Abstract

We demonstrate effective guidance of neurites extending from PC12 cells in a three-dimensional collagen matrix using a focused infrared laser. Processes can be redirected in an arbitrarily chosen direction in the imaging plane in approximately 30 min with an 80% success rate. In addition, the application of the laser beam significantly increases the rate of neurite outgrowth. These results extend previous observations on 2D coated glass coverslips. We find that the morphology of growth cones is very different in 3D than in 2D, and that this difference suggests that the filopodia play a key role in optical guidance. This powerful, flexible, non-contact guidance technique has potentially broad applications in tissues and engineered environments.

Keywords: Axon guidance, Optical tweezers, Regeneration, Neuronal networks, PC12 cells

1. Introduction

Control over axonal trajectories is a critical component of engineering nerve regeneration and reconnection after injury (Geller and Fawcett, 2002), and is essential for engineering specific connections in in vitro neural networks (Fromherz, 2002). A variety of approaches have been employed to guide extending axons (reviewed in Ehrlicher et al., 2007), but almost all have been employed on two-dimensional or nearly two-dimensional environments. Evidence from a wide range of systems shows that cells are sensitive to the mechanical and structural properties of their surroundings in addition to the biochemical properties. In particular, cell morphology and motility often depend on the rigidity of the substrate on which they move, and whether they are on a flat surface or in a three-dimensional matrix (Balgude et al., 2001; Cukierman et al., 2001, 2002; Flanagan et al., 2002; Pizzo et al., 2005). In vivo guidance for nerve regeneration will require techniques that are effective in the complex three-dimensional environment presented by the extracellular matrix (ECM).

Successful approaches to in vitro neurite guidance include surface micro-patterning of permissive or inhibitory molecules which can confine growth to pre-specified regions of the substrate (e.g. Fromherz, 2002). Micromechanical forces from glass microneedles (Lamoureux et al., 2002) or magnetic microbeads (Fischer et al., 2005) can elicit neurites by applying forces on the cell surface. All of these techniques have some limitations (Fromherz, 2002), and, for the most part, cannot be easily extended to three dimensions (for a review, see Seidlits et al., 2008).

It has recently been shown that weak optical forces, generated by an infrared laser spot placed adjacent to the leading edge of the growth cone of an extending axon, enhance growth into the beam focus and result in guided neurite turns, as well as enhanced outgrowth (Ehrlicher et al., 2002, 2007; Carnegie et al., 2008). Guidance on 2D surfaces has been demonstrated for differentiated PC12 cells, NG108-15 cells, as well as primary rat and mouse cortical neurons (Stuhrmann et al., 2005). Effective guidance can be achieved with a range of laser powers and different IR wavelengths (Stevenson et al., 2006). The mechanism through which the light modulates the direction of outgrowth is not known, but there is some evidence that the optical forces on the filopodia play an important role (Carnegie et al., 2008).

In this study we report on the viability of optical neurite guidance in three dimensions. We analyze the trajectories of neurites from differentiated PC12 cells cultured in a 3D matrix of collagen both with and without optical guidance. PC12 cells are often used as a model system for neural differentiation, and for examining growth cone behavior (Dent and Gertler, 2003).We find that the focused laser beam can reliably produce neurite turning, and that the laser beam dramatically increases the rate of neurite outgrowth. We show that the filopodia of PC12 growth cones cultured in 3D collagen matrices are more prominent than those in 2D environments, and that the lamellipodia are correspondingly reduced. Furthermore, some of the filopodia show tight association with the collagen fibrils. These observations suggest that optical guidance in 3D may operate by assisting in the formation of filopodia-fibril contacts.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

PC12 cells were maintained in DMEM containing 7.5% FBS, 7.5% HS, and100 units Penicillin, 100 µg Streptomycin per ml. Cells were differentiated in media supplemented with 100 ng/mL of NGF. Cells were cultured in media at 37° with 5% CO2 in a humid tissue culture incubator.

2.2. Sample preparation

PC12 cells were plated between two layers of collagen to simulate 3D extracellular matrix (ECM) conditions. Prior to applying collagen to the coverslips, Cell Tak (BD Biosciences) was applied to the coverslip of a 35mm glass bottom culture dish (Mat Tek) in order to ensure adhesion of the collagen. The collagen was prepared from Type I collagen stock derived from rat tail (BD Sciences) diluted with sterile water to give a final concentration of 2mg/ml. Also added were 27 µl of a 7.5% sodium bicarbonate solution per ml of original collagen stock, 1/10 final volume of 10× OptiMEM (Gibco), and 100 units Penicillin, 100 µg Streptomycin, 25 ng Fungizone per ml (Biofluids). NGF was added to the collagen solution for a final concentration of 100 ng/ml.

A thin layer of 15 µl 0.2% collagen was placed in the 14 mm diameter well and allowed to polymerize for 10 min. A 0.2 ml media solution with 1×104–2×104 PC12 cells per well was plated onto the collagen and allowed to settle for an hour. Excess media was removed and 200 µl collagen solution was added on top of the cells and allowed to polymerize, resulting in an approximately 1mm thick gel. After 30min, 2.5 ml of media with 4 nM of NGF was added to each plate.

The PC12 cells were left to differentiate and extend processes for 2–3 days. Cells cultured for more than 4 days were not used in these experiments.

2.3. Live-cell imaging

During imaging, samples were placed in a 37 °C stage-top incubator (Tokai-Hit), with a slow flow of air with 5% CO2 gas (Gas Technology & Services) and in a humid bath. An objective heater (Tokai-Hit) maintains the objective temperature also at 37 °C to reduce temperature gradients within the sample.

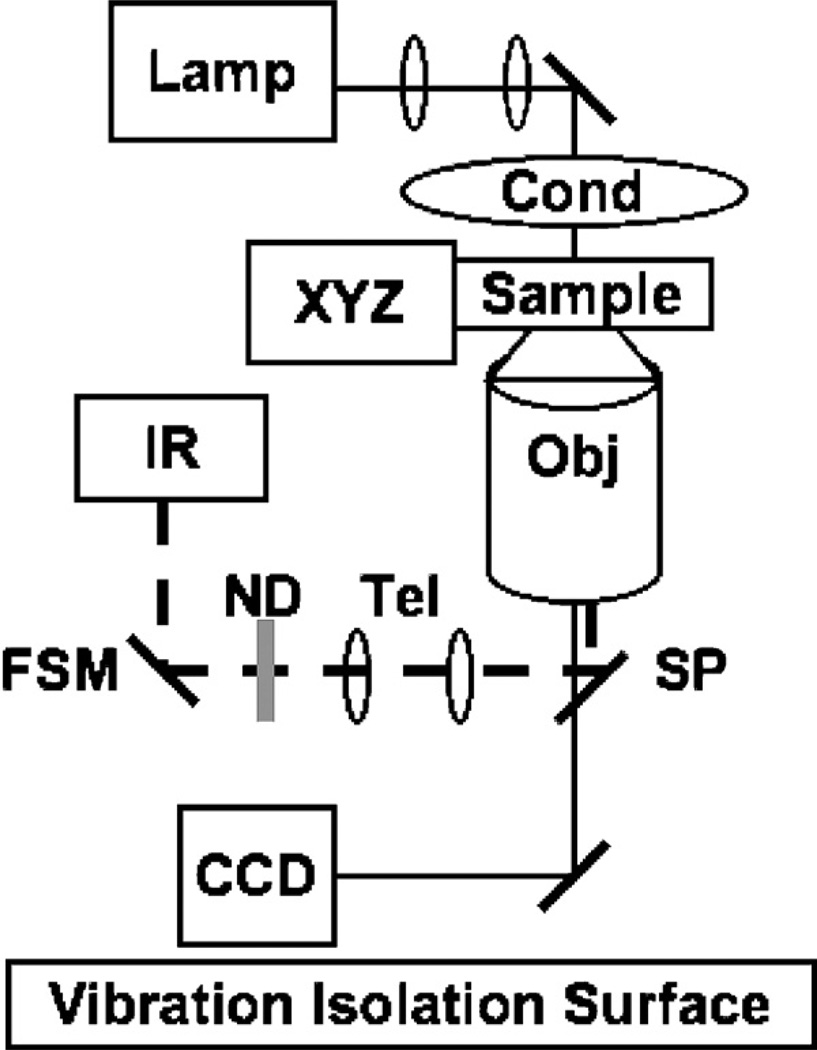

Images were acquired with an inverted Nikon TE2000 microscope and Nikon 100× oil-immersion 1.4 NA objective. Occasionally, an additional intermediate 1.5× magnification was used to give 150× total magnification. Samples were imaged with an Andor iXon DV 887 EMCCD camera. A more detailed diagram of the optical setup is shown in Fig. 1. Using this set-up, filopodia extending from growth cones were resolved in 3D collagen gels at depths up to about 80 µm into the gel. Neurites selected for imaging were typically located about 50 µm into the gel, and extending primarily in imaging plane. Neurites grew in all directions, but those growing largely out of the plane could not be accurately imaged with our microscopy. Image capture was controlled using Slidebook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc.).

Fig. 1.

A schematic of the setup for optical guidance. Microscopy components: CCD: charge coupled device camera (including electron multiplied device(s); Obj: objective; Sample: the imaging sample; XYZ: motorized XY stage and piezoelectric Z control; Cond: condenser; Lamp lamp for brightfield and DIC. The guidance system consists of the following components: IR: infrared laser; ND: neutral density filter FSM: fast steering mirror; Tel: telescope for magnification and creating conjugate planes; SP: short pass mirror.

2.4. Optical guidance

A 1064 nm Ytterbium fiber ring laser (IPG Photonics) with collimated output was used as the light source for the optical trap. This inexpensive option for a 2W IR laser provides a well-collimated Gaussian beam and the convenience of a wavelength matched to readily available, inexpensive laser optics. Even at this long wave-length we can image the reflection of the optical trap off of the coverslip or other glass surface, allowing us to observe the beam position and quality. The laser beam passed through a neutral density filter to attenuate the laser output power. Power outputs ranged between 40 mW and 100 mW, as measured at the focal point of the objective in air with an Oz Optics POM-110 optical power meter.

The position of the laser beam in the focal plane was directed by a fast steering-mirror located at a plane optically conjugate to the rear aperture of the objective. A Galilean telescope was used to create the conjugate plane and to resize the collimated laser beam to fill the back aperture of the objective. Because the beam was collimated as it entered the back aperture of the objective, the focus occurred (approximately) in the focal plane of the objective, which is also the imaging plane. The vertical and horizontal angles of this mirror were independently controlled by voltages from a PCI-6052E I/O card (National Instruments) connected to a BNC-2110 breakout panel (National Instruments) set with a custom program (available upon request) written with LabView (National Instruments).

To bring the laser beam into the optical path of the microscope, we added a stage-height extension (Nikon). In the space created by the extension, we inserted a microscope-quality short pass dichroic (983DCSP, Omega Optical) that transmits more than 90% in the visible light wavelengths and reflects light beyond 1000 nm. The short pass dichroic has finite thickness (about 1 mm) and lies at a 45° angle to the optical axis of the microscope. Therefore, the dichroic displaces the optical axis of the microscope relative to the objective’s optical axis. The thicker the optic, the larger this displacement, and thus the larger the resulting degradation in image quality, and for this reason we selected as thin a suitable dichroic as we could find. The dichroic was mounted in a standard microscope dichroic holder (Omega Optical). We created a custom adapter to position the dichroic precisely within the optical path using a two-axis kine matic tilt-mount (Thorlabs) and a kinematic flip mount (Newport Corporation) to allow repeatable swinging of the dichroic into and out of the optical path. For additional detail on how to build an optical trap, see, for example, Simmons et al. (1996) or Neuman and Block (2004).

Throughout the optical guidance trials, the laser beam was repositioned frequently so that the beam spot remained near the leading edge of the extending neurite. The laser beam could be rapidly repositioned in the x and y directions with an accuracy of approximately 0.1 µm in the sample plane, allowing for precise oscillations of the laser position. At the beginning of a guidance trial, an intended trajectory was chosen, 90° from the current neurite direction. The focus of the beam was positioned on the part of the leading edge that was closest to the intended direction of guidance. The laser beam was placed over the leading edge of the growth cone so that about half of the beam was on top of the leading edge, and was oscillated at the leading edge of the growth cone at a rate of 0.1 Hz. The slow oscillation of the beam simulated a large beam size to make the optical trap more effective. The beam was oscillated with an amplitude of 1–2 µm, in the direction that covered the most area of the growth cone possible and as many filopodia as possible. If the growth cone moved significantly out of the focal plane, the microscope was refocused to obtain a sharp image. The power of the beam was controlled by the choice of neutral density filter, and maintained at a constant value in the range 50–90 mW for each trial. An illustration of the laser beam positioning can be seen in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Representation of laser beam positioning for optical neuronal guidance. The laser beam is placed so that the laser spot overlaps the leading edge of the growth cone, and is positioned at a point on the leading edge closest to the direction of the intended axonal trajectory. In the above illustration, the axon is extending straight down, and the direction of intended guidance is to the right. The beam is placed on the right edge of the growth cone, and oscillated to cover the largest area of the leading edge, resulting in an oscillatory direction about 45° from the intended axonal trajectory.

2.5. Fixed cell labeling and imaging

PC12 cells in the collagen gel were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) PBS for 15 min, followed by permeabilization in 4% PFA PBS 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min. The fixative was removed by washing the cells 5 times for 15min in PBS. Actin filaments were then stained using Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin, 2 units per sample in PBS for 1 h. Excess phalloidin was removed by washing the cells 5 times for 15 min in PBS. Growth cones of the PC12 cells were imaged on a Nipkow spinning disc confocal microscope, using Slidebook to capture the images.

3. Results

3.1. Change in trajectory of unguided neurites

Prior to conducting the guidance trials, control trials were conducted to observe the typical frequency with which neurites changed their trajectory spontaneously. For each control trial, an isolated growth cone at least 30 µm from the coverslip was identified by visual inspection. The neuronal extension was imaged for a 10-min trial period. If filopodial movement was apparent, or the cell advanced at least 1–2 µm in 10 min, the growth cone was presumed to be active. Only active growth cones were included for either control or optically guided trials. The growth cone was then imaged for an additional 30 min to observe the change in neurite trajectory over time.

A summary of the 10 control trials is presented in Fig. 3. In all but one trial, the neurite extensions continued to grow approximately straight, deviating less than 5 ° from their initial direction. (Note that in this assay there is no way to differentiate between axons and dendrites, thus we refer to the guided processes as neurites.)

Fig. 3.

Neurite trajectories in the absence of guidance. Shown above are eight of the ten control trials. The green areas represent the neurite at the beginning of the imaging period, and the magenta overlay shows the position at the end of the 30–40 min trial. The neurites typically extend without changing orientation or don’t extend significantly (scale bar: 10 µm) (for interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article).

3.2. Change in trajectory of optically guided neurites

Candidate growth cones were identified in the same way as the control trials. Once an active growth cone was found, the laser beam was placed over the edge of the growth cone such that half of the beam spot overlapped with the edge of the growth cone, at the point closest to the intended trajectory (chosen to be approximately 90 ° from the direction of outgrowth). As the guided trials progressed, the growth cone normally extended into the focus of the beam. Therefore, the laser beam was repositioned to continue guiding the growth cone in the intended direction, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The laser beam typically needed to be repositioned every 2–3 min. Fig. 4 shows an example of optical guidance in 3D. Optical guidance in 3D is a robust effect: biased growth can be maintained for over 30 min, as seen on 2D surfaces (Ehrlicher et al., 2002, 2007). Eight out of ten optically guided trials displayed large changes in direction over the course of the experiment. The large changes in neurite trajectory may be observed more clearly in the comprehensive summary of the optically guided trials shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4.

Optically induced turning. A 1064 nm laser beam was applied to the edge of an extending PC12 growth cone, causing the extension to grow into the focus of the beam. The growth cone was located about 50 µm above the coverslip. The red circle indicates the approximate position of the laser beam. The beam was oscillated at a rate of 0.1 Hz with a displacement of 1 µm in the x-direction. The laser power at the coverslip was 60mW. This cell extended out of the original focus window, and so the microscope stage was moved up during the capture (for interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article).

Fig. 5.

Summary of Optically Guided Turns. The neurite at the beginning of the imaging period is shown in green, and the magenta overlays show the position at the end of the 30–40 min trial. At the top are the eight successful trials, which clearly exhibit a change in neurite direction. The bottom two trials did not show significant turning: one of these failed guided trials seemed attracted and/or attached to several collagen fibrils in a direction different from the intended direction, while the other failed guided trial did not produce significant advance. (Scale bar: 10 µm) (for interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article).

3.3. Quantification of turning

In order to quantify the extent of turning, a change in angle was calculated for each trajectory, as shown in Fig. 6. The line drawn to indicate the direction of initial and final trajectories and the numerical value of change in neurite trajectory is somewhat subjective, but the change in trajectory in almost all cases was significantly larger than the measurement uncertainty (roughly 5°, depending on the neurite and growth cone morphology).

Fig. 6.

Measurement of the change in neurite trajectory. For each trial, the initial and final images of the trial were extracted, and a line indicating the neurite trajectory was overlaid onto the image. The change in angle between these two lines was found to give a rough estimate of the change in neurite trajectory.

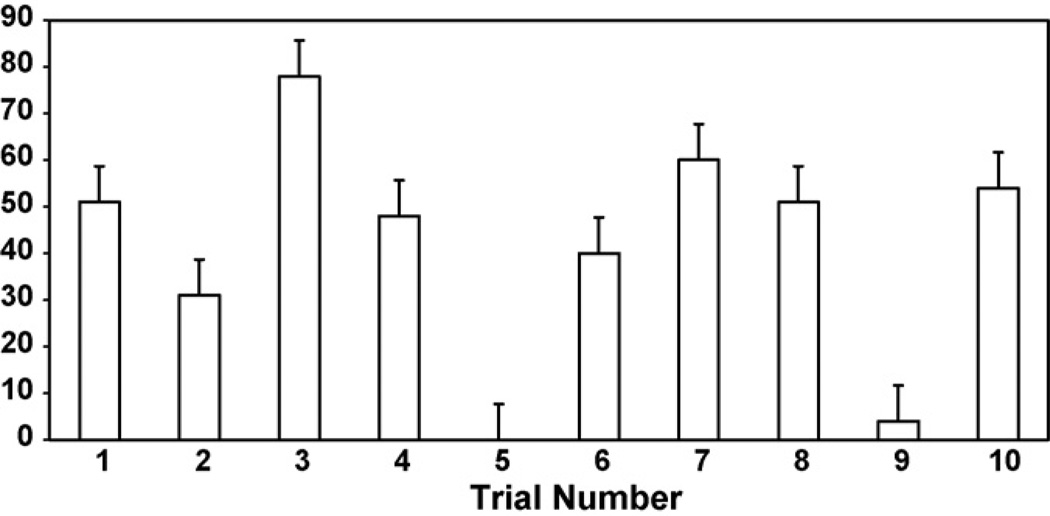

For the control trials, 9 of the 10 trajectories showed deviations of less than 5°. Eight out of ten guidance trials experienced large changes in orientation, always in the intended direction. Two trials experienced no or very little change in direction. The change in the neurite trajectory for the eight successful guided trials was about 52±8 ° (average ± SEM). These results are summarized in Fig. 7

Fig. 7.

Table of results for the change in neurite trajectory of guided trials. Eight of the ten trials showed a change in trajectory well above 5°. For the control trials, nine out ten trials showed changes in direction of less than 5°.

3.4. Difference in growth cone advancement rates

The growth rate over the course of the imaging time was observed to be quite different between the controls and the guided trials. This result was quantified using the Slidebook software to measure the distance between the initial growth cone position and the position of maximum extension, and then dividing that number by the time elapsed to produce an average extension rate. In the controls, the neurites advanced at an average rate of 0.37±0.06 µm/min, while the guided neurites advanced an average of 0.74±0.1 µm/min. This result shows that optical neuronal guidance in 3D substantially increases the rate of neurite outgrowth. Similar increases in growth rate have been observed on 2D substrates (Ehrlicher et al., 2007).

3.5. Growth cone morphology in 3D collagen matrix

While optical guidance appears to be similarly effective in 2D and 3D environments, the structure of the growth cone is quite different. Fig. 8 (left panel) shows a confocal image of actin from fixed, stained PC12 growth cones on a collagen coated coverslip. The same cell type, grown in a 3D collagen matrix, shows dramatically different structure (right panel). The growth cones in 3D are largely devoid of lamellipodia, a prominent feature of cells cultured in 2D. (Neither cell was subjected to optical guidance.) The filopodia in 3D are more prominent than in 2D, sometimes extending long distances and often tightly associated with the collagen fibrils. In other instances, the filopodia only touch the fibrils at their tips.

Fig. 8.

Growth cone has very different morphology in 3D collagen matrix. Left: Actin (green) from growth cones on a coverslip coated with collagen monomers. Right: Actin (green) from growth cone growing in collagen (magenta). Note that cells in 2D have many more filopodia radiating in all directions, while cells growing in 3D have longer, more directed filopodia, with some very long extensions tightly associated with fibrils. Grid spacing is 5 µm (for interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article).

4. Discussion

In this study, we have shown that neuronal optical guidance is effective in a 3D collagen matrix. The length of time that neurites can be guided and the extent of redirection that can be achieved are at least as large as those observed on 2D substrates (Ehrlicher et al., 2002, 2007; Stevenson et al., 2006; Betz et al., 2007). Since the neurites are embedded in a 3D matrix, extension of this technique to fully 3D guidance should be straightforward. Reasonably high resolution 3D growth cone images, such as those obtained by confocal live-cell imaging of fluorescently labeled neurites, could be used to determine laser placement. By adjusting the distance between the lenses in the telescope (Tel in Fig. 1), the divergence of the laser beam as it enters the back aperture of the objective can be changed, changing the focal point of the laser relative to the focal plane of the objective, allowing for 3D steering independent of imaging (Neuman and Block, 2004) It seems likely that the growth cone will be attracted to the focal point of the laser regardless of the direction of extension relative to the optical axis, but this remains to be verified.

In optical neuronal guidance, the optical beam does not function simply as an optical tweezer: either the beam is defocused slightly or, as in our case, oscillated, so that the affected area is large, but the forces are not strong enough to stably trap the growth cone or individual filopodia. The mechanism of optical guidance of extending axons is unknown, but it is possible that the optical forces produce asymmetries in cytoskeletal actin and/or filopodial dynamics, with the latter seeming more likely (Ehrlicher et al., 2007; Carnegie et al., 2008, Daniel Koch and Allen Ehrlicher, private communication). We have observed that growth cones in collagen matrices often show long filopodia closely associated with collagen fibrils, but that their lamellipodia are not as pronounced as on 2D surfaces (Fig. 8). This suggests optical stabilization of the filopodia as a possible mechanism for the guidance that we observe, but further studies are necessary to test this hypothesis.

One possible application for 3D optical axonal guidance is “wiring” in vitro neuronal networks for use as computational devices or biosensors (e.g. Prasad et al., 2006). Currently there is no satisfactory technique for controlling interconnections between neurons or between neurons and electrodes, so that networks are not reproducible and the network topology cannot be optimized for specific applications. A variety of techniques have been developed for in vitro neurite guidance. Surface micro-patterning of permissive or inhibitory molecules with photolithographic techniques can confine growth to pre-specified regions of the substrate (e.g. Fromherz, 2002). Micromechanical forces from glass microneedles (Lamoureux et al., 2002) or magnetic microbeads (Fischer et al., 2005) can elicit neurites by applying forces on the cell surface, but these techniques are not easily adapted to 3D environments.

Gel matrix systems such as collagen provide ideal environments for culturing neurons (Edelman and Keefer, 2005). Neurons typically project processes over large distances, and 2D cultures do not provide the scaffolding that is required for that outgrowth, and do not typically sustain the cell densities that are present in vivo. Rat cortical progenitor cells have been shown to form neural networks in collagen gels (Ma et al., 2004), which exhibit functional synapse formation (O’Shaughnessy et al., 2003). In the human cortex, each neuron makes only a few synaptic connections with neighboring neurons, but forms synapses with thousands of distant neurons. This type of network topology is not observed in 2D cultures, where typically hundreds of synapses are formed with adjacent neurons. The combination of 3D culturing techniques and new technologies to guide neurites has the potential to generate field potentials and other complex behavior observed in vivo and in tissue slices (Edelman and Keefer, 2005).

Some progress has been made towards engineering 3D environments for neuronal networks. Physical confinement of neurons has allowed precise interconnects between specific neurons and a microelectrode, but the neurons tend to escape their cages (Maher et al., 1999). Agarose microchambers created on top of microelectrode arrays with photothermal etching have been used to topographically control networks of rat hippocampal neurons, creating a directed network where signals propagated in a specified direction. (Suzuki et al., 2005). Because optical guidance does not require any modification of the matrix, it is potentially more flexible than either of these approaches and may enable the wiring of complex 3D network topologies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the AFOSR under grant FA9550-07-1-0130. CEG was partially supported by the Georgetown Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program. We have benefited from helpful discussions with members of the Käs lab and additional suggestions on the manuscript from Daniel Koch.

References

- Balgude AP, Yu X, Szymanski A, Bellamkonda RV. Agarose gel stiffness determines rate of DRG neurite extension in 3D cultures. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1077–1084. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz T, Koch D, Stuhrmann B, Ehrlicher A, Käs J. Statistical analysis of neuronal growth: edge dynamics and the effect of a focused laser on growth conemotility. New J Phys. 2007;9:426. [Google Scholar]

- Carnegie DJ, Stevenson DJ, Mazilu M, Gun-Moore F, Dholakia K. Guided neuronal growth using optical line traps. Opt Exp. 2008;16:10507. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.010507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294:1708–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukierman E, Pankov R, Yamada KM. Cell interactions with three-dimensional matrices. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:633–639. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent EW, Gertler FB. Cytoskeletal dynamics and transport in growth cone motility and axon guidance. Neuron. 2003;40:209–227. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman DB, Keefer EW. A cultural renaissance: in vitro cell biology embraces three-dimensional context. Exp Neurol. 2005;192:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlicher A, Betz T, Stuhrmann B, Koch D, Milner V, Raizen MG, Käs J. Guiding neuronal growth with light. PNAS. 2002;99:16024–16028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252631899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlicher A, Betz T, Stuhrmann B, Gögler M, Koch D, Franze K, Lu Y, Käs J. Optical neuronal guidance. Methods Cell Bio. 2007;83:495–519. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)83021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer TM, Steinmetz PN, Odde DJ. Robust micromechanical neurite elicitation in synapse-competent neurons via magnetic bead force application. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:1229–1237. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-5509-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan LA, Ju YE, Marg B, Osterfield M, Janmey PA. Neurite branching on deformable substrates. Neuroreport. 2002;13:2411–2415. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000048003.96487.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromherz P. Electrical interfacing of nerve cells and semiconductor chips. Chem Phys Chem. 2002;3:276–284. doi: 10.1002/1439-7641(20020315)3:3<276::AID-CPHC276>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller HM, Fawcett JW. Building a bridge: engineering a spinal cord repair. ExpNeurol. 2002;174:125–136. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamoureux P, Ruthel G, Buxbaum RE, Heidemann SR. Mechanical tension can specify axonal fate in hippocampal neurons. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:499–508. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Fitzgerald W, Liu QY, O’Shaughnessy TJ, Maric D, Lin HJ, Alkon DL, Barker JL. CNS stem and progenitor cell differentiation into functional neuronal circuits in three-dimensional collagen gels. Exp Neurol. 2004;190:276–288. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher MP, Pine J, Wright J, Tai YC. The neurochip: a new multielectrode device for stimulating and recording from cultured neurons. J Neurosci Methods. 1999;87:45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman KC, Block SM. Optical trapping. Rev Scientific Instrum. 2004;75:2787–2809. doi: 10.1063/1.1785844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shaughnessy TJ, Lin HJ, Ma W. Functional synapse formation among rat cortical neurons grown on three-dimensional collagen gels. Neurosci Lett. 2003;17:169–172. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzo AM, Kokini K, Vaughn LC, Waisner BZ, Voytik-Harbin SL. Extracellular matrix (ECM) microstructural composition regulates local cell-ECM biomechanics and fundamental fibroblast behavior: a multidimensional perspective. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1909–1921. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01137.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad S, Tuncel E, Ozkan M. Association of different prediction methods for determination of the efficiency and selectivity on neuron-based sensors. Biosens Bioelectron. 2006;21:1045–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidlits SK, Lee JY, Schmidt CD. Nanostructured scaffolds for neural applications. Nanomedicine. 2008;3:183–199. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons RM, Finer JT, Chu S, Spudich JA. Quantitative measurements of force and displacement using an optical trap. Biophys J. 1996;70:1813–1822. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79746-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson DJ, Lake TK, Agate B, Gárcés-Chávez V, Dholakia K, Gunn-Moore F. Optically guided neuronal growth at near infrared wavelengths. Opt Exp. 2006;14:9786–9793. doi: 10.1364/oe.14.009786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhrmann B, Goegler M, Betz T, Ehrlicher A, Koch D, Kas J. Automated tracking and laser micromanipulation of cells. Rev Sci Inst. 2005;76:0351051–0351058. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki I, Sugio Y, Jimbo Y, Yasuda K. Stepwise pattern modification of neuronal net-work in photo-thermally-etched agarose architecture on multi-electrode array chip for individual-cell-based electrophysiological measurement. Lab Chip. 2005;5:241–247. doi: 10.1039/b406885h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]