Abstract

The past seven decades have seen remarkable shifts in the nutritional scenario in India. Even up to the 1950s severe forms of malnutrition such as kwashiorkar and pellagra were endemic. As nutritionists were finding home-grown and common-sense solutions for these widespread problems, the population was burgeoning and food was scarce. The threat of widespread household food insecurity and chronic undernutrition was very real. Then came the Green Revolution. Shortages of food grains disappeared within less than a decade and India became self-sufficient in food grain production. But more insidious problems arising from this revolution were looming, and cropping patterns giving low priority to coarse grains and pulses, and monocropping led to depletion of soil nutrients and ‘Green Revolution fatigue’. With improved household food security and better access to health care, clinical manifestations of severe malnutrition virtually disappeared. But the decline in chronic undernutrition and “hidden hunger” from micronutrient deficiencies was slow. On the cusp of the new century, an added factor appeared on the nutritional scene in India. With steady urban migration, upward mobility out of poverty, and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle because of improvements in technology and transport, obesity rates began to increase, resulting in a dual burden. Measured in terms of its performance in meeting its Millennium Development Goals, India has fallen short. Despite its continuing high levels of poverty and illiteracy, India has a huge demographic potential in the form of a young population. This advantage must be leveraged by investing in nutrition education, household access to nutritious diets, sanitary environment and a health-promoting lifestyle. This requires co-operation from all the stakeholders, including governments, non government organizations, scientists and the people at large.

Keywords: Dual nutrition burden, green revolution, micronutrients, nutrition, supplementation

During the past six to seven decades there has been a remarkable change in the pattern of nutrition-related problems in India. Looking back, we can see how far we have come. But, looking forward, we see that the road ahead is long and challenging.

LOOKING BACK

1940s to 1960s

In the 1940s and 1950s, the major nutritional diseases prevalent in large sections of the population were kwashiorkar (acute protein-energy malnutrition), keratomalacia (attributable to severe vitamin A deficiency), beri-beri (arising from vitamin B1 deficiency) and pellagra (nicotinic acid deficiency). Over the course of two to three decades, the most florid manifestations of these malnutrition diseases virtually disappeared. How did this happen in a poor country with a burgeoning population and limited resources? These “miraculous changes” did not come about through distribution of synthetic vitamins, drugs or special formulations, but through a better understanding of the diseases themselves, and through local-level health and diet-based interventions. There was a strong move to introduce a protein supplementation programme with fish concentrates and wheat fortification with lysine to tackle kwashiorkar. Indian nutrition scientists argued against these moves, and were ultimately proved to be right.

The banishment of beri-beri is a classic example of a common sense approach. It was known that beri-beri was caused by vitamin B1 deficiency, and there were some who advocated vitamin B1 supplementation. However, a look at ground realities gave a clue to the solution. The people living in a region (which is now Andhra Pradesh) ate milled and highly polished rice as their staple diet. Beri-beri was rampant there. The people living further south were eating rice that was only partly milled and not polished. There was no beri-beri in this population. A policy decision was made that the rice being accessed by the low socio-economic groups would not be milled and polished. Beri-beri soon died a natural death. Sometimes unforeseen factors unleashed by the developmental process have worked tangentially but effectively to help in changing the epidemiology of nutritional diseases. An example is the disappearance of pellagra, a disease associated with nicotinic acid deficiency. Populations that consumed the millet jowar (sorghum) almost exclusively as their staple diet were prone to pellagra. Research showed that the high leucine content in this millet inhibited the absorption of nicotinic acid. But scientists did not resort to nicotinic acid supplementation. Instead, they advised these populations not to rely solely on jowar but to vary their diets by including other cereals and millets. Meanwhile, when the Green Revolution arrived in the late 1960s, the price of rice and wheat supplied through ration shops fell to low and readily affordable levels. People switched to eating rice, and soon thereafter pellagra perished.

Diseases have natural histories of their own. The natural histories of the severe nutritional diseases hold lessons and valuable insights for nutritionists. They must remain ever alert to local conditions and changing environments, to anticipate the nutritional fallouts1.

During the British regime, India experienced recurrent famines that killed several hundreds of thousands of people. The casualties during the Great Bengal Famine were said to have been greater than the total casualties of all the Allied armed forces in World War II. After Independence in 1947, major famines were no longer seen, but the threat of starvation still loomed over large sections of the people. Malnutrition continued to haunt the poor, though there has been a reduction in severity of the manifestations. Alongside these problems, the population of Independent India surged at a rate that dwarfed the population growth of the previous 200 years. By the 1960s, India was faced with fast-emptying grain baskets, and the prospect of having to import food to ward off famine.

Green Revolution

With the timely advent of the Green Revolution, this threat was staved off. Intensive cultivation of high-yielding varieties of rice and wheat filled the granaries. But, not surprisingly, the Green Revolution had some deleterious side-effects. The heavy use of chemical fertilizers and intensive cultivation practices depleted soil fertility in many areas, robbing it of valuable and essential micronutrients and thereby compromising the nutritional quality of the foods grown in these soils. Importantly, the near-exclusive emphasis on rice and wheat resulted in the virtual disappearance of millets from the diets of large sections of the population. This was unfortunate because millets are valuable as adjunct foods, not only from the nutritional point of view but also because these have a low glycaemic index. For instance, the rise in blood glucose levels is much less with a ragi-based diet than with a rice-based diet2. While it is true that the “epidemic” of diabetes that we are witnessing today is multifactorial in origin, sharp changes in long-held dietary patterns (abandonment of millets from the diet and fewer complex carbohydrates) may have contributed to the problem.

1970s to 1990s

While the food scarcity problem was largely solved by the 1970s, the malnutrition problem was not. The Green Revolution had focussed almost exclusively on rice and wheat. The result was a relative neglect of pulses and horticultural products. Pulses are an important source of protein in Indian diets, particularly for vegetarians. There has been a progressive escalation in the cost of all the pulses; these are generally not being distributed under the subsidized Public Distribution System, and are, therefore, not within the purchasing power of the poor. Again, while India is among the largest milk producers in the world, the milk intake of the people who need it the most (young children and pregnant women in the poor socio-economic groups) is low3. Vegetables and fruits are perishables, and in the absence of effective storage, preservation and transportation, the prices are unstable and the availability uncertain. With all these factors coming into play, the diets of the average Indian household did not show any significant improvement over the last few decades of the century.

How was this unsatisfactory nutritional situation manifested? The social development indices of the late 1990s continued to be unflattering. The rates of maternal mortality, infant mortality and under-five mortality were still unacceptably high. About one-third of newborn infants were of low birth weight and there was a distressingly high prevalence of wasting and stunting in children4. Maternal anaemia was so widespread as to be termed endemic.

The role of micronutrients

The period from the 1970s to the 1990s saw added focus on the role of micronutrients. Of course, nutrition scientists even in the earlier part of the century had seen at first hand the health problems caused by deficiencies of vitamin A, iron, and iodine. But the roles of other micronutrients such as zinc, folic acid, magnesium, selenium and vitamin D, among others, in processes ranging from growth and development of children to the functioning of the immune system started receiving greater attention. The increasing evidence that micronutrients function synergistically within the human system, and that stand-alone supplementation of one or the other micronutrient would have only limited benefits, made it even clearer that only food-based approaches could achieve nutritional balance in the long run. For instance, India's experience with decades of iron supplementation programmes in pregnant women has been less than satisfactory, with the levels of anaemia remaining stubbornly high in this vulnerable group even in the face of supplementation. The challenge, therefore, is to increase the intake, bioavailability and absorption of iron in the system. It has been reported that the presence of some other micronutrient(s) like vitamin C enhances iron absorption5. This continues to be an important area of research. Meantime, the ideal approach to tackle micronutrient deficiency would be to provide supplements only where and when absolutely necessary, fortify foods where the technology is simple, sustainable and demonstrably safe, and push steadily for a diet-based approach involving a variety of locally available foods.

Factors that influenced the changing nutritional scenario

Throughout the latter part of the twentieth century, certain trends associated with the overall development process in the nation began to gather momentum:

-

(i)

Population growth: As death rates fell, birth rates continued to be high, and some of the earlier killer diseases began to be tackled, the population grew rapidly. Fortunately, the Green Revolution staved off the threat of foodgrain shortages.

-

(ii)

Urban migration: As the cities developed and offered more opportunities for employment, and agriculture became gradually less labour-intensive, people moved in large numbers into the cities. This phenomenon resulted in the mushrooming of urban slums and sharp changes in the lifestyles and diets of the erstwhile rural people.

-

(iii)

Mechanisation and labour-saving devices: The energy expenditure of almost all sections of the population fell substantially as lifestyles became more sedentary.

Dual nutrition burden

Not surprisingly, therefore, in the last decades of the twentieth century, a new nutritional problem began to emerge in India - the problem of overnutrition and obesity. This was a phenomenon that had already entrenched itself in developed countries, with increasing mechanisation, changing lifestyles, and fast foods. All these factors inevitably made their way into India as well, particularly in the urban areas, with predictable results. Within a single generation, the prevalence of obesity rose substantially and, by the late 1990s, the trend was inexorably upwards. This problem constituted a dual burden - persistent undernutrition alongside emerging overnutrition.

The twist to the tale as far as India and other countries in the region are concerned is that this sharp rise in obesity is a manifestation of “nutritional transition”. Children who experienced intrauterine growth retardation, resulting in low birth weight, appear to be programmed to develop along a lower growth trajectory. Paradoxically, however, many overweight and obese adults are those who had experienced calorie deprivation and faltering growth in early childhood due to poverty and deprivation. Subsequently, with better access to food and low physical activity, they fall prey to the opposite problem of obesity. Barker's hypothesis6 linking low birth weights and early nutritional deprivation with obesity in adulthood, with its accompanying metabolic disorders, focuses the spotlight on the crucial importance of a “life-cycle approach” to nutrition. The early signs of malnutrition throw long shadows well into adulthood. Indeed the consequences of metabolic imbalance are being felt even earlier in life, with obesity becoming more and more prevalent even in childhood.

Overweight and obesity are health risks by themselves. Added to this is the associated risk of developing chronic lifestyle diseases such as diabetes and coronary heart disease. This trend has serious consequences for the health and quality of life of adults in the prime of life; it is also a tremendous drain on national public health resources, which have now to be used to defend enemies on both flanks. Therefore, by the end of the century, nutritionists and policy planners were battling the old enemy, undernutrition and micronutrient deficiency, by stepping up food availability, fine-tuning large, national level programmes of supplementation and nutrition support, universalizing a mid day meal (MDM) programme for school children, researching potential inputs that could make a dent in stubborn problems, and trying to step up governance to meet Millennium Development Goals relating to social indicators of development. They were also just beginning to turn their attention to the new battle against obesity. This is a battle for minds, involving education, awareness building and persuasion, where no handouts or supplementation can help.

The new millennium

We are now more than a decade into the new millennium. During this last decade, the Government of India has attempted to strengthen its social sector programmes and launch new ones:

-

(i)

It has been trying to strengthen its flagship nutrition supplementation programme, the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS), and its nation-wide school feeding programme (Mid day Meal Programme).

-

(ii)

Launched a unique work-guarantee scheme for the vulnerable sections of the population (NREGA). The latter has encountered problems on the ground, and attempts are on to monitor the scheme so as to plug the leaks.

-

(iii)

A Food Security legislation is planned, that aims to put adequate stocks of food grains into every poor Indian household at heavily subsidized prices.

-

(iv)

The widening use of electronic databases and the launch of a programme to give every Indian a unique identity number (UID scheme) are designed to target the government funds and subsidies more efficiently.

-

(v)

Through a new legislation, every Indian child has been given the Right to Education. It is another matter that millions of children and their parents remain unaware of this right and are in no position to exercise it for a variety of reasons.

There have also been some tentative moves towards public-private partnerships for improving social sector programmes such as primary health and primary education, with the involvement of corporates and non government organizations (NGOs). However, these are still on a limited scale.

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

As the new century dawned, globalization had become more than just a concept. It had become reality. Enlightened people everywhere were realising that hunger and malnutrition anywhere on the planet was everyone's concern. In a bid to accelerate development towards a better quality of life for all citizens especially those from poorer segments of population living in developing countries, 193 United Nations Member States and many major international organizations have agreed to achieve by the year 2015 the following Millennium Development Goals: (i) Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger; (ii) Achieve universal primary education; (iii) Promote gender equality and empower women; (iv) Reduce child mortality rates by 2/3rd between 1990-2015; (v) Improve maternal health and reduce maternal mortality by 3/4th between 1990 and 2015; (vi) Prevent further increase in prevalence by 2015 and later reduce prevalence of HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and other diseases; (vii) Ensure environmental sustainability; and (viii) Develop a global partnership for development7.

Setting specific targets and quantifying progress towards these targets has been helpful in identifying areas of weakness and in drawing up report cards.

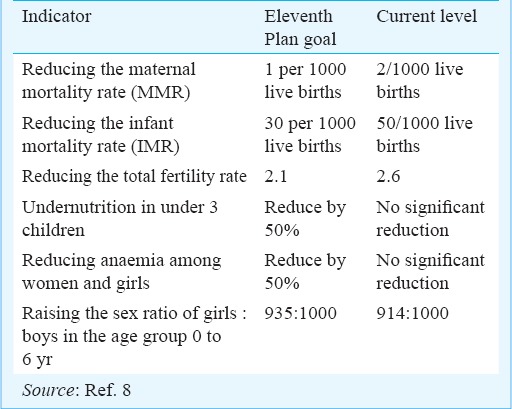

India is a signatory to the Millennium Development Goals and the Eleventh Five Year Plan had set time bound measurable nutrition and health goals taking MDG into account. A brief statement of the goals set and the current status is given in the Table:

Table.

Eleventh Plan goals and current level of achievement

As we can see, India will not meet many of its MDG targets. The problems of low birth weight and maternal anaemia are still worryingly high. Undernutrition leading to poor growth and stunting continues to take its toll on succeeding generations of children. Simultaneously, the problem of obesity and chronic lifestyle diseases is now virtually an “epidemic”. It is estimated that, unless effective interventions are undertaken, the current prevalence of obesity of 10-15 per cent among adults will double over the next two decades4. The number of deaths from cardiovascular diseases (CVD) annually in India is projected to rise from 2.26 million in 1990 to 4.77 million in 20209 with a similar potential for steep increase in risks of cardiovascular disease and diabetes10,11. This constitutes only the proverbial tip of the iceberg, because many people with these conditions may be unaware of these and may not seek medical help. With the growing trend towards sedentary lifestyles, hypertension may become the rule rather than the exception, and start at earlier and earlier ages, especially in urban areas. As we have seen, the link between these diseases and overnutrition is now well established.

It is no surprise, therefore, that the “dual disease burden” runs in parallel with the “dual nutrition burden”. The malnutrition-infection link has long been known, because poor nutritional status affects the immune system and increases vulnerability to infection. Infectious and communicable diseases continue to decimate large numbers of people, particularly children; simultaneously, non communicable, lifestyle diseases such as diabetes and coronary heart disease are rising inexorably. The overnutrition-chronic diseases link has been firmly established towards the latter part of the last century - obesity predisposes to metabolic syndrome and thereby to non communicable diseases. In short, the dual nutrition problem has multiplied the pressure on the public health system and continues to use up scarce resources.

The way forward: changing the nutritional scenario

The key to long-term solutions lies in prevention. This requires a proactive approach. The current programmes are aimed largely at alleviating the effects of poverty and low income, and are, therefore, based on a system of food subsidies and hand-outs. While this is certainly necessary in the present context, the long-term approach should be to empower all households to access their food and health needs and be able to raise their standards of living. This calls for accelerated programmes to improve the quality of our human resources, starting at the root of the problem.

-

(i)

The problem of low birth weight can be solved only by ensuring better maternal nutrition. The weight gain in a woman during pregnancy should be at least 9 to 10 kg for any reasonable expectation of a >2.5 kg baby. Maternal and Child Health Centres should take up strong counselling programmes to help achieve this goal.

-

(ii)

However, maternal nutritional status is itself dependent on nutritional inputs earlier in life. Adolescent girls, many of who are outside the school system, especially in rural areas, should receive intensive non-formal life-skills education focusing on hygiene and sanitation, reproductive health, and child rearing practices. That such programmes can have a visible impact has been demonstrated in an early pilot study12. In the absence of such a structured approach, age-old beliefs and misguided practices continue to flourish and maintain the vicious cycle.

-

(iii)

The national-level nutrition support programmes including the ICDS and the MDM are well-structured and adequately funded. But, inevitably, the performance has been patchy because of sharply differing levels of commitment and competence among States as well as among regions within States. These programmes require local-level monitoring which will be both constructive and supportive. Our academia, especially those in the fields of Nutrition and Public Health in Home Science colleges and Medical colleges are ideally placed to guide and monitor the programmes in their immediate geographical neighbourhood. This hands-on approach by professionals would not only improve the performance parameters, but also raise awareness levels of the professionals as well as of the members of the community. Currently, there is no move towards attempting this.

-

(iv)

Schools are the logical entry point for a preventive approach to nutritional problems. School Health Scouts movement can help through which school children can be agents of change, trained to spread the message of good hygienic and nutritional practices to their homes and communities. Of course, all such programmes would presuppose the existence of a sound, functional school system, which is not the case in many parts of India. However, there is an urgent need to fix the system and get primary education to a more acceptable plane. Only then can it serve as a platform from which programmes of early nutritional education can take off.

-

(v)

With the advent of lifestyle diseases, it has become more important than ever before to stress the importance of physical exercise. Growing urbanization, increasing mechanization in all areas from farms to city roads, and more sedentary occupations are big contributors to the overweight trend. Nutritionists and dieticians must include advice about physical exercise as an important adjunct to their nutrition counselling and messages.

-

(vi)

Infrastructure such as clean water supply and functional toilets are essential to ensuring sanitation and thereby minimize infections. In the absence of infrastructure, awareness-raising is pointless.

-

(vii)

Educating the community about its rights and responsibilities is an essential prerequisite for participatory programmes of nutrition and health. For instance, regular washing of the hands by those who prepare meals and handle children would go a long way in reducing the diarrhoea burden. Health workers should be sufficiently informed and sensitized so that they can raise awareness levels in the community with commitment and empathy.

-

(viii)

Nutritionists need to be aware that the population demographics are becoming increasingly heterogeneous. Old notions based on the “one-size-fits-all” approach have to be abandoned. In the same poor household there may be both obese and wasted individuals. In a well-to-do family there may be persons with micronutrient deficiencies. Lifestyle diseases have begun to invade rural areas as well. Therefore, the trend should be towards a more nuanced approach to nutritional management. There must be a thinner stratification of “target groups” with inputs that are tailored to the needs of these groups. In the field of medicine, there is a growing trend towards “personalized treatment”. While it is impractical to do this in delivering nutritional services, it is important that health and nutrition workers be sensitized to see the people they serve not as an amorphous set of “beneficiaries” but as different human beings with varying requirements.

People are not potential problems; they are potential assets. If India is to reap the demographic harvest of its young population, it must ensure that the quality of the population is good and productive. The nutritional status of the population is a measure of the calibre of the people. Therefore, efforts to change the existing nutritional scenario should be a top priority in the years ahead.

References

- 1.Gopalan C. The changing epidemiology of malnutrition in a developing society; the effect of unforeseen factors. NFI Bull. 1999;20:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gopalan C, Ramanathan MK. Effect of different cereals on blood sugar levels. Indian J Med Res. 1957;45:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau. Technical reports 2006. [accessed on August 26, 2013]. Available from: www.nnmbindia.org/downloads.htm .

- 4.Ramchandran P. Nutrition transition in India 1947-2007. [accessed on August 26, 2013]. Available from: http// www.wcd.nic.in/publications .

- 5.Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR): Nutrient requirements and Recommended Dietary allowances for Indians. [accessed on August 22, 2013]. Available from: icmr.nic.in/final/RDA-2010 .

- 6.Barker DJP. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingston; 1998. Mothers, babies and health in later life. [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNDP Millennium Development Goals. [accessed on August 26, 2013]. Available from: www.undp.org/mdg .

- 8. [accessed on August 26, 2013]. Available from: http://planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/12appdrft/appraoch_12plan.pdf .

- 9.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enas EA, Mohan V, Deepa M, Farooq S, Pazhoor S, Chennikkara H. The metabolic syndrome and dyslipidemia among Asian Indians: a population with high rates of diabetes and premature coronary artery disease. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2007;2:267–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2007.07392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assessment of burden of noncommunicable diseases in India. New Delhi: ICMR; 2006. Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain S, Shivpuri V. New Delhi: Nutrition Foundation of India; 1993. Education for better living of rural adolescent girls (training modules), vol. 1 - Health and nutrition, vol. II - Social awareness. [Google Scholar]