Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether maternal use of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) for treatment of HIV in pregnancy predicts fetal and infant growth.

METHODS

The study population included HIV-uninfected liveborn singleton infants of mothers enrolled in the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol P1025 (born 2002-2011) in the United States and exposed in utero to a combined (triple or more) antiretroviral (ARV) regimen. Infant weight at birth and 6 months was compared between infants exposed and unexposed to tenofovir in utero using two-sample T- and Chi-square tests and multivariable linear and logistic regression models including demographic and maternal characteristics.

RESULTS

Among 2025 infants with measured birth weight, there was no difference between those exposed (N=630, 31%) versus unexposed to tenofovir in mean birth weight (2.75 vs. 2.77 kg, p=0.64), or mean gestational age- and sex-adjusted birth weight z-score (WASZ) (0.14 vs. 0.14, p=0.90). Among 1496 infants followed for 6 months, there was no difference in mean weight at 6 months between tenofovir-exposed (N=457, 31%) and tenofovir-unexposed infants (7.64 vs. 7.59 kg, p= 0.52), or in mean WASZ (0.29 vs. 0.26, p= 0.61). Tenofovir exposure during the 2nd/3rd trimester, relative to no exposure, significantly predicted under-weight (WASZ < 5%) at age 6 months (OR [95% CI]: 2.06 [1.01, 3.95], p=0.04). Duration of tenofovir exposure did not predict neonatal or infant growth.

CONCLUSIONS

By most measures, in utero exposure to tenofovir did not significantly predict infant birth weight or growth through 6 months of age.

Keywords: tenofovir, mother-to-child transmission, infant growth, TDF, HIV, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Routine use of combination antiretroviral drug regimens in pregnancy has resulted in a decline in the rate of maternal to child transmission of HIV from over 20% to less than 1%1,2. Current U.S. guidelines recommend that HIV-infected pregnant women receive a three-drug regimen of two nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and either a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) or a protease inhibitor (PI)3. Current World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines are similar, recommending a three drug regimen of two NRTIs and an NNRTI4. The preferred NRTIs in pregnancy are zidovudine and lamivudine. Use of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor and preferred drug in non-pregnant adults5, has been increasing in pregnancy6 despite its recommendation as an alternative drug in pregnancy due to concerns about potential adverse effects on the infant.

Human data on perinatal exposure to tenofovir include small case series, retrospective datasets, and prospective data from the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry and from the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS) network. In a small cohort study, Nurutdinova did not find any congenital malformations or growth abnormalities in 14 babies followed to 12 months who were exposed to tenofovir15. In a study by Eastwood, TDF exposed pregnancies were associated with efficacious viral suppression and lower risk for cesarean delivery for HIV viremia compared to those not exposed to TDF, with no increased risk for adverse neonatal outcome, including no difference in birth weight, preterm birth, or neonatal morbidity16. Among prospective cases reported to the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry, there was no overall increase in birth defects among infants exposed to tenofovir (n=1092) in the first trimester compared to later exposure (n=782), and compared to baseline population risk17, 18. Pharmacokinetics studies demonstrate about 60% placental transfer of tenofovir19.

Long-term follow-up data on the effect of tenofovir on neonatal and infant growth are sparse and conflicting. Analysis from the Safety Monitoring for ART Toxicity (SMARTT) study of the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study reported that children born to women who had received TDF as part of their HAART regimen during pregnancy were more likely to have lower length-for age and head-circumference-for-age z-scores at 1 year6, despite no observed difference in growth measurements at birth. A single case report suggested fetal growth restriction with exposure20. This is in contrast to the Development of AntiRetroviral Therapy in Africa (DART) trial, which in a subgroup analysis showed no effect of intrauterine tenofovir exposure on growth outcomes at birth through infancy21. Overall, the literature is limited in scope on neonatal and infant growth outcomes after tenofovir exposure in utero. In short, the question on whether maternal use of TDF in pregnancy has adverse effects on infant growth remains unsolved. After initial reports from the SMARTT study suggested impaired infant growth (not confirmed in the final analysis)6, we began our study on a similar population. We hypothesized that maternal use of TDF during pregnancy would predict impaired growth during infancy. Our primary objective was to evaluate the impact of in utero tenofovir exposures on growth during infancy by determining if tenofovir exposure during pregnancy is an independent predictor of birth weight and infant weight at 6 months of age, representing a delayed effect on infant growth. This is an important question to examine: with the increasing use of TDF in pregnancy despite limited safety data in the literature, large studies like ours are desperately needed to either confirm the safety profile in pregnancy or illuminate safety concerns which may temper its use.

METHODS

Study population

The study population included women enrolled in the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) protocol 1025, a prospective observational cohort study designed to assess the use and safety of antiretrovirals in HIV infected pregnant women and their infants. Approximately 37% of P1025 participants overall and 45% of TDF-exposed infants were also co-enrolled in the SMARTT study6. Beginning in October 2002, HIV-infected pregnant women were enrolled if they were at least 13 years old and between 14 weeks’ gestation and 14 days postpartum. Since December 2007, enrollment was allowed as early as 8 weeks’ gestation. Institutional review boards approved the protocol at all 56 clinical sites located in the US and Puerto Rico, and written informed consent was obtained from those enrolled. The population eligible for this study consisted of all liveborn singleton infants with an estimated date of confinement on or before September 15, 2011. Infants found to be HIV-infected were excluded. For this analysis, only the first eligible pregnancy with a livebirth > 23 weeks gestation was included for women enrolled for more than one pregnancy. This was done to avoid the need to account for correlation between multiple infants born to the same mother and simplify the analysis and interpretation of data. Only infants whose mothers used a combination ARV regimen (triple ARV regimen or greater) during pregnancy were included. Birth weight and infant weight at 6 months (+/− 1 month) were utilized for this analysis.

ARV classification and covariates

Sociodemographic characteristics, obstetrical history, substance use information, maternal antiretroviral use, and laboratory testing results were collected through medical chart abstraction or self-administered questionnaires. Potential covariates of interest included maternal viral load, CD4+ lymphocyte count, and CDC class at delivery, pre-gestational and gestational diabetes and hypertension, smoking during pregnancy, body mass index (BMI) closest to delivery, age, race, ethnicity, education, and year of delivery.

Outcomes of interest

Infant birth weight was defined in four different ways: absolute weight (continuous); gestational age- and sex-adjusted weight z-score (continuous); gestational age- and sex-adjusted weight z-score less than 5th percentile (< −1.645), and small for gestational age (SGA: gestational age- and sex-adjusted weight z-score < 10th percentile). The Olsen growth curves22 were used to calculate the z-score for all the infants (preterm and term) per completed gestational age and sex. Due to the absence of growth curves at 42 weeks of gestation, the CDC standards for the full term infants were used for the infants born at 42 weeks.

Infant weight at 6 months of age was defined in three different ways: absolute weight (continuous); age- and sex-adjusted weight z-score (continuous); and age- and sex-adjusted weight z-score less than 5th percentile (< −1.645), chosen because we felt this would be a clinically significant measure of weight at 6 months. The CDC growth charts were employed to calculate the z-score for term infants at their exact age at measurement (gestational age ≥ 37 weeks)23. For preterm infants (gestational age < 37 weeks), the exact age at the weight measurement was adjusted by subtracting the difference between 40 weeks and the gestational age at birth. The CDC growth standards were then applied to calculate the z-score based on the adjusted age. For weight at both birth and 6-months of age, several outcome definitions were chosen in an attempt to detect any signal that maternal TDF use in pregnancy would have toxic effects on infant growth.

Exposure

Maternal TDF use during pregnancy was defined in three ways: any TDF use during pregnancy; duration of TDF use during pregnancy (no use vs. < 4 weeks vs. 4-12 weeks vs. > 12 weeks of use); and the earliest trimester in which TDF was used during pregnancy (no use vs. 1st trimester vs. 2nd trimester vs. 3rd trimester). The categories for TDF duration were chosen a priori based on clinical experience on what constituted short, medium, and prolonged exposure to TDF.

Statistical analysis

Multivariable regression models were built to evaluate whether maternal TDF use predicted infant weight measurements (general linear model for continuous weight outcomes and logistic regression model for binary weight outcomes), independent of potential covariates. The potential covariates were identified separately for each outcome from bivariable analyses with a p-value < 0.10. For each weight outcome, a separate regression model was fit including each of the three TDF exposures and the same set of potential covariates. Other covariates included in any of the multivariable regression models: Birth Weight: race, ethnicity, mode of delivery, parity, last CD4 count during pregnancy, last RNA during pregnancy, last CDC classification during pregnancy, maternal obesity, pre-gestational diabetes, gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, use of antihypertensive medication during pregnancy, use of diabetes medication during pregnancy, preeclampsia, smoking during pregnancy; Weight at 6-months of age: race, ethnicity, education, mode of delivery, preeclampsia. SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used to conduct all statistical analyses, and two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

STUDY POPULATION

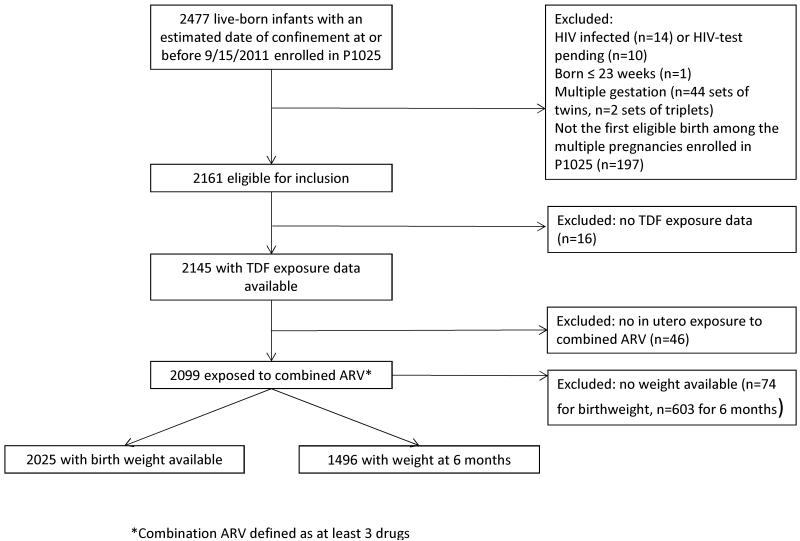

As of October 1, 2011, 2477 live-born infants with estimated date of confinement at or before September 15, 2011 enrolled in the P1025 study. After excluding infants who were HIV-infected (n=14), had HIV tests that were pending (n=10), were born at or before 23 weeks’ gestation (n=1), or not from a singleton birth (n=44 sets of twins; n=2 sets of triplets), the remaining 2358 infants were further reduced to only include the infants from their mothers’ first enrollments on study for a total of 2161 eligible infants in this analysis. Of the 2145 infants for whom maternal TDF use data were available, 2099 were exposed to a combined ARV regimen during pregnancy. The analyses were performed on the 2025 infants with birth weight available and 1496 infants with weight at 6 months of age available. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram

DEMOGRAPHICS, GROWTH AND TDF EXPOSURE

Of 2025 infants with birth weight data available, 630 (31%) were exposed to tenofovir (Table 1). The median duration of TDF exposure among those exposed was 22.9 weeks. Compared to women unexposed to TDF, women exposed to TDF in pregnancy were more likely to be on a cARV regimen containing a PI (91% vs. 79%, p<0.001), more often had CDC classification C (18% vs. 8%, p<0.001), lower last CD4+ counts (CD4 < 200 copies/mm3: 15% vs. 8%, p<0.001) and higher last RNA (RNA>400 copies/ml: 19% vs. 15%, p=0.03) prior to delivery, and were older (age at delivery ≥ 35 years: 21% vs. 15%, p<0.001), but were otherwise similar. For infants exposed to tenofovir, 66% were exposed in the first trimester and 74% were exposed for at least 12 weeks duration (Table 2). Of the 98 and 225 infants with gestational age and sex adjusted birth weight z-scores <5th percentile and <10th percentile respectively, approximately 30% were exposed to TDF in utero (Table 2). Other characteristics of the study population are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Distribution of Baseline Maternal Characteristics by TDF Exposure, Among Infants who Had Weight Measurement at Birth and Exposed to Combined ARV Regimen in Utero (N=2025) *.

| TDF Exposure |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total (N=2025) |

Unexposed (N=1395) |

Exposed (N=630) |

P-value |

| Black race | 1,224 (65%) | 850 (65%) | 374 (63%) | 0.36 |

| Hispanic | 623 (31%) | 446 (32%) | 177 (28%) | 0.08 |

| Highest education level completed < High School | 767 (38%) | 531 (38%) | 236 (38%) | 0.80 |

| Had at least one prior birth (>20 weeks) | 1,406 (69°%) | 975 (70%) | 431 (69%) | 0.54 |

| Mode of delivery: Cesarean | 1,065 (53%) | 726 (52%) | 339 (54%) | 0.45 |

| Maternal obesity (BMI > 40) | 230 (15%) | 166 (15%) | 64 (13%) | 0.23 |

| ARV regimen | ||||

| Pl-containing | 1,676 (83%) | 1,102 (79%) | 574 (91%) | < 0.001 |

| NNRTI-containing (No PI) | 145 (7%) | 115 (8%) | 30 (5%) | |

| NRTI only | 204 (10%) | 178 (13%) | 26 (4%) | |

| Last maternal CDC classification during pregnancy: | ||||

| Category C | 216 (11%) | 104 (8%) | 112 (18%) | <0.001 |

| Last maternal CD4 (cells/mm3) during pregnancy | <0.001 | |||

| ≥ 350 | 1,406 (71%) | 1,019 (75%) | 387 (62%) | |

| 200 – 349 | 375 (19%) | 236 (17%) | 139 (22%) | |

| < 200 | 206 (10%) | 112 (8%) | 94 (15%) | |

| Last maternal RNA during pregnancy > 400 (copies/mL) |

326 (16%) | 208 (15%) | 118 (19%) | 0.03 |

| Maternal age at delivery ≥ 35 years | 334 (16%) | 204 (15%) | 130 (21%) | <0.001 |

| Pre-Gestational diabetes | 33 (2%) | 25 (2%) | 8 (1%) | 0.39 |

| Gestational diabetes | 91 (4%) | 58 (4%) | 33 (5%) | 0.28 |

| Any diabetes medication use during pregnancy | 49 (2%) | 36 (3%) | 13 (2%) | 0.48 |

| Chronic hypertension | 130 (6%) | 90 (6%) | 40 (6%) | 0.93 |

| Gestational hypertension | 46 (2%) | 35 (3%) | 11 (2%) | 0.29 |

| Any antihypertensive medication use during pregnancy |

64 (3%) | 46 (3%) | 18 (3%) | 0.60 |

| Pre-eclampsia | 94 (5%) | 62 (4%) | 32 (5%) | 0.53 |

| Ever smoked cigarettes during pregnancy | 310 (22°%) | 218 (23%) | 92 (21%) | 0.49 |

The distributions of the baseline maternal characteristics among the 1496 infants who had 6-month weight measurements were similar.

Subjects with missing data were excluded from the calculations: TDF Exposed: race (39), ethnicity (4), education

(1), parity (1), mode of delivery (1), obesity (137), CDC classification (11), last CD4 during pregnancy (10), last RNA during pregnancy (8), smoked cigarettes during pregnancy (191); TDF Unexposed: race (96), ethnicity (8), education (2), mode of delivery (1), obesity (309), CDC classification (16), last CD4 during pregnancy (28), last RNA during pregnancy (24), smoked cigarettes during pregnancy (431).

Table 2. Distribution of Maternal TDF Use in Pregnancy among the Infant Study Population by Weight at Birth (N=2025) and 6-months of Age (N=1496).

| Characteristics | Birth weight | Weight at 6 months of age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=2025) |

Age and sex adjusted z- score <5% (N=98) |

Age and sex adjusted z- score <10% (N=225) |

Total (N=1496) |

Age and sex adjusted z- score <5% (N=61) |

|

| TDF use during pregnancy | |||||

| Unexposed | 1,395 (69%) | 69 (70%) | 153 (68%) | 1,039 (69%) | 37 (61%) |

| Exposed | 630 (31%) | 29 (30%) | 72 (32%) | 457 (31%) | 24 (39%) |

| Trimester of 1st reported TDF exposure |

|||||

| 1st Trimester | 418 (21%) | 20 (20%) | 45 (20%) | 302 (20%) | 12 (20%) |

| 2nd or 3rd Trimester | 212 (10%) | 9 (9%) | 27 (12%) | 155 (10%) | 12 (20%) |

| Unexposed | 1,395 (69%) | 69 (70%) | 153 (68%) | 1,039 (69%) | 37 (61%) |

| Duration of TDF exposure during pregnancy |

|||||

| < 4 weeks | 40 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (2%) | 28 (2%) | 2 (3%) |

| 4 - 12 weeks | 124 (6%) | 5 (5%) | 11 (5%) | 101 (7%) | 6 (10%) |

| >12 weeks | 466 (23%) | 22 (22%) | 57 (25%) | 328 (22%) | 16 (26%) |

| Unexposed | 1,395 (69%) | 69 (70%) | 153 (68%) | 1,039 (69%) | 37 (61%) |

The adjusted associations of maternal TDF use with birth weight are presented in Table 3 (weight in kg and z-scores) and in Table 4 (low birth weight). No significant associations were observed between TDF exposures (any TDF exposure, trimester of the 1st reported TDF use, and duration of TDF exposure) and the weight outcomes of interest. As expected, women who had a higher last CD4 count during pregnancy (CD4 < 200 vs. ≥ 350 cells/mm3), women defined as obese (BMI>40) during pregnancy, those who had at least one previous birth with greater than 20 weeks gestation, and those who had a pre-gestational or gestational diabetes diagnosis, were more likely to deliver a heavier baby as measured by one or more of the weight outcomes of interest compared to women who did not have these characteristics. In contrast, black women, women who used antihypertensive medications during pregnancy, women who had a pre-eclampsia diagnosis and those who smoked cigarettes during pregnancy were more likely to deliver a baby with lower weight as measured by one or more of the weight outcomes of interest compared to women who did not have these characteristics.

Table 3. Adjusted Mean Weight and Weight Z-score by Maternal TDF Use during Pregnancy, among Infants Exposed in Utero to a Combined ARV Regimen.

| TDF Exposure | Birth Weight (n = 2025) | Weight at 6-months of Age (n = 1496) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Weight (kg) | Gestational age- and sex- adjusted Z-score |

Weight (kg) | Age- and sex- adjusted Z-score | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (SE) | P-value* | Mean (SE) | P-value* | Mean (SE) | P-value* | Mean (SE) | P-value* | |

| Any TDF exposure | ||||||||

| Unexposed ** | 2.77 (0.06) | Ref | 0.14 (0.11) | Ref | 7.59 (0.08) | Ref | 0.26 (0.05) | Ref |

| Exposed | 2.75 (0.06) | 0.64 | 0.14 (0.11) | 0.90 | 7.64 (0.09) | 0.52 | 0.29 (0.07) | 0.61 |

|

| ||||||||

| Trimester of 1st reported exposure |

||||||||

| 1st trimester | 2.75 (0.06) | 0.53 | 0.15 (0.12) | 0.90 | 7.67 (0.10) | 0.31 | 0.34 (0.08) | 0.29 |

| 2nd/3rd trimester | 2.77 (0.07) | 0.97 | 0.11 (0.13) | 0.66 | 7.57 (0.12) | 0.80 | 0.19 (0.10) | 0.55 |

|

| ||||||||

| Duration of exposure | ||||||||

| < 4 weeks | 2.75 (0.11) | 0.84 | 0.14 (0.19) | 0.97 | 7.64 (0.24) | 0.83 | 0.17 (0.23) | 0.71 |

| 4 – 12 weeks | 2.79 (0.08) | 0.66 | 0.24 (0.14) | 0.32 | 7.64 (0.14) | 0.72 | 0.31 (0.13) | 0.66 |

| > 12 weeks | 2.74 (0.06) | 0.48 | 0.11 (0.12) | 0.57 | 7.64 (0.09) | 0.58 | 0.30 (0.08) | 0.62 |

P-values from multivariate regression model comparing the adjusted means.

Reference group for the comparisons of adjusted means between TDF exposures.

Other covariates included in any of the multivariate regression models: Birth Weight: race, ethnicity, mode of delivery, parity, last CD4 count during pregnancy, last RNA during pregnancy, last CDC classification during pregnancy, maternal obesity, pre-gestational diabetes, gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension use of antihypertensive medication during pregnancy, use of diabetes medication during pregnancy, preeclampsia, smoke during pregnancy; Weight at 6-months of Age: race, ethnicity, education, mode of delivery, preeclampsia.

Table 4. Adjusted Odds Ratio (OR) for Under-weight Outcomes by TDF Exposure during Pregnancy, among Infants Exposed in Utero to a Combined ARV Regimen.

| TDF Exposure | Birth Weight (n = 2025) | 6-month Weight (n = 1496) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Gestational age- and sex- adjusted Z-score < 5th percentile |

Gestational age- and sex- adjusted Z-score < 10th percentile |

Age- and sex- adjusted Z-score < 5th percentile |

||||

|

| ||||||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value* | OR (95% CI) | P-value* | OR (95% CI) | P-value* | |

| Any TDF exposure | ||||||

| 0.65 | 1.40 | |||||

| Exposed | 0.89 0.65 (0.52, 1.48) |

1.09 (0.77,1.52) 0.64 |

(0.81,2.36) 0.22 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Trimester of 1st reported exposure |

||||||

| 0.73 | 0.97 | 0.92 | ||||

| 1st trimester | 0.90 (0.49, 1.59) |

1.01 (0.67,1.49) |

1.04 (0.50,1.99) |

|||

| 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.04 | ||||

| 2nd/3rd trimester | 0.85 (0.34, 1.86) |

1.26 (0.74,2.07) |

2.06 (1.01,3.95) |

|||

| Duration of exposure | ||||||

| 0.95 | 0.80 | 0.28 | ||||

| < 4 weeks | 1.06 (0.16, 3.90) |

1.15 (0.33,3.10) |

2.27 (0.36,8.10) |

|||

| 0.99 | 0.53 | 0.51 | ||||

| 4 – 12 weeks | 1.00 (0.33, 2.44) |

0.79 (0.34,1.59) |

1.38 (0.47,3.30) |

|||

| 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.34 | ||||

| > 12 weeks | 0.84 (0.46, 1.48) |

1.16 (0.79,1.66) |

1.34 (0.71,2.40) |

|||

P-values from multivariate regression model for adjusted odds ratios. TDF-unexposed was the reference group for all comparisons.

Other covariates included in any of the multivariate regression models: Birth Weight: race, ethnicity, parity, last CD4 count during pregnancy, maternal obesity, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, smoke during pregnancy; Weight at 6-months of Age: ethnicity

Of 1496 infants with weight data available at 6 months of age, 457 (31%) were exposed to tenofovir (Table 2). The median duration of TDF exposure among those exposed was 21.3 weeks. For infants exposed to TDF in this group, 66% were exposed in the first trimester and 72% were exposed for >12 weeks duration. Of the 61 infants with age and sex adjusted 6 month weight z-scores <5th percentile, 38% were exposed to TDF in utero. The group of women with infants followed for 6 months was not different than the entire group with infant birth weight available with respect to measured demographic and clinical information.

The multivariable associations of TDF exposures with weight at 6 months are presented in Table 3 and Table 4. In comparison to mothers with no TDF exposure, maternal initiation of TDF during the 2nd/3rd trimester was predictive of low infant weight at 6-months of age based on age- and sex-adjusted weight z-score < 5th percentile. No other significant associations were observed between TDF exposures (any TDF exposure, trimester of the 1st reported TDF use, and duration of TDF exposure) and other weight measures (absolute weight, age- and sex-adjusted weight Z-score). Women who completed at least a high school education were more likely to have a heavier baby in terms of absolute weight and age- and sex-adjusted weight z-score at 6-months of age; babies whose mother had a pre-eclampsia diagnosis were more likely to have a lower mean absolute weight at 6-months of age than those whose mother didn’t have a pre-eclampsia diagnosis. Hispanic women were less likely to have a baby with age- and sex-adjusted weight z-score below the 5th percentile at 6-months of age, compared to Non-Hispanic women.

PRETERM BIRTH

No significant associations were observed between the TDF exposures and the preterm birth outcome. Of the 2099 infants exposed in utero to a combined ARV regimen, there were no differences in preterm birth among infants whose mothers were exposed to a TDF regimen compared to those who weren’t (117 (18%) versus 232 (16%), p=0.26). Non-obese women, women on anti-hypertensive therapy during pregnancy, women with preeclampsia, and women with a last reported CD4+ lymphocyte count <200 cells/mm3 during pregnancy were more like to deliver a baby prematurely.

DISCUSSION

With the increasing use of TDF by HIV-infected pregnant women, studies examining the safety profile of this drug in exposed neonates are crucial. In this large cohort of infants born to HIV-infected women receiving combination ARV regimens during pregnancy, in utero exposure to tenofovir does not appear to be associated with either infant birth weight or infant growth through six months of age. While there was a marginal association with being underweight at 6 months of age in women who initiated TDF in the second or third trimester, there was no association between duration of maternal TDF use and 6-month weight outcomes. In addition, no association was found with absolute weight or overall age and sex adjusted z-score. As expected, women who were obese, diabetic, parous and without hypertensive diseases of pregnancy tended to have larger babies, both at birth and at 6 months of age.

While we feel it may not be clinically significant, the isolated finding of lower age and sex adjusted weight z-score of <5th % at 6 months of age in infants of women who initiated TDF in the second or third trimester should not be completely overlooked. There are several studies in humans that suggest a delay in effect from ARV exposure not occurring until several months to years after exposure. For instance, febrile seizures were significantly more common in ARV-exposed compared to ARV-unexposed HIV-exposed infants; this effect did not appear until 6-12 months of age24. In the Women and Infants Transmission Study (WITS), the significant difference in CD8+ cell counts by ARV exposure did not appear until 6-24 months25. In the Surveillance Monitoring for ART Toxicities (SMARTT) trial, data at 1 year but not at birth demonstrated lower mean length-for-age and head-circumference-for-age z-scores associated with maternal TDF use6. More encouraging are results from the Development of AntiRetroviral Therapy in Africa (DART) trial21, which recently reported no evidence that TDF effects growth of infants up to 2 years of age, in a cohort of 226 live births. The clinical relevance and underlying biologic mechanisms of this finding in our study are uncertain. Long term studies are needed to determine whether this short term effect on growth has any long lasting impact in childhood or adult life.

Our study has several strengths. We had a large sample size, with large (31%) proportion of infants having tenofovir exposure. In addition, we were able to examine growth in several different ways (absolute weight, underweight, and small for gestational age). We were also able to examine tenofovir exposure by several different measures, to determine if exposure in the first trimester had an effect or if cumulative dose of tenofovir had an effect. Neither appears to have affected fetal or infant growth.

There are, however, some limitations to our study. Tenofovir is eliminated by the kidneys. Renal toxicity with Fanconi syndrome and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus has been reported in children7 and adults 8, 9, 10, 11 exposed to TDF. There have also been reports of bone toxicity in infant rhesus macaques12, 13. Due to the rarity of these outcomes in infants and reporting bias, our study was unable to examine the effects of tenofovir exposure on either the kidneys or bones. It is reassuring that long-term safety data in rhesus macaques shows the renal toxicity to be dose related, with no increased risk of congenital anomalies and good long-term safety data for the offspring14. However, examining the renal effects of tenofovir exposure in utero is an unmet research need.

Like any cohort study, there is potential for selection bias in the non-random allocation of women to TDF as part of their multi-agent HAART. In addition, more women exposed to TDF were on a PI containing HAART regimen than those not exposed to TDF, which may lead to confounding in results. Approximately 26% of the infants with birth weight available do not have available 6 month weight values to study. In addition, we were not able to examine growth beyond 6 months. Another limitation is that we only examined growth as a function of weight and not length or head circumference. We recognize this is an important limitation, especially in light of findings from the SMARTT study demonstrating adverse effects on length-for age and head-circumference-for-age z-scores at 1 year6, despite no observed difference in growth measurements at birth. We also do not have data on maternal adherence to drug therapy, and thus true fetal exposure. Current guidelines from the Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission assign TDF as an alternate agent (not first line) for the treatment of acute HIV infection in pregnant women while it is considered first line treatment in other groups. The need for long-term data on TDF is vital given the rising use in a pregnant population. Long-term growth and developmental outcomes are still needed in children exposed to tenofovir in future large cohorts. There are many challenges to obtaining long-term safety data on drugs used to treat HIV in pregnancy. This population has many socioeconomic and cultural barriers to seeking and maintaining care, there is difficulty in monitoring drug adherence, and this group is often exposed to multiple drug regimens. While we acknowledge that 45% of TDF-exposed infants were also co-enrolled in the SMARTT study6, we feel our study still significantly contributes to the literature on this population given the sparse literature on the topic, the challenges to obtaining this information, and the growing use of TDF in clinical obstetric practice. The results of our study present an overall reassuring picture for both fetal growth as well as neonatal growth as reflected by weight in neonates exposed to TDF in pregnancy. Future studies should be designed to focus on rare neonatal outcomes (fracture, neutropenia, etc.) as well as long-term delayed effects on infant growth.

Acknowledgements

P1025 Team Acknowledgement: Ruth Tuomala, M.D., Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Elizabeth Smith, M.D., National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Division of AIDS, Pediatric Medicine Branch, Bethesda, Maryland, USA; KaSaundra M. Oden, M.H.S., International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group, Silver Spring, Maryland, USA; Deborah Kacanek, Sc.D., Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Erin Leister, M.S., Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; David E. Shapiro, Ph.D., Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Emily A. Barr, C.P.N.P., C.N.M., M.S.N, University of Colorado Denver, The Children’s Hospital, Denver, Colorado, USA; Diane W. Wara, M.D., University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA; Arlene Bardeguez, M.D., M.P.H., F.A.C.O.G., University of Medicine & Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, New Jersey, USA; Sandra K. Burchett, M.D., M.Sc., Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Jenny Guiterrez, M.D., Bronx-Lebanon Hospital, Bronx, New York, USA; Kathleen Malee, Ph.D., Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Alice M. Stek, M.D., Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA; Patricia Tanjutco, M.D., Washington Hospital Center, Washington, D.C., USA; Yvonne Bryson, MD, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA; Michael T. Basar, B.S., Frontier Science & Technology Research Foundation, Inc., Amherst, New York, USA; Adriane Hernandez, M.A., Frontier Science & Technology Research Foundation, Inc., Amherst, New York, USA; Amy Jennings, B.S., Frontier Science & Technology Research Foundation, Inc., Amherst, New York, USA; Tim R. Cressey, Ph.D., B.Sc., Program for HIV Prevention & Treatment, Chang Mai, Thailand; Jennifer Bryant, M.P.A., Westat, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

Obstetrics Site Support: 2802 NJ Medical School CRS (Arlene D. Bardeguez, MD, MPH; Linda Bettica, RN; Charmane Calilap-Bernardo, RN); 3601 UCLA-Los Angeles/Brazil AIDS Consortium (LABAC) CRS; 3801 Texas Children’s Hospital CRS; 4001 Chicago Children’s CRS; 4101 Columbia IMPAACT CRS (Alice Higgins, RN; Gina Silva, RN; Sreedhar Gaddipati, MD); 4201 University of Miami Pediatric/Perinatal HIV/AIDS CRS (Salih Yasin, MD, Charles Mitchell, MD, Sylvia Lo Wong, M.D,, Patricia Bryan, RN); 4601 UCSD Maternal, Child, and Adolescent HIV CRS (Stephen A. Spector, MD; Andrew Hull, MD; Mary Caffery, RN, MSN; Jean Manning, RN, BSN); 4701 DUMC Pediatric CRS (Elizabeth Livingston, MD; Margaret Donnelly, PA; Joan Wilson, RN; Julia Giner, RN); 5003 Metropolitan Hospital NICHD CRS; 5009 Children’s Hospital of Boston NICHD CRS (Nancy Karthas, RN, MS, CPNP; Lisa Tucker, BFA; Arlene Buck, RN; Catherine Kneut, RN, MS, CPNP); 5011 Boston Medical Center Pediatric HIV Program NICHD CRS; 5012 NYU NY NICHD CRS (Sandra Deygoo, MS; Aditya Kaul, MD; Maryam Minter, RN; Siham Akleh, RN; Supported in part by grant UL1 TR000038 from the National Center for the Advancement of Translational Science (NCATS), National Institutes of Health); 5013 Jacobi Medical Center Bronx NICHD CRS; 5015 Children’s National Medical Center Washington DC NICHD CRS; 5017 Seattle Children’s Hospital CRS (Amanda Robson; Jane Hitti, MD; Corry Venema-Weiss, CNM; Anna Klastorin, MSW); 5018 University of South Florida, Tampa NICHD CRS (Karen L. Bruder, MD; Gail Lewis, RN; Denise Casey, RN); 5023 Washington Hospital Center NICHD CRS (Sara Parker, MD; Rachel Scott, MD; Patricia Tanjutco, MD; Vanessa Emmanuel, BA); 5031 San Juan City Hospital PR NICHD CRS (Antonio Mimoso, MD; Rodrigo Diaz, MD; Elvia Perez; Olga Pereira); 5040 SUNY Stony Brook NICHD CRS (Jennifer Griffin, NP; Paul Ogburn, MD); 5041 Children’s Hospital of Michigan NICHD CRS; 5044 Howard University Washington DC NICHD CRS; 5045 Harbor UCLA Medical Center NICHD CRS; 5048 University of Southern California, LA NICHD CRS (Alice Stek, MD; Francoise Kramer, MD; LaShonda Spencer, MD; Andrea Kovacs, MD); 5051 University of Florida College of Medicine, Jacksonville NICHD CRS (Mobeen Rathore, MD; Isaac Delke, MD; Geri Thomas, RN; Barbara Millwood, RN); 5052 University of Colorado, Denver NICHD CRS (Alisa Katai, MHA; Tara Kennedy, FNP-BC; Kay Kinzie, FNP-BC; Jenna Wallace, MSW; Supported by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000154); 5055 South Florida CDC, Ft Lauderdale NICHD CRS; 5083 Rush University Cook County Hospital, Chicago NICHD CRS (Julie Schmidt, MD; Helen Cejtin, MD; Maureen McNichols, RN, MSN, CCRC; Judith Senka, RN); 5091 University of California, San Francisco NICHD CRS (Deborah Cohan, MD; This publication was supported by NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH); 5092 Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore NCHD CRS (Jean Anderson, MD; Eileen Sheridan-Malone, RN); 5093 Miller Children’s Hospital Long Beach, CA NICHD CRS (Chritina Tolentino-Balbridge, RN; Janielle Jackson-Alvarez, RN; David Michalik, DO; Jagmohan S. Batra, MD); 5094 University of Maryland Baltimore NICHD CRS (Douglas Watson, MD; Maria Johnson, DDS; Corinda Hilyard); 5095 Tulane University, New Orleans NICHD CRS (Robert Maupin, MD; Chi Dola, MD; Yvette Luster, RN; Sheila Bradford, RN); 5096 University of Alabama Birmingham NICHD CRS (Alan Tita, MD; Micky Parks, CRNP; Sharan Robbins, BA); 6501 St. Jude/UTHSC CRS (Edwin Thorpe, Jr, MD; Katherine Knapp, MD; Pamela Finnie, MSN; Nina Sublette, RN, PhD); 6601 University of Puerto Rico Pediatric HIV/AIDS Research Program CRS (Carmen D Zorrilla, MD; Vivian Tamayo-Agrait, MD); 6701 The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia IMPAACT CRS; 6901 Bronx-Lebanon Hospital IMPAACT CRS (Rodney Wright, MD); 7301 WNE Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS CRS (Sharon Cormier, RN; Katherine Luzuriaga, MD; Supported by CTSA Grant Number: 8UL1TR000161).

Overall support for the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [U01 AI068632], the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) [AI068632]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Analysis Center at Harvard School of Public Health, under the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases cooperative agreement #5 U01 AI41110 with the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) and #1 U01 AI068616 with the IMPAACT Group. Support of the sites was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the NICHD International and Domestic Pediatric and Maternal HIV Clinical Trials Network funded by NICHD (contract number N01-DK-9-001/HHSN267200800001C).

Sources of Funding: Overall support for the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [U01 AI068632], the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) [AI068632]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Analysis Center at Harvard School of Public Health, under the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases cooperative agreement #5 U01 AI41110 with the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) and #1 U01 AI068616 with the IMPAACT Group. Support of the sites was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the NICHD International and Domestic Pediatric and Maternal HIV Clinical Trials Network funded by NICHD (contract number N01-DK-9-001/HHSN267200800001C).

Footnotes

Presented at the International Aids Society 2012 Meeting, Washington, D.C., July 2012

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

Disclaimers: none

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Feb 1;40(3):458–465. doi: 10.1086/427287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper ER, Charurat M, Mofenson L, et al. Combination antiretroviral strategies for the treatment of pregnant HIV-1-infected women and prevention of perinatal HIV-1 transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002 Apr 15;29(5):484–494. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200204150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Accessed 4/10/13];Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1-Infected Women for Maternal Health and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. 2012 Jul 31; http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/PerinatalGL.pdf.

- 4.World Health Organization [Accessed 3/08/13];ANTIRETROVIRAL DRUGS FOR TREATING PREGNANT WOMEN AND PREVENTING HIV INFECTION IN INFANTS: Recommendations for a public health approach-2010 version. 2010. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599818_eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- 5.Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-Infected adults and adolescents. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines. [PubMed]

- 6.Siberry GK, Williams PL, Mendez H, et al. Safety of tenofovir use during pregnancy: early growth outcomes in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. AIDS. 2012 Jun 1;26(9):1151–1159. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328352d135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hussain S, Khayat A, Tolaymat A, Rathore MH. Nephrotoxicity in a child with perinatal HIV on tenofovir, didanosine and lopinavir/ritonavir. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006 Jul;21(7):1034–1036. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karras A, Lafaurie M, Furco A, et al. Tenofovir-related nephrotoxicity in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: three cases of renal failure, Fanconi syndrome, and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Clin Infect Dis. 2003 Apr 15;36(8):1070–1073. doi: 10.1086/368314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peyriere H, Reynes J, Rouanet I, et al. Renal tubular dysfunction associated with tenofovir therapy: report of 7 cases. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004 Mar 1;35(3):269–273. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200403010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coca S, Perazella MA. Rapid communication: acute renal failure associated with tenofovir: evidence of drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Am J Med Sci. 2002 Dec;324(6):342–344. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200212000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rifkin BS, Perazella MA. Tenofovir-associated nephrotoxicity: Fanconi syndrome and renal failure. Am J Med. 2004 Aug 15;117(4):282–284. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarantal AF, Castillo A, Ekert JE, Bischofberger N, Martin RB. Fetal and maternal outcome after administration of tenofovir to gravid rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002 Mar 1;29(3):207–220. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200203010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarantal AF, Marthas ML, Shaw JP, Cundy K, Bischofberger N. Administration of 9-[2-(R)-(phosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine (PMPA) to gravid and infant rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta): safety and efficacy studies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999 Apr 1;20(4):323–333. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199904010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Rompay KK, Durand-Gasselin L, Brignolo LL, et al. Chronic administration of tenofovir to rhesus macaques from infancy through adulthood and pregnancy: summary of pharmacokinetics and biological and virological effects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008 Sep;52(9):3144–3160. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00350-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nurutdinova D, Onen NF, Hayes E, Mondy K, Overton ET. Adverse effects of tenofovir use in HIV-infected pregnant women and their infants. Ann Pharmacother. 2008 Nov;42(11):1581–1585. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eastwood KPK, Melvin A, Venema-Weiss C, Hitti J. effect of tenofovir on viral suppression during pregnancy in HIV-1 infected women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;2010:S233. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlevari MZS, Olmscheid B. Use of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (TDF) and Emtricitabine (FTC) in Pregnancy: Findings from the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry (APR) Infection. 2009;37:96. [Google Scholar]

- 18. [Accessed 10.10.2012];Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry. 2012 http://www.APRegistry.com.

- 19.Hirt D, Urien S, Ekouevi DK, et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Tenofovir in HIV-1-Infected Pregnant Women and Their Neonates (ANRS 12109) Nature. 2009;85(2):182–189. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinai E, Hosokawa S, Gomibuchi H, Gatanaga H, Kikuchi Y, Oka S. Blunted fetal growth by tenofovir in late pregnancy. AIDS. 2012 Oct 23;26(16):2119–2120. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328358ccaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibb DM, Kizito H, Russell EC, et al. Pregnancy and infant outcomes among HIV-infected women taking long-term ART with and without tenofovir in the DART trial. PLoS medicine. 2012;9(5):e1001217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsen IE, Groveman SA, Lawson ML, Clark RH, Zemel BS. New intrauterine growth curves based on United States data. Pediatrics. 2010 Feb;125(2):e214–224. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Advance data. 2000 Jun 8;(314):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landreau-Mascaro A, Barret B, Mayaux MJ, Tardieu M, Blanche S. Risk of early febrile seizure with perinatal exposure to nucleoside analogues. Lancet. 2002 Feb 16;359(9306):583–584. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07717-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pacheco SE, McIntosh K, Lu M, et al. Effect of perinatal antiretroviral drug exposure on hematologic values in HIV-uninfected children: An analysis of the women and infants transmission study. J Infect Dis. 2006 Oct 15;194(8):1089–1097. doi: 10.1086/507645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]