Abstract

Background

Higher serum levels of magnesium (Mg(2+)) may contribute to improved outcome following ischemic stroke, and this may be related to vessel recanalization. Patients with low or normal serum magnesium levels during the acute phase of ischemic stroke may be more susceptible to neurologic deterioration and worse outcomes.

Methods

All patients who presented to our center within 48hrs of acute ischemic stroke (07/2008-12/2010) were retrospectively identified. Patient demographics, laboratory values, and multiple outcome measures, including neurologic deterioration (ND), were compared across admission serum Mg(2+) groups as well as change in Mg(2+) from baseline to 24hr groups.

Results

Three hundred thirteen patients met inclusion criteria (mean age 64.8 years, 42.2% female, 64.0% black). Mg(2+) groups at baseline were not predictive of poor functional outcome, death or discharge disposition. Patients whose serum Mg(2+) decreased during the first 24hrs of admission were also not at greater odds of ND or poor outcome measures compared to patients with unchanging or increasing Mg(2+) levels.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that patients who have low Mg(2+) at baseline or a reduction in Mg(2+) 24hrs after admission are not at a higher risk of experiencing ND or poor short-term outcome. Ongoing prospective interventional trials will determine if hyperacute aggressive magnesium replacement affords neuroprotection in stroke.

Keywords: stroke, ischemia, magnesium, neurologic deterioration, neuroprotection

BACKGROUND

Magnesium (Mg(2+)) ions are known to block glutamatergic n-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in the central nervous system during instances of glutamate neurotoxicity(1) such as acute ischemic stroke.(2) Low Mg(2+) at the time of stroke may accelerate penumbral compromise and result in more severe stroke presentations(3) or early neurologic deterioration if not replaced with magnesium therapy.(4) Few studies have evaluated the impact of baseline Mg(2+) on stroke outcome.(3, 5, 6) The role of serum Mg(2+) or magnesium replacement in ischemic recovery, however, remains controversial and deserves further inquiry.(3, 5) Clinical trials have demonstrated the safety of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) infusion in ischemic stroke patients(7) and suggested that MgSO4 administration offers a therapeutic advantage.(8) Although magnesium infusion within 12 hours of stroke did not confer a survival or morbidity benefit in The Intravenous Magnesium Efficacy in Acute Stroke (IMAGES) trial,(9) the ongoing Field Administration of Stroke Therapy - Magnesium (FAST-MAG) trial is investigating the benefit of ultra-early intravenous magnesium administration.(10) In the present study, we examine the relationship between serum Mg(2+) at presentation, and change in serum Mg(2+) at 24 hours with stroke severity and short-term functional outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

METHODS

Patients

We conducted a retrospective analysis of acute ischemic stroke admitted to our center between July 1, 2008 and December 31, 2010. Eligible patients were identified retrospectively from a prospectively collected stroke registry as previously described.(11) Admitted patients who did not have serum Mg(2+) assessed within 12 hours of presentation, experienced the index stroke after being admitted for a reason other than stroke, were admitted >48 hours after stroke symptoms onset, or had an unknown time of stroke onset were excluded.

Variable definitions

Baseline demographics, clinical and laboratory values, and stroke etiology according to the Trial of org 10172 in acute stroke treatment (TOAST)(12) were collected. Admission serum Mg(2+) level was defined as quantified serum Mg(2+) from a venous blood sample drawn within 12 hours of emergency department arrival. Serum Mg(2+) was also collected at 24 hours. In our clinical setting, serum Mg(2+) ≤2.0 mg/dL is considered low. We further classified patients into dichotomous groups comparing patients whose Mg(2+) was lower at 24 hours than at admission. Outcomes were compared among patients with low Mg(2+) and patients with normal-to-high Mg(2+). Outcomes were further assessed according to whether their Mg(2+) was lower at 24 hours than admission. Outcomes included length of hospital stay (LOS), neurologic deterioration (ND, defined as an increase in National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score of ≥2 points in a 24-hour period),(13) short-term neurologic impairment as measured by the discharge NIHSS score, short-term functional disability as measured by discharge modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score,(14, 15) unfavorable discharge disposition (i.e. disposition that to a place other than home or inpatient rehabilitation), and all-cause in-hospital mortality.

A secondary analysis of patients with Mg(2+) replacement (≥1 gram of intravenous magnesium sulfate) was conducted where we divided the patients into 4 subgroups: 1) Patients who did not receive Mg(2+) replacement whose admission serum Mg(2+) was >2 mg/dL; 2) Patients who did receive Mg(2+) replacement whose admission serum Mg(2+) was >2 mg/dL; 3) Patients who did not receive Mg(2+) replacement whose admission serum Mg(2+) was ≤2 mg/dL; 4) Patients who did receive Mg(2+) replacement whose admission serum Mg(2+) was ≤2 mg/dL. These four groups were used to assess the change in NIHSS measured at baseline, 24 hours and at discharge.

Statistics

Continuous variables were reported as mean +/− the standard deviation when the distribution was normal and median with range for non-normal distributions. Differences in frequencies of categorical variables were assessed by Pearson’s chi-square test or, if assumptions were not met, by Fisher’s Exact Test. Differences in distributions of continuous variables were assessed using Student’s t-test for normally distributed variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-normally distributed variables. Random effects mixed models were used to assess change in NIHSS over time for the four Mg(2+)/magnesium replacement groups, adjusting for intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (IV tPA) use. Logistic regression models were used to assess low versus normal Mg(2+) as well as Mg(2+) lower at 24 hours versus Mg(2+) better at 24 hours and the association with poor functional outcome, unfavorable discharge disposition and death. An alpha of 0.05 was considered significant. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made since this was an exploratory analysis.(16) This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Study population

Of the 596 consecutive patients admitted to our center with acute ischemic stroke, 111 were excluded because serum Mg(2+) levels were not checked within 12 hours of emergency department arrival, 42 excluded due to stroke experienced after admission, 29 because these patients did not arrive at our emergency department until >48hrs after stroke symptoms onset, and 162 due to unknown time of stroke onset. These are not mutually exclusive criteria, leaving 313 patients included in the analyses (mean age 64.8 years, 42.2% female, 64.0% Black). Of the patients included, 181 (57.8%) were found to have low serum Mg(2+) levels at admission. There were no significant differences in age, gender, past medical history, stroke etiology, or severity of stroke between patients with low admission Mg(2+) versus patients with normal-to-high serum Mg(2+) (data not shown). A significantly smaller percentage of patients with low Mg(2+) on admission were active smokers compared to the percentage of patients with normal-to-high Mg(2+) on admission (6.3% vs. 28.4%, p=0.0277). Patient demographics according to change in serum Mg(2+) from admission to 24 hours are shown in Table 1. More patients were replaced with IV Mg(2+) in the group where Mg(2+) remained the same or was higher at 24 hours (p<0.0001). The median change in serum Mg(2+) from baseline to 24 hours for the group who experienced a decrease in Mg(2+) levels was −0.2 mg/dL (range −1.6 to −0.1) compared to an increase in 0.1 mg/dL (range 0 to 1.0 mg/dL) for the group who did not experience a decrease in Mg(2+) levels (p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic information for all patients with acute ischemic stroke, according to change in serum Mg(2+) from admission to 24 hours.

| 24hr Mg(2+) < admission Mg(2+) (N=139) |

24hr Mg(2+) > admission Mg(2+) (N=117) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median years (range) | 68(26-97) | 63 (19-93) | 0.0642 |

| Black, n (%) | 93 (66.9%) | 76 (64.9%) | 0.5864 |

| Gender, n (%) female | 59 (42.5%) | 49 (41.9%) | 0.9273 |

| History of Stroke, n (%) | 55 (39.6%) | 49 (41.9%) | 0.7075 |

| History of Diabetes, n (%) | 43 (31.4%) | 40 (34.5%) | 0.6012 |

| History of Hypertension, n (%) | 101 (74.3%) | 89 (76.7%) | 0.6514 |

| Active smoker, n (%) | 40 (29.4%) | 28 (24.4%) | 0.3684 |

| TOAST classification, n (%) | 0.3969 | ||

| Cardioembolic | 39 (28.1%) | 36 (30.8%) | |

| Large Vessel Disease | 38 (27.4%) | 24 (20.5%) | |

| Small Vessel Disease | 24 (17.3%) | 24 (20.5%) | |

| No cause | 29 (20.9%) | 23 (19.7%) | |

| More than one cause | 3 (2.2%) | 2 (1.7%) | |

| Other | 6 (4.3%) | 8 (5.8%) | |

| Admission NIHSS, median score (range) |

7 (0-34) | 6 (0-31) | 0.5790 |

| Admission Serum Glucose, mean (range) |

116 (78-663) | 126 (70-466) | 0.2145 |

| Admission Serum Calcium, mean (range) |

9.1 (6.4-10.7) | 9 (5-11) | 0.0013 |

| Magnesium Replaced, n (%) | 8 (5.8%) | 38 (32.5%) | <0.0001 |

| IV tPA, % treated | 59 (42.8%) | 48 (41.0%) | 0.7805 |

Abbreviations: Mg(2+), magnesium; TOAST, Trial of org 10172 in acute stroke treatment; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score; IV tPA, intravenous tissue plasminogen activator.

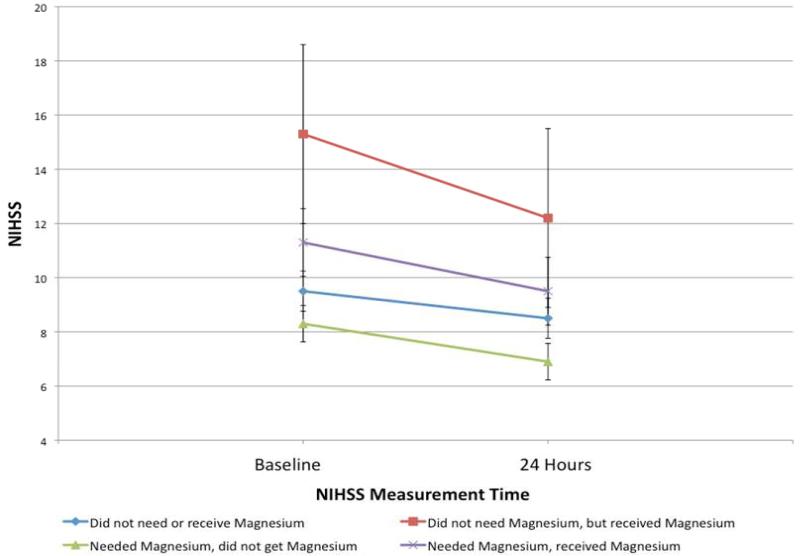

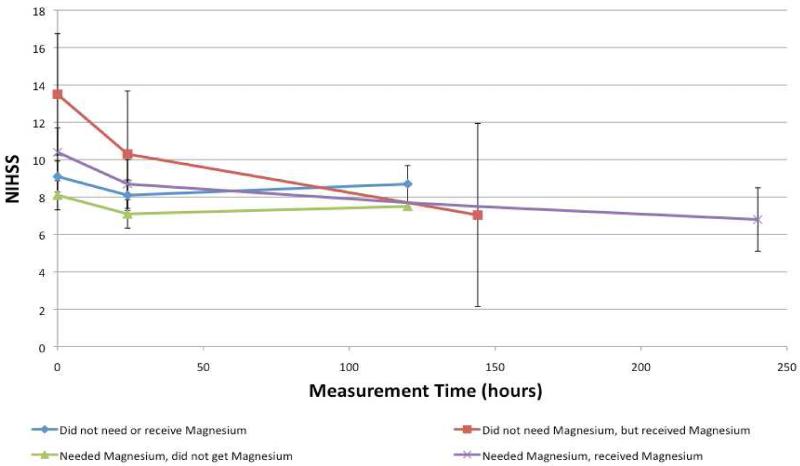

Random effects model results for change in NIHSS over time

We investigated the patients subgrouped by magnesium replacement and dichotomized Mg(2+) on admission and how this affected any change in NIHSS from baseline to 24 hours to discharge. Figure 1 illustrates how NIHSS changes from baseline to 24 hours in patients in these four groups, without adjusting for any additional variables (p=0.4727). The change of NIHSS over the entire hospitalization for the four groups after adjusting for IV tPA use showed similar results (Figure 2), but remained non-significant (p=0.7146).

Figure 1.

Assessing the crude relationship for NIHSS from Baseline to 24 hours by magnesium category.

Received magnesium indicates patient received ≥1 gram of intravenous magnesium sulfate within 24 hours of time last seen normal.

Abbreviations: NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Figure 2.

Assessing the change in NIHSS, adjusted for IV tPA use, over time based on Mg(2+) level and magnesium replacement.

Received magnesium indicates patient received ≥1 gram of intravenous magnesium sulfate within 24 hours of time last seen normal.

Abbreviations: NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; IV tPA, intravenous tissue plasminogen activator; Mg(2+), serum magnesium level.

Poor functional outcome, discharge disposition, and death

When evaluating patient outcomes, a higher percentage of patients with low baseline Mg(2+) were discharged to an unfavorable discharge disposition compared to patients with normal-to-high serum Mg(2+), but this difference did not reach statistical significance (35.3% vs. 19.5%, p=0.1396). There were no significant differences across any outcome measure, including neurologic deterioration, between patients with low versus normal-to-high baseline Mg(2+) level (data not shown) or according to change in Mg(2+) level at 24 hours versus admission (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcome measures for all patients, according to Magnesium change at 48 hours.

| Mag Lower 24 hours than admission (N=139) |

Mag not lower at 24 hours than admission (N=117) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of Stay, median days (range) | 5 (1-43) | 5 (1-39) | 0.8185 |

| Discharge NIHSS, median score (range) | 4 (0-42) | 3 (0-42) | 0.7585 |

| Discharge mRS, median score (range) | 3 (0-6) | 3 (0-6) | 0.2183 |

| Neurologic deterioration, n (%) | 46 (33.3%) | 44 (37.6%) | 0.4767 |

| Poor functional outcome, n (%) | 88 (63.3%) | 67 (57.3%) | 0.3243 |

| Unfavorable discharge disposition*, n (%) | 26 (18.8%) | 25 (21.7%) | 0.5672 |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 12 (8.6%) | 5 (4.3%) | 0.0785 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score; mRS, modified Rankin Scale score.

Unfavorable discharge disposition includes discharge to long-term acute care facility, skilled nursing facility, hospice, and in-hospital mortality.

Crude logistic regression models were not significant investigating low Mg(2+) at admission as a predictor for poor functional outcome (OR=0.997 95%CI 0.815-1.220), unfavorable discharge disposition (OR=0.826 95%CI 0.643-1.062, p=0.1358) or death (OR=0.839 95%CI 0.575-1.225, p=0.3635). When assessed as a continuous variable, baseline Mg(2+) levels were not associated with poor functional outcome (OR=1.42, 95%CI 0.66-3.05, p=0.3626), unfavorable disposition (OR=1.27, 95%CI 0.49-3.26, p=0.6189) or death (OR=1.53, 95%CI 0.37-6.36, p=0.5588). Crude logistic regression models were also not significant for investigating Mg(2+) at 24 hours lower than admission as a predictor for poor functional outcome (OR=1.288 95%CI 0.779-2.130, p=0.3246), unfavorable discharge disposition (OR=0.836 95%CI 0.452-1.546, p=0.5674), or death (OR=2.117 95%CI 0.723-6.194, p=0.1711).

DISCUSSION

In our population, low admission serum Mg(2+) levels—as defined by our clinical standards (serum Mg(2+) ≤2.0 mg/dL)—and reductions in Mg(2+) level at 24 hours were not associated with worse clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke. The difference in median Mg(2+) level in the groups may be below the clinically meaningful threshold. In both the dichotomized analysis of low versus normal-to-high admission serum Mg(2+) and the analysis based on 24 hour Mg(2+) change, we observed no significant differences in history of hypertension, in contrast to prior studies linking low serum Mg(2+) to hypertension.(17, 18) Patients with low Mg(2+) levels at admission were also less likely to be tobacco users, a finding consistent with one prior study documenting higher Mg(2+) levels among smokers versus non-smokers, the etiology of which is still unclear.(19)

Despite there not being statistical significance, there was a relationship between Mg(2+) levels and magnesium replacement on NIHSS over time. Groups who were replaced, regardless of Mg(2+) on admission, had a sharper decrease in NIHSS from admission to discharge. We suspect that the combination of modest doses of magnesium sulfate administered in the presence of normal or elevated serum Mg(2+) may produce neuroprotective serum levels of Mg(2+). The same neuroprotective levels of Mg(2+) may not be sufficiently reached when the starting Mg(2+) levels are lower, despite the modest doses of intravenous magnesium replacement. Due to sample size constraints we suspect this non-significant test from the random effects mixed models would be significant with a larger sample size. We were limited by the small cell count in one of the groups, which likely contributed to the non-significance of the p value. Although inconsistently shown in the literature,(7-10) prevention of hypomagnesemia, or at least the detectable drop in Mg(2+) levels may provide some therapeutic benefit for patients with AIS. These results require validation in a larger population.

Our study is limited by its retrospective approach. In addition, our small sample size may prohibit us from detecting statistically significant differences in outcomes of patients who receive greater or lesser doses of Mg(2+) replacement (e.g. 1 gram vs. 2 gram or more of intravenous magnesium sulfate). Given that we did not adjust for multiple comparisons, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of our findings may be due to chance. We recommend adjustments for multiple testing in prospective studies.(16) Our patient population is unique and may not reflect the demographic characteristics of the nation as a whole, making our results potentially difficult to generalize. Our assessment in change in Mg(2+) levels without regard to renal function or fluid replacement, may have contributed to alterations in Mg(2+) regulation and serum levels. Impaired renal function can lead to retention(21) or wasting(22) of Mg(2+) which may lead to normal serum levels of serum Mg(2+) despite an underlying pathophysiologic state. Further, fluid replacement or diuresis during the first 24 hours of hospitalization may have artificially impacted our observed change in Mg(2+) homeostasis during the acute phase of stroke. Exclusion of patients who underwent diuresis or fluid replacement would make our results less generalizable across a larger stroke population, as many hospitalized patients with stroke will receive fluid replacement as medically necessary.

Penumbral death can extend beyond the first few hours of acute ischemic stroke and is a target of neuroprotection. Destructive processes may be more likely to occur in the absence of adequate magnesium stores, which might otherwise suppress excitotoxic NMDA receptor activity. An investigation involving a larger population is necessary to further characterize early shifts in stroke severity in and the long-term effect of magnesium level changes in response to aggressive magnesium replacement during the hyperacute phase of ischemic stroke.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to recognize Inmaculada Aban, PhD, for her statistical support and in the review of this manuscript; and Kamal Shah, MD, for assistance with data collection and management.

DISCLOSURES

The project described was supported by Award Numbers 5 T32 HS013852-10 from The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), 3 P60 MD000502-08S1 from The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH) and 13PRE13830003 from the American Heart Association. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the AHRQ, AHA or the NIH. James E. Siegler received a student scholarship in stroke and cerebrovascular disease through the American Heart Association for the purpose of this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Choi DW, Koh JY, Peters S. Pharmacology of glutamate neurotoxicity in cortical cell culture: attenuation by NMDA antagonists. J Neurosci. 1988 Jan;8(1):185–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-01-00185.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muir KW. Magnesium in stroke treatment. Postgrad Med J. 2002 Nov;78(925):641–5. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.925.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cojocaru IM, Cojocaru M, Burcin C, Atanasiu NA. Serum magnesium in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Rom J Intern Med. 2007;45(3):269–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntosh TK, Vink R, Yamakami I, Faden AI. Magnesium protects against neurological deficit after brain injury. Brain Res. 1989 Mar 20;482(2):252–60. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ovbiagele B, Liebeskind DS, Starkman S, Sanossian N, Kim D, Razinia T, et al. Are elevated admission calcium levels associated with better outcomes after ischemic stroke? Neurology. 2006 Jul 11;67(1):170–3. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223629.07811.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lampl Y, Gilad R, Geva D, Eshel Y, Sadeh M. Intravenous administration of magnesium sulfate in acute stroke: a randomized double-blind study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2001 Jan-Feb;24(1):11–5. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200101000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muir KW, Lees KR. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial of intravenous magnesium sulfate in acute stroke. Stroke. 1995 Jul;26(7):1183–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldman RS, Finkbeiner SM. Therapeutic use of magnesium sulfate in selected cases of cerebral ischemia and seizure. N Engl J Med. 1988 Nov 3;319(18):1224–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811033191813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muir KW, Lees KR, Ford I, Davis S. Magnesium for acute stroke (Intravenous Magnesium Efficacy in Stroke trial): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004 Feb 7;363(9407):439–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15490-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saver JL, Kidwell C, Eckstein M, Starkman S. Prehospital neuroprotective therapy for acute stroke: results of the Field Administration of Stroke Therapy-Magnesium (FAST-MAG) pilot trial. Stroke. 2004 May;35(5):e106–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000124458.98123.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegler JE, Boehme AK, Dorsey AM, Monlezun D, George AJ, Bockholt HJ, et al. A Comprehensive Stroke Center Patient Registry: Advantages, Limitations, and Lessons Learned. Med Stud Res J. 2013 doi: 10.15404/msrj.002.002.spring/03. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams HP, Jr., Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993 Jan;24(1):35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegler JE, Boehme AK, Kumar AD, Gillette MA, Albright KC, Martin-Schild S. What Change in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale Should Define Neurologic Deterioration in Acute Ischemic Stroke? J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012 Jun 21; doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rankin J. Cerebral vascular accidents in patients over the age of 60. II. Prognosis. Scott Med J. 1957 May;2(5):200–15. doi: 10.1177/003693305700200504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988 May;19(5):604–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.5.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing--when and how? J Clin Epidemiol. 2001 Apr;54(4):343–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohira T, Peacock JM, Iso H, Chambless LE, Rosamond WD, Folsom AR. Serum and dietary magnesium and risk of ischemic stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009 Jun 15;169(12):1437–44. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resnick LM, Bardicef O, Altura BT, Alderman MH, Altura BM. Serum ionized magnesium: relation to blood pressure and racial factors. Am J Hypertens. 1997 Dec;10(12 Pt 1):1420–4. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eliasson M, Hagg E, Lundblad D, Karlsson R, Bucht E. Influence of smoking and snuff use on electrolytes, adrenal and calcium regulating hormones. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1993 Jan;128(1):35–40. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1280035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKee JA, Brewer RP, Macy GE, Borel CO, Reynolds JD, Warner DS. Magnesium neuroprotection is limited in humans with acute brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 2005;2(3):342–51. doi: 10.1385/NCC:2:3:342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coburn JW, Popovtzer MM, Massry SG, Kleeman CR. The physicochemical state and renal handling of divalent ions in chronic renal failure. Arch Intern Med. 1969 Sep;124(3):302–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis BB, Preuss HG, Murdaugh HV., Jr. Hypomagnesemia following the diuresis of post-renal obstruction and renal transplant. Nephron. 1975;14(3-4):275–80. doi: 10.1159/000180457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]