Abstract

Background

Use of Depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), norethisterone enanthate (NET-EN) and low-dose combined oral contraceptives (COCs) has been associated with loss of bone mineral density (BMD) in adolescents. However, the effect of using a combination of these methods over time in this age-group is limited. The aim of this cross-sectional study was to investigate BMD in young women (aged 19-24 years) with a history of mixed hormonal contraceptive use.

Study design

BMD was measured at the spine, hip and femoral neck using dual X-ray absorptiometry. Women were classified into 3 groups; 1) injectable users (DMPA, NET-EN or both) (n=40), 2) Mixed COC and injectable users (n=13), and 3) nonuser control. (n=41).

Results

Women in the injectables only user group were found to have lower BMDs compared to the nonuser group at all three sites and there was evidence of a difference in BMD between these two groups at the spine after adjusting for BMI (p=0.042), hip (p=0.025), and femoral neck (p=0.023). The mixed COC/injectable user group BMD values were lower than controls; however, there was no evidence of a significant difference between this group and the nonuser group at any of the three sites.

Conclusion

This study suggests that BMD is lower in long-term injectable users, but not when women have mixed injectable and COC use.

Introduction

The long-acting progestogen injectable contraceptives depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) and norethisterone enanthate (NET-EN) have been found to have a negative effect on bone mineral density (BMD) in adult premenopausal women (Curtis and Martins, 2006; Wanichsetakul et al, 2002; Petitti et al, 2000; Scholes et al, 1999; Cundy et al, 1991) and in adolescents (Beksinska, et al, 2009; Cromer et al, 2008; Rosenburg, et al, 2007; Clark et al, 2006; Scholes et al, 2005; Cromer et al, 2004; Lara-Torre et al, 2004; Scholes et al, 2004; Busen et al, 2003; Cromer et al, 1996). The effect of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) on BMD has been found to be variable with no effect reported in adult premenopausal women (Martins, et al, 2006) but growing evidence that low-dose COCs may be detrimental to BMD in adolescents and young women (Hartard, et al, 2006; Cromer, et al, 2004; Polatti, et al, 1995).

Although recovery of BMD following discontinuation of DMPA is documented in adult pre-menopausal women (Kaunitz, et al, 2006; Scholes, et al, 2002) and in adolescent users (Clark, et al, 2006; Scholes, et al, 2005), concerns regarding bone loss in DMPA users resulted in an US Food and Drug Administration Black Box warning for DMPA stating its use may impair BMD (FDA, 2004). In the UK, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Board (MHRA) suggest that another contraceptive method be used after 2 years of DMPA use (FFPRHC, 2004). Much less information is available on recovery in NET-EN users as it is not as widely used as DMPA and not available in the US or UK. Limited data have found recovery of BMD in adolescent NET-EN users (Beksinska, et al, 2009; Rosenburg, et al, 2007).

More evidence is needed on long-term use of hormonal contraception and, in particular, on women who switch from hormonl injectables to another hormonal method of contraception. The objective of this study was to determine if long-term use of hormonal contraceptives, including mixed use (COCs and/or, DMPA and/or NET-EN), was associated with a change in bone mass in women aged 19-24 years compared to nonusers.

Subjects and methods

This cross-sectional study of young women aged 19-24 years measured BMD in the hip, spine and femoral neck. All the women had been recruited 4-5 years previously into a longitudinal study where the BMD in the distal radius had been measured at 6-month intervals. Details of the longitudinal study methodology and results are described elsewhere (Beksinska, et al, 2009). At the end of the follow-up period, additional funds allowed for 100 single measurements of the central BMD sites providing an opportunity for measurements at other sites. A subsample of women attending their final longitudinal follow-up visit were informed about this additional component of the study at their last cohort visit and were invited to participate. This subsample included all women completing the study over a 5-month period.

At the start of the 5-year longitudinal study, initiators of DMPA, NET-EN, COCs and nonusers of contraception were enrolled from a family planning clinic in Durban, South Africa. All women recruited had no history of hormonal contraceptive use prior to enrolment (n=490). The study cohort was recruited between July 2000 and July 2002, and follow-up continued until April 2006. All DMPA users were started on a regimen of 150 mg every 12 weeks and NET-EN users on 200 mg every 8 weeks. Both DMPA and NET-EN was administered intramuscularly. The COCs used by women included a range of formulations, with almost all (93%) using low-dose formulations containing between 30-40 mcg of estrogen. Women were eligible to participate if they had not lactated or delivered in the past 6 months; were not currently using and had not used medication known to affect calcium metabolism for more than 3 months; and did not have a chronic disease affecting calcium metabolism. At the baseline and follow-up visits, participants’ height, weight and blood pressure were measured using a standard protocol and a questionnaire was administered to elicit information on demographic characteristics, regularity of the menstrual cycle, smoking, diet, exercise and caffeine and alcohol intake. It was from this cohort that the 100 women were recruited for the cross-sectional study reported here.

History of contraceptive use had been recorded in the longitudinal study over the total follow-up period at approximately 6-monthly intervals. Women in the cohort continued the same follow-up schedule even if they stopped, changed or started a contraceptive method. The additional visit to measure the hip, spine and femoral neck BMD was conducted between Oct 2005 and Feb 2006. The DXA equipment used in the cross-sectional substudy to measure hip, spine and femoral neck was a Hologic QDR discovery, version 12,6, Model: Discovery w(s/n) 49369, Hologic. Inc, USA. The DXA equipment was standardized daily using a phantom and accuracy to the standard during the measurement phase was 0.44%.

The characteristics of women in the study were quantified as means ± SD, medians, or percentages. Differences in BMD and weight between contraceptive groups, and the associations between spine, hip and femoral neck BMD and contraceptive group were assessed using one-way analysis of variance and multiple variable linear regression. Data were analyzed using the statistical package STATA V.10, (College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical approval was granted by the University of the Witwatersrand, Human Subjects Research Committee (protocol number M981001), and by the Scientific and Ethical Review Group of the World Health Organization.

Results

A group of 100 women who had completed follow-up in the longitudinal phase agreed to participate in the cross-sectional substudy. Of these, 96 women attended their appointment and 4 women were unable to attend due to work commitments. The contraceptive history of these women varied considerably as women had not been discontinued from the longitudinal study if they changed or stopped a method. Thirty women presented with a history of mixed contraceptive use, including women who had used at least two of the study methods (DMPA, NET-EN, and COCs) in the preceding 4-5 years. Of these 30, 17 women had used both DMPA and NET-EN, 10 had mixed COCs and either DMPA or NET-EN, and three women had used all three methods. Far fewer women presented as exclusive users of one method at the end of the follow-up period (DMPA n=9, NET-EN n=14, COC users n=2). The remaining 41 women were nonusers of hormonal contraception.

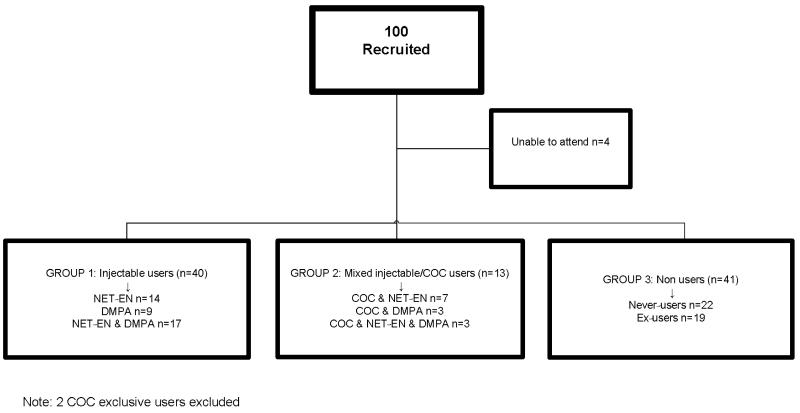

The small number of women who had used one method only, made data difficult to anlayse and we therefore classified the women into three broad groups for analysis, according to their contraceptive history over the previous 4-5 years in the longitudinal component of the study. The first group (n=40) included all users of injectable hormonal contraception, regardless of whether they had used only one or both of the injection types. The second user group comprised of women who mixed COCs with injections (n=13). Finally, the non-hormonal contraceptive users (n=41) included 22 never users of hormonal contraception and 19 ex-users. The ex-users had not used a hormonal method for approximately 2 years or longer and almost all had less than 1 year of lifetime use. These women had started a method on recruitment into the longitudinal study and had subsequently discontinued use. We excluded the two exclusive COC users as they could not be classified into any of the three groups. Figure 1 shows details of the three groups.

Fig 1.

Participant Contraceptive history by study analysis group

Baseline information about these women is summarized in Table 3.4.1. Mean age was approximately 22 years in all groups and the majority of women were African. Few women participated in any regular exercise and only one woman was a current smoker. Alcohol consumption was low across all groups.

Table 3.4.1. Characteristics of subjects aged 19-24 years by contraceptive user group.

| Characteristics | Injectable Users (n=40) |

Mixed COC and injectable users (n=13) |

Nonusers (n=41) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 22.3 (1.4) | 22.1 (1.2) | 22.0(1.6) | 0.7 |

| Ethnicity % | ||||

| African | 90.0 | 100.0 | 97.6 | 0.5 |

| Coloured | 7.5 | 0 | 2.4 | |

| Indian | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ever pregnant % | 12.5 | 0 | 4.8 | 0.23 |

| Mean age at menarche, years(SD) |

13.9 (1.5) | 13.8 (1.2) | 13.7 (1.3) | 0.47 |

| Exercise > once a week (%) | 5.1 | 16.7 | 5.4 | 0.05 |

| Dieted in last 6 months (%) | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.52 |

| Current smoker (%) | 0.0 | 0 | 2.6 | 0.51 |

| Alcohol consumption, units per week % |

||||

| Never | 92.5 | 100.0 | 73.2 | 0.17 |

| 1-2 units | 7.5 | 0 | 22.0 | |

| 3-4 units | 0 | 0 | 4.9 | |

SD=standard deviation

There was evidence that BMD was associated with BMI for all three sites, with one unit of BMI corresponding to an average increase in BMD of 0.010 (0.006-0.015), 0.014 (0.009-0.017) and 0.017 (0.012-0.021) g/cm2 for spine, hip and femoral neck, respectively.

Table 3.4.2 shows mean BMD at the three sites measured. Women in the injectables-only user group were found to have lower BMDs compared to the nonuser group at all three sites. There was some evidence of a significant difference in BMD between the injectable and nonuser groups at the spine (p=0.042), hip (p=0.025), and femoral neck (p=0.023) after adjusting for BMI. In the mixed COC and injectable group, the BMD values were lower than the nonusers at all sites; however, there was no evidence of a difference between this group and the nonusers (spine p=0.54, hip p=0.15, femoral neck p=0.43).

Table 3.4.2. Mean spine, hip and femoral neck BMD by contraceptive user group, relative to nonusers.

| Injectable users (n=40) |

Mixed COC and injectable users (n=13) |

Nonusers (n=41) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| MeanBMDg/cm2 (SD) | |||

| Spine | 0.944 (0.109)(p=0.042) | 0.960(0.094) (P= 0.54) | 0.975 (0.115) |

| Hip | 0.928 (0.116)(p=0.025) | 0.919 (0.099) (P=0.15) | 0.954 (0.102) |

| femoral neck | 0.844 (0.125)(p=0.023) | 0.855(0.101) (P= 0.43) | 0.871 (0.130) |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) (SD) | 26.4 (4.9) (p=0.14) | 25.4 (3.1) (p= 0.71) | 24.9 (4.3) |

BMD=bone mineral density; BMI=body mass index; p-values from regression model adjusting for BMI

Weight in the nonuser group remained similar to that at baseline, whilst women in the injectable user group had gained on average 6.7 kg and the mixed COC/injectable group gained 1.9 kg (data not shown) over the 4-5 year follow-up.

Discussion

Our results show evidence of significantly lower BMD values in the hip, spine and femoral neck, between the adolescent users of injectable hormonal methods and nonusers, but not those women who have used COCs in combination with injectables. The absence of a significant difference in BMD between this group and the nonusers, may be due to the small number in this group (n=13). Over the follow-up period, this mixed-use group used COCs before and after injectable use and some moved between these methods several times. However, this group had less overall injectable exposure over the follow-up period compared to the injectable-only group.

Although we are unable to comment on any specific method, our sample consisted of a representative group of women completing follow-up in the longitudinal study during a specific time period. At the end of our study, the mixed hormonal contraceptive users were found to be far more common than the exclusive users. Few women stayed on one hormonal method and many had discontinued hormonal contraception altogether. Although the study was designed to collect reasons for discontinuation of method, anecdotal reports indicated that various side effects and change in relationship status resulted in breaks and changes in method.

The literature has shown that discontinuation rates amongst adolescent DMPA users are particularly high, and continuation rates as low as 27% at one year have been found in the US (Polaneczky and Liblanc, 1998). In the longitudinal component of our study, there was an incidence of 37% method change per person-year for DMPA and 26% for NET-EN (Beksinska, et al, 2007). Although concerns remain regarding hormonal contraceptive use in adolescents, data indicate that few women are long-term exclusive users of one method of contraception. If mixed users are more prevalent, as was seen in our study, it would be important to include them in studies looking at hormonal contraceptive use and BMD.

Two studies have looked at young women who commenced low-dose COCs after use of DMPA and found they were at risk for loss of BMD (Berenson, et al, 2008; Albertazzi, et al, 2006). Our study could not confirm this finding as our numbers using DMPA followed by COCs was too small. In addition, the ethinyl estradiol (EE) formulations used by the COC users in our study was 30-40 mcg whereas studies that have found a detrimental effect of COCs on BMD have used even lower (20 mcg) EE formulations (Berenson, et al, 2008; Hartard, et al, 2006; Cromer, et al, 2004; Polatti, et al, 1995) The Medicines and Healthcare Product Regulatory Agency, UK (MHRA) guidelines (FFPRHC, 2004) recommend changing from DMPA to another method of contraception after 2 years of use; however, there is no advice as to what would be the most suitable method post-discontinuation. As the body of evidence increases on recovery of BMD in adult and adolescent women post discontinuation of DMPA (Kaunitz, 2008), this recommendation may need to be reviewed and balanced against the benefit of using DMPA as a long-term effective contraceptive. The third edition of the WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive Use (WHO, 2004) states the advantages of using DMPA generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks in relation to bone mineral density. A position paper published in 2006 by the Society of Adolescent Medicine (Society for Adolescent Medicine, 2006) supports the WHO position on DMPA for woman below 18 and above 45 years and states that with existing evidence, the advantages of using DMPA in women below 18 years outweigh the disadvantages.

Limited data on recovery of BMD on cessation of hormonal contraceptive use in adolescents have been reported in exclusive users of DMPA (Clark, et al 2006; Scholes, et al, 2005) and NET-EN (Rosenburg, et al, 2007; Beksinska, et al, 2009). Further evidence is needed to show that any loss of BMD, resulting from hormonal contraceptive use in adolescence, are fully recovered, and peak bone mass is not compromised. Until this time, the recommendations for DMPA and NET-EN use in adolescents will continue to caution long-term use in young women.

Limitations

This study was unable to analyze the individual effects of any of the three hormonal methods used as the sample size of exclusive users was too small for analysis.

References

- [1].Petitti DB, Piaggio G, Mehta S, Cravioto MC, Meirik O. Steroid hormone contraception and bone mineral density: a cross-sectional study in an international population. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;95:736–743. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00782-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Scholes D, Lacroix AZ, Ott SM, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE. Bone mineral density in women using depot medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;93:233–238. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00447-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wanichsetakul P, Kamudhamas A, Watanaruagkovit P, Siripakam Y, Visutakul P. Bone mineral density at various anatomic bone sites in women receiving combined oral contraceptives and depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. Contraception. 2002;65:407–410. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(02)00308-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Curtis KM, Martins SL. Progestogen-only contraception and bone mineral density. Contraception. 2006;73:470–487. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cundy T, Evans M, Roberts H, Waltie D, Ames R, Reid IR. Bone density in women receiving depot medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. BMJ. 1991;303:13–16. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6793.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Scholes D, Lacroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. The association between depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception and bone mineral density in adolescent women. Contraception. 2004;69:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cromer BA, McArdle Blair J, Mahan JD, Zibners BS, Naumovski Z. A prospective comparison of bone density in adolescent girls recieving depot medroxyprogesterone accetate (Depo-Provera), levenogesterol (Norplant), or oral contraceptives. J Pediatr. 1996;29:671–676. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Busen NH, Britt RB, Rianon M. Bone mineral density in a cohort of adolescent women using depot medroxyprogesterone acetate for one to two years. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32:257–259. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lara-Torre E, Edwards CP, Perlman S, Hertweck SP. Bone mineral density in adolescent females using depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2004;17:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cromer BA, Stager M, Bonny A, et al. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, oral contraceptives and bone mineral density in a cohort of adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cromer BA, Bonny A, Stager M, et al. Bone mineral density in adolescent females using injectable or oral contraceptives: a 24-month prospective study. Fertil Steril. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.10.070. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Scholes D, Lacroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. Change in bone mineral density among adolescent women using and discontinuing depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:139–144. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Clark MK, Sowers MR, Levy B. Bone mineral density loss and recovery during 48 months in first-time users of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:1466–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rosenburg L, Zhang Y, Constant D, et al. Bone status after cessation of use of injectable progestin contraceptives. Contraception. 2007;76:425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Beksinska ME, Kleinschmidt I, Smit J, Farley TMM. Bone mineral density in adolescents using norethisterone enanthate, depot-medroxyprogerterone acetate, or combined oral contraceptives for contraception. Contraception. 2007;75:438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Martins SL, Curtis KM, Glasier AF. Combined hormonal contraception and bone health: a systematic review. Contraception. 2006;73:445–469. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hartard M, Kleimond C, Wiseman M, Weissenbacher ER, Felsenberg D, Erben RG. Detrimental effect of oral contraceptives on parameters of bone mass and geometry in a cohort of 248 young women. Bone. 2006;40:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Polatti F, Perotti F, Felippa N, Gallina D, Nappi RE. Bone mass and long-term monophasic oral contraceptive treatment in young women. Contraception. 1995;51:221–224. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(95)00036-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kaunitz AM, Miller PD, Montgomery Rice V, Ross D, McClung MR. Bone mineral density in women aged 25–35 years receiving depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate: recovery following discontinuation. Contraception. 2006;74:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. Injectable hormone contraception and bone density: results from a prospective study. Epidemiology. 2002;13:581–587. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200209000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. [accessed October 2, 2006];Black Box warning added concerning long-term use of Depo-Provera contraceptive injection. 2004 Nov 17; FDA Talk Paper T04-50. http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/2004/ANS01325.html.

- [22].Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care of The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . Statement on MHRA guidance on Depo-Provera for prevention of postmenopausal bone loss. FFPRHC; [accessed October 2, 2006]. 2004. 2004. http://www.ffprhc.org.uk/admin/uploads/Depo_Provera_alert_statement.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Beksinska ME, Kleinschmidt I, Smit J, Farley TMM. Bone mineral density in a cohort of adolescents during use of norethisterone enanthate, depot-medroxyprogerterone acetate, or combined oral contraceptives and after discontinuation of norethisterone enanthate. Contraception. 2009;79:345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Polaneczky M, Liblanc M. Long-term depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Deo-Provera) use in inner-city adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1998;2:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Albertazzi P, Bottazzi M, Steel S. Bone mineral density and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. Contraception. 2006;73:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Berenson AB, Rahman M, Breitkopf CR, Bi LX. Effects of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and 20-microgram oral contraceptives on bone mineral density. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:788–799. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181875b78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kaunitz AM, Arias R, McClung M. Bone density recovery after depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injectable contraception use. Contraception. 2008;77:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].World Health Organisation . Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. Third edition Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health organization, CH-1211; Geneva 27 Switzerland: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Society for Adolescent Medicine Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and bone mineral density in adolescents — the Black Box warning: a position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]