Summary

In recent decades the increase in antibiotic‐resistant bacterial strains has become a serious threat to the treatment of infectious diseases. Drug resistance of Staphylococcus aureus has become a major problem in hospitals of many countries, including developed ones. Today the interest in alternative remedies to antibiotics, including bacteriophage treatment, is gaining new ground. Here, we describe the staphylococcal bacteriophage Sb‐1 – a key component of therapeutic phage preparation that was successfully used against staphylococcal infections during many years in the Former Soviet Union. This phage still reveals a high spectrum of lytic activity in vitro against freshly isolated, genetically different clinical samples (including methicillin‐resistant S. aureus) obtained from the local hospitals, as well as the clinics from different geographical areas. The sequence analyses of phage genome showed absence of bacterial virulence genes. A case report describes a promising clinical response after phage application in patient with cystic fibrosis and indicates the efficacy of usage of Sb‐1 phage against various staphylococcal infections.

Introduction

During the last decades, a dramatic worldwide increase of antibiotic‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections was observed (Ayliffe, 1997; Chambers, 1997; Herold et al., 1998; Cosgrove et al., 2003). The CDC estimates that 80 000 hospitalized patients experienced a nosocomial infection with methicillin‐resistant S. aureus (MRSA) every year. Alternative treatment options to antibiotics are therefore urgently needed. One potential treatment option for antibiotic‐resistant S. aureus is lytic bacteriophages, which naturally infect S. aureus (Merril et al., 1996; Barrow and Soothill, 1997; Carlton, 1999; Chanishvili et al., 2001; Duckworth & Gulig, 2002; Inal, 2003; Bruttin and Brussow, 2005; Merril et al., 2006) known as phage therapy. Phages, unlike antibiotics, are specifically targeted to a particular bacterial species and thus spare bystander bacteria from other species lytic damage. Phages thus much less affect the balance of normal microflora than antibiotics. The G. Eliava Institute of Bacteriophages, Microbiology and Virology (Tbilisi, Georgia) was the first centre, where therapeutic phage cocktails targeting various bacterial pathogens were developed. Several cocktails were for many decades successfully used against S. aureus in Georgian hospitals (Chanishvili and Sharp, 2008; Kutateladze and Adamia, 2008).

In 1977, L. Kvachadze isolated a particularly active phage from an Eliava Institute phage cocktail used to treat staphylococcal infections. The phage isolate was named Sb‐1 and its properties were described in Russian/Georgian publications (Andriashvili et al., 1981; Ackermann and Abedon, 2001). Sb‐1 is particularly well suited for phage therapy. It is a strictly ‘virulent’ phage, i.e. it propagates exclusively by lytic infections and does not establish a lysogenic state. ‘Virulent’ phages in contrast to temperate phages do not carry bacterial pathogenicity genes. Sb‐1 has a very broad host range on S. aureus, including antibiotic‐resistant strains. Its genome was sequenced and no known virulence genes were identified. The sequence confirms also our previous observation that the Sb‐1 genome includes no GATC sequences (Andriashvili et al., 1986). which are the target of Sau3A, the major restriction enzyme found in many S. aureus strains. This article presents a further characterization of Sb‐1, its genome map, biological properties, host range against a broad panel of clinical isolates including MRSA strains, and sample clinical data including a case report of its successful application against a chronic S. aureus infection in a cystic fibrosis patient.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the Sb‐1 phage

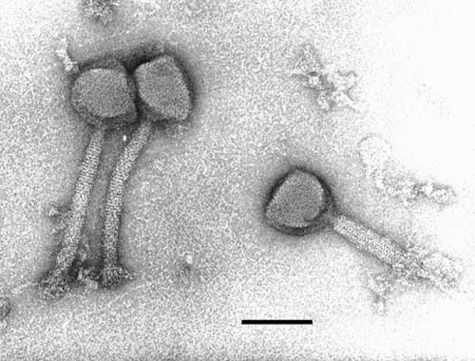

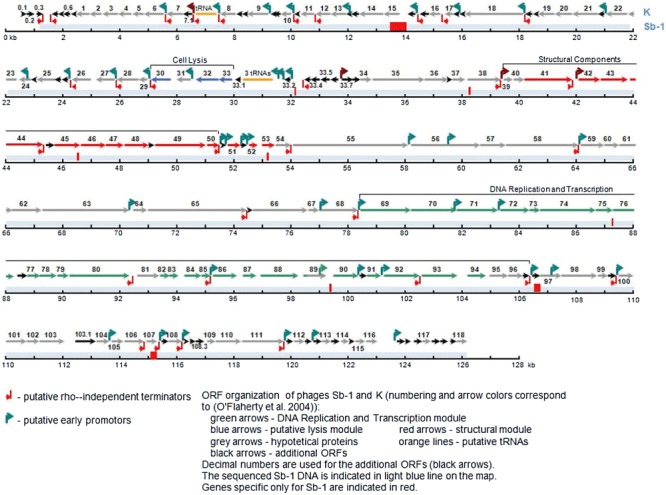

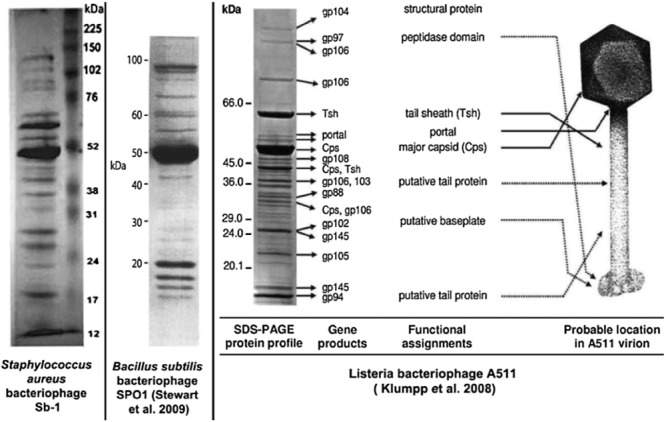

The electron microscopy of the purified Sb‐1 phage (Fig. 1) displays a typical SPO1‐like phage, a class of Myoviridae (phages with contractile tail) that is widely distributed in low GC content Gram‐positive bacteria. Its genomic map (Fig. 2, sequence GenBank Accession No. HQ163896) confirmed this analysis and identified Sb‐1 as a close relative of S. aureus phage K (Rees and Fry, 1981; O'Flaherty et al., 2004). A number of SPO1‐like S. aureus phage genomes have been sequenced and none showed bacterial virulence genes or any other undesired genes (Stewart, 1993; Yarwood et al., 2002; Chibani‐Chenooufi et al. 2004; Klumpp et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2009). This was also the case for the phage Sb‐1 genome. A number of specific host‐lethal genes have been identified which may contribute to its efficacy; a characterization of the properties and effects of some of these genes will be published separately, along with a more detailed genomic analysis. Comparative protein analysis of SPO1‐like phages with different host bacteria confirmed the relatedness of phages on level of structural proteins (Fig. 3) (Klumpp et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Electron micrograph of Sb‐1 phage (bar = 100 nm).

Figure 2.

Genome sequence of Sb‐1 bacteriophage.

Figure 3.

Comparison of structural proteins of morphologically related bacteriophages.

Antibiotic and phage susceptibility of S. aureus isolates

Between 2004 and 2009 we obtained 352 isolates of epidemiologically unrelated S. aureus from diagnostic centres and hospitals of Tbilisi. The strains were isolated from patients showing infected wounds, furuncles, otitis externa, eye, nose, gum, throat and urinary tract infections. Each isolate was tested for resistance to various antibiotics and against phage Sb‐1. Less than 2% of the isolates were resistant to phage Sb‐1, while antibiotic resistance levels ranged from 7.2% to 99.7%, respectively, for the different antibiotics.

Pulsed field gel electrophoresis analysis

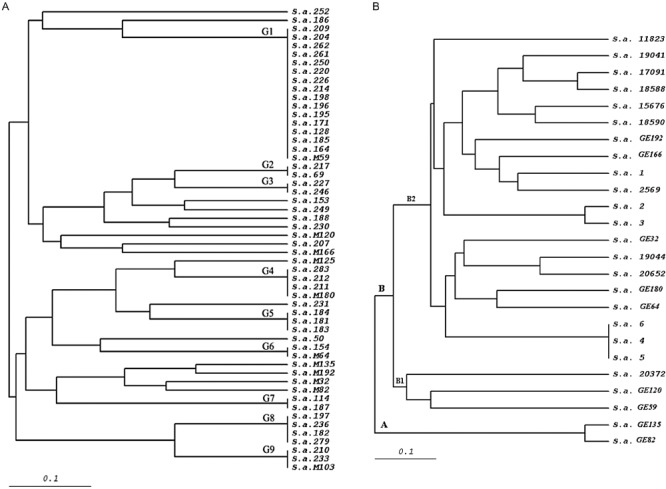

A coverage of greater than 98% is exceptional for a single phage isolate. Therefore we controlled whether the high coverage of Sb‐1 phage was the consequence of a collection containing closely related S. aureus strains. We explored the diversity of our S. aureus strain collection by investigating 54 of the 352 isolated by pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Visual analysis of the PFGE results identified 25 distinct restriction pattern. The isolates could be classified into nine multi‐strain branches by unweighted‐pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA) dendrogram analysis (Fig. 4A). One branch of group 1 was represented by 16 isolates. The other branches were represented by at most four different isolates. Antibiotic resistance pattern of 54, genotyped bacterial strains showed that bacteria reveal high resistance to polypeptides, β‐lactames, bacitracin and aminoglycosides (Table 1).

Figure 4.

UPGMA dendrogram of S. aureus strains: (A) strains isolated from the patients from local hospitals, (B) MRSA strains from Georgia (GE) and Germany.

Table 1.

Percentage of antibiotic resistance of genetically different clinical Staphylococcus aureus strains.

| PFGE groups | Bacterial strain | β‐Lactames | Aminoglycosides | Tetracycline | Macrolides | Chloramphenicol | Polypeptides | Ciprofloxacin | Methicillin | Bacitracin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 16 | 100 | 68.7 | 37.5 | 68.7 | 25 | 100 | 50 | 6.25 | 100 |

| G2 | 2 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 0 | 100 |

| G3 | 2 | 100 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| G4 | 4 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 75 | 50 | 100 | 75 | 25 | 100 |

| G5 | 3 | 100 | 100 | 33.3 | 66.6 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| G6 | 2 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 100 |

| G7 | 2 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| G8 | 4 | 50 | 100 | 75 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 75 | 0 | 100 |

| G9 | 3 | 33.3 | 100 | 66.6 | 0 | 33.3 | 100 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 66.6 |

| Individual | 16 | 93.75 | 75 | 37.5 | 43.75 | 31.25 | 100 | 62.5 | 43.75 | 87.5 |

| Total | 54 | 88.8 | 81.4 | 44.4 | 55.5 | 29.6 | 100 | 61.1 | 20.3 | 94.4 |

Test against S. aureus isolates from a different geographical area

In order to exclude a geographic bias, the lytic activity of phage Sb‐1 was also tested against the S. aureus strain collection from the DSMZ (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH Germany; German collection of microorganisms and cell cultures). The tested strains included 50 MRSA and 43 toxin‐producing MSSA strains. We observed again a variable PFGE pattern with these strains and the German MRSA isolates differed from the Georgian MRSA isolates (Fig. 4B). None of the strains was resistant to the phage used at high titre (1 × 1011 pfu ml−1). Ten strains showed resistance to the phage at a lower titre of 1 × 109 pfu ml−1. However, after propagation of Sb‐1 on these less sensitive bacteria, all 10 strains were subsequently lysed by the low titre of phage.

Efficiency of plating

One might object that the lytic activity against such a wide range of strains could reflect an enzymatic lysis effect (lysis from without or soluble phage lysin effects) and not true replication of Sb‐1 on the test strains. This was not the case as demonstrated by an efficiency of plating (eop) test. On 25 out of 27 distinct strains, the plaque count of Sb‐1 on the test strain was high when compared with the plaque count on the propagating strain (eop of 0.1–1) (Table 2). Test strains for the eop experiments were selected from each PFGE subgroups. The plaque assay demonstrates that the wide host range of Sb‐1 on S. aureus strains is not an artefact of the spot test.

Table 2.

Efficiency of plating of phage Sb‐1 on different strains of S. aureus.

| Strain of S. aureus | 32 | 69 | 103 | 153 | 154 | 164 | 182 | 183 | 184 | 186 | 187 | 188 | 197 | 207 | 212 | 214 | 217 | 220 | 227 | 229 | 230 | 231 | 233 | 236 | 246 | 250 | 279 |

| Efficiency of plating | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0.2 | 1 |

Phage‐resistant S. aureus strains

Five S. aureus strains from Georgian patients were only weakly susceptible towards phage Sb‐1. In the spot test only an incomplete ‘opaque lysis’ phenotype was observed. These strains came from five different patients and three different anatomical sites (N390 was isolated from the vagina; N392 and N396 from urine; N394 and 395 from the eye). In PFGE analysis strains N390, 396 and 395 could not be distinguished while N394 was clearly distinct (data not shown).

On these phage‐resistant cells, blind serial passages of phage Sb‐1 were performed in liquid and solid media. In the first passages, no phage plaques were detected. However, after several passages, the titre of the phage rose to 107–108 pfu ml−1.

The adsorption of Sb‐1 phage was relatively low on the S. aureus strains showing the opaque lysis spot phenotype (50–65% input phage adsorbed after 5 min of incubation). When Sb‐1 derivative phages finally achieved high titres on the initially phage‐resistant cells, 89–95% of the input phages were adsorbed after 5 min (data not shown).

Phage escape mutants

Next we tested to what extent phage‐resistant cells appeared in a culture of phage‐sensitive S. aureus strains infected with phage Sb‐1 in liquid culture. Two propagating strains (N50, N164) and a clinical MRSA isolate (N125) were used for this experiment. We observed only a low level of phage escape mutants: frequency of mutation on S. aureus 50 strain was 2.2 × 10−7, on strains S. aureus 125 and 164, 1.2 × 10−7 and 1.1 × 10−9 respectively. Only few of the colonies growing in the presence of Sb‐1 could be serially passages: most of them had converted back to the phage‐sensitive phenotype.

Sample clinical applications

For many years, the Eliava Institute in Tbilisi was producing a staphylococcal phage preparation which was effectively used locally (topically). In late 1970s, the Institute scientists elaborated a method for construction of the phage for intravenous use. In the series of experiments, therapeutic effectiveness was studied to treat different infectious diseases, including acute and chronic sepsis, peritonitis, osteomyelitis, mastitis, purulent arthritis, acute and chronic lung abscesses, chronic pneumonia and bronchitis, bronchoectasis, purulent cysts and others. Sb‐1 phage was the key component of the therapeutic preparation.

In some cases when the approved cocktails (commercial preparations) do not work in vitro against the pathogen isolated from patient's samples, we isolate specific ‘autophage’ against patient's specific bacteria and use these phages for treatment of the patient. We present an example of current clinical application of Sb‐1 phage with commercially available Pyophage in patient with cystic fibrosis.

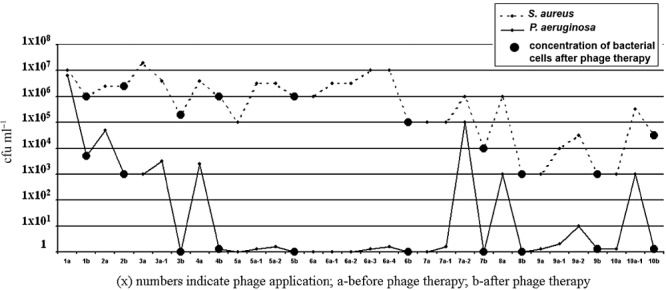

Case report. Patient M. Kh. was a 7‐year‐old girl suffering from cystic fibrosis diagnosed in 2002. The disease was confirmed by genetic analyses: she is homozygous for the mutation –1677 deLTA. The sweat test revealed a strongly elevated chloride concentration of 126–135 mmol l−1. She showed a chronic colonization of the lungs with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and S. aureus. During several years, the patient was treated with broad spectrum antibiotics, but there was no effect on the P. aeruginosa and S. aureus colonization. The initial bacterial concentration (before phage application) in the patient's sputum was 1 × 107 cfu ml−1 for S. aureus, and 8 × 106 cfu ml−1 for P. aeruginosa. Phage treatment was provided nine times by nebulizer (with approximately 4‐ to 6‐week interval between phage therapies) and bacteriological analysis was performed at 1‐month time intervals.

After the first Pyophage application, the concentration of P. aeruginosa drastically decreased – 7 × 103 cfu ml−1, but the S. aureus titre was not so strongly affected, dropping only to 1 × 106 cfu ml−1. This reflected a weak susceptibility of the strain to Pyophage in vitro. During a month when no phage therapy was administered, the amount of P. aeruginosa remained minimal – 7 × 104 cfu ml−1.

The physician decided to add use of now well‐characterized phage Sb‐1, which had high lytic activity against the patient's specific culture in vitro. Sb‐1 phage was added to the Pyophage cocktail and applied this augmented phage cocktail five times with a nebulizer to the patient. After the joint application (Pyophage with Sb‐1 staphylococcal phage), the amount of S. aureus drastically decreased and during a medication‐free month, the level of S. aureus remained fairly low, at about 103–105 cfu ml−1; for P. aeruginosa, it was 10–100 cfu ml−1. No adverse effects were seen in the patient upon application of the Sb‐1 phage.

We examined the concentration of phages (staphylococcal and P. aeruginosa) in the patient's sputum during phage treatment. Three to four hours after phage application, phage was detected at 102 pfu ml−1. On the second day, before the next phage application, no phage was detected in the sputum (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Concentration of bacterial cells in sputum of the patient before and after phage application.

Subsequent to phage therapy, the general condition of patient improved. Most notably, the follow‐up of the S. aureus level in the sputum showed a steady decrease over 2 months until S. aureus slipped under the detection level after a month. In contrast P. aeruginosa levels showed comparative constancy during 12 months, but at the end of the observation period P. aeruginosa titres reached to × 105 pfu ml−1, but after therapy, no bacteria was found in the sputum.

The most important fact is that the use of antibiotics in the complex therapy was able to be decreased by 50%. However, no significant improvement has yet been seen in the X‐ray and blood analyses. The patient is still under treatment.

Conclusion

Phage cocktails against pyogenic infections (Pyophage) have a long history of reportedly safe in the former Soviet Union. This phage cocktail is still today sold in Georgia and Russia as a registered over‐the‐counter medicine. However, since neither the phage preparation nor the clinical trials conducted with them were published in Western scientific journals, claims on their efficacy were seen with substantial scepticism by Western scientists. Here we demonstrate that S. aureus phage Sb‐1 is a representative of the SPO1 group of Myoviridae, which can be considered as safe with respect to its genome sequence. The phage can be purified and showed a broad host range against large and representative S. aureus strain collections from different geographical areas, including MRSA strains. Phage resistance development is very low and largely reverts to sensitivity. A case study in a cystic fibrosis patient showed no adverse events of phage application in a nebulizer and a promising clinical response. Placebo‐controlled double‐blinded clinical trials are now warranted to test the value of Sb‐1 phage against S. aureus infections in defined clinical situations.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains

A total of 352 hospital strains of S. aureus, including our standard host strain, S. aureus 50, were obtained from patients in various clinics of Tbilisi between 2004 and 2009.

Resistance testing

Resistance to antibiotics was determined by the disc diffusion method on Brain–Heart Infusion agar (Difco). Discs of antibiotics with specified concentrations were obtained from ‘BBL’ (BD BBL Sensi‐Disc) and used following the manufacturer's protocol. Resistance to Sb‐1 was determined by the spot test and determination of efficiency of platting. A culture was considered resistant if the phage or antibiotic caused no visible decrease in bacterial growth.

Bacterial growth conditions

Staphylococcus aureus 50 was routinely grown at 37°C in Brain–Heart Infusion or in semi‐synthetic liquid medium (Kellenberger, 1962) supplemented with 0.1% casein hydrolysate and 0.1% yeast autolysate, to an OD590 of 0.9–1.0 (5 × 108 cells ml−1).

Phage propagation and purification

Phage was added to exponentially growing bacterial cultures at an moi of 0.1. For large‐scale phage cultivation, a modified Frazer fermentor (13 l) (Tikhonenko, 1973) was used and the culture was incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Primary purification and concentration of the phage lysate was performed by chromatography using an ion‐exchange DEAE cellulose column and then differential centrifugation (5000 g, 18 000 g) (Tikhonenko et al., 1963; Tikhonenko, 1973). Purified phages were suspended in SSC buffer (0.15 mM NaCl, 0.015 mM Na citrate, pH 7.0). Final purification of native virions was carried out by centrifugation at 18 000 g through a CsCl gradient in an SW25 rotor using a Beckman L2‐65B ultracentrifuge at 4°C. Phage fractions were dialysed against SSC. Single‐step growth studies were performed as described by Adams (1961, p. 416).

Electron microscopy studies

Morphology of phage particles was studied by electron microscope JEM 1200EX (JEOL). Parlodion (Mallinckrodt) plates were overlaid by phage suspensions (1010 pfu ml−1) and contrasted by uranylacetate.

Study of phage structural proteins

Phage suspensions (60 mkl, 1010–1011 pfu ml−1) were added in 13.3 mkl of sample buffer [8% of SDS, 2 ml of glycerol, 2 ml of 0.5% bromophenol blue, made up to 10 ml with 0.1 M Tris‐HCl (pH 6.5), and 8 mkl of β‐mercaptoethanol was added to 100 mkl of this solution prior to use].

Samples then were boiled for 10 min before being loaded onto 10% polyacrylamide gel (Laemmli, 1970).

Electrophoresis was carried out at 60 v, 9 mA during 18 h in running – Tris‐glycine buffer (3.02 g of Tris base, 14.4 g of glycine, 1 g of SDS, made up to 1 l with deionized water).

Analysis of staphylococcal DNA by PFGE

Overnight cultures were diluted to an OD540 of 0.8–0.9 and bacteria from 500 µl of medium were collected by centrifugation at 5 000 r.p.m. for 15 min, washed with buffer (10 mM Tris base, 1 M NaCl), re‐centrifuged in the same conditions, and the bacterial cell pellet resuspended in the same buffer (250 µl). Two hundred and fifty microlitres was mixed with an equal volume of (50°C) 1% SeaKem agarose (BioProducts, USA) and then pipetted into a plug mould. The solid agarose plugs were incubated at 37°C for 24 h in 2 ml of lysis buffer I [6 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.6, 1 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 0.5% Brij 58, 0.2% Deoxycholate, 0.5% sodium lauryl sarcosine, lysozyme (1 mg ml−1), RNase (20 mkg ml−1), lysostaphin (60 mkg ml−1)]. The plugs were then incubated at 55°C for 24 h in lysis buffer II [0.5 M EDTA, pH 9.0, 1% sodium lauryl sarcosine, proteinase K (50 mkg ml−1)]. The plugs were washed three times with TE buffer (Mulvey et al., 2001; Montensinos et al., 2002). The DNA was digested using 25 U of SmaI (BioLab, USA) for 16 h at 25°C. DNA fragments were resolved on a 1.2% agarose gel (SeaKem gold, USB, USA) using a Gene Navigator System apparatus (Amersham Biosciences) for 18 h at 200 V at 14°C with switching times ramped from 5 to 60 s. After electrophoresis, gels were stained with ethidium bromide, rinsed and photographed under UV light. We used SmaI because it had previously been shown to digest the S. aureus genome into 15–20 restriction fragments, ranging from 5 to 400 kb, giving different patterns with different strains (Tenover et al., 1995). Macrorestriction patterns were analysed visually. Isolates with identical restriction patterns in size and number of bands were considered the same type; isolates that differed from main types by one to two band shifts were assigned subtypes. Clustering of strains was based on the UPGMA. A dendrogram was generated with standard Freetree and Treeview‐based Genetic Distance similarity software.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr John Drake (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, North Caroline, USA) for financial support provided for the phage genome sequencing. We thank Nikoloz Nikolaishvili for the annotation of Sb‐1 phage genome sequence (the Eliava Institute, Tbilisi, Georgia).

We are grateful to Dr Sebastian Suerbaum from the Medical High school (MHH, Hannover, Germany) for the gift of MRSA bacterial strains and Dr Harald Bruessow (Nestle Research Centre, Lausanne, Switzerland) for providing very helpful comments and suggestions.

The research is partly supported by the International Science and Technology Center (ISTC G510).

References

- Ackermann H.‐W., Abedon S. 2001. , and ) Bacteriophage names 2000 [WWW document]. URL http://www.mansfiled.ohio‐state.edu.

- Adams M. 1961. Bacteriophages. Moscow: Publishers of Foreign Literature.

- Andriashvili I., Kvachadze L., Adamia R., Tushishvili D., Kalandarishvili L., Chanishvili T. Characterization of primary and secondary structure of DNA of staphylococcal bacteriophage Sb‐1. Questions in Virology. 1981;1:100–103. [Google Scholar]

- Andriashvili I., Kvachadze L., Vashakidze R., Adamia R., Chanishvili T. Molecular mechanism of DNA protection from restriction endonucleases in Staphylococcus aureus cells. Mol Gen Microbiol Virol. 1986;8:43–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayliffe G. The progressive intercontinental spread of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:74–79. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow P., Soothill J. Bacteriophage therapy and prophylaxis: rediscovery and renewed assessment of potential. Trends Microbiol. 1997;7:268–271. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruttin A., Brussow H. Human volunteers receiving Escherichia coli phage T4 orally: a safety test of phage therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2874–2878. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2874-2878.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton R.M. Phage therapy: past history and future prospects. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 1999;5:267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers H. Methicillin resistance in Staphylococci: molecular and biochemical basis and clinical implications. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:781–791. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanishvili N., Sharp R. Bacteriophage therapy: experience from the Eliava Institute, Georgia. Aust Microbiol. 2008;20:96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chanishvili N., Chanishvili T., Tediashvili M., Barrow P.A. Phages and their application against drug‐resistant bacteria. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2001;76:689–699. [Google Scholar]

- Chibani‐Chenooufi S., Dilman M., Marvin L., Rami‐Shojaei S., Brussow H. Lactobacillus plantarum bacteriophage LP65: a new member of the SPO1‐like genus of the family Myoviridae. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7069–7083. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7069-7083.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove S., Sakoulas G., Perencevich E., Schwaber M., Karchmer A., Carmeli Y. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin‐resistant and methicillin‐susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta‐analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:53–59. doi: 10.1086/345476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth D., Gulig P. Bacteriophages: potential treatment for bacterial infections. BioDrugs. 2002;16:57–62. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200216010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold B.C., Immergluck L.C., Maranan M.C., LAuderdale D.S., Gaskin R.E., Boyle‐Vavra S. Community‐acquired Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children with no identified predisposing risk. JAMA. 1998;279:593–598. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.8.593. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inal J. Phage therapy: a reappraisal of bacteriophages as antibiotics. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2003;51:237–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellenberger E. Vegetative bacteriophage and maturation of virus particles. Adv Virus Res. 1962;8:108–112. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klumpp J., Dorscht J., Lurz R., Bielmann R., Wieland M., Zimmer M. The terminally redundant, nonpermuted genome of Listeria bacteriophage A511: a model for the SPO1‐like Myoviruses of Gram‐positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:5753–5765. doi: 10.1128/JB.00461-08. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutateladze M., Adamia R. Phage therapy experience at the Eliava Institute. Med Mal Infect. 2008;38:426–430. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merril C., Biswas B., Carlton R., Jensen N., Creed G., Zullo S., Adhya S. Long‐circulating bacteriophage as antibacterial agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;8:3188–3192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merril C., Scholl D., Adhya S. Phage therapy. In: Calendar R., editor. University press; 2006. pp. 725–741. [Google Scholar]

- Montensinos I., Salido E., Delgado T., Cuervo M., Sierra A. Epidemiologic genotyping of Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus by pulsed field gel electrophoresis at a university hospital and comparison with antibiotyping and protein A and coagulase gene polymorphisms. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2119–2125. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.6.2119-2125.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey M., Chui L., Ismail J., Louie L., Murphy C., Chang M. Development a Canadian standardized protocol for subtyping methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus using pulsed field electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3481–3485. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.10.3481-3485.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Flaherty S., Coffey A., Edwards R., Meaney W., Fitzgerald J., Ross P. Genome of staphylococcal phage K: a new lineage of Myoviridae infecting gram‐positive bacteria with a low G‐C content. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2862–2871. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2862-2871.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees P., Fry B. The morphology of staphylococcal bacteriophage K and DNA metabolism in infected Staphylococcus aureus. J Gen Virol. 1981;53:293–307. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-53-2-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C. SPO1 and related bacteriophages. In: Soneshein A.L., Hoch J., Losick A., editors. ASM; 1993. pp. 813–829. . In Bacillus subtilis and Other Gram‐Positive Bacteria: Biochemistry, Physiology and Molecular Genetics. , and (eds). Washington DC, USA: , pp. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C., Casjens J.S., Cresawn S., Houtz J., Smith A., Ford M. The genome of Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage SP01. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:48–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.009. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenover F., Arbeit R., Goering R., Mikelsen P., Murray B., Persing D., Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by PFGE: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonenko T. 1973. Biochemical Methods for Viruses. Moscow: Medicina.

- Tikhonenko T., Koudelka I., Borishpolets Z. Concentration and purification of phages by column chromatography. J Microbiol. 1963;2:723–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarwood J., McCormick J., Paustian M., Orwin P., Kapur V., Schlievert P. Characterization and expression analysis of Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island 3. Implications for the evolution of staphylococcal pathogenicity islands. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13138–13147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]