Abstract

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a highly prevalent urinary syndrome with a profound impact on quality of life (QoL) of affected patients and their family because of its adverse effects on social, sexual, interpersonal, and professional function. Cost-of-illness analyses showed the huge economic burden related to OAB for patients, public healthcare systems, and society, secondary to both direct and indirect costs; however, intangible costs related to QoL impact are usually omitted from these analyses. Recently many novel treatment modalities have been introduced and the need to apply the modern methodology of health technology assessment to these treatment strategies was immediately clear in order to evaluate objectively their value in term of both improvement in length/quality of life and costs. Health utilities are instruments that allow a measurement of QoL and its integration in the economic evaluation using the quality-adjusted life-years model and cost-utility analysis. The development of suitable instruments for quantifying utility in the specific group of OAB patients is vitally important to extend the application of cost-utility analysis in OAB and to guide healthcare resources allocation for this disorder. Studies are required to define the cost-effectiveness of available pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapy options for this disorder.

Keywords: overactive bladder, burden, health utility, cost-utility

Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) is defined by the International Continence Society (ICS) as ‘urgency (a sudden, compelling desire to urinate, which is often difficult to defer) with or without urge incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia’.1 OAB may present as a purely sensitive disorder, although overactivity (spontaneous, uninhibited contractions) of the bladder detrusor muscle represents the most common underlying idiopathic or neurogenic dysfunction.2 For the majority of patients with OAB the underlying etiology remains unknown, even though age is the most important risk factor for the condition.3,4

Epidemiological studies on OAB have suffered a number of problems, including the subjective nature of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), the focus centered on urge urinary incontinence (UUI) only, and the recent change in the definition of the syndrome which makes most previous studies inconsistent with its current description. Furthermore, OAB prevalence is considered to be underestimated because most patients do not seek medical care due to social and cultural factors, particularly when UI is present.3,5–7 The international standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function enabled valuable and more reliable epidemiologic information on OAB to be obtained.1 In the last few years, many studies have provided evidence for the high prevalence of this condition.3–5,8

The population-based prevalence SIFO survey, conducted in 6 European countries in 1997 to 1998, estimated an OAB prevalence of 15.6% in men and 17.4% in women.3 In these reports, frequency was the most commonly reported LUTS (85%), followed by urgency (54%) and UUI (36%). A significant increase in OAB prevalence was observed with increased age, with 41.9% of men and 31.3% of women over 75 years suffering from OAB. Overall, 60% of respondents with OAB symptoms had consulted a doctor but only 27% were currently receiving treatment.3

The first survey reporting OAB prevalence in a noninstitutionalized US adult population aged ≥ 18 years and using validated symptom-based criteria was the National Overactive Bladder Evaluation (NOBLE) program.4 Estimation of OAB prevalence in US was 16% in men and 16,9% in women, with a global number of 33 million citizens suffering from OAB symptoms.4

The most important recent data on OAB prevalence came from the EPIC study8 which used the 2002 ICS definition.1 It was a cross-sectional, population-based, telephone survey of people aged ≥ 18 years, conducted in Canada, Germany, Italy, Sweden, and the UK. The overall prevalence was 11.8% (10.9% for men and 12.9% for women) and increased with age. OAB was more prevalent than all types of UI combined (9.4%). The prevalence varied by country with the lowest reported prevalence in Canada (8.0% men; 8.9% women) and the highest in Sweden (13.2% men; 19.6% women). The estimated prevalence rate of UUI was 1.8% in men and 3.9% in women.8

The recent evolution on the awareness and treatment of OAB has encouraged studies on the economic burden related to this syndrome. OAB and the accompanying UI revealed to be a heavy financial burden to the patient and society. The need to apply the modern methodology of health technology assessment (HTA) to the available therapy options became immediately clear in order to objectively evaluate their costs and guide stakeholders in their decisions on resources allocation.

The present article reports on the most recent knowledge on the socioeconomic burden of OAB syndrome and on the economics of interventions applied to the OAB treatments.

Socioeconomic burden

Quality of life and social impact

OAB has been shown to have a negative impact on many aspects of patients’ quality of life (QoL).3,4,8–14 LUTS associated with OAB are responsible of significant social, psychological, occupational, domestic, and physical stigmas.11 Depression is strongly associated with OAB.14–16 OAB patients become anxious in unfamiliar surroundings: they focus on and may be preoccupied with such concerns as locating the closest bathroom, looking for aisle seating, and estimating the amount of time until their next work break.14,17 Embarrassment, frustration, anxiety, annoyance, depression, and fear of odor can have a negative impact on daily activities, such as travel, physical activity, interpersonal relationships, and sexual function, resulting in social isolation.14,17 The nocturia that is often experienced by people with OAB diminishes quality of sleep and increases the risk for fall and hip fracture in elderly, osteoporotic female patients.9,11,18 Many patients also develop elaborate coping behaviors aimed at hiding and managing urine loss, such as reducing fluid intake, avoiding sexuality and social activities, wearing and carryng extra clothes and pads, and sitting closest to the door for easier access to the bathroom.7

OAB with UUI (‘wet OAB’) appears to affect QoL more than dry OAB.14,19–21 Results of the European survey published by Irwin et al14 showed that participants with wet OAB were significantly more likely than those with dry OAB to express worry about having accidents and concern about participating in activities away from home. Accordingly, the results of the NOBLE program showed that OAB patients presented higher symptom bother scores than controls, with wet OAB patients reporting a higher impact of symptoms on physical function, role limitation, vitality, general health perception, bodily pain, and social function.4

Studies showed that not only UUI, but storage LUTS as well (urgency, frequency and nocturia) strongly impair patients’ QoL.3,4,8,22 In the SIFO study, Milsom et al3 reported that more than 65% of OAB patients report that their LUTS negatively affect their daily lives. Urinary frequency also was shown to have a negative impact on QoL, although lower compared with urgency.22

In both men and women, OAB symptoms have been associated with impaired sexual activity and sexual dysfunctions. In men, the severity of LUTS has been associated with decreased sexual activity and satisfaction and with erectile dysfunction (ED).23–27 Using data from the EPIC study, Irwin et al26 reported that the prevalence of sexual dysfunction, including ED, was greater in men with LUTS (cases), including OAB, than in men without LUTS (controls). OAB, with or without UUI, negatively affects also women’s sexual health, reducing sexual desire, genital lubrification, orgasm and satisfaction.28–30 Women with urodynamically proven detrusor overactivity had greater emotional problems, worse marital relationships, and lower sexual satisfaction compared to women with normal urodynamic evaluation in the study by Yip et al.29 These women had a significantly worse total sexual function also when compared to those with other lower urinary tract dysfunctions, such as stress or mixed UI or sensory urgency, or normal urodynamics.30

Various research has reported significantly less work productivity in OAB patients.4,8,22,23,31,32 In the EPIC study, authors used the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment instrument (WPAI) to explore the work productivity in their survey.8,23 The WPAI is a series of questions on the number of hours missed from work, the number of hours worked, and days during which work was difficult, followed by a rating of the extent to which the individual was limited at work during the past 7 days.33 Participants with OAB reported a greater impairment than controls on two of the three scales of the WPAI (both P < 0.001), and almost a quarter of cases aged <65 years reported some form of work impairment, versus 12.2% of controls (P < 0.001).23 Accordingly, data from the EPIC showed that men and women with OAB (both wet and dry) were more likely to report absenteeism compared with controls.31 Findings indicated that a substantial proportion of OAB patients (particularly those with UUI) worry about interrupting meetings and have considered their urinary symptoms in decisions about work location and hours.31 Using data from the EpiLUTS survey conducted in USA, UK, and Sweden, Sexton et al32 reported in a population of 2876 men and 2820 women, aged 40 to 65 and working full- or parttime, that men and women with wet OAB had the lowest levels of work productivity and highest rates of daily work interference.

Studies indicated that OAB has also a substantial impact on family members, even among those who did not live with the patients. Recently, Coyne et al34,35 found that nearly all family members reported that the patients’ urinary frequency significantly limited a wide range of activities they could do together because of the patients’ persistent, and often urgent, need to find a toilet. Family members also indicated that their partner’s OAB had a powerful emotional impact including embarrassment, anxiety, anger, worry, irritation, stress, frustration, annoyance, and strain on the relationship. Spouses and significant others reported that the patients’ nocturia caused sleep disruption and resulting fatigue.34

Quality of life instruments

Health status, health-related QoL (HRQL) impact and treatment-related HRQL changes can be objectively assessed by using psychometrically robust self-completion questionnaires, the only valid way of measuring the patient’s perspective of their health state, disease and treatment-related QoL changes.36 Several different questionnaires have been developed to assess the health-related QoL HRQL impact of OAB; however the ICS recommends the use of instruments with proven validity, reliability, and responsiveness.36,37 Collectively, such measures are called patient-derived outcome (PRO) questionnaires. PROs are used in real-world clinical practice, clinical trials, health economic research and health care planning. Table 1 presents the different classes of HRQL instruments.

Table 1.

Types of quality-of-life (QoL) questionnaires

| Type of questionnaire | Properties of questionnaire |

|---|---|

| Generic | Measure very broad aspects of health and are suitable for a wide range of patient groups (eg, MOS SF-36,38 Nottingham Health Profile [NHP], Sickness Impact Profile [SIP]) |

| Disease-specific | Measure patients’ perception of a specific disease or health problem. These can be either specific to certain types of problem, ie, LUT dysfunction (KHQ, BFLUTS, I-QOL)47,49,51 or a specific aspect of that problem, ie, OAB specific (eg, OAB-q).44 They offer greater sensitivity and responsiveness to change in the assessment of QoL of specific patient groups |

| Dimension-specific | Assess one particular aspect of health status, usually psychological wellbeing (eg, Beck Depression Inventory – assess symptoms of depression and ICIQ) |

| Summary items | Ask patients to summarise diverse aspects of their health status using a single item or a very small number of items (eg, UPS, PBC).44,53,54 They are useful in conditions such as OAB that have multiple and varied symptoms, and reflect an individual’s needs, concerns and values |

| Individualized | Allow patients to identify for themselves the most important aspects of their lives that influence their appraisal of their overall QoL – these measures have not been widely used in the assessment of incontinence and LUTS (eg, patient-generated index) |

| Utility measures | Incorporate preferences or values attached to individual health states and express health states as a single index (eg, SF-6D,38,42,43 EQ-5D).112,113 These are of particular value in health economic analyses |

Reproduced from Basra R, Kelleher C. Disease burden of overactive bladder: quality-of-life data assessed using ICI-recommended instruments. Pharmacoeconomic. 2007;25:129–142.36 Copyright © 2007 with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health.

Abbreviations: BFLUTS, Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms; ICIQ, International Consultation on Incontinence questionnaire; I-QOL, Incontinence Quality of Life questionnaire; KHQ, Kings Health Questionnaire; LUT, lower urinary tract; LUTS, LUT symptoms; MOS SF-36, Medical Outcomes Survey 36-item short-form; NHP, Nottingham Health Profile; OAB, overactive bladder; OAB-q, Overactive Bladder Questionnaire; PBC, Patient Perception of Bladder Condition; SIP, Sickness Impact Profile; UPS, Urgency Perception Scale.

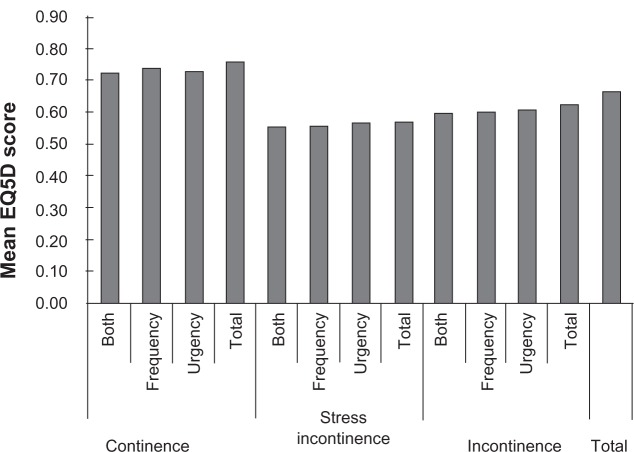

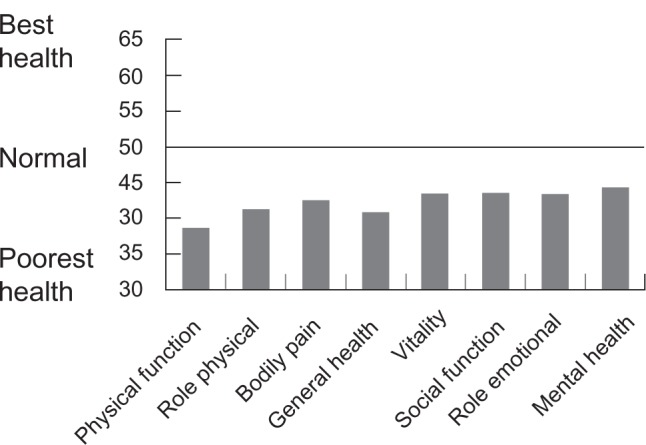

Generic instruments can be applied to patients with any medical condition and provide a valuable measure of a person’s current health status, although they are less sensitive to clinically relevant changes in conditions such as OAB.36 The Medical Outcomes Survey 36-item short form (SF-36) is the most commonly used generic HRQL questionnaire in LUTS research.38 It consists of a single item assessing health transition, and an 8-scale profile of physical and mental health. Short-form versions (SF-20 and SF-12) have been developed. The SF-36 was used both in cross-sectional surveys and in clinical trials.22,39,40–43 As measured by the SF-36, the HRQL of those with OAB is impaired when compared with the general population (Figure 1).4,22,39,40 OAB patients scored significantly lower in most of SF-36 domains; only patients with depression scored consistently lower than those with OAB.39,40

Figure 1.

Results of SF-36: QoL scores of a Swedish cohort of OAB patients compared to normalized scores from the general population, controlled for age and sex, but not for comorbidity. All domains are significantly lower than the normal (P < 0.001). For all scales the mean (SD) score in the general population is standardized to 50. Reproduced with permission from Kobelt G, Kirchberger I, Malone-Lee J. Quality-of-life aspects of the overactive bladder and the effect of treatment with tolterodine. BJU Int. 1999;83:583–590.139 Copyright © 1999 Wiley-Blackwell.

Some HRQL condition-specific questionnaires are recommended by ICI as ideal research tool to explore the impact on patients’ QoL of UI and LUTS and to assess outcome from various treatment modalities. The Overactive Bladder Questionnaire (OAB-q) is the most widely used validated condition-specific instrument specifically designed to assess the symptom bother and QoL specifically in OAB patients.44 The OAB-q consists of an 8-item symptom bother scale and 25 HRQL items that form 4 subscales and a total HRQL score. The questionnaire, also available in a shortened version (OAB-q SF), has been incorporated into the ICI Modular Questionnaire (ICIQ) as the ICIQ-OABqol.45 The OAB-q has been used as part of the clinical assessment of patients in a number of clinical trials comparing the efficacies of pharmacological therapies for OAB. It has been shown to be responsive to treatment and psychometrically valid with strong internal consistency, reliability and construct validity.44,46

The Kings Health Questionnaire (KHQ) is a 33-item multidimensional disease-specific validated questionnaire originally designed to assess the impact of UI on QoL of women with UI, with particular reference to social effects.47 It has since been validated in women and men with OAB, but only in those whose symptoms include UI.48 It has over 30 linguistic validations, which have made it ideal for assessment in multinational studies, and has been used in numerous clinical trials for OAB. The KHQ was originally tested in 293 women with UI and the results showed a greater impact on QoL in patients with OAB than in patients with stress UI or normal urodynamic function.47 The KHQ has been incorporated into the ICI Modular Questionnaire (ICIQ) as the ICIQ-LUTSqol.45

The Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (BFLUTS) questionnaire was developed to assess female LUTS, with an emphasis on quantifying the frequency and extent of UI.49 This 33-item questionnaire screens patients for LUTS and obtains a brief yet comprehensive summary of the level and impact of urinary symptoms. The BFLUTS has been incorporated into the ICI Modular Questionnaire (ICIQ) as the ICIQ-FLUTS and has been used, together with the ICSmale,50 to derive the ICIQ-OAB.45

Other questionnaires have been validated and are highly recommended, such as the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) and its short-version (UDI-6), the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) and its short-form (IIQ-7),51 and the Incontinence QoL Questionnaire (I-QOL).52 The I-QOL consists of 22 items and was designed as a QoL measure for people experiencing UI with particular reference to emotions and feelings; it has been incorporated into the ICI Modular Questionnaire (ICIQ) as the ICIQ-UIqol.45 Additionally, in order to assess the severity of urgency, some severity scale and single-item summary questionnaires have been developed, such as the Urgency Perception Scale (UPS) and the Patient Perception of Bladder Condition (PPBC).44,53,54

Economic burden

The economic burden of an illness is the total value of all resources used or lost by society as a result of illness.55 Cost of illness (COI) is the most frequently used descriptive methodology to estimate the economic burden of a disease, and it considers three types of costs: 1) direct, 2) indirect, and 3) intangible.56 Direct medical and nonmedical costs include the cost of diagnostic testing and visits to a healthcare provider, pharmacologic and other treatments, routine care, travel expenses related to treatments.57 Indirect costs can be substantial, including caregiver wages and worker productivity losses resulting either from disability or absenteeism due to illness, time loss (because of physician visits, diagnostic procedures, treatment sessions and follow-up consultations), and costs of OAB-related consequences (the so-called “consequence costs”) such as falls, fractures, urinary tract infections, skin ulcerations (in patients with UI), perineal trauma, and psychological consequences such as isolation and depression.9,57–61 Finally, intangible costs include the QoL impact and psychological burden which are difficult to measure and are usually excluded for COI analyses.57

Several COI studies have estimated the economic burden of UI, one of the main symptom of OAB, demonstrating its substantial economic impact on society.55,62–65 All these studies have used the ‘top-down’ approach that involves enumerated all costs for a typical person with UI, which then are combined with epidemiological data to provide annualized costs for a given population.

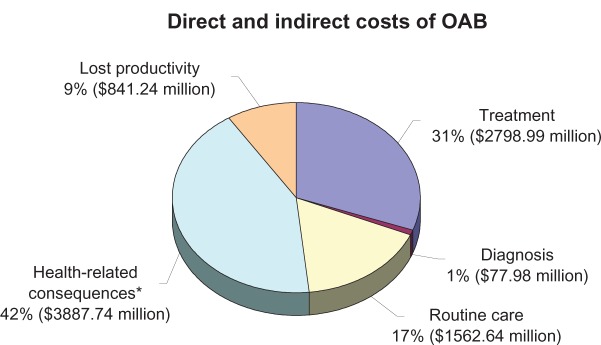

According to Hu et al,65 the overall cost associated with OAB was greater than $9 billion (2000 US$), including $78 million for diagnosis and $2.79 billion for treatment, to be added to consequence costs, such as of $1.56 billion for routine care (which includes the costs of incontinence supplies), $3.88 billion for health-related consequences, and to $841 million in lost productivity at work (Figure 2). Given that most people with UI or OAB do not seek medical treatment,3,7,10,11,66 it is not surprising that diagnosing was the smallest direct cost and self-management was a very large cost. If the estimated $2.9 billion for the institutional cost of OAB were added, the total cost for OAB was > $12 billion annually in the US.67 Thus, the total costs for OAB were of the same magnitude as those for breast cancer ($12.7 billion) and the treatment costs for osteoporosis ($13.8 billion);68 however, major costs related to OAB consequences could be likely diminished with diagnosis and treatment of the syndrome at an early stage.

Figure 2.

The overall estimated annual costs ($9 billion – 2000 US$) associated with OAB for patients in the community setting of United States. *Includes UTI, falls, broken bones, additional nursing home admissions, longer hospital stays, and skin conditions. Drawn from data of Hu et al.65

Two recent pieces of research evaluated the economic burden of OAB using the current ICS definitions.69,70 Onukwuga et al69 calculated the disease-specific total cost of OAB among community-dwelling adults in the US using prevalence estimated from the EpiLUTS survey. In the internet interview, participants were asked to answer to a question (UQ) about urgency on a Likert scale (‘Never/Rarely/Sometimes/Often/Almost always’) and to a question (UUIQ) about UUI (‘yes/no’). The societal cost of OAB totalled $24.9 billion per year (2007 US$) for OAB with UUI or at least ‘often’ urgency (42.2 million adults with OAB), and totalled $36.5 billion for OAB with UUI or at least ‘sometimes’ urgency (65.1 million adults with OAB). If institutional costs were included, this figure would be even higher. The economic burden of OAB differed by age groups. For instance, the costs of managing OAB symptoms were 2.5 times as high among adults younger than 65 years of age compared with adults 65 years or older for OAB with UUI or at least ‘often’ urgency. Differential economic burden across demographic groups are interesting because can be used to guide the development of treatment and program interventions designed to improve the management of OAB symptoms. Of note, variation in prevalence estimates was shown in the sensitivity analyses to have the largest impact on the COI estimate.69

Irwin et al70 calculated up-to-date estimates of the economic impact of OAB, with and without UUI, on the health sector of 6 countries (Canada, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the UK). Prevalence data was derived from the EPIC study.8 The total economic impact on health and social service systems of these 6 countries was calculated by multiplying the estimated number of people with OAB by the estimated cost per person. Separate analyses were run for direct and indirect costs. This study showed an estimated annual total costs of OAB in 6 countries (about 25 million OAB patients) to be €9.7 billion. Sensitivity analysis revealed that costs related to medical visits and treatment exerted the most effect on the total direct costs. Difference in OAB-related costs may vary substantially between countries as do country practice for frequency of visits and treatment patterns.70

Management and economics of interventions

Therapy options

An effective treatment of OAB represents the key in order to reduce both the symptom burden and the consequent QoL and socioeconomic impact. Current management options for OAB are designed to facilitate bladder filling/urine storage by decreasing detrusor contractility, increasing bladder capacity, or decreasing sensation.71,72 Behavioral interventions are simple and inexpensive and encompass bladder retraining, fluid scheduling, dietary modifications, pelvic floor exercises, and the optimized management of comorbid conditions;73–76 biofeedback and/or electrical stimulation are adjunctive measures that enable patients to locate and utilize their pelvic floor in an effective manner.74,75

Although there are several promising compounds in the drug pipeline,77 antimuscarinic drugs still represent the mainstay of pharmacological management of OAB.72,78–80 Tolterodine and oxybutynin are the two most frequently used drugs. Both were launched as immediate-release (IR) and, more recently, as extended release (XL) formulations.72,79,80 Although the efficacy of oxybutynin has been well documented in clinical trials, it is associated to troublesome side effects in approximately 50% to 70% of patients causing low persistence rate.68 A transdermal patch for oxybutynin is also available, which has been shown to be as effective as oxybutynin IR but with much better tolerability.72,82 As for efficacy, tolterodine is comparable to oxybutynin but in a head-to-head studies it showed fewer side effects and a lower discontinuation rate.83–86 More recently, in order to further reduce side effects, new antimuscarinics have emerged on the market, such as solifenacin, darifenacin and fesoterodine.87–90

In the past, surgical treatments with augmentation cystoplasty or conduit diversion were the only alternative in antimuscarinics-refractory patients. Nowadays, novel treatment strategies are available. There are many reports demonstrating the efficacy and safety of botulinum neurotoxin (BTX) type A and B in OAB (both neurogenic and idiopathic) but only few are randomized, placebo-controlled studies.91–93 Although these studies suggest an important role for intravesical BTX for OAB patients who fail other therapies, one has to be aware that this use remains off-label and based on limited clinical trials and little knowledge on the mechanism of action, long-term effects of chronic treatment, optimal dosing regimes, and sites of injection.77,94

Electromotive drug administration (EMDA) combines iontophoresis and electrophoresis for targeted delivery of drugs to deep tissue layers by means of an electrical field created between electrodes.95 It has been shown to be effective in patients diagnosed with OAB using lidocaine and dexamethasone as instilled drugs; however investigations of a larger group of patients are needed to provide sufficient evidence for the effectiveness of EMDA.96

Sacral neuromodulation (SNM) implies direct electrical stimulation of the sacral nerve roots with an implantable stimulator. SNM with InterStim therapy (Medtronic) has proven to be efficacious in more than 75% of patients with severe UUI, significantly improving HRQL,97,98 although complications, explantation and revision rates are not negligible.99

Health technology assessment and cost-effectiveness analysis

The use of economic evaluation of novel therapies to aid health decision-making, especially health priority setting and health resources allocation, has become widespread and represents a very important component of HTA. HTA is a multidisciplinary activity that systematically examines the safety, clinical efficacy and effectiveness, cost, cost-effectiveness, organizational implications, social consequences, legal and ethical considerations of the application of a health technology.100,101 HTA focuses on ‘the value’ (clinical and economic) of the technology relative to current (or best) clinical practice, assessing clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Randomized control trials are the best methodology to assess clinical effectiveness. On the contrary, in order to evaluate the economic impact of interventions, COI studies such as the aforementioned economic studies on UI and OAB,55,62–64,67,69,70 have been criticized because they are: 1) sensitive to some input parameters (eg, disease prevalence), 2) often not transparent, and 3) not designed to help allocate resources. COI methodology does not value outcomes and, therefore, it should not be used for allocating resources, although often it is used in this manner. Just because the economic cost of depression was $83.1 billion (2000 US$)102 does not mean that we should direct nine times as much resources to depression than to OAB ($9 billion, 2000 US$).65 Furthermore, COI studies are heavily influenced by the context: the year of the costs, the perspective (patient, healthcare system, society) of the analysis, and the population under study. Hence, several other types of models have to be used, and cost-effectiveness (CEA), cost-utility (CUA), and cost-benefit analyses (CBA) are the most commonly accepted.

CEA compares a new technology with current practice to calculate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), defined as the difference in cost divided by the difference in effectiveness. CEA considers both the costs and outcomes of treatment and it allows making a balance between the incremental cost of a treatment and its effect.57 If the ‘price’ of the additional outcome obtained with the new treatment is low enough, the treatment is considered ‘cost-effective’.

CEA compares therapies in one disease area. However, with limited budgets, stakeholders have a difficult task of making decisions across disease areas. The solution comes in the form of CUA, which compares costs and improvements in QoL. CUA can be considered a special case of CEA, and the two terms are often used interchangeably. A CUA uses a global QoL outcome measure (utility) that allows the comparison of interventions of different diseases. QoL is an intangible cost and difficult to measure; however, it has been integrated into economic analysis in the form of a quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) model, the preferred measure for estimating the value of health state.95

Health utility measures

Among the most common methods of measuring health state value there are QALY and willingness-to-pay (WTP) approaches. QALYs are increasingly used in CUA as the current standard measure of effectiveness to allow comparisons across different health-care interventions for different medical conditions. The QALY is able to achieve this by capturing the impact of interventions on the length of life (in the form of ‘years’) and/or the quality of life (in the form of ‘health state values’) into a single summary measure, based on people’s preference. The number of QALYs gained by a treatment can then be incorporated with medical costs to arrive at a final common denominator of cost/QALYs.

Health state utility measures are an instrument that enables QoL changes induced by a particular state and by a medical therapy to be measured. Utility values also represent the strength of the preference that individuals or society have for a particular health outcome.103 These preferences are then used to value health states relative to one another. Utilities values range from 0.0 (death state) to 1.0 (perfect health state), a higher value indicating a better QoL of the individual. Utilities obtained from patient preferences, rather than from health care professionals, administrators or the general public, are by far the most valuable.104

Although usefulness of the QALY is still debated,105,106 the model is particularly important for diseases that have a major impact on QoL, such as UI and OAB.107–111 However, published data linking OAB with the utility scores are still limited.

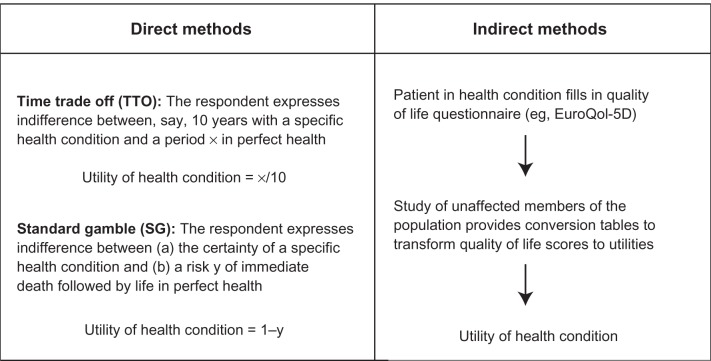

There are direct or indirect methods of health utility valuation (Figure 3). Most-used direct methods include trade-off (standard gamble [SG] and time trade-off [TTO]) and visual analog scale (VAS).103 The main indirect methods of utility measurement include generic preference instruments, condition-specific preference measures, and mapping from a condition-specific HRQL instrument to a generic instrument.40,57,103 Indirect methods are based on mapping preferences onto the utility scale indirectly via a HRQL questionnaire; these methods are less time consuming, based on simple and versatile questionnaires that stratify data into a number of different dimensions not registered by direct methods. There is, however, no universally accepted theoretical basis for choosing direct or indirect methods.112

Figure 3.

Direct versus indirect methods of utility elicitation. Reproduced from Arnold D, Girling A, Stevens A, Lilford R. Comparison of direct and indirect methods of estimating health state utilities for resource allocation: review and empirical analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2688.112 Copyright © 2009 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Generic preference-based utility instruments are increasingly being used in CUA of pharmaceutical and other health care interventions because they generate utilities that can be used to compare QALYs gained for interventions across patient groups and diseases. SF-6D and EQ5D are the most widely recognized and recommended generic instruments for quantifying utility and QoL among patients with UI and OAB.41 The SF-6D is a derivative of the SF-36.38,42,43 Whenever SF-36 raw scores are available, SF-6D utilities can be computed.113 The endpoints for the SF-6D are 1.00 and 0.30 for the worst possible health state. The EQ-5D is a six-item, standardized instrument developed by the EuroQol Group for use as a measure of health outcome and applicable to a wide range of health conditions and treatments. It provides a simple descriptive Profile and a single index value for health status.114,115 The EQ5Dindex ranges from 0 (a health state equivalent to death) to 1 (a perfect health state); it permits values worse than death. Currie et al,41 using the EQ-5D, reported that patients with stress UI had a lower mean (SD) EQ5Dindex compared with all other patients (P < 0.001); the EQ5Dindex changed from 0.564 (0.338), to 0.689 (0.277) and 0.746 (0.226) for stress UI, UI and continence, respectively. In the EPIC study, OAB patients reported slightly lower, but statistically significant, mean EQ-5D scores than controls (0.85 versus 0.90; P < 0.001).23 In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has specified the EQ-5D as its preferred method of utility measurement.101

Generic preference-based instruments have been criticized because, for some medical conditions, the generic dimensions may be considered to be irrelevant or insensitive in terms of capturing small but important clinical changes or indeed may miss important dimensions altogether.116,117 OAB is one such medical condition. Therefore, preference-based condition-specific measures, derived from condition-specific HRQL instruments, are beginning to be developed.118–121 As previously mentioned, many condition-specific HRQL questionnaires have been introduced to account for all OAB patients (wet and dry); however, none of the existing condition-specific measures for OAB is preference-based. The construction of preference-based, condition-specific instruments is promising, but their value for decision-making has yet to be realized.117,122 Yang et al117 aimed to estimate a preference-based single index for calculating QALYs for OAB patients, based on a valuation survey of the UK general population and using the five-dimensional health classification system OAB-5D, derived from the OAB-q. The study applied the methods originally developed in the SF-6D study.113 Based on the best model chosen by authors, a preference-based scoring algorithm can be established for calculating QALYs using OAB-q data. Studies like this may contribute toward extending the application of CUA in OAB, allowing the HTA of new interventions in OAB patients using existing and future OAB-q data sets.

The WTP approach is an alternative method to measure health state used in CBA (a type of CEA that attempts to measure benefits in money) and addressing both physical and psychological burden.40 Using this approach, a Swedish study administered questionnaires to 461 individuals with OAB, with either urge or mixed UI.42 The median and mean WTP for a 25% reduction in symptoms were SEK240 per month and SEK530 per month (1996 values), respectively. For a 50% reduction, both median and mean WTP doubled. A similar approach was used by O’Conor et al43 in US, with 495 questionnaires completed; the median and mean WTP for a 25% reduction in symptoms were $US27 and $US87 per month (1997 US$ values), respectively. Median and mean estimates nearly tripled for a 50% reduction. Capri et al123 measured the WTP for a reduction in urinary frequency and leakages by administrating a questionnaire to 388 Italian wet OAB patients. The mean WTP per month was 229.000 Italian line ($115, US$ 2000) for men and Lit 153.000 ($77) for women. The study concluded that patients with incontinence problems were willing to pay amounts that were higher than the cost of any drug therapy available for OAB.123

Economics of interventions

Published economic evaluations of treatments for OAB have focused almost entirely on pharmacological treatments, and mainly on the two most commonly used drugs, oxybutynin and tolterodine.84,107,111,124–128

In a systematic review of these published economic researches, evaluations comparing drug therapy with no treatment have concluded that drug therapy is cost effective.129 Results of analyses comparing the formulations of oxybutynin and tolterodine are somewhat conflicting, largely due to the data sources employed for effectiveness and treatment discontinuation rates.129

Kobelt et al107 in a placebo-controlled clinical trial to evaluate treatment with tolterodine IR over 1 year indicated that tolterodine would lead to an average QALYs gain of 0.025 per year, at an incremental cost of SEK5,309 (1997 values, $US1 = 0.81 = SEK7.40), or SEK213,000 per QALY gained. The authors concluded that treatment with tolterodine IR was cost-effective, given that the cost per QALY estimate fell within ratios largely accepted to be cost-effective.107

In the OBJECT trial comparing oxybutynin XL and tolterodine IR, the estimated difference in QALYs at the end of 1 year was only 0.004.84 Using data derived from this trial together with data from the literature, Getsios et al125 developed a Markov model to compare health-economic outcomes for the new oxybutynin XL and tolterodine IR. Costs after 1 year were estimated to be an average of $32 (2002 Canadian dollars) less per patient for oxybutynin XL compared with tolterodine IR. Patients receiving oxybutynin XL were expected to have a mean 16.5 additional incontinence-free days compared with those receiving tolterodine IR. The results of these analyses suggest that when priced equivalently, oxybutynin XL would reduce costs and provide better results than tolterodine IR.125 These findings are in agreement with that of Guest et al,128 which reported that starting OAB treatment with XL oxybutynin is expected to be clinically more effective and potentially more cost-effective than starting with either IR oxybutynin or tolterodine.

Hughes et al124 constructed an empirical models of drug effects (number of incontinent-free weeks) and persistence (proportion of patients still on therapy) in order to determine clinical effectiveness which was combined with direct medical costs to calculate cost-effectiveness of IR and XL formulations of oxybutynin and tolterodine from the perspective of the NHS. A systematic review that identified appropriate randomized clinical trials provided evidence on efficacy. Oxybutynin IR was the least expensive (£40/patient/year, 2001 values), followed by tolterodine XL (£64/patient/year), tolterodine IR (£74/patient/year) and oxybutynin XL (£79/patient/year). Incontinence-free weeks per patient per year were highest with oxybutynin XL (11.1), followed by tolterodine XL (10.9), tolterodine IR (9.6) and oxybutynin IR (7.6). Tolterodine IR did not appear to be a cost-effective option as it was less effective and more costly than the XL formulations.124

Some recent studies evaluated the pharmacoeconomics of the new antimuscarinics. In the CUA of Speakman et al,110 flexible dosing with solifenacin (5 mg and 10 mg) was a less costly and more effective treatment strategy compared with tolterodine (IR 2 mg bd/XL 4 mg). During the course of 1 year, the estimated cost per patient was £509 for patients treated with solifenacin and £526 for those given tolterodine, a cost saving of £17 per patient. Treatment with solifenacin was also associated with a small incremental gain of 0.004 QALYs over tolterodine.110 These results are consistent with that of other studies.108,130 Comparing the cost-effectiveness of eight antimuscarinic agents, Ko et al130 found that solifenacin 5 mg had the lowest costs and highest effectiveness in the treatment of OAB.

Patients nonadherence with medication represents one of the main challenge to improving OAB symptom burden. Kelleher et al47 described in their study that 82% of patients treated with antimuscarinics discontinued treatment within 6 months. In the study by Pelletier et al,131 few patients achieving a PDC (proportion of days covered) of 80% or higher. Interestingly, total costs were higher among pharmacologically treated OAB patients due to higher pharmacy costs, but outpatient and inpatient costs were higher among nonpharmacologically managed patients.131

Few authors tried a health economic evaluation of intradetrusorial BTX.132–134 By calculating the minimum increase in utility score needed to obtain a ICER of < £20,000 to £30,000/QALY (generally viewed as cost-effective by NICE)135 and by comparing this to utility scores associated with OAB symptoms calculated in studies with anticholinergics,111 Kalsi et al133 found that BTX A is likely to be a highly cost-effective treatment of OAB symptoms, at £6,000 per QALY gained relative to standard care. Wu et al134 assessed the cost-effectiveness in QALYs of BTX A injection compared to anticholinergic medications for the treatment of idiopathic UUI. The analysis was conducted from a societal perspective with a 2-year time frame using 3-month cycles. While BTX was more expensive ($4,392 vs $2,563; 2008 US$) it was also more effective (1.63 vs 1.50 QALY) compared to the anticholinergic regimen. The calculated ICER was $14,377 per QALY, meaning that BTX is cost-effective compared to anticholinergics. In sensitivity analyses, anticholinergics become cost-effective only if compliance exceeds 75% (33% in the base case) and if the BTX procedure cost exceeds $3,875 ($1,690 in the base case).134

Aboseif et al136 performed a retrospective cost analysis of 55 patients (82% with OAB symptoms) receiving SNM with InterStim system (Medtronic). Health care utilization, drug use and costs were determined for the year before and the year after implantation. The treatment reveals to be subjectively and objectively effective, and resulted in a 92% reduction in outpatient visits, diagnostic and procedure costs along with a 30% reduction in drug expenditures. The authors concluded that SNM allows a significant reduction in health care costs in patients with refractory LUTS.136

Conclusions

The prevalence of OAB is high, although underestimated, and will continue to grow as the average age of the population increases. Large amounts of data have been accumulated demonstrating the tremendous impact of the syndrome on all aspects of the patient’s QoL.

COI analyses have shown that OAB and the accompanying UUI are a heavy financial burden to the patient, the healthcare national systems and society, although a more detailed knowledge of OAB-related total economic costs requires further studies. Interestingly, the ‘consequence costs’, as well as the cost of lost productivity, are major costs of OAB which could conceivably be diminished with diagnosis and treatment of the disorder at an early stage.67

Many treatment options for OAB have been introduced, but as new treatments and technologies become available, it will be important to weigh the additional costs and the added benefits in order to guide decisions about allocation of limited resources. CUA with QALYs still represents the most widely accepted cost and outcome method to measures the value (improvement in quality and length of life) conferred by an intervention, allowing the creation of a value-based medicine incorporating QoL parameters that simple evidence-based outcomes usually ignore.137 Health utilities allow a measurement of QoL and its integration in the economic evaluation. The development of suitable instruments for quantifying utility among OAB patients is vitally important to extend the application of CUA in OAB and to ensure an appropriate allocation of healthcare resources for this disorder.

Antimuscarinic drugs still represent the mainstay of OAB treatment and published CUAs showed their cost-effectiveness. However, patient nonadherence with medications is still a serious problem which, together with underdiagnosis and undertreatment, represent central challenges to reduce OAB socioeconomic burden. According to Schabert et al,138 a combination of educational and behavioral interventions, together with optimization of pharmacotherapeutic regimens, will be necessary to improve compliance with long-term therapy. Further studies are needed to define the role and cost-effectiveness of the other pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment strategies for OAB.

Figure 4.

Heath-related utility scores based on the mean EQ5Dindex, in a patients population with OAB symptoms and continence/incontinence/stress incontinence. Reproduced with permission from Currie CJ, Mcewan P, Poole CD, Odeyemi IA, Datta SN, Morgan CL. The impact of the overactive bladder on health-related utility and quality of life. BJU Int. 2006;97:1267–1272.41 Copyright © 2006 Wiley-Blackwell.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BTX

botulinum neurotoxin

- CBA

cost-benefit analysis

- CEA

cost-effectiveness analysis

- COI

cost of illness

- CUA

cost-utility analysis

- ED

erectile dysfunction

- EMDA

electromotive drug administration

- HRQL

health-related quality of life

- HTA

Health Technology Assessment

- ICER

incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- ICI

International Consultation on Incontinence

- ICS

International Continence Society

- IR

immediate-release

- LUTS

lower urinary tract symptoms

- NHS

National Health Service

- NICE

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

- NOBLE

National Overactive Bladder Evaluation program

- OAB

overactive bladder syndrome

- OAB-q

overactive bladder quality of life questionnaire

- QALYs

quality-adjusted life years

- QoL

quality of life

- SNM

sacral neuromodulation

- UI

urinary incontinence

- UUI

urge urinary incontinence

- WPAI

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment instrument

- WTP

willingness-to-pay

- XL

extended release

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–178. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu FM, Dmochowski R. Pathophysiology of overactive bladder. Am J Med. 2006;119(3 Suppl 1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milsom I, Abrams P, Cardozo L, et al. How widespread are the symptoms of an overactive bladder and how are they managed? A population-based prevalence study. BJU Int. 2001;87:760–766. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW, et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J Urol. 2003;20:327–336. doi: 10.1007/s00345-002-0301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tubaro A, Palleschi G. Overactive bladder: epidemiology and social impact. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17:507–511. doi: 10.1097/01.gco.0000183529.26352.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serels S. The wet patient: understanding patients with overactive bladder and incontinence. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:791–801. doi: 10.1185/030079904125003593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ricci JA, Baggish JS, Hunt TL, et al. Coping strategies and health care-seeking behavior in a US national sample of adults with symptoms suggestive of overactive bladder. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1245–1259. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in 5 countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1306–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown JS, McGhan WF, Chokroverty S. Comorbidities associated with overactive bladder. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:S574–S579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norton PA, MacDonald LD, Sedgwick PM, Stanton SL. Distress and delay associated with urinary incontinence, frequency, and urgency in women. BMJ. 1988;297:1187–1189. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6657.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrams P, Kelleher CJ, Kerr LA, Rogers RG. Overactive bladder significantly affects quality of life. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6(11 Suppl):S580–S590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johannesson M, O’Conor RM, Kobelt-Nguyen G, Mattiasson A. Willingness to pay for reduced incontinence symptoms. Br J Urol. 1997;80:557–562. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lenderking WR, Nackley JF, Anderson RB, et al. A review of the quality-of-life aspects of urinary urge incontinence. Pharmacoeconomics. 1996;9:11–23. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199609010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irwin DE, Milsom I, Kopp Z, Abrams P, Cardozo L. Impact of overactive bladder symptoms on employment, social interactions and emotional well-being in six European countries. BJU Int. 2006;97:96–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darkow T, Fontes CL, Williamson TE. Costs associated with the management of overactive bladder and related comorbidities. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:511–519. doi: 10.1592/phco.25.4.511.61033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zorn BH, Montgomery H, Pieper K, et al. Urinary incontinence and depression. J Urol. 1999;162:82–84. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199907000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown JS, Subak LL, Gras J, et al. Urge incontinence: The patient’s perspective. J Women’s Health. 1998;7:1263–1269. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart W, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff G, et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive in the United States. World J Urol. 2003;20:327–336. doi: 10.1007/s00345-002-0301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson D, Pearce KF, Preisser JS, et al. Relationship between patient reports of urinary incontinence symptoms and quality of life measures. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:224–228. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liberman JN, Hunt TL, Stewart WF, et al. Health-related quality of life among adults with symptoms of overactive bladder: results from a US community-based survey. Urology. 2001;57:1044–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)00986-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michel MC, de la Rosette JJ, Piro M, Schneider T. Comparison of symptom severity and treatment response in patients with incontinent and continent overactive bladder. Eur Urol. 2005;48:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coyne KS, Payne C, Bhattacharyya SK, et al. The impact of urinary urgency and frequency on health-related quality of life in overactive bladder: results from a national community survey. Value Health. 2004;7:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.74008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, et al. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008;101:1388–1395. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponholzer A, Temml C, Obermayr R, et al. Association between lower urinary tract symptoms and erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2004;64:772–776. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frankel SJ, Donovan JL, Peters TI, et al. Sexual dysfunction in men with lower urinary tract symptoms. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:677–685. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irwin DE, Milsom I, Reilly K, et al. Overactive bladder is associated with erectile dysfunction and reduced sexual quality of life in men. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2904–2910. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aslan G, Cavus E, Karas H, Oner O, Duran F, Esen A. Association between lower urinary tract symptoms and erectile dysfunction. Arch Androl. 2006;52:155–162. doi: 10.1080/01485010500379871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coyne KS, Margolis MK, Jumadilova Z, Bavendam T, Mueller E, Rogers R. Overactive bladder and women’s sexual health: what is the impact? J Sex Med. 2007;4:656–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yip SK, Chan A, Pang S, et al. The impact of urodynamic stress incontinence and detrusor overactivity on marital relationship and sexual function. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1244–1248. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen BL, Barboglio P, Gousse A. The impact of lower urinary tract symptoms and urinary incontinence on female sexual dysfunction using a validated instrument. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1418–1423. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Irwin DE, Milsom I, Reilly K, et al. Overactive bladder symptoms associated with a negative impact on work productivity: results from the EPIC study International Continence Society; Christchurch, New Zealand: 2006URL: http://www.icsoffice.org/publications/2006/pdf/0432.pdfAccessed Jul 15, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sexton CC, Coyne KS, Vats V, et al. Impact of overactive bladder on work productivity in the United States: results from EpiLUTS. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(4 Suppl):S98–S107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353–365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coyne KS, Matza LS, Brewster-Jordan J. “We have to stop again?!”: The impact of overactive bladder on family members. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28:969–975. doi: 10.1002/nau.20705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coyne KS, Matza LS, Brewster-Jordan J, Thompson C, Bavendam T. The psychometric validation of the OAB family impact measure (OAB-FIM) Neurourol Urodynam. 2009 doi: 10.1002/nau.20715. [Epub Mar 9] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basra R, Kelleher C. Disease burden of overactive bladder: quality-of-life data assessed using ICI-recommended instruments. Pharmacoeconomic. 2007;25:129–142. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donovan J, Badia X, Corcos J, et al. Committee 6: symptom and quality of life assessment. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, et al., editors. Incontinence. Plymouth, United Kingdom: Plymbridge Distributors, Ltd; 2002. pp. 267–316. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jenkinson C, Stewart-Brown S, Petersen S, Paice C. Assessment of the SF-36 version 2 in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:46–50. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Komaroff AL, Fagioli LR, Doolittle TH, et al. Health status in patients with chronic fatigue Syndrome and in general population and disease comparison groups. Am J Med. 1996;101:281–290. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(96)00174-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobelt G. Economic consideration and outcome measurement in urge incontinence. J Urol. 1997;50(Suppl 6A):100–107. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00602-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Currie CJ, McEwan P, Poole CD, Odeyemi IA, Datta SN, Morgan CL. The impact of the overactive bladder on health-related utility and quality of life. BJU Int. 2006;97:1267–1272. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johannesson M, O’Conor RM, Kobelt-Nguyen G, Mattiasson A. Willingness to pay for reduced incontinence symptoms. Br J Urol. 1997;80:557–562. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Conor RM, Johannesson M, Hass SL, Kobelt-Nguyen G. Urge incontinence. Quality of life and patients’ valuation of symptom reduction. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;14:531–539. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199814050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coyne K, Revicki D, Hunt T, et al. Psychometric validation of an overactive bladder symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire: the OAB-q. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:563–574. doi: 10.1023/a:1016370925601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abrams P, Avery K, Gardener N, et al. The International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire: www.iciq.net. J Urol. 2006;175:1063–1066. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coyne KS, Matza LS, Thompson CL. The responsiveness of the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire (OAB-q) Qual Life Res. 2005;14:849–855. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0706-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kelleher CJ, Cardozo LD, Khullar V, Salvatore S. A medium-term analysis of the subjective efficacy of treatment for women with detrusor instability and low bladder compliance. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:988–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb12054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reese PR, Pleil AM, Okano GJ, et al. Multinational study of reliability and validity of the King’s Health Questionnaire in patients with overactive bladder. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:427–442. doi: 10.1023/a:1023422208910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson S, Donovan J, Brookes S, Eckford S, Swithinbank L, Abrams P. The Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms questionnaire: development and psychometric testing. BJU. 1996;77:805–812. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Donovan J, Abrams P, Peters T, et al. The ICS-‘BPH’ study: the psychometric validity and reliability of the ICSmale questionnaire. BJU. 1996;77:554–562. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.93013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shumaker SA, Wyman JF, Uebersax JS, et al. Health-related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Continence Program in Women (CPW) Research Group. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:291–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00451721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagner TH, Patrick DL, Bavendam TG, Martin ML, Buesching DP. Quality of life of persons with urinary incontinence: development of a new measure. Urology. 1996;47:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matza LS, Thompson CL, Krasnow J, Brewster-Jordan J, Zyczynski T, Coyne KS. Test-retest reliability of four questionnaires for patients with overactive bladder: the overactive bladder questionnaire (OAB-q), patient perception of bladder condition (PPBC), urgency questionnaire (UQ), and the primary OAB symptom questionnaire (POSQ) Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:215–225. doi: 10.1002/nau.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matza LS, Zyczynski TM, Bavendam T. A review of quality-of-life questionnaires for urinary incontinence and overactive bladder: which ones to use and why? Curr Urol Rep. 2004;5:336–342. doi: 10.1007/s11934-004-0079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wagner TH, Hu TW. Economic costs of urinary incontinence in 1995. Urology. 1998;51:355–361. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00623-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akobundu E, Ju J, Blatt L, Mullins CD. Cost-of-illness studies : a review of current methods. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24:869–890. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200624090-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu TW, Wagner TH. Economic considerations in overactive bladder. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6(11 Suppl):S591–S598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Erdem N, Chu FM. Management of overactive bladder and urge urinary incontinence in the elderly patient. Am J Med. 2006;119(3 Suppl 1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wagg AS, Cardozo L, Chapple C, et al. Overactive bladder syndrome in older people. BJU Int. 2007;99(3):502–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu EQ, Birnbaum H, Marynchenko M, Mareva M, Williamson T, Mallett D. Employees with overactive bladder: work loss burden. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47:439–446. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000161744.21780.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brubaker L, Chapple C, Coyne KS, Kopp Z. Patient-reported outcomes in overactive bladder: importance for determining clinical effectiveness of treatment. Urology. 2006;68(2 Suppl):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilson L, Brown JS, Shin GP, Luc KO, Subak LL. Annual direct cost of urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:398–406. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01464-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hu TW, Wagner TH, Bentkover JD, Leblanc K, Zhou SZ, Hunt T. Costs of urinary incontinence and overactive bladder in the United States; a comparative study. Urology. 2004;63:461–465. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hu TW. Impact of urinary incontinence on health-care costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:292–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hu TW, Wagner TH, Bentkover JD, et al. Estimated economic costs of overactive bladder in the United States. Urology. 2003;61:1123–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.MacKay K, Hemmett L. Needs assessment of women with urinary incontinence in a district health authority. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:801–804. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu TW, Wagner TH. Health-related consequences of overactive bladder: an economic perspective. BJU Int. 2005;96(Suppl 1):43–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.National Institutes of Health Disease-Specific Estimates of Direct and Indirect Costs of Illness and NIH Support Bethesda, Maryland: US Public Health Services; 2000URL: http://ospp.od.nih.gov/ecostudies/COIreportweb.htmAccessed Jul 15, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Onukwugha E, Zuckerman IH, McNally D, Coyne KS, Vats V, Mullins CD. The total economic burden of overactive bladder in the United States: a disease-specific approach. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(4 Suppl):S90–S97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Irwin DE, Mungapen L, Milsom I, Kopp Z, Reeves P, Kelleher C. The economic impact of overactive bladder syndrome in six Western countries. BJU Int. 2009;103:202–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cartwright R, Renganathan A, Cardozo L. Current management of overactive bladder. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20:489–495. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32830fe38c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ouslander JG. Management of overactive bladder. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:786–799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bo K, Berghmans LC. Nonpharmacologic treatments for overactive bladder-pelvic floor exercises. Urology. 2000;55:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brubaker L. Electrical stimulation in overactive bladder. Urology. 2000;55:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00488-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cardozo LD. Biofeedback in overactive bladder. Urology. 2000;55:24–28. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00489-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Payne CK. Behavioral therapy for overactive bladder. Urology. 2000;55:3–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00484-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sacco E, Pinto F, Bassi P. Emerging pharmacological targets in overactive bladder therapy: experimental and clinical evidences. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(4):583–598. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0529-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Andersson KE. New pharmacologic targets for the treatment of the overactive bladder: an update. Urology. 2004;63(Suppl 3A):32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Appell RA. The newer antimuscarinic drugs: bladder control with less dry mouth. Cleve Clin J Med. 2002;69:761–769. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.69.10.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cannon TW, Chancellor MB. Pharmacotherapy of the overactive bladder and advances in drug delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:205–217. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200203000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Katz IR, Sands LP, Bilker W, et al. Identification of medications that cause cognitive impairment in older people: The case of oxybutynin chloride. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hashim H, Abrams P. Drug treatment of overactive bladder: efficacy, cost and quality-of-life considerations. Drugs. 2004;64:1643–1656. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Drutz H, Appell RA, Gleason D, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of tolterodine compared to oxybutynin and placebo in patients with overactive bladder. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 1999;10:283–289. doi: 10.1007/s001929970003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Appell RA, Sand P, Dmochowski R, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial of extended-release oxybutynin chloride and tolterodine tartrate in the treatment of overactive bladder: results of the OBJECT study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:358–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Diokno AC, Appell RA, Sand PK, et al. Prospective, randomized, doubleblind study of the efficacy and tolerability of the extended-release formulations of oxybutynin and tolterodine for overactive bladder: results of the OPERA trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:687–695. doi: 10.4065/78.6.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sussman G, Garely A. Treatment of overactive bladder with oncedaily extended-release tolterodine or oxybutynin: the Antimuscarinic Clinical Effectiveness Trial (ACET) Curr Med Res Opin. 2002;19:177–184. doi: 10.1185/030079902125000570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Haab F, Cardozo L, Chapple C, et al. Long-term open-label solifenacin treatment associated with persistence with therapy in patients with overactive bladder syndrome. Eur Urol. 2005;47:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chapple CR, Martinez-Garcia R, Selvaggi L, et al. A comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of solifenacin succinate and extended release tolterodine at treating overactive bladder syndrome: Results of the STAR trial. Eur Urol. 2005;48:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Steers W, Corcos J, Foote J, Kralidis G. An investigation of dose titration with darifenacin, an M3-selective receptor antagonist. BJU Int. 2005;95:580–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Michel MC. Fesoterodine: a novel muscarinic receptor antagonist for the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:1787–1796. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.10.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schurch B, de Seze M, Denys P, et al. Botulinum toxin type a is a safe and effective treatment for neurogenic urinary incontinence: Results of a single treatment, randomized, placebo controlled 6-month study. J Urol. 2005;174:196–200. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000162035.73977.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sahai A, Khan MS, Dasgupta P. Efficacy of botulinum toxin-A for treating idiopathic detrusor overactivity: results from a single center, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Urol. 2007;177:2231–2236. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ghei M, Maraj BH, Miller R, et al. Effects of botulinumtoxin B on refractory detrusor overactivity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, crossover trial. J Urol. 2005;174:1873–1877. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000177477.83991.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sacco E, Paolillo M, Totaro A, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of overactive bladder. Urologia. 2008;75:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Di Stasi SM, Giannantoni A, Vespasiani G, Navarra P, Capelli G, Massoud R, et al. Intravesical electromotive administration of oxybutynin in patients with detrusor hyperreflexia unresponsive to standard anticholinergic regimens. J Urol. 2001;165:491–498. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200102000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gauruder-Burmester A, Biskupskie A, Rosahl A, Tunn R. Electromotive Drug Administration for Treatment of Therapy-Refractory Overactive Bladder. Int Braz J Urol. 2008;34:758–764. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382008000600011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Janknegt RA, Hassouna MM, Siegel SW, et al. Long-term effectiveness of sacral nerve stimulation for refractory urge incontinence. Eur Urol. 2001;39:101–106. doi: 10.1159/000052420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Das AK, Carlson AM, Hull M. Improvement in depression and health-related quality of life after sacral nerve stimulation therapy for treatment of voiding dysfunction. Urology. 2004;64:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hijaz A, Vasavada S. Complications and troubleshooting of sacral neuromodulation therapy. Urol Clin North Am. 2005;32:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Busse R, Orvain J, Velasco M, et al. Best practice in undertaking and reporting health technology assessments. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2002;18:361–422. doi: 10.1017/s0266462302000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.National Institute for Clinical Excellence Guide to the methods of technology appraisal NICE; 2004URL: http://www.nice.org.uk/niceMedia/pdf/TAP_Methods.pdfAccessed Jul 15, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 102.Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1465–1475. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Torrance GW. Measurement of health state utilities for economic appraisal: a review. J Health Econom. 1986;5:1–30. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(86)90020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rodriguez LV, Blander DS, Dorey F, Raz S, Zimmern P. Discrepancy in patient and physician perception of patient’s quality of life related to urinary symptoms. Urology. 2003;62:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Prieto LS. Problems and solutions in calculating quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2003;1:80. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mortimer D, Segal L. Comparing the incomparable? a systematic review of competing techniques for converting descriptive measures of health status into QALY-weights. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:66–89. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07309642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kobelt G, Jönsson L, Mattiasson A. Cost-effectiveness of new treatments for overactive bladder: the example of tolterodine, a new muscarinic agent: a Markov model. Neurourol Urodyn. 1998;17:599–611. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(1998)17:6<599::aid-nau4>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Milsom I, Axelsen S, Kulseng-Hansen S, Mattiasson A, Nilsson CG, Wickstrøm J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of solifenacin flexible dosing in patients with overactive bladder symptoms in four Nordic countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:693–699. doi: 10.1080/00016340902849738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wu JM, Siddiqui NY, Amundsen CL, Myers ER, Havrilesky LJ, Visco AG. Cost-effectiveness of botulinum toxin a versus anticholin-ergic medications for idiopathic urge incontinence. J Urol. 2009;181:2181–2186. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Speakman M, Khullar V, Mundy A, Odeyemi I, Bolodeoku J. A cost-utility analysis of once daily solifenacin compared to tolterodine in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:2173–2179. doi: 10.1185/03007990802234829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.O’Brien BJ, Goeree R, Bernard L, Rosner A, Williamson T. Cost-Effectiveness of tolterodine for patients with urge incontinence who discontinue initial therapy with oxybutynin: a Canadian perspective. Clin Ther. 2001;23:2038–2049. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Arnold D, Girling A, Stevens A, Lilford R. Comparison of direct and indirect methods of estimating health state utilities for resource allocation: review and empirical analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2688. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a utility based algorithm from the SF-36 Health Survey. J Health Econ. 2002;21:271–292. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.EuroQoL Group URL: http://www.euroqol.org/home.htmlAccessed Jul 15, 2009

- 115.EuroQoL Group EuroQoL – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Brazier J, Deverill M, Green C, et al. A review of the use of health status measures in economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3:1–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yang Y, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, Coyne Karin P. Estimating a Preference-Based Single Index from the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire. Value Health. 2009;12:159–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kok ET, McDonnell J, Stolk EA, Stoevelaar HJ, Busschbach JJ. The valuation of the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) for use in economic evaluations. Eur Urol. 2002;42:491–497. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00403-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Stolk EA, Busschbach JJ. Validity and feasibility of the use of condition-specific outcome measures in economic evaluation. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:363–371. doi: 10.1023/a:1023453405252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Brazier JE, Czoski-Murray C, Roberts J, et al. Estimation of a preference-based index from a condition specific measure: the King’s Health Questionnaire. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:113–126. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07301820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Revicki DA, Leidy NK, Brennan F, et al. Development and preliminary validation of the multiattribute rhinitis symptom utility index. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:693–702. doi: 10.1023/a:1008860113818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dowie J. Decision validity should determine whether generic or condition-specific HRQOL measure is used in health care decisions. Health Econ. 2002;11:1–8. doi: 10.1002/hec.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Capri S, Sormani MP, Lavezzari M, Velona T. Willingness to pay for reduced urge incontinence. Value in Health. 2000;3:304–305. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hughes DA, Dubois D. Cost-effectiveness analysis of extended-release formulations of oxybutynin and tolterodine for the management of urge incontinence. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22:1047–1059. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Getsios D, Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, El-Hadi W, Payne K. Canadian economic comparison of extended-release oxybutynin and immediate-release tolterodine in the treatment of overactive bladder. Clin Ther. 2004;26:431–438. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Varadharajan S, Jumadilova Z, Girase P, Ollendorf DA. Economic impact of extended-release tolterodine versus immediate- and extended-release oxybutynin among commercially insured persons with overactive bladder. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(4 Suppl):S140–S149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Arikian SR, Casciano J, Doyle JJ, Tarride JE, Casciano RN. A pharmacoeconomic evaluation of two new products for the treatment of overactive bladder. Manag Care Interface. 2000;13:88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Guest JF, Abegunde D, Ruiz FJ. Cost effectiveness of controlledrelease oxybutynin compared with immediate-release oxybutynin and tolterodine in the treatment of overactive bladder in the UK, France and Austria. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24:305–321. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200424060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Getsios D, El-Hadi W, Caro I, Caro JJ. Pharmacological management of overactive bladder: a systematic and critical review of published economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:995–1006. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ko Y, Malone DC, Armstrong EP. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of antimuscarinic agents for the treatment of overactive bladder. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1694–1702. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.12.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pelletier EM, Vats V, Clemens JQ. Pharmacotherapy adherence and costs versus nonpharmacologic management in overactive bladder. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(4 Suppl):S108–S114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sangster P, Kalsi V. Health economics and intradetrusor injections of botulinum for the treatment of detrusor overactivity. BJU Int. 2008;102(Suppl 1):17–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kalsi V, Popat RB, Apostolidis A, et al. Cost-consequence analysis evaluating the use of botulinum neurotoxin-A in patients with detrusor overactivity based on clinical outcomes observed at a single UK centre. Eur Urol. 2005;49:519–527. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]