Abstract

Purpose

Most studies characterizing antitumor properties of iNKT cells have used the agonist, α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer). However, α-GalCer induces strong, long-lasting anergy of iNKT cells, which could be a major detriment for clinical therapy. A novel iNKT cell agonist, β-mannosylceramide (β-ManCer), induces strong antitumor immunity through a mechanism distinct from that of α-GalCer. The objective of this study was to determine whether β-ManCer induces anergy of iNKT cells.

Experimental design

Induction of anergy was determined by ex vivo analysis of splenocytes from mice pre-treated with iNKT cell agonists as well as in the CT26 lung metastasis in vivo tumor model.

Results

β-ManCer activated iNKT cells without inducing long-term anergy. The transience of anergy induction correlated with a shortened duration of PD-1 upregulation on iNKT cells activated with β-ManCer, compared with α-GalCer. Moreover, while mice pretreated with α-GalCer were unable to respond to a second glycolipid stimulation to induce tumor protection for up to two months, mice pretreated with β-ManCer were protected from tumors by a second stimulation equivalently to vehicle-treated mice.

Conclusions

The lack of long-term functional anergy induced by β-ManCer, which allows for a second dose to still give therapeutic benefit, suggests the strong potential for this iNKT cell agonist to succeed in settings where α-GalCer has failed.

Translational Relevance

Activation of iNKT cells with α-galactosylceramide was very successful in preclinical mouse models of cancer; however, its success in clinical trials has been very limited. It has been very well-documented, that once iNKT cells are activated with α-galactosylceramide, they remain unresponsive to restimulation for months. This functional anergy could be a contributing factor to the failure of α-galactosylceramide clinically, as most therapeutics require multiple dosing to achieve maximum benefit. Here, we report that a different iNKT cell agonist, β-mannosylceramide, which is capable of inducing tumor immunity similarly to α-galactosylceramide but by a different mechanism, does not induce anergy. This suggests that β-mannosylceramide has the potential to work well clinically since it can be given in multiple doses without inducing anergy.

Keywords: NKT, CD1d, tumor immunology, immunotherapeutics, anergy

Introduction

Natural killer T (NKT) cells are a unique lymphocyte population expressing phenotypic and functional characteristics of both T and natural killer (NK) cells (1, 2). They express true T cell receptors (TCR) that recognize antigens presented by a non-classical MHC class Ib molecule CD1d. NKT cells can be subdivided into at least two distinct groups, type I and type II, based on TCR expression (3). Type I or invariant NKT cells (iNKT) cells express an invariant TCR α chain, Vα14-Jα18 in mice (Vα24-Jα18 in humans), and utilize a limited Vβ repertoire (Vβ2, 7, and 8.2 in mice and Vβ11 in humans). Unlike conventional T cells that recognize peptide antigens, NKT cells mainly recognize glycolipid antigens. The prototypical antigen for iNKT cells is α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer), which has been shown to be a potent agonist for iNKT cells in both mice and humans (4–6). Upon TCR ligation, iNKT cells rapidly produce large amounts of various cytokines, such as IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-13, and TNF-α, and have been shown to induce immunity against tumors and pathogens through the activation of effector cells such as macrophages, NK and CD8+ T cells (7–10).

iNKT cells have been found to induce potent antitumor immune responses in many different mouse tumor models (10–16). These preclinical studies prompted several human clinical trials with α-GalCer, which to date have had limited success (reviewed in (17)). One potential problem for using α-GalCer to induce clinical responses is the induction of iNKT cell anergy. For conventional T cells, anergy is characterized by impaired proliferation and cytokine production following chronic TCR signaling or signaling in the absence of costimulation (18). In contrast, a single injection of α-GalCer induces iNKT cells to become anergic and unable to produce the same response to restimulation for more than 2 months (19, 20). Multiple injections of α-GalCer do not completely inhibit all cytokine production but instead skew the cytokine response towards Th2 (21), which may not be beneficial in the tumor setting since α-GalCer relies on IFN-γ to induce tumor protection (8, 9, 16).

Recently, we described a new antigen for iNKT cells, β-mannosylceramide (β-ManCer), which contains the same ceramide structure as α-GalCer with a β-linked mannose sugar instead of an α-linked galactose (12). Like α-GalCer, β-ManCer activates iNKT cells to induce an antitumor immune response; however, unlike α-GalCer, which requires IFN-γ for tumor elimination, β-ManCer can protect in the absence of IFN-γ and instead requires TNF-α and nitric oxide synthase, suggesting that β-ManCer is the first representative of a new class of agonists for iNKT cells that protect by a different mechanism. While β-ManCer induced tumor protection comparable with that induced by α-GalCer, other markers of cell activation such as cytokine production and upregulation of activation markers were markedly lower following activation with β-ManCer. Since long-term anergy induction by α-GalCer may be a result of strong activation of iNKT cells, and β-ManCer did not seem to be as strong an inducer of activation of iNKT cells as α-GalCer, we hypothesized that it might not induce the same long-term anergy of iNKT cells as observed following activation with α-GalCer. In assessing β-ManCer for possible clinical development, we investigated whether its use also was limited by induction of anergy.

In this study, we demonstrate that β-ManCer does not induce long-term anergy of activated iNKT cells. Instead, iNKT cells activated by β-ManCer are able to respond to restimulation more quickly after the first stimulus and to protect against cancer in vivo even after prior treatment with β-ManCer. The lack of anergy induction is correlated with the level of PD-1 expression on iNKT cells. Because β-ManCer, unlike α-GalCer, activates iNKT cells without inducing a strong persistent anergy, it may have the potential to be repeatedly administered in human cancer patients to induce more effective tumor elimination.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female BALB/c mice were purchased from Animal Production Colonies, Frederick Cancer Research Facility, NCI. Female mice older than 6 weeks of age were used for all experiments. All experimental protocols were approved by and performed under the guidelines of the National Cancer Institute’s animal care and use committee.

Reagents

α-GalCer (KRN7000) was purchased from Funakoshi (Tokyo, Japan). β-ManCer was synthesized as described previously (12).

Cell lines

The CT26 colon carcinoma cell line was maintained as previously reported (12)

In vitro proliferation and cytokine secretion assay

Unless otherwise indicated, mice were injected with 2 µg (approximately 2.4 nmol) α-GalCer or β-ManCer or vehicle control (PBS containing 0.01% Tween20) i.p. Two months later, mice were sacrificed and splenocytes were harvested and stimulated with 100 nM α-GalCer or 500 nM β-ManCer or vehicle control. After 48 hours of stimulation, supernatants were collected, and the concentrations of IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-4 were determined by ELISA. For the proliferation assay, 1 µCi of [3H]-thymidine was added to each well during the final 8 hours of a 72-hour culture and [3H]-thymidine incorporation was evaluated with a MicroBeta counter (Perkin Elmer).

In vitro proliferation of Vβ subsets of iNKT cells

Splenocytes were harvested from mice 4 weeks after receiving 2 µg (approximately 2.4 nmol) of glycolipid as described above. Cells were labeled with 0.1 µM CFSE (Invitrogen) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Labeled cells (4 × 106/well of 24 well plate) were stimulated for 3.5 days with glycolipid (100 nM α-GalCer or 500 nM β-ManCer) or vehicle control. At the end of the culture, cells were harvested and stained with PBS57-loaded CD1d tetramer (NIH Tetramer Facility), anti-CD3 (BioLegend) and Vβ2, Vβ7 and Vβ8.1/8.2 (BD Biosciences). The fluorescence of stained cells was measured by FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed by FlowJo (Tree Star).

iNKT cell and DC activation analysis

Mice were injected with 2.4 nmol (approximately 2 µg) α-GalCer or β-ManCer or vehicle control (PBS containing 0.01% Tween20) i.p. Splenocytes were harvested at the indicated time points and stained with PBS57-loaded CD1d tetramer (NIH Tetramer Facility); anti-CD3, CD40, CD69 and, CD86 (BioLegend); PD-1, PD-L1, PD-L2, CD25, CD11b, and CD11c (eBioscience); and CD80 (BD Bioscience). The fluorescence of stained cells was measured by FACSCalibur or LSRII (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed by FlowJo (Tree Star).

In vivo lung metastasis assay

Mice were injected with 2 µg (2.4 nmol) α-GalCer or β-ManCer or vehicle control (PBS containing 0.01% Tween20) i.p. Two months later, 5 × 105 CT26 cells were injected i.v. into the tail vein. Glycolipid (50 pmol, ~42 ng) or vehicle control (0.00025% Tween 20) was injected i.p. within one hour after tumor challenge. Mice were sacrificed 12–16 days after tumor challenge, and lung metastases were enumerated as previously described (22).

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test by using GraphPad Prism software (version 5; GraphPad software). The data were considered significant at p < 0.05. All experiments were repeated at least twice to confirm reproducibility of results.

Results

β-ManCer does not induce strong, persistent anergy

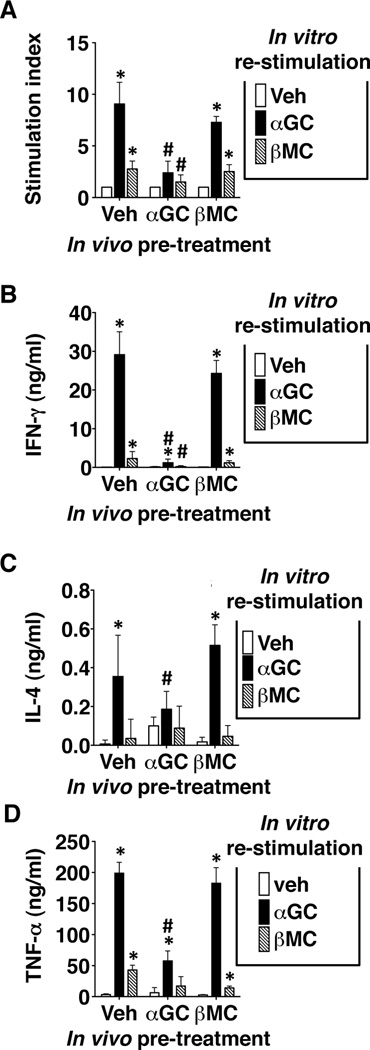

Mice were injected with 2.4 nmol (approximately 2 µg) of α-GalCer or β-ManCer or vehicle i.p., and splenocytes were harvested 1 or 2 months after injection and restimulated in vitro with either α-GalCer or β-ManCer. Even in mice pretreated with vehicle, β-ManCer induced less proliferation, IFN-γ, IL-4, and TNF-α production than α-GalCer (Figure 1A–D) but significantly greater than non-stimulated controls. Consistent with previous reports (23, 24) using the same dose, splenocytes from mice pretreated with α-GalCer were far less able to respond to a second stimulation with either α-GalCer or β-ManCer by any of the indicators measured, and this inability to respond lasted at least 1–2 months. By 1–2 months after glycolipid administration, splenocytes from mice that received β-ManCer could respond just as well to in vitro glycolipid administration as vehicle-control mice. These data demonstrate that unlike α-GalCer, which induces anergy for at least 2 months, at the same timepoint, iNKT cells from mice stimulated with β-ManCer can respond to restimulation similarly to naÔve iNKT cells.

Figure 1.

Unlike α-GalCer, β-ManCer does not induce long-term anergy of activated iNKT cells. Mice were injected i.p. with 2.4 nmol (2 µg) of α-GalCer or β-ManCer or vehicle control. After 2 months, splenocytes were harvested and restimulated in vitro with 100 nM α-GalCer, 500 nM β-ManCer, or vehicle. (A) Proliferation was measured by 3H-thymidine uptake for the last 8 hours of a 72-hour stimulation. Stimulation index was determined by the following calculation: CPM of stimulated wells/CPM of vehicle control. (B) IFN-γ and (C) IL-4 in culture supernatants were measured after 48 hours of stimulation. (D) 1 month after injection of lipids, splenocytes were harvested and restimulated in vitro with 100 nM α-GalCer, 500 nM β-ManCer, or vehicle. TNF-α in culture supernatants was measured after 48 hours of stimulation. Representatives of at least 2 replicate experiments are shown. Bars represent mean±SD; *, statistically significantly different from vehicle control stimulation; #, statistically significant from corresponding stimulation in vehicle pretreated group p<0.05.

Since β-ManCer has weaker potency to induce cytokine production in vitro (12), we used a five times higher concentration of β-ManCer (500 µM) compared to α-GalCer (100 µM) for ex vivo stimulation of spleen cells to be able to obtain measurable cytokine production in the culture supernatant, even though we administered the same amount (2 µg) of glycolipid in vivo. To exclude the possibility that the lower potential of β-ManCer to induce anergy is due to a lower potency to activate iNKT cells, we titrated the dose of α-GalCer to administer in vivo. Although 2.4 nmol of α-GalCer induced the strongest anergy, significant reduction of IFN-γ production was observed with the cells from mice treated with 0.48 nmol (0.4 µg) of α-GalCer, which is five-fold lower than 2.4 nmol, one month after the treatment (supplemental Figure 1). We also compared the effect of 2.4 and 12 nmol (10 µg) of β-ManCer, as 12 nmol is five-fold higher than the dose used for α-GalCer, to administer in vivo to determine the effect on the cytokine production of iNKT cells upon in vitro stimulation 6 weeks later (supplemental Figure 2). There was no significant difference in the production of either IFN-γ or IL-4 of iNKT cells from mice pretreated with the two different doses. Even 12 nmol of β-ManCer did not induce anergy of α-GalCer-reactive iNKT cells, whereas 2.4 nmol of α-GalCer did induce anergy. In this particular experiment, the response of the cells from β-ManCer treated mice was weak, maybe because of the shorter interval (6 weeks) between in vivo treatment and in vitro stimulation compared to most other experiments done at 2 months after pretreatment. In fact, when we examined the kinetics of in vivo response over a 2-month period after in vivo glycolipid treatment, the cells from β-ManCer treated mice weakly responded to β-ManCer at 1, 2 and 4 weeks, whereas those pretreated with α-GalCer remained anergized even at 2 months (supplemental Figure 3; effects most clearly seen in lower panels where data are normalized because of variable background values). In different kinetic experiments, there was some variability in the duration of anergy at the one-month time point for β-ManCer, so that sometimes anergy persisted 1 month and other times not. However, in every experiment, β-ManCer consistently induced anergy at 1–2 weeks, and it was always gone at 2 months, whereas anergy induced by α-GalCer consistently persisted at all time points through the 2-month experiment. Thus, β-ManCer fails to induce long-term anergy even at a 5-fold higher dose than the dose required for α-GalCer, so the difference in the ability to induce anergy between α-GalCer and β-ManCer cannot be overcome by using a higher dose of β-ManCer corresponding to the higher concentrations used for ex vivo stimulation.

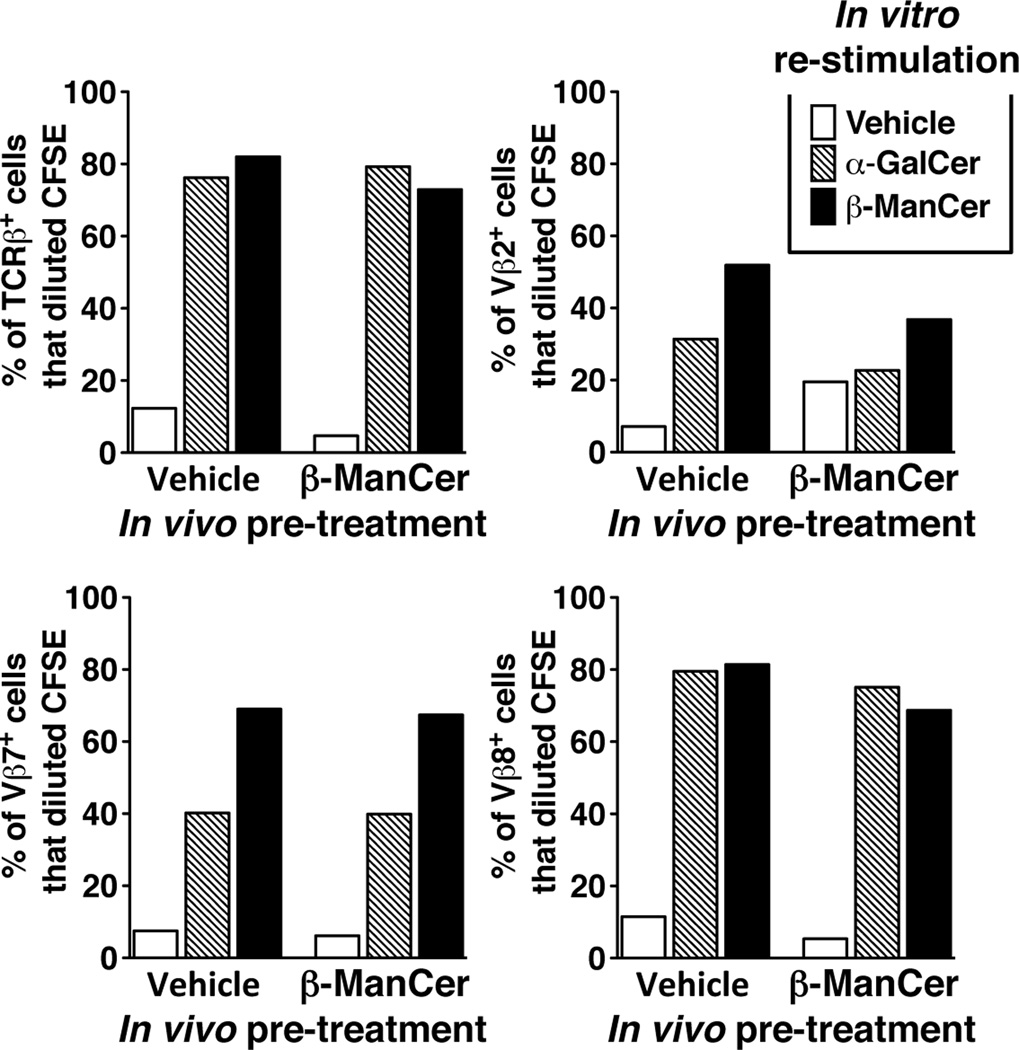

Because iNKT cells can be subdivided according to their Vβ usage, we wanted to rule out the possibility that the lack of prolonged anergy induction by β-ManCer was due to preferential usage of one Vβ subset to recognize β-ManCer. Pretreatment with β-ManCer had little inhibitory effect on proliferation of iNKT cells in response to β-ManCer restimulation. There was no preferential expansion or retention of one Vβ subset, demonstrating that the lack of anergy induced by β-ManCer stimulation of iNKT cells is not due to selective Vβ usage (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Lack of anergy induction by β-ManCer cannot be explained by selective Vβ usage of activated iNKT cells. Mice were injected with 2.4 nmol (2µg) β-ManCer or vehicle control. Splenocytes were harvested at 4 weeks, labeled with CFSE, and restimulated in vitro with 500 nM β-ManCer or vehicle for 3.5 days. At the conclusion of the restimulation, cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry for Vβ expression on iNKT cells. Samples were gated on iNKT cells (defined as CD3intermediateα-GalCer/CD1d tetramer+) expressing TCRβ, Vβ2, Vβ7, and Vβ8.1/8.2. The percentage of Vβ+ iNKT cells that had diluted CFSE was determined by analysis in FlowJo. Bars represent the percentage of Vβ+ iNKT cells in each group that diluted CFSE. Spleens from at least 3 mice were pooled for each group. A representative of 2 reproducible experiments is shown.

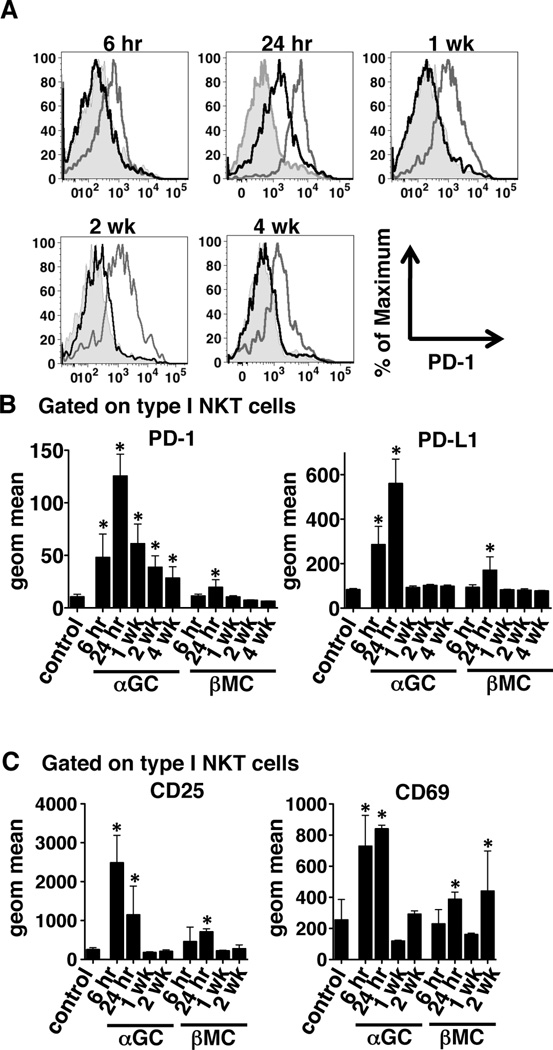

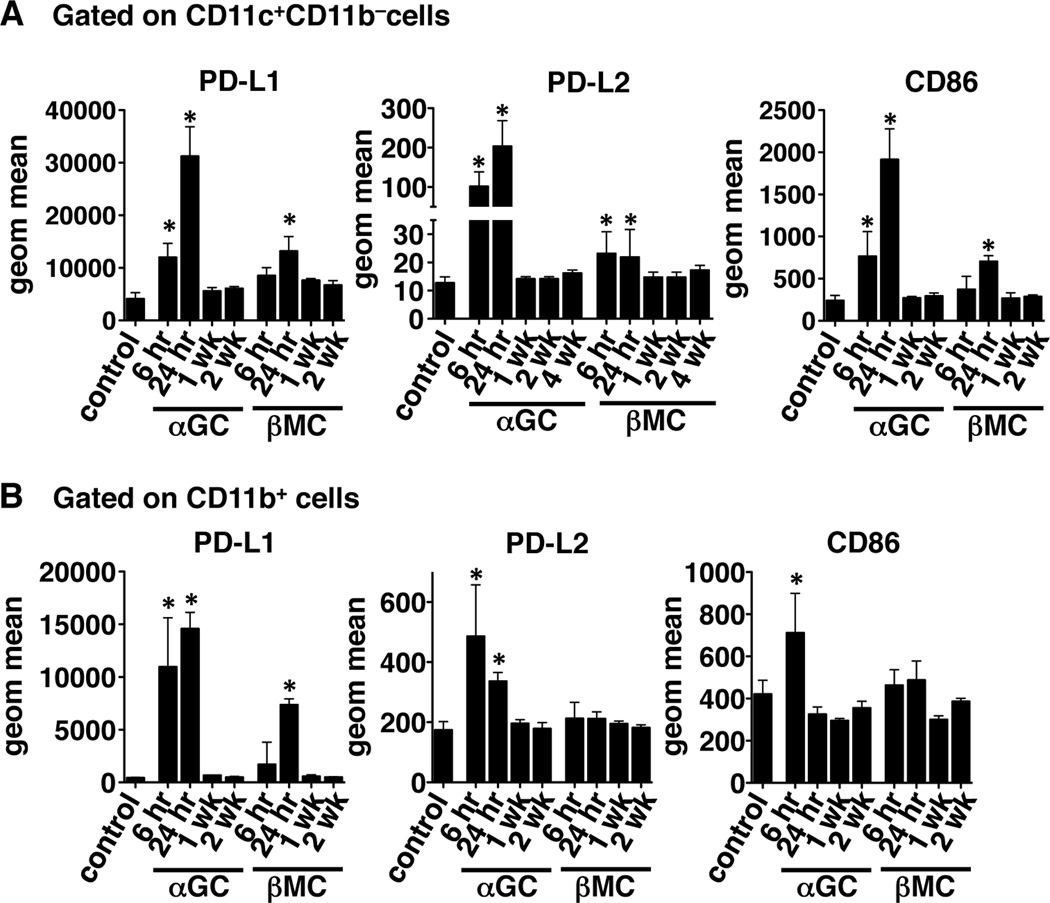

β-ManCer induces less upregulation of PD-1 and activation markers than α-GalCer

Because the upregulation of programmed death-1 (PD-1) and its ligands has been implicated in the induction and maintenance of anergy induced by stimulation of iNKT cells with α-GalCer, we hypothesized that β-ManCer would not induce sustained upregulation of PD-1 and PD-L1 on iNKT cells or PD-L1 and PD-L2 on DCs. As previously reported by Parekh et al (23), α-GalCer induced significant upregulation of PD-1 on iNKT cells, which lasted for at least 4 weeks (Figure 3A & B). PD-L1 was also significantly upregulated on iNKT cells at 6 and 24 hours after glycolipid administration but had returned to baseline by 1 week (Figure 3B). PD-L2 expression on CD11c+CD11b− DCs followed a pattern similar to that of PD-L1 expression on iNKT cells (Figure 4A). β-ManCer induced far less upregulation of PD-1, PD-L1, and PD-L2 (Figure 3 & 4). PD-1 and PD-L1 were significantly upregulated on iNKT cells only 24 hours after glycolipid administration and only to a lesser extent. PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression on DCs was upregulated at 6 and 24 hours, but expression was significantly lower than that induced by α-GalCer. Because PD-1 is also known to be a marker of activated cells (25), we also characterized the kinetics of cell-surface expression of other activation markers on iNKT cells and DCs. CD25 and CD69 were upregulated on iNKT cells 6 hours after α-GalCer stimulation and 24 hours after β-ManCer stimulation (Figure 3C). CD25 and CD69 expression decreased to control levels by 1 week after glycolipid administration, followed by a subsequent increase in CD69 expression at 2 weeks. CD86 expression on CD11c+CD11b−DCs also increased at 6 and 24 hours and returned to baseline by 1 week for both α-GalCer- and β-ManCer-treated mice (Figure 4A); however, the intensity of CD86 expression was greater on DCs from mice given α-GalCer than those given β-ManCer. There were no changes in expression of CD40 or CD80 on DCs following glycolipid administration (data not shown). Since CD1d is expressed on many different types of APCs, and we don’t know which specific cell type is responsible for presenting β-ManCer to iNKT cells, we also determined the expression of PD-L1, PD-L2, and CD86 on CD11b+ cells. Interestingly, the relative increase of PD-L1 following β-ManCer treatment was greatest on CD11b+ cells compared with the other cell types we tested (Figure 4B). However, while α-GalCer induced significant increases in PD-L2 and CD86 expression on CD11b+ cells, β-ManCer did not. These data along with our previous report (12) suggest that β-ManCer does not activate iNKT cells and DCs to the same extent and in the same manner as α-GalCer. The lack of anergy induction may be due to the reduced or lack of sustained expression of PD-1 (or other currently uncharacterized receptors for PD-ligands) and its ligands as well as other activation markers.

Figure 3.

β-ManCer activates but does not induce sustained expression of PD-1 on iNKT cells in vivo. Mice were injected with 2.4 nmol (2 µg) α-GalCer or β-ManCer or vehicle control. At the indicated time points, splenocytes were harvested and stained for analysis by flow cytometry. Samples were gated on CD3intermediateα-GalCer/CD1d tetramer+ cells and assayed for PD-1, PD-L1, CD25, and CD69 expression. (A) Representative histograms of PD-1 expression on gated iNKT cells are shown for each time point. Shaded area = control, gray line = α-GalCer, black line = β-ManCer. (B and C) Geometric mean fluorescent intensity was determined by data analysis in FlowJo for (B) PD-1 and PD-L1 and (C) CD25 and CD69 on gated iNKT cells. Representatives of at least 2 experiments are shown. Bars represent mean±SD of at least 4 mice per group. *, statistically significant vs vehicle control, p<0.05

Figure 4.

β-ManCer induces less expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 and CD86 on antigen presenting cells in vivo. Mice were injected with 2.4 nmol (2 µg) α-GalCer or β-ManCer or vehicle control. At the indicated time points, splenocytes were harvested and stained for analysis by flow cytometry. Samples were gated on (A) CD11c+CD11b− or (B) CD11b+ cells and geometric mean fluorescent intensity of PD-L1, PD-L2, and CD86 was determined by data analysis in FlowJo. Representatives of at least 2 experiments are shown. Bars represent mean±SD of at least 4 mice per group. *, statistically significant vs vehicle control, p<0.05

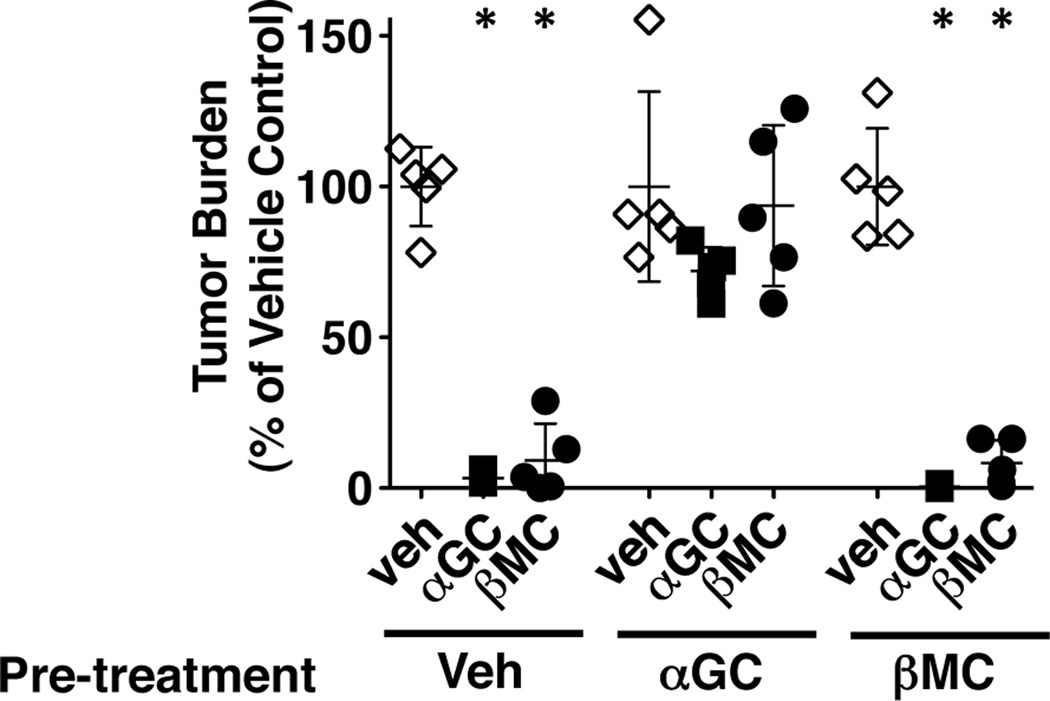

Anergy prevents tumor protection two months after α-GalCer but not β-ManCer treatment

We have demonstrated that after activation with β-ManCer, iNKT cells are able to respond to a second stimulation with either β-ManCer or α-GalCer to induce proliferation and cytokine production. We used an in vivo assay to determine if these cells were still able to function in protecting against tumors. Mice were challenged with syngeneic CT26 tumor cells i.v. 2 months after glycolipid administration and 50 pmol of glycolipid was administered i.p. within one hour of tumor challenge. Both α-GalCer and β-ManCer were able to protect against tumor formation in mice that were pretreated with vehicle or β-ManCer (Figure 5). Neither α-GalCer nor β-ManCer could induce significant protection in mice that were pretreated with α-GalCer, suggesting that the iNKT cells which were activated with α-GalCer are functionally anergic and cannot respond to a second stimulation for at least two months to induce significant protection against CT26 lung tumors. In marked contrast, β-ManCer activation did not lead to functional anergy and the iNKT cells were capable of responding to a second stimulus at both one (data not shown) and two months following activation to induce significant tumor protection.

Figure 5.

iNKT cells primed by β-ManCer, but not α-GalCer, can respond to restimulation to induce tumor protection. Mice were injected with 2.4 nmol (2 µg) α-GalCer or β-ManCer or vehicle control. Two months later, CT26 cells (5 × 105) were injected i.v. into the tail vein of BALB/c wild type and 50 pmol of glycolipids were administered within one hour after tumor challenge. Mice were sacrificed 14 days after tumor challenge and lung metastases were enumerated. Tumor burden was calculated by dividing the number of lung tumors in the treated groups by the mean number of tumor nodules in the respective vehicle control groups. Representatives from at least 2 independent experiments are shown. Symbols represent the tumor burden of individual mice, lines and error bars represent mean±SD. *, statistically significant vs vehicle control, p<0.05

Discussion

α-GalCer has been demonstrated to be very potent at inducing antitumor responses in many mouse models, but clinical trials of α-GalCer in human cancer patients have yet to achieve great success (17). Although anergy of human iNKT cells has not been directly addressed, there were some observations of reduced IFN-γ response in the peripheral blood over repeated doses of α-GalCer (26, 27), and such anergy has been well documented to occur in mice (19, 20, 23, 24, 28), so anergy is a potential hindrance for α-GalCer in the treatment of human cancers. Because anergy cannot be induced in vitro with α-GalCer, we cannot test it in humans short of a clinical trial (data not shown). If iNKT cells are unable to respond to restimulation for months, giving multiple doses of glycolipid may not give any additional benefit. Even if iNKT cells were able to respond to restimulation, a skewing of the cytokine profile away from IFN-γ, as is observed with α-GalCer, may also be problematic. Thus, especially for the treatment of cancer, an ideal agonist would activate iNKT cells without inducing anergy. Weak agonists that do not induce anergy in the past have not been protective either. Here, we report that iNKT cells stimulated with β-ManCer, which is protective, do not remain anergic for months, and are able to respond to restimulation similarly to naÔve iNKT cells within 1–2 months after the first stimulation, and do not exhibit a strong skewing towards Th2. Also, their protective efficacy is not dependent on IFN-γ. Most importantly, β-ManCer activated iNKT cells are able to respond to a second stimulus to induce tumor protection while α-GalCer activated iNKT cells cannot. Since most clinical protocols require multiple doses of therapeutics, it would be beneficial to utilize a compound such as β-ManCer to activate iNKT cells for which multiple doses could be administered.

In all the methods we used to quantitate anergy, iNKT cells from mice treated with β-ManCer never exhibited as strong or durable an anergic phenotype as those from mice given α-GalCer. Due to the unavailability of reagents, it would be very difficult for us to definitively prove that β-ManCer activates the entire subset of iNKT cells that α-GalCer does. The loss of anti-tumor activity of β-ManCer in Jα18−/− mice suggests that β-ManCer-reactive NKT cells use the invariant TCRα chain expressed by α-GalCer reactive iNKT cells (12). In livers, the β-ManCer-loaded CD1d-reactive iNKT cell population is much smaller than that of α-GalCer-loaded CD1d reactive iNKT cells. These data may suggest that β-ManCer reactive iNKT cells might be a small subset of α-GalCer reactive iNKT cells. One can argue that this can be an explanation for the observation that there is no apparent loss of reactivity against α-GalCer in vitro in the splenocytes of β-ManCer treated mice. However, a second dose of β-ManCer still elicits an effect, not only in vitro but also importantly in vivo (see especially the completely undiminished efficacy against cancer of β-ManCer in β-ManCer-pretreated animals in Fig. 5 compared to vehicle-pretreated controls). Thus, even if the repertoire of β-ManCer-reactive iNKT cells is limited, those cells are not becoming anergic after the first dose of β-ManCer, and therefore the hypothetical possibility that not all iNKT cells recognize β-ManCer cannot be an explanation for the lack of anergy induction by β-ManCer. Furthermore, the lack of functional anergy in cancer treatment in vivo 2 months after β-ManCer pretreatment compared to α-GalCer pretreatment implies that whatever portion of iNKT cells react with β-ManCer remain able to respond to β-ManCer to be clinically efficacious in cancer therapy even after pre-exposure to β-ManCer, in contrast to those pretreated with α-GalCer.

While proliferation and cytokine secretion was always less in response to β-ManCer than to α-GalCer, their induction of antitumor immune responses is similar (12), suggesting that such a strong cytokine response by iNKT cells is not required for inducing tumor protection. Thus, while we have demonstrated that β-ManCer induces weak activation of iNKT cells, this may be irrelevant in the context of tumor protection, where β-ManCer is capable of inducing protection without strong activation. It is possible that the less intense signal which β-ManCer provides to iNKT cells prevents the upregulation of molecules that may cause anergy. This quantitative difference together with the qualitative difference of the β-ManCer effects on iNKT cells may be the reason for the lack of long term anergy induction.

Here, the lack of anergy induced by β-ManCer inversely correlated with PD-1 upregulation, which was also much more transient for β-ManCer than for α-GalCer. The immunosuppressive molecule PD-1 and its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, have been implicated in the induction and maintenance of anergy in α-GalCer-activated iNKT cells as upregulation of PD-1 correlates with anergy of iNKT cells (23, 24); however, the exact role of PD-1 and its ligands in α-GalCer-induced anergy remains unclear. A recent report clearly demonstrated that PD-1 is not the sole contributor to anergy in response to α-GalCer stimulation, as anergy still occurred in PD-1 knockout mice (28). In the studies of Parekh et al. and Chang et al., blockade of PD ligands reversed or prevented anergy, suggesting that there may be more receptors for PD ligands which are involved (23, 24). These findings suggest that while the sustained expression of PD-1 following activation with α-GalCer cannot be used as a sole marker of anergy, increased PD-1 expression on iNKT cells does correlate with the anergic phenotype. In this study, we demonstrated that β-ManCer only transiently upregulates PD-1 on iNKT cells at 24 hours after administration. Like α-GalCer, β-ManCer also induces upregulation of PD ligands as well as activation markers on both iNKT cells and DCs, but the expression level is much lower and more transient than that induced with α-GalCer. As discussed above, previous studies have demonstrated that blockade of PD-1 and its ligands can overcome anergy induced with α-GalCer (23, 24). We propose that for the purpose of overcoming iNKT cell anergy, using β-ManCer, or a combination of β-ManCer and α-GalCer, is better than a strategy involving PD-1 blockade, as PD-1 blockade will affect far more cell types and pathways than using these glycolipids which only target iNKT cells.

The lack of anergy induction and lower level of PD-1 induction on β-ManCer activated iNKT cells that we report here might be interpreted as the result of activation of a small fraction of iNKT cells by β-ManCer, based on our previous observation that only a small fraction of iNKT cells can be stained with β-ManCer-loaded CD1d-tetramer (12). However, we believe that this is not the case for the following reasons: First, at the time PD-1 expression was detected in iNKT cells from β-ManCer-treated mice, similar to the cells from α-GalCer-treated mice, the entire iNKT cell population shifted to higher intensity of PD-1 staining, although the magnitude of the shift was smaller in those pre-treated with β-ManCer. If only a fraction of iNKT cells were activated, the majority of cells should not shift. Second, if only a fraction of iNKT cells were activated and were anergized and the rest of the iNKT cells could not respond to β-ManCer, there should be no protection against tumors in β-ManCer-treated mice that had been pre-treated with β-ManCer. Third, our hypothesis is supported by the observation that β-ManCer and α-GalCer induce iNKT cell proliferation measured by CFSE dilution in a similar proportion of the cells in both mouse and human studies (12). Fourth, in the kinetic experiment shown in Supplemental Figure 3, at 2 weeks after pre-treatment, β-ManCer induces transient anergy of iNKT cells responding to α-GalCer. If only a small subset recognized and were anergized by β-ManCer, no anergy even at early time points should have been seen when stimulating with α-GalCer.

We have previously shown that β-ManCer and α-GalCer induce antitumor responses through different mechanisms and synergize when administered together (12), which suggests great potential for the clinical use of β-ManCer. Also, β-ManCer is not a target of natural anti-alpha-Gal antibodies present in humans but not mice, which may limit efficacy of α-GalCer in humans, and it stimulates human iNKT cells in vitro equally well (12). For these reasons, we investigated the potential of β-ManCer for clinical development. We now demonstrate that β-ManCer does not induce a strong skewing of the cytokine profile or long-term anergy of the entire population of iNKT cells, indicating that patients could be treated with multiple doses. These properties make β-ManCer an even more attractive candidate for use in the clinic and suggest that it has the potential to work in cases where α-GalCer does not in treating human cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research and the Gui Foundation. G.S.B. received support from the Medical Research Council (U.K.), the Wellcome Trust (084923/B/08/7), a Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award, and James Bardrick.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest to be disclosed.

References

- 1.Kronenberg M. Toward an understanding of NKT cell biology: progress and paradoxes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:877–900. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taniguchi M, Harada M, Kojo S, Nakayama T, Wakao H. The regulatory role of Valpha14 NKT cells in innate and acquired immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:483–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godfrey DI, MacDonald HR, Kronenberg M, Smyth MJ, Van Kaer L. NKT cells: what's in a name? Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nri1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi E, Motoki K, Uchida T, Fukushima H, Koezuka Y. KRN7000, a novel immunomodulator, and its antitumor activities. Oncol Res. 1995;7:529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motoki K, Morita M, Kobayashi E, Uchida T, Akimoto K, Fukushima H, et al. Immunostimulatory and antitumor activities of monoglycosylceramides having various sugar moieties. Biol Pharm Bull. 1995;18:1487–1491. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behar SM, Porcelli SA. CD1-restricted T cells in host defense to infectious diseases. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;314:215–250. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69511-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berzofsky JA, Terabe M. NKT cells in tumor immunity: opposing subsets define a new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol. 2008;180:3627–3635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. NKT cells and tumor immunity--a double-edged sword. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:459–460. doi: 10.1038/82698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terabe M, Berzofsky JA. The role of NKT cells in tumor immunity. Adv Cancer Res. 2008;101:277–348. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(08)00408-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Sato H, et al. Natural killer-like nonspecific tumor cell lysis mediated by specific ligand-activated Valpha14 NKT cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5690–5693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Konek JJ, Illarionov P, Khursigara DS, Ambrosino E, Izhak L, Castillo BF, 2nd, et al. Mouse and human iNKT cell agonist beta-mannosylceramide reveals a distinct mechanism of tumor immunity. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:683–694. doi: 10.1172/JCI42314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayakawa Y, Takeda K, Yagita H, Kakuta S, Iwakura Y, Van Kaer L, et al. Critical contribution of IFN-gamma and NK cells, but not perforin-mediated cytotoxicity, to anti-metastatic effect of alpha-galactosylceramide. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1720–1727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuji N, Ueda Y, Fujiwara H, Toh T, Yoshimura T, Yamagishi H. Antitumor effect of alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) on spontaneous hepatic metastases requires endogenous interleukin 12 in the liver. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3380–3387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ambrosino E, Terabe M, Halder RC, Peng J, Takaku S, Miyake S, et al. Cross-regulation between type I and type II NKT cells in regulating tumor immunity: A new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol. 2007;179:5126–5136. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smyth MJ, Crowe NY, Pellicci DG, Kyparissoudis K, Kelly JM, Takeda K, et al. Sequential production of interferon-gamma by NK1.1(+) T cells and natural killer cells is essential for the antimetastatic effect of alpha-galactosylceramide. Blood. 2002;99:1259–1266. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motohashi S, Nakayama T. Natural killer T cell-mediated immunotherapy for malignant diseases. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2009;1:108–116. doi: 10.2741/s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz RH. T cell anergy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:305–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parekh VV, Wilson MT, Olivares-Villagomez D, Singh AK, Wu L, Wang CR, et al. Glycolipid antigen induces long-term natural killer T cell anergy in mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2572–2583. doi: 10.1172/JCI24762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uldrich AP, Crowe NY, Kyparissoudis K, Pellicci DG, Zhan Y, Lew AM, et al. NKT cell stimulation with glycolipid antigen in vivo: costimulation-dependent expansion, Bim-dependent contraction, and hyporesponsiveness to further antigenic challenge. J Immunol. 2005;175:3092–3101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burdin N, Brossay L, Kronenberg M. Immunization with alpha-galactosylceramide polarizes CD1-reactive NK T cells towards Th2 cytokine synthesis. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2014–2025. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199906)29:06<2014::AID-IMMU2014>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park JM, Terabe M, van den Broeke LT, Donaldson DD, Berzofsky JA. Unmasking immunosurveillance against a syngeneic colon cancer by elimination of CD4+ NKT regulatory cells and IL-13. International J of Cancer. 2004;114:80–87. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parekh VV, Lalani S, Kim S, Halder R, Azuma M, Yagita H, et al. PD-1/PD-L blockade prevents anergy induction and enhances the anti-tumor activities of glycolipid-activated invariant NKT cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:2816–2826. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang WS, Kim JY, Kim YJ, Kim YS, Lee JM, Azuma M, et al. Cutting edge: Programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 interaction regulates the induction and maintenance of invariant NKT cell anergy. J Immunol. 2008;181:6707–6710. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:515–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishikawa A, Motohashi S, Ishikawa E, Fuchida H, Higashino K, Otsuji M, et al. A phase I study of alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000)-pulsed dendritic cells in patients with advanced and recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1910–1917. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giaccone G, Punt CJ, Ando Y, Ruijter R, Nishi N, Peters M, et al. A phase I study of the natural killer T-cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3702–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iyoda T, Ushida M, Kimura Y, Minamino K, Hayuka A, Yokohata S, et al. Invariant NKT cell anergy is induced by a strong TCR-mediated signal plus co-stimulation. Int Immunol. 2010;22:905–913. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ota T, Takeda K, Akiba H, Hayakawa Y, Ogasawara K, Ikarashi Y, et al. IFN-gamma-mediated negative feedback regulation of NKT-cell function by CD94/NKG2. Blood. 2005;106:184–192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.