Abstract

Background

Corylus was renowned for its production of hazelnut and taxol. To understand the local adaptation of Chinese species and speed up breeding efforts in China, we analyzed the leaf transcriptome of Corylus mandshurica, which had a high tolerance to fungal infections and cold.

Results

A total of 12,255,030 clean pair-end reads were generated and then assembled into 37,846 Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) sequences. During functional annotation, 26,565 ESTs were annotated with Gene Ontology (GO) terms using Blast2go and 11,056 ESTs were grouped into the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways using KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS). We identified 45 ESTs that were homologous to enzymes and transcription factors responsible for taxol synthesis. The most differentiated orthologs between C. mandshurica and a European congener, C. avellana, were enriched in stress tolerance to fungal resistance and cold.

Conclusions

In this study, we detected a set of genes related to taxol synthesis in a taxol-producing angiosperm species for the first time and found a close relationship between most differentiated genes and different adaptations to fungal infection and cold in C. mandshurica and C. avellana. These findings provided tools to improve our understanding of local adaptation, genetic breeding and taxol production in hazelnut.

Keywords: Corylus mandshurica, Transcriptome, Adaptation, Divergence, Fungi/fungus, Cold/frigid, Taxol/paclitaxel

Background

Corylus is an important genus, both economically and ecologically, in China. There is currently more than 4 million acres of natural hazel groves in northeastern China alone [1]. Its nuts, rich in unsaturated fat and vitamins, are widely consumed. Its leaves are used by local farmers to feed domestic silkworm [2]. Its stocks have been successfully used for grafting Castanea henryi to improve chestnut production and quality [3] and have also been shown to be an ideal substitute for logs of Carpinus cordata in Ganoderma culture [4]. A part from its clear economic importance, Corylus plays an important role in soil and water conservation owing to its strong root system and contributes to the sustainability of forests in this region [2].

Corylus species are also important sources of taxol (also named as Paclitaxel), which is an effective yet relatively expensive medicine for treatment of breast, ovarian and lung cancer [5-7]. Taxol was originally isolated from the bark of Pacific yew [8] and then later found to be present in the yew genus Taxus[9]. It was initially believed to occur only in gymnosperms, but was recently identified in leaves and fruits of a hazelnut species (C. avellana) [10]. Further studies validated this finding by showing that in vitro hazel cell cultures produce taxol and taxanes, indicating that it is not exclusively produced by symbiotic fungi [11-13]. Taxol was recently discovered in another hazelnut species, C. mandshurica (synonym to C. sieboldiana) [14]. However, except for the Corylus species as well as a few other species like Magujreothamnus speciosus, Morinda citrifolia, Justicia gendarussa and Yunnanopilia longistaminata[15,16], few angiosperm species have been reported to contain taxol or its derivatives. Interests in taxol production from hazel trees, especially from its leaves, have grown rapidly with the aim of conserving endangered yew species [17].

C. mandshurica is widely distributed in northeastern China and its nuts are characterized by a thin husk and high shelling percentage [18]. The nuts from this species are of higher quality in flavor and taste, and therefore command a higher price than the nuts from C. avellana. Moreover, C. mandshurica is highly resistant to Eastern Filbert Blight [19], a fungus that causes seriously damage to most commercially grown cultivars of C. avellana in the US [20], and has exceptional cold resistance; it is able to survive a frigid winter of -48°C [21,22]. All these traits make it a very desirable target for developing improved selections and breeding material [18,23]. Interspecific crossing and breeding experiments have been attempted between C. mandshurica and the commercial species C. avellana[1,22-26]. Molecular breeding aided by microsatellite marking has also been reported [27,28].

Next generation sequencing is a quick and cost-effective method for surveying the complete coding sequence of a genome. Much progress has been made in obtaining longer sequence reads, and many tools and algorithms have been developed to allow assembly of short reads. Despite the ever-increasing sequencing data, the Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs) from C. avellana have only recently been released [29] and remain the only available large-scale sequencing data for the Corylus genus. In this study, we sequenced the leaf transcriptome of C. mandshurica native to China. Our aims were (1) to explore how homologous genes of two hazel species have differentiated to give their contrasting adaptations, and (2) to identify the possible genetic basis of taxol production in the genus Corylus by transcriptome assembly and gene annotation.

Results and discussion

Sequencing and assembly

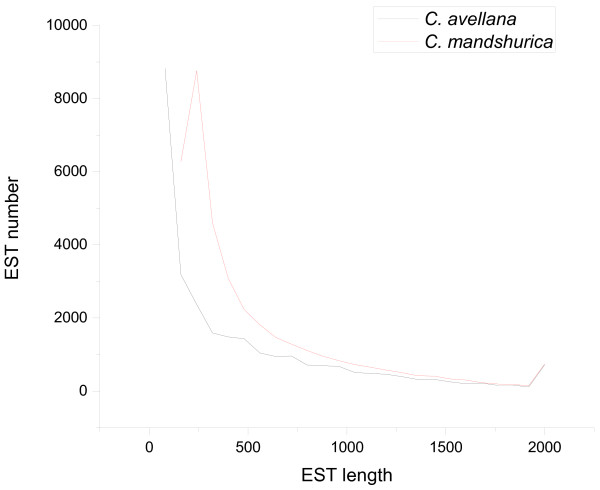

After strict quality control, 12,255,030 clean pair-end reads were assembled into 37, 846 ESTs longer than 200 bp using Trinity [30]. The contig N50 was 799 bp and 8,328 ESTs had longer sequences. A total of 37,652 coding DNA sequences (CDSs) were predicted to have an average length of 431 bp using Orfpredictor [31]. Comparison of our assembly with the Jefferson transcriptome assembly on C. avellana was shown in Table 1. It could be seen that the contig N50 of our assembly was slightly lower, which was partly due to the large increase in the number of assembled sequences. It was apparent from EST length distribution (Figure 1) that our assembly had more sequences at all length intervals beyond 160 bp. The assembled EST sequences of C. mandshurica in fasta format were available in Additional file 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of transcriptome assembly and coding sequence prediction for Corylus mandshurica and Corylus avellana

|

EST |

CDS |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. mandshurica | C. avellana | C. mandshurica | C. avellana | |

| Average Length |

580 |

532 |

431 |

377 |

| Length Range |

201 ~ 6821 |

80 ~ 5490 |

30 ~ 4890 |

42 ~ 4143 |

| Numbers |

37846 |

28255 |

37652 |

28167 |

| N50 Length |

799 |

961 |

594 |

651 |

| Sequences (longer than N50) | 8328 | 4991 | 8028 | 4945 |

Figure 1.

The length distribution of assembled ESTs from transcriptomes of C. mandshurica and C. avellana. ESTs are counted at an interval of 80 bp, with ESTs longer than 2000 bp counted as 2000 bp. It is clear that more ESTs are assembled in the transcriptome of C. mandshurica than C. avellana at length intervals after 160 bp. (Trinity has a minimum length of 200 bp in transcriptome assembly).

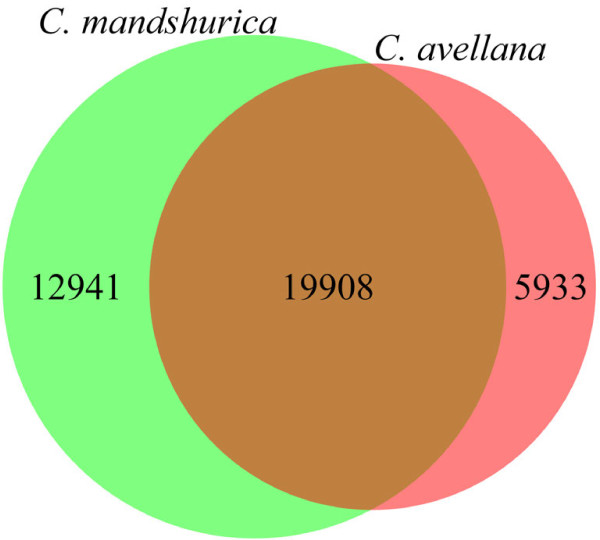

Given the recently released genome of Betula nana[32], we used BLAT [33] to map our transcriptome assembly against this genome that currently consisted of 551,915 contigs. We found that 32,078 ESTs mapped to 32,849 contigs. In comparison, 25,073 ESTs out of the Jefferson transcriptome assembly mapped to 25,841 contigs, with 19,908 contigs shared between the two hazelnut transcriptome assemblies (Figure 2). The ESTs that mapped to unique contigs might represent different genes specifically expressed in each species or different fragments of the same genes due to the fragmentary nature of the current Betula genome and the limited sequencing depth of the transcriptomes. Thus, our transcriptome analysis revealed many novel EST sequences for the Corylus genus that could not be identified from the Jefferson transcriptome assembly and helped locate the genomic locus for each EST, which had important implications for the development of further breeding markers of the Corylus species.

Figure 2.

The contigs from Betula nana genome mapped by transcriptomes of C. mandshurica and C. avellana. The contigs mapped uniquely by ESTs from C. mandshurica may represent novel genes specifically expressed in it or different fragments of the same genes unidentified in the transcriptome of C. avellana.

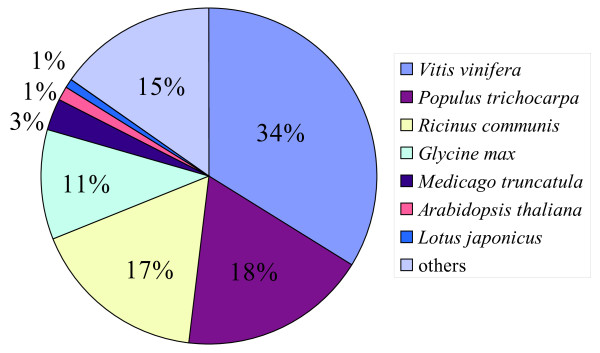

Functional annotation

To functionally classify the assembled ESTs, a homology-based approach was adopted in transcriptome annotation. A total of 30,536 ESTs gave hits on performing BLASTX searches [34] in the NCBI non-redundant protein database using an E-value cutoff of 1e-5, accounting for 80.7% of all assembled sequences. When sorting the top blast hits by species, Vitis vinifera was ranked first with 10,321 top blast hits, followed by Populus trichocarpa and Ricinus communis with 5,537 and 5,155 top blast hits, respectively (Figure 3). In addition, 26,565 ESTs were annotated with Gene Ontology (GO) terms using Blast2go [35] and 11,056 ESTs were annotated into Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways with KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS) [36] using the Single-directional Best Hit (SBH) method.

Figure 3.

The percentage of top blast hits by species.

Identification of highly differentiated genes in the transcriptomes of C. mandshurica and C. avellana

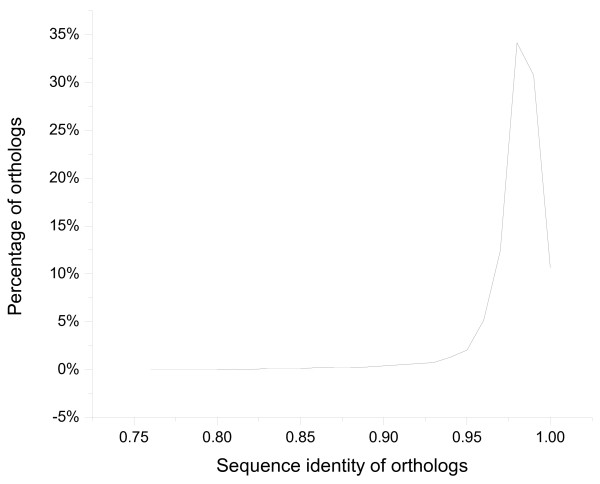

Since C. mandshurica and C. avellana were closely related species but with contrasting adaptations, our first goal was to identify which genes were highly differentiated. Using the available EST sequences for these two species, we performed a reciprocal blast to obtain best hit orthologs and compared both the sequence identities and presence of Insertion/Deletion (INDEL) according to BLASTN outputs. Since 98.7% of orthologs showed a sequence identity higher than 90% (Figure 4), we set a sequence identity of 90% as the low threshold in ortholog validation to exclude the presence of distantly related homologs. Because we were interested in orthologs with relatively great divergence between C. mandshurica and C. avellana, we took orthologs with the low sequence identity (less than 97%), which account for 10.4% of all orthologs, as the highly differentiated genes. Furthermore, INDEL might cause different reading frames in coding regions of the two sets of orthologous ESTs [37]. It might also cause mRNA secondary structure change [38] in the coding and noncoding regions with alternative roles in transcriptional polyadenylation site selection [39], pre-mRNA splicing [40], mRNA stability, translation efficiency and protein folding [41,42]. Therefore, INDEL was also used as an indicator for sequence divergence. Thus, orthologs with gaps in the BLAST alignment were taken as another set of highly differentiated genes. Next, we performed separate GO enrichment analyses on these two types of differentiated orthologs using the WEGO web server [43]. GO terms for all orthologs and the two types of highly differentiated orthologs were available in Additional files 2, 3, 4).

Figure 4.

The distribution of sequence identity in blast regions for all orthologs. 98.7% orthologs have sequence identity no less than 90%; 87.9% orthologs have sequence identity no less than 97%. To exclude distantly homologous sequences, orthologs with sequence identity less than 90% are discarded in GO enrichment analysis.

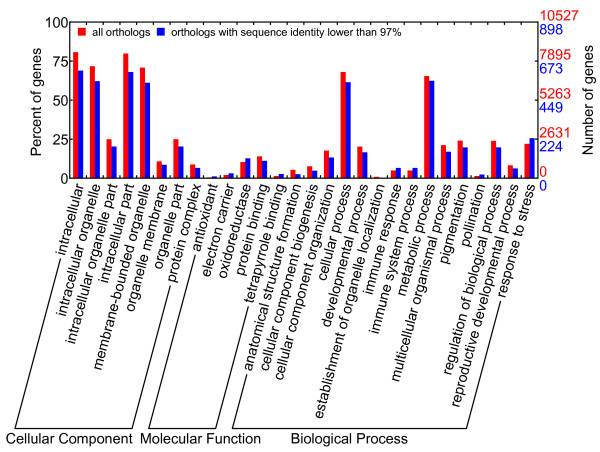

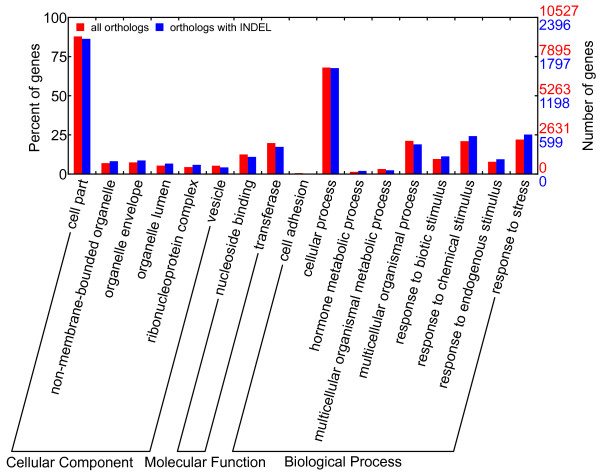

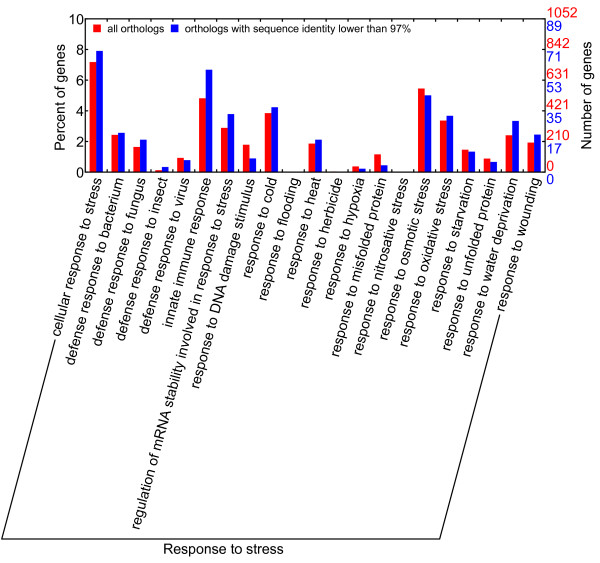

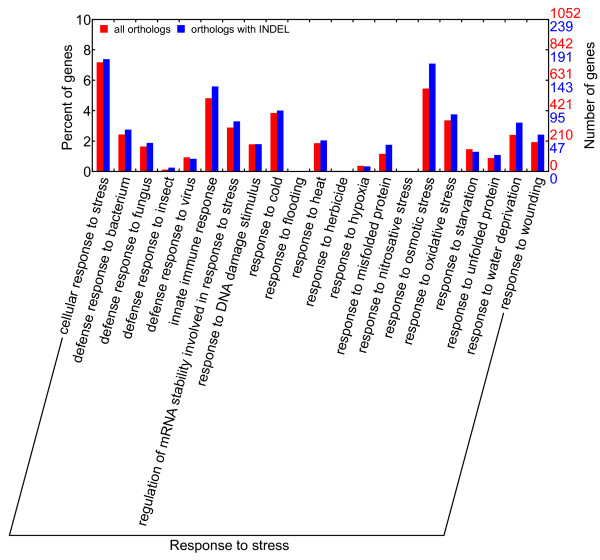

According to the GO enrichment analyses (Figures 5 and 6), orthologs from most statistically significant GO terms were conserved in the respective sequences as they generally contained a low percentage of orthologs with a sequence identity lower than 97% or orthologs with INDEL. The conserved GO categories comprised GO terms in cellular process, developmental process and metabolic process (except hormone metabolic process) in the biological process domain for both species. All these processes were essential for plant survival. The divergent GO categories comprised immune, pollination and response to stress in the biological process domain for the GO enrichment of orthologs with sequence identities lower than 97%. The orthologs with INDEL were enriched in hormone-related or various stimuli-related GO terms in the biological process domain (including hormone metabolic process and responses to various stimuli, especially response to stress). These findings suggested that C. mandshurica and C. avellana had become genetically differentiated whilst adapting to their different habitats. Stress response genes were more prone to both sequence substitution and insertion/deletion, with occurrences of 25.6% and 25.2% among all differentiated ESTs, respectively. A close examination of GO terms under response to stress (Figures 7 and 8) revealed that three main categories displayed increased sequence divergence, including genes participated in defenses to bacteria and fungi, genes involved in cold tolerance and genes related to salt/drought/water stress. As C. mandshurica has better adapted to fungal infection and cold stress than C. avellana, further study of the highly divergent genes in C. mandshurica could identify the key genes responsible for the resistance to fungal infection and cold pressure. However, because orthologs were not necessarily one to one match between two species when gene duplication occurred after speciation, the identified orthologs could be either true alleles or different copies of the same family in the genomes. Under the latter scenario, differential expressions of the genes at both time and space should be carefully examined, which might also represent one of the adaptation mechanisms in this species.

Figure 5.

GO enrichment on orthologs with sequence identity lower than 97%. Direct parent GO terms in biological process domain are displayed for simplicity. The GO terms in the biological process domain that show increase in ESTs with lower sequence identity are related to immune response and response to stress.

Figure 6.

GO enrichment on orthologs with INDEL. Direct parent GO terms in biological process domain are displayed for simplicity. The GO terms in the biological process domain that show increase in ESTs with INDEL are related to hormone metabolic process and response to various stimuli (including response to stress).

Figure 7.

GO terms under response to stress in GO enrichment on orthologs with low sequence identity. GO terms related to defense against bacteria and fungi (including innate immune response), tolerance to cold and heat, and salt/drought/water stress show increase in ESTs with lower sequence identity.

Figure 8.

GO terms under response to stress in GO enrichment on orthologs with INDEL. GO terms related to defense against bacteria and fungi (including innate immune response), tolerance to cold and heat, and salt/drought/water stress show increase in ESTs with INDEL.

Genes responsible for taxol synthesis

According to KEGG annotation, 29 ESTs were found to be involved in the terpene synthesis pathway. These included genes involved in isopentenyl-PP (IPP) synthesis in both the mevalonate and MEP/DOXP pathways and genes responsible for geranyl-PP and geranyl-geranyl-PP (GGPP) synthesis. The committing step for taxol production was the conversion of GGPP to taxa-4(5)-11(12)-diene in the diterpenoid biosynthesis pathway; however, genes involved in this reaction, as well as the following processes, were absent from our KEGG annotation. This was also encountered in the KEGG annotation of C. avellana transcriptome. Nonetheless, 31 ESTs (Table 2) were found to be homologous to the prototype genes participating in taxol synthesis in yew species, with sequence identities ranging from 23.93% to 50.32%. This was similar to the sequence identities of 40% ~ 44.1% reported in some taxol-producing fungi [44] and was close to the maximal sequence identity of around 40% ~ 49.3% found between these genes and the available proteins from other plant species in the NCBI non redundant protein database (Table 3). In addition, 6 ESTs were found to be homologous to WRKY, and 8 ESTs homologous to JAMYC. These two transcriptional factors had been reported to induce taxol synthesis [45,46].

Table 2.

ESTs homologous to genes involved in taxol synthesis in Taxus

| EST ID | Hit Protein GI | Identity (%) | Length | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| comp37211_c1_seq1 |

386304248 |

36.51 |

189 |

10-deacetylbaccatin III-10-O-acetyl transferase, partial |

| comp42386_c0_seq1 |

28558088 |

28.85 |

104 |

3′-N-debenzoyl-2′-deoxytaxol N-benzoyltransferase |

| comp70594_c0_seq1 |

339521621 |

23.93 |

422 |

C-13 phenylpropanoid side chain CoA acyltransferase |

| comp70669_c0_seq1 |

28380187 |

34.95 |

432 |

taxa-4(20),11(12)-dien-5alpha-ol-O-acetyltransferase |

| comp68118_c0_seq1 |

28380187 |

28.44 |

450 |

taxa-4(20),11(12)-dien-5alpha-ol-O-acetyltransferase |

| comp53308_c0_seq1 |

386304662 |

38.04 |

163 |

taxadienol acetyl transferase, partial |

| comp119236_c0_seq1 |

53690152 |

45.98 |

87 |

taxadien-5-alpha-ol-O-acetyltransferase |

| comp68580_c0_seq1 |

53690152 |

30.06 |

173 |

taxadien-5-alpha-ol-O-acetyltransferase |

| comp37211_c0_seq1 |

53690152 |

32.39 |

142 |

taxadien-5-alpha-ol-O-acetyltransferase |

| comp83331_c0_seq1 |

53690152 |

28.84 |

215 |

taxadien-5-alpha-ol-O-acetyltransferase |

| comp64789_c0_seq1 |

53759170 |

42.6 |

446 |

taxadiene 5-alpha hydroxylase |

| comp57975_c0_seq1 |

386304485 |

50.32 |

155 |

taxadiene 5nalpha hydroxylase, partial |

| comp172528_c0_seq1 |

38201489 |

36.47 |

85 |

taxa-4(5),11(12)-diene synthase |

| comp193967_c0_seq1 |

15080743 |

46.03 |

63 |

taxadiene synthase |

| comp63152_c1_seq1 |

386304920 |

29.69 |

128 |

taxadiene synthase, partial |

| comp40035_c0_seq1 |

24266823 |

47.89 |

71 |

5-alpha-taxadienol-10-beta-hydroxylase |

| comp53405_c1_seq1 |

24266823 |

49.47 |

95 |

5-alpha-taxadienol-10-beta-hydroxylase |

| comp133851_c0_seq1 |

44903417 |

32.47 |

77 |

5-alpha-taxadienol-10-beta-hydroxylase |

| comp110423_c0_seq1 |

60459952 |

41.38 |

87 |

taxane 13-alpha-hydroxylase |

| comp69534_c0_seq1 |

60459952 |

33.79 |

441 |

taxane 13-alpha-hydroxylase |

| comp38773_c1_seq1 |

60459952 |

45.83 |

96 |

taxane 13-alpha-hydroxylase |

| comp36415_c0_seq1 |

60459952 |

34.19 |

427 |

taxane 13-alpha-hydroxylase |

| comp57975_c1_seq1 |

60459952 |

44.93 |

69 |

taxane 13-alpha-hydroxylase |

| comp104139_c0_seq1 |

60459952 |

42.17 |

83 |

taxane 13-alpha-hydroxylase |

| comp93979_c0_seq1 |

75297723 |

38.03 |

71 |

Taxane 14b-hydroxylase |

| comp61533_c1_seq1 |

380039801 |

33.57 |

143 |

taxane 14b-hydroxylase |

| comp143394_c0_seq1 |

380039801 |

29.17 |

120 |

taxane 14b-hydroxylase |

| comp74596_c0_seq1 |

380039801 |

29.51 |

122 |

taxane 14b-hydroxylase |

| comp84707_c0_seq1 |

380039801 |

35.22 |

230 |

taxane 14b-hydroxylase |

| comp36896_c0_seq1 |

67633430 |

30.84 |

467 |

taxoid 2-alpha-hydroxylase |

| comp192945_c0_seq1 |

238915468 |

43.75 |

64 |

taxoid 7-beta-hydroxylase |

| comp36946_c0_seq1 |

365776087 |

55 |

60 |

transcription factor WRKY |

| comp64330_c0_seq1 |

365776087 |

54.24 |

59 |

transcription factor WRKY |

| comp78449_c0_seq1 |

365776087 |

66.67 |

54 |

transcription factor WRKY |

| comp67132_c0_seq1 |

365776087 |

56.34 |

71 |

transcription factor WRKY |

| comp59687_c0_seq1 |

365776087 |

41.22 |

131 |

transcription factor WRKY |

| comp68275_c0_seq1 |

365776087 |

56.72 |

67 |

transcription factor WRKY |

| comp104123_c0_seq1 |

222355764 |

29.87 |

154 |

JAMYC |

| comp69212_c0_seq1 |

222355764 |

41.69 |

710 |

JAMYC |

| comp69212_c0_seq2 |

222355764 |

46.72 |

259 |

JAMYC |

| comp69212_c0_seq3 |

222355764 |

41.69 |

710 |

JAMYC |

| comp124731_c0_seq1 |

222355764 |

100 |

27 |

JAMYC |

| comp69971_c3_seq1 |

222355764 |

29.9 |

204 |

JAMYC |

| comp38183_c0_seq2 |

222355764 |

30 |

160 |

JAMYC |

| comp83061_c0_seq1 | 222355764 | 35.71 | 112 | JAMYC |

Protein GIs, instead of their accession numbers, are provided here for convenience in table layout. These can be queried at NCBI protein databases.

Table 3.

Proteins most homologous to genes involved in taxol synthesis in species outside Taxus

| Query Protein GI | Hit Protein GI | Identity (%) | Taxonomy | Hit Protein GI | Identity (%) | Taxonomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15080743 |

- |

- |

- |

62511183 |

48.53 |

Abies grandis |

| 38201489 |

- |

- |

- |

62511183 |

48.66 |

Abies grandis |

| 386304920 |

- |

- |

- |

62511183 |

49.3 |

Abies grandis |

| 24266823 |

56609042 |

97.99 |

Ozonium sp. BT2 |

75319884 |

43.97 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 44903417 |

56609042 |

99.2 |

Ozonium sp. BT2 |

75319884 |

44.17 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 53759170 |

56609042 |

66.38 |

Ozonium sp. BT2 |

75319884 |

44.44 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 60459952 |

56609042 |

63.9 |

Ozonium sp. BT2 |

75319884 |

45.32 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 67633430 |

56609042 |

56.34 |

Ozonium sp. BT2 |

75319884 |

40.89 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 75297723 |

56609042 |

60.72 |

Ozonium sp. BT2 |

75319884 |

42.5 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 238915468 |

56609042 |

56.2 |

Ozonium sp. BT2 |

75319884 |

40 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 380039801 |

56609042 |

61.12 |

Ozonium sp. BT2 |

75319884 |

42.92 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 386304485 |

56609042 |

66.22 |

Ozonium sp. BT2 |

75319884 |

47.11 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 28380187 |

62461771 |

98.39 |

fungal sp. BT2* |

148906373 |

43.98 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 28558088 |

62461771 |

60.23 |

fungal sp. BT2 |

148906373 |

45.62 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 53690152 |

62461771 |

60.83 |

fungal sp. BT2 |

148906373 |

44.25 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 339521621 |

62461771 |

60 |

fungal sp. BT2 |

148906373 |

39.83 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 386304662 |

62461771 |

98.23 |

fungal sp. BT2 |

148906373 |

44.07 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 386304248 |

169135276 |

98.45 |

Cladosporium cladosporioides |

148906373 |

44.64 |

Picea sitchensis |

| 365776087 |

- |

- |

- |

167859869 |

43.18 |

Picea abies |

| 222355764 | - | - | - | 148906957 | 46.99 | Picea sitchensis |

* Ozonium sp. BT2 and fungal sp. BT2 are the same fungus species. [49,51].

Columns 2-4 show top hit protein information from fungi; columns 5-7 show top hit protein information from plants. Methodically, protein queries are blasted against NCBI nonredundant protein database and protein hits from the two designated sources with top sequence identity are recorded. Protein GIs, instead of their accession numbers, are provided here for convenience in table layout. These can be queried at NCBI protein databases. The reason for only three identified hit proteins from fungi is possibly due to the absence of genome data for taxol-producing fungi.

Overall, our study reported for the first time large-scale identification of genes involved in the terpenoid pathway in Corylus, which would facilitate understanding of taxol synthesis in angiosperms, although further experiments were required to clarify the roles of these genes in such processes. On the other hand, it should be noted that not all sequences of the genes related to taxol synthesis were revealed by the present transcriptome analyses because of difficulties in normalizing all cDNAs before sequencing when the level of leaf mRNA expression in the taxol synthesis pathway was very low. In addition, some taxadiene synthase genes might only be expressed in response to external stimuli, such as naturally occurring fungal infection or artificial chemical induction [47]. Such genes would not be detected by the present approach. Since the family of terpene synthases were highly diversified across plants [48], it would be interesting to investigate the reasons why taxol production was shared by these special gymnosperm and angiosperm plants. Horizontal gene transfer was a likely cause of such convergent evolutions via symbiotic organisms. For example, three genes from different taxol-producing fungi (two from Ozonium sp. BT2 and one from Cladosporium cladosporioides) isolated from the inner tree barks [49-51] had been shown high sequence identities (98.39%, 98.45% and 99.2%) to the corresponding taxol genes in yew species (Table 3). Undoubtedly, these unsolved questions merited further study, especially from genomic scanning and experimental tests.

Conclusions

In the present study, the transcriptome of C. mandshurica was de novo assembled with Trinity and functionally annotated with Blast2go and KAAS. We found that highly differentiated genes between C. mandshurica and C. avellana correlated with local adaptation of the two species. In addition, a set of genes that might contribute to taxol production were identified and genetic mechanisms for taxol synthesis in distantly related plants were discussed. Thus, our study broadened the available transcriptome resources for Corylus, and provided meaningful information for researchers interested in taxol synthesis and high tolerance of C. mandshurica to fungal infection and cold stress.

Methods

Sequencing and assembly

Total RNA was extracted from leaves of C. mandshurica according to the CTAB protocol. The integrity of RNA was detected on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. The initial 20 μg of total RNA was purified using polydT conjugated beads to extract polyA-tagged mRNA, which was subsequently cleaved into ~200 bp fragments by treatment with divalent cations at 75°C. The first strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with random hexamer primers, and the second strand using RNase H (Invitrogen) and DNA polymerase I (New England BioLabs). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina Genome Analyzer II.

After removal of adapter sequences, raw reads were filtered according to stringent criteria [52]. The clean reads generated were used for all subsequent analyses. Trinity was used to assemble the paired-end short reads into contigs.

Functional annotation

The EST sequences were searched against the NCBI non redundant protein database using BLASTX with an E-value cutoff of 1e-5. The blast output in XML format was then annotated by Blast2go using default parameters. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) was a universally acknowledged database for delineating networks of macromolecular interaction within cells. Pathway annotation was conducted using the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS) web server and Single-directional Best Hit (SBH) method against representative sets for eukaryotes. GO enrichment was analyzed with WEGO.

Ortholog identification and comparison

Bi-directional BLASTN searches were performed for the transcriptomes of C. mandshurica and C. avellana. The reciprocal best blast hits were considered as orthologs. Orthologs with sequence identity lower than 90% were discarded in further GO analyses in order to exclude distant homologs due to the incomplete and fragmentary nature of transcriptomes. Two types of sequence variations were studied in GO enrichment analyses. One type focuses on orthologs with relatively low sequence identity, which includes 10.4% of all orthologs with sequence identity less than 97%. The other focuses the presence of gaps in local alignments of orthologs as shown in BLASTN outputs. GO terms of all orthologs and these two types of orthologs were extracted from Blast2go outputs. GO enrichment analyses were carried out on WEGO server. GO terms with p-value of Pearson Chi-square test below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The identification of genes involved in taxol synthesis

Genes related to taxol syntheses were identified by extensively parsing gene descriptions in the XML-formatted BLASTX output using key words of all the corresponding enzymes. The potential genes were further manually verified.

In order to compare these sequences with homologous genes in other species, we used the prototype genes responsible for taxol synthesis in yew as query sequences to search against the NCBI non redundant protein database using BLASTP. The top protein hits from fungi and plants were extracted.

DATA Availability

Reads are deposited at NCBI SRA (SRR857924).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HM and JL analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. ZL acquired the leaf sample. BL prepared the mRNA for sequencing. QQ provided helpful suggestion in data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The assembled EST sequences of C. mandshurica in fasta format.

GO terms for orthologs with sequence identity lower than 97.

GO terms for orthologs with INDEL.

GO terms for all orthologs.

Contributor Information

Hui Ma, Email: dnacode@gmail.com.

Zhiqiang Lu, Email: luzhiqiang2010@gmail.com.

Bingbing Liu, Email: liubb07@lzu.edu.cn.

Qiang Qiu, Email: qiuq04@gmail.com.

Jianquan Liu, Email: liujq@nwipb.ac.cn.

Acknowledgement

This study is supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program, No. 2013AA100605), Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (Grant No. 20100211110008) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (lzujbky-2009-k05).

References

- Zhang Y, Li F, Tao R, Li Z, Liang Y. An investigation of wild Corylus resource at Changbai Mountains. J Jilin Agri Sci. 2007;32(5):56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. Exploring the utilization of Corylus. Farm Prod Proc. 2010;1:24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Huang M. Selecting for excellent clones of Castanea henryi. Fujian Agri Sci Technol. 2012;12:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhang H, Zhang W. The new application of Corylus. Spel Econ Anim Plant. 1998;6:38. [Google Scholar]

- Plosker GL, Hurst M. Paclitaxel: a pharmacoeconomic review of its use in non-small cell lung cancer. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19(11):1111–1134. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200119110-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Mahdi H, Bryant C, Shah JP, Garg G, Munkarah A. Clinical trials and progress with paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. Inter J Women’s Health. 2010;2:411–427. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S7012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradishar WJ. Taxanes for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Bre Can: Basic Clin Res. 2012;6:159–171. doi: 10.4137/BCBCR.S8205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wani MC, Taylor HL, Wall ME, Coggon P, McPhail AT. Plant antitumor agents. VI. Isolation and structure of taxol, a novel antileukemic and antitumor agent from Taxus brevifolia. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93(9):2325–2327. doi: 10.1021/ja00738a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidensek N, Lim P, Campbell A, Carlson C. Taxol content in bark, wood, root, leaf, twig, and seedling from several Taxus species. J Nat Prod. 1990;53(6):1609–1610. doi: 10.1021/np50072a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Service RF. Hazel trees offer new source of cancer drug. Science. 2000;288(5463):27–28. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.27a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestoso F, Ottaggio L, Armirotti A, Balbi A, Damonte G, Degan P, Mazzei M, Cavalli F, Ledda B, Miele M. In vitro cell cultures obtained from different explants of Corylus avellana produce Taxol and taxanes. BMC Biotechnol. 2006;6(1):45. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-6-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman A, Shahidi F. Paclitaxel and other taxanes in hazelnut. J Funct Foods. 2009;1(1):33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2008.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaggio L, Bestoso F, Armirotti A, Balbi A, Damonte G, Mazzei M, Sancandi M, Miele M. Taxanes from Shells and Leaves of Corylus avellana. J Nat Prod. 2007;71(1):58–60. doi: 10.1021/np0704046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo F, Fei X, Tang F, Li X. Simultaneous determination of Paclitaxel in hazelnut by HPLC-MS/MS. For Res. 2011;24(6):779–783. [Google Scholar]

- Miele M, Mumot A, Zappa A, Romano P, Ottaggio L. Hazel and other sources of paclitaxel and related compounds. Phytochem Rev. 2012;11(2–3):211–225. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X-K, Liu J-J. New source for L-iditol and taxanes. Nat Preced. 2008. http://precedings.nature.com/documents/1502/version/1

- Bemani E, Ghanati F, Rezaei A, Jamshidi M. Effect of phenylalanine on taxol production and antioxidant activity of extracts of suspension-cultured hazel (Corylus avellana L.) cells. J Nat Med. 2013;67(3):446–451. doi: 10.1007/s11418-012-0696-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D, Su S, Ni B, Wang W, Meng X, Liu W. Germplasm resources investigation and utilization prospects of hazel in Small Xing’an Ridge region. Chin Agric Sci Bull. 2012;28(28):87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne CJ, Mehlenbacher SA, Smith DC. Sources of resistance to Eastern Filbert Blight in hazelnut. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1998;123(2):253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar TJ, Capik J, Zhao S, Zhang N. First report of Eastern Filbert Blight on Corylus avellana 'Gasaway’ and 'VR20-11’ caused by Anisogramma anomala in New Jersey. Plant Dis. 2010;94(10):1265–1265. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-06-10-0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang W. An investigation of wild Corylus resources in China. Journal of Liaoning Forestry Science and Technology. 1989;1:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Wang M, Liang W, Xie M, Li D. A study on cold resistance for filbert genus (Corylus L.) plants. J Jilin Fores Univ. 1994;3:166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ni B, Ni W, Xu X, Wang X. Hazel breeding research. Forest By-Product and Speciality in China. 2010;106(3):29–31. [Google Scholar]

- X-j Z, F-x D, R-q Z, G-x W, M-p Y, L-s L. Research on the compatibility of five Corylus species. J Cen South Univ Fores Technol. 2009;29(4):26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan V, Mehlenbacher SA. Interspecific hybridization in hazelnut (Corylus) J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2000;125(4):489–497. [Google Scholar]

- Liang W, Xie M, Dong D, Jiang Z. The breeding research for new Corylus cultivar. China Fruits. 2000;2:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Huang W, Zhou Z, Liu J, Wang Y, Su S, Zhai M. Genetic diversity of six Corylus species in China detected with microsatellite isolated from Corylus avellana. Scientia Silvae Sinicae. 2009;45(2):22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Li X, Wang Z, Xue C, Limin Z, Guo Y. Study on phylogenetic analysis of Corylus germplasm resouces with SSR molecular markers for Corylus avellana. J Northeast Agric Univ. 2011;42(4):129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley ER, Fox SE, Bryant DW, Sullivan CM, Priest HD, Givan SA, Mehlenbacher SA, Mockler TC. Assembly and characterization of the European hazelnut 'Jefferson’ transcriptome. Crop Sci. 2012;52(6):2679–2686. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2012.02.0065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min XJ, Butler G, Storms R, Tsang A. OrfPredictor: predicting protein-coding regions in EST-derived sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(suppl 2):W677–W680. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Thomson M, Bodles WJA, Crawford RMM, Hunt HV, Featherstone AW, Pellicer J, Buggs RJA. Genome sequence of dwarf birch (Betula nana) and cross-species RAD markers. Mol Ecol. 2013;22(11):3098–3111. doi: 10.1111/mec.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. BLAT—The BLAST-Like Alignment Tool. Genome Res. 2002;12(4):656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(18):3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(suppl 2):W182–W185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A, Cai L, Mrázek J, Malmberg RL. Mutational patterns in RNA secondary structure evolution examined in three RNA families. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e20484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier J, Sonenberg N. Insertion mutagenesis to increase secondary structure within the 5’ noncoding region of a eukaryotic mRNA reduces translational efficiency. Cell. 1985;40(3):515–526. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PH, Tiley LS, Cullen BR. Effect of RNA secondary structure on polyadenylation site selection. Genes Dev. 1991;5(7):1277–1284. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus CJ, Graveley BR. RNA structure and the mechanisms of alternative splicing. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21(4):373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauger DM, Siegfried NA, Weeks KM. The genetic code as expressed through relationships between mRNA structure and protein function. FEBS Lett. 2013;587(8):1180–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amini F, Ismail E. 3′-UTR variations and G6PD deficiency. J Hum Genet. 2013;58(4):189–194. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2012.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Fang L, Zheng H, Zhang Y, Chen J, Zhang Z, Wang J, Li S, Li R, Bolund L. et al. WEGO: a web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(suppl 2):W293–W297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z, Yang Y, Zhao N, Wang Y. Diversity of endophytic fungi and screening of fungal paclitaxel producer from Anglojap yew. Taxus x media. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13(1):71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Zhang P, Zhang M, Fu C, Yu L. Functional analysis of a WRKY transcription factor involved in transcriptional activation of the DBAT gene in Taxus chinensis. Plant Biol. 2013;15(1):19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nims E, Vongpaseuth K, Roberts SC, Walker EL. WITHDRAWN: TcJAMYC: A bHLH transcription factor that activates paclitaxel biosynthetic pathway genes in yew (This manuscript was accepted by the Journal of Biological Chemistry, but following acceptance discrepancies in some of the sequences used in the work were discovered. The manuscript was withdrawn, and additional work has been conducted. Submission of a new manuscript is anticipated.) J Biol Chem. 2009. http://www.jbc.org/content/early/2009/10/01/jbc.M109.026195

- Sun G, Yang Y, Xie F, Wen J-F, Wu J, Wilson IW, Tang Q, Liu H, Qiu D. Deep sequencing reveals transcriptome re-programming of Taxus × media cells to the elicitation with methyl jasmonate. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e62865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Tholl D, Bohlmann J, Pichersky E. The family of terpene synthases in plants: a mid-size family of genes for specialized metabolism that is highly diversified throughout the kingdom. Plant J. 2011;66(1):212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo BH, Wang YC, Hu H, Miao ZQ, Tang KX. An endophytic Taxol-producing fungus BT2 isolated from Taxus chinensis var. maire. Afr J Biotechnol. 2006;5(10):875–877. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Zhou P-P, Yu L-J. An endophytic taxol-producing fungus from Taxus media, Cladosporium cladosporioides MD2. Curr Microbiol. 2009;59(3):227–232. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Zhou X, Liu L, Lu J, Wang Z, Yu G, Hu L, Lin J, Sun X, Tang K. An efficient transformation system of taxol-producing endophytic fungus EFY-21 (Ozonium sp.) Afr J Biotechnol. 2010;9(12):1726–1733. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Q, Ma T, Hu Q, Liu B, Wu Y, Zhou H, Wang Q, Wang J, Liu J. Genome-scale transcriptome analysis of the desert poplar. Populus euphratica. Tree Physiol. 2011;31(4):452–461. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpr015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The assembled EST sequences of C. mandshurica in fasta format.

GO terms for orthologs with sequence identity lower than 97.

GO terms for orthologs with INDEL.

GO terms for all orthologs.

Data Availability Statement

Reads are deposited at NCBI SRA (SRR857924).