Abstract

The structure of aqueous solutions of methyl β-d-ribofuranoside was investigated by coupling molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and neutron scattering measurements with isotopic substitution. Using a sample of the sugar isotopically-labeled at a single unique position, neutron scattering structure factors and radial distribution functions can be compared with MD simulations constrained to different conformations to determine which conformer best fits the experimental results. Three different simulations were performed with the methyl ether group of the sugar unconstrained and constrained in each of its staggered orientations. The results of the unconstrained simulation showed that the methyl ester group occupied predominantly the 300° position, which is in agreement with the diffraction experimental results. This result suggests that the molecular mechanics force field used in the simulation adequately describes the conformation of the 1-methyl ether group in the methyl β-d-ribofuranoside.

Introduction

The role of ribose and its derivatives in the nucleic acids gives this pentose a singular importance among the monosaccharides. The conformations of RNA are largely controlled by the conformations of its ribose rings and their connecting substituents in aqueous solution. Not surprisingly, the conformations of such molecules have long been a subject of intense interest.1–4 In nucleic acids, the ribose sugars exists as methyl β-d ribofuranosides, with a base bound at position 1 and with phosphate groups at positions 3 and 5 (Figure 1). Understanding the rotational behavior about such linkages in aqueous solution would thus be essential in the understanding of the conformational behavior in the nucleic acids themselves. Unlike the six-atom pyranose sugar rings, which are relatively rigid and do not undergo ring conformational transitions at room temperature, unsubstituted five-atom furanose rings are more flexible, with frequent transitions between various twist and envelope conformers separated by small energy barriers, since the interconversions do not involve transition states with eclipsed 1,2 interactions. However, the complete set of possible conformers separates into two distinct families which are separated by more substantial barriers, inhibiting transitions between the two groupings.5 The presence of large, bulky substituents on a furanose ring can significantly inhibit conformational transitions.

Figure 1.

Right, an illustration of a diphospho-nucleoside derivative of ribose, substituted at the C1 position with a guanine base and with phosphate groups at the C3 and C5 positions, as in RNA. The H3 aliphatic proton, which is the site of H/D substitution in the present experiments, is shown in yellow. Left: The actual methyl-substituted nucleoside of ribose investigated in the present study. In both schematics, the H3 aliphatic proton, representing the site of the H/D substitution in the present work, is shown in yellow.

Recently we reported a way to probe the conformations of flexible solutes in aqueous solution using neutron scattering experiments.6,7 In such solutes, the measured structure factors are dominated by intramolecular correlations and the distances between specific atoms may change with the molecular conformation, which in turn could lead to a detectable change in the structure factors. A variation of the classical technique of neutron diffraction with isotopic substitution (NDIS) experiments,8,9 in which a solute molecule is specifically labeled by isotopic substitution at a single position, allows scattering experiments to probe the intramolecular conformations of the solute. Such experiments, called conformational analysis using neutron diffraction with isotopic substitution (CANDIS), can be used in conjunction with MD simulations of the same systems to probe in detail how solvation and other factors such as temperature affect molecular conformations. Such studies previously have been successfully used to characterize the conformations of exocyclic hydroxyl and hydroxymethyl groups in both d-xylopyranose and d-glucopyranose.6,7,10 Here we report an extension of of this approach to the case of a specifically-labeled, methyl-substituted ribose system.

NDIS experiments8,9 yield a summation of several pairwise radial distribution functions from the substituted nucleus to all other atoms in the system. In the case of multiply-substituted nuclei, particularly in an asymmetric polyatomic solute, the results become more complex and difficult to interpret. However, the availability of singly-substituted sugars makes possible H/D NDIS studies that probe the structure about a single labeled position. In addition to possessing multiple atoms of the same element in different environments, reducing sugars also present other difficulties, since they exhibit complex tautomeric equilibria where multiple forms of the sugar interconvert in solution.11 For glucose this equilibrium is relatively simple, with only the two pyranoid anomers α and β present in significant amounts, in the proportions 36 to 64% respectively, with little of the furanoid and open chain tautomers. However, ribose exhibits a significantly more complex anomeric equilibrium, with significant amounts of both the α and β anomers of both the pyranose and furanose ring forms present, but again with very little of the open chain aldehyde form. The interconversion of these forms can be halted by substituting the hydroxyl group of the anomeric carbon with a methyl group (a methyl glycoside), or a purine or pyramidine base in the case of RNA. It is then possible to isolate both a single ring and anomeric form of the sugar from this mixture. This has the dual advantage of making the system more congenial to study by diffraction methods and simultaneously more biologically relevant to its counterparts in nucleosides and phosphorylated nucleosides (Figure 1).

Methods

Molecular Dynamics

In the MD simulations a neutral periodic cubic system was created at 5 molal concentration containing 36 independent ribose molecules surrounded by explicit water molecules. The simulations employed the newest CHARMM sugar force field12–14 with water molecules being represented by the TIP3P model.15,16 All calculations were performed in an NVT ensemble using the CHARMM program,17,18 with a time step of 1 fs and all chemical bonds to hydrogen atoms kept fixed using SHAKE.19 The starting coordinates were created by placing 36 β ribose (randomly orientated) in a 34 Å cube. These coordinates were superimposed on a box containing 1296 water molecules; those which were within 2.5 Å of any solute heavy atom were discarded in order to produce the correct concentration, a 5 molal solution (36 ribose molecules and 609 TIP3P water molecules, 5.02 molal). Finally the box length was rescaled to 30.686 Å, yielding the correct physical number density (0.107 atoms Å−3).

The van der Waals and electrostatic interactions were smoothly truncated on a group basis using switching functions from 13 to 15 Å. Initial velocities were assigned from a Boltzmann distribution (300 K) followed by 7 ps of equilibration dynamics with velocities being reassigned every 0.1 ps. The simulations were subsequently run for 10 ns with no further velocity reassignment. The first 2 ns of this were taken as equilibration, and the remaining 8 ns were used for analysis. Three further simulations were performed with the exocyclic alpha methyl ether conformational angle O5-C1-O1-CME constrained to the values of either 60°, 180°, or 300° (Figure 2). In each case the thermalized final coordinates of the free simulation were used and the simulation was run for 2 ns.

Figure 2.

The three constrained positions of the methyl ether group in the ribose examined in this study. In each case the substituted nucleus (H3) is shown in yellow. Other nuclei are color coded according to the sign of their scattering length and are of a size proportional to their scattering length. O (5.81 fm) and C (6.64 fm) are both positive (purple), Hnon (−3.74 fm) is negative and shown in green. The exchangeable hydrogens are colored grey as their neutron scattering length depends on the isotopic composition of the water (6.67 fm in D2O and −3.74 fm in H2O).

Experimental

Methyl β-d-ribofuranoside substituted only on position H3 (Figure 1), methyl β-d-d3 ribofuranoside, was purchased from Omicron, while natural-abundance methyl β-d-ribofuranoside was obtained from Sigma. The same sugar samples were used for preparing the H2O and D2O solutions. The method used for preparing both sugar solutions was as follows: to 0.6 g (accurately measured in each case) of ribose, the appropriate amount of light water to make a 5 molal solution (ca 0.6 ml) was added gravimetrically. After 8 hrs of neutron scattering data was collected for this sample, the entire sample was quantatively transferred, using D2O washings, to a 25 ml pear flask of known mass, and the solvent was removed on a rotary evaporator using a Teflon headed pump in a water bath at ca 50°C. After the water had effectively stopped coming off, the flask was removed and weighted to assess the fraction of water that had been removed (typically >95%). A further 4 ml of D2O was then added and the process was repeated. In total this process was conducted 6 times, after which the correct amount of D2O was added gravimetrically to the room temperature flask. Four hours of neutron scattering data were then collected on the D2O sample. This procedure was repeated for both the natural abundance and isotopically labeled ribose samples.

Description of the Method

The first order difference method is well documented in the literature, and uses the assumption that solutions of identical chemical constitution, but with different isotopic concentrations of a probe nucleus are structurally equivalent around the probe nucleus.8,9 The directly measured difference function (Δ(Q)) can be fourier transformed to a real space representation of the data (G(r)) which contains structural correlations of the substituted nucleus to other atoms in the system. This data is composed a series of radial distribution functions weighted by prefactors, which are calculated from the atomic composition of the system, and the neutron scattering lengths of those components. Here we apply this method first to d3-substituted/natural abundance ribofuranose in D2O, and second, to d3 substituted/natural abundance ribofuranose in H2O. In both cases the ratio of ribofuranose to water was 5:55.55, referred to here as 5 molal. These first order difference experiments yield the following difference functions

where H3 is the substituted non-exchangeable hydrogen, and Hex represents all the exchangeable hydrogen in the system (i.e. the hydrogen atoms on water and the hydrogen atoms on the hydroxyl groups). The Fourier transform of these functions allows a real space representation to be obtained of the same data,

Clearly D2OΔHsub(Q)-H2OΔHsub(Q) yields 17.2 SH3Hex(Q). Furthermore, the isolated SH3Hex(Q) component can be subtracted from to yield

which can in turn be Fourier transformed to yield

Results and Discussion

The raw first order differences , and 17.2 SH3Hex(Q) before and after subtraction of the Placzek correction20,21 are shown in Figure 3–5, respectively.

Figure 3.

The raw first order differences (black), (red) and the function 17.2 SH3Hex(Q) (blue). Also shown in magenta is the spline used in the analysis of the 17.2 SH3Hex(Q) data.

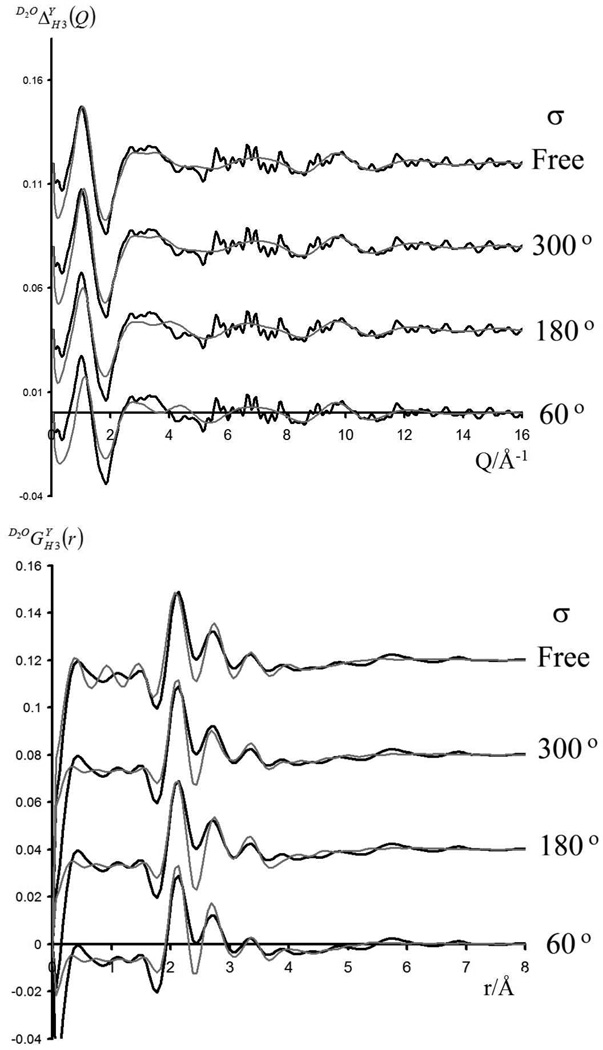

Figure 5.

In each case the experimental data is shown in black and the MD simulated data in grey. Lower is shown the real space function , while upper is shown the reciprocal space function for each of the MD simulations and experimental data. The upper plot is the data after all component corresponding to r space features lower than 1.7 Å have been removed (set to zero). Lower is the real space representation of this data after the experimental resolution has been applied to the MD data (setting Q values > 16 Å−1 to zero).

Using the MD simulations, the experimentally determined structure factors were calculated for the free simulation, and for simulations in which the O5-C1-O1-CM dihedral angle was constrained to 60°, 180° and 300° respectively (see Figures 4–6). In the free simulation the methyl ether groups occupy the 300° and 180° positions with populations of 90 and 10%, respectively. For the 60°, 180° and 300° simulations, the average distance from the substituted nucleus (H3) to the carbon of the methyl ether group (CM) was 2.8, 3.7 and 4.9 Å, respectively. When the methyl-ether group occupies a certain position, it excludes water from that volume. To a first approximation, the methyl group and a water molecule are of comparable size (both capable of being represented as a single extended atom); however, in the D2O case, this volume contains 3 nuclei with a total scattering length of 19 fm (scattering length of D = 6.67 fm, that of O = 5.81 fm) while in the methyl case the total scattering length of the methyl group is −4.6 fm (H = −3.74 fm, C = 6.65 fm). So, to a first order approximation, there are two principal effects involved: the methyl occupying a position, and the methyl group excluding water. This has to be considered knowing that this effect will produce bigger apparent changes in the real space function when these changes happen at low r (e.g. for the 60° position) than at higher r (e.g. the 300° position) due to the r2 factor inherent in these functions in relating the effectively identical change in scattering length density to the size of the signal observed in the real space function. This will obviously have different effects in the functions and , as the average scattering length of the 'excluded' water changes from 19 fm for D2O to −1.7 fm for H2O. It is this contrast, combined with the fact that the distance between the substituted H3 nucleus and the methyl ether groups varies significantly with the O5-C1-O1-CM dihedral, that renders both the experimentally determined functions / and 17.2 SH3Hex(Q)/17.2 gH3Hex(r) primarily sensitive to the conformation of the methyl ether group. For while there are other degrees of freedom in this system, most notably the conformation of the OH groups on C2 and C3, and the hydroxylmethyl group, they do not produce the large movement of high contrast groups of nuclei. This can be visually seen in Figure 2, where the nuclei are colored and sized approximately according to scattering length (C ~ O ~ D ~6 fm, while H ~ −3 fm).

Figure 4.

In each plot the experimental data are shown in black and the MD simulated data in grey. In each case the lower line represents the function , the middle line and the upper line 17.2 SH3Hex(Q). In each case, the Placzek slope has been removed from the experimental results by Fourier filtering the data and by eliminating all real space correlations corresponding to r < 0.5 Å).

Figure 6.

In each case the experimental data is shown in black and the MD simulated data in grey. Lower are shown the real space function 17.2 gH3Hex(r), while upper are shown the reciprocal space function 17.2 SH3Hex(Q) for each of the MD simulations and experimental data. For the experimental data, lower is shown the direct fourier transform of the splined data shown in Figure 5. For the MD data the data is first back transformed to yield 17.2 SH3Hex(Q). The MD data then has the experimental resolution applied to it (setting Q values > 16 Å−1 to zero) prior to fourier transforming the data to yield the lower function 17.2 gH3Hex(r).

In order to assess which conformation of the O5-C1-O1-CM dihedral best fits the experimental data, it is necessary to consider all the experimentally determined structure factors. However, the first order differences and are convoluted with the function 17.2 SH3Hex(Q). Figure 6 shows the functions (note = ) after the deconvolution of the SH3Hex(Q) component of each function. These considerably enhanced functions permit the determination of which of the constrained simulations best fits the experimental data; it should be noted that the function SH3Hex(Q) is sensitive to the exclusion of water by the methyl ether group, but does not contain any signal from the nuclei of the methyl ether group itself. Conversely the function contains correlations from the methyl ether group, but a diminished contrast due to the exclusion of water, given that this function contains no correlations to the exchangeable hydrogens. However, while the function is most consistent with the 300° position in both real and reciprocal space, arguably the function SH3Hex(Q) is most consistent with the 180° position, but taken together, the 300° position provides a better approximation to the experimental data.

In order to assess which set of simulation data was the best fit to the experiment, the squared difference was taken between the two data sets, which was then multiplied by r2 to make the comparison proportional to the number of atoms, and then summed in the region 2–5 Å. This procedure yielded values of 0.091, 0.051, 0.046, and 0.047 for the 60°, 180°, 300°, and free simulations, respectively. This shows that the experimental data is least consistent with the 60° simulation, and that while the 180° and 300° simulations and the unconstrained simulations provide comparable fits to the experimental data, the 300° simulation is the slightly better fit.

Conclusions

Neutron diffraction experiments are a potentially very powerful means of probing the structure of aqueous solutions. The measured structure factors in principle contain information about the correlation of every type of atom in the solution with every other type of atom. In the case of a complex asymmetric biological solute like a sugar, however, the very complexity of this information-rich measurement makes it almost impossible to interpret. Studies with single atomic substitutions, such as repoted here, in principle allow some of the information contained in the neutron scattering measurements to be usefully deconvoluted when compared with MD simulations of the same system. While quite difficult, this CANDIS approach demonstrates how neutron scattering experiments might be employed in the future to probe the conformations of flexible biomolecules in aqueous solution.

In the present application, the MD simulations of the free methyl β-d-ribofuranoside show that the methyl ether on C1 (where the base pair would usually be located in RNA) occupies mostly the 300° orientation. The NDIS results, which are sensitive to the orientation of the methyl ether due both to the change in the neutron scattering density as a function of methyl ether position itself (mostly through ), and to the displacement of water by the methyl ether (SH3Hex(Q)), are most consistent with the simulated data with the methyl ether in the 300° orientation, and least consistent with the 60° conformation. The simulation with this group constrained to the 180° conformation fit the experimental data almost as well, but the 60° conformation can be ruled out using this approach. The conformation at 300° was also the most populated form (~90%) in the unconstrained simulation, further supporting this conformer as the experimental structure. In the present case, this information could be obtained by other, simpler means, such as NMR. The present results demonstrate, however, that this type of approach could be used, particularly as detectors become more sensitive and stable and neutron beams become more intense and stable, to supplement other techniques in the study of aqueous solutions.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Henry Fischer of the Institut Laue-Langevin. This project was supported by grant GM63018 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Olson WK. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1982;104:278–286. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey SC, Prabhakaran M. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1986;108:6128–6136. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prabhakaran M, Harvey SC. Biopolymers. 1988;27:1239–1248. doi: 10.1002/bip.360270805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Eijck BP, Kroon J. Journal of Molecular Structure. 1989;195:133–146. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoddart JF. Stereochemistry of Carbohydrates. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1971. p. 249. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason PE, Neilson GW, Enderby JE, Saboungi M-L, Brady JW. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2006;110(7):2981–2983. doi: 10.1021/jp055658j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mason PE, Neilson GW, Enderby JE, Saboungi M-L, Cuello G, Brady JW. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2006;125 doi: 10.1063/1.2393237. 224505 (nine pages). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enderby JE. Chemical Society Reviews. 1995;24(3):159–168. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neilson GW, Enderby JE. Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1996;100:1317–1322. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mason PE, Neilson GW, Enderby JE, Saboungi M-L, Brady JW. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127(31):10991–10998. doi: 10.1021/ja051376l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shallenberger RS. Advanced Sugar Chemistry: Principles of Sugar Stereochemistry. Westport, Connecticut: AVI Publishing Company, Inc.; 1982. p. 323. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foloppe N, MacKerell AD. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2000;21:86–104. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foloppe N, Nilsson L, MacKerell AD., Jr. Biopolymers (Nucleic Acid Sciences) 2002;61:61–76. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)61:1<61::AID-BIP10047>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guvench O, Greene SN, Kamath G, Brady JW, Venable RM, Pastor RW, Mackerell AD. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2008;29:2543–2564. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1983;79(2):926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durell SR, Brooks BR, Ben-Naim A. Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1994;98:2198–2202. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 1983;4(2):187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brooks BR, Brooks CL, A.D. MacKerell J, Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartels C, Boresch S, Caflisch A, Caves L, Cui Q, Dinner AR, Feig M, Fischer S, Gao J, Hodoscek M, Im W, Kuczera K, Lazaridis T, Ma J, Ovchinnikov V, Paci E, Pastor RW, Post CB, Pu JZ, Schaefer M, Tidor B, Venable RM, Woodcock HL, Wu X, Yang W, York DM, Karplus M. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2009;30(10):1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Gunsteren WF, Berendsen HJC. Molecular Physics. 1977;34(5):1311–1327. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mason PE, Ansell S, Neilson GW. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 2006;18(37):8437–8447. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/18/37/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason PE, Neilson GW, Dempsey CE, Brady JW. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:15136–15144. doi: 10.1021/ja0613207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]