Abstract

Background

Cigarette smoking is an established risk factor for adult myeloid leukemia, particularly acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but less is known about the nature of this association and effects of smoking cessation on risk.

Methods

In a large population-based case-control study of myeloid leukemia that included 414 AML and 185 chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cases and 692 controls ages 20–79 years, we evaluated risk associated with cigarette smoking and smoking cessation using unconditional logistic regression methods and cubic spline modeling.

Results

AML and CML risk increased with increasing cigarette smoking intensity in men and women. A monotonic decrease in AML risk was observed with increasing time since quitting, whereas for CML, the risk reduction was more gradual. For both AML and CML, among long-term quitters (≥30 years), risk was comparable to non-smokers.

Conclusions

Our study confirms the increased risk of myeloid leukemia with cigarette smoking and provides encouraging evidence of risk attenuation following cessation.

Keywords: Leukemia, Acute myeloid leukemia, Chronic myeloid leukemia, Cigarette smoking, Smoking cessation

1. Introduction

Myeloid leukemia is a heterogeneous group of acute and chronic hematopoietic malignancies of the myeloid lineage; the two most common subgroups are AML and CML [1]. In the United States, approximately 13,800 and 5400 individuals are diagnosed annually with AML and CML, respectively, while 10,200 and 600 will die [2]. With the dismal survival for AML, prevention is a priority. Benzene, radiation and prior chemotherapy exposure are well-established risk factors for AML, although collectively they account for a small number of cases; obesity may also contribute to risk [3–5]. Importantly, cigarette smoking may account for as much as 17% of myeloid leukemias [6]. Nevertheless, while cigarette smoking has been considered an established risk factor for myeloid leukemia for over a decade [7], the exact nature of this association in unclear (e.g. few studies have evaluated sex and leukemia classification differences, and even fewer have considered potential benefits of smoking cessation on risk). Using data from a large population-based case–control study of AML and CML, we examined effect modifiers, explored the shape and nature of the dose–response relationship, and for AML, evaluated associations by cytogenetic subtypes, for both cigarette smoking and smoking cessation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Recruitment and enrollment have been described [8,9]. Incident cases were identified through the rapid case ascertainment system of the Minnesota Cancer Surveillance System from June 2005 to November 2009. Eligible cases were Minnesota residents, able to understand English or Spanish, and diagnosed between ages 20 and 79 years with AML, CML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), or other myeloid leukemias. A total of 907/1178 pathologically confirmed cases were referred (230 died soon after diagnosis, 41 were not referred due to physician/patient refusal). Of the 907 referred, 833 were contacted, and 673 enrolled (83% cooperation rate; 57% overall participation rate) [10]. Non-participation reasons included participant refusal (16%) and ineligibility (3%). Cases were classified by disease subclassification; AML was further subclassified by 2001 World Health Organization (WHO) and French-American-British (FAB) systems [11,12]. All classifications involved central pathology report review including cytochemical and flow cytometric immunophenotypic data; microscopic glass side review was performed as necessary. Cytogenetic results were also centrally reviewed and integrated with the pathologic diagnoses, per 2001 WHO guidelines. Final classification resulted in 420 AML (3 additional cases enrolled but died before questionnaire completion), 186 CML, and 64 CMML/ other myeloid leukemia.

Controls were identified using the Minnesota State Driver’s License/identification card list, which includes almost all adults less than 85 years of age living in Minnesota. Controls must have (a) been alive at contact time; (b) resided in Minnesota; (c) been between 20 and 79 years; (d) understood English or Spanish; and e) had no prior myeloid leukemia diagnosis. Controls were frequency matched to cases on age in deciles. Of 1200 potentially eligible controls identified, 1020 were successfully contacted, and 701 (77% cooperation rate; 64% overall response rate) agreed to enroll [10]. Reasons for non-participation included refusal (21%) and ineligibility (10%).

2.2. Data collection

Tobacco and alcohol use was obtained from the self-administered questionnaire, as were demographics, physical activity, medication use, medical and reproductive history, family cancer history, occupational history, and history of various job and home chemical exposures. To account for disease-related changes in smoking status, cigarette smoking history was assessed up to two years prior to questionnaire completion for participants who smoked cigarettes for at least six months during their lifetime. For comparison with previous studies and evaluation of effect modification, participant smoking was categorized as “never versus ever smokers” and “never, former, or current smokers”. Additional variables combined smoking intensity (usual cigarettes/ day prior to quitting or 2 years prior to questionnaire completion) and status or duration: never smokers, former smoker <1 pack/day, former smoker ≥1 pack/day, current smoker <1 pack/day, and current smoker ≥1 pack/day. For duration, a similar variable was created using ≤20 and >20 years in place of former and current smokers. Pack-years (packs/day times years smoked) were also calculated to explore dose response. Smoking cessation included current smokers, former smokers who quit smoking <15 years ago, 15–29 years ago, and ≥30 years ago, and never smokers; dose-response among ever smokers was evaluated using years since quitting as a continuous variable. If a former smoker had not quit for at least a year, 0.5 years was assigned. All current smokers were assigned ‘0’. While other tobacco products (e.g., pipe, cigar, snuff, and chewing tobacco) were queried, frequency and intensity were not assessed; they were not considered further.

2.3. Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 statistical software (Cary, NC). Unconditional logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for smoking main effects. Demographic variables (Table 1) including sex, race, income, education level, body mass index (BMI), alcohol consumption, occupational benzene exposure, occupational/therapeutic radiation exposure, and chemotherapy were evaluated and retained as confounders if they altered the effect estimate by ≥10%; the frequency matching variable (age) was included as a continuous variable. Analyses were repeated stratified by sex, age (<60 vs. ≥60 years), leukemia subtype, and AML WHO subtypes; effect modification was evaluated by Wald test. WHO subtypes were evaluated using categories defined by Vardiman et al. [12], with further delineation by differentiation pattern for the “not otherwise categorized” subtypes (Table 2).

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of adult myeloid leukemia cases and population-based controls.

| Controls (N = 692) N (%) |

AML cases (N=414) N (%) |

CML cases (N= 185) N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 20–29 | 45 (7) | 26 (6) | 12 (6) |

| 30–39 | 52 (8) | 32 (8) | 15 (8) |

| 40–49 | 101 (15) | 63 (15) | 33 (18) |

| 50–59 | 155 (22) | 88 (21) | 48 (26) |

| 60–69 | 201 (29) | 126 (30) | 47 (25) |

| 70–79 | 138 (20) | 79 (19) | 30 (16) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 354 (51) | 170 (41) | 79 (43) |

| Male | 338 (49) | 244 (59) | 106 (57) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 663 (96) | 388 (94) | 171 (92) |

| Other | 29 (4) | 26 (6) | 14 (8) |

| Incomea | |||

| Up to $40,000 | 253 (37) | 148 (37) | 79 (43) |

| $40,00–$80,000 | 275 (40) | 162 (40) | 64 (35) |

| Over $80,000 | 154 (23) | 95 (23) | 39 (21) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabitating | 507 (73) | 311 (75) | 121 (65) |

| Other | 185 (27) | 103 (25) | 64 (35) |

| Education | |||

| ≤High school graduate | 229 (33) | 118 (29) | 66 (36) |

| Some post HS | 236 (34) | 159 (38) | 55 (40) |

| College graduate | 227 (33) | 137 (33) | 64 (36) |

| BMIb | |||

| Normal/underweight | 224 (33) | 94 (23) | 41 (22) |

| Overweight | 238 (35) | 146 (35) | 59 (32) |

| Obese | 227 (33) | 173 (42) | 84 (46) |

| Current alcohol usec | |||

| Heavy | 20 (3) | 19 (5) | 7 (4) |

| Moderate | 183 (27) | 76 (19) | 38 (21) |

| Light | 200 (29) | 132 (33) | 52 (29) |

| Abstainer | 276 (41) | 179 (44) | 85 (47) |

| Benzene/solvent exposure | |||

| No | 642 (93) | 339 (82) | 163 (88) |

| Yes | 47 (7) | 73 (18) | 22 (12) |

| Radiation exposure | |||

| No | 671 (97) | 386 (93) | 174 (95) |

| Yes | 18 (3) | 27 (7) | 10 (5) |

| Chemotherapy exposure | |||

| No | 679 (99) | 383 (93) | 177 (96) |

| Yes | 10 (1) | 30 (7) | 7 (4) |

Income may include retirement income.

BMI based on weight 2 years prior to questionnaire completion.

Current alcohol use was defined as follows: abstainer (<1 drink/month); light (<3 drinks/week); moderate(<3 drinks/day); heavy(3+ drinks/day).

Table 2.

Distribution of 414 AML cases by 2001 WHO classification.

| WHO subtypes | Frequency (subtype total) |

|---|---|

| AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities | (91) |

| AML with t(8,21)(q22;q22),(AML1/ETO) | 17 |

| AML with inv(16)(p13q22) or t(16;16)(p13;q22),(CBFβ/MYH11) |

14 |

| Acute promyelocytic leukemia with t(15;17)(q22;q12),(PML/RARα) |

48 |

| AML with 11q23 (MLL) abnormalities) | 12 |

| AML with multilineage dysplasia | 40 |

| AML and myelodysplastic syndromes, therapy related | 13 |

| AML without a specific lineage of differentiationa,b | (160) |

| AML, minimally differentiated | 19 |

| AML without maturation | 54 |

| AML with maturation | 83 |

| AML with a specific differentiation patterna | (91) |

| Acute myelomonocytic leukemia | 39 |

| Acute monoblastic/monocytic leukemia | 33 |

| Acute erythroid leukemia | 17 |

| Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia | 0 |

| Acute basophilic leukemia | 0 |

| Acute panmyelosis with myelofibrosis | 1 |

| Myeloid sarcoma | 1 |

| NOS | 19 |

AML, not otherwise categorized subtypes were further delineated by differentiation pattern for analyses.

Category includes 4 additional AML cases of ambiguous lineage.

Dose-response between leukemia and pack-years smoked and time since quitting was evaluated using restricted cubic splines. The number and position of knots were determined by minimizing the Akaike’s information criterion (AIC), allowing for comparison of multiple models while penalizing complexity. To prevent estimation bias in the right tail, we excluded individuals in the top 5th percentile of pack-years. The best fitting spline regression models for pack-years smoked included knots at the 40th, 60th, and 80th percentiles, corresponding to 13.75, 23, and 40 pack-years for AML, and 20th, 40th, and 60th percentiles, corresponding to 4,12, and 22.2 pack-years for CML For time since quitting, final models included knots at the 40th, 60th, and 80th percentiles, corresponding to approximately 17.5, 26.5, and 37 years for AML, and 18, 27, and 37 years for CML Adjusted ORs (95% CIs) were calculated for specific values of pack-years (10, 20, 30, and 40) compared to never smokers [13]. For time since quitting, the estimates were calculated for 15, 25, 35, and 45 years prior to cancer diagnosis in cases or corresponding reference age in controls [14]. Sixteen subjects were excluded (7 cases and 9 controls) due to missing information on smoking status (current, former, never), leaving 599 cases and 692 controls.

3. Results

Compared with controls, both AML and CML cases were significantly more likely to be male and to have reported radiation therapy for a prior cancer (Table 1). Cases were also more likely obese and to have been exposed to benzene/other solvents. Controls were significantly more likely than cases to be moderate drinkers but with no evidence of a dose response (p > 0.05). Among females, 51% of cases and 43% of controls reported a history of cigarette smoking (p = 0.05); among males 54% of cases and 60% of controls reported a history of cigarette smoking (p = 0.11). The distribution of AML cases by the 2001 WHO subtype classification is presented in Table 2.

Compared to never smokers, ever smokers (OR= 1.38, 95%CI 1.07–1.77), and current smokers (OR=1.53, 95%CI 1.08–2.16), were at increased risk of AML (Table 3), which was further elevated for both former and current smokers who reported smoking ≥1 pack per day. Although less precise, a similar pattern was observed for CML; former and current heavy (≥1 pack/day) smokers had a 1.4-fold (95%CI 0.90–2.30) and 1.6-fold (95%CI 0.84–2.98) increased risk, respectively. Individuals who smoked for >20 years had an increased risk of both AML and CML, regardless of smoking intensity. Furthermore, heavy smokers who smoked ≤20 years had a similar risk to light smokers who smoked >20 years, for both subtypes.

Table 3.

Risk of adult myeloid leukemia, stratified on leukemia type and sex.

| Controls N (%) | AML (413) |

CML (184) |

Men (686) |

Women (600) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases N (%) | OR (95% CI)a | Cases N (%) | OR (95% CI)a | Controls N (%) | Cases N (%) | OR (95% CI)b | Controls N (%) | Cases N (%) | OR(95% CI)b | ||

| Smoking status | |||||||||||

| Never smokedc | 356 (52) | 178 (43) | Reference | 81 (44) | Reference | 155 (46) | 139 (40) | Reference | 201 (57) | 120 (49) | Reference |

| Ever smoked | 333 (48) | 235 (57) | 1.38 (1.07,1.77) | 103 (56) | 1.37 (0.98,1.91) | 181 (54) | 211 (60) | 1.32 (0.97,1.80) | 152 (43) | 127 (51) | 1.42 (1.02,1.98) |

| Former smoker | 223 (32) | 154 (37) | 1.30 (0.98,1.73) | 70 (38) | 1.40 (0.96,2.05) | 126 (38) | 146 (42) | 1.26 (0.89,1.78) | 97 (27) | 78 (32) | 1.38 (0.94,2.03) |

| Current smoker | 110 (16) | 81 (20) | 1.53 (1.08,2.16) | 33 (18) | 1.31 (0.82,2.09) | 55 (16) | 65 (18) | 1.45 (0.94,2.24) | 55 (16) | 49 (20) | 1.49 (0.95,2.34) |

| Former smoker | |||||||||||

| <1 pack/day | 107 (16) | 60 (15) | 1.14 (0.79,1.65) | 32 (17) | 1.42 (0.89,2.28) | 44 (13) | 45 (13) | 1.20 (0.74,1.95) | 63 (18) | 47 (19) | 1.28 (0.82,2.01) |

| ≥1 pack/day | 112 (16) | 91 (22) | 1.45 (1.02,2.06) | 38 (21) | 1.44 (0.90,2.30) | 80 (24) | 98 (28) | 1.28 (0.86,1.89) | 32 (9) | 31 (13) | 1.65 (0.95,2.88) |

| Current smoker | |||||||||||

| <1 pack/day | 68 (10) | 36 (9) | 1.14 (0.73,1.79) | 17 (9) | 1.13 (0.62,2.05) | 30 (9) | 27 (8) | 1.16 (0.65,2.07) | 38 (11) | 26 (11) | 1.14 (0.66,1.99) |

| ≥1 pack/day | 42 (6) | 44 (11) | 2.06 (1.29,3.28) | 16 (9) | 1.58 (0.84,2.98) | 25 (7) | 38 (11) | 1.79 (1.02,3.14) | 17 (5) | 22 (9) | 2.17 (1.10,4.26) |

| Pack years | |||||||||||

| 0 | 358 (52) | 179 (44) | Reference | 81 (44) | Reference | 156 (46) | 152 (40) | Reference | 202 (58) | 136 (50) | Reference |

| >0–15 | 162 (24) | 80 (20) | 0.99 (0.72,1.38) | 45 (24) | 1.24 (0.82,1.87) | 78 (23) | 71 (19) | 0.98 (0.66,1.46) | 84 (24) | 66 (24) | 1.13 (0.76,1.68) |

| >15–30 | 74 (11) | 70 (17) | 1.87 (1.28,2.74) | 26 (14) | 1.54 (0.92,2.58) | 41 (12) | 66 (17) | 1.58 (1.00,2.50) | 33 (9) | 38 (14) | 1.77 (1.05,2.97) |

| >30 | 92 (13) | 76 (19) | 1.59 (1.10,2.31) | 33 (18) | 1.59 (0.97,2.60) | 61 (18) | 89 (24) | 1.43 (0.95,2.15) | 31 (9) | 34 (12) | 1.68 (0.97,2.91) |

| Smoked ≤ 20 years | 147 (21) | 78 (19) | 1.03 (0.74,1.44) | 43 (23) | 1.23 (0.81,1.88) | 80 (24) | 79 (21) | 1.04 (0.71,1.50) | 67 (19) | 52 (19) | 1.10 (0.71,1.68) |

| <1 pack/day | 95 (14) | 39 (10) | 0.83 (0.54,1.26) | 23 (13) | 1.04 (0.62,1.75) | 41 (12) | 28 (8) | 0.81 (0.47,1.40) | 54 (15) | 34 (14) | 1.00 (0.61,1.64) |

| >1 pack/day | 50 (7) | 39 (10) | 1.43 (0.90,2.28) | 20 (11) | 1.61 (0.89,2.90) | 38 (11) | 47 (14) | 1.38 (0.84,2.25) | 12 (3) | 12 (5) | 1.55 (0.66,3.61) |

| Smoked>20 years | 183 (27) | 151 (37) | 1.64 (1.23,2.20) | 61 (33) | 1.53 (1.03,2.27) | 101 (30) | 150 (39) | 1.48 (1.05,2.10) | 82 (23) | 87 (32) | 1.63 (1.12,2.40) |

| <1 pack/day | 79 (12) | 55 (14) | 1.51 (1.02,2.25) | 26 (14) | 1.69 (1.01,2.85) | 33 (10) | 42 (12) | 1.59 (0.94,2.68) | 46 (13) | 39 (16) | 1.56 (0.95,2.56) |

| ≥1 pack/day | 103 (15) | 93 (23) | 1.72 (1.21,2.43) | 34 (18) | 1.45 (0.90,2.34) | 67 (20) | 88 (26) | 1.44 (0.96,2.16) | 36 (10) | 39 (16) | 1.91 (1.14,3.20) |

| Cessation of smoking | |||||||||||

| Current Smoker | 110 (16) | 81 (20) | Reference | 33 (18) | Reference | 55 (16) | 65 (19) | Reference | 55 (16) | 49 (20) | Reference |

| Quit <15 years | 64 (9) | 55 (13) | 1.04 (0.65,1.67) | 27 (15) | 1.33 (0.72,2.43) | 34 (10) | 50 (14) | 1.05 (0.59,1.88) | 30 (9) | 32 (13) | 1.15 (0.61,2.16) |

| Quit 15–29 years | 72 (11) | 51 (12) | 0.83 (0.51,1.35) | 25 (14) | 1.14 (0.61,2.13) | 40 (12) | 49 (14) | 0.87 (0.48,1.55) | 32 (9) | 27 (11) | 0.94 (0.49,1.82) |

| Quit ≥30 years | 83 (12) | 44 (11) | 0.64 (0.39,1.06) | 18 (10) | 0.77 (0.39,1.52) | 50 (15) | 43 (12) | 0.64 (0.35,1.16) | 33 (9) | 19 (8) | 0.71 (0.35,1.44) |

| Never smoker | 356 (52) | 178 (44) | 0.65 (0.46,0.92) p, trend =0.05 |

81 (44) | 0.76 (0.48,1.21) p, trend=0.31 |

155 (46) | 139 (40) | 0.68 (0.44,1.06) p, trend =0.28 |

201 (57) | 120 (49) | 0.67 (0.43,1.05) p, trend= 0.07 |

Adjusted for age (continuous), sex, and BMI (under/normal weight, overweight, obese).

Adjusted for age (continuous) and BMI (under/normal weight, overweight, obese).

Referent group is “never smoked” for all Smoking Status models.

There was no evidence for effect modification of smoking and myeloid leukemia, AML, or CML, by age (<60 vs. ≥60; data not shown) or sex (Table 3); however, given the paucity of data for women (i.e., small sample size or lower prevalence of smoking in earlier studies), data are presented stratified on sex in order to provide stable estimates for females. Female ever smokers had a 42% significant increased risk overall, which was similar for AML (OR=1.39, 95%CI = 0.96–2.02) and CML (OR=1.53, 95%CI 0.93–2.52), and primarily due to current heavy smokers (2-fold risk or higher for myeloid cases combined, AML, and CML). Similarly, there was a 32% increased risk of myeloid leukemia among male ever smokers, which was similar for AML and CML, and primarily confined to heavy smokers.

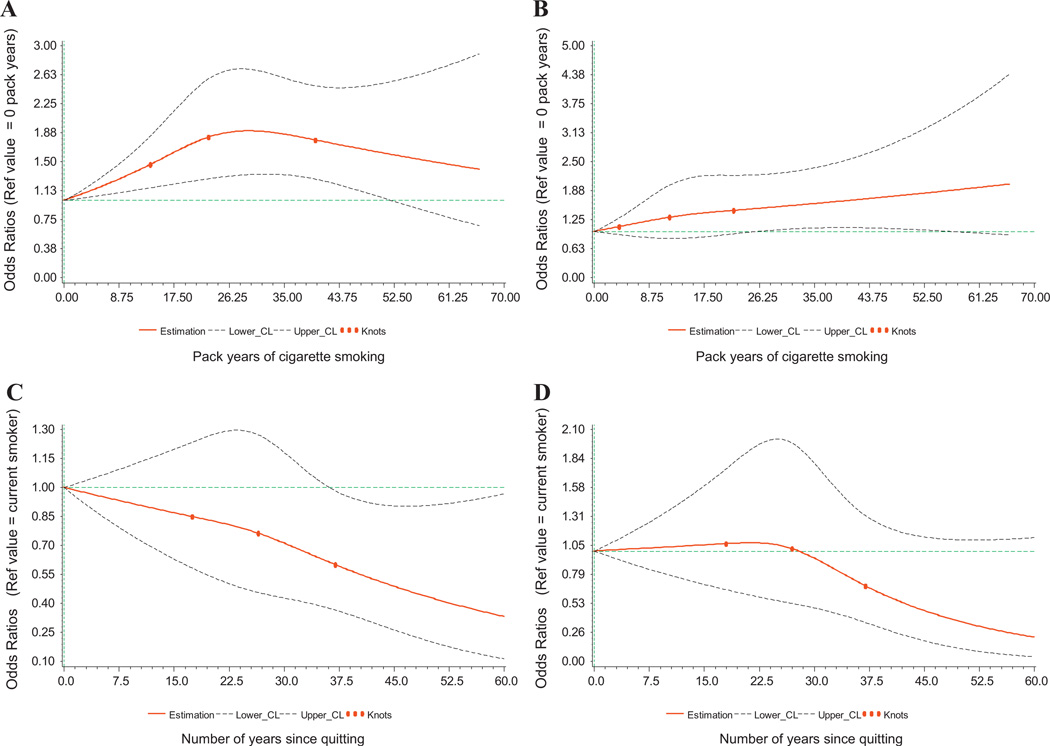

The dose-response evaluation using restricted cubic spline regression revealed a highly significant association between smoking pack-years and risk of AML (p = 0.001) and a significant non-linear association (p = 0.04) (Fig. 1). Risk of AML increased with increasing pack-years until ∼30 years, and then gradually declined (Fig. 1a). Estimated ORs for 20,30, and 40 pack-years were 1.72 (1.25–2.37), 1.90 (1.34–2.69), and 1.78 (1.28–2.48), respectively. The spline curves were similar for men and women, except risks were slightly higher for women beyond 20 pack-years (data not shown). In contrast, there was a monotonic increase in CML risk with increasing pack-years of smoking (poverall = 0.06; pnon-linear = 0.57; Fig. 1b); estimated ORs for 20, 30, and 40 pack-years were 1.43 (0.92–2.21), 1.54 (1.04–2.27), and 1.66 (1.08–2.54), respectively. Beyond 25 pack-years, the rate of increase of CML was steeper for women than for men (ORs for 30, 40, and 50 pack-years = 1.42, 1.48. 1.54 for men vs. 1.79, 2.49, 3.47 for women; data not shown).

Fig. 1.

A–D. Estimates of OR (solid lines) and 95% CI (dotted lines) of smoking pack-years and AML (A) and CML (B) risk, and smoking cessation (years since quitting) and AML (C) and CML (D) risk, using a restricted cubic spline regression model adjusted for age, sex, and BMI. Knot locations are marked by filled circles. Never smokers are the reference group for the model of smoking pack-years. Current smokers have aquit-time of zero and are the reference group for the model of smoking cessation; never smokers are excluded. The horizontal line represents a null association (OR = 1.00).

Risk estimates are also presented by AML WHO subtype categories (Table 4). Significantly increased risk (3.5-fold and higher) was associated with AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities among former heavy smokers, and AML with multilineage dysplasia and AML with a specific differentiation pattern among current heavy smokers. Further evaluation by individual WHO subtype revealed a borderline significant or significantly increased risk for AML with abnormalities involving inv(16)(p13q22) or t(16;16)(p13;q22) and acute promyelocytic leukemia among former smokers, and AML with t(8;21)(q22;q22), AML with multilineage dysplasia, AML with maturation, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and acute monoblastic and monocytic leukemia among current smokers (ORs 2.3–4.0).

Table 4.

Cigarette smoking and risk of AML, stratified on WHO subtype categoriesa

| AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities |

AML with multilineage dysplasia |

AML without a specific lineage of differentiation |

AML with a specific differentiation pattern |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca/Co | OR | 95% CI | Ca/Co | OR | 95% CI | Ca/Co | OR | 95% CI | Ca/Co | OR | 95% CI | |

| Never smokedb | 41/356 | 1.00 | Reference | 18/356 | 1.00 | Reference | 69/356 | 1.00 | Reference | 37/356 | 1.00 | Reference |

| Ever smoked | 50/333 | 1.61 | 1.01–2.55 | 22/333 | 1.08 | 0.56–2.09 | 91/333 | 1.32 | 0.92–1.88 | 52/333 | 1.38 | 0.87–2/18 |

| Former smoker | 37/223 | 2.34 | 1.37–3.97 | 13/223 | 0.76 | 0.36–1.63 | 62/223 | 1.22 | 0.82–1.82 | 29/223 | 0.98 | 0.57–1.67 |

| Current smoker | 13/110 | 0.87 | 0.44–1.73 | 9/110 | 2.30 | 0.96–5.52 | 29/110 | 1.52 | 0.93–2.51 | 23/110 | 2.45 | 1.36–4.42 |

| Former smoker | ||||||||||||

| <1 pack/day | 14/107 | 1.65 | 0.83–3.28 | 4/107 | 0.60 | 0.19–1.83 | 29/107 | 1.29 | 0.79–2.12 | 6/107 | 0.49 | 0.20–1.21 |

| ≥ 1 pack/day | 23/112 | 3.57 | 1.86–6.85 | 9/112 | 0.91 | 0.38–2.17 | 32/112 | 1.14 | 0.69–1.87 | 21/112 | 1.28 | 0.69–2.35 |

| Current smoker | ||||||||||||

| <1 pack/dayc | 2/68 | – | – | 2/68 | – | – | 17/68 | 1.54 | 0.84–2.83 | 9/68 | 1.72 | 0.77–3.82 |

| ≥ 1 pack/day | 11/42 | 2.07 | 0.95–4.49 | 7/42 | 4.44 | 1.65–11.9 | 11/42 | 1.39 | 0.67–2.87 | 14/42 | 3.53 | 1.71–7.26 |

Models adjusted for age (continuous), BMI (underweight/normal, overweight, obese), and sex.

Referent group is “never smoked” for all models.

Estimates not provided for fewer than 4 cases.

With regard to smoking cessation, among long-term quitters (≥30 years), risk of AML and CML was comparable to non-smokers, and was also observed for all myeloid leukemia cases combined for both men and women, separately (Table 3). There was a borderline significant (p = 0.07) monotonic decrease in risk of AML with increasing time since quitting (Fig. 1C). Compared with current smokers, the ORs (95%CI) for former smokers who quit 15, 25, 35, and 45 years prior to enrollment were 0.87 (0.63–1.20), 0.78 (0.47–1.29), 0.63 (0.39–1.03), and 0.49 (0.26–0.91)(data not shown). For CML, diminished risk for former smokers occurred much later, >30 years since quitting smoking (p = 0.19) (Fig. 1D). The ORs for quitting 15, 25, 35, and 45 years prior to enrollment were 1.05 (0.70–1.59), 1.05 (0.55–2.02), 0.75 (0.40–1.43), and 0.46 (0.19–1.13), respectively.

4. Discussion

Our large population-based case-control study provided evidence that smoking is associated with an increased risk of both AML and CML in both men and women. AML risk increased sharply with increasing pack-years of smoking and then plateaued around 30 pack-years, and decreased monotonically with increasing years since smoking cessation. CML risk increased gradually with increasing pack-years and decreased only after 30 years since smoking cessation.

Most studies have either not reported results separately for women or lacked precision in their estimates, likely due to small sample size or low prevalence of smoking. A non-significant increased risk of AML was recently reported in ever smokers in a large female cohort (RR = 1.10, 95%CI 0.96–1.26), but data on AML subtypes or CML were not provided, nor was smoking extensively modeled [14]. We observed a significantly increased risk of myeloid leukemia among women, which was strongest in current or long-term (>20 years) heavy smokers. The elevated risk in women was apparent for both AML and CML.

Similarly, a precise characterization of the association between smoking and CML is lacking. In smaller CML studies (<100 cases), no significant association with ever smoking was observed [15–17], nor did comparable sized studies (169 and 255 cases) observe an association for ever smokers (OR = 0.81, 95%CI 0.53–1.2) [18], current smokers (OR = 0.7, 95%CI = 0.4–1.1) [19] or pack-years of smoking (which was substantially lower [19] or not provided [18]). While evidence is stronger for AML, an association with CML cannot be ruled out if the detectable level of risk is present only for higher smoking intensity and/or duration. Pooled studies are needed to examine CML risk according to smoking intensity and duration, particularly for women.

Many studies have reported a dose-response effect for smoking intensity (cigarettes/day) [20–23], duration (total years smoked) [24,25], or a combination (pack-years) [26,27] from parametric analyses, typically by evaluating tests for trend across categories or as a continuous variable, which assumes a linear relation. Few leukemia studies have used non-parametric methods. An analysis using fractional polynomials revealed a gradually increasing AML risk with increasing smoking pack-years, with significant risk not becoming apparent until >35 pack-years [28]. Our evaluation using cubic spline regression revealed a non-linear association with AML, whereby the risk sharply increased for the first twenty pack-years and then plateaued. Survivor bias or competing risks of smoking and other chronic diseases, and/or other malignancies could account for this observation; alternatively, plateauing could indicate a biological threshold of risk.

Given the heterogeneity of AML and the prognostic significance of different subtypes, it is reasonable to hypothesize that etiology may also vary. While numerous investigations have evaluated the association between smoking and individual AML chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., −5/5q-, −7/7q-, +8) [26,28–31], few have reported results using the relatively recent WHO classification, which incorporates clinical, morphologic, immunophenotypic, and genetic features [12]. In a large hospital-based case-control study in Shanghai, smoking (ever vs. never) was associated with a 30% increased risk of AML (95%CI 1.0–1.6), but in contrast to our study, no association was observed with recurrent genetic abnormalities (OR=1.10, 95%CI 0.71–1.71). However, a borderline significant increased risk was observed for AML with multilineage dysplasia (OR= 1.45, 95%CI 0.92–2.30) and AML not otherwise categorized (OR= 1.48 95%CI 0.96–2.26) [25]. Given the large number of AML WHO subtypes, pooled studies are needed to further clarify associations.

Smoking cessation has also been previously associated with a decreased risk of acute myeloid leukemia in adults [17,27,28,32,33]. Similar to our findings, other studies have reported no increased risk of AML among long-term quitters, although the associated number of years since quitting has varied among studies, from 15 to 18 years [19,29,32].

Our results allowed for comparison with previous studies and for addressing research gaps. Nevertheless, limitations should be considered. No statistical adjustment was made for multiple comparisons, thus some results may be due to chance. There is potential for recall bias since cigarette smoking was based on self-report. However, the prevalence of current cigarette smoking among our controls was similar to population estimates in Minnesota (men: 18.6%, women: 14.9%) [34]. Furthermore, unlike many other studies of rapidly fatal diseases, we utilized rapid case ascertainment and did not rely on proxy interviews, which are more prone to misclassification and bias [35]. While rapid ascertainment improved rates of case enrollment, 230 out of 1178 pathologically confirmed cases were not referred due to death soon after diagnosis. It is possible that these cases might represent some of the heaviest smokers, which would result in an even stronger true association between smoking and leukemia than the one we observed. Our questionnaire did not consider changes in smoking intensity (cigarettes/day) or gaps in smoking (multiple start/stop dates), thus smoking intensity or duration may be overestimated in some individuals. As the smoking-myeloid leukemia association is not well known among the public, misclassification would likely be non-differential among cases and controls [36].

In conclusion, our analyses contribute further evidence that smoking is associated with an increased risk of AML and CML in both men and women. Importantly, we also show that smoking cessation leads to an attenuation of leukemia risk, such that in long-term quitters risk is comparable to never smokers. These results emphasize the importance of including leukemia in public health messaging of cancer risk associated with cigarette smoking.

Acknowledgments

Role of the funding source

NIH T32 CA099936, R25 CA047888, R01 CA107143, and K05 CA157439.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no financial disclosures to report.

Contributor Information

Jessica R.B. Musselman, Email: bruce087@umn.edu.

Cindy K. Blair, Email: blairc@uab.edu.

James R. Cerhan, Email: Cerhan.James@mayo.edu.

Phuong Nguyen, Email: Nguyen.Phuong@mayo.edu.

Betsy Hirsch, Email: hirsc003@umn.edu.

Julie A. Ross, Email: rossx014@umn.edu.

References

- 1.Vardiman JW. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: an overview with emphasis on the myeloid neoplasms. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;184(1–2):16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/, based on November 2011 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deschler B, Lubbert M. Acute myeloid leukemia: epidemiology and etiology. Cancer. 2006;107(9):2099–2107. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF., Jr . Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross ME, Mahfouz R, Onciu M, Liu HC, Zhou X, Song G, et al. Gene expression profiling of pediatric acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2004;104(12):3679–3687. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownson RC, Novotny TE, Perry MCCigarette smoking, adult leukemia. A meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(4):469–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vineis P, Alavanja P, Buffler P, Fontham E, Franceschi S, Gao YT, et al. Tobacco and cancer: recent epidemiological evidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(2):99–106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson KJ, Blair CM, Fink JM, Cerhan JR, Roesler MA, Hirsch BA, et al. Medical conditions and risk of adult myeloid leukemia. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(7):1083–1089. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9977-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross JA, Blair CK, Cerhan JR, Soler JT, Hirsch BA, Roesler MA, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug and acetaminophen use and risk of adult myeloid leukemia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(8):1741–1750. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slattery ML, Edwards SL, Caan BJ, Kerber RA, Potter JD. Response rates among control subjects in case-control studies. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5(3):245–249. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bacher U, Kern W, Schnittger S, Hiddemann W, Schoch C, Haferlach T. Further correlations of morphology according to FAB and WHO classification to cytogenetics in de novo acute myeloid leukemia: a study on 2235 patients. Ann Hematol. 2005;84(12):785–791. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-1099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2002;100(7):2292–2302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose–response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med. 2010;29(9):1037–1057. doi: 10.1002/sim.3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroll ME, Murphy F, Pirie K, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V. Alcohol drinking, tobacco smoking and subtypes of haematological malignancy in the UK Million Women Study. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(5):879–887. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernberg P, Odenbro A, Bellocco R, Boffetta P, Pawitan Y, Zendehdel K, et al. Tobacco use, body mass index, and the risk of leukemia and multiple myeloma: a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Cancer Res. 2007;67(12):5983–5986. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman GD. Cigarette smoking, leukemia, and multiple myeloma. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3(4):425–428. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90071-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson DB, Terschuren C, Pohlabeln H, Jockel KH, Hoffmann W. Temporal patterns of association between cigarette smoking and leukemia risk. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(1):43–50. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bjork J, Albin M, Welinder H, Tinnerberg H, Mauritzson N, Kauppinen T, et al. Are occupational, hobby, or lifestyle exposures associated with Philadelphia chromosome positive chronic myeloid leukaemia? Occup Environ Med. 2001;58(11):722–727. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.11.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasim K, Levallois P, Abdous B, Auger P, Johnson KC. Lifestyle factors and the risk of adult leukemia in Canada. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16(5):489–500. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-7115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brownson RC, Chang JC, Davis JR. Cigarette smoking and risk of adult leukemia. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134(9):938–941. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garfinkel L, Boffetta P. Association between smoking and leukemia in two American Cancer Society prospective studies. Cancer. 1990;65(10):2356–2360. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900515)65:10<2356::aid-cncr2820651033>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinlen LJ, Rogot E. Leukaemia and smoking habits among United States veterans. Br Med J. 1988;297(6649):657–659. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6649.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLaughlin JK, Hrubec Z, Linet MS, Heineman EF, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF., Jr Cigarette smoking and leukemia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(16):1262–1263. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.16.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Severson RK. Cigarette smoking and leukemia. Cancer. 1987;60(2):141–144. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870715)60:2<141::aid-cncr2820600202>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong O, Harris F, Yiying W, Hua F. A hospital-based case-control study of acute myeloid leukemia in Shanghai: analysis of personal characteristics, lifestyle and environmental risk factors by subtypes of the WHO classification. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2009;55(3):340–352. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandler DP, Shore DL, Anderson JR, Davey FR, Arthur D, Mayer RJ, et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of acute leukemia: associations with morphology and cytogenetic abnormalities in bone marrow. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(24):1994–2003. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.24.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Severson RK, Davis S, Heuser L, Daling JR, Thomas DB. Cigarette smoking and acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(3):418–422. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bjork J, Albin M, Mauritzson N, Stromberg U, Johansson B, Hagmar L. Smoking and acute myeloid leukemia: associations with morphology and karyotypic patterns and evaluation of dose-response relations. Leuk Res. 2001;25(10):865–872. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bjork J, Johansson B, Broberg K, Albin M. Smoking as a risk factor for myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia and its relation to cytogenetic findings: a case-control study. Leuk Res. 2009;33(6):788–791. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crane MM, Strom SS, Halabi S, Berman EL, Fueger JJ, Spitz MR, et al. Correlation between selected environmental exposures and karyotype in acute myelocytic leukemia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5(8):639–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moorman AV, Roman E, Cartwright RA, Morgan GJ. Smoking and the risk of acute myeloid leukaemia in cytogenetic subgroups. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(1):60–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kane EV, Roman E, Cartwright R, Parker J, Morgan G. Tobacco and the risk of acute leukaemia in adults. Br J Cancer. 1999;81(7):1228–1233. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richardson DB, Terschu¨ren C, Pohlabeln H, Jöckel K-H, Hoffmann W. Temporal patterns of association between cigarette smoking and leukemia risk. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.State-specific prevalence of cigarette smoking and smokeless tobacco use among adults - United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(43):1400–1406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker AM, Velema JP, Robins JM. Analysis of case control data derived in part from proxy respondents. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127(5):905–914. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rock V, Malarcher A, Kahende J, Asman K, Husten C, Caraballo R. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(44):1157–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]