Abstract

Objective

Vasa vasorum are angiogenic in advanced stages of human atherosclerosis and hypercholesterolemic mouse models. Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) is the predominant angiogenic growth factor in the adventitia and plaque of hypercholesterolemic low-density lipoprotein receptor–deficient/apolipoprotein B100/100 mice (DKO). FGF-2 seems to play a role in the formation of a distinct vasa vasorum network. This study examined the vasa vasorum structure and its relationship to FGF-2.

Methods and Results

DKO mice treated with saline, antiangiogenic recombinant plasminogen activator inhibitor-123 (rPAI-123), or soluble FGF receptor 1 were perfused with fluorescein-labeled Lycopersicon esculentum lectin. Confocal images of FGF-2–probed descending aorta adventitia show that angiogenic vasa vasorum form a plexus-like network in saline-treated DKO similar to the FGF-2 pattern of distribution. Mice treated with rPAI-123 and soluble FGF receptor 1 lack a plexus; FGF-2 and vasa vasorum density and area are significantly reduced. A perlecan/FGF-2 complex is critical for plexus stability. Excess plasmin produced in rPAI-123-treated DKO mice degrades perlecan and destabilizes the plexus. Plasmin activity and plaque size measured in DKO and DKO/plasminogen activator inhibitor-1−/− mice demonstrate that elevated plasmin activity contributes to reduced plaque size.

Conclusion

An FGF-2/perlecan complex is required for vasa vasorum plexus stability. Elevated plasmin activity plays a significant inhibitory role in vasa vasorum plexus and plaque development.

Keywords: adventitia, angiogenesis, atherosclerosis, fibroblast growth factor-2, vasa vasorum

Vasa vasorum are a network of microvasculature that originate primarily in the adventitia of large arteries. They supply oxygen and nutrients to the outer layers of the arterial wall which are beyond the limit of diffusion from the luminal surface.1 Vasa vasorum become angiogenic during atherosclerosis in humans2,3 and in mouse models of atherosclerosis.4–7 It is thought that they may contribute to the atherosclerotic disease process by facilitating plaque growth and serving as a conduit for inflammatory cell infiltration into the plaque;6,7 however, there is no direct evidence.

Kwon et al8 used micro-computerized tomography to identify 2 types of vasa vasorum in pig coronary arteries, which they named first and second order. The first order originates from large vessels and runs longitudinally between the adventitia and media of the main vessel. The second order consists of small vessels that branch from the first order and form circumferential arches around the vessel wall. Pigs with normal hearts have significantly greater first order vasa vasorum density and mean diameter compared with second order, whereas hypercholesterolemic pigs have more second-order vasa vasorum. The second-order vessels form a dense plexus in the adventitia, which is not found in healthy animals.8 Others, who used micro-computerized tomography to analyze vasa vasorum branching patterns in nondiseased pigs, show a dichotomous tree structure similar to the vasculature of systemic circulation. However, the branching lacks uniformity in that some continue to branch, whereas others discontinue the process.9 These data and additional studies10 indicate that vasa vasorum in healthy pigs behave like end arteries. The combined studies clearly suggest that the adventitial vasa vasorum can acquire an altered branching pattern in response to the disease process.

Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) belongs to the FGF family of growth factors. FGFs play a critical role in early embryonic development and a key role in adult neovascularization, inflammation, wound healing and tumor growth.11,12 They stimulate their activities primarily through binding interactions with FGF receptor (FGFR) 1 and FGFR2. FGF-2 can have other binding partners, to include syndecan-4,13 perlecan,14,15 betaglycan,16 fibrin, and fibrinogen.17,18 These interactions can influence FGF-2 activity and angiogenesis, protect FGF-2 from degradation, and prolong its effects on endothelial cells (ECs).17–19

Heparin-binding growth factors have a high affinity for heparan sulfate proteoglycan, particularly perlecan. In the case of FGF-2, the interaction with perlecan increases FGF-2 binding affinity for FGFRs and is required for FGFR phosphorylation and signal transduction.14,20,21

A truncated plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) isoform, recombinant PAI-123 (rPAI-123) has significant anti-angiogenic activity in vitro.22–24 It inhibits angiogenic vasa vasorum and promotes plaque regression in a low-density lipoprotein receptor–deficient (LDLR−/−)/apolipoprotein B100/100 (ApoB100/100) (DKO) mouse model of atherosclerosis.4,5 FGF-2 is the predominant angiogenic growth factor associated with adventitial vessels in hypercholesterolemic DKO mice.4 FGF-2 seems to play a role in the formation of a distinct vasa vasorum network which is not present in rPAI-123–treated DKO.4,5 The objective of this study was to further examine the unique vasa vasorum structure and its relationship to FGF-2.

Methods

Mouse Strain, Diet, and Treatment

LDLR−/−ApoB100/100 mice (B6; 129S-Apobtm2Sgy Ldlrtm1Her/J) (DKO) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (stock 003000). The LDLR−/−ApoB100/100/PAI-1−/− mouse strain (DKO/PAI-1−/−) was produced by crossing B6; 129S-Apobtm2Sgy Ldlrtm1Her/J with B6.129S2-Serpine1tm1Mlg/J (Jackson Laboratory, stock 002507). They were backcrossed for a minimum of 7 generations. Mice were fed either Paigen’s diet (PD) without cholate (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or normal chow diet (CH) for 20 weeks and received either rPAI-123 (5.4 μg/kg per day) or saline treatment for the last 6 weeks of the diet, as previously described.4 An adenoviral soluble FGFR1 (sFGFR1) construct (1×109 pfu), produced by Dr Simons laboratory25 (see online-only Data Supplement), was delivered by intraperitoneal injection into DKO mice at 14 weeks of PD. Mice were perfused and euthanized 10 days after delivery. (See the online-only Data Supplement for details regarding mouse models, rationale for use, treatment regimen, and experimental application.) Animal care and procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee and procedures outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health publication No. 86-23, 1985). All procedures were approved by the Dartmouth College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Perfusion

Mice were injected with 50 μL of heparin, followed by an injection of 0.1 mL ketamine/30 g of weight. They were euthanized and perfused with PBS, followed by 3.5% paraformaldehyde under 110 to 120 mm Hg pressure. Alternatively, mice were perfused as follows: (1) PBS, pH 7.2; (2) PBS containing 1% BSA and 1% fluorescein-labeled Lycopersicon esculentum lectin (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]-lectin) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA); (3) PBS containing 1% BSA; and (4) PBS containing calcium, magnesium, 1% BSA, 2% glutaraldehyde, and 1% paraformaldehyde.

Confocal Imaging of Vasa Vasorum and FGF-2 in Descending Aorta Whole Mounts

Mice were perfused with FITC-lectin. The descending aorta (DA) to the iliac bifurcation was surgically removed and probed for FGF-2 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). DA whole mounts were examined by confocal microscopy at ×20 and ×63 magnification, and z-stacks were collected as previously described.4,5 N=21 for DKO treatment groups and 8 for DKO/PAI-1−/− treatment groups.

Quantification of Confocal Images

Confocal z-stack slices were aligned in volumetric images. The resolution of the reconstructed volumetric data was increased by tri-linear interpolation for a detailed geometrical representation in 3-dimension. Microview software (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) was used to quantify the volume and area of FGF-2 and lectin. Quantitative values were obtained from the program generated isosurface. The 2 images were overlaid; N=4/group. Vessel diameter was measured in reconstructed confocal images using Microview software. N≥9/group.

Detection of FGF-2, Perlecan, and CD31 in the Adventitia of Descending Aortas

Thirty micron (μm) frozen sections of the DA from rPAI-123 or saline treated PD DKO mice were probed for FGF-2, perlecan (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and CD31 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) as previously described.4,5 N=3/group.

Detection of EC Death in the Vasa Vasorum

Propidium iodide (20 mg/kg) (Sigma) was delivered by retro orbital injection in 4 increments during a period of 15 minutes. Mice were perfused and euthanatized 20 minutes after the final injection. N=3/group.

Plasmin Activity Measurement

Plasmin activity, in 168 μg of plasma protein (sodium citrated collected), was measured in a Chromozym PL assay (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), as previously described.5 N=6/group.

Plaque Measurements

Image J software (National Institutes of Health) was used to measure plaque area in sequential 30 μm cross sections of the DA. Plaque volume was calculated by multiplying the plaque length times the average measured area. N=9/group.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with a 2-tailed indirect Student t test, 1-way ANOVA with a post hoc least significant difference test with or without repeated measures or with a χ2 test, as appropriate, using the SPSS 12.0.1 statistical software package.

Results

Vasa Vasorum Form a Plexus-Like Structure in Hypercholesterolemic Mice

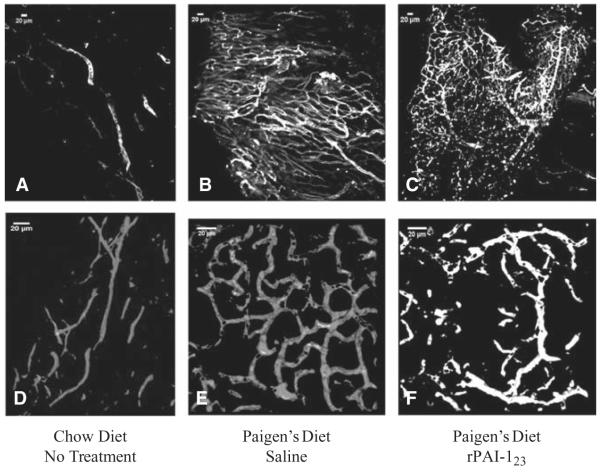

DKO mice, fed CH diet for 12 weeks and followed by 20 weeks of PD, were treated with either saline or rPAI-123 during the last 6 weeks of PD.4 Mice were perfused with FITC-lectin and confocal z-stack images of DA whole mounts were acquired (Figure 1). Chow-fed mice have detectable adventitial vessels, but they lack a branching pattern (Figure 1A and 1D). The vasa vasorum in PD-fed, saline-treated mice form a distinct, dense network (Figure 1B) of interconnecting vessels (Figure 1E). The plexus-like network appears to have been present in rPAI-123–treated PD mice (Figure 1C), but smaller vessels have regressed/collapsed (Figure 1F). The data show that the vasa vasorum acquire a different structure in response to the diet-induced disease process and many of the vessels become unstable with rPAI-123 treatment.

Figure 1.

Vasa vasorum form a plexus in hypercholesterolemic mice. Low-density lipoprotein receptor–deficient/apolipoprotein B100/100 (DKO), were fed normal chow diet (CH) or high-fat, high-cholesterol Paigen’s diet (PD) without cholate. The PD-fed mice develop plaque and angiogenic adventitial vasa vasorum. The PD mice were treated with saline or antiangiogenic recombinant plasminogen activator inhibitor-123 (rPAI-123) for the last 6 weeks of PD. Mice were perfused with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled lectin (white). Descending aorta whole mounts were imaged by confocal microscopy at ×20 magnification (A) CH; (B) PD, saline; (C) PD, rPAI-123 and at ×63 magnification; (D) CH; (E) PD, saline; (F) PD, rPAI-123. N=8 per group. Scale bar=20 μm. Note the plexus-like vascular network in the saline-treated PD mice (B and E), which is absent in the CH-fed mice (A and D) and collapsing in the rPAI-123–treated PD-fed mice (C and F).

FGF-2 Forms a Distinct Pattern in the Adventitia

Our previous studies indicate that FGF-2 is the predominant angiogenic growth factor in the DA adventitia of PD-fed mice.4 Further examination of FGF-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) protein expression in PD-fed mice perfused with FITC-lectin show that VEGF is mostly undetectable in the adventitia and in rare cases is found randomly distributed in the extracellular matrix/basement membrane (Figure II in the online-only Data Supplement). However, FGF-2 is abundantly expressed and forms a distinct pattern in the adventitia of saline-treated PD mice (Figure III in the online-only Data Supplement). The vessel density, diameter, and pattern of distribution are variable within the same adventitia (Figure IIIB in the online-only Data Supplement). Those differences appear to be dependent upon FGF-2 distribution (Figure IIIC in the online-only Data Supplement, right side versus left side).

FGF-2 Is Required for Vasa Vasorum Plexus Network

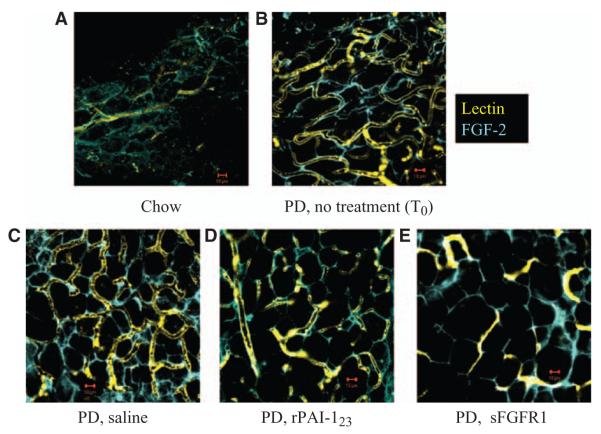

To determine whether FGF-2 is required for maintenance and stability of the vasa vasorum plexus, DA whole mounts from saline-treated, FITC-lectin perfused mice were compared with rPAI-123– or sFGFR1-treated mice. The rPAI-123 protein causes vasa vasorum collapse through a mechanism that increases plasmin activity,5 therefore it was used as a means of investigating FGF-2 distribution in relationship to loss of vasa vasorum. However, sFGFR1 is a decoy for FGFs25 and provides a means of demonstrating how removal of FGF affects vasa vasorum stability. Mice that were CH-fed for 32 weeks or CH-fed for 12 weeks and followed by 14 weeks of PD (T0) were used as controls.

FGF-2 in CH-fed mice is present in a diffuse pattern, lectin perfused vessels are few in number and do not form a network (Figure 2A). FGF-2 distribution is more defined in the T0 group, vessels are expanded and some form a pattern that is parallel to FGF-2 (Figure 2B). The likeness between the FGF-2 pattern of distribution and the vascular network pattern becomes even more distinct by 20 weeks of PD (Figure 2C). FGF-2 is significantly reduced after 6 weeks of rPAI-123 treatment and most vessels collapse/regress. The remaining vessels are aligned with FGF-2 and appear to have a larger diameter (Figure 2D). Similarly, FGF-2 and associated vessels in PD mice treated with sFGFR1 have regressed significantly (Figure 2E). These data demonstrate that FGF-2 is required for the vasa vasorum to maintain a stable plexus-like structure.

Figure 2.

Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) is required for vasa vasorum plexus network. Low-density lipoprotein receptor–deficient/apolipoprotein B100/100 mice (DKO) were fed normal chow diet (CH) for 32 weeks or CH for 12 weeks and thereafter by high-fat, high-cholesterol Paigen’s diet (PD) without cholate from 12 to 32 weeks of age. PD-fed mice received daily saline or antiangiogenic recombinant plasminogen activator inhibitor-123 (rPAI-123) injections for the last 6 weeks of PD or a single injection of adeno-soluble FGFR1 (sFGFR1, an FGF trap). At the end of treatment, mice were perfused with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled lectin (yellow), descending aorta whole mounts were probed for pro-angiogenic FGF-2 (blue), confocal z-stack images were collected at ×63 magnification. A, CH; (B) PD 14 weeks, no treatment, T0; (C) PD, saline treatment; (D) PD, rPAI-123 treatment; (E) PD, sFGFR1 treatment. Scale bar=10 μm. N=8/group. Note the defined FGF-2 pattern of distribution and expansion of the vasa vasorum in T0 (B) and saline treated (C) PD groups compared with the CH-fed (A) mice. Note the reduced FGF-2 expression corresponding to vasa vasorum collapse in rPAI-123 (D) and sFGFR (E) treated mice.

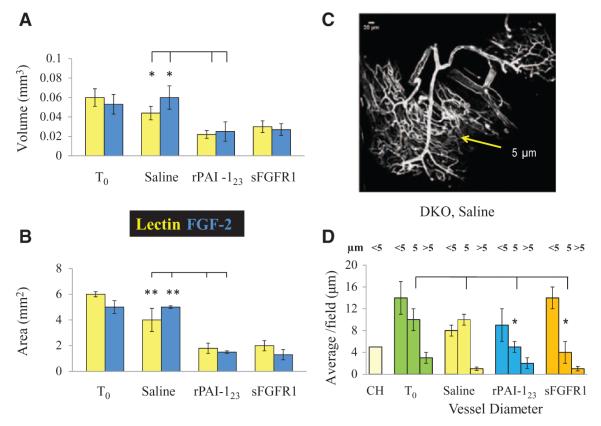

Quantitative Validation of Observed Differences Among Treatment Groups

The observed differences in FGF-2 and vasa vasorum among the treatment groups were verified in measurements of FGF-2 and lectin volume (Figure 3A), area (Figure 3B), and vessel diameter (Figure 3D) in confocal z-stack images reconstructed in Microview software. The measurements show that lectin volume is 2-fold greater in the PD-fed saline versus the PD-fed, rPAI-123 treatment group (saline, 0.04±0.007; rPAI-123, 0.02±0.004 mm3; P=0.03). FGF-2 volume is 2.4-fold greater in the saline-treated mice (saline, 0.059±0.02; rPAI-123, 0.025±0.01 mm3; P=0.05). Similarly, lectin area is 2.3-fold greater in PD-fed saline compared with rPAI-123–treated mice (saline, 4±0.2; rPAI-123, 1.75±0.4 mm2; P<0.001). FGF-2 area is 3.3-fold more in the mice treated with saline (saline, 4.9±0.5; rPAI-123, 1.48±0.14 mm2; P<0.001). The volume and area measured in sFGFR1-treated mice are comparable to rPAI-123.

Figure 3.

Quantification of fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) and vasa vasorum. Confocal z-stack images of descending aorta whole mounts from fluorescein isothiocyanate-lectin perfused, hypercholesterolemic low-density lipoprotein receptor–deficient/apolipoprotein B100/100 mice probed for FGF-2 were reconstructed in Microview software. A, Volume and (B) area measurements of pro-angiogenic FGF-2 (blue) and lectin (yellow) were obtained from software generated isosurface images at ×63 magnification. N=4 per group. C, Representative confocal image of the vasa vasorum vascular tree in DKO, saline-treated mice. Yellow arrow indicates region of 5 μm diameter vessels; (D) measurements of vessel diameter in reconstructed confocal images. N≥9/group. Note the reduced FGF-2 and lectin area and volume measurements in antiangiogenic recombinant plasminogen activator inhibitor-123 (rPAI-123) and soluble FGFR1 (sFGFR1) (FGF trap)-treated mice compared with T0 and saline-treated mice. Vessels in the 5 μm range are significantly less in rPAI-123– and sFGFR1-treated mice.

Confocal images show that the vasa vasorum in PD-fed DKO, saline-treated mice have a vascular tree with vessel branches of varied diameter (Figure 3C). Measurements of vessel diameter in all treatment groups fall into 3 categories, <5, 5, or >5 micron (μm). Those that comprise the plexus are 5 μm, whereas the main vessels from which the plexus branches are >5 μm. The numbers of vessels in the <5 or >5 μm ranges are not significantly different among all groups. However, the rPAI-123– and sFGFR1-treated mice have significantly fewer vessels with a 5 μm diameter compared with the T0 and saline-treated groups (T0, 10±2; saline, 10±1; rPAI-123, 5±1; sFGFR1, 4±2; P=0.008). These differences are consistent with the confocal images, which show that smaller vessels are the ones that collapse in response to rPAI-123 and sFGFR1 treatments.

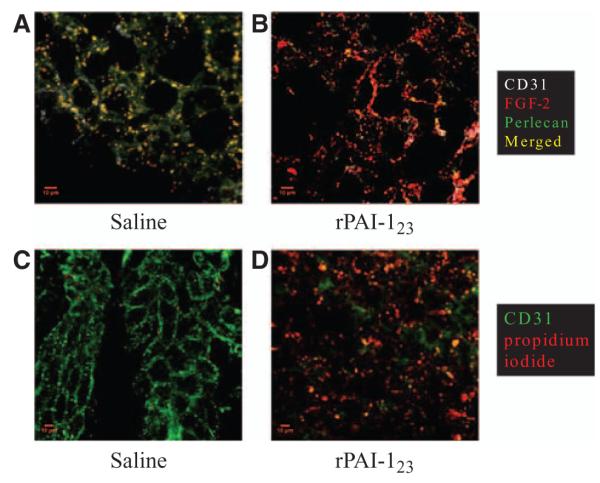

Potential FGF-2 Binding Partners

We considered that FGF-2 may require a binding partner to define its distinct pattern of distribution. Perlecan was a potential partner because it is known to bind FGF-2.26,27 Additionally, rPAI-123–stimulated increase in plasmin and matrix metalloproteinase-3 activities degrades perlecan, fibrin(ogen), and nidogen,5 all key components of the extracellular matrix/basement membrane. Degradation leads to loss of the supportive scaffold needed for angiogenic vessel stability and results in vessel collapse.5 Cross sections of the DA from saline and rPAI-123–treated, PD-fed DKO mice were probed for perlecan, FGF-2, and EC marker CD31 to visualize the distribution of perlecan and FGF-2 in relation to vessels in the adventitia. Colocalization of perlecan and FGF-2 was detected along with adventitial vessels in the saline-treated group (Figure 4A). However, mice treated with rPAI-123 show complete loss of perlecan, loss of most well-defined vessels and loss of a distinct FGF-2 pattern (Figure 4B). These data indicate that an FGF-2/perlecan complex is necessary for the distinct FGF-2 pattern of distribution. In the absence of the complex, the vessels collapse/regress. Propidium iodide was injected retro orbitally into mice from both treatment groups to determine whether loss of the complex results in EC death. After perfusion, DA whole mounts were probed for CD31. The saline-treated mice have an intact vasa vasorum plexus (Figure 4C), whereas ECs in the vasa vasorum of rPAI-123–treated mice are mostly dead (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) binds perlecan in the vasa vasorum. Descending aorta (DA) cross sections from hypercholesterolemic (Paigen’s diet-fed) low-density lipoprotein receptor–deficient/apolipoprotein B100/100 mice were probed for endothelial cell marker CD31 (white), pro-angiogenic FGF-2 (red), and perlecan (green), an FGF-2 binding partner, in (A) saline and (B) antiangiogenic recombinant plasminogen activator inhibitor (rPAI)-123 treatment groups (×63 magnification). Another set of mice from each group received a retro orbital injection of propidium iodide (red) before perfusion to detect non-viable cells. The DA was probed for CD31 (green) and whole mounts were imaged by confocal microscopy at ×40 magnification. C, Saline treated; (D) rPAI-123 treated. N=3 per group. Scale bar=10 μm. Note the colocalization of FGF-2 and perlecan associated with CD31+ cells in saline-treated mice (A) and the loss of perlecan in rPAI-123–treated mice (B). Propidium iodide+ cells (PI+) are absent in the vasa vasorum of saline-treated mice (C). An abundance of PI+ cells correspond with the absence of CD31+ cells in mice receiving rPAI-123 treatment (D).

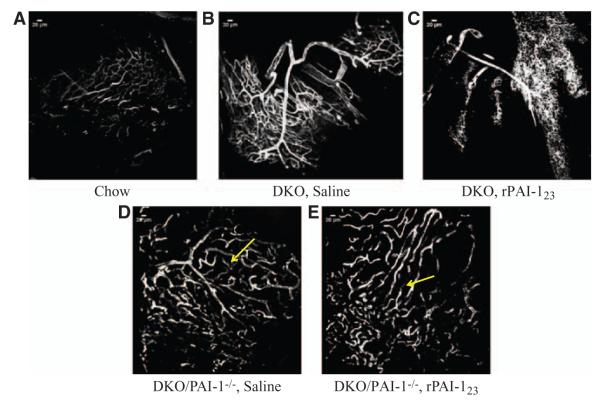

Plasmin Remodels the Angiogenic Vasa Vasorum

The effects of plasmin activity on vasa vasorum structure and stability were further examined by comparing PD-fed DKO with PD-fed DKO/PAI-1−/−mice. DKO/PAI-1−/− mice were selected, because PAI-1 inhibits the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin thus enabling a comparison with elevated plasmin activity in response to rPAI-123.

Reconstructed confocal images of the adventitial vasa vasorum in DA whole mounts show that the saline-treated, PD-fed DKO mice have a structural hierarchy; there is a large main vessel from which smaller vessels branch and they in turn branch to form a plexus (Figure 5B). The vasa vasorum in the DKO, rPAI-123 treatment group have large main vessels, but the plexus is collapsing/regressing (Figure 5C). The adventitial vessels in PD-fed DKO/PAI-1−/− mice treated with saline appear to have been an ordered arterial tree with smaller vessels between the larger branches (Figure 5D). The smaller vessels located between and connecting the main branches of the ordered arterial tree seem to be a plexus undergoing degradation/pruning. However, the rPAI-123–treated DKO/PAI-1−/− mice have large vessels that do not display a vascular tree or a plexus-like network (Figure 5E). The large vessels seem to be branches of the tree from which the plexus originates. Complete loss of the plexus network results in collapse of the larger vessels. The rPAI-123–treated DKO are able to maintain the structure of the larger branches (Figures 5C and 1C), which suggests that PAI-1 plays an important role in maintaining plexus stability.

Figure 5.

Plasmin remodels the angiogenic vasa vasorum. Atherosclerosis mouse model low-density lipoprotein receptor–deficient (LDLR−/−) apolipoprotein B (ApoB)100/100 (DKO) and plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 deficient LDLR−/−ApoB100/100/ PAI-1−/− (DKO/PAI-1−/−, plasmin in excess) mice were chow diet (CH)-fed for 32 weeks or CH for 12 weeks and thereafter by Paigen’s diet (PD) from 12 to 32 weeks of age and treated with saline or recombinant PAI-123 (rPAI-123) for the last 6 weeks of PD. Mice were perfused with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled lectin to detect plasmin effects on adventitial vessel structure. Descending aorta whole mounts were imaged by confocal microscopy at ×20 magnification. (A) DKO, CH; (B) DKO, PD, saline; (C) DKO, PD, rPAI-123; (D) DKO/PAI-1−/−, PD, saline; (E) DKO/ PAI-1−/−, PD, rPAI-123. Yellow arrows in Figure 6D and 6E indicate position of plexus. Scale bar=20 μm. Note the extensive plexus in PD-fed, saline-treated DKO that is collapsing in rPAI-123–treated mice. Plasmin in DKO/PAI-1−/− mice from both treatment groups appears to significantly remodel the plexus. N=8/group. Scale=20 μm.

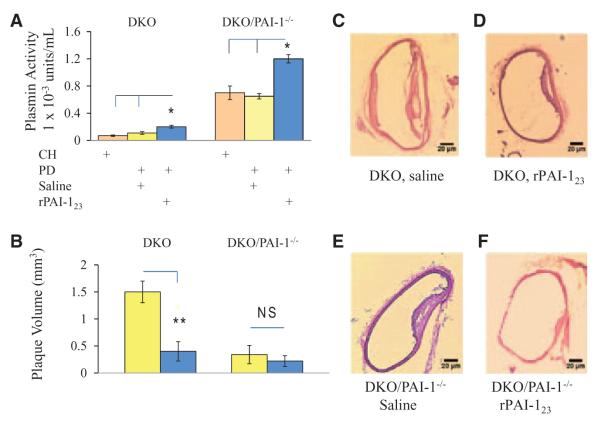

Increased Plasmin Activity Corresponds With Plaque Reduction

Because plasmin activity has a significant impact on vasa vasorum stability, its effect on plaque growth was analyzed in DKO and DKO/PAI-1−/− mice. Plasmin activity measured (Figure 6A) in rPAI-123–treated DKO mice is >2-fold its saline counterpart (rPAI-123, 0.2±0.01 × 10–3 versus saline, 0.1±0.01 × 10–3 units/mL; P<0.05). The activity in PD-fed, rPAI-123–treated DKO/PAI-1−/−mice is elevated 6-fold compared with rPAI-123–treated DKO (DKO/PAI-1−/−, rPAI-123, 1.2±0.06 × 10–3 units/mL; P<0.001). The plaque volume (Figure 6B) in PD-fed DKO, saline-treated mice is >3.8-fold its rPAI-123–treated counterpart (DKO, saline, 1.5±0.2 versus DKO, rPAI-123 0.4±0.2 mm3; P<0.003) and >7.5-fold DKO/PAI-1−/−, rPAI-123–treated mice (0.2±0.1 mm3; P<0.001). These data clearly indicate that elevated plasmin activity has a significant impact on plaque growth (Figure 6C–6F).

Figure 6.

Increased plasmin activity corresponds with plaque reduction. Hyper-cholesterolemic low-density lipoprotein receptor–deficient (LDLR)−/− apolipoprotein B (ApoB)100/100 (DKO) and plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 deficient LDLR−/−ApoB100/100/PAI-1−/− (DKO/PAI-1−/−, plasmin in excess) mice treated with recombinant PAI-123 (rPAI-123) or saline were examined for (A). Plasmin activity measured in plasma using a Chromozym PL assay. (B) Plaque volume measured in sequential descending aorta (DA) cross sections using Image J software. N=9/group. Representative images of plaque in hematoxylin and eosin-stained DA from each group are shown at ×10 magnification: (C) DKO, saline; (D) DKO, rPAI-123; (E) DKO/PAI-1−/−, saline; (F) DKO/PAI-1−/−, rPAI-123. Note that increased plasmin activity corresponds with reduced plaque size.

Discussion

This study shows, for the first time, the detailed structure of the vasa vasorum in murine atherosclerosis. The data further show that the vasa vasorum acquire a plexus-like structure in LDLR−/−/ ApoB100/100 mice that are fed a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet; the plexus contains the newly formed microvasculature. Our previous studies show that the vasa vasorum acquire an unusual pattern in hypercholesterolemic, saline-treated LDLR−/−ApoB100/100 mice and that FGF-2 seems to be associated with the vasa vasorum. This study advances our initial observations by showing that FGF-2 is required for the vasa vasorum to maintain stability of the plexus network. Moreover, we show that an FGF-2/perlecan complex is critical for specifying FGF-2 spatial distribution. Degradation of perlecan destabilizes the complex causing FGF-2 to lose its defined pattern of distribution and the vasa vasorum plexus destabilizes/regresses.

It remains to be determined whether FGF-2 provides a pattern for the vasa vasorum to form a plexus-like network or whether the vasa vasorum form a plexus, produce and release FGF-2 into the matrix. The images of DA whole mounts in chow-fed mice suggest that FGF-2 is present in a similar, but more diffuse pattern than the PD-fed mice. This occurs in the absence of an expanded vasa vasorum, which strongly suggests that FGF-2 provides the pattern for the vasa vasorum plexus. The more diffuse FGF-2 distribution may be due to differences in extracellular matrix/basement membrane composition or reduced matrix remodeling in non-hypercholesterolemic mice.

Clearly, the vasa vasorum expand and begin to form a plexus when the mice are fed a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet for 14 weeks. Our previous studies show that plaque has developed in the aortic arch and DA of DKO mice at 14 weeks of PD.4 The combined data indicate that development of the vasa vasorum plexus is part of the disease process. This is in keeping with the work of Kwon et al,8 who described a second-order vasa vasorum plexus in hypercholesterolemic pigs, but not in healthy animals.

FGF-2 has a short in vivo half-life of ≈2 to 4 minutes.28 It is highly susceptible to denaturation and degradation;29,30 its various binding partners provide FGF-2 with protection from degradation, thus prolonging its effects on ECs. Additionally, heparan sulfate proteoglycans can serve as an FGF-2 reservoir enabling higher than normal local concentrations of FGF-2 that prolong its stimulation of ECs.31 Because FGF-binding partners are at many-fold higher concentrations than FGF-2, it should be found complexed with a binding partner. The relative concentrations of FGF-2-binding partners may change because of physiological or pathophysiological changes to result in different FGF-2 activity.17,32 That is consistent with what we find for FGF-2 in the PD-fed DKO model. Its complex with perlecan is critical for maintaining the defined vasa vasorum structures, as demonstrated in saline-treated DKO mice. Loss of perlecan results in dispersal of FGF-2, collapse of the vessels and EC death, as shown in rPAI-123–treated mice.

Evidence of a perlecan/FGF-2 interaction does not rule out the possibility of other binding partners that may contribute to or alter the effect we observe for FGF-2 in PD-fed DKO mice. Changes in binding partners may occur at various stages of vasa vasorum development during the disease process. Others have reported that when an FGF-2-binding partner changes from a bound to soluble form it changes the activity of FGF-2.32

Altogether, this study demonstrates that the branching pattern of the adventitial vasa vasorum in DKO mice is similar to the findings of Kwon and Gossl. We demonstrate that the angiogenic microvasculature (5 μm lumen diameter) form a plexus in hypercholesterolemic mice, but not CH-fed mice, which is consistent with Kwon’s description of the second-order vasa vasorum structure in diseased pig coronary arteries. However, it should be noted that micro-computerized tomography images in Kwon’s studies relate more to arterioles with a lumen diameter >50 μm, whereas the adventitial plexus in DKO mice are at the capillary size. The plexus branches form a vascular tree structure. Degradation or pruning of the plexus in DKO/PAI-1−/− mice reveals a tree-like structure that is in keeping with Gossl’s prediction that the vasa vasorum in nondiseased pigs behave like functional end arteries not connected by a plexus.

It would not be surprising if FGF-2 provides guidance of the vasa vasorum into a plexus, because FGFs control guidance and branching patterns in the Drosophila trachea,33,34 vertebrate lungs, uteric system, and to some degree in the vascular system.35 Additionally, FGFs are known to serve as guidance cues for axons in Xenopus laevis retinal ganglion cells.36 It would not be unusual to find FGF-2 associated with the vasa vasorum in atherogenic mice as others have shown that it enhances the coupling of intimal hyperplasia and proliferation of vasa vasorum in injured rat arteries.37

Our previous studies identified a novel pathway by which rPAI-123 regulates plasmin activity. The elevated plasmin activity degrades key components of the basement membrane/extracellular matrix that are important for angiogenic vessel stability. In this study we further demonstrate that elevated plasmin activity corresponds with a reduction in plaque size. Elevated plasmin activity could potentially influence plaque growth through regression of the vasa vasorum and by degradation of the plaque matrix that contributes to the disease process. The rPAI-123–stimulated pathway that increases plasmin activity provides a mechanism for reducing plaque size that does not necessitate lipid lowering.

Altogether the data presented in this study demonstrate that the murine vasa vasorum and its supportive matrix constitute a dynamic environment. The vasa vasorum can readily expand or collapse in response to cues from the vessel wall.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure I

Supplemental Figure II. LDLR−/−/ApoB100/100 mice (DKO) were fed Paigen’s diet without cholate (PD) for 20 weeks. Mice were perfused with FITC-labeled lectin (green). Descending aorta whole mounts were probed for VEGF-A (red) and imaged by confocal microscopy at 40x magnification. Scale bar = 10 μm

Supplemental Figure III. FGF-2 forms a distinct pattern in the adventitia of hypercholesterolemic mice. DKO mice were fed PD for 14 weeks then perfused with FITC-labeled lectin. Whole mounted descending aortas were probed for FGF-2 and imaged by confocal microscopy. (A) FGF-2 probed adventitia; (B) FITC-lectin perfused vessels; (C) Overlap of FGF-2 and lectin. Red vertical line separates right from left side. Note the differences in FGF-2 and vessel patterns of distribution between right vs. left. Scale bar = 10 um

Acknowledgments

We thank Kenneth Orndorff, Optical Center Imaging Director, Norris Cotton Cancer Center Shared Resource, for his technical assistance in acquisition of confocal images.

Sources of Funding This study was funded by National Institutes of Health grants HL69948 (M.J. Mulligan-Kehoe) and HL53793 (M. Simons).

Footnotes

Disclosures None.

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://atvb.ahajournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.252544/-/DC1.

References

- 1.Heistad DD, Marcus ML. Role of vasa vasorum in nourishment of the aorta. Blood Vessels. 1979;16:225–238. doi: 10.1159/000158209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Brien ER, Garvin MR, Dev R, Stewart DK, Hinohara T, Simpson JB, Schwartz SM. Angiogenesis in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:883–894. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Finn AV, Gold HK, Tulenko TN, Wrenn SP, Narula J. Atherosclerotic plaque progression and vulnerability to rupture: angiogenesis as a source of intraplaque hemorrhage. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2054–2061. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000178991.71605.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drinane M, Mollmark J, Zagorchev L, Moodie K, Sun B, Hall A, Shipman S, Morganelli P, Simons M, Mulligan-Kehoe MJ. The anti-angiogenic activity of rPAI-1(23) inhibits vasa vasorum and growth of atherosclerotic plaque. Circ Res. 2009;104:337–345. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mollmark J, Ravi S, Sun B, Shipman S, Buitendijk M, Simons M, Mulligan-Kehoe MJ. Antiangiogenic activity of rPAI-1(23) promotes vasa vasorum regression in hypercholesterolemic mice through a plasmin-dependent mechanism. Circ Res. 2011;108:1419–1428. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.246249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moulton KS, Heller E, Konerding MA, Flynn E, Palinski W, Folkman J. Angiogenesis inhibitors endostatin or TNP-470 reduce intimal neovascularization and plaque growth in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 1999;99:1726–1732. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.13.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moulton KS, Vakili K, Zurakowski D, Soliman M, Butterfield C, Sylvin E, Lo KM, Gillies S, Javaherian K, Folkman J. Inhibition of plaque neovascularization reduces macrophage accumulation and progression of advanced atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4736–4741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730843100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon HM, Sangiorgi G, Ritman EL, Lerman A, McKenna C, Virmani R, Edwards WD, Holmes DR, Schwartz RS. Adventitial vasa vasorum in balloon-injured coronary arteries: visualization and quantitation by a microscopic three-dimensional computed tomography technique. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:2072–2079. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gössl M, Rosol M, Malyar NM, Fitzpatrick LA, Beighley PE, Zamir M, Ritman EL. Functional anatomy and hemodynamic characteristics of vasa vasorum in the walls of porcine coronary arteries. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2003;272:526–537. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gõssl M, Malyar NM, Rosol M, Beighley PE, Ritman EL. Impact of coronary vasa vasorum functional structure on coronary vessel wall perfusion distribution. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H2019–H2026. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00399.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murakami M, Simons M. Fibroblast growth factor regulation of neovascularization. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:215–220. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282f97d98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horowitz A, Tkachenko E, Simons M. Fibroblast growth factor-specific modulation of cellular response by syndecan-4. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:715–725. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aviezer D, Hecht D, Safran M, Eisinger M, David G, Yayon A. Perlecan, basal lamina proteoglycan, promotes basic fibroblast growth factor-receptor binding, mitogenesis, and angiogenesis. Cell. 1994;79:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma B, Handler M, Eichstetter I, Whitelock JM, Nugent MA, Iozzo RV. Antisense targeting of perlecan blocks tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1599–1608. doi: 10.1172/JCI3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andres JL, DeFalcis D, Noda M, Massagué J. Binding of two growth factor families to separate domains of the proteoglycan betaglycan. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5927–5930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahni A, Altland OD, Francis CW. FGF-2 but not FGF-1 binds fibrin and supports prolonged endothelial cell growth. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1304–1310. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahni A, Francis CW. Plasmic degradation modulates activity of fibrinogen-bound fibroblast growth factor-2. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1271–1277. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saksela O, Moscatelli D, Sommer A, Rifkin DB. Endothelial cell-derived heparan sulfate binds basic fibroblast growth factor and protects it from proteolytic degradation. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:743–751. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.2.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segev A, Aviezer D, Safran M, Gross Z, Yayon A. Inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by a novel fibroblast growth factor receptor antagonist. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:232–241. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00447-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yayon A, Klagsbrun M, Esko JD, Leder P, Ornitz DM. Cell surface, heparin-like molecules are required for binding of basic fibroblast growth factor to its high affinity receptor. Cell. 1991;64:841–848. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90512-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drinane M, Walsh J, Mollmark J, Simons M, Mulligan-Kehoe MJ. The anti-angiogenic activity of rPAI-1(23) inhibits fibroblast growth factor-2 functions. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33336–33344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulligan-Kehoe MJ, Kleinman HK, Drinane M, Wagner RJ, Wieland C, Powell RJ. A truncated plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 protein blocks the availability of heparin-binding vascular endothelial growth factor A isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49077–49089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulligan-Kehoe MJ, Wagner R, Wieland C, Powell R. A truncated plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 protein induces and inhibits angiostatin (kringles 1-3), a plasminogen cleavage product. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8588–8596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murakami M, Nguyen LT, Zhuang ZW, Zhang ZW, Moodie KL, Carmeliet P, Stan RV, Simons M. The FGF system has a key role in regulating vascular integrity. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3355–3366. doi: 10.1172/JCI35298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knox S, Merry C, Stringer S, Melrose J, Whitelock J. Not all perlecans are created equal: interactions with fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 2 and FGF receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14657–14665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vincent TL, McLean CJ, Full LE, Peston D, Saklatvala J. FGF-2 is bound to perlecan in the pericellular matrix of articular cartilage, where it acts as a chondrocyte mechanotransducer. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;15:752–763. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whalen GF, Shing Y, Folkman J. The fate of intravenously administered bFGF and the effect of heparin. Growth Factors. 1989;1:157–164. doi: 10.3109/08977198909029125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gospodarowicz D, Cheng J. Heparin protects basic and acidic FGF from inactivation. J Cell Physiol. 1986;128:475–484. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041280317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gospodarowicz D, Neufeld G, Schweigerer L. Fibroblast growth factor: structural and biological properties. J Cell Physiol Suppl. 1987;(Suppl 5):15–26. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041330405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Presta M, Maier JA, Rusnati M, Ragnotti G. Basic fibroblast growth factor is released from endothelial extracellular matrix in a biologically active form. J Cell Physiol. 1989;140:68–74. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041400109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Presta M, Dell’Era P, Mitola S, Moroni E, Ronca R, Rusnati M. Fibroblast growth factor/fibroblast growth factor receptor system in angiogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:159–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ribeiro C, Ebner A, Affolter M. In vivo imaging reveals different cellular functions for FGF and Dpp signaling in tracheal branching morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2002;2:677–683. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sutherland D, Samakovlis C, Krasnow MA. branchless encodes a Drosophila FGF homolog that controls tracheal cell migration and the pattern of branching. Cell. 1996;87:1091–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81803-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horowitz A, Simons M. Branching morphogenesis. Circ Res. 2008;103:784–795. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.181818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webber CA, Chen YY, Hehr CL, Johnston J, McFarlane S. Multiple signaling pathways regulate FGF-2-induced retinal ganglion cell neurite extension and growth cone guidance. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;30:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edelman ER, Nugent MA, Smith LT, Karnovsky MJ. Basic fibroblast growth factor enhances the coupling of intimal hyperplasia and proliferation of vasa vasorum in injured rat arteries. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:465–473. doi: 10.1172/JCI115607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure I

Supplemental Figure II. LDLR−/−/ApoB100/100 mice (DKO) were fed Paigen’s diet without cholate (PD) for 20 weeks. Mice were perfused with FITC-labeled lectin (green). Descending aorta whole mounts were probed for VEGF-A (red) and imaged by confocal microscopy at 40x magnification. Scale bar = 10 μm

Supplemental Figure III. FGF-2 forms a distinct pattern in the adventitia of hypercholesterolemic mice. DKO mice were fed PD for 14 weeks then perfused with FITC-labeled lectin. Whole mounted descending aortas were probed for FGF-2 and imaged by confocal microscopy. (A) FGF-2 probed adventitia; (B) FITC-lectin perfused vessels; (C) Overlap of FGF-2 and lectin. Red vertical line separates right from left side. Note the differences in FGF-2 and vessel patterns of distribution between right vs. left. Scale bar = 10 um