Abstract

20S-dihydroprotopanaxatriol (2H-PPT) is a derivative of protopanaxatrol from ginseng. Unlike other components from Panax ginseng, the pharmacological activity of this compound has not been fully elucidated. In this study, we investigated the modulatory activity of 2H-PPT on the cellular responses of monocytes and macrophages to understand its immunoregulatory actions. 2H-PPT strongly upregulated the release of radicals in sodium nitroprusside-treated RAW264.7 cells and the surface levels of costimulatory molecule CD86. More importantly, this compound remarkably suppressed nitric oxide production, morphological changes, phagocytic uptake, cell-cell aggregation, and cell-matrix adhesion in RAW264.7 and U937 cells in the presence or absence of lipopolysaccharide, anti-CD43 antibody, fibronectin, and phorbal 12-myristate 13-acetate. Therefore, our results suggest that 2H-PPT can be applied as a novel functional immunoregulator of macrophages and monocytes.

Keywords: Panax ginseng, 20S-dihydroprotopanaxatriol, Phargocytosis, Morphological changes, Adhesion

INTRODUCTION

Macrophages are important innate immune cells with various immune functions including anticancer, antibacterial, and antiviral [1-3]. These cells are generated by the differentiation of monocytes derived from hematopoietic stem cells. To perform various immunological functions, macrophages require flexible changes in their morphological structures for phagocytic uptake, adhesion to target cells, and surface membrane changes [1-3]. By these cellular responses, cells are eventually able to produce numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and chemoattractants as well as cytotoxic and inflammatory molecules (e.g., nitric oxide [NO], reactive oxygen species [ROS], and prostaglandin E2) [1-3]. Due to their significance in innate immunity, macrophages are considered important cells, useful for anticancer and antiinflammatory purposes [4].

Panax ginseng, a perennial plant of Araiaceae, is an ethnopharmacologically valuable herbal medicine used for enhanced vitality, long life, and supplement of spirits [5]. Although many different species of Genus Panax are cultured, it has been accepted that Korean ginseng (P. ginseng) is one of the best types of ginseng with regard to pharmacological and phytochemical properties [6]. The pharmacological effects of Korean ginseng are mostly managed by ginsenosides and acid polysaccharides [7-9]. Regulatory actions on cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, cancer, stress, and immunostimulation have been reported [7]. Recent studies have investigated ginseng-derived metabolites or derivatives such as compound K, ginsenoside-F1, and 20S-dihydroprotopanaxatriol (2H-PPT) [10-12].

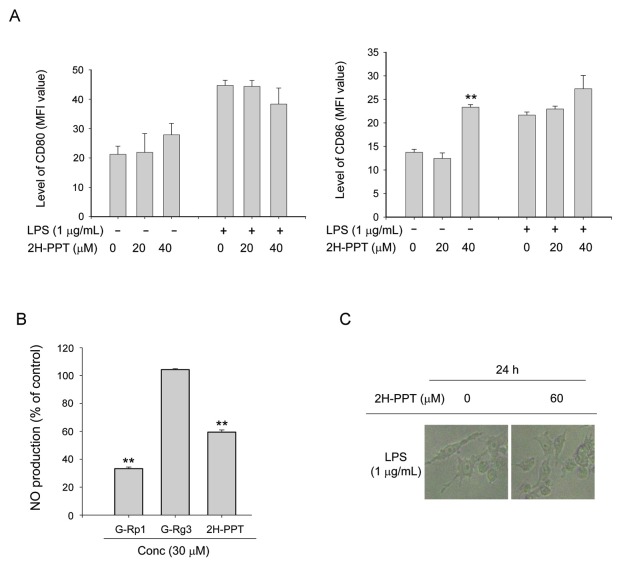

2H-PPT (Fig. 1) is one derivate generated from protopanaxatriol (PPT). Although PPT has been reported to have anti-cancer and anti-oxidative activities, studies have yet to suggest the biological role of 2H-PPT. Therefore, in this study, we explored the regulatory role of 2H-PPT on the cellular responses of the immunologically valuable cells, macrophages and monocytes.

Fig. 1. Chemical structure of 20S-dihydroprotopanaxatriol (2H-PPT) and its effect on cell viability. (A) Chemical structure of 2H-PPT. (B) RAW264.7 or U937 cells (1×106 cells/mL) were incubated with 2H-PPT (0 to 80 μM) for 24 h. Cell viability was determined by conventional MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolum bromide) assay as described in the Materials and Methods section.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

2H-PPT, ginsenoside-Rp1, and ginsenoside-Rg3 were obtained from Ambo Institute (Daejeon, Korea). The purity of these compounds was measured at 95% by HPLC analysis. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), sodium nitroprusside (SNP), crystal violet, and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). U0126, SP600125, and SB203580 were obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). RAW264.7 and U937 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Cell-cell-adhesion-inducing antibodies to CD43 (161-46, ascites, IgG1) were used as reported previously [13,14]. Fibronectin (FN) and R-phycoerythrin-conjugated antibodies to CD80 (16-10-A1), CD82, and CD86 (GL1) were from BD Bioscience (San Diego, CA, USA).

Cell culture

RAW264.7 and U937 cells were cultured in RPMI1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum and with 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin at 37℃ in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability and the extent of proliferation were assessed by conventional 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolum bromide (MTT) assay [15]. RAW264.7 and U937 cells (5×104 cells/well) were incubated with various concentrations of 2H-PPT for 24 h and were further incubated with MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL) for an additional 4 h at 37℃. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 490 nm with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices corp., Menlo Park, CA, USA).

Determination of reactive oxygen species generation

The level of intracellular ROS was determined by a change in fluorescence resulting from the oxidation of the fluorescent probe, H2DCFDA. Briefly, 5×105 cells of RAW264.7 cells were exposed to 2H-PPT for 30 min. After incubation, cells were then incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) as an inducer of ROS production at 37℃ for 6 h. Cells were incubated with 50 μM of the fluorescent probe H2DCFDA for 1 h at 37℃. The degree of fluorescence, corresponding to intracellular ROS, was determined using a FACScan flow cytometer (Beckton-Dikinson, San Jose, CA, USA), as reported previously [16].

Flow cytometric analysis

The expression of co-stimulatory molecules (CD80 [16-10A1, 1:50] and CD86 [GL1, 1:50]) in RAW264.7 cells or differentiation marker (CD82) in PMA-treated or non-treated U937 cells was determined by flow cytometric analysis [15,17]. The RAW264.7 or U937 cells (2×106 cells/mL) treated with 2H-PPT in the presence or absence of LPS (1 μg/mL) or PMA (10 ng/mL) for 12 or 24 h were washed with a staining buffer (containing 2% rabbit serum and 1% sodium azide in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with directly labeled antibodies for an additional 45 min on ice. After washing three times with staining buffer, stained cells were analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson).

Determination of nitric oxide production

After preincubating RAW264.7 cells (1×106 cells/mL) for 18 h, 2H-PPT, ginsenoside-Rp1 or ginsenoside-Rg3 in the presence or absence of LPS (1 μg/mL) was incubated for 24 h, as reported previously [18]. The nitrite in the culture supernatants was measured by adding 100 μL of Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide and 0.1% N-[1-naphthyl]-ethylenediamine dihydrochloride in 5% phosphoric acid) to 100 μL medium samples.

Morphological change test

2H-PPT-treated RAW264.7 or U937 cells in the presence or absence of LPS or PMA were incubated for indicated times. Images of the cells in culture at each time point were obtained using an inverted phase contrast microscope, attached to a video camera, and captured using NIH image software.

Determination of phagocytotic uptake

To measure the phagocytic activity of RAW264.7 cells, we modified a method reported previously [19]. RAW264.7 (5×104) cells treated with 2H-PPT were resuspended in 100 μL PBS containing 1% human AB serum and incubated with fluorescein isothiocynate (FITC)-dextran (1 mg/mL) at 37℃ for 30 min. The incubations were stopped by adding 2 mL ice-cold PBS containing 1% human serum and 0.02% sodium azide. The cells were then washed three times with cold PBS-azide and analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer, as reported previously [16].

Cell-cell or cell-extracellular matrix protein (fibronectin) adhesion assay

U937 cell-cell adhesion assay was performed as reported previously [15,20]. Briefly, U937 cells were pre-incubated with 2H-PPT or MAPK inhibitors (U0126, SB203580, and SP600125) for 1 h at 37℃ and they were further incubated with function-activating (agonistic) anti-CD43 antibody (1 μg/mL) in a 96-well plate. After a 2-h incubation, cell-cell clusters were determined by homotypic cell-cell adhesion assay using a hemocytometer [15,17]. A photo was then taken with an inverted light microscope equipped with a high-performance charge-coupled devices (Diavert) video camera (COUH, San Diego, CA, USA). For a cell-fibronectin adhesion assay, U937 cells (5×105 cells/well) were seeded on a fibronectin (50 μg/mL)-coated plate and incubated for 3 h [21]. After removing unbound cells with PBS, the attached cells were treated with 0.1% of crystal violet for 15 min. The optical density value at 570 nm was measured by a Spectramax 250 microplate reader.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test and a one-way ANOVA were used to determine the statistical significance of the difference between values for the various experimental and control groups. Data are expressed as means±standard errors, and the results were obtained from at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this study, we explored the regulatory function of 2H-PPT (Fig. 1A), an enzymatic metabolite of PPT, on the cellular responses of macrophages and monocytes, including phagocytic uptake, ROS generation, NO production, cell-cell adhesion, morphological change, and regulation of surface adhesion molecules in RAW264.7 murine macrophages and U937 human monocytic cells.

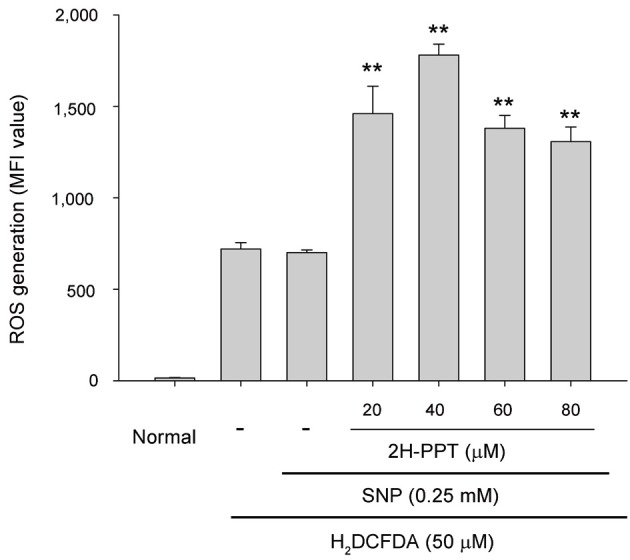

Interestingly, without affecting cell viability (Fig. 1B), 2H-PPT significantly enhanced the release of ROS in SNP-treated RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 2), indicating that this compound could stimulate macrophage cells to release more levels of radicals.

Fig. 2. Effect of 20S-dihydroprotopanaxatriol (2H-PPT) on reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in sodium nitroprusside (SNP)-treated RAW264.7 cells. RAW264.7 cells pre-incubated with 2H-PPT were treated with H2DCFDA (50 μM) in the presence or absence of SNP (0.25 mM) for 2 h. The level of radicals was determined by flow cytometric analysis as described in Materials and Methods section. MFI, mean fluorescence intesity. **p<0.01 compared with normal.

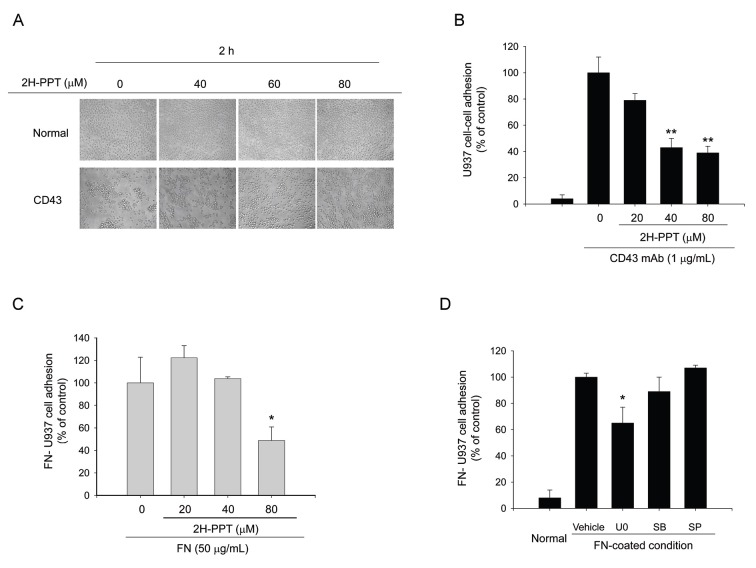

Furthermore, 2H-PPT strongly upregulated the surface level of CD86 (Fig. 3A, right panel), which is known as costimulatory molecules essential for major histocompatibility complex class II/T cell receptor interaction [22], in RAW264.7 cells, implying that macrophages can be activated by the exposure of 2H-PPT. However, under LPS-treated conditions, the upregulatory activity of 2H-PPT was not seen in the expression of CD80 (Fig. 3A, left panel). Rather, this compound suppressed NO production in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3B). Although the inhibitory activity of NO production by 2H-PPT was not higher than that of ginsenoside-Rp1, an anti-inflammatory ginsenoside derivative [23], the NO suppressive activity seems to clearly suggest that 2H-PPT is able to reduce the production of inflammatory mediators such as NO, as in the previously reported cases of other anti-inflammatory ginsenosides like 20S-ginsenoside-Rh2, ginsenoside-Rc, ginsenoside-Rb1, and ginsenoside-Re [23,24]. Interestingly, the suppressive activity of 2H-PPT in RAW264.7 cells was also found in their morphological changes during LPS exposure at 60 μM (Fig. 3C), implying that this compound could modulate morphology-dependent actions of macrophages.

Fig. 3. Effect of 20S-dihydroprotopanaxatriol (2H-PPT) on costimulatory molecule expression, nitric oxide (NO) production, and morphological changes in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated RAW264.7 cells. RAW264.7 cells (2×106 cells/mL) pre-incubated with 2H-PPT were treated with LPS for indicated time. (A) The surface levels of CD80 and CD86 in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells for 12 h were determined by flow cytometry. (B) NO production level was determined by Griess assay using culture supernatants prepared from 2H-PPT-treated cells in the presence or absence of LPS for 24 h. (C) Images of the cells in culture at 24 h were obtained using an inverted phase contrast microscope, attached to a video camera, and captured using NIH image software. MFI, mean fluorescence intesity; G, ginsenoside; Conc, concentration. **p<0.01 compared with control.

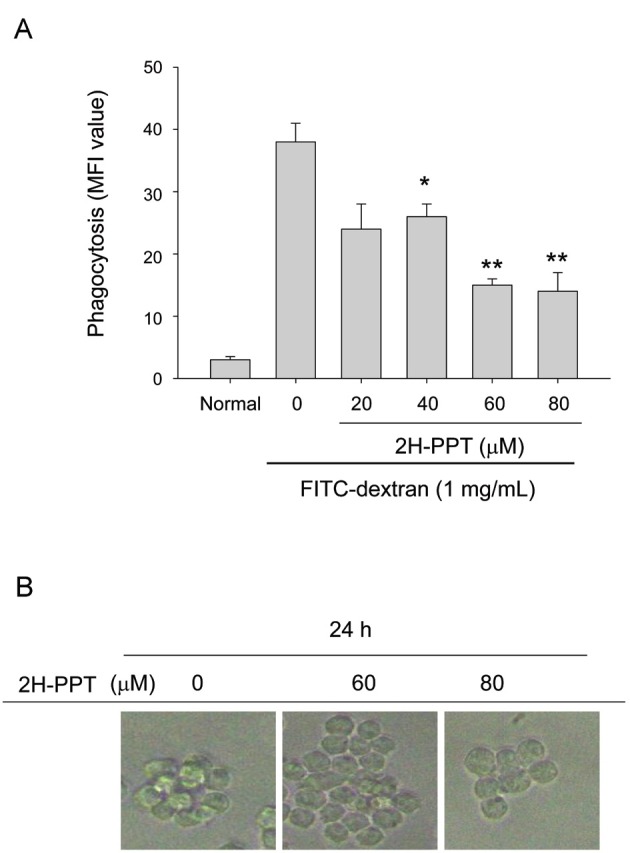

Morphological changes are understood to be critical phenomena in macrophage functions such as phagocytosis, migration, and adhesion to other cells [25,26]. Furthermore, we have also reported that interruption of morphological changes induced by LPS leads to the diminishment of inflammatory responses of macrophages [27,28]. Therefore, we next examined whether 2H-PPT is capable of controlling phagocytic responses of RAW264.7 cells. To do this, we employed FITC-labeled dextran and measured its florescence level in RAW264.7 cells by flow cytometric analysis.

As Fig. 4A indicates, 2H-PPT strongly blocked the phagocytic uptake of the dextran at 60 to 80 μM, suggesting that this compound could modulate morphological change-based cellular responses in RAW264.7 cells. Supportively, the strength of the RAW264.7 cell cluster was also reduced by 2H-PPT (Fig. 4B). Therefore, these results strongly indicate that 2H-PPT could have the ability to modulate functional activation of fully differentiated macrophages in a morphological change-based manner.

Fig. 4. Effect of 20S-dihydroprotopanaxatriol (2H-PPT) on phagocytic uptake and clustering formation in RAW264.7 cells. (A) RAW264.7 cells pre-incubated with 2H-PPT were treated with fluorescein isothiocynate-dextran (1 mg/mL) for 2 h. The level of dextran uptake was determined by flow cytometric analysis as described in Materials and Methods section. (B) Effect of 2H-PPT on clustering formation of RAW264.7 cells was analyzed by taking a picture of incubated cells. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; FITC, Fluorescein isothiocyanate. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 compared with control.

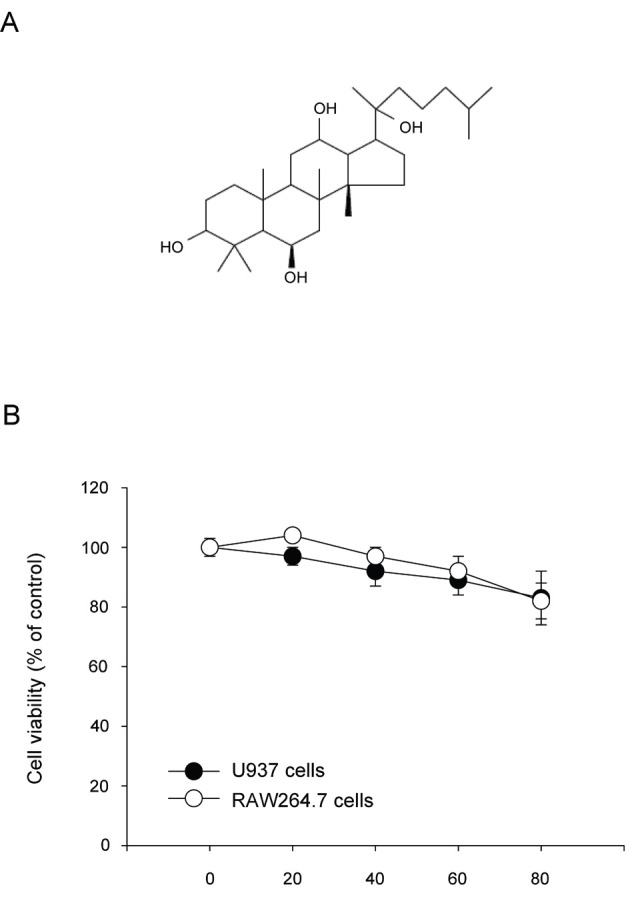

The morphology-based cellular response was also observed in monocytic cells. Thus, we have reported that promonocytic U937 cells can be a useful model to study morphological change-based cell adhesion [15,17]. For example, anti-CD43 mAb treatment was found to trigger homotypic cell-cell adhesion of U937 cells mediated by CD43 [29], which is one of the representative adhesion molecules [30]. Immobilized fibronectin was able to induce β1-integrin-mediated cell adhesion [14]. Therefore, using previously established conditions, we examined whether 2H-PPT could modulate U937 cell adhesion events. In agreement with results obtained with macrophages, it was revealed that this compound is capable of significantly reducing both CD43-mediated homotypic aggregation (Fig. 5A, B) and fibronectin/β1-integrin-mediated cell adhesion events (Fig. 5C), as seen in the significantly inhibited case of ERK inhibitor U0126 (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5. Effects of 20S-dihydroprotopanaxatriol (2H-PPT) on U937 cell adhesion. (A,B) U937 cells (1×106 cells/mL) pretreated with 2H-PPT were incubated in the presence or absence of pro-aggregative antibodies (1 μg/mL each) to CD43 (161-46) for 30 min. Images of the cells in culture were obtained using an inverted phase contrast microscope attached to a video camera. Quantitative evaluation of U937 cell-cell clusters was performed by a quantitative cell-cell aggregation assay. (C,D) Effects of 2H-PPT or MAPK inhibitors, U0 [U0126], SB [SB203580], and SP [SP600125], on cell-fibronectin (FN) adhesion were examined with U937 cells pretreated with 2H-PPT by seeding on FN (50 μg/mL)-coated plates for 3 h. Attached cells were determined by crystal violet assay, as described in Materials and Methods section. Data represent mean±standard error of three independent observations performed in triplicate. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 compared to control.

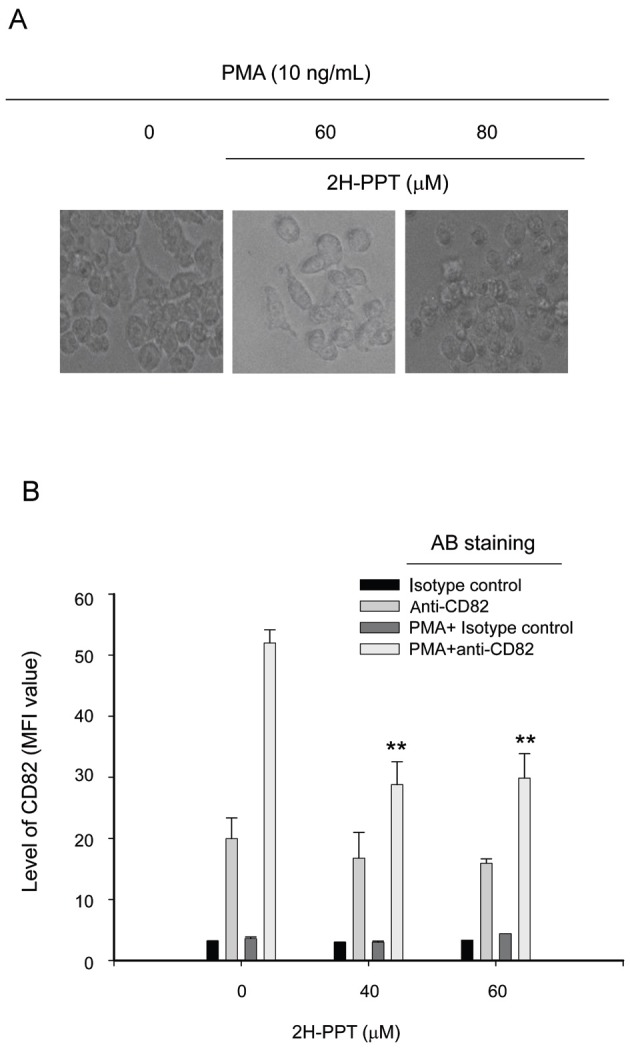

Finally, we investigated whether PMA-treated morphological change and differentiation of monocytic cells could be controlled by 2H-PPT. As Fig. 6A depicts, this compound blocked the morphological change of U937 cells under PMA treatment conditions. In addition, PMA-induced differentiation was also reduced by 2H-PPT (Fig. 6B), according to the measured level of CD82, a differentiation marker of monocytes into macrophages [31], implying that 2H-PPT suppresses the differentiation process of monocytes into macrophages.

Fig. 6. Effect of 20S-dihydroprotopanaxatriol (2H-PPT) on CD82 expression and morphological changes in phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-treated U937 cells. U937 cells (2×106 cells/mL) pre-incubated with 2H-PPT were treated with PMA for 24 h. (A) Images of the cells in culture at 24 h were obtained using an inverted phase contrast microscope, attached to a video camera, and captured using NIH image software. (B) The surface levels of CD82 in PMA-treated RAW264.7 cells were determined by flow cytometry. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. **p<0.01 compared with normal.

However, whether differentiation is first blocked by 2H-PPT or whether suppression of morphological changes is directly linked to differentiation of monocytes is not clear in this study. Further experiments will be performed to elucidate these molecular mechanisms.

Morphological changes and cell adhesion are normal important cellular events for immune responses, angiogenesis, and embryogenesis [32,33]. More importantly, when cancer cells are in metastatic phases, these responses are also critical. In fact, suppression of adhesion responses of breast cancer cells has been known to block their metastatic characteristics [34]. Consequently, suppression of cellular migration and adhesion is now agreed to be one therapeutic tool in treating cancer metastasis. It is assumed that 2H-PPT can be also applied as anti-cancer drugs targeted to cancer cell adhesion and metastasis with efficacy to modulate morphological alteration and cell-cell or cell-tissue adhesions. Since morphological changes and cell-cell adhesion have been found to be modulated by actin cytoskeleton change [15,29,35], how 2H-PPT is capable of controlling these events in terms of actin cytoskeleton rearrangement will be further studied.

In conclusion, we have found that 2H-PPT was able to suppress various cellular events such as phagocytic uptake, NO production, morphological changes, monocytic differentiation, and cell-cell/cell-fibronectin adhesion events. These results strongly suggest that 2H-PPT can act as a functional immunomodulator of macrophages and monocytes. In addition, considering that these cellular events are critical steps in cancer cell migration and metastasis, it is assumed that 2H-PPT can be applied as a novel modulator targeted to cell morphology-dependent phenomena. Further in vivo efficacy and molecular mechanism studies on cancer migration and metastasis will be continued in the next project.

References

- 1.Lee YG, Lee J, Byeon SE, Yoo DS, Kim MH, Lee SY, Cho JY. Functional role of Akt in macrophage-mediated innate immunity. Front Biosci. 2011;16:517–530. doi: 10.2741/3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu T, Yi YS, Yang Y, Oh J, Jeong D, Cho JY. The pivotal role of TBK1 in inflammatory responses mediated by macrophages. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:979105. doi: 10.1155/2012/979105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byeon SE, Yi YS, Oh J, Yoo BC, Hong S, Cho JY. The role of Src kinase in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:512926. doi: 10.1155/2012/512926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeannin P, Duluc D, Delneste Y. IL-6 and leukemia-inhibitory factor are involved in the generation of tumor-associated macrophage: regulation by IFN-gamma. Immunotherapy. 2011;3(4 Suppl):23–26. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasani-Ranjbar S, Nayebi N, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of herbal medicines used in the treatment of obesity. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3073–3085. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim DH. Chemical diversity of Panax ginseng, Panax quinquifolium, and Panax notoginseng. J Ginseng Res. 2012;36:1–15. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2012.36.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasegawa H. Proof of the mysterious efficacy of ginseng: basic and clinical trials: metabolic activation of ginsenoside: deglycosylation by intestinal bacteria and esterification with fatty acid. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;95:153–157. doi: 10.1254/jphs.FMJ04001X4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byeon SE, Lee J, Kim JH, Yang WS, Kwak YS, Kim SY, Choung ES, Rhee MH, Cho JY. Molecular mechanism of macrophage activation by red ginseng acidic polysaccharide from Korean red ginseng. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:732860. doi: 10.1155/2012/732860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwak YS, Kyung JS, Kim JS, Cho JY, Rhee MH. Anti-hyperlipidemic effects of red ginseng acidic polysaccharide from Korean red ginseng. Biol Pharm Bull. 2010;33:468–472. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee BH, Choi SH, Shin TJ, Hwang SH, Kang JY, Kim HJ, Kim BJ, Nah SY. Effects of ginsenoside metabolites on GABAA receptor-mediated ion currents. J Ginseng Res. 2012;36:55–60. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2012.36.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choo MK, Sakurai H, Kim DH, Saiki I. A ginseng saponin metabolite suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha-promoted metastasis by suppressing nuclear factor-kappaB signaling in murine colon cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2008;19:595–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim YS, Yoo MH, Lee GW, Choi JG, Kim KR, Oh DK. Ginsenoside F1 production from ginsenoside Rg1 by a purified β-glucosidase from Fusarium moniliforme var. subglutinans. Biotechnol Lett. 2011;33:2457–2461. doi: 10.1007/s10529-011-0719-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho JY, Kim AR, Joo HG, Kim BH, Rhee MH, Yoo ES, Katz DR, Chain BM, Jung JH. Cynaropicrin, a sesquiterpene lactone, as a new strong regulator of CD29 and CD98 functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313:954–961. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim BH, Lee YG, Lee J, Lee JY, Cho JY. Regulatory effect of cinnamaldehyde on monocyte/macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:529359. doi: 10.1155/2010/529359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho JY, Fox DA, Horejsi V, Sagawa K, Skubitz KM, Katz DR, Chain B. The functional interactions between CD98, beta1-integrins, and CD147 in the induction of U937 homotypic aggregation. Blood. 2001;98:374–382. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.2.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YG, Lee WM, Kim JY, Lee JY, Lee IK, Yun BS, Rhee MH, Cho JY. Src kinase-targeted anti-inflammatory activity of davallialactone from Inonotus xeranticus in lipopolysaccharide-activated RAW264.7 cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:852–863. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee YG, Lee J, Cho JY. Cell-permeable ceramides act as novel regulators of U937 cell-cell adhesion mediated by CD29, CD98, and CD147. Immunobiology. 2010;215:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang TJ, Moon JS, Lee S, Yim D. Polyacetylene compound from Cirsium japonicum var. ussuriense inhibits the LPS-induced inflammatory reaction via suppression of NF-kappaB activity in RAW 264.7 cells. Biomol Ther. 2011;19:97–101. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2011.19.1.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang SA, Kang SC, Sohn EH. Phagocytic effects of beta-glucans from the mushroom Coriolus versicolor are related to dectin-1, NOS, TNF-alpha signaling in macrophages. Biomol Ther. 2011;19:438–444. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2011.19.4.438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho JY, Skubitz KM, Katz DR, Chain BM. CD98-dependent homotypic aggregation is associated with translocation of protein kinase Cdelta and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases. Exp Cell Res. 2003;286:1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4827(03)00106-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larrucea S, Gonzalez-Rubio C, Cambronero R, Ballou B, Bonay P, Lopez-Granados E, Bouvet P, Fontan G, Fresno M, Lopez-Trascasa M. Cellular adhesion mediated by factor J, a complement inhibitor. Evidence for nucleolin involvement. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31718–31725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YG, Byeon SE, Kim JY, Lee JY, Rhee MH, Hong S, Wu JC, Lee HS, Kim MJ, Cho DH, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of Hibiscus cannabinus extract on macrophage functions. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim BH, Lee YG, Park TY, Kim HB, Rhee MH, Cho JY. Ginsenoside Rp1, a ginsenoside derivative, blocks lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-1beta production via suppression of the NF-kappaB pathway. Planta Med. 2009;75:321–326. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1112218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bi WY, Fu BD, Shen HQ, Wei Q, Zhang C, Song Z, Qin QQ, Li HP, Lv S, Wu SC, et al. Sulfated derivative of 20(S)-ginsenoside Rh2 inhibits inflammatory cytokines through MAPKs and NF-kappa B pathways in LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages. Inflammation. 2012;35:1659–1668. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9482-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mork T, Hancock RE. Mechanisms of nonopsonic phagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3287–3293. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3287-3293.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaguchi H, Haranaga S, Widen R, Friedman H, Yamamoto Y. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection induces differentiation of monocytes into macrophages. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2392–2398. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2392-2398.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim JY, Lee YG, Kim MY, Byeon SE, Rhee MH, Park J, Katz DR, Chain BM, Cho JY. Src-mediated regulation of inflammatory responses by actin polymerization. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:431–443. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kustermans G, El Mjiyad N, Horion J, Jacobs N, Piette J, Legrand-Poels S. Actin cytoskeleton differentially modulates NF-kappaB-mediated IL-8 expression in myelomonocytic cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76:1214–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho JY, Chain BM, Vives J, Horejsi V, Katz DR. Regulation of CD43-induced U937 homotypic aggregation. Exp Cell Res. 2003;290:155–167. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4827(03)00322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenstein Y, Santana A, Pedraza-Alva G. CD43, a molecule with multiple functions. Immunol Res. 1999;20:89–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02786465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lebel-Binay S, Lagaudriere C, Fradelizi D, Conjeaud H. CD82, tetra-span-transmembrane protein, is a regulated transducing molecule on U937 monocytic cell line. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:956–963. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.6.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melo RC. Acute heart inflammation: ultrastructural and functional aspects of macrophages elicited by Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:279–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galli SJ, Tsai M. Mast cells: versatile regulators of inflammation, tissue remodeling, host defense and homeostasis. J Dermatol Sci. 2008;49:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou T, Marx KA, Dewilde AH, McIntosh D, Braunhut SJ. Dynamic cell adhesion and viscoelastic signatures distinguish normal from malignant human mammary cells using quartz crystal microbalance. Anal Biochem. 2012;421:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho JY, Katz DR, Chain BM. Staurosporine induces rapid homotypic intercellular adhesion of U937 cells via multiple kinase activation. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:269–276. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]