ between CCS who received surgery alone vs. siblings. Within survivor comparisons failed to elucidate treatment combinations that increased IR compared to those who received surgery only.

Conclusions

Exposure to platinum, CRT or steroids is associated with IR and CV risk factors and should be taken into consideration in the development of screening recommendations for CV risk.

Impact

Earlier identification of CCS who may benefit from targeted prevention efforts may reduce their future risk of CV disease.

Keywords: cancer survivor, cardiovascular risk, insulin resistance, late effects

INTRODUCTION

Improvements in treatment of childhood cancer over the past 3 decades have led to an overall survival rate of 80%. Currently, 1 in 900 children under the age of 14 are cancer survivors. Large cohort studies in multiple populations have found that cardiovascular-related deaths occur with at least 7 times the expected rate in the general population, and may account for a quarter of all excess deaths by 45 years after diagnosis.CV.(1–3) While congestive heart failure from anthracycline exposure accounts for many of these deaths, equal numbers are related to cardiovascular disease such as myocardial infarction, stoke, and other vascular diseases.(2, 4) Some studies suggest that the etiology of these cardiovascular events is associated with the development of insulin resistance, as is frequently the case with cardiovascular disease in the general population, and that exposure to chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy in CCS is associated with the development of IR and other cardiovascular risk factors such as lipid abnormalities, adiposity, and hypertension.(5–10) We have previously reported that when compared to a sibling control group, CCS who were a minimum of 5 years from diagnosis, but who were still younger than age 18, had greater adiposity (higher waist circumference, percent body fat and lower lean body mass), and higher levels of several cardiovascular risk factors including total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides.(11) In addition, these survivors were found to be significantly more insulin resistant as measured by euglycemic insulin clamp studies than control subjects even after adjusting for adiposity. However, that analysis did not examine the effect of individual therapeutic exposures on the development of cardiovascular risk factors or insulin resistance. To address that gap in knowledge, we hypothesized that the presence of abnormal cardiovascular risk factors and/or insulin resistance would be more likely to occur as a result of exposure to certain chemotherapy agents and/or radiation therapy whereas others would have little impact on this risk. Identification of treatments associated with cardiovascular risk would be useful for development of long term screening recommendations for patients potentially at risk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Human Subjects Committee at the University of Minnesota and Children’s Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota. Consent (and assent as appropriate) was obtained from children and their guardian(s). The participants were CCS, age 9–18 years at examination, in remission at least five years from cancer diagnosis and who had received treatment at one of these institutions. Recipients of hematopoietic cell transplant were excluded. Of 723 eligible CCS, 66 could not be located. The remaining 657 were contacted, and consent for participation was obtained from 322 (49%). Three CCS were determined to be ineligible after consent, leaving the final study population of 319 CCS (see supplementary Figure 1 for consort diagram). There were no significant differences in age, sex, race, diagnosis, age at diagnosis and length of follow-up (time from diagnosis to study evaluation) between the CCS participants and the CCS non-participants.(11) A convenience control group was assembled by asking, each CCS participant to identify any healthy siblings who were 9–18 years old and had never had cancer. The siblings were informed of the study by their parents and if they agreed to participate they were evaluated at the same time as the CCS. From the 322 families enrolled (including the 3 later determined to be ineligible), 164 had no eligible or consenting siblings , 124 had one sibling that participated, 33 had more than one sibling participate (n=72). Twelve additional siblings from an identical companion study being performed simultaneously in a hematopoietic cell transplant population of survivors who met the same eligibility criteria were also included in the final control group (n=208) for analysis.

Subject and Control Assessments

Participants underwent a two-day examination, the details of which have been published previously(11), but in brief, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measurements were obtained for body composition, including percent fat mass (PFM) and total lean body mass (TLM, in kilograms). The average of two blood pressure measurements from the right arm of rested, seated subjects was used. Hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamps were conducted after a 10–12 hour overnight fast(12). Insulin sensitivity, adjusted for lean body mass (M-lbm) was determined by the amount of glucose required to maintain euglycemia over the final 40 minutes of the clamp study and expressed as mg/kg/min of glucose. Lower M-lbm values are indicative of lower insulin sensitivity, i.e., greater insulin resistance. Fasting blood samples for glucose, insulin and lipids were obtained, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was calculated by the Friedewald equation.

Therapeutic Exposures

Therapeutic exposures were abstracted from medical records using a standardized form which captured all chemotherapy exposures in a yes/no format and cumulative dose exposures for selected agents. Radiation therapy exposures were collected (site, total dose administered). Only drugs to which at least 5 patients were exposed were included in the analysis, and these were then categorized into drug classes based on known mechanisms of action to form the following categories for analysis [cumulative doses available for drugs indicted with an (*)]: alkylating agents (lomustine, procarbazine, thiotepa, ifosfamide*, cyclophosphamide*); anthracyclines (daunorubicin*, doxorubicin*, idarubicin*); intrathecal (IT) or non-IT antimetabolites (cytosine arabinoside, mecaptopurine, methotrexate*, thioguanine); enzymes (erwinia, L-, and PEG-asparaginase); platinum agents (carboplatinum*, cisplatinum*); plant alkyloids (vincristine, vinblastine); steroids (prednisone*, dexamethasone*); and topoisomerase inhibitors (etoposide*). Cumulative doses of anthracyclines were converted to the equivalent doxorubicin doses by the following formulas: daunorubicin*0.83 and idarubicin*5. Total platinum doses are expressed as cisplatinum equivalents using carboplatinum divided by 4. Prednisone equivalent doses utilized the conversion of 1 mg prednisone = 0.15mg dexamethasone.

Statistical Methods

Linear regression modeling of the effects of individual chemotherapy agents and radiotherapy

Among CCS subjects, models were used to estimate the independent effects of each chemotherapy agent (both yes/no and by dose categories based on median or tertile value cutoffs) on each outcome. The effect of radiation was evaluated by comparing cranial radiotherapy (CRT; whole brain + partial brain) with no CRT (abdominal radiation, other radiation, no radiation combined). Outcomes of interest in this analysis were M-lbm, insulin*, blood glucose*, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP)*, HDL-cholesterol*, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides*, and the selected body-composition measures (waist circumference*, TLM, PFM and body mass index (BMI). Outcomes with an asterisk were included in the analysis of having multiple adverse metabolic conditions.(13, 14) All models were adjusted by age-at-study, race, sex, and Tanner score. For outcomes aside from body-composition measures, models were further adjusted by PFM and separately by BMI. These models were then further adjusted by CRT to account for possible independent effects of cranial radiation.

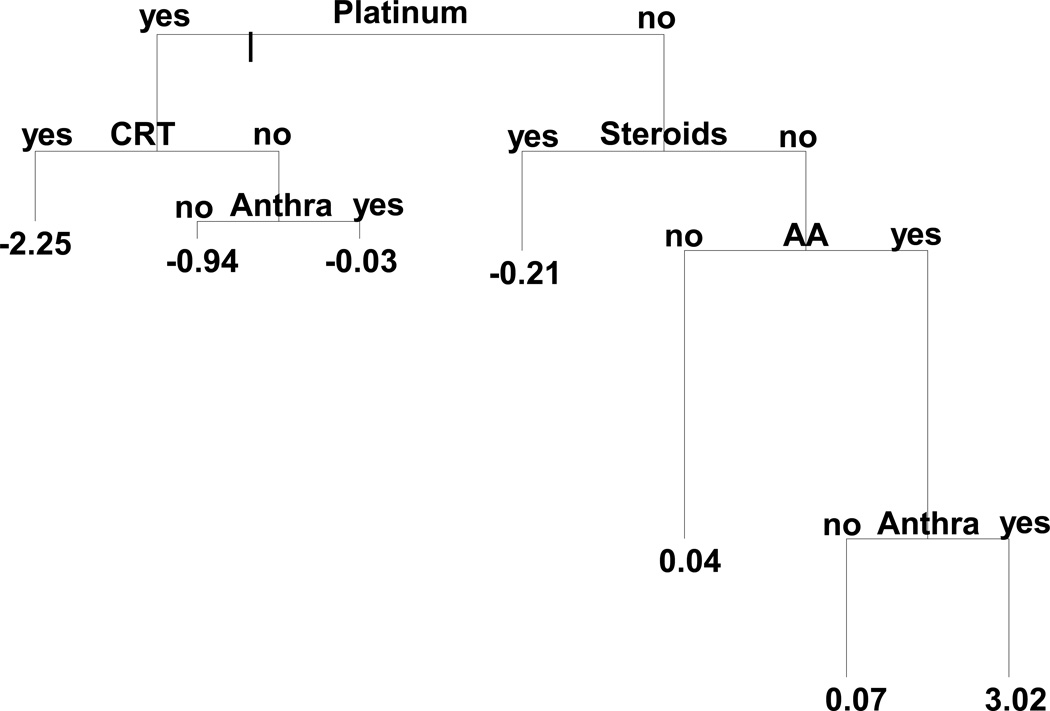

Classification and Regression Tree Modeling and Treatment Combinations

In an alternative approach, we used regression tree modeling to first determine optimal treatment combinations to use as risk factors in subsequent multivariable regression modeling.(15) This approach selects from an initial input list of predictors, selecting a binary categorization that maximizes the difference in outcomes. The data are split according to these two categories and this selection process is repeated for subsequent predictors, called recursive partitioning, until a pre-specified stopping criterion is met. The result is a set of cohort partitions that could be translated into treatment combination variables. M-lbm, adjusted for age-at-study, sex, race, and Tanner Score, was used as the primary outcome for tree modeling given our hypothesis that changes in insulin resistance are etiologic for subsequent cardiovascular disease. To implement this in the context of adjusted models, residuals from a linear regression model of M-lbm with the same covariates were used as the outcome in the tree modeling. Binary therapeutic exposures selected as candidate predictors in the tree modeling analysis included CRT, alkylating agents, anthracyclines, plant alkyloids, platinum agents, and steroids (Figure 1). The resulting regression tree was then simplified, aided by the Bayes Information Criterion to obtain a more parsimonious tree. Numbers shown on the terminating nodes of the tree represent the predicted values of the response from the model. The length of each branch is representative of the importance of their parent split. Each branch of the final tree then represents a set of rules that were directly translated into mutually-exclusive treatment combinations (Figure 1, Table 3 and Supplementary Table S1) specifying both exposure and non-exposure. These mutually exclusive treatment combinations were then used as categorical predictors in new linear regression models to directly estimate their combined effects on various outcomes first between CCS and siblings to illustrate the magnitude of differences between specifically treated subjects and a completely untreated population, and secondly, within CCS to evaluate differences between subsets of cancer survivors, with all analyses adjusted for age-at-study, race, sex, and Tanner Score. Outcomes were selected to proceed to multivariable linear regression modeling with these treatment combinations if there was a statistically significant association between the outcome and at least one of the treatments tested independently. Selected outcome variables were M-lbm, TLM, PFM, BMI, and LDL-cholesterol. Finally, logistic regression models were fit to evaluate the associations between the same treatment combinations with the binary outcome defined as having 2 or more metabolic syndrome conditions. All analyses involving both CCS and siblings accounted for intra-family correlation using robust variance estimates and generalized estimating equations. Analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 and Tibco Spotfire S+ 8.2 (regression tree modeling) for Windows.

Figure 1.

Regression tree for M-lbm, pruned by Bayes Informational Criterion and collapsed using regression modeling (see Methods for details). Numbers at the terminal notes represent predicted values of age, sex and race adjusted M-lbm. The length of each branch is proportional to the reduction in deviance due to that split. AA=Alkylating Agents, Anthra = Anthracycline, CRT = Cranial Radiation.

Table 3.

Number and percent of primary cancer diagnoses in each treatment combination

| Primary Cancer Diagnosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukemia (N=110) |

Solid Tumor (N=127) |

CNS (N=82) |

|

| Treatment Combinations | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Platinum + CRT | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) | 11 (91.7) |

| Platinum + anthracycline; no CRT | 0 (0) | 16 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Platinum; no CRT or anthracycline | 0 (0) | 3 (18.7) | 13 (81.3) |

| Steroids; no platinum | 109 (77.9) | 24 (17.1) | 7 (5) |

| No platinum, steroid, or alkylating agent | 1 (2.3) | 30 (68.2) | 13 (29.5) |

| Alkylating agents; no platinum, steroid, or anthracycline | 0 (0) | 6 (75) | 2 (25) |

| Alkylating agent + anthracycline; no platinum or steroid | 0 (0) | 23 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Surgery Only | 0 (0) | 24 (40) | 36 (60) |

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Characteristics of the study population at the time of the study are shown in Table 1. The mean age of survivors was 14.5 yrs, 54% were male, and the majority white/non-Hispanic race. Survivors were slightly older and more likely to be white/non-Hispanic compared to sibling controls. CCS diagnostic groups included acute leukemias (35%), tumors of the central nervous system (CNS, 36%) and other solid tumors (33%) or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (6%). Survivors in all diagnostic categories were on average approximately 10 years post-diagnosis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Population

| Variable | Category | CCS (n=319) | Siblings (n=208) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Years (mean ± SE a) | 14.5 ± 0.1 | 13.6 ± 0.2 |

| Sex b | Male | 171 (54%) | 112 (54%) |

| Female | 148 (46%) | 96 (46%) | |

| Race/Ethnicityb, c | White Non-Hispanic | 274 (86%) | 194 (93%) |

| Others | 45 (14%) | 14 (7%) | |

| White Hispanic | 4 (1%) | 4 (2%) | |

| Black | 14 (4%) | 3 (1%) | |

| Others | 27 (9%) | 7 (4%) | |

| Tanner | Tanner Stage (mean ± SE a) | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 |

| 1b | 33 (10%) | 33 (17%) | |

| 2 | 54 (17%) | 32 (15%) | |

| 3 | 39 (12%) | 36 (17%) | |

| 4 | 88 (28%) | 45 (22%) | |

| 5 | 105 (33%) | 60 (29%) | |

| Diagnosis b | Leukemia | NA | |

| Acute Lymphoblastic | 102 (32%) | ||

| Acute Myeloid | 8 (3%) | ||

| CNS | NA | ||

| Glial tumors | 38 (12%) | ||

| Retinoblastoma | 16 (5%) | ||

| Other CNS tumors | 15 (5%) | ||

| Neuroectodermal tumors | 13 (4%) | ||

| Solid Tumors | NA | ||

| Sarcoma | 32 (10%) | ||

| Renal | 30 (9%) | ||

| Neuroblastoma | 23 (7%) | ||

| Other solid tumors | 22 (7%) | ||

| Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | 20 (6%) | ||

| Time from diagnosis to study | Years (mean ± SE a) (range) | ||

| All CCS | 10.1 ± 0.2 (5.0–17.8) | NA | |

| Leukemia | 10.2 ± 0.3 (5.1–16.0) | ||

| CNS | 9.7 ± 0.4 (4.3–17.1) | ||

| Solid Tumors | 10.2 ± 0.3 (5.5– 17.8) |

SE: Standard Error;

Data displayed as n (%), Other solid tumors include: breast cancer (n=2), Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (n=4), germ cell tumor (n=11), hepatoblastoma (n=4), melanoma (n=1);

Per low cell counts, White Hispanic, Black, and Other categories collapsed for the comparison between CCS and controls..

Linear Regression Results of Individual Exposures

For each therapeutic category (Table 2) we examined the mean values for M-lbm, insulin, blood glucose, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, BMI, waist circumference, TLM, and PFM, comparing those exposed to an individual category with all subjects who did not have that specific exposure. Overall this analysis failed to elucidate individual chemotherapy categories that were associated with clinically significant changes in any of our outcomes (data not shown). A similar analysis was then performed examining the effect of different cumulative dose categories (Supplementary Table S2), which also failed to produce any informative results. However, when comparing individual therapeutic exposures in survivors to the sibling control group, all chemotherapy agents with the exception of platinum and topoisomerase inhibitors were associated with a statistically significant decrease in TLM, and an increase in PFM and a lower M-lbm indicating greater insulin resistance. Platinum exposure was similarly associated with lower TLM and lower M-lbm, but with this agent PFM was not increased, although, triglyceride levels were higher. The only class of agents which had no significant impact on any of the cardiovascular outcomes in survivors compared to controls was topoisomerase inhibitors (data not shown).

Table 2.

Therapeutic Exposures by drug category and cranial radiation.

| Therapeutic Exposure | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Cranial Radiation* | 43 | 13.5 |

| Alkylating Agents | 184 | 57.7 |

| Anthracyclines | 183 | 57.4 |

| Antimetabolites, Non-IT Administration Route | 136 | 42.6 |

| Antimetabolites, IT Administration Route | 131 | 41.1 |

| Enzymes | 110 | 34.5 |

| Platinum | 44 | 13.8 |

| Plant Alkyloids | 209 | 65.5 |

| Steroids | 141 | 44.2 |

| Topoisomerase Inhibitors | 70 | 21.9 |

whole brain without spine (n=12), whole brain + spine (n=14), partial brain (n=17, including any CNS directed radiation that was not whole brain)

Seventy-seven patients received some form of radiotherapy with the primary site of radiation defined as: whole or partial abdomen (n=19), whole brain without spine (n=12), whole brain with spine (n=14), partial brain (n=17), and other (n=15, including lung, chest wall, abdomen, extremity, mediastinal and other miscellaneous sites). Thirty-eight patients received radiation to more than one site but were categorized as above based on primary site of radiation. In standard linear regression modeling, TLM was reduced among those who received any whole brain radiation either with spine radiation (31.0 kg vs. 40.6 kg, p<0.001), or without (35.7 kg vs. 40.6 kg, p=0.023) or “other” radiation (34.9 vs. 40.6, p=0.003), as compared with none. There was no significant effect on PFM.

Tree Modeling and Treatment Combination Variables: survivors compared to siblings

Using tree-based methodology as described above, a set of optimal rules for defining treatment combinations that could distinguish different levels of M-lbm were derived (Figure 1). Table 3 provides a breakdown of the frequency of each of these combinations within each underlying diagnosis group. Supplementary Table S1 shows the details of the additional treatment exposures utilized in the tree model within each treatment category besides the ones that were included in the modeling partitions.

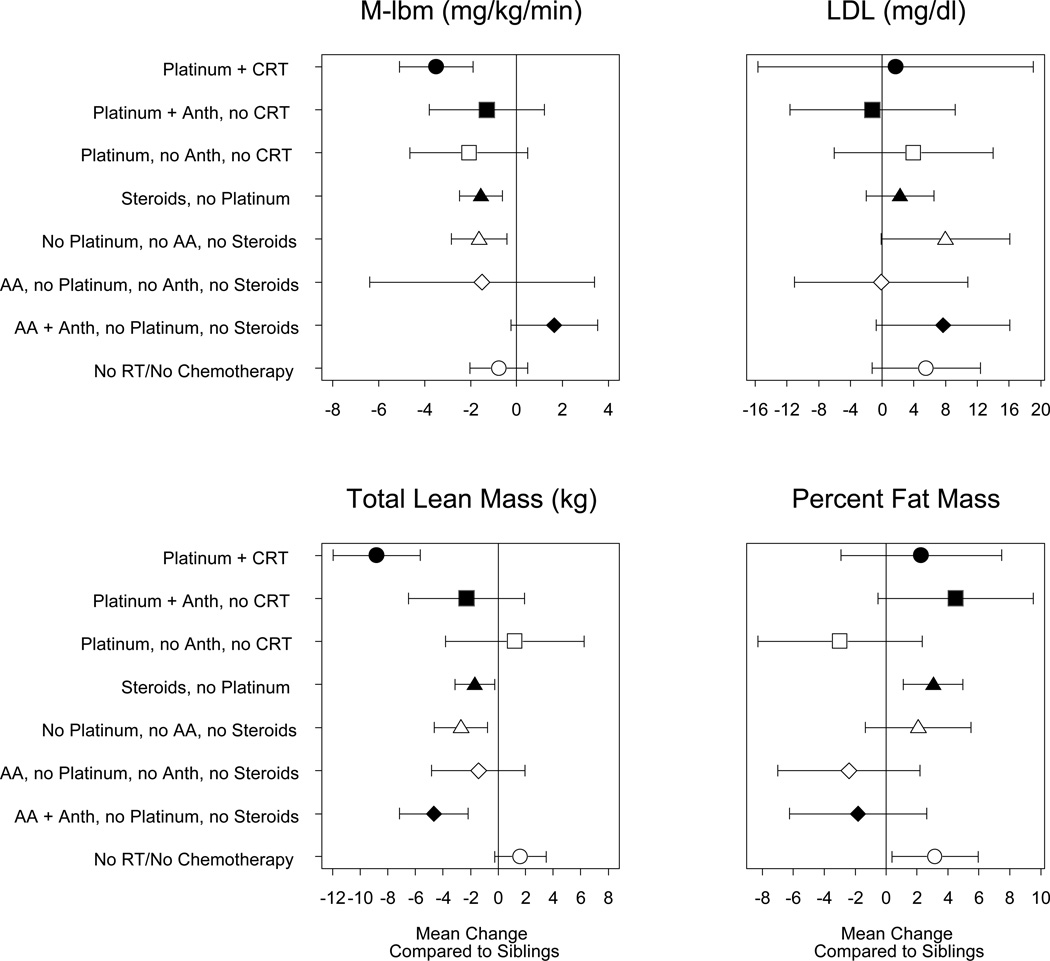

Figure 2 displays the parameter estimates (mean change) from linear regression models comparing each of the treatment combinations to siblings. Several treatment categories were found to be associated with increased insulin resistance (lower M--lbm) among survivors compared to siblings. Those who received platinum agents plus CRT (92% CNS tumor survivors) were most insulin resistant, with an M-lbm that was 26% (3.5 mg/kg/min) lower than siblings (p<0.001). Compared with siblings, survivors who received steroids but no platinum agents (78% leukemia), and those who did not receive any platinum, steroids, or alkylating agents (68% solid tumors; 30% CNS tumors) also had lower M-lbm (−1.5 to −1.6 mg/kg/min; p<0.01).

Figure 2.

Plot of effect size and 95% confidence intervals of treatment combinations on outcomes M-lbm, LDL (adjusted for percent fat mass), total lean mass, and percent fat mass, compared to siblings.( Anth, anthracyclines; AA alkylating agents; RT, any radiation therapy, CRT cranial radiation

LDL, adjusted for PFM, was 8 mg/dl higher among survivors who were in the group whose treatment exposures did not include platinum, steroids, or alkylating agents compared to siblings (p=0.05). No other survivor group was found to be significantly different from sibling controls. TLM was significantly lower among several treatment groups compared with siblings. The most significant difference was with survivors treated with both platinum and CRT, who had TLM 8.8 kg lower (p<0.001) than siblings. PFM was 3% higher in survivors who were treated with steroids but no platinum agents (p=0.002) and also those treated with surgery alone (63% CNS tumors; p=0.03) compared to siblings (Figure 3). No other groups had statistically significant differences in PFM compared with siblings.

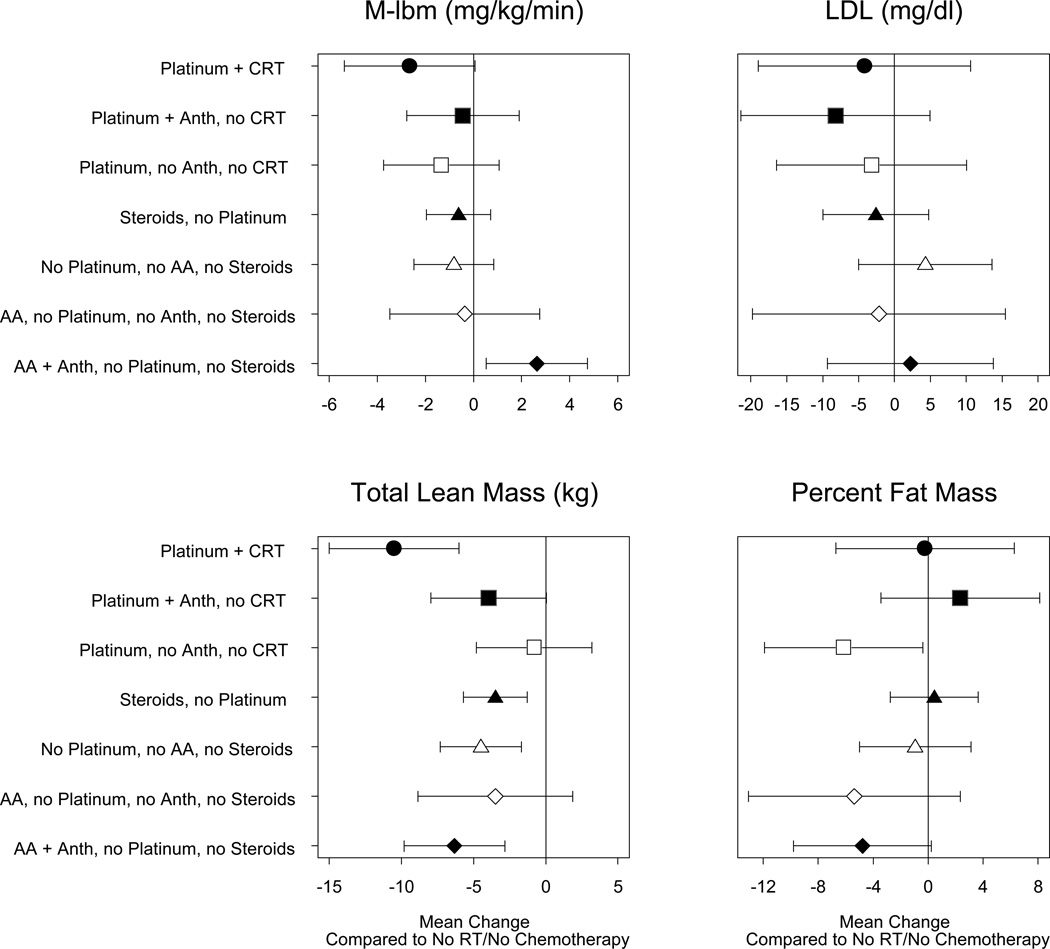

Figure 3.

Plot of effect size and 95% confidence intervals of treatment combinations for all survivors (no siblings) on outcomes M-lbm, LDL (adjusted for percent fat mass), total lean mass, and percent fat mass, as compared to surgery only survivors. ( Anth, anthracyclines; AA alkylating agents; RT, any radiation therapy, CRT cranial radiation

Tree Modeling and Treatment Combination Variables: within survivor comparisons

In contrast to comparison with sibling controls, overall, when compared to survivors treated with surgery alone (63% CNS tumor patients), the risk of being insulin resistant did not differ significantly among the different treatment groups, with the exception of survivors who received alkylating agents plus anthracyclines, but no platinum or steroids (100% solid tumors) being less insulin resistant (M-lbm 2.6mg/kg/min higher, p=0.01; Figure 3). No treatment category was found to be associated with a risk of elevated LDL. Several treatment combinations were associated with a significant negative effect on TLM compared to those who treated with surgery alone. Survivors treated with platinum plus CRT were most affected, with an adjusted TLM that was 10.5 kg lower (p<0.01). Regarding PFM, only survivors treated with platinum without CRT or anthracyclines (81% CNS tumors) were significantly different from those treated with surgery alone (6.2% lower, p=0.04). Amongst all survivor groups, the surgery only category had the highest mean BMI, significantly higher than multiple other groups, including survivors treated with platinum and CRT (p=0.02; data not shown).

Risk for Multiple Conditions

Logistic regression was used to evaluate associations between these treatment categories and the likelihood of having two or more adverse metabolic conditions (blood glucose, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, waist circumference). Survivors who received platinum but no CRT or anthracyclines (81% CNS tumors) were at greatest risk (OR 4.3, 95% CI 1.4–13) compared with siblings. Other survivor groups at increased risk compared to siblings included those treated with steroid but no platinum agents (78% leukemia; OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1–3.1) and those treated with surgery alone (60% CNS tumors; OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.0–4.3). While the platinum plus CRT group was associated with increased insulin resistance, this group was not found to be more likely to have two or more of the other specific metabolic conditions.

DISCUSSION

Advances made in treatment of childhood cancers have been attributed to the utilization of multi-agent/multimodal therapy incorporating treatment protocols that consist of several agents given sequentially or in alternating cycles, with or without radiation therapy. Although some aspects of therapy have changed over the past 30 years, particularly decreased use of radiotherapy for select diagnoses, many agents and treatment combinations used historically, including those featured in our study, remain integral parts of contemporary pediatric therapy.(16, 17) The acute toxicities of most of these therapies are well described. However, the majority of these drugs are not utilized as single agents and thus when examining the impact of specific chemotherapy drugs or radiation on long term toxicities, it is difficult to separate out the effect of individual therapeutic exposures regardless of the particular late effect that is being examined. This remains an issue even in studies such as ours in which the overall sample size was relatively large, but various disease based subgroups were smaller and the treatments utilized heterogeneous. Despite this challenge, the primary aim of this study was to examine the impact of treatment exposures on the risk for developing insulin resistance, changes in body composition and cardiovascular risk factors in order to further delineate which exposure(s) impart the most risk in order to inform risk based screening and prevention strategies.

Among survivors we were not able to detect an exposure to an individual chemotherapeutic agent that was clearly associated with a higher risk of insulin resistance, even after examining dose categories. However, compared to siblings, nearly all chemotherapeutic agents when examined individually, appeared to be associated with lower TLM, greater PFM and insulin resistance. Thus, treatment does appear to contribute to long-term physiologic changes which may predispose to cardiovascular disease in survivors of childhood cancer.

Given that in the current therapeutic era, no patient receives a single agent in isolation we, have attempted in this analysis to examine the impact of different treatment combinations on insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk factors. Based on the fact that we intended this analysis to be driven by treatment exposures rather than cancer diagnosis, we utilized regression tree modeling methodology to form exposure groups that were determined by the strength of the association between the agents in a model with insulin resistance as the primary outcome of interest. Although some combinations did appear to consist primarily of one diagnostic group versus others, other combinations identified by the tree classification approach featured a mixture of diagnoses.

Examining the categories of treatments included in the tree model (CRT, alkylating agents, anthracycline exposure, plant alkyloids, platinum agents, and steroids), it can be seen anthracyclines, platinum, CRT and steroids were the exposures most strongly associated with insulin resistance and the ones that primarily drove the segregation of treatment combinations. In comparisons within survivors, no group stands out as having a higher risk of insulin resistance than others, although those that received alkylating agents plus anthracyclines but no platinum or steroids (mostly solid tumors) were less insulin resistant than other treatment groups. In comparison to siblings however, exposure to platinum + CRT was associated with the most significant risk of being more insulin resistant, as was therapy that included steroids. Whole brain radiation has previously been reported to be associated with the development of cardiovascular risk factors(18) and cisplatinum exposure in testicular cancer survivors has been found to be associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular risk factors and coronary artery disease.(19–22) Presumably, in survivors exposed to both CRT and platinum, the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes may be even greater. Due to relatively small numbers of subjects who received cranial radiation and the heterogeneity of fields and doses we were not able to examine the potential differential impact radiation dose may have on the development of insulin resistance or cardiovascular risk factors.

One of the most striking findings that likely contributes to insulin resistance, is the effect that treatment exposures had on reducing TLM. In comparisons with individual agents, and in the tree-derived combinations, a pattern of reduced TLM was found. This was most pronounced in the group receiving platinum plus CRT compared to all other treatment combinations and when compared to siblings. This pattern of decreased TLM, and increased PFM and insulin resistance, is most strongly associated with treatment combinations that included platinum, CRT and/or steroids; and correspondingly is linked to patients treated for brain tumors and leukemia. The mechanisms for these changes in body composition cannot be directly determined from this study. It is possible that some treatment exposures directly lead to decreased muscle mass, but it is also plausible that this may be secondary to reduced levels of physical activity. It has previously been shown that long term restrictions in physical activity and performance limitations are evident in adult survivors of childhood cancer overall(23, 24) as in those specifically treated for either leukemia(25, 26) or CNS tumors.(27) However, given the cross-sectional nature of this study, we are unable to determine the onset of these adverse sequelae, including whether changes in insulin resistance and body composition precede changes in physical performance or vice versa.

This study has several other limitations that impact our ability to draw more definitive conclusions about the impact of specific therapeutic agents or their doses. While the overall sample size was large, the diagnoses and treatments were heterogeneous and could have benefited from larger numbers in each subgroup. It is also very difficult to separate out disease type from treatment, although our data would suggest that the effect on insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk factors was more likely to be the result of the total impact of cancer therapy rather than risks imparted by any single agent. Contemporary cancer therapy is multimodal and involves multiple agents. Thus opportunities will need to be identified in future randomized therapeutic trials that compare treatment arms that differ by the presence of absence of certain agents while incorporating longitudinal follow-up of subsequent changes in cardiovascular risk factors. While there are some potential limitations to the use of siblings as a control group, it could also be suggested that any reported differences in CV risk factors in a situation featuring similar genetic and environmental backgrounds underscore the fact that the divergence in risk profile between CCS and controls is more likely related to cancer or its therapy. Finally, our participation rate (49% of those contacted) was lower than ideal, however considered in the context of a non-therapeutic protocol that required a significant 2 day commitment with a multitude of lengthy test procedures this was felt to be acceptable. Although we did not find any systematic differences between participants and non-participants this does not entirely preclude the possibility of selection biases.

The implications and clinical significance of these findings are that nearly all survivors of childhood cancer are potentially at risk for the development of insulin resistance, lipid abnormalities, and unfavorable changes in body composition. Prior studies in children have shown that low insulin sensitivity is a significant predictor of future increased CV risk.(28) This suggests that the difference in risk factor levels between CCS and the control group will become more apparent with ongoing maturity and aging, and that particular CCS subsets (due to specific treatment combinations) are at particularly great risk. This may help to identify at an earlier time point, CCS who may benefit from more targeted prevention efforts to reduce future cardiovascular disease risk. The treatment combinations typically utilized in survivors treated for leukemia and any patient who has received CNS directed radiation therapy, particularly in combination with platinum agents, have the highest risk of these abnormalities and justify periodic screening of fasting blood sugar and lipid levels. Standard anthropometrics or BMI are not adequate screening to detect loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia) as this would require either whole body DXA or computed tomography (CT) scans. At this point we lack sufficient knowledge regarding the specific role that changes in body composition play in determining cardiovascular risk, and there have not been studies in CCS that have attempted to alter body composition such that any interventions with proven efficacy could be recommended at this time. Nevertheless, recommendations for a prudent diet and exercise such as those from the American Cancer Society(29) or the Centers for Disease Control(30) should be part of our routine recommendations to all survivors. Additionally, management of other risk factors such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia should be aggressively undertaken. Longer term follow-up of survivor cohorts such as those in this study will be necessary in order to determine the trajectory of the abnormalities detected in these young survivors, and the degree to which they contribute to actual cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Funding for this study was provided by the National Institutes of Health: NCI/NIDDK: RO1CA113930-01A1 (J.Steinberger); GCRC: M01-RR00400, General Clinical Research Center Program (University of Minnesota); CTSI: NCATS UL1TR000114 and NCRR/NIH (University of Minnesota); and the Children’s Cancer Research Fund (J.Steinberger., K.S. Baker). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors of this manuscript have no conflict of interest to report relevant to this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Neglia JP, Leisenring W, Robison LL, et al. Late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: a summary from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2328–2338. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mertens AC, Liu Q, Neglia JP, Wasilewski K, Leisenring W, Armstrong GT, et al. Causespecific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1368–1379. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reulen RC, Winter DL, Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Stiller CA, Jenney ME, et al. Longterm cause-specific mortality among survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA. 2010;304:172–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulrooney DA, Yeazel MW, Kawashima T, Mertens AC, Mitby P, Stovall M, et al. Cardiac outcomes in a cohort of adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: retrospective analysis of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Bmj. 2009;339:b4606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talvensaari KK, Lanning M, Tapanainen P, Knip M. Long-term survivors of childhood cancer have an increased risk of manifesting the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3051–3055. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.8.8768873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talvensaari K, Knip M. Childhood cancer and later development of the metabolic syndrome. Ann Med. 1997;29:353–355. doi: 10.3109/07853899708999360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuver J, Smit AJ, Postma A, Sleijfer DT, Gietema JA. The metabolic syndrome in long-term cancer survivors, an important target for secondary preventive measures. Cancer Treat Rev. 2002;28:195–214. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(02)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Yasui Y, Fears T, Stovall M, et al. Obesity in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;17:1359–1365. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurney JG, Sibley SD, O'Leary M, Ness KK, Baker KS. Metabolic syndrome and growth hormone deficiency in adult survivors of childhood leukemia. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2005;44:565. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farooki A, Schneider SH. Insulin resistance and cancer-related mortality. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1628–1629. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9637. author reply 9–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinberger J, Sinaiko AR, Kelly AS, Leisenring WM, Steffen LM, Goodman P, et al. Cardiovascular risk and insulin resistance in childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr. 2012;160:494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moran A, Jacobs DR, Steinberger J, Hong CP, Prineas R, Luepker R, et al. Insulin resistance during puberty: results from clamp studies in 357 children. Diabetes. 1999;48:2039–2044. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.10.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook S, Weitzman M, Auinger P, Nguyen M, Dietz WH. Prevalence of a metabolic syndrome phenotype in adolescents: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2003;157:821–827. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356–359. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breiman L, Friedman JH, Olshen RA, Stone CJ. Classification and Regression Trees. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth International Group; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudson MM, Neglia JP, Woods WG, Sandlund JT, Pui CH, Kun LE, et al. Lessons from the past: opportunities to improve childhood cancer survivor care through outcomes investigations of historical therapeutic approaches for pediatric hematological malignancies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:334–343. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green DM, Kun LE, Matthay KK, Meadows AT, Meyer WH, Meyers PA, et al. Relevance of historical therapeutic approaches to the contemporary treatment of pediatric solid tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1083–1094. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurney JG, Ness KK, Sibley SD, O'Leary M, Dengel DR, Lee JM, et al. Metabolic syndrome and growth hormone deficiency in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2006;107:1303–1312. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman DR, Schaffer WL, Steingart RM. Late cardiovascular toxicity following chemotherapy for germ cell tumors. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2012;10:537–544. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fung C, Vaughn DJ. Complications associated with chemotherapy in testicular cancer management. Nature reviews Urology. 2011;8:213–222. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gospodarowicz M. Testicular cancer patients: considerations in long-term follow-up. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2008;22:245–255. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haugnes HS, Aass N, Fossa SD, Dahl O, Klepp O, Wist EA, et al. Components of the metabolic syndrome in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2007;18:241–248. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ness KK, Wall MM, Oakes JM, Robison LL, Gurney JG. Physical performance limitations and participation restrictions among cancer survivors: a population-based study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ness KK, Bhatia S, Baker KS, Francisco L, Carter A, Forman SJ, et al. Performance limitations and participation restrictions among childhood cancer survivors treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: the bone marrow transplant survivor study. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2005;159:706–713. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ness KK, Hudson MM, Pui CH, Green DM, Krull KR, Huang TT, et al. Neuromuscular impairments in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: associations with physical performance and chemotherapy doses. Cancer. 2012;118:828–838. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ness KK, Baker KS, Dengel DR, Youngren N, Sibley S, Mertens AC, et al. Body composition, muscle strength deficits and mobility limitations in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:975–981. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ness KK, Morris EB, Nolan VG, Howell CR, Gilchrist LS, Stovall M, et al. Physical performance limitations among adult survivors of childhood brain tumors. Cancer. 2010;116:3034–3044. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinaiko AR, Steinberger J, Moran A, Hong CP, Prineas RJ, Jacobs DR., Jr Influence of insulin resistance and body mass index at age 13 on systolic blood pressure, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol at age 19. Hypertension. 2006;48:730–736. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000237863.24000.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, Schwartz AL, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:243–274. doi: 10.3322/caac.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. [cited 2013 May 30];Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 2010 Available from: http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/dgas2010-policydocument.htm.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.