Nasal mucosal epithelial cells form the first line of defense by maintaining a barrier to restrict potentially harmful airborne substances and pathogens. To aid in host defense, specialized epithelial cells in submucosal glands as well as on the mucosal surface secrete mucous that helps to immobilize pathogens and other harmful substances. Beneath this mucous blanket resides an aqueous surface liquid layer, which allows proper ciliary function to clear mucous and entrapped pathogens. In concert with maintenance of a physical barrier, airway epithelium secretes dozens of antimicrobial peptides and proteins that become incorporated into the mucous and aqueous lining fluids1, 2. It has become clear that proper functioning of the epithelium is essential for suppressing the growth of pathogenic organisms and promoting healthy upper airway physiology. Dysfunction in innate immune expression of host defense molecules has been linked to many airway diseases3-8. Surprisingly, the regional distribution of important epithelial derived antimicrobial proteins secreted into upper airways has not been studied in detail. In this study, we analyzed the expression of select antimicrobial proteins that are known to be secreted into the lining fluids of the upper airways in two different anatomical sites of the sinonasal mucosa in healthy human subjects, namely the inferior region (inferior turbinate - IT), and the superior region (uncinate tissue - UT). We chose IT, as it is the proximal point of contact of inhaled air containing particulate matter and potential pathogens. Moreover, studies of CRS and other diseases of the upper airways routinely use IT tissue as a control tissue to make comparisons with nasal polyps. UT was chosen for its important role in the drainage pathways of maxillary, frontal and anterior ethmoid sinuses. We chose to study the expression of S100A7 (S100 family), hBD2 (β-Defensin family), SPLUNC1 (PLUNC family), and lactoferrin, as they represent broad families of antimicrobial proteins, which are either constitutively present or induced by inflammation triggered by pathogens and collectively have antimicrobial effects against a variety of pathogens (bacteria, fungi and viruses).

Sinonasal tissue samples from IT and UT were collected from subjects undergoing surgery to correct non-inflammatory conditions, including facial anatomical defects (deformity, trauma etc.), to improve airflow and during the course of skull base surgery to remove tumors. The subjects were not diagnosed with any upper or lower airway diseases at the time of sample collection. Detailed patient characteristics are provided in table EI. The Investigational Review Board of Northwestern University approved all methods for the present study, and all patients provided informed consent. At the time of surgery, tissues and nasal epithelial scraping cells were collected and stored for further analysis. Tissue samples and epithelial cells were analyzed for mRNA expression by real time PCR. Protein expression and localization were analyzed using ELISA and immunohistochemistry, respectively. AB/PAS staining was performed to characterize the glandular differences between IT and UT. Details of the methods used can be found in the online repository and our other publications5, 7.

Regional variation in expression of innate host defense molecules

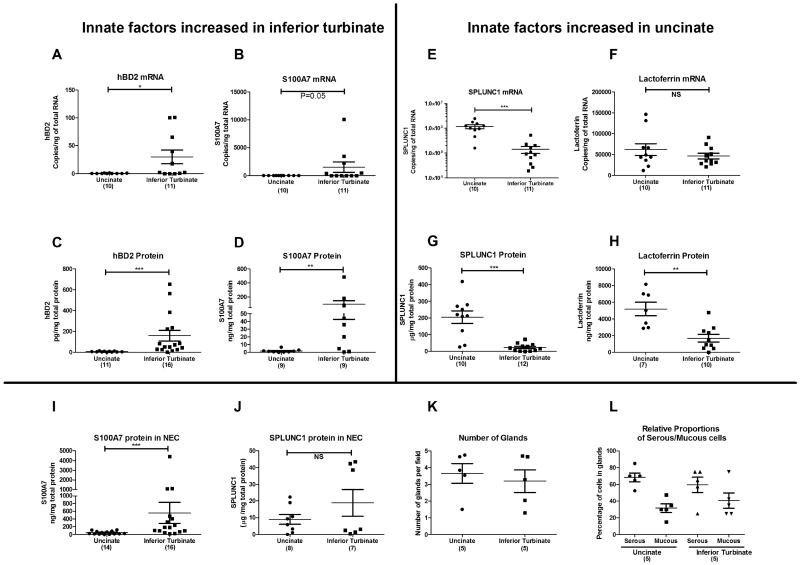

Earlier studies of S100A7 expression in chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) by our group indicated that S100A7 was differentially expressed in IT and UT tissues7. To determine regional variations in mRNA expression of this and other innate immune molecules in sinonasal tissues, we performed real-time PCR in a total of 21 samples (10 UT and 11 IT). We found that the mRNA expression of S100A7 and hBD2 was considerably higher in IT tissue compared to that of UT (400 and 80 fold, respectively, Figure 1, A and B). In stark contrast, UT had a substantially higher mRNA expression of SPLUNC1 compared to IT tissue (8 fold, Figure 1E – note log scale). Lactoferrin mRNA expression did not differ between UT and IT (Figure 1F). Next, we attempted to confirm the mRNA findings at the protein level using ELISA. In concordance with our mRNA data, the expression of S100A7 and hBD2 proteins was significantly higher in IT than UT, by 40 and 21 fold, respectively (p<0.05) (Figure 1, C and D). Likewise, SPLUNC1 protein was elevated in UT when compared to IT (8 fold, p<0.05) (Figure 1G). In contrast to the mRNA data, lactoferrin protein was three fold higher in UT than in IT (Figure 1H). Since it is well known that sinuses contribute a majority of the respiratory NO production, and since NO plays an antimicrobial role, we also evaluated the expression of various nitric oxide synthases (NOS1, NOS2 and NOS3) in IT and UT (Figure E1). We confirmed the previous studies by Lundberg et al.9, showing that expression of mRNA for NOS2, the major form of NOS in the sinuses involved in production of NO, was much higher in UT compared to IT (22 fold, 292.3±82.8 vs. 13.3±9.4 copies/ng total RNA, p=0.0006, n=7-8). Interestingly, we observed that NOS1 (4.7 fold) and NOS3 (1.6 fold) were elevated in the IT compared to UT. Taken together, these observations indicate that there is a differential expression of molecules involved in innate host defense in sinonasal tissues taken from different anatomical sites of healthy human subjects.

Figure 1. Evaluation of expression of antimicrobial mRNA and protein in uncinate and inferior turbinates of healthy human subjects.

Total RNA and protein was extracted from uncinate and inferior turbinate tissues of healthy subjects. Expression of mRNA was analyzed by real-time PCR. Expression of proteins was analyzed by ELISA. AB/PAS staining was used to observe differences in the presence of glands. Data for panel D (Tieu et al.) and E-H (UT only-Seshadri et al.) are taken from earlier publications as indicated. NS- not significant, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 (Mann-Whitney U test)

Immunohistochemical analysis of S100A7 and SPLUNC1

We confirmed our previous observation that S100A7 was primarily expressed in the mucosal epithelium with modest staining in submucosal glands, whereas SPLUNC1 was highly expressed in the submucosal glands with minimal presence in the mucosal epithelium (Figure E2)5, 7. To further confirm the IHC data indicating high expression levels of S100A7 in the surface epithelium, we performed ELISA with isolated nasal epithelial cells from IT and UT tissues. In agreement with our ELISA data in whole tissue homogenates, we found that IT epithelial cells had a 12 fold higher S100A7 protein expression compared to UT epithelial cells (Figure 1I). In contrast, the expression of SPLUNC1 in epithelial cells from IT and UT was not different (Figure 1J). This suggests that the regional variation of SPLUNC1 expression in tissue samples may be caused by variability in expression in glands rather than in mucosal epithelium (see below). These findings also suggest that the underlying molecular mechanism responsible for the regional variation of S100A7 may differ from the differential transcriptional expression mechanism of SPLUNC1.

Submucosal gland density and proportions of serous and mucous cells are similar in IT and UT

To further understand the regional variations between IT and UT tissue in the expression of host defense molecules that are largely derived from submucosal glands, specifically SPLUNC1 and lactoferrin, we assessed relative expression of these molecules in both serous and mucous cells within glands from both locations. In initial studies, we stained both tissues with mucous (AB) and serous (PAS) stains. We failed to observe any appreciable differences in the number or proportion of serous and mucous cells in IT when compared to UT tissues (Figure 1, K and L and Figure E3). These experiments indicate that the regional variation of host defense molecules is not explained by regional variation in either submucosal gland density or proportions of serous and mucous cells within glands. We must caution that while there is no appreciable difference in the number of glands based on microscopic observation, it remains possible that there are differences in the volume of glands between inferior turbinate and uncinate tissues.

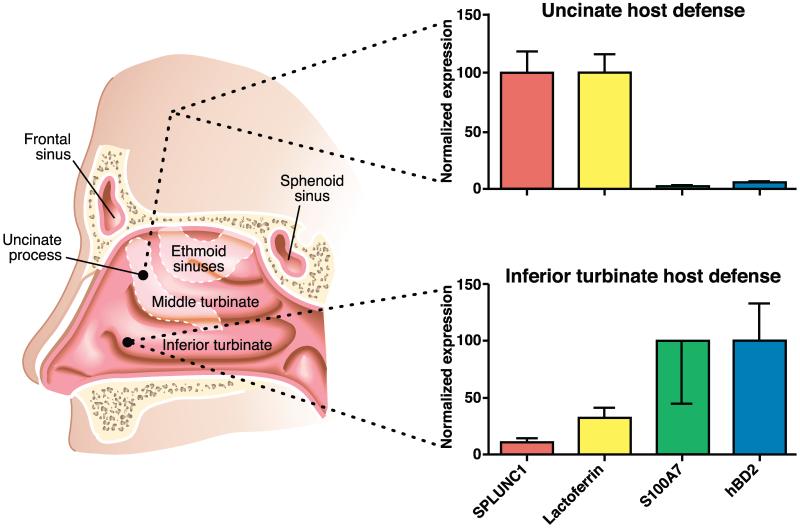

A pictorial summary of our findings is shown in Figure 2. Our finding of differential expression of innate immune proteins between IT and UT is unexpected, as these tissues have been used interchangeably to study gene expression levels and as control tissue to make comparisons with diseased tissues such as nasal polyps in the case of CRS. A recent report from Laudien et al. compared the expression of host defense molecules between the nasal vestibule (anterior part of the nasal cavity) and the IT region of the proper nasal mucosa10. The findings of differential expression of some of the molecules tested in their study between nasal vestibule and IT are interesting, though not surprising, as it is known that epithelial cells of the nasal vestibule are similar to keratinocytes (stratified squamous), which are very different from respiratory epithelial cells (pseudostratified columnar).

Figure 2. Regional differences in the expression of innate host defense molecules in sinonasal mucosa.

This study demonstrates that the expression of some innate host defense molecules in various regional tissues is quite variable, with expression of some glandular proteins (lactoferrin and SPLUNC1) greater in UT compared to IT. Interestingly, we initially used the mucin MUC5B as a marker of mucous cells, but found a differential expression similar to that of SPLUNC1 – i.e. high levels in UT and much lower levels in IT (6181±1993 vs 2147±411 copies /ng of total RNA, p= 0.03). This supports the concept that submucosal glands near the UT are a much richer source of a number of host defense molecules than corresponding glands in the IT region. The apparent differences that we observe could be due to the different embryonic origins of these tissues (maxilloturbinal (IT) Vs ethmoturbinal (UT)). As a result of different embryonic origins, these tissues could be governed by ontologically different gene regulation pathways. Alternatively, regionally dependent environmental exposures may also be a cause or factor in the differential expression observed. Finally, as UT tissue is located at a point of drainage of various sinuses, it is tempting to speculate that increased expression of host defense molecules such as SPLUNC1, lactoferrin and MUC5B in UT may be important for additional host defense in sinus drainage pathways. In support of this hypothesis, there is emerging evidence indicating that SPLUNC1 has surfactant properties and may be involved in biophysical aspects of mucociliary clearance11. Our data also suggest that there may potentially be different microbiota and/or susceptibilities for microbial colonization in the proximal (IT) and distal (UT) areas of the sinonasal mucosa, with UT having a more profound expression of submucosal gland derived antimicrobial proteins.

In conclusion, our findings indicate anatomic site-specific expression of antimicrobial proteins in sinonasal tissues, suggesting the possibility of specialized regional functions of these proteins within the sinonasal cavity. Also, our findings of different intrinsic baseline levels of gene expression in IT and UT suggest a careful selection of the site of control tissue is needed when studying host defense molecules.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported in part by NIH grants RO1 HL 078860, R37 GK068546 and RO1 AI072570 and by the Ernest S. Bazley Trust.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kato A, Schleimer RP. Beyond inflammation: airway epithelial cells are at the interface of innate and adaptive immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:711–20. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ooi EH, Wormald PJ, Tan LW. Innate immunity in the paranasal sinuses: a review of nasal host defenses. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:13–9. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baines KJ, Simpson JL, Gibson PG. Innate immune responses are increased in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu HW, Thaikoottathil J, Rino JG, Zhang G, Wu Q, Moss T, et al. Function and regulation of SPLUNC1 protein in Mycoplasma infection and allergic inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;179:3995–4002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seshadri S, Lin DC, Rosati M, Carter RG, Norton JE, Suh L, et al. Reduced expression of antimicrobial PLUNC proteins in nasal polyp tissues of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2012;67:920–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avila PC, Schleimer RP. Allergy and Allergic Diseases. 2 ND ed. Wiley-Blackwell; Hoboken, NJ: 2008. Airway Epithelium. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tieu DD, Peters AT, Carter RG, Suh L, Conley DB, Chandra R, et al. Evidence for diminished levels of epithelial psoriasin and calprotectin in chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:667–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramanathan M, Jr., Lee WK, Spannhake EW, Lane AP. Th2 cytokines associated with chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps down-regulate the antimicrobial immune function of human sinonasal epithelial cells. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:115–21. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundberg JO, Farkas-Szallasi T, Weitzberg E, Rinder J, Lidholm J, Anggaard A, et al. High nitric oxide production in human paranasal sinuses. Nat Med. 1995;1:370–3. doi: 10.1038/nm0495-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laudien M, Dressel S, Harder J, Glaser R. Differential expression pattern of antimicrobial peptides in nasal mucosa and secretion. Rhinology. 2011;49:107–11. doi: 10.4193/Rhino10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGillivary G, Bakaletz LO. The multifunctional host defense peptide SPLUNC1 is critical for homeostasis of the mammalian upper airway. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.