Abstract

The theoretical homology based structural model of Cry1Ab15 δ-endotoxin produced by Bacillus thuringiensis BtB-Hm-16 was predicted using the Cry1Aa template (resolution 2.25 Å). The Cry1Ab15 resembles the template structure by sharing a common three-domain extending conformation structure responsible for pore-forming and specificity determination. The novel structural differences found are the presence of β0 and α3, and the absence of α7b, β1a, α10a, α10b, β12, and α11a while α9 is located spatially downstream. Validation by SUPERPOSE and with the use of PROCHECK program showed folding of 98% of modeled residues in a favourable and stable orientation with a total energy Z-score of −6.56; the constructed model has an RMSD of only 1.15 Å. These increments of 3D structure information will be helpful in the design of domain swapping experiments aimed at improving toxicity and will help in elucidating the common mechanism of toxin action.

1. Introduction

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) a soil bacterium produces pertinacious toxin generally referred to as insecticidal crystal protein. This toxin belongs to a large family with target spectrum spanning insects, nematodes, flatworm, and protozoa [1]. In nature, Cry toxins are produced as crystalline protoxin (hence named Cry protein) within Bt sporangia, and after ingestion by a susceptible insect larva, these protoxins are solubilized and proteolytically cleaved into an active toxin fragment that binds to at least one of the four different types of high affinity receptors and later get inserted into the brush border epithelium. The insertion of toxin creates pores in the cell membrane that causes the leaching of the cellular electrolytes. This disruption causes cell lyses and finally larval death [2]. So far, Cry1 toxins have extensively been used in studies of insect control either as transgenic spores or as spray formulations. Where three-dimensional crystal structure of Cry1 family of protein is concerned, few of the toxins in solutions have been analysed by X-ray diffraction crystallography [3–9], and a few of them have been predicted using the homology modelling method [10–12]. All these toxins have a different toxicity spectrum; in spite of this, these proteins show a similar tertiary organization. This property impels for elucidation of three-dimensional structures of the rest of the reported Cry1 family members for possible setting down of unifying mechanisms underlying the toxicity. There are currently many templates for protein structures prediction available from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [13], and all such templates are constantly increasing in number. For three-dimensional structure prediction, modeled structure, by applying template-based modeling, has become so accurate that they can be applied for molecular replacement information in many cases. Therefore, in this paper, as an increment in a structure elucidation, the model of the Cry1Ab15 toxin is reported based on the hypothesis of structural similarity with Cry1Aa toxin [7]. This model supports existing hypotheses of receptor insertion and will further provide an initiation point for the domain-swapping and mutagenesis experiments among different Cry toxins.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sequence Data

The amino acid sequence of the putative Cry1Ab15 protein of Bacillus thuringiensis was retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. The sequence accession number was AAO13302. It was ascertained that the three-dimensional structure of the protein was not available in the Protein Data Bank; hence, the present exercise of developing the three-dimensional model was undertaken.

2.2. Template Selection and Structure Prediction

Homology method-dependent modeling is an effective approach for a three-dimensional structure of protein provided by an experimentally obtained three-dimensional structure of homologous protein. All experimentally determined homologous protein can serve as a template for modeling. Since template selection is an important factor that affects quality, therefore, an attempt was made for a suitable template searching using mGenTHREADER [14], which is an online tool for searching similar sequences, based on sequence and structure-wise similarity. The target protein was 577 amino acid long stretches. From the homologous searching, Cry1Aa (PDB: 1CIY, resolution 2.25 Å) was selected as a template protein. Finally, amino acid sequence alignment between the target (Cry1Ab15) and template protein was derived using the MEGA4 software [15]. The three-dimensional structure of target protein was predicted by using the alignment file in MODELLER software [16] whereby predicted structure was returned.

2.3. Homology Modeling of Cry1Ab15

The possible outliers and side chains static constrain refinement of the developed model was performed on Summa Lab server [17] after the selected theoretical model were further subjected to a series of tests for evaluating its consistency and reliability. Backbone confirmation was evaluated by the inspection of the Psi/Phi Ramachandran plot from RAMPAGE web server [18]. The energy criterion was evaluated by ProSA web server [19], which compares the potential of mean forces derived from a large set of NMR and X-ray crystallographically derived protein structures of similar sizes. Potential deviations were calculated by SUPERPOSE web server [20] for root mean square deviations (RMSD) between target and template protein structure. The comparative analysis of generated model showed it to be superimposable. The secondary structure visualization was made using PDBsum [21], and amino acid sequence alignments are generated with SAS software [22] (Figure 1). The visualization of models was performed on UCF Chimera software [23] and PyMOL [24] loaded on a personal computer machine that has an Intel Quad core processor and four gigabytes of random accessed memory. Figures and electrostatic potential calculations were generated with PyMOL0.99rc6. The final model was submitted to the PMDB database [25] to obtain protein model databank (PMDB) identifier PM0076556.

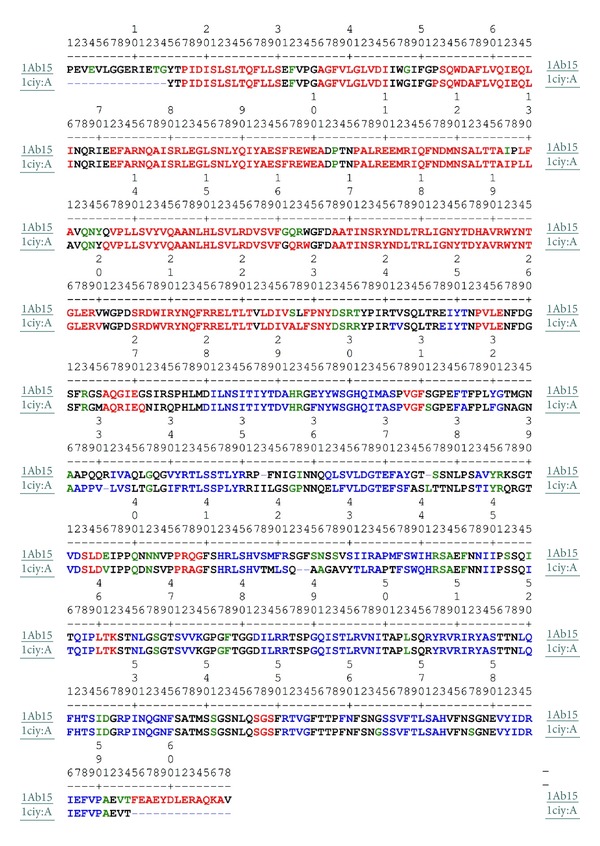

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the Cry1Ab15 with Cry1Aa (1ciy: A). The residues highlighted in red color represent helix; those in blue represent strand; in green represent turn; and those in black represent coil, and alignment is generated using SAS software.

3. Results and Discussion

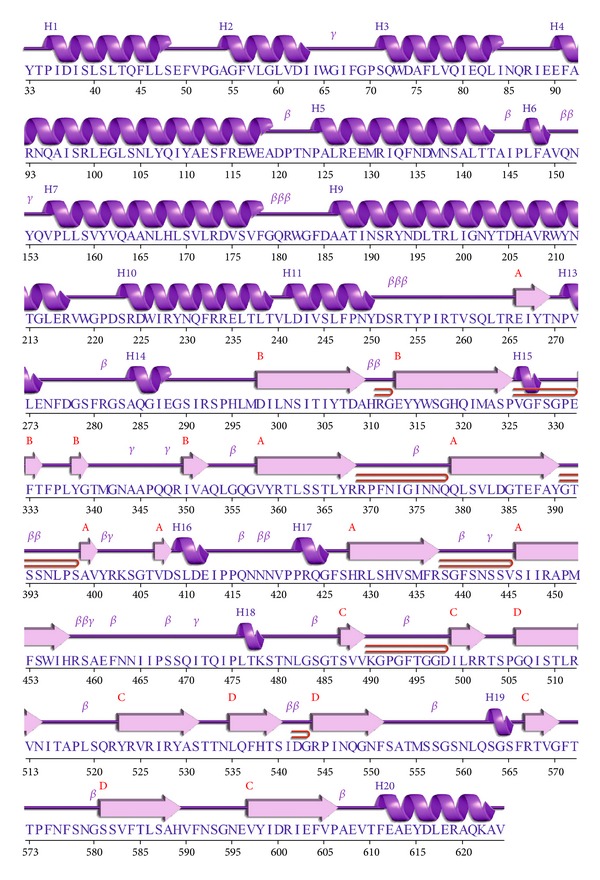

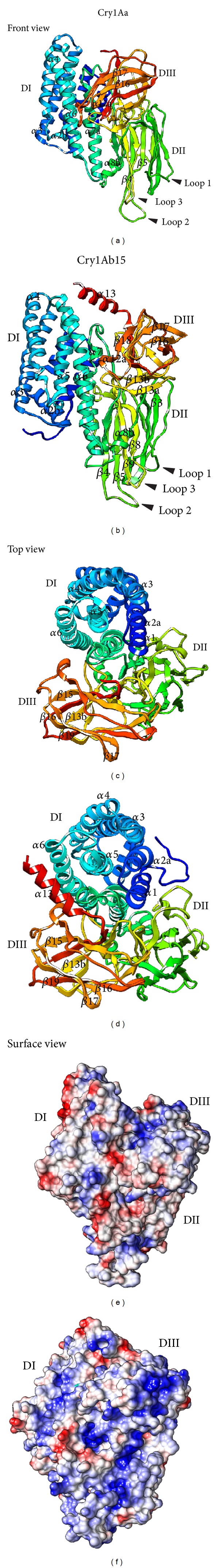

Sequence alignment showed 88.3% identity (Smith Waterman Score-3356; Z-Score-3981.3; E Value-6.4e-215) between the Cry1Ab15 and Cry1Aa. It is observed that a model tends to be reliable if identity percentage between the template and target protein is above 40%. Low degree of reliability arises when identity decreases below 20% [26]. Identity difference in the present case is sufficiently high to carry out the theoretical modeling for the Cry1Ab15 toxin stretch of 84–661 residues (Figure 1). Sequence alignment of domain I, domain II, and domain III was straightforward within the possible limits of flanking domains. Domain III is quite well conserved both on the N-terminal and C-terminal sides. Domain I is composed of residues 86–341 and consists of 9 α-helices and too small β-strands. All the helices in the Cry1Ab15 model were slightly longer than those in Cry1Aa (Table 1). The amphiphilicity (Hoops and Woods) values indicated an exposed nature of a few of the helices of domain I (α1, α2a, α2b, α3, and α6). These values correspond well with the accessibility calculated with Swiss PDB, except for α1, which is packed against domain II (Figure 2). It is possible that this helix will have some mobility, with an emphasis that one of the cutting sites by gut proteases is located close to the middle of this helix [27]. On the other hand, membrane insertion and pore formation are thought to occur through elements of domain I, composed of a bundle of six amphipathic α-helices surrounding the highly hydrophobic helix α5 [7]. Spectroscopic studies with synthetic peptides corresponding to domain I helices revealed that α4 and α5 have the greatest propensity for insertion into artificial membranes, although insertion and pore formation were more efficient when α4 and α5 were connected by a segment analogous to the α4-α5 loop of the toxin [28, 29]. A particularly large number of single-site mutations with altered amino acids from these helices, which lead to a strong reduction in the toxicity and pore-forming ability of the toxin, have been characterized [30–33]. Also, a site-directed chemical modification study has provided strong evidence that α4 lines the lumens of the pores formed by the toxin [34]. Recent studies have established that toxin activity is especially sensitive to modifications not only in the charged residues of α4 [33] but also in most of its hydrophilic residue [30]. Furthermore, the loss of activity of most of these mutants did not result from an altered selectivity or the size of the pores, but from a reduced pore-forming capacity of the toxin [34]. The charge distribution pattern in the Cry1Ab15 theoretical model corresponds to a negatively charged patch along β4 and β13 (Figures 3 and 4) of domains II and III, respectively. The Cry1Ab15 domain I model relates well with the data from Gerber and Shai [29] who have suggested that α4 and α5 insert into the membrane in an antiparallel manner as a helical hairpin. It is possible that according to the surface electrostatic potential of helices 4 and 5 there was a neutral region in the middle of the helices which probably indicates, if we follow the umbrella model and consider it to be correct, that both helices cross the membrane with their polar sides exposed to the solvent as it has been suggested by the results of mutagenesis experiments done by Girard et al. [31] with the Cry1Ac toxin. This region is also the most conserved among the Cry toxins. Girard et al. [31] demonstrated that mutations in the base of helix 3 and the loop between α3 and α4 that cause alterations in the balance of negative charged residues may cause loss of toxicity. Mutations in helices α2 and α6 and the surface residues of α3 have no important effect on toxicity; meanwhile, helices α4 and α5 seem to be very sensitive to mutations. Helix α1 probably does not play an important part in toxin activity after the cleavage of the protoxin. It is possible that the mutations aimed to an increasing the amphiphilicity in these helices will improve the pore-forming activity of the Cry1Ab15 type toxins. The structure of domain I of the toxin, the effect of site-directed mutagenesis in this domain on toxin activity, and the studies with hybrid toxins [35–37] all suggest that domain I, or parts of it, inserts 125 into the membrane and forms a pore. This idea is further supported by studies that show that truncated proteins corresponding to domain I of CryIA(c) [38] δ-endotoxin form ion channels in model lipid membranes similar to those formed by the intact toxins. After receptor binding, the network of contacts between α7, the helix in the interface between the pore-forming domain and the receptor-binding domain, and α5, α6, and, presumably, α4 helices may assist at the insertion of the α4-α5 hairpin into the membrane by the unpacking of the helical bundle that exists in the nonmembrane-bound form of the toxin. This hypothesis might account for the observation that α7 mutants are susceptible to proteolysis by either trypsin or midgut juice [39]. Our model also supports the notion that the α4-α5 hairpin is the major structural component in the lining of the pores formed by δ-endotoxin. Therefore, it is possible to create toxin variants with better membrane permeability potential by stabilizing the hairpin antiparallel structure by cross-linking α4 with α5. This postulation is important because mutations within transmembrane segments of proteins usually decrease or have no effect on the biological activities of these proteins. Thus, it is conceivable that the introduction of several salt bridges or other bonds between α4-α5 helices or the stabilization of the α4-α5 hairpin by the creation of bridging interactions between the α3-α4 and α5-α6 loops may result in a significantly enhanced toxic activity. Other studies also support the umbrella-like model for domain I insertion into membranes [34, 40, 41]. As for other Cry toxins, domain II of the Cry1Ab15 toxin consists of three Greek key beta sheets arranged in a beta prism topology. It is comprised of residues 350–508, one helix (α8), and 11 β-strands (Table 1). In the case of the three domain Cry toxins, specificity is mostly attributed to their capacity to bind to certain proteins located on the surface of the intestinal membrane through specific segments of domains II and III, composed mainly of β sheets [42, 43]. Loop β4-β5 is mostly hydrophilic, and the charged residues located at the tip of the loop are probably important determinants of insect specificity. As in loop β2-β3, few glycine residues are also present before a negatively charged residue supporting the hypothesis that correct orientation of charged residues in the specificity loops could be important in receptor recognition. Mutations in defined regions of the Cry1Aa toxin have identified residues 365–371 (equivalent to residues in the Cry1Ab15 β6-β7 loop) as essential for binding to the membrane of midgut cells of Bombyx mori [35, 44]. In the Cry1Ab15 model, this region is shorter than their counterparts in Cry1Aa. Loop β2-β3 seems also to be able to modulate the toxicity and specificity of Cry1C [45]. The dual specificity of Cry2Aa for Lepidoptera and Diptera has been mapped to residues 307–382 that corresponds in the Cry1Ab15 theoretical model to sheet 1, strand β6, and loop β6-β7. Domain III comprised residues 471–608 and showed high conservation of residues and the only important modification is a 3-residue deletion between β16 and β17. Several studies indicate that site mutations in conserve blocks reduce toxicity and alter channel properties at least in Cry1Ac [7] and Cry1Aa [42, 46], and divergence in block 5 element [8, 41] postulates an alternative mechanism of membrane permeabilization.

Table 1.

The comparison among three-domain structural components of Cry1Aa and Cry1Ab15 toxin molecules.

| Domain I | Domain II | Domain III | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cry1Aa | Cry1Ab15 | Cry1Aa | Cry1Ab15 | Cry1Aa | Cry1Ab15 | |||

| β0 | — | Thr31-Tyr33 | α8a | Pro271-Glu274 | Pro271-Asn275 | α11a | Leu475-Lys477 | — |

| α1 | Pro35-Ser48 | Pro35-Ser48 | α8b | Ala284-Gln289 | Ser283-Ser290 | β13a | Ser486-Val488 | Ser487-Val489 |

| α2a | Aln54-Ile63 | Aln54-Trp65 | β2 | Asp298-His310 | Ile299-His310 | β13b | Ile498-Arg501 | Ile499-Arg502 |

| α2b | Pro70-Ile84 | Pro70-Ile84 | β3 | Phe313-Trp316 | Glu313-Ser324 | β14 | Gly505-Asn513 | Gly506-Asn514 |

| α3 | Glu90-Ala119 | Glu90-Ala119 | β4 | Gly318-Pro325 | Tyr359-Arg368 | β15 | Tyr522-Ser530 | Tyr523-Ala530 |

| α4 | Pro124-Leu148 | Pro124-Leu148 | α9 | Val326-Phe328 | *Ser409-Glu412 | β16 | Leu534-Ile540 | Leu534-Ile541 |

| α5 | Gln154-Trp182 | Val155-Trp182 | β5 | Val348-Ser351 | Leu380-Tyr390 | β17 | Arg543-Phe550 | Arg544-Phe551 |

| α6 | Ala186-Val218 | Ala186-Val218 | β6 | Ile357-Arg367 | Ala399-Tyr401 | α12a | Ser562-Ser564 | Ser563-Ser565 |

| α7a | Ser223-Thr239 | Ser223-Tyr250 | β7 | Leu380-Leu383 | Thr406-Asp408 | β18 | Arg566-Gly569 | Arg567-Phe571 |

| α7b | Leu241-Tyr250 | — | β8 | Gly385-Phe390 | His428-Arg437 | β19 | Ser580-His588 | Ser581-His589 |

| β1a | Glu266-Thr269 | — | β9 | Thr400-Tyr402 | Ile447-His457 | β20 | Val596-Pro605 | Val597-Pro606 |

| α10a | Ser410-Asp412 | — | α13 | — | Phe611-Ala623 | |||

| α10b | Pro423-Gly426 | — | ||||||

| β10 | His429-Val434 | Gln473-Pro475 | ||||||

| β11 | Phe452-His456 | Thr480-Leu482 | ||||||

| β12 | Thr471-Pro474 | — | ||||||

—: similar component not present. *Components in italics are spatially present at downstream sites.

Figure 2.

The two-dimensional structure annotation showing sequential arrangements of helices and sheets in Cry1Ab15 toxin molecule using the PDB Sum (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbsum/). The structure is as the spiral shape are helix labeled as H1 and H2; and the arrows as strands are labeled by their sheets A and B while motifs β are beta turn and γ are gamma turn while the bend tube shape is a beta hairpin.

Figure 3.

The comparative three-dimensional, three-domain structure of the Cry1Ab15 ((b), (d), (f)) and Cry1Aa ((a), (c), (e)) molecules.

Figure 4.

The comparative figures separately showing details among three structural domains of Cry1Ab15 and Cry1Aa molecules.

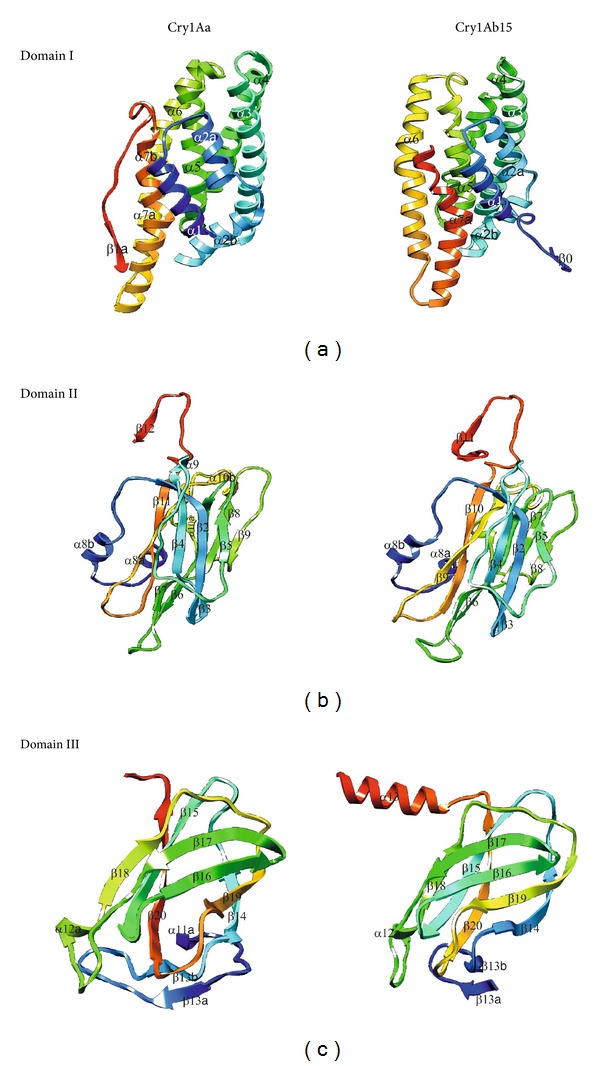

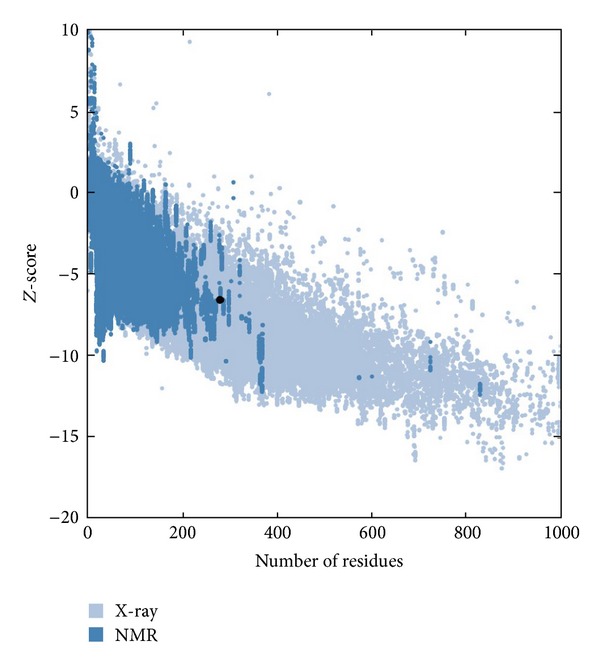

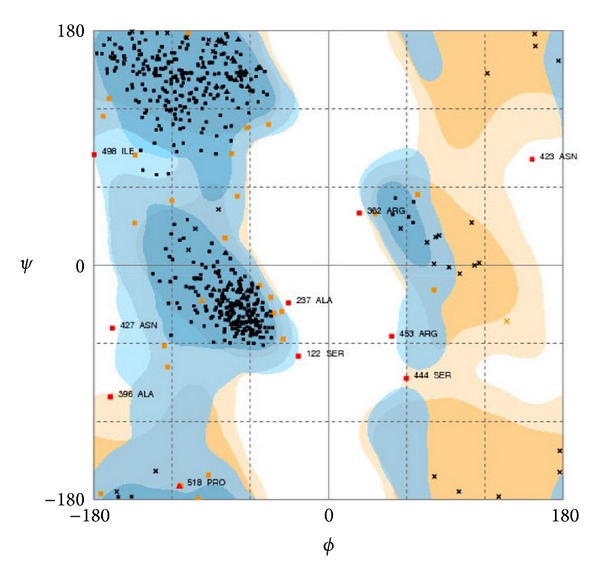

Finally, the recognition of artefacts and errors in experimental and theoretical structures remains a problem in the field of structure modeling. A structural comparison of Cry1Aa toxin with the theoretical model of the Cry1Ab15 protein indicates correspondence with the general model for a Cry protein the superimposed backbone traces showed low RMS deviations (Figure 5). The comparison between the overall energy of developed structure and those of experimentally determined structures in PROSA database validated the developed model as folded near to experimentally determined, natural structures (Figure 6) while the Ramachandran plot analysis (Figure 7) supported the above conclusions by showing that most of the residue (98%) has φ and ψ angles in the core- and allowed-regions, except for nine residues which qualified for outlier region. Most bond lengths, bond angles, and torsion angles were in the range of values expected for a naturally folded protein (Figure 7).

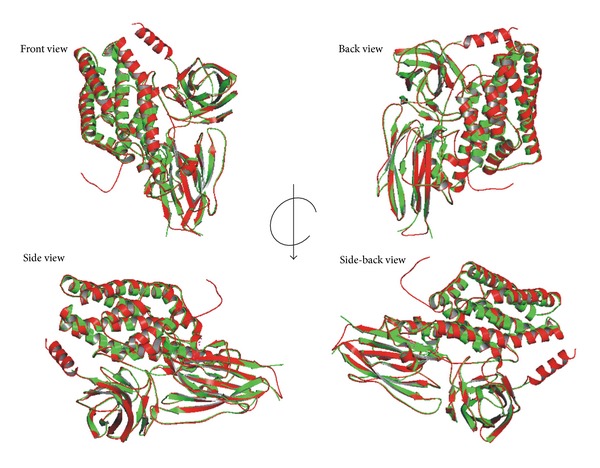

Figure 5.

Superimposed backbone 3D structure between Cry1Aa1 (green) and Cry1Ab15 (red) coordinates. The RMSD for backbone and alpha carbons is 1.15. The image was generated using the SUPERPOSE software (http://wishart.biology.ualberta.ca/SuperPose/).

Figure 6.

Evaluation of Cry1Ab15 using ProSA server (https://prosa.services.came.sbg.ac.at/). The plot indicating nearness of constructed structure with the native structures. The Z-score of evaluated model was −6.56, shown as a large black dot.

Figure 7.

Ramachandran plot analysis of the Cry1Ab15 toxin oligomer showing placement of residues in deduced model. General plot statistics are: 94.0% (568/604) of all residues were in favored (98%) regions residues in additional allowed regions 99.0% (598/604) of all residues were in allowed (>99.8%) regions. The figure was generated using RAMPAGE web server (http://mordred.bioc.cam.ac.uk/).

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, evidence presented here, based on the identification of structural equivalent residues of Cry1Aa in Cry1Ab15 toxin through homology modeling, indicates that due to the high amino acid homology between these two toxins, they do share a common three-dimensional structure. Cry1Aa and Cry1Ab15 contain the most variable regions in the loops of domain II, which is responsible for the specificity of these toxins. Structural comparison indicates a correspondence to the general model for a Cry protein (an α + β structure with three domains) and few of the differences present are the presence of 175 β0 and α3 the absence of α7b, β1a, α10a, α10b, β12, and α11a while α9 is located spatially downstream. This is the first model of a Cry1Ab15 protein and its importance can be perceived since the members of this group of toxins are potentially important entomopathogenic candidates.

Conflict of Interests

The author declares that he has no direct financial relation with the commercial identities mentioned in the paper that might lead to a conflict of interests including the necessary citation.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to ICAR for fellowship. Infrastructure facility and encouragement of the Director NBAIM are duly acknowledged.

References

- 1.Roh JY, Choi JY, Li MS, Jin BR, Je YH. Bacillus thuringiensis as a specific, safe, and effective tool for insect pest control. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2007;17(4):547–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofmann C, Vanderbruggen H, Hofte H, van Rie J, Jansens S, van Mellaert H. Specificity of Bacillus thuringiensisδ-endotoxins is correlated with the presence of high-affinity binding sites in the brush border membrane of target insect midguts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85(21):7844–7848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boonserm P, Davis P, Ellar DJ, Li J. Crystal structure of the mosquito-larvicidal toxin Cry4Ba and its biological implications. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005;348(2):363–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boonserm P, Mo M, Angsuthanasombat C, Lescar J. Structure of the functional form of the mosquito larvicidal Cry4Aa toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis at a 2.8-angstrom resolution. Journal of Bacteriology. 2006;188(9):3391–3401. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.9.3391-3401.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derbyshire DJ, Ellar DJ, Li J. Crystallization of the Bacillus thuringiensis toxin Cry1Ac and its complex with the receptor ligand N-acetyl-D-galactosamine. Acta Crystallographica D. 2001;57(12):1938–1944. doi: 10.1107/s090744490101040x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galitsky N, Cody V, Wojtczak A, et al. Structure of the insecticidal bacterial δ-endotoxin Cry3Bb1 of Bacillus thuringiensis . Acta Crystallographica D. 2001;57(8):1101–1109. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901008186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grochulski P, Masson L, Borisova S, et al. Bacillus thuringiensis CryIA(a) insecticidal toxin: crystal structure and channel formation. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1995;254(3):447–464. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Carroll J, Ellar DJ. Crystal structure of insecticidal δ-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature. 1991;353(6347):815–821. doi: 10.1038/353815a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morse RJ, Yamamoto T, Stroud RM. Structure of Cry2Aa suggests an unexpected receptor binding epitope. Structure. 2001;9(5):409–417. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutierrez P, Alzate O, Orduz S. A theoretical model of the tridimensional structure of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. medellin Cry 11Bb toxin deduced by homology modelling. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96(3):357–364. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xin-Min Z, Li-Qiu X, Xue-Zhi D, Fa-Xiang W. The theoretical three-dimensional structure of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry5Aa and its biological implications. Protein Journal. 2009;28(2):104–110. doi: 10.1007/s10930-009-9169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia LQ, Zhao XM, Ding XZ, Wang FX, Sun YJ. The theoretical 3D structure of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry5Ba. Journal of Molecular Modeling. 2008;14(9):843–848. doi: 10.1007/s00894-008-0318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28(1):235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchan DWA, Ward SM, Lobley AE, Nugent TCO, Bryson K, Jones DT. Protein annotation and modelling servers at University College London. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38(2):W563–W568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24(8):1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sali A, Potterton L, Yuan F, van Vlijmen H, Karplus M. Evaluation of comparative protein modeling by MODELLER. Proteins. 1995;23(3):318–326. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Summa CM, Levitt M. Near-native structure refinement using in vacuo energy minimization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(9):3177–3182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611593104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;35:W375–W383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;35:W407–W410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maiti R, van Domselaar GH, Zhang H, Wishart DS. SuperPose: a simple server for sophisticated structural superposition. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32:W590–W594. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laskowski RA, Chistyakov VV, Thornton JM. PDBsum more: new summaries and analyses of the known 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33:D266–D268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milburn D, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. Sequences annotated by structure: a tool to facilitate the use of structural information in sequence analysis. Protein Engineering. 1998;11(10):855–859. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.10.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Version 1.2r3pre, PyMol was used for visualization of models. Schrödinger, LLC.

- 25.Castrignanò T, De Meo PD, Cozzetto D, Talamo IG, Tramontano A. The PMDB protein model database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:D306–D309. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chothia C, Lesk AM. The relation between the divergence of sequence and structure in proteins. The EMBO Journal. 1986;5(4):823–826. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Segura C, Guzman F, Patarroyo ME, Orduz S. Activation pattern and toxicity of the Cry11 bb1 toxin of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. medellin . Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 2000;76(1):56–62. doi: 10.1006/jipa.2000.4945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu H, Rajamohan F, Dean DH. Identification of amino acid residues of Bacillus thuringiensisδ-endotoxin CryIAa associated with membrane binding and toxicity to Bombyx mori . Journal of Bacteriology. 1994;176(17):5554–5559. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5554-5559.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerber D, Shai Y. Insertion and organization within membranes of the δ-endotoxin pore-forming domain, helix 4-loop-helix 5, and inhibition of its activity by a mutant helix 4 peptide. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(31):23602–23607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gazit E, La Rocca P, Sansom MSP, Shai Y. The structure and organization within the membrane of the helices composing the pore-forming domain of Bacillus thuringiensisδ-endotoxin are consistent with an “umbrella-like” structure of the pore. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(21):12289–12294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girard F, Vachon V, Préfontaine G, et al. Cysteine scanning mutagenesis of α4, a putative pore-lining helix of the Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxin Cry1Aa. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008;74(9):2565–2572. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00094-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar ASM, Aronson AI. Analysis of mutations in the pore-forming region essential for insecticidal activity of a Bacillus thuringiensisδ-endotoxin. Journal of Bacteriology. 1999;181(19):6103–6107. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.6103-6107.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nuez-Valdez ME, Sánchez J, Lina L, Güereca L, Bravo A. Structural and functional studies of α-helix 5 region from Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ab δ-endotoxin. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2001;1546(1):122–131. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(01)00132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coux F, Vachon V, Rang C, et al. Role of interdomain salt bridges in the pore-forming ability of the Bacillus thuringiensis toxins Cry1Aa and Cry1Ac. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(38):35546–35551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101887200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masson L, Tabashnik BE, Liu YB, Brousseau R, Schwartz JL. Helix 4 of the Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Aa toxin lines the lumen of the ion channel. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(45):31996–32000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.31996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ge AZ, Shivarova NI, Dean DH. Location of the Bombyx mori specificity domain on a Bacillus thuringiensisδ-endotoxin protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86(11):4037–4041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmad W, Ellar DJ. Directed mutagenesis of selected regions of a Bacillus thuringiensis entomocidal protein. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 1990;68(1-2):97–104. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90132-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu D, Aronson AI. Localized mutagenesis defines regions of the Bacillus thuringiensisδ endotoxin involved in toxicity and specificity. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267(4):2311–2317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walters FS, Slatin SL, Kulesza CA, English LH. Ion channel activity of N-terminal fragments from CryIA(c) δ-endotoxin. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1993;196(2):921–926. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dean DH, Rajamohan F, Lee MK, et al. Probing the mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal proteins by site-directed mutagenesis—a minireview. Gene. 1996;179(1):111–117. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00442-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gazit E, Burshtein N, Ellar DJ, Sawyer T, Shai Y. Bacillus thuringiensis cytolytic toxin associates specifically with its synthetic helices A and C in the membrane bound state. Implications for the assembly of oligomeric transmembrane pores. Biochemistry. 1997;36(49):15546–15554. doi: 10.1021/bi9707584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwartz JL, Potvin L, Chen XJ, Brousseau R, Laprade R, Dean DH. Single-site mutations in the conserved alternating-arginine region affect ionic channels formed by CryIAa, a Bacillus thuringiensis toxin. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1997;63(10):3978–3984. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.3978-3984.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pigott CR, Ellar DJ. Role of receptors in Bacillus thuringiensis crystal toxin activity. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2007;71(2):255–281. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00034-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gómez I, Pardo-López L, Munoz-Garay C, et al. Role of receptor interaction in the mode of action of insecticidal Cry and Cyt toxins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis . Peptides. 2007;28(1):169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith GP, Ellar DJ. Mutagenesis of two surface-exposed loops of the Bacillus thuringiensis CrylC δ-endotoxin affects insecticidal specificity. Biochemical Journal. 1994;302(2):611–616. doi: 10.1042/bj3020611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen XJ, Lee MK, Dean DH. Site-directed mutations in a highly conserved region of Bacillus thuringiensisδ-endotoxin affect inhibition of short circuit current across Bombyx mori midgets. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90(19):9041–9045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]