Abstract

Objective

Psychotic depression (PD) is a highly debilitating condition, which needs intensive monitoring. However, there is no established rating scale for evaluating the severity of PD. The aim of this analysis was to assess the psychometric properties of established depression rating scales and a number of new composite rating scales, covering both depressive and psychotic symptoms, in relation to PD.

Method

The psychometric properties of the rating scales were evaluated based on data from the Study of Pharmacotherapy of Psychotic Depression.

Results

A rating scale consisting of the 6-item Hamilton melancholia subscale (HAM-D6) plus five items from the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), named the HAMD-BPRS11, displayed clinical validity (Spearman coefficient of correlation between HAMD-BPRS11 and Clinical Global Impression - Severity (CGI-S) scores = 0.79 - 0.84), responsiveness (Spearman correlation coefficient between change in HAMD-BPRS11 and Clinical Global Impression -Improvement (CGI-I) scores = -0.74 - -0.78) and unidimensionality (Loevinger coefficient of homogeneity = 0.41) in the evaluation of PD. The HAM-D6 fulfilled the same criteria, whereas the full 17-item Hamilton depression scale failed to meet criteria for unidimensionality.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that the HAMD-BPRS11 is a more valid measure than pure depression scales for evaluating the severity of PD.

Keywords: Affective disorders, Depression, Psychoses, Psychometrics

Introduction

Psychotic depression (PD) is currently classified as a subtype of depression in both the 10th revision of the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) (1) and the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text revision (DSM-IV-TR) (2). This distinction between PD and non-psychotic depression (non-PD) will not be changed in the upcoming DSM-5, and there have been no reports suggesting that this should be the case for the ICD-11 (3).

PD is characterized by the presence of delusions and/or hallucinations in addition to depressive symptoms. Typical cases display severe anhedonia, loss of interest, psychomotor retardation, and are tormented by hallucinations/delusions with typical themes of worthlessness, guilt, disease or impending disaster (4). A number of studies have indicated that PD differs from non-PD (3). These differences have been documented for potential precipitating factors (5-7), underlying biology (8-11), symptomatology beyond the psychotic symptoms (12, 13), long-term prognosis (14-19) and responsiveness to psychopharmacological treatment and electroconvulsive therapy (20-30). The difference in treatment response between patients with PD and those with non-psychotic depression has led to a series of clinical trials, investigating response to various psychopharmacological treatment regimens specifically among patients with PD (28, 31-33). These studies have shown fairly consistently that PD responds better to the combination of an antipsychotic and an antidepressant than to monotherapy with either class of drugs (34, 35).

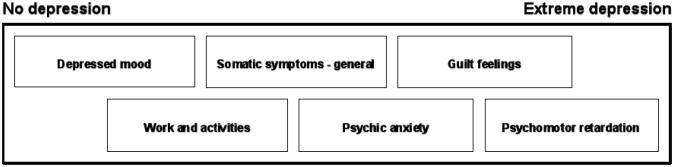

When conducting clinical trials, in any branch of medicine, choosing a valid outcome estimate is essential. In psychiatry, where laboratory tests reflecting illness severity are not available, systematic clinical assessment must be the basis for outcome measures, as emphasized in the discipline of “clinimetrics” (36, 37). Therefore, targeted clinical assessment has been operationalized through the construction of a large number of psychiatric rating scales, which allow quantification of the psychopathology of various syndromes (38). Such rating scales need to meet two essential criteria: they must be clinically valid (the scale items cover the clinical syndrome and map the severity of the syndrome appropriately) and psychometrically unidimensional (the symptoms represented by the scale-items appear in an orderly fashion as the severity of the syndrome increases, such that scoring on lower prevalence items presupposes scoring on higher prevalence items). Only when these two criteria are met can the scores on the individual items of the scale be added to a clinically and mathematically meaningful total score (38, 39). In depression, the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D17) (40) has become a de-facto standard and has been used as outcome measure in approximately 95% of all controlled trials of SSRIs in patients with major depression (41). However, there is a growing body of literature suggesting that this scale suffers from important weaknesses as a quantitative measure of depression. First and foremost, it displays poor clinical validity, as the total score does not always reflect the global severity of depressive states as perceived by experienced psychiatrists (42). Secondly, the HAM-D17 is not psychometrically unidimensional (43-45). Finally, the occurrence of common adverse effects of some antidepressant drugs such as sedation or increased appetite/weight gain are rated as improvement in depressive symptoms on the scale (it contains three items covering insomnia and two items on loss of appetite/weight loss), while actually representing significant, long term problems for many patients (44, 46, 47). The HAM-D17 does however contain a subscale, that fulfills the criteria of both clinical validity and unidimensionality and which doesn't mistake occurrence of adverse effects for improvement in depression. This subscale consists of six items (depressed mood, work and activities, somatic symptoms – general, psychic anxiety, guilt feelings and psychomotor retardation) and is commonly referred to as “the melancholia subscale” or the HAM-D6 (42, 43, 45, 48). Since the symptoms represented by the HAM-D6 items appear in an orderly fashion as the severity of illness increases among depressed patients, the scale can be used as a “ruler”, where the total score indicates the severity of depression (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The “depression ruler”.

The figure shows how the six individual items from the melancholia subscale (HAM-D6) of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale relates to the severity of depression. Since the items appear orderly as the severity of illness increases (unidimensionality), the individual item scores can be added to a total score, which is a valid measure for the severity of depression. Modified version of figure 4.2 in Bech P., Clinical Psychometrics, 2012, Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, West-Sussex, UK.

In addition to, or maybe because of, its superior clinical validity and unidimensionality, the HAM-D6 also seems to be a more sensitive measure of the antidepressant effect of psychotropic drugs in placebo-controlled trials (45, 47, 49-51).

In clinical studies of PD, choosing a rating scale is particularly challenging due to the clinical significance of both the psychotic and the depressive domains of the syndrome (4). In the majority of trials involving patients with PD, various versions of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (most often the HAM-D17) have been used as the primary outcome measure (28, 31-33). However, neither the clinical nor the psychometric validity of the HAM-D17 has been established in relation to PD. Another argument against using the HAM-D17 scale as the primary measure of the severity of PD is that it lacks content validity (and therefore also clinical validity) regarding the defining psychotic symptoms of the disorder, since only two delusions (delusions of guilt and somatic delusions) can be rated specifically and there are no items pertaining to hallucinations. In some trials this problem has been addressed by including an additional dichotomous rating of the psychotic symptoms and making their absence part of the response/remission criteria (31, 52). Such an “all or nothing” approach is not ideal since there is a wide body of literature suggesting that psychotic symptoms are probably not categorical but dimensional in nature, and may cause distress even at milder levels (53-57). Nevertheless, a rating scale that captures both the depressive and psychotic dimensions of PD is not available.

Aims of the study

The present study addressed the apparent lack of evaluation of the rating scales used in PD. First, we aimed at investigating psychometric properties of the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 in relation to PD. Second, we wished to assess whether a rating scale covering both psychotic and depressive symptoms could be a valid measure of the severity of PD. Specifically, we addressed the following questions:

Is the factor structure of HAM-D17 in psychotic depression similar to that of non-psychotic depression?

Are the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 clinically valid and responsive measures of the severity of psychotic depression?

Are the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 psychometrically unidimensional measures of the severity of psychotic depression?

Which items on the BPRS correlate with the severity of delusions and hallucinations in psychotic depression?

Is a composite rating scale consisting of the HAM-D6 plus BPRS items covering delusions/hallucinations a valid measure of the severity of psychotic depression?

Material and methods

Data from the Study of the Pharmacotherapy of Psychotic Depression (STOP-PD) was used for this analysis. As reported elsewhere, STOP-PD is a twelve-week, double-blind, randomized trial comparing the remission rates among PD patients treated with either Olanzapine+Placebo or Olanzapine+Sertraline (31). The trial included a total of 259 patients who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depressive disorder with psychotic features (58) and presented with a minimum total score of 21 on the GRID-HAMD (a modified version of the HAM-D17, which takes both the frequency and the intensity of symptoms into account) (59). Inclusion also required the presence of at least one delusion, rated as minimum 2 on one of the conviction items of the Delusional Assessment Scale (DAS) (57) and a severity score of at least 3 (when there is no more than a transient ability to consider the implausibility of an irrational belief) on the delusion item of the Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) (60). The outcome measures included the HAM-D17, the Clinical Global Impressions -severity of illness (CGI-S) and -improvement (CGI-I) subscales (61), and the 18-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (62). Throughout the study, HAM-D17 ratings were performed by trained research assistants whereas the DAS, SADS, CGI-S, CGI-I and the BPRS were administered by psychiatrists who were not blinded to the HAM-D17 scores (31).

Psychometric analysis

Question 1:The baseline HAM-D17 data for all 259 patients was subjected to Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (63, 64) The PCA represents the classical “British” approach to factor analysis, which tests whether the items of a scale display positive intercorrelation (the first principal component), and whether the scale contains a bi-directional component pointing to the existence of two distinct factors of the syndrome being rated (the second principal component). This method is opposed to the “American” approach, which identifies several factors by means of “orthogonal” or “oblique” rotation (38). In this study we adhere to the British tradition, as we consider it to be less intrusive and more in line with Occam's razor. In other words, if the dual factors identified by the PCA make sense from a clinical perspective, there is no need to introduce further factors (38). The PCA was conducted by means of the SAS statistical package (version 9.00, 2002).

Question 2:The clinical validity of the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 in relation to PD was evaluated by Spearman correlation analysis of the HAM-D17 / HAM-D6 total scores versus CGI-S scores at week 4, 8 and 12. Similarly, responsiveness was tested by Spearman correlation of the difference in HAM-D17 / HAM-D6 total scores from baseline to week 4, 8 and 12 respectively, versus corresponding CGI-I scores at week 4, 8 and 12. The analysis of responsiveness was based on the last observation carried forward method and all correlations were made using the SAS statistical package (version 9.00, 2002).

Question 3:The evaluation of the psychometric unidimensionality of the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 in relation to PD was performed by Mokken analysis (65). This non-parametric item response theory model is based on Loevinger's coefficient of homogeneity, which is calculated as the weighted average of the individual item coefficients (66). The Loevinger coefficient of homogeneity expresses whether the items of a scale are ordered according to their relationship to the severity of the syndrome being measured, i.e. that scorings on lower prevalence items presuppose scorings on higher prevalence items. When this is the case, the item scores are additive and the total score is a sufficient statistic for the severity of the syndrome (66). As suggested by Mokken, a Loevinger coefficient of homogeneity ≥0.40 is considered a demonstration of unidimensionality (65). The Mokken analysis was based on HAM-D17 ratings from week 4 in order to have sufficient variance in the total scores. The rating on item 13 (general somatic) was multiplied by 2 to obtain a score-range of 0-4 on all HAM-D6 items. This approach has been used in similar studies and therefore facilitates the comparison with other patient populations (44, 47). The Mokken analysis was performed using the dedicated MSP program (67).

Question 4:To determine which items from the BPRS carried information regarding delusions and hallucinations in PD, we conducted a Spearman correlation analysis of the ratings on each individual BPRS-item (score range 1-7) versus the SADS delusion (score range 3-7) and hallucination (score range 1-3) ratings at baseline.

Question 5:Based on the answers of Question 1-4, we constructed a number of composite rating scales covering both depressive and psychotic symptoms. Due to the apparent favourable psychometric properties of the HAM-D6 in PD (see results section), the composite scales were constructed by adding the BPRS items, which displayed significant correlation with the SADS items regarding delusions/hallucinations, to the HAM-D6. The BPRS items were added one by one in order of decreasing Spearman correlation coefficients (motor retardation and anxiety were not included due to overlap with the HAM-D6) giving rise to a total of seven rating scales named HAMD-BPRSx where the suffix ranging from 7-13 represents the total number of items:

HAMD-BPRS7: HAM-D6+ hallucinatory behaviour

HAMD-BPRS8: HAM-D6+ hallucinatory behaviour + unusual thought content

HAMD-BPRS9: HAM-D6+ hallucinatory behaviour + unusual thought content + suspiciousness

HAMD-BPRS10: HAM-D6+ hallucinatory behaviour + unusual thought content + suspiciousness + emotional withdrawal

HAMD-BPRS11: HAM-D6+ hallucinatory behaviour + unusual thought content + suspiciousness + emotional withdrawal + blunted affect

HAMD-BPRS12: HAM-D6+ hallucinatory behaviour + unusual thought content + suspiciousness + emotional withdrawal + blunted affect + somatic concern

HAMD-BPRS13: HAM-D6+ hallucinatory behaviour + unusual thought content + suspiciousness + emotional withdrawal + blunted affect + somatic concern + uncooperativeness

These composite scales were subsequently tested for clinical validity, psychometric unidimensionality and responsiveness using the methods described above (Question 2+3). For the correlation analyses regarding clinical validity and responsiveness the BPRS item scores (from 1-7) were converted to a score between 0 and 4 according to this formula: (BPRS score - 1) × 2/3. For the Mokken analysis, which requires data on a numeric scale, the BPRS scores were converted as follows: 1=0, 2-3=1, 4-5=2, 6=3, 7=4. In all analyses of the seven composite scales, the rating on Hamilton item 13 (general somatic) was multiplied by 2.

Results

The 259 participants in the STOP-PD trial were recruited at four academic psychiatric facilities in the United States and Canada. They had a mean age of 58.8 (SD=17.7) years and 35.9% of them were males. The mean HAM-D17 total score at baseline was 29.8 (SD=5.3). The proportion of participants remaining in the trial over the 12 weeks was as follows: week 2 = 91.5%, week 4 = 81.5%, week 6 = 67.2%, week 8 = 62.2%, week 10 = 58.3%, and week 12 = 54.8%. The full demographic description of the participants is reported in the primary publication on the STOP-PD data (31).

Question 1:The results of the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the HAM-D17 baseline data are shown in table 1.

Table 1. Principal component analysis of the 17-item Hamilton depression rating scale (HAM-D17) based on baseline data from the Study of Pharmacotherapy of Psychotic Depression (STOP-PD) (n=259).

| HAM-D17 items | First principal component Loadings | Second principal component Loadings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Depressed mood* | 0.29 | 0.20 |

| 2 | Guilt feelings* | 0.00 | 0.52 |

| 3 | Suicide | 0.20 | 0.55 |

| 4 | Sleep initial | 0.40 | -0.06 |

| 5 | Sleep middle | 0.48 | -0.31 |

| 6 | Sleep late | 0.18 | -0.24 |

| 7 | Work and activities* | 0.37 | 0.09 |

| 8 | Psychomotor retardation* | 0.20 | 0.09 |

| 9 | Agitation | 0.08 | -0.50 |

| 10 | Psychic anxiety* | 0.39 | -0.27 |

| 11 | Somatic anxiety | 0.44 | 0.25 |

| 12 | Appetite | 0.54 | -0.05 |

| 13 | Somatic symptoms, general* | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| 14 | Sex | 0.19 | 0.55 |

| 15 | Hypochondriasis | 0.50 | -0.08 |

| 16 | Weight loss | 0.61 | -0.16 |

| 17 | Insight | -0.09 | -0.23 |

Eigenvalue of the first principal component = 2.11. Eigenvalue of the second principal component = 1.64.

Items defining the 6-item melancholia subscale (HAM-D6) of the 17-item Hamilton depression rating scale.

The analysis identified a general factor (the first principal component) with an eigenvalue of 2.11 and positive loadings on all 17 items apart from the item of guilt (0.00) and insight (-0.09). The second principal component was bi-directional with an eigenvalue of 1.64. The distribution of the negative versus positive loadings for this bidirectional factor is also shown in table 1. All items of the HAM-D6, with the exception of psychic anxiety (-0.27), had positive loadings on this second factor.

Question 2:The results of the correlation analyses investigating the clinical validity and responsiveness of the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 are shown in table 2.

Table 2. Clinical validity and responsiveness of the 17-item Hamilton depression rating scale (HAM-D17) and the 6-item melancholia subscale (HAM-D6).

| Clinical validity | |||

| Week 4 (n=185) | Week 8 (n=144) | Week 12 (n=135) | |

| HAM-D17 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.82 |

| HAM-D6 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.82 |

| Responsiveness | |||

| Week 4 (LOCF) | Week 8 (LOCF) | Week 12 (LOCF) | |

| HAM-D17 | -0.80 | -0.79 | -0.81 |

| HAM-D6 | -0.77 | -0.80 | -0.83 |

Above - clinical validity: Spearman correlation analysis for the total scores on the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 versus Clinical Global Impression – Severity (CGI-S) scores at week 4, 8 and 12. Below - responsiveness: Spearman correlation analysis for the change in total scores from baseline to week 4, 8 and 12 on the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 versus Clinical Global Impression – Improvement (CGI-I) scores at week 4, 8 and 12 (n=252 - Last observation carried forward (LOCF)). All correlations were statistically significant (p<0.001).

The Spearman coefficients reflecting clinical validity were above 0.74 for both the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 for week 4, 8 and 12. Similarly, the coefficients representing responsiveness were below -0.77 for both rating scales in the same period.

Question 3:The Loevinger coefficients of homogeneity obtained by the Mokken analysis are shown in table 3 alongside results from two treatment studies using the HAM-D17 as primary outcome measure among patients with non-psychotic depression (44, 45).

Table 3. Analysis of psychometric validity/unidimensionality of the 17-item Hamilton depression rating scale (HAM-D17) and the 6-item melancholia subscale (HAM-D6).

| Loevinger coefficients of homogeneity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| STOP-PD (n=210) | STAR*D [45] (n=2323) | Licht et al. 2005 [44] (n=1459) | |

| HAM-D17 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.28 |

| HAM-D6 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.49 |

Mokken analysis of the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 scores at week 4 across three studies: the Study of Pharmacotherapy of Psychotic Depression (STOP-PD), the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) and “Validation of the Bech-Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale and the Hamilton Depression Scale in patients with major depression; is the total score a valid measure of illness severity?” (Licht et al 2005). The results are expressed as Loevinger coefficients of homogeneity, where values ≥ 0.40 indicate unidimensionality.

The values from the present study were 0.30 for the HAM-D17 and 0.50 for the HAM-D6 respectively, which should be interpreted in relation to the a priori defined threshold for unidimensionality of 0.40 (see methods above) (65).

Question 4:The results of the correlation between ratings on the individual BPRS items versus the SADS delusion and hallucination ratings at baseline are shown in table 4.

Table 4. Correlation between Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) item scores and Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) delusions/hallucinations scores.

| BPRS – Items | Spearman coefficients | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SADS Delusions | SADS Hallucinations | ||

| 1 | Somatic concern | 0.15 * | 0.02 |

| 2 | Anxiety | 0.18 ** | -0.14 * |

| 3 | Emotional withdrawal | 0.21 *** | 0.10 |

| 4 | Conceptual disorganization | 0.10 | -0.01 |

| 5 | Guilt feelings | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| 6 | Tension | 0.12 | 0.07 |

| 7 | Mannerisms and posturing | 0.01 | -0.00 |

| 8 | Grandiosity | -0.02 | 0.05 |

| 9 | Depressive mood | 0.06 | -0.01 |

| 10 | Hostility | -0.02 | 0.03 |

| 11 | Suspiciousness | 0.27 *** | 0.13 * |

| 12 | Hallucinatory behaviour | 0.11 | 0.87 *** |

| 13 | Motor retardation | 0.16 ** | 0.03 |

| 14 | Uncooperativeness | 0.13 * | 0.06 |

| 15 | Unusual thought content | 0.28 *** | 0.26 *** |

| 16 | Blunted affect | 0.19 ** | 0.13 * |

| 17 | Excitement | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| 18 | Confusion | 0.00 | 0.05 |

Spearman correlation analysis for BPRS item scores versus the SADS item scores regarding delusions and hallucinations at baseline (n=259). SADS delusion score range = 3-7. SADS hallucination score range = 1-3. Score range on all BPRS items = 1-7.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

A total of nine items were significantly correlated with at least one of the two SADS items.

Question 5:The results of the analysis regarding the clinical validity and responsiveness of the seven composite rating scales are shown in table 5.

Table 5. Clinical validity and responsiveness of the HAMD-BPRS composite rating scales.

| Clinical validity | |||

| Week 4 (n=185) | Week 8 (n=144) | Week 12 (n=134) | |

| HAMD-BPRS7 | 0.74 | 0.81 | 0.82 |

| HAMD-BPRS8 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| HAMD-BPRS9 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| HAMD-BPRS10 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| HAMD-BPRS11 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| HAMD-BPRS12 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| HAMD-BPRS13 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| Responsiveness | |||

| Week 4 (LOCF) | Week 8 (LOCF) | Week 12 (LOCF) | |

| HAMD-BPRS7 | -0.74 | -0.78 | -0.79 |

| HAMD-BPRS8 | -0.75 | -0.79 | -0.81 |

| HAMD-BPRS9 | -0.74 | -0.79 | -0.79 |

| HAMD-BPRS10 | -0.75 | -0.79 | -0.79 |

| HAMD-BPRS11 | -0.74 | -0.78 | -0.78 |

| HAMD-BPRS12 | -0.75 | -0.77 | -0.76 |

| HAMD-BPRS13 | -0.75 | -0.76 | -0.76 |

Above - clinical validity: Spearman correlation analysis for the total scores on the seven HAMD-BPRS composite rating scales versus Clinical Global Impression – Severity (CGI-S) scores at week 4, 8 and 12. Below - responsiveness: Spearman correlation analysis for the change in rating scale total scores from baseline to week 4, 8 and 12 versus Clinical Global Impression – Improvement (CGI-I) scores at CGI-I at week 4, 8 and 12 (n=252 - Last observation carried forward (LOCF)). All correlations were statistically significant (p<0.001).

The Spearman coefficients reflecting clinical validity were above 0.74 for all composite rating scales for week 4, 8 and 12. The corresponding coefficients for responsiveness were all below -0.74 in the same period. There was relatively little difference in the size of the correlation coefficients among the various composite scales. The Mokken analysis yielded the following Loevinger coefficients of homogeneity: HAMD-BPRS7=0.44, HAMD-BPRS8=0.43, HAMD-BPRS9=0.40, HAMD-BPRS10=0.40, HAMD-BPRS11=0.41, HAMD-BPRS12=0.37, HAMD-BPRS13=0.37, which should again be interpreted in relation to the threshold for unidimensionality of 0.40.

Discussion

This secondary analysis of the data from STOP-PD investigated psychometric aspects of psychotic depression with special focus on the HAM-D17, the HAM-D6, and seven constructed composite scales covering both depressive and psychotic symptoms. The answers to the five main research questions were as follows:

1. Is the factor structure of HAM-D17 in psychotic depression similar to that of non-psychotic depression?

To give an answer to this question we ran a principal component analysis, which tests whether the items of a scale display positive intercorrelation (the first principal component) and whether the scale contains a bi-directional factor, pointing to the existence of two distinct dimensions of the syndrome being rated (the second principal component). Our analysis of HAM-D17 ratings of patients with PD confirmed the presence of a general factor (eigenvalue = 2.11). We also identified a second principal component (eigenvalue = 1.64) with a bidirectional factor structure. The distinction between items with negative and positive loadings was largely consistent with studies of patients with non-psychotic depression, where the HAM-D17 items grouped into “pure” depressive symptoms (the items of the HAM-D6) and neurovegetative symptoms (appetite and sleep problems) (38, 45). However, in the present analysis, psychic anxiety did not group among the other items from the HAM-D6. On the other hand, the item of somatic anxiety had a loading similar to that of the core items of depression. There is often a rather high correlation between psychic and somatic anxiety that may explain this finding. The overall results of our principal component analysis are largely consistent with those of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study (45).

2. Are the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 clinically valid and responsive measures of the severity of psychotic depression?

The results of the correlation analyses assessing the clinical validity and the responsiveness of the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 indicated that both scales were able to capture both the severity of PD and the clinical improvement during treatment. The fact that the correlation coefficients for the HAM-D6 scores versus both CGI-S (clinical validity) and CGI-I (responsiveness) scores were practically identical to those obtained for the HAM-D17 was somewhat surprising since the latter was used to define primary outcome in STOP-PD. However, when interpreted in the light of the only clinical validation of the HAM-D17 performed to date (42), where the six items from the HAM-D6 were identified as those carrying actual information on depressive severity, it makes perfect sense.

3. Are the HAM-D17 and the HAM-D6 psychometrically unidimensional measures of the severity of psychotic depression?

The Mokken analysis yielded Loevinger coefficients of homogeneity of 0.30 for the HAM-D17 and 0.50 for the HAM-D6 respectively. These values are practically identical to those obtained in larger trials involving patients with non-psychotic depression. Licht et al. reported coefficients of 0.28 for the HAM-D17 and 0.48 for the HAM-D6 based on 1459 patients (44), whereas Bech et al. reported values of 0.32 and 0.48 respectively based on 2323 patients from the STAR*D trial (45). The threshold for unidimensionality is generally considered to be 0.40 (65). Consequently, as in the case of non-PD, the HAM-D6 and not the HAM-D17 appeared to be a sufficient statistic, i.e., the total score is a valid measure for the severity of PD.

4. Which items on the BPRS correlate with the severity of delusions and hallucinations in psychotic depression?

Our analysis identified nine BPRS items, which correlated significantly with at least one of the two SADS items of delusions and hallucinations. These items were used to construct a total of seven composite rating scales, which were then tested for clinical validity, psychometric validity and responsiveness.

5. Is a composite rating scale consisting of the HAM-D6 plus BPRS items covering delusions/hallucinations a valid measure of the severity of psychotic depression?

According to the results of our analyses of the seven composite rating scales we believe that the HAMD-BPRS11 displays the ideal balance between psychometric unidimensionality, content validity, clinical validity and responsiveness. Of the unidimensional scales (Loevinger coefficient above 0.40), the HAMD-BPRS11 is the scale with the most items (content validity), the highest agreement with CGI-S (clinical validity) and could therefore represent a superior alternative to pure depression scales in relation to PD. Notably, the BPRS items included in the HAMD-BPRS11 are almost the same as those constituting the psychotic subscale of the BRPS (unusual thought content, hallucinations, conceptual disorganization and suspiciousness) (62). However, among the STOP-PD participants, scores on the emotional withdrawal and blunted affect (common features of depression) but not conceptual disorganization (a more typical feature of schizophrenia) items, correlated with the SADS items of delusions and hallucinations. Thus, this is well in line with a general clinical impression of patients with PD (4).

Limitations to this analysis warrant a mention. Most importantly, the original STOP-PD trial was not designed to answer the research questions posed in this study. Therefore, our evaluation of the rating scales in terms of clinical validity and responsiveness, based on CGI-S and CGI-I scores, is not state-of-the-art for a dedicated psychometric validation study. In such a study, the HAM-D17/BPRS ratings and the CGI ratings respectively should be performed by independent teams of raters. The global assessment (CGI) should be made by highly experienced psychiatrists (gold standard), whereas the ratings on the HAM-D17/BPRS could be performed by less experienced doctors or other health professionals (42). In the STOP-PD, the CGI and BPRS ratings were indeed performed by psychiatrists, whereas the HAM-D17 ratings were conducted by trained research assistants with documented reliability (31). Consequently, for a study, which was not designed for a psychometric analysis, STOP-PD has many qualities that justify our use of the data for this purpose.

There is a lack of consensus on how to measure the severity of PD and the majority of treatment studies only considers improvement in depression and do not take change in psychotic symptoms into account in their definitions of remission or response (4, 68). The authors of a recent meta-analysis comparing the effect of antidepressant or antipsychotic monotherapy versus combination treatment emphasize these problems in their conclusion: “To facilitate better comparability across trials, ideally, the psychiatric field should agree on… standardized outcomes of response, remission, and relapse in patients with psychotic depression” (34). The results of our analysis of the STOP-PD data indicate that the HAMD-BPRS11 rating scale consisting of items covering both the depressive and the psychotic dimension of PD may possess higher psychometric validity compared to the most commonly used depression scale, namely the HAM-D17.

Significant outcomes.

A composite rating scale consisting of the 6-item Hamilton melancholia subscale (HAM-D6) plus five items from the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), named the HAMD-BPRS11, displayed both clinical and psychometric validity in the measurement of the severity and treatment response of psychotic depression.

The 17-item Hamilton depression scale (HAM-D17) is not a unidimensional measure for the severity of psychotic depression. I.e. the total score on this scale is not a meaningful way of expressing the severity of the condition.

Limitations.

The Study of the Pharmacotherapy of Psychotic Depression (STOP-PD) was not designed to answer the research questions posed in this study.

The ratings on the HAM-D17 and the BPRS were not performed by the same raters (trained research assistants and psychiatrists respectively).

The validity of the HAMD-BPRS11 has not been confirmed in independent samples.

Acknowledgments

The STOP-PD received funding by the US Public Health Service - MH 62446, MH 62518, MH 62565, and MH 62624; National Center for Research Resources - M01-RR024153, RR000056, CTSC UL1RR024996; the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) - MH069430, MH067710, and P30 MH068368; The NIMH supported the STOP-PD and participated in its implementation through the UO1 mechanism. They did not participate in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of study data or in the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript. A data safety monitoring board at the NIMH provided data and safety monitoring during the STOP-PD. Eli Lilly donated olanzapine and Pfizer donated sertraline and placebo/sertraline for the STOP-PD. Neither Eli Lilly nor Pfizer participated in the design, implementation, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data in the STOP-PD or in the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript. Clinical Trial Registration: NCT00056472

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: S.D. Østergaard has received speaking fees, consultant honoraria and travel support from Janssen-Cilag until April 2011. Furthermore, he has received travel support at one occasion in 2010 from Bristol Myers Squibb. A.J. Rothschild has received grant support from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Cyberonics, Takeda, and St. Jude Medical and has served as a consultant to Allergan, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Shire Pharmaceuticals, and Sunovian. A.J. Flint has received grant support from the NIMH, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and Lundbeck and has received honoraria from Janssen-Ortho, Lundbeck Canada, and Pfizer Canada. B.H. Mulsant currently receives research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the US National Institute of Health (NIH), Bristol-Myers Squibb (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial), and Pfizer (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial). He directly own stocks of General Electric (less than $5,000). Within the past three years, he has also received some travel support from Roche. B. Meyers receives research support from the NIMH. He is receiving medication donated by Pfizer and Eli Lilly for his NIMH trial. During the last three years he has provided legal consultation to AstraZeneca and research consultation for Forest Laboratories. E.M. Whyte has received research support from the NIMH, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the Department of Defense (DOD) and through a Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grant from Fox Learning Systems / National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). P. Bech and C.M. Ulbricht declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Diagnostic criteria for research. Vol. 1993 WHO; Geneva: The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Vol. 2000 Washington DC: Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostergaard SD, Rothschild AJ, Uggerby P, Munk-Jorgensen P, Bech P, Mors O. Considerations on the ICD-11 Classification of Psychotic Depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2012;81:135–144. doi: 10.1159/000334487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothschild AJ. Clinical Manual for Diagnosis and Treatment of Psychotic Depression. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; Washington DC, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostergaard SD, Petrides G, Dinesen PT, et al. The Association between Physical Morbidity and Subtypes of Severe Depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2013;82:45–52. doi: 10.1159/000337746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostergaard SD, Waltoft BL, Mortensen PB, Mors O. Environmental and familial risk factors for psychotic and non-psychotic severe depression. J Affect Disord. 2013;147:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domschke K, Lawford B, Young R, et al. Dysbindin (DTNBP1) - A role in psychotic depression? J Psychiatr Res. 2010;45:588–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson JC, Davis JM. DST studies in psychotic depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1497–1503. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Posener JA, Debattista C, Williams GH, Chmura Kraemer H, Kalehzan BM, Schatzberg AF. 24-Hour monitoring of cortisol and corticotropin secretion in psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:755–760. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.8.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cubells JF, Price LH, Meyers BS, et al. Genotype-controlled analysis of plasma dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity in psychotic unipolar major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:358–364. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyers BS, Alexopoulos GS, Kakuma T, et al. Decreased dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity in unipolar geriatric delusional depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:448–452. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maj M, Pirozzi R, Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Bartoli L. Phenomenology and prognostic significance of delusions in major depressive disorder: a 10-year prospective follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1411–1417. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostergaard SD, Bille J, Soltoft-Jensen H, Lauge N, Bech P. The validity of the severity-psychosis hypothesis in depression. J Affect Disord. 2012;140:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coryell W, Leon A, Winokur G, et al. Importance of psychotic features to long-term course in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:483–489. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothschild AJ, Samson JA, Bond TC, Luciana MM, Schildkraut JJ, Schatzberg AF. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and 1-year outcome in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;34:392–400. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90184-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson J, Horwath E, Weissman MM. The validity of major depression with psychotic features based on a community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:1075–1081. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360039006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vythilingam M, Chen J, Bremner JD, Mazure CM, Maciejewski PK, Nelson JC. Psychotic depression and mortality. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:574–576. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park MH, Kim TS, Yim HW, et al. Clinical characteristics of depressed patients with a history of suicide attempts: results from the CRESCEND study in South Korea. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:748–754. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181f4aeac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ostergaard SD, Bertelsen A, Nielsen J, Mors O, Petrides G. The association between psychotic mania, psychotic depression and mixed affective episodes among 14,529 patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;147:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spiker DG, Kupfer DJ. Placebo response rates in psychotic and nonpsychotic depression. J Affect Disord. 1988;14:21–23. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glassman AH, Roose SP. Delusional depression. A distinct clinical entity? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:424–427. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290058006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charney DS, Nelson JC. Delusional and nondelusional unipolar depression: further evidence for distinct subtypes. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138:328–333. doi: 10.1176/ajp.138.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schatzberg AF, Rothschild AJ. Psychotic (delusional) major depression: should it be included as a distinct syndrome in DSM-IV? Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:733–745. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.6.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson WH, Khan A, Orr WW., JR Delusional depression. Phenomenology, Neuroendocrine function, and tricyclic antidepressant response. J Affect Disord. 1984;6:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(84)80008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spiker DG, Weiss JC, Dealy RS, et al. The pharmacological treatment of delusional depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:430–436. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.4.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown RP, Frances A, Kocsis JH, Mann JJ. Psychotic vs. nonpsychotic depression: comparison of treatment response. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1982;170:635–637. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan CH, Janicak PG, Davis JM, Altman E, Andriukaitis S, Hedeker D. Response of psychotic and nonpsychotic depressed patients to tricyclic antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrides G, Fink M, Husain MM, et al. ECT remission rates in psychotic versus nonpsychotic depressed patients: a report from CORE. J ECT. 2001;17:244–253. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200112000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loo CK, Mahon M, Katalinic N, Lyndon B, Hadzi-pavlovic D. Predictors of response to ultrabrief right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy. J Affect Disord. 2011;130:192–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birkenhager TK, Pluijms EM, Lucius SA. ECT response in delusional versus non-delusional depressed inpatients. J Affect Disord. 2003;74:191–195. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyers BS, Flint AJ, Rothschild AJ, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of olanzapine plus sertraline vs olanzapine plus placebo for psychotic depression: the study of pharmacotherapy of psychotic depression (STOP-PD) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:838–847. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wijkstra J, Burger H, Van Den Broek WW, et al. Treatment of unipolar psychotic depression: a randomized, double-blind study comparing imipramine, venlafaxine, and venlafaxine plus quetiapine. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121:190–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothschild AJ, Williamson DJ, Tohen MF, et al. A double-blind, randomized study of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for major depression with psychotic features. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:365–373. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000130557.08996.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farahani A, Correll CU. Are antipsychotics or antidepressants needed for psychotic depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials comparing antidepressant or antipsychotic monotherapy with combination treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:486–496. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r07324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leadholm AK, Rothschild AJ, Nolen WA, Bech P, Munk-Jorgensen P, Ostergaard SD. The treatment of psychotic depression: is there consensus among guidelines and psychiatrists? J Affect Disord. 2013;145:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feinstein AR. T. Duckett Jones Memorial Lecture. The Jones criteria and the challenges of clinimetrics. Circulation. 1982;66:1–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.66.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fava GA, Tomba E, Sonino N. Clinimetrics: the science of clinical measurements. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:11–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bech P. Clinical Psychometrics. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford; UK: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stochl J, Jones PB, Croudace TJ. Mokken scale analysis of mental health and well-being questionnaire item responses: a non-parametric IRT method in empirical research for applied health researchers. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bech P. Pharmacological treatment of depressive disorders:a review. In: Maj M, Sartorius N, editors. Depressive disorders WPA series evidence and experience in psychiatry. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bech P, Gram LF, Dein E, Jacobsen O, Vitger J, Bolwig TG. Quantitative rating of depressive states. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1975;51:161–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1975.tb00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bech P, Allerup P, Gram LF, et al. The Hamilton depression scale. Evaluation of objectivity using logistic models. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1981;63:290–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1981.tb00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Licht RW, Qvitzau S, Allerup P, Bech P. Validation of the Bech-Rafaelsen Melancholia Scale and the Hamilton Depression Scale in patients with major depression; is the total score a valid measure of illness severity? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;111:144–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bech P, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Rush AJ. Factor structure and dimensionality of the two depression scales in STAR*D using level 1 datasets. J Affect Disord. 2011;132:396–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K. The UKU side effect rating scale. A new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and a cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1987;334:1–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb10566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bech P. Is the antidepressive effect of second-generation antidepressants a myth? Psychol Med. 2010;40:181–186. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709006102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bech P. The three-fold Hamilton Depression Scale: an editorial comment to Isacsson G, Adler M. Randomized clinical trials underestimate the efficacy of antidepressants in less severe depression (1) Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125:423–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bech P, Boyer P, Germain JM, et al. HAM-D17 and HAM-D6 sensitivity to change in relation to desvenlafaxine dose and baseline depression severity in major depressive disorder. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2010;43:271–276. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1263173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bech P, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Rush AJ. Outcomes on the pharmacopsychometric triangle in bupropion-SR vs. buspirone augmentation of citalopram in the STAR*D trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125:342–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bech P, Allerup P, Larsen ER, Csillag C, Licht R. Escitalopram versus nortriptyline: how to let the clinical GENDEP data tell us what they contained. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127:328–329. doi: 10.1111/acps.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wijkstra J, Lijmer J, Balk FJ, Geddes JR, Nolen WA. Pharmacological treatment for unipolar psychotic depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:410–415. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.010470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Preti A, Bonventre E, Ledda V, Petretto DR, Masala C. Hallucinatory experiences, delusional thought proneness, and psychological distress in a nonclinical population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:484–491. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31802f205e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Langer AI, Cangas AJ, Serper M. Analysis of the multidimensionality of hallucination-like experiences in clinical and nonclinical Spanish samples and their relation to clinical symptoms: implications for the model of continuity. Int J Psychol. 2011;46:46–54. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2010.503760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johns LC. Hallucinations in the general population. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7:162–167. doi: 10.1007/s11920-005-0049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johns LC, Van Os J. The continuity of psychotic experiences in the general population. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21:1125–1141. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meyers BS, English J, Gabriele M, et al. A delusion assessment scale for psychotic major depression: Reliability, validity, and utility. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:1336–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams JB, Kobak KA, Bech P, et al. The GRID-HAMD: standardization of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23:120–129. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f948f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spitzer R, Endicott J. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. 3rd. Biometrics Research Dept; New York State Psychiatric Institute: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guy W. US Department of Health, Education and Welfare pub no(AMD) NIMH; Rockville, MD, USA: 1976. Clinical Global Impressions Scale. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology; pp. 76–338. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hotelling H. Rotations in psychology and the statistical revolution. Science. 1942;95:504–507. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hotelling H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables with principal components. J Educ Psychol. 1933;24:417–441. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mokken RJ. Theory and Practice of Scale Analysis. Mouton; Berlin, Germany: p. 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Loevinger J. Objective tests as instruments of psychological theory. Biol Psychiatry. 1957;3:635–694. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Molenaar IW, Debels P, Sijtsna K. User's Manual MSP, a Program for Mokken Scale Analyses for Polytomous Items (Version 3.0) ProGAMMA, Groeningen; The Netherlands: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wijkstra J, Lijmer J, Balk F, Geddes J, Nolen WA. Pharmacological treatment for psychotic depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD004044. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004044.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]