Background

Retreatment tuberculosis (TB) is a TB episode occurring in patients who have received prior TB treatment1. In Cape Town, South Africa, retreatment TB has consistently accounted for 30% of notified TB cases over a seven year period2. Retreatment TB may follow completion, interruption or failure of previous treatment and consequently retreatment TB has been considered a quality measure of TB control programs.

Retreatment TB data are often presented as a proportion of TB cases in a defined period which does not allow linkage of episodes to individuals. However, longitudinal cohort analysis enables linkage of TB episodes and assessment of time periods between episodes.

Retreatment TB is due to either the reactivation of persistent organisms following sub-optimally treated TB, or exogenous re-infection. Molecular technologies have enabled the relative role of re-infection and reactivation to be determined in specific settings3-5. HIV-infection increases the incidence of both re-infection and reactivation disease5;6. While antiretroviral treatment (ART) reduces the risk of TB disease7, there are few data on the impact of HIV and ART on the aetiology of retreatment TB.

In order to elucidate the role of re-infection, reactivation, HIV and ART in retreatment disease in a high HIV and TB prevalent setting, we analyzed retreatment TB cases in a community, over a ten-year period. We linked retreatment episodes of individuals to prior TB treatment outcomes, and stratified analyses by HIV status and ART use. Genotypic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) isolates was used to distinguish between re-infection and reactivation.

Methods

The study took place in a geographically well-demarcated township in Cape Town, with a population of 16,858 and adult HIV prevalence of 23-25%8;9. TB care, provided by a single primary care clinic, followed the South African National TB Control Program guidelines10, based on the WHO-recommended directly observed treatment short course (DOTS) program. We have previously reported high TB notification rates11, substantial TB transmission12 and a wide diversity of circulating Mtb strains in this community13. ART was introduced into this community in 2003 and by 2010 over 30% of the HIV-infected population were receiving treatment14.

All resident adult TB cases (≥15 years of age) diagnosed from 2001 to end 2010 were enrolled in the study, irrespective of sputum smear or culture status. Demographic and clinical data were extracted from the clinic TB register and patient folders.

M.tuberculosis isolates

Sputum specimens obtained from TB suspects were assessed for the presence of Mtb bacilli by fluorescent (auramine) microscopy and auramine-positive sputum samples were cultured on Lowenstein-Jensen (LJ) slants. From 2001 to 2005, culture and drug sensitivity testing (DST) was performed on all retreatment cases, and on new cases if requested by the clinic doctor. From 2006 Mtb culture was performed on all specimens, regardless of smear result, and DST was performed on all culture-positive specimens.

Mtb culture-positive isolates were shipped to the Public Health Research Institute (PHRI) Tuberculosis Center at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ). IS6110-based Restriction Fragment length Polymorphism (RFLP) analysis was performed on each isolate. Mtb isolates with DNA fingerprints with an identical hybridization banding pattern were considered to be the same strain and assigned a strain code following the previously described nomenclature system15. Storage, shipment and analysis of specimens have been described elsewhere16.

The Faculty of Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Cape Town and the Institutional Review Board of the UMDNJ approved the study.

Definitions

A new TB case was defined as a first-time TB diagnosis1, with initiation of treatment. Treatment failure was defined when sputum remained auramine-positive at the end of treatment.

Retreatment TB was any TB diagnosis subsequent to new TB, regardless of the new TB case treatment outcome. “Retreatment pair” referred to two successive TB episodes in the same patient (ie patient with two TB episodes forms one retreatment pair; a patient with three TB episodes forms two retreatment pairs). Retreatment pairs were identified through a series of matching queries performed in Microsoft Access. Matches were made on unique identifiers including health clinic folder number, first name and surname, and combinations thereof. Matches were hand checked, and confirmed on age, gender and address.

Matched and non-matched TB strains were isolates from retreatment pairs with identical and non-identical RFLP patterns respectively. Matched pairs were interpreted as reactivation of the initial TB infection, and non-matched pairs as exogenous re-infection.

An HIV model for the community has previously been developed14, based on biennial censuses, the Actuarial Society of South Africa's 2003 AIDS and Demographic model17 and community HIV surveys. This model was used to determine population denominators and person years. New TB disease rates were calculated from the proportion of new cases in the HIV-positive and negative populations in the community. Retreatment TB rates were calculated for HIV-negative patients using follow-up time from new TB episode to first retreatment episode or to censoring date (31 December 2010), excluding patients who died or transferred out. The time interval between episodes was calculated as the difference between treatment start dates of two successive episodes.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Bivariate analyses employed Wilcoxon rank sum and chi2 tests, as appropriate. Trends in the proportions of retreatment cases, HIV-positive TB patients and patients on ART were assessed using Cox-Stuart test for trend18. Cox proportional hazards models were developed to assess time intervals between successive TB diagnoses, stratified by HIV and ART status, TB outcomes and matched or non-matched Mtb strains. Multiple logistic regression models were developed to examine factors associated with matched and non-matched Mtb strains.

Results

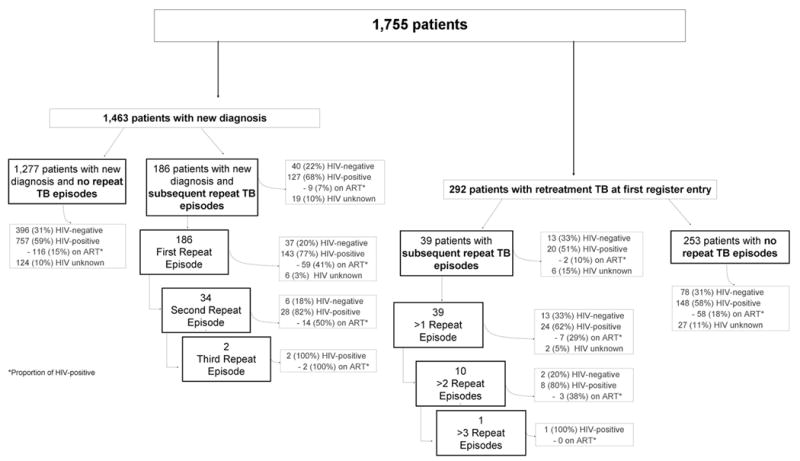

Over the study period 1,755 adults had 2,027 notified cases of TB (Table 1): 72% (1,463) were new TB cases, and 28% (564) retreatment TB. Of 564 retreatment cases, 272 followed a previous case recorded in the register and 292 were retreatment cases at first entry in the community TB register, having received treatment for earlier TB case whilst resident outside the community (Figure 1).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of adult TB cases from 2001 to end 2010.

| 2001 N=111 |

2002 131 |

2003 160 |

2004 176 |

2005 252 |

2006 231 |

2007 228 |

2008 238 |

2009 268 |

2010 232 |

TOTAL 2,.027 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) | 32 (26-40) | 33 (27-40) | 33 (26-40) | 32 (26-39) | 32 (27-41) | 30 (25-37) | 33 (27-38) | 33 (26-41) | 33 (28-41) | 34 (28-41) | 32 (27-40) |

| Gender (Male) | 61 (55%) | 64 (49%) | 87 (54%) | 100 (57%) | 133 (53%) | 124 (54%) | 128 (56%) | 127 (53%) | 152 (57%) | 128(55%) | 1,104 (54%) |

| New case | 85 (77%) | 99 (76%) | 116 (73%) | 121 (69%) | 184 (73%) | 169 (73%) | 170 (75%) | 165 (69%) | 194 (72%) | 160 (69%) | 1,463 (72%) |

| Retreatment Case | 26 (23%) | 32 (24%) | 44 (27%) | 55 (31%) | 68 (27%) | 62 (27%) | 58 (25%) | 73 (31%) | 74 (28%) | 72 (31%) | 564 (28%) |

| HIV unknown | 23 (21%) | 22 (17%) | 25 (16%) | 16 (9%) | 21 (8%) | 25 (11%) | 21 (9%) | 19 (8%) | 6 (2%) | 6 (3%) | 184 (9%) |

| HIV Negative | 42 (38%) | 39 (30%) | 50 (31%) | 52 (30%) | 81 (25%) | 58 (24%) | 61 (27%) | 69 (29%) | 65 (24%) | 68 (29%) | 585 (29%) |

| HIV Positive | 46 (41%) | 70 (53%) | 85 (53%) | 108 (61%) | 150 (60%) | 148 (64%) | 146 (64%) | 150 (63%) | 197 (74%) | 158 (68%) | 1,258 (62%) |

| HIV positive on ART** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8(3.%) | 20 (8%) | 39 (16%) | 38 (16%) | 35 (15%) | 46 (19%) | 52 (22%) | 238 (19%) |

Number and proportion of HIV-positive on ART at time of TB diagnosis

Figure 1. Consort diagram of TB patients.

The demographics and HIV status of TB cases stratified by year are reported in Table 1. Overall 942 (64%) of new cases were sputum smear and/or culture positive and 407 (72%) of retreatment cases were sputum smear and/or culture positive. In the community, there were an estimated 24,289 HIV-positive person years and 77,406 HIV-negative person years over the 10 years.

New TB cases

In total 1,320 (90%) of new TB patients received HIV testing, of which 884 (60%) were HIV-positive and125 (14%) were on ART.

Over the 10-year period new TB was diagnosed in 3.6% and 0.6% of the HIV-positive and HIV-negative populations respectively (odds ratio [OR]: 6.7; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.9-7.5; p<0.001).

Treatment outcomes were as follows: 1,129 (77%) patients completed the TB treatment course, 126 (9%) were transferred out, 93 (6%) interrupted treatment, 92 (6%) died, 11 (1%) failed TB treatment and 12 patients remained on treatment at the time of analysis. HIV-positive TB patients had a higher death rate compared to HIV-negative patients (p<0.001). However, among survivors, there was no difference in treatment completion (p=0.65), transfer out (p=0.51) or treatment interruption/failure (p=0.48) by HIV status.

Retreatment following new TB diagnosis

Over the ten-year study period, 186 of the 1,463 new TB patients had 222 repeat TB episodes (Figure 1). Retreatment TB occurred in 16% (95% CI: 14-19%) of HIV-positive and 8% (95% CI: 6-12%) of HIV-negative patients (OR: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.4-3.1; p<0.001). The median follow-up time for HIV-negative new cases was 4.0 years, and the retreatment rate was 2.4 cases/100 person years. New patients with a subsequent episode of TB had more treatment interruptions/failures at their first TB diagnosis (p<0.001), were more likely to be HIV-positive (p=0.01), less likely to be on ART at the time of their first TB diagnosis (p=0.02) and were older (p=0.04) than those without subsequent retreatment TB.

Retreatment TB at first TB register entry

Of 292 retreatment patients recorded as such at first entry in the TB register, 39 had 50 repeat episodes (Figure 1). Compared to the 186 retreatment patients whose retreatment TB followed a new TB diagnosis in the community, age (p=0.09), gender (p=0.66) and treatment outcomes (p=0.21) were similar, but the 292 retreatments were less likely to be HIV-positive (p=0.001) or on ART (p<0.001).

All retreatment TB

A total of 478 retreatment patients had 272 repeat episodes (272 retreatment pairs). HIV testing was performed in 97% of retreatment episodes with 78% testing HIV-positive, of which 42% were on ART at retreatment diagnosis.

Treatment outcomes were: 401 (71%) completed treatment, 61 (11%) interrupted treatment, 45 (8%) transferred out, 44 (8%) died, 3 (2%) failed treatment and 10 patients remained on treatment. Three percent (n=16) had MDR-TB, and no cases of XDR-TB were identified.

Timing of Repeat TB episodes

The median time interval between initial and the first retreatment episode was 1.6 years (IQR: 0.9-2.9 years). There was no statistical difference in median time interval between first retreatment and subsequent retreatment episodes (p=0.74).

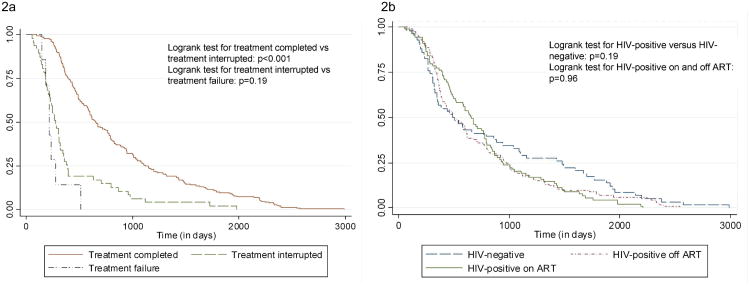

Figure 2a shows patients who interrupted or failed treatment had significantly shorter time between episodes compared to patients who completed initial treatment (p<0.001). Figure 2b shows the time difference between episodes by HIV status. There was no statistical difference in the time between repeat TB episodes for HIV-negative patients, HIV-positive patients (p=0.19) or in the time between episodes for HIV-positive patients on and off ART (p=0.96).

Figure 2. Time to second diagnosis by (a) treatment outcome and (b) HIV status.

Genotyping analysis

Of the 272 retreatment pairs, 153 (56%) had positive sputum for both episodes. Cultures were available for RFLP analysis on 52 (34%) and 40 pairs had genotypes identified for both episodes.

Patients with genotype data did not differ from those without data in terms of age (p=0.90), gender (p=0.40), new versus retreatment TB (p=0.67) or HIV status (p=0.36). Patients with genotype data were more likely to be on ART (p=0.02); this association did not persist when adjusted for year (p=0.83).

Of these 40 pairs, 19 (48%) had matching Mtb strains at both diagnoses. Table 2 shows the demographic, clinical and TB characteristics of the 40 pairs.

Table 2. Genotyping pairs of sputum-positive retreatment patients.

| Matching pairs (n=19) | Non-matching pairs (n=21) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at first diagnosis (IQR) | 34 (24-37) | 32 (27-39) | 0.92 |

| Median age at second diagnosis (IQR) | 34 (28-41) | 34 (32-42) | 0.53 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 10 (53%) | 14 (67%) | 0.37 |

| Female | 9 (47%) | 7 (33%) | |

| HIV status at second diagnosis | |||

| HIV-negative | 8 (44%) | 4 (20%) | 0.11 |

| HIV-positive* | 10 (56%) | 16 (80%) | |

| On ART at time of second TB diagnosis | 2 (20%) | 10 (63%) | 0.03 |

| Median time on ART at time of second TB diagnosis (IQR) | 306.5 (107-506) | 660 (329-864) | 0.13 |

| TB characteristics | |||

| Median days between diagnoses (IQR) | 347 (291-437) | 846 (433-1422) | 0.006 |

| TB treatment completion/cure of first TB diagnosis | 10 (53%) | 16 (84%) | 0.04 |

| TB treatment interruption of first TB diagnosis** | 9 (47%) | 3 (16%) |

HIV status unknown for 2 patients

2 patients excluded: transferred out, therefore outcome unknown

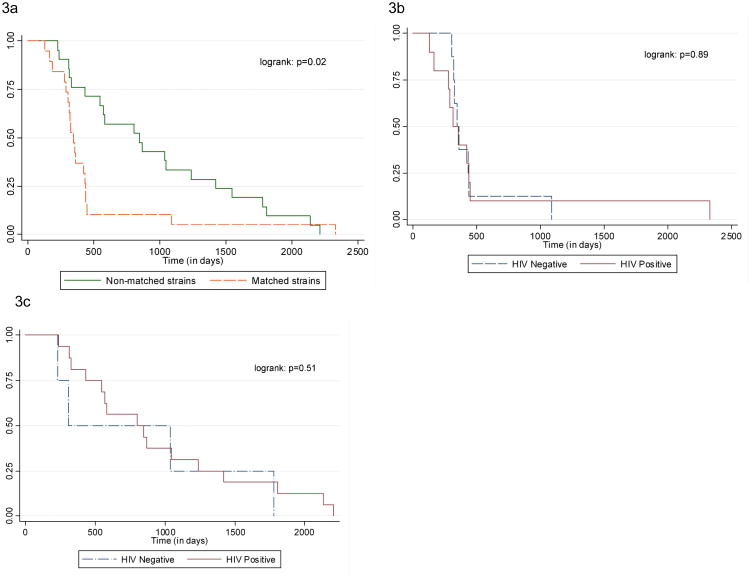

There was no difference in age or gender of matched and non-matched pairs. Patients who interrupted their first treatment were more likely to have matching Mtb strain compared to those who had completed TB treatment (p=0.04). Patients with Mtb matching strains had shorter time intervals between episodes compared to patients with non-matching strains (p=0.02; Figure 3a). With increasing time from first episode, an increasing proportion of retreatment cases were due to re-infection: 29% in first year, 44% in second year, 83% in third year and 88% more than three years after first episode (p=0.002).

Figure 3. Comparison of time interval between successive TB episodes. Figure 3a: Matching strains and non-matching strains in all 40 patients. Figure 3b: Matched strains by HIV status; Figure 3c: Non-matched strains by HIV status.

All HIV-positive patients and HIV-positive patients on ART were more likely to have non-matched strains (p=0.01 and p=0.03), and HIV-negative patients matched strains (p<0.001). There was no difference in the time interval between successive episodes by HIV status (p=0.22), or between matched and non-matched strains by HIV status (p=0.89 and 0.51 respectively; Figures 3b and 3c).

Among the 40 retreatment cases, four of the retreatment samples were MDR-TB, with three following previously completed TB treatment, and one a previous treatment interruption. In two of the previously completed treatment cases, the MDR-TB strain did not match the Mtb strain from the previous TB diagnosis, and in the third case the initial strain and the subsequent MDR-TB strain were identical.

Discussion

In this high TB and HIV burdened community we found that retreatment TB consistently contributed over a quarter of TB disease burden over a ten-year period. The overall risk of retreatment TB was two-fold higher in HIV-positive compared to HIV-negative patients.

RFLP analysis demonstrated that retreatment TB was predominantly due to exogenous re-infection. TB reactivation occurred mainly early following initial TB episode and was associated with previous treatment interruption or failure.

Re-infection predominated in patients who had completed initial TB treatment and was associated with a longer time interval between episodes.

High rates of exogenous re-infection are in keeping with other studies from developed and developing countries3;5;19-21. Our study showed that more than 75% of retreatment TB occurred in patients who had successfully completed their first course of TB treatment. Therefore in this setting with high transmission rates12 repeated TB disease was not primarily due to insufficient treatment, but due to a high risk of re-infection and subsequent rapid progression to TB disease22.

HIV-positive patients on ART were more likely to experience exogenous re-infection TB, compared to both HIV-negative patients and HIV-positive patients off ART. This is the first study to show re-infection is the predominant cause of retreatment TB in ART patients.

Patients with retreatment TB at first entry in the community TB register were less likely to be HIV-positive and less like to be on ART compared to retreatment patients following a new TB diagnosis in the community. These patients migrated into the study community between their first TB episode and the retreatment diagnosis and they may have immigrated from areas with lower HIV prevalence and ART availability. Furthermore lower ART treatment availability at the time of their first retreatment diagnosis may also partially explain the lower ART usage in this group.

The time interval between repeat episodes was not impacted by HIV or ART. The lack of association between time intervals between successive diagnoses and HIV status is a somewhat counter-intuitive finding, warranting further study.

The rates of MDR-TB in this study were low and occurred in a variety of different Mtb strains. MDR-TB was not identified among the new TB cases, and most retreatment MDR-TB was due to exogenous acquisition.

A limitation of the study was that genotyping data were not available on all retreatment pairs. This was predominantly due to lower sample collection rates early in the study13. Incomplete sampling may have introduced selection bias. However, all known characteristics and confounders were assessed and found to be equally distributed across the two groups. The one exception is the increased likelihood of genotype data being available for patients on ART. However, this difference was not statistically different when adjusted for time and is therefore probably due to the increasing coverage of ART coinciding with improved specimen collection for this study.

It is possible that patients with matching strains at successive diagnoses had been re-infected with the same strain, particularly if infections arose from a common source. Such misclassification would result in an underestimation of re-infection. Furthermore, mixed infection (more than one Mtb strain identified in a single TB episode) was identified in only 1% of study specimens. Therefore it is unlikely that mixed infections resulted in overestimation of re-infection.

In conclusion, retreatment TB contributed substantially to disease burden. Time to retreatment diagnosis did not differ by HIV status, and further studies into this finding are required. Regardless of HIV status, retreatment TB occurring more than two years after original diagnosis is most likely to be due to re-infection. Retreatment disease in HIV-negative patients was predominantly due to reactivation of previous infection, and as such reflects the efficacy of the TB control program. In contrast, retreatment disease in HIV-positive patients, both on and off ART, was predominantly due to re-infection and is therefore an indicator of the force of Mtb transmission.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: National Institutes of Health (Comprehensive Integrated Programme of Research on AIDS) grant 1U19AI053217 to K.M., L.G.B. and R.W), and NIH CIPRA grant 1U19AI05321 and NIH RO1 grant AI058736-02 to R.W. The Wellcome Trust Strategic award: Clinical infectious diseases research initiative WT084323MA to KM. National Institutes of Health RO1 AI66046 and RO1 AI 080737 to BK.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Author contributions:

KM: Literature search, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, created figures, manuscript first draft

LGB: Study design, manuscript review

ES: Genotypic analysis, manuscript review

BK: Genotypic analysis, manuscript review

RW: Study design, data interpretation, manuscript review

References

- 1.Garcia-Garcia ML, Small PM, Garcia-Sancho C, Mayar-Maya ME, Ferreyra-Reyes L, Palacios-Martinez M, Jimenez S, Canales G, Quiroz G, Yanez L, Valdespino-Gomez JL. Tuberculosis epidemiology and control in Veracruz, Mexico. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:135–140. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cape Town TB Control Progress report 1997-2003. Health Systems Trust; Cape Town, South Africa: 2004. www.hst.org.za./publications/618. [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Rie A, Warren R, Richardson M, Victor TC, Gie RP, Enarson DA, Beyers N, van Helden PD. Exogenous reinfection as a cause of recurrent tuberculosis after curative treatment. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1174–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verver S, Warren RM, Beyers N, Richardson M, van der Spuy GD, Borgdorff MW, Enarson DA, Behr MA, van Helden PD. Rate of reinfection tuberculosis after successful treatment is higher than rate of new tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1430–1435. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1200OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonnenberg P, Murray J, Glynn JR, Shearer S, Kambashi B, Godfrey-Faussett P. HIV-1 and recurrence, relapse, and reinfection of tuberculosis after cure: a cohort study in South African mineworkers. Lancet. 2001;358:1687–1693. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crampin AC, Mwaungulu JN, Mwaungulu FD, Mwafulirwa DT, Munthali K, Floyd S, Fine PE, Glynn JR. Recurrent TB: relapse or reinfection? The effect of HIV in a general population cohort in Malawi. AIDS. 2010;24:417–426. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832f51cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawn SD, Myer L, Edwards D, Bekker LG, Wood R. Short-term and long-term risk of tuberculosis associated with CD4 cell recovery during antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS. 2009;23:1717–1725. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d3b6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood R, Middelkoop K, Myer L, Grant AD, Whitelaw A, Lawn SD, Kaplan G, Huebner R, McIntyre J, Bekker LG. Undiagnosed tuberculosis in a community with high HIV prevalence: implications for tuberculosis control. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:87–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-759OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middelkoop K, Bekker LG, Myer L, Whitelaw A, Grant A, Kaplan G, McIntyre J, Wood R. Antiretroviral program associated with reduction in untreated prevalent tuberculosis in a South african township. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1080–1085. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0598OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health RoSA. National Tuberculosis Management Guidelines. 2009 http://familymedicine.ukzn.ac.za/Libraries/Guidelines_Protocols/TB_Guidelines_2009.sflb.ashx.

- 11.Middelkoop K, Bekker LG, Myer L, Johnson LF, Kloos M, Morrow C, Wood R. Antiretroviral therapy and TB notification rates in a high HIV prevalence South African community. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:263–269. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820413b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Middelkoop K, Bekker LG, Liang H, Aquino LD, Sebastian E, Myer L, Wood R. Force of tuberculosis infection among adolescents in a high HIV and TB prevalence community: a cross-sectional observation study. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Middelkoop K, Bekker LG, Mathema B, Shashkina E, Kurepina N, Whitelaw A, Fallows D, Morrow C, Kreiswirth B, Kaplan G, Wood R. Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a South African community with high HIV prevalence. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1207–1211. doi: 10.1086/605930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson LF, Kranzer K, Middelkoop K, Wood R. A model of the impact of HIV/AIDS and antiretroviral treatment in the Masiphumelele community; Centre for Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Research working paper; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bifani PJ, Mathema B, Liu Z, Moghazeh SL, Shopsin B, Tempalski B, Driscol J, Frothingham R, Musser JM, Alcabes P, Kreiswirth BN. Identification of a W variant outbreak of Mycobacterium tuberculosis via population-based molecular epidemiology. JAMA. 1999;282:2321–2327. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Embden JD, Cave MD, Crawford JT, Dale JW, Eisenach KD, Gicquel B, Hermans P, Martin C, McAdam R, Shinnick TM. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:406–409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.406-409.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Actuarial Society of South Africa. ASSA2003 AIDS and Demographic model. 2005 http://aids.actuarialsociety.org.za/ASSA2003-Model-3165.htm.

- 18.Cox DR, Stuart A. Some quick sign tests for trend in location and dispersion. Biometrika. 1955;42:80–95. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Small PM, Shafer RW, Hopewell PC, Singh SP, Murphy MJ, Desmond E, Sierra MF, Schoolnik GK. Exogenous reinfection with multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in patients with advanced HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1137–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304223281601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caminero JA, Pena MJ, Campos-Herrero MI, Rodriguez JC, Afonso O, Martin C, Pavon JM, Torres MJ, Burgos M, Cabrera P, Small PM, Enarson DA. Exogenous reinfection with tuberculosis on a European island with a moderate incidence of disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:717–720. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.2003070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golub JE, Durovni B, King BS, Cavalacante SC, Pacheco AG, Moulton LH, Moore RD, Chaisson RE, Saraceni V. Recurrent tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. AIDS. 2008;22:2527–2533. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328311ac4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daley CL, Small PM, Schecter GF, Schoolnik GK, McAdam RA, Jacobs WR, Jr, Hopewell PC. An outbreak of tuberculosis with accelerated progression among persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. An analysis using restriction-fragment-length polymorphisms. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:231–235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201233260404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]