Abstract

The autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxias (also known as the SCAs) are a diverse and clinically heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by degeneration and dysfunction of the cerebellum and its associated pathways. Clinical and diagnostic evaluation can be challenging due to phenotypic overlap amongst numerous acquired, genetic, and idiopathic etiologies, and a stratified and systematic approach is essential. Molecular etiologies include DNA repeat expansions (both polyglutamine and non-coding repeats), ion-channel dysfunction, and disorders of signal transduction. Prompt recognition of acquired conditions or comorbidities is essential as treatment options for the genetic ataxias are currently limited. Recent advances in the field include the identification of additional genes causing dominant genetic ataxia, a better understanding of cellular pathogenesis in several disorders, the generation of new disease models which may stimulate development of new therapies, and the use of new DNA sequencing technologies, including whole exome sequencing, to improve diagnosis.

Keywords: ataxia, cerebellum, spinocerebellar, SCA, autosomal dominant

INTRODUCTION

Definition

The spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) are a heterogeneous group of degenerative disorders with symptoms caused by dysfunction of the cerebellum and brainstem, along with their associated pathways and connections, and with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance.

Symptoms and Clinical Course

All patients exhibit cerebellar ataxia (limb, trunk, and/or gait)

Additional symptoms are variable and disease specific including extrapyramidal features, long tract signs, peripheral neuropathy, and, in some cases, cognitive impairment and seizures (see Table 1).

Clinical course: The polyglutamine ataxias SCA1, SCA2, and SCA3 are progressive disorders with death resulting primarily from brain stem dysfunction [1]. In one series, median survival was in the mid-50s, 21–25 years following symptom onset [2]. The other causes of SCA tend to have a more pure cerebellar dysfunction leading to significant disability but with normal lifespan.

Table 1.

Summary of genes, mutations, and clinical features of autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxias.

| Name | Locus/ Gene | Protein/Mutationa | Normal functionb | Yearc | Pathologyd | Symptoms/ Signse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCA 1 | 6p23/ A TXN 1 | Ataxin 1 CAG repeats 41–81 (normal 25–36) |

Gene transcription and RNA splicing | 1994 | Inferior olivary nuclei Pontine nuclei Purkinje cells |

Pyramidal signs Amyotrophy Extrapyramidal signs Ophthalmoparesis |

| SCA 2 | 12q24/ A TXN 2 | Ataxin 2 CAG repeats 35–59 (normal 15–24) |

RNA processing | 1996 | Basis pontis Inferior olivary nuclei Purkinje cells |

Slow saccades Extrapyramidal signs Dementia (rarely) Ophthalmoplegia Peripheral neuropathy Pyramidal signs |

| SCA 3 (Machado– Joseph Disease/ MJD) | 14q24.3-q31/ ATXN 3 | Ataxin 3 CAG repeats 62–82 (normal 13–36) |

Debuiqutinating enzyme involved in protein quality control | 1994 | Anterior horn cells Clarke’s columns Dentate nuclei Dorsal root ganglia Pontine nuclei Purkinje cells Spinocerebellar tracts Substantia nigra Subthalamic nuclei |

Pyramidal signs Amyotrophy Exophthalmos Extrapyramidal signs Ophthalmoparesis |

| SCA4 | 16q22.1/ distinct from SCA31 | Unknown | Unknown | -- | Unknown |

Sensory axonal neuropathy Pyramidal signs |

| SCA5 | 11q13/ SPTBN2 | β III Spectrin | Scaffolding protein important for glutamate signaling | 2006 | Unknown |

Pure cerebellar ataxia (late onset) Pyramidal signs (early onset) |

| SCA6 | 19p13.2/ CACNA1A | Cav2.1 CAG repeats 21–30 (normal 6–17) |

Calcium channel important for regulating Purkinje neuron excitability | 1997 | Purkinje cells | Pure cerebellar ataxia Late onset, usually >50 years |

| SCA7 | 3p21.1-p12 | Ataxin 7 CAG repeats 38–130 (normal 7–17) |

Gene transcription | 1997 | Cone-rod dystrophy Dentate nuclei Inferior olivary nuclei Pontine neurons Purkinje cells Retinal ganglion cells |

Pigmentary macular degeneration Ophthalmoplegia Pyramidal signs |

| SCA8 | 13q21.33/ ATXN8OS ATXN8 | Toxic RNA/ CAG repeats | Unknown | 1999 | Purkinje cells Substantia nigra |

Pyramidal signs Diminished vibratory sense Spastic and ataxic dysarthria |

| SCA9 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | -- | Unknown | Central demyelination (one patient) Extrapyramidal signs Ophthalmoplegia Posterior column loss Pyramidal tract signs |

| SCA10 | 22q13.31/ ATXN10 | Intronic ATTCT repeats | Involved in neuron survival, neuron differentiation, and neuritogenesis | 2000 | Unknown |

Seizures Cognitive/neuropsychiatric impairment Polyneuropathy Pyramidal signs |

| SCA11 | 15q15.2/ TTBK2 | Tau tubulin kinase-2 | Serine-threonine kinase that putatively phosphorylates tau and tubulin proteins Regulates the genesis of the primary cilium | 2007 | Unknown | Pure cerebellar ataxia |

| SCA12 | 5q32/ PPP2R2B | Protein phosphatase PP2A CAG repeats in 5’-UTR 51–78 (normal 7–32) |

Serine-threonine phosphatase implicated in the negative control of cell growth and division | 1999 | Unknown | Upper extremity tremor Mild or absent gait ataxia Hyperreflexia |

| SCA13 | 19q13.3–13.4/ KCNC3 | Kv3.3 | Potassium channel involved in regulating Purkinje neuron excitability | 2006 | Unknown |

Intellectual disability (in French pedigree) Pure cerebellar ataxia (in Filipino pedigree) |

| SCA14 | 19q13.4/P RKCG | Protein Kinase C Gamma | Neuronal serine/threonine protein kinase activated by calcium and diacylglycerol | 2003 | Unknown |

Pure cerebellar ataxia Rarely chorea and cognitive deficits |

| SCA15/SCA16 | 3p26.1/ ITPR1 | Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor | Intracellular calcium channel involved in regulating neuronal excitability | 2007 | Unknown |

Pure cerebellar ataxia Rare tremor or cognitive impairment |

| SCA17/ Huntington disease like 4 (HDL4) | 6q27/ TBP | TATA box-binding protein CAG repeats 46–63 (normal 25–42) |

Gene transcription | 2001 | Neuronal inclusion bodies in brain Purkinje cells Reduction in brain weight |

Chorea Dementia Extrapyramidal features Hyperreflexia Psychiatric symptoms |

| SCA18 Sensorimotor Neuropathy with Ataxia/ SMNA | 7q22-q32 | Unknown | Unknown | -- | Unknown |

Posterior column loss Amyotrophy Early onset, usually <20 years Hyporeflexia |

| SCA19/SCA22 | 1p13.3/ KCND3 | Kv4.3 | Potassium channel involved in regulating neuronal excitability | 2012 | Unknown |

Pure cerebellar ataxia Cognitive impairment Myoclonus Postural tremor |

| SCA20 | 11p11.2-q13.3/gene duplication | Unknown | Unknown | -- | Dentate nucleus calcification |

Spasmodic dysphonia or spasmodic coughing Palatal tremor |

| SCA21 | 7p21.3-p15.1 | Unknown | Unknown | -- | Unknown | Akinesia Cognitive impairment Dysgraphia Early onset Hyporeflexia Postural tremor Resting tremor Rigidity |

| SCA23 | 20p13/ PDYN | Prodynorphin | Processed to form secreted opioid peptides that serve as ligands for the kappa- type opioid receptor | 2010 | Cerebellar vermis Cerebellopontine tracts Dentate nuclei Demyelination of posterior and lateral columns (1 patient) Inferior olivary nuclei |

Late onset, usually >50 years Decreased vibratory sense |

| SCA25 | 2p21-p15 | Unknown | Unknown | -- | Unknown | Areflexia Peripheral sensory neuropathy |

| SCA26 | 19p13.3 | Unknown | Unknown | -- | Unknown | Pure cerebellar ataxia |

| SCA27 | 13q34/ FGF14 | Fibroblast growth factor 14 | Interacts with voltage-gated sodium channels and regulates Purkinje neuron excitability | 2003 | Unknown |

Orofacial dyskinesias Cognitive impairment Tremor |

| SCA28 | 18p11.22-q11.2/ AFG3L2 | ATPase family gene 3-like 2 | Mitochondrial protein synthesis | 2010 | Unknown |

Early onset, usually <20 years Hyperreflexia Ophthalmoparesis Ptosis |

| SCA29 | 3p26 | Unknown | Unknown | -- | Unknown |

Congenital Nonprogressive |

| SCA30 | 4q34.3-q35.1 | Unknown | Unknown | -- | Unknown | Late onset, usually >50 years Pure cerebellar ataxia |

| SCA31 | 16q22/ BEAN1 and TK2 | Brain expressed, associated with NEDD4 Thymidine Kinase2 TGGAA repeat in intron shared by both genes |

Unknown | 2009 | Purkinje cells |

Pure cerebellar ataxia Late onset, usually >50 years Sensorineural hearing loss |

| SCA35 | 20p13/ TGM6 | Transglutaminase 6 | Post-translational modifications of glutamine residues | 2010 | Unknown | Pyramidal signs Psuedobulbar palsy |

| SCA36 | 20p13/ NOP56 | Nucleolar protein 56 Intronic GGCCTG repeat | Pre-mRNA processing | 2011 | Dentate nuclei Hypoglossal nucleus Motor neurons Purkinje cells |

Lower motor neuron involvement Tongue atrophy |

| DRPLA (Dentato- Rubral Pallidoluysian Atrophy) | 12p13.31/ ATN1 | Atrophin 1 CAG repeats 49–75 (normal 7–23) |

Transcriptional co- regulator | 1994 | Cerebellar white matter Dentate nuclei Globus pallidus Red nucleus Subthalamic nucleus |

Myoclonic epilepsy Choreoathetosis Dementia |

Mutation refer to point mutations in the respective genes, unless otherwise specified.

The normal function of all proteins has not been fully established.

Year refers to initial year of publication of the identified gene.

Pathology refers to loss of neurons in the indicated regions.

Not all patients will have the symptoms/signs that are mentioned. Bold typeface refers to symptoms either characteristic or unique to the particular SCA and thus helpful to diagnosis.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Ataxia is defined as a disturbance of balance and coordination occurring in the absence of muscle weakness, and can arise from dysfunction of the cerebellum, the vestibular system, or of proprioception, alone or in combination (see Box 1) [3, 4]. The cerebellum plays a critical role in this process through the integration of multimodal sensory data with motor output predictions to yield smooth well-timed movement [5].

Box 1. Physical Examination Findings in a Patient with Ataxia*.

-

Cerebellar Examination

Gaze-evoked nystagmus

Abnormal eye movements (ocular dysmetria, impaired smooth pursuit)

Dysarthria (scanning)

Limb Dysmetria (finger-to-nose, finger chase, heel-shin testing)

Dysdiadochokinesis

Loss of check on removal of extremity resistance

Truncal ataxia and/or head titubation

Wide-based unsteady gait (“drunk” gait)

Inability to tandem walk

-

Vestibular Examination

Spontaneous nystagmus

Past-pointing

Abnormal head thrust or Dix-Hallpike testing

-

Sensory Examination

Reduced proprioception

Reduced vibration sense

Abnormal Romberg test

*Not comprehensive. Not all patients will exhibit all features.

Physical Examination

The focus of thephysical examination should be on eliciting signs specific for cerebellar dysfunction and extracerebellar findings.

Disruption of cerebellar function manifests as impairment in coordinated muscle activity, most often observed clinically as dysarthria, dysphagia, ocular dysmetria, altered visual pursuit, direction-changing nystagmus, limb dysmetria, gait disturbance, and/or falls [3, 4].

In slowly progressive cases, gait impairment is often seen early and is frequently associated with a sense of imbalance or feelings of generalized leg weakness.

Exacerbation may occur when walking on uneven surfaces or under conditions of reduced sensory input, such as in low lighting. Stance often widens for additional stabilization and patients may require support to walk, especially on turning. When indoors, the practice of navigating from support to support (e.g., across items of furniture) can become a common means of ambulation.

Depending upon the etiology of the ataxia, associated clinical features may be present and, in some cases, could be helpful to establishing the diagnosis, particularly in the case of genetic ataxias (see Table 1).

GENETICS

Despite their similarity in clinical symptoms, an array of diverse genetic causes underlie the SCAs. The genes accounting for autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia are summarized in Table 1.

MOLECULAR PATHOGENESIS

Although distinct genes account for the over 30 etiologies of dominant ataxia, groups of disorders may be recognized with shared molecular mechanisms of disease. These include the polyglutamine ataxias, ataxias associated with ion-channel dysfunction, mutations in signal transduction molecules, and disease associated with non-coding repeats.

1. Polyglutamine ataxias

These include SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA7, SCA12, SCA17, and DRPLA, where expansion within a glutamine encoding CAG repeat accounts for disease. An additional disorder, SCA8, likely arises from the combined effects of a non-coding CTG repeat expansion and the generation of a pure polyglutamine protein from the corresponding CAG repeat on the opposite strand [6].

The exact mechanism for how a polyglutamine protein causes ataxia is not understood. Potential mechanisms [7] include:

Protein misfolding resulting in altered function

Formation of toxic oligomeric complexes

Transcriptional dysregulation

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Impaired axonal transport

Aberrant neuronal signaling including excitotoxicity

Cellular protein homeostasis impairment

RNA toxicity

2. Ion-channel mutations/dysfunction

Either direct ion-channel mutations or secondary ion-channel dysfunction has been implicated in the pathogenesis of SCA5, SCA6, SCA13, SCA15/16, SCA19/22, and SCA27 [8].

SCA5: Mutations in the structural protein, beta-3 spectrin result in SCA5. In a mouse model of disease Purkinje neurons exhibit reduced spontaneous firing, smaller sodium currents, and dysregulation of glutamatergic neurotransmission [9].

SCA6: Results from a modest polyglutamine expansion in the C-terminus of a neuronal calcium channel, Cav2.1. The exact mechanism for disease pathogenesis may include calcium channel dysfunction and/or polyglutamine protein associated toxicity [10].

SCA13: Mutations in KCNC3, the gene encoding the Kv3.3 potassium channel, either suppress currents or alter channel gating in a dominant-negative manner [11]. The SCA13 mutations in Kv3.3 also reduce neuronal excitability in a zebrafish model of disease [12].

SCA15/16: Mutations in the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor, an intracellular ligand gated calcium channel, underlie this disorder. Decreased modulation of Purkinje neuron intrinsic firing by excitatory synaptic input is described in a mouse model of disease [13].

SCA19/22: Loss of function mutations in Kv4.3 cause ataxia [14, 15]. The physiologic basis for this recently identified cause of SCA is unclear.

SCA27: Although SCA27 does not result from an ion-channel mutation, the causative FGF14 mutations likely result in perturbed expression of voltage-gated sodium channels in cerebellar neurons [16].

3. Signal transduction

Although alterations in cellular signal transduction likely play a role in the majority of ataxias, mutations in signal transduction molecules are the direct cause of disease in SCA11, SCA12, SCA14 and SCA23.

SCA11: Results from loss of function mutations in TTBK2, a casein kinase 1 family member. Recent work has implicated this kinase as a dedicated regulator of the initiation of ciliogenesis [17].

SCA12: Results from a CAG repeat expansion in the 5’-untranslated region of protein phosphatase, PP2A. The mechanism for disease pathogenesis likely shares common features with the other non-coding repeat disorders.

SCA14: Results from mutations in a serine-threonine family kinase, a protein kinase C isoform, that is highly enriched in Purkinje neurons. In a mouse model of disease, mutant PKCgamma reduced long term depression at parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses and increased slow EPSC amplitude [18].

SCA23: Mutations in PDYN, the precursor protein for the opioid neuropeptides, α-neoendorphin, and dynorphins A and B (Dyn A and B) cause SCA23. Cellular models of disease suggest that alterations in Dyn A activities and/or impairment of secretory pathways by mutant PDYN may lead to glutamate neurotoxicity, underlying Purkinje cell degeneration and ataxia [19].

4. Non coding repeats/ RNA toxicity

This is the likely mechanism of pathogenesis in SCA8, SCA10, SCA31 and SCA36. The putative mechanism of disease includes [20]

Transcriptional alterations and the generation of antisense transcripts

Sequestration of mRNA-associated protein complexes that lead to aberrant mRNA splicing and processing

Alterations in cellular processes, including activation of abnormal signaling cascades and failure of protein quality control pathways

GENOMICS

Anticipation: The polyglutamine ataxias show the phenomenon of anticipation, where disease onset is seen earlier in successive generations. This occurs due to germ line CAG repeat instability leading to additional repeat expansion. SCA7, for example, has marked anticipation of approximately 20 years/generation [21].

Association with other neurological disorders: Intermediate-length polyQ expansions (27–33 glutamines) in ATXN2 are significantly associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [22]. Ataxin 2 acts as a modifier of TDP-43 toxicity, a protein thought to be critical for ALS pathogenesis, in animal and cellular models. ATXN2 and TDP-43 associate in a complex that depends on RNA.

DISEASE MODELS

The autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxias disorders have been studied in cultured cells, animal models, and, most recently, in human inducible pluripotent stem cell derived neurons.

Cultured cells: Mutations have been studied in both cultured neurons and non-neuronal cell lines.

Animal models: Various animal models of these disorders exist and include mouse, zebrafish, and fly models of disease that are summarized in Table 2.

Inducible pluripotent stem cell derived neurons: Patient-derived cells lines have been generated for SCA3 [23].

Table 2.

Animal models of SCA.

| Name | Type of modela | Phenotype | Pathology | Selected Therapy Trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCA1 | Transgenic-(Purkinje neuron specific), 82Q [s1] | Motor incoordination | Shrinkage and marked loss of Purkinje neurons | shRNA [s3] |

| Knock-in, 154Q [s2] | Cognitive impairment Kyphosis Motor incoordination Premature death Weight loss |

Mild loss of Purkinje neurons | Lithium [s4] Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) [s5] |

|

|

| ||||

| SCA2 | Transgenic 58Q and 127Q (Purkinje neuron specific)[s6] | Motor incoordination | Shrinkage and mild loss of Purkinje neurons | Dantrolene [s7] SK channel activator [s8] |

|

| ||||

| SCA3 (Machado– Joseph Disease/ MJD) | Transgenic (many models including 79Q[s9], 148Q [s10], 71Q [s11], 94Q [s12], 77Q [s13]) | Motor incoordination Premature death | Variable shrinkage and mild neuronal loss | Sodium butyrate [s19] |

| Yeast Artificial Chromosome Transgenic [s14–16] |

Motor incoordination | Mild and late loss of brain stem and cerebellar neurons | Dantrolene [s15] | |

| Rat model-lentiviral injection and overexpression of mutant ataxin-3 in the striatum or substantia nigra [s17] | Circling behavior following unilateral substantia nigra injection | Fluorojade positive neurons and cell shrinkage | shRNA [s20] | |

| Fly eye [s18] | Loss of ommatidia | |||

|

| ||||

| SCA5 | Knock-out [s21] | Motor incoordination | Shrinkage and mild loss of Purkinje neurons | |

|

| ||||

| SCA6 | Knock-in 84Q [s22] | Motor incoordination | Very mild Purkinje neuron loss | |

|

| ||||

| SCA7 | Transgenic [s23] | Motor incoordination | Mild Purkinje neuron loss | |

|

| ||||

| SCA8 | Klh1 deletion [s24] | Motor incoordination | Purkinje neuron shrinkage | |

|

| ||||

| SCA10 | Transgenic 500 repeats in 3’ UTR [s25] | Motor incoordination Seizure susceptibility |

Loss of CA3 hippocampal neurons | |

|

| ||||

| SCA13 | Knockout [s26] | Motor incoordination | No neuronal loss | |

| Zebrafish R420H human mutation [s27] | No neuronal loss | |||

|

| ||||

| SCA14 | Transgenic H501Y [s28] | Abnormal clasping | Altered Purkinje neuron morphology | |

|

| ||||

| SCA15/SCA16 | Knockout [s29] | Motor incoordination Seizures | No neuronal loss | |

|

| ||||

| SCA17/ Huntington disease like 4 (HDL4) | Transgenic 109Q [s30] | Motor incoordination | Loss of Purkinje neurons | |

|

| ||||

| SCA27 | Knockout [s31] | Cognitive deficits Motor incoordination |

No neuronal loss | |

|

| ||||

| DRPLA | Transgenic variable repeat length 76Q- 129Q [s32] | Cognitive deficits Motor incoordination Premature death |

Purkinje neuron shrinkage and progressive brain atrophy | |

Refers to mouse models unless otherwise specified.

Burright, E.N., et al., SCA1 transgenic mice: a model for neurodegeneration caused by an expanded CAG trinucleotide repeat. Cell, 1995. 82(6): p. 937–48.

Watase, K., et al., A long CAG repeat in the mouse Sca1 locus replicates SCA1 features and reveals the impact of protein solubility on selective neurodegeneration. Neuron, 2002. 34(6): p. 905–19.

Xia, H., et al., RNAi suppresses polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration in a model of spinocerebellar ataxia. Nat Med, 2004. 10(8): p. 816–20.

Watase, K., et al., Lithium therapy improves neurological function and hippocampal dendritic arborization in a spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 mouse model. PLoS Med, 2007. 4(5): p. e182.

Cvetanovic, M., et al., Vascular endothelial growth factor ameliorates the ataxic phenotype in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Nat Med, 2011. 17(11): p. 1445–7.

Hansen, S.T., et al., Changes in Purkinje cell firing and gene expression precede behavioral pathology in a mouse model of SCA2. Hum Mol Genet, 2012.

Liu, J., et al., Deranged calcium signaling and neurodegeneration in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. J Neurosci, 2009. 29(29): p. 9148–62.

Kasumu, A.W., et al., Selective positive modulator of calcium-activated potassium channels exerts beneficial effects in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Chem Biol, 2012. 19(10): p. 1340–53.

Chou, A.H., et al., Polyglutamine-expanded ataxin-3 causes cerebellar dysfunction of SCA3 transgenic mice by inducing transcriptional dysregulation. Neurobiol Dis, 2008. 31(1): p. 89–101.

Boy, J., et al., A transgenic mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 resembling late disease onset and gender-specific instability of CAG repeats. Neurobiol Dis, 2010. 37(2): p. 284–93.

Goti, D., et al., A mutant ataxin-3 putative-cleavage fragment in brains of Machado-Joseph disease patients and transgenic mice is cytotoxic above a critical concentration. J Neurosci, 2004. 24(45): p. 10266–79.

Silva-Fernandes, A., et al., Motor uncoordination and neuropathology in a transgenic mouse model of Machado-Joseph disease lacking intranuclear inclusions and ataxin-3 cleavage products. Neurobiol Dis, 2010. 40(1): p. 163–76.

Boy, J., et al., Reversibility of symptoms in a conditional mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3.Hum Mol Genet, 2009. 18(22): p. 4282–95.

Cemal, C.K., et al., YAC transgenic mice carrying pathological alleles of the MJD1 locus exhibit a mild and slowly progressive cerebellar deficit. Hum Mol Genet, 2002. 11(9): p. 1075–94.

Chen, X., et al., Deranged calcium signaling and neurodegeneration in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. J Neurosci, 2008. 28(48): p. 12713–24.

Shakkottai, V.G., et al., Early changes in cerebellar physiology accompany motor dysfunction in the polyglutamine disease spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. J Neurosci, 2011. 31(36): p. 13002–14.

Alves, S., et al., Striatal and nigral pathology in a lentiviral rat model of Machado-Joseph disease. Hum Mol Genet, 2008. 17(14): p. 2071–83.

. Warrick, J.M., et al., Expanded polyglutamine protein forms nuclear inclusions and causes neural degeneration in Drosophila. Cell, 1998. 93(6): p. 939–49.

Chou, A.H., et al., HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate reverses transcriptional downregulation and ameliorates ataxic symptoms in a transgenic mouse model of SCA3. Neurobiol Dis, 2011. 41(2): p. 481–8.

Alves, S., et al., Silencing ataxin-3 mitigates degeneration in a rat model of Machado-Joseph disease: no role for wild-type ataxin-3? Hum Mol Genet, 2010. 19(12): p. 2380–94.

Perkins, E.M., et al., Loss of beta-III spectrin leads to Purkinje cell dysfunction recapitulating the behavior and neuropathology of spinocerebellar ataxia type 5 in humans. J Neurosci, 2010. 30(14): p. 4857–67.

Watase, K., et al., Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 knockin mice develop a progressive neuronal dysfunction with age-dependent accumulation of mutant CaV2.1 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2008. 105(33): p. 11987–92.

Furrer, S.A., et al., Spinocerebellar ataxia type 7 cerebellar disease requires the coordinated action of mutant ataxin-7 in neurons and glia, and displays non-cell-autonomous bergmann glia degeneration. J Neurosci, 2011. 31(45): p. 16269–78.

He, Y., et al., Targeted deletion of a single Sca8 ataxia locus allele in mice causes abnormal gait, progressive loss of motor coordination, and Purkinje cell dendritic deficits. J Neurosci, 2006. 26(39): p. 9975–82.

White, M., et al., Transgenic mice with SCA10 pentanucleotide repeats show motor phenotype and susceptibility to seizure: a toxic RNA gain-of-function model. J Neurosci Res, 2012. 90(3): p. 706–14.

Hurlock, E.C., A. McMahon, and R.H. Joho, Purkinje-cell-restricted restoration of Kv3.3 function restores complex spikes and rescues motor coordination in Kcnc3 mutants. J Neurosci, 2008. 28(18): p. 4640–8.

Issa, F.A., et al., Spinocerebellar ataxia type 13 mutant potassium channel alters neuronal excitability and causes locomotor deficits in zebrafish. J Neurosci, 2011. 31(18): p. 6831–41.

Zhang, Y., et al., Loss of Purkinje cells in the PKCgamma H101Y transgenic mouse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2009. 378(3): p. 524–8.

Matsumoto, M., et al., Ataxia and epileptic seizures in mice lacking type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Nature, 1996. 379(6561): p. 168–71.

Chang, Y.C., et al., Neuroprotective effects of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor in a novel transgenic mouse model of SCA17. J Neurochem, 2011. 118(2): p. 288–303.

Wang, Q., et al., Ataxia and paroxysmal dyskinesia in mice lacking axonally transported FGF14.Neuron, 2002. 35(1): p. 25–38.

Sato, T., et al., Severe neurological phenotypes of Q129 DRPLA transgenic mice serendipitously created by en masse expansion of CAG repeats in Q76 DRPLA mice. Hum Mol Genet, 2009. 18(4): p. 723–36.

EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT

The evaluation and management of a patient with spinocerebellar ataxia involves the rapid identification of any treatable etiologies and, once those are excluded, an efficient and systematic search for a genetic cause, coupled with symptomatic therapies to minimize functional loss.

Clinical Examination and Diagnostic Testing

A detailed neurological assessment with careful attention to the examination of coordination, sensation (especially proprioception), and vestibular function is essential to the diagnosis of an ataxia (see Box 1) [3, 4].

Examination must include a careful evaluation of the movements of the eyes for errors in targeting, tracking, dysmetria, or nystagmus.

Speech may be dysarthric, typically with a scanning quality.

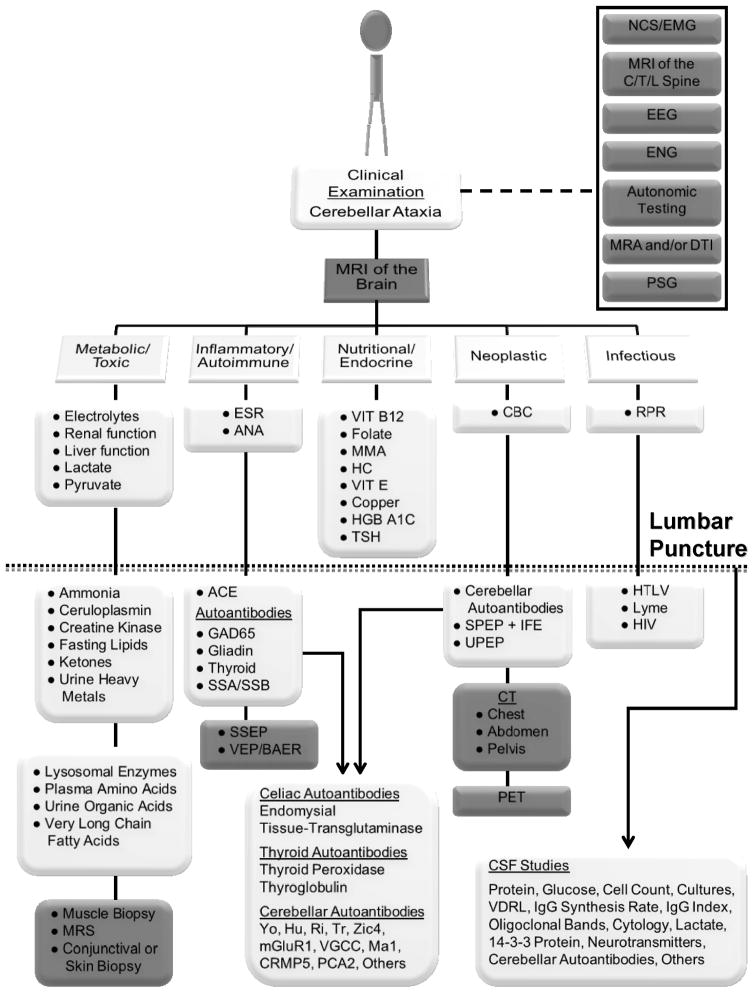

Ataxia must be defined as either sporadic or familial. Sporadic cases typically favor an acquired process, which should be prioritized for initial testing (see Figure 1) as this has the greatest potential for effective treatment.

In sporadic cases, once acquired conditions are excluded, genetic and idiopathic disorders represent the next line of investigation.

A familial history of ataxia necessitates earlier consideration of genetic etiologies, however acquired processes must still be adequately explored (see Figure 1).

The tempo of disease onset and progression can be very helpful in the prioritization of acquired etiologies for subsequent testing (see Table 3).

Idiopathic disorders, of which multiple system atrophy is the most likely to present initially with ataxia,[3, 4, 24] remain diagnoses of exclusion and should not be made unless a reasonable exploration of acquired and genetic etiologies has first been pursued.

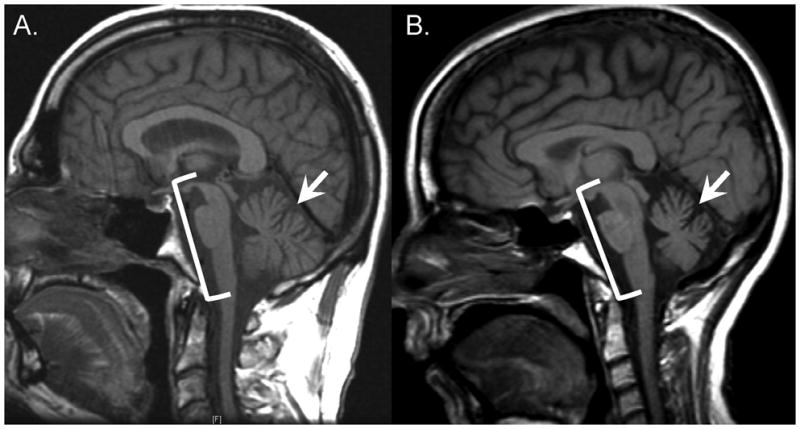

For cerebellar ataxia, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain is the initial diagnostic test of choice [3, 4, 25, 26]. Imaging is critical to assess for the presence of cerebellar atrophy (see Figure 2) as well as for the presence of any identifiable evidence of structural or vascular damage (e.g., stroke, tumor, etc.) [27] and/or other lesions or associated neurodegeneration which could be diagnostically useful (e.g., white matter hyperintensities, atrophy of the brainstem or spinal cord, loss of transverse pontine fibers, etc.) [4, 25, 26].

Subsequent laboratory and diagnostic studies for acquired causes of cerebellar ataxia should be performed in a stepwise fashion and tailored to the presentation of the individual patient (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diagnostic evaluation of an acquired cerebellar ataxia.

All patients with clinically identified cerebellar ataxia should have an MRI of the brain performed to assess for masses, vascular lesions/anomalies, traumatic injury, and/or structural problems in addition to evidence of neurodegeneration and/or white matter changes. Additional diagnostic studies (gray boxes) should be performed as warranted based upon the clinical examination (dashed line). If the MRI does not reveal the cause, then laboratory tests (white boxes) should be performed systematically as indicated. Studies are listed under the heading of the class of disorders they most often identify. Note that some tests could identify disorders in more than one class. In a complete evaluation, a patient should receive, at a minimum, all studies listed above the dotted line. Items listed below the dotted line are chosen for more in-depth evaluation of specific etiologies and not all patients may require all studies. The dotted line represents the threshold for performing a lumbar puncture in a patient undergoing initial workup. Suggested cerebral spinal fluid studies are indicated (arrow). Specific cerebellar (paraneoplastic), celiac, and thyroid autoantibodies are also shown (arrow). Note that there are additional rare acquired causes of cerebellar ataxia which are not listed in this figure.

Abbreviations: ACE = angiotensin converting enzyme, ANA = antinuclear antibodies, BAER = brainstem auditory evoked response, CBC = complete blood count, C/T/L = cervical, thoracic, and/or lumbar, CSF = cerebral spinal fluid, CT = computed tomography, DTI = diffusion tensor imaging, EEG = electroencephalogram, EMG = electromyogram, ENG = electronystagmogram, ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate, GAD = glutamic acid decarboxylase, HC = homocysteine, HGB = hemoglobin, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, HTLV = human T-lymphotropic virus, IFE = immunofixation electrophoresis, MMA = methylmalonic acid, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, MRA = magnetic resonance angiography, MRS = magnetic resonance spectroscopy, NCS = nerve conduction study, PET = positron emission tomography, PSG = polysomnogram, RPR = rapid plasma reagin, SSA/SSB = Sjögren’s syndrome antigen, SPEP = serum protein electrophoresis, SSEP = somatosensory evoked potentials, TSH = thyroid stimulating hormone, UPEP = urine protein electrophoresis, VDRL = venereal disease research laboratory test, VEP = visual evoked potential, VIT = vitamin.

Original figure previously published[4] © Cambridge University Press 2011. Reprinted with permission.

Table 3.

Using the tempo of disease onset and progression to aid diagnosis.

| Symptom Onset/Progression | Etiologies to Consider* |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Episodic (Minutes to Hours) | Genetic |

| Inflammatory | |

| Toxic | |

| Vascular | |

|

| |

| Acute (Hours to Days) | Infection |

| Metabolic | |

| Toxic | |

| Trauma | |

| Vascular | |

|

| |

| Subacute (Weeks to Months) | Autoimmune |

| Infection | |

| Inflammatory | |

| Neoplastic | |

| Paraneoplastic | |

|

| |

| Chronic (Months to Years) | Autoimmune |

| Degenerative | |

| Genetic | |

| Inflammatory | |

| Metabolic | |

| Neoplastic | |

| Paraneoplastic | |

|

| |

| Static (Years to Decades) | Congenital |

| Cerebellar Injury (any source) | |

Not a comprehensive list.

Figure 2. MRI Findings in Spinocerebellar Ataxia.

Sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging is shown for a patient with A) Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3 (SCA3) and B) Multiple System Atrophy (MSA). Cerebellar atrophy (arrow) and brainstem atrophy (bracket) are noted. Note the similarity in imaging characteristics between these patients as this is common among the different ataxia etiologies (i.e., acquired, hereditary, and idiopathic).

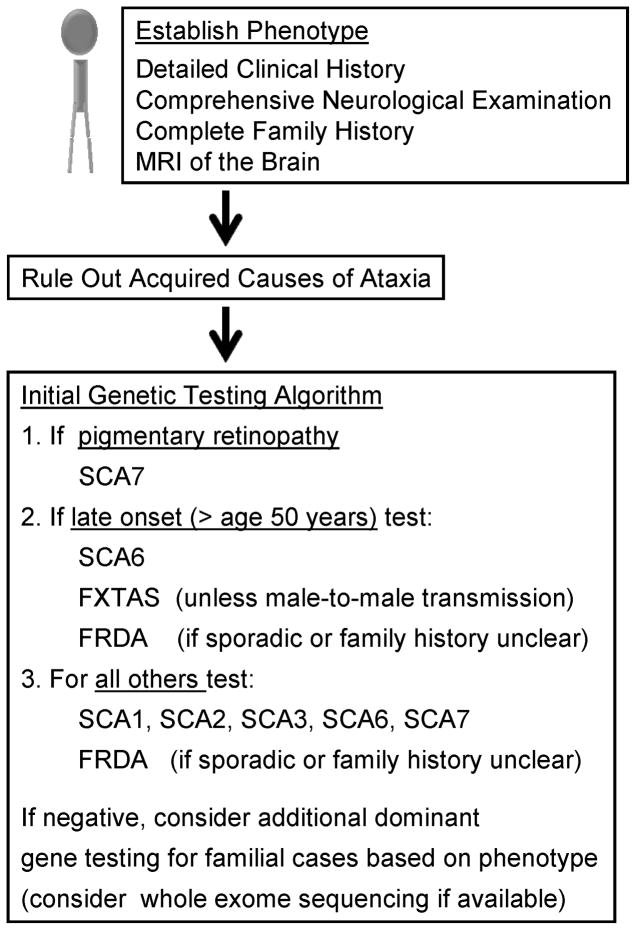

Genetic testing

Careful attention must be paid to clinical phenotype. In general, the autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) show phenotypic heterogeneity,[1, 3, 4] however certain clinical features can aid in the prioritization of disorders for genetic testing (e.g., seizures in SCA10, parkinsonism in SCA3, or dementia in SCA17; see Table 1).

Ethnicity and geographic origin should also be considered, as several SCAs are more common in specific populations (e.g., SCA3 in Brazil or DRPLA in Japan) [1, 4, 28]. Worldwide, the most common SCA is SCA3, which together with SCA1, SCA2, SCA6, and SCA7 comprise 50% of all dominant ataxias [1, 28, 29]. In late onset cases (onset greater than age 50), SCA6 and Fragile X tremor/ataxia syndrome are most frequent [1, 3, 4].

Genetic testing should be performed in a stratified fashion based on phenotype (see Figure 3). In sporadic cases, it may be reasonable to screen for the most common autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxias, however widespread screening should be avoided as the diagnostic yield is disproportionally low relative to the cost of testing [1, 4, 30].

Autosomal recessive disorders, particularly late-onset variants of Friedreich ataxia, become a consideration in sporadic patients from small families,[31, 32] complicating diagnostic testing (see Figure 3).

Newer genome-wide methods of sequencing technology may alleviate a majority of testing problems and become a staple for future testing algorithms (see Box 2, Figure 3)[33, 34].

Figure 3. Diagnostic evaluation of a genetic cerebellar ataxia.

Abbreviations: FRDA = Friedreich ataxia, FXTAS = Fragile X tremor/ataxia syndrome, SCA = spinocerebellar ataxia.

Box 2. Clinical Exome Sequencing.

Recent advances in DNA sequencing technology have made it possible to rapidly and cheaply sequence large amounts of DNA, including whole genomes [38, 39]. Sequencing of the 1–2% of the genome expressed as protein (known as the exome) can examine the approximately 20,000 genes in the human genome simultaneously to localize protein-altering sequence variation, and is expected to dramatically impact the evaluation of neurogenetic disease [33, 34, 39]. Although unable to detect mutations caused by repeat expansion, noncoding variation, or large deletions/duplications [34], with regard to cerebellar ataxia, there are already key examples illustrating the use of this technology in the identification of new ataxia genes, [40, 41] the detection of novel mutations, [42, 43] and the diagnosis of patients with clinically heterogeneous spinocerebellar phenotypes [44]. Questions still remain regarding how best to bioinformatically process these large amounts of sequence information to identify pathogenic variants in individual patients, particularly those involving novel mutations and genes, but there is little doubt that this technology will see widespread clinical use in the immediate future [33, 34].

Current Management and Therapeutic Options

Many of the acquired causes of cerebellar ataxia (see Figure 1) can be treated or modified, emphasizing the need for prompt recognition to minimize damage to the cerebellum and its associated pathways [4].

Paraneoplastic and other autoimmune mediated ataxias are particularly important to consider since, if left unchecked, rapid and severe damage to the cerebellum can result and, unfortunately, current treatments are often less than fully effective [4, 35].

No cures or effective treatments yet exist for genetic or idiopathic ataxias and treatment is therefore wholly symptomatic, however, exercise therapy has been shown to be beneficial in maintaining patient function over time and should be employed for all patients [36, 37].

SUMMARY

The autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxias (the SCAs) are late onset progressive degenerative disorders that may be categorized into repeat disorders, disorders of ion-channel dysfunction, and disorders of signal transduction molecules. The identification of additional genes and the development of better cellular and animal model systems of disease pathogenesis continue to advance understanding and suggest new avenues for better diagnosis and potential intervention. Due to the considerable clinical overlap between these disorders and other acquired causes of ataxia, the evaluation of patients with cerebellar ataxia must first include an investigation into potentially treatable causes. If genetic testing is considered, it is best to take a tiered approach, with initial testing including the most common dominant genes, namely SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA7 and, in sporadic cases, Friedreich ataxia, the most common recessive cause. Management is mainly supportive, but exercise therapy has been shown to be beneficial in maintaining patient function over time.

KEY POINTS.

The SCAs or spinocerebellar ataxias are aheterogeneous group of dominantly inherited disorders, the most common of which are SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6 and SCA7, all of which result from glutamine encoding repeats in the respective genes.

The polyglutamine ataxias tend to be “ataxia-plus” disorders with extrapyramidal symptoms, long tract signs and cranial nerve dysfunction and have a poorer prognosis. In addition to polyglutamine ataxias, other molecular mechanisms for ataxia include ion-channel dysfunction, disordered signal transduction, and non-coding repeats.

Advances in DNA sequencing technologies, including whole exome sequencing, are expected to improve the diagnosis of genetic ataxias.

Animal models of disease recapitulate many of the key features of the human disease and may be good model systems to test therapies.

Current management for the SCAs is mostly supportive. However, exercise therapy has been shown to be beneficial in maintaining patient function over time

and should be employed for all patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K08NS072158 to V.G.S. and K08MH086297 to B.L.F).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Durr A. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: polyglutamine expansions and beyond. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(9):885–94. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klockgether T, et al. The natural history of degenerative ataxia: a retrospective study in 466 patients. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 4):589–600. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fogel BL, Perlman S. An approach to the patient with late-onset cerebellar ataxia. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2(11):629–35. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0319. quiz 1 p following 635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fogel BL, Perlman S. Cerebellar disorders: Balancing the approach to cerebellar ataxia. In: Gálvez-Jiménez N, Tuite PJ, editors. Uncommon Causes of Movement Disorders. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011. pp. 198–216. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manto M, et al. Consensus paper: roles of the cerebellum in motor control--the diversity of ideas on cerebellar involvement in movement. Cerebellum. 2012;11(2):457–87. doi: 10.1007/s12311-011-0331-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikeda Y, Daughters RS, Ranum LP. Bidirectional expression of the SCA8 expansion mutation: one mutation, two genes. Cerebellum. 2008;7(2):150–8. doi: 10.1007/s12311-008-0010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams AJ, Paulson HL. Polyglutamine neurodegeneration: protein misfolding revisited. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(10):521–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shakkottai VG, Paulson HL. Physiologic alterations in ataxia: channeling changes into novel therapies. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(10):1196–201. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perkins EM, et al. Loss of beta-III spectrin leads to Purkinje cell dysfunction recapitulating the behavior and neuropathology of spinocerebellar ataxia type 5 in humans. J Neurosci. 2010;30(14):4857–67. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6065-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kordasiewicz HB, Gomez CM. Molecular pathogenesis of spinocerebellar ataxia type 6. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4(2):285–94. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waters MF, et al. Mutations in voltage-gated potassium channel KCNC3 cause degenerative and developmental central nervous system phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2006;38(4):447–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Issa FA, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 13 mutant potassium channel alters neuronal excitability and causes locomotor deficits in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2011;31(18):6831–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6572-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumoto M, et al. Ataxia and epileptic seizures in mice lacking type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Nature. 1996;379(6561):168–71. doi: 10.1038/379168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Yi-chung, et al. Mutations in KCND3 cause spinocerebellar ataxia type 22. Ann Neurol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ana.23701. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duarri A, et al. Mutations in potassium channel KCND3 cause spinocerebellar ataxia type 19. Ann Neurol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ana.23700. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shakkottai VG, et al. FGF14 regulates the intrinsic excitability of cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33(1):81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goetz SC, Liem KF, Jr, Anderson KV. The spinocerebellar ataxia- associated gene tau tubulin kinase 2 controls the initiation of ciliogenesis. Cell. 2012;151(4):847–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shuvaev AN, et al. Mutant PKCgamma in spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 disrupts synapse elimination and long-term depression in Purkinje cells in vivo. J Neurosci. 2011;31(40):14324–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5530-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakalkin G, et al. Prodynorphin mutations cause the neurodegenerative disorder spinocerebellar ataxia type 23. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(5):593–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Todd PK, Paulson HL. RNA-mediated neurodegeneration in repeat expansion disorders. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(3):291–300. doi: 10.1002/ana.21948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebre AS, Brice A. Spinocerebellar ataxia 7 (SCA7) Cytogenet Genome Res. 2003;100(1–4):154–63. doi: 10.1159/000072850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elden AC, et al. Ataxin-2 intermediate-length polyglutamine expansions are associated with increased risk for ALS. Nature. 2010;466(7310):1069–75. doi: 10.1038/nature09320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch P, et al. Excitation-induced ataxin-3 aggregation in neurons from patients with Machado-Joseph disease. Nature. 2011;480(7378):543–6. doi: 10.1038/nature10671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilman S, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2008;71(9):670–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000324625.00404.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klockgether T. Sporadic ataxia with adult onset: classification and diagnostic criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(1):94–104. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Gaalen J, van de Warrenburg BP. A practical approach to late- onset cerebellar ataxia: putting the disorder with lack of order into order. Pract Neurol. 2012;12(1):14–24. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2011-000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fogel BL, Salamon N, Perlman S. Progressive spinocerebellar ataxia mimicked by a presumptive cerebellar arteriovenous malformation. European Journal of Radiology Extra. 2009;71(1):e1–e2. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schols L, et al. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: clinical features, genetics, and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(5):291–304. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00737-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finsterer J. Ataxias with autosomal, X-chromosomal or maternal inheritance. Can J Neurol Sci. 2009;36(4):409–28. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100007733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fogel BL, et al. Mutations in rare ataxia genes are uncommon causes of sporadic cerebellar ataxia. Mov Disord. 2012;27(3):442–6. doi: 10.1002/mds.24064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fogel BL. Childhood cerebellar ataxia. J Child Neurol. 2012;27(9):1138–45. doi: 10.1177/0883073812448231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fogel BL, Perlman S. Clinical features and molecular genetics of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxias. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(3):245–57. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coppola G, Geschwind DH. Genomic medicine enters the neurology clinic. Neurology. 2012;79(2):112–4. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825f06d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fogel BL, Geschwind DH. Clinical Neurogenetics. In: Daroff R, Fenichel G, Jankovic J, Mazziotta J, editors. Neurology in Clinical Practice. 6. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012. pp. 704–734. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panzer J, Dalmau J. Movement disorders in paraneoplastic and autoimmune disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24(4):346–53. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328347b307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ilg W, et al. Intensive coordinative training improves motor performance in degenerative cerebellar disease. Neurology. 2009;73(22):1823–30. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c33adf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ilg W, et al. Long-term effects of coordinative training in degenerative cerebellar disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25(13):2239–46. doi: 10.1002/mds.23222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metzker ML. Sequencing technologies - the next generation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(1):31–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bras J, Guerreiro R, Hardy J. Use of next-generation sequencing and other whole-genome strategies to dissect neurological disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(7):453–64. doi: 10.1038/nrn3271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doi H, et al. Exome Sequencing Reveals a Homozygous SYT14 Mutation in Adult-Onset, Autosomal-Recessive Spinocerebellar Ataxia with Psychomotor Retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(2):320–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang JL, et al. TGM6 identified as a novel causative gene of spinocerebellar ataxias using exome sequencing. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 12):3510–8. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dundar H, et al. Identification of a novel Twinkle mutation in a family with infantile onset spinocerebellar ataxia by whole exome sequencing. Pediatr Neurol. 2012;46(3):172–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li M, et al. Whole exome sequencing identifies a novel mutation in the transglutaminase 6 gene for spinocerebellar ataxia in a Chinese family. Clin Genet. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sailer A, et al. Exome sequencing in an SCA14 family demonstrates its utility in diagnosing heterogeneous diseases. Neurology. 2012;79(2):127–31. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825f048e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]