Abstract

This study examined the effects of calcium (Ca) gluconate on collagen-induced DBA mouse rheumatoid arthritis (CIA). A single daily dose of 200, 100 or 50 mg/kg Ca gluconate was administered orally to male DBA/1J mice for 40 days after initial collagen immunization. To ascertain the effects administering the collagen booster, CIA-related features (including body weight, poly-arthritis, knee and paw thickness, and paw weight increase) were measured from histopathological changes in the spleen, left popliteal lymph node, third digit and the knee joint regions. CIA-related bone and cartilage damage improved significantly in the Ca gluconate- administered CIA mice. Additionally, myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels in the paw were reduced in Ca gluconate-treated CIA mice compared to CIA control groups. The level of malondialdehyde (MDA), an indicator of oxidative stress, decreased in a dosedependent manner in the Ca gluconate group. Finally, the production of IL-6 and TNF-α, involved in rheumatoid arthritis pathogenesis, were suppressed by treatment with Ca gluconate. Taken together, these results suggest that Ca gluconate is a promising candidate anti-rheumatoid arthritis agent, exerting anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative and immunomodulatory effects in CIA mice.

Keywords: Calcium gluconate, Rheumatoid arthritis, Anti-inflammation, Anti-oxidation, Immunomodulation

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a human autoimmune disease characterized by chronic inflammation of the synovial membranes with concomitant destruction of cartilage and bone. The etiology and pathogenesis of RA are due to abnormalities in cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which play an important role in the development of RA (Feldmann et al., 1996b). In addition, the current view of the cytokine network in rheumatoid joints supports the notion that TNF-α activates a cytokine cascade characterized by the simultaneous production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and IL-6, and of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, IL-1Ra, and soluble TNF receptor (Feldmann et al., 1996a).

Epidemiological studies have reported an inverse correlation between the dietary intake of antioxidants and the incidence of RA (Bae et al., 2003). Methotrexate, etanercept and infliximab are widely used drugs in the treatment of RA, as they act as anti-immunomodulatory agents (Filippin et al., 2008). Antioxidants exerted favorable effects on RA, however, these were much lower than expected (Drabikova et al., 2009; Nagatomo et al., 2010). Recent clinical trials using TNF-α-neutralizing antibody and IL-1 receptor antagonists have been relatively successful, but were expensive and caused hypersensitivity to medication, and a possibility of serious infection (Slifman et al., 2003). Therefore, new drugs with fewer side effects and stronger potency for treating RA need to be developed.

Calcium (Ca) salts have shown some anti-inflammatory properties (Smith et al., 1994). Ca chloride used in the treatment of urticaria, acute edema, pruritus and erythema (Sollmann, 1942), Ca carbonate and Ca gluconate have been used to treat insect stings (Binder, 1989) and Ca hydroxide has been used to suppress periapical inflammation in dental practice (Frolova and Isakova, 1990). Ca gluconate has also been used to treat injuries resulting from direct contact with hydrofluoric acid (Bracken et al., 1985). It markedly reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α in chemical burns in rats (Cavallini et al., 2004). Ca gluconate enhanced antiinflammatory activities of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (Karnad et al., 2006) and Ca supplements are important alternative sources of Ca to minimize bone loss during aging (Shahnazari et al., 2009).

We hypothesized that Ca gluconate would have a protective effect against experimental RA and related articular bone loss. However, there are no studies showing the direct effects of Ca gluconate on collagen-induced rheumatoid arthritis (CIA), as the bioavailability of Ca varies in Ca supplements, and can be affected by such factors as disintegration, solubility, chelate formation, and food-drug interactions (Whiting and Pluhator, 1992). The DBA/1J mouse CIA model is a wellestablished model of human rheumatoid arthritis. It has been used to confirm the anti-rheumatoid arthritis effects of various drugs (Nandakumar and Holmdahl, 2006). Therefore, the object of this study was to ascertain the efficacy of Ca gluconate, a water-soluble Ca salt, on CIA mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and husbandry

Forty-eight male DBA/1J mice (5-week-old upon receipt; SLC, Japan; ANNEX I~IV) were used after acclimatization for 14 days. Animals were housed four or five per polycarbonate cage in a temperature (20-25℃)- and humidity (40-45%)-controlled room with a 12 hrs:12 hrs light:dark cycle. Feed (Samyang, Korea) and water were supplied ad libitum. All animals were fasted overnight before at immunization and sacrifice (about 18 hrs with ad libitum access to water) and treated according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Science, National Research Council, USA on 1996, Washington D.C. In this study, eight mice per groups; total 6 groups were divided.

Preparations and administration of test materials

Calcium gluconate, white powder, was purchased from Glucan corp. (CAS No. 299-28-5, purity; 98%, Pusan, Korea), and Enbrel (Wyeth Korea, Korea) 25 mg/0.5 ml vehicle packed in syringe, was purchased from local supplier.

All test materials were stored in a refrigerator to protect from light and moisture. In this study, we selected 200 mg/kg of Calcium gluconate were selected as the highest dosage, and 100 and 50 mg/kg were selected as the middle and lowest dosages using common ratio 2. In addition, 10 mg/kg Enbrel, TNF-α neutralizing antibody (injected three day-intervals) was used as reference drug. In the present study, 200, 100 and 50 mg/kg of Calcium gluconate was orally administered, once a day 40 days in a volume of 5 ml/kg of distilled water. In case of Enbrel, it subcutaneously injected three day-intervals from immunization to sacrifice diluted using saline at 10 mg/kg levels. In intact and CIA control, only distilled water was orally administered instead of test materials, once a day for 40 days from immunization.

Induction of CIA

CIA was induced according to the previous methods (Trentham et al., 1977); Mice were immunized intradermally at the base of tail with 100μg of type II collagen (Chondrex, WA, USA) emulsified with an equal volume of Freund’s complete adjuvant (Chondrex, WA, USA) and intraperitoneally boosted with type II collagen (100 μg in 0.05 M acetic acid) emulsified with an equal volume of Freund’s incomplete adjuvant (Chondrex, WA, USA) at 23 days after the initial immunization. In intact control mice, only vehicle, 0.05 M acetic acid were intradermally injected instead of collagen immunization and intraperitoneally administered instead of antigen boosting, respectively.

Changes in body weights

Changes of body weight were calculated at 1 day before immunization (Day-1), at immunization (Day 0), 1, 7, 14, 21, 23 (at antigen boosting), 28, 35 and 39 days after immunization with at a termination using an automatic electronic balance (Precisa Instrument, Switzland). At immunization (initiation of administration) and at a termination, all experimental animals were overnight fasted (water was not; about 12 hrs) to reduce the differences from feeding.

Estimation of clinical arthritis indexes in CIA

The clinical severity of arthritis in all four paws of mice was evaluated in a triple-blind fashion by a previous published scoring system (Brahn et al., 1998). Briefly, 0=normal; 1=mild, apparent swelling limited to individual digits; 2=moderate, redness, and swelling of the ankle; 3=redness and swelling of the paw including digits; and 4=maximally inflamed limb with involvement of multiple joints. The arthritis score for each mouse was the sum of four paws, with the highest score of 16 for each mouse, and recorded at antigen boosting (Day 23), 24, 25, 26, 27, 30, 33, 36, 39 and 40 days after immunization.

Paw and knee thickness measurement

The thickness of left hind paw and knee was measured using an electronic digital caliper (Mytutoyo, Japan) and recorded at antigen boosting (Day 23), 24, 25, 26, 27, 30, 33, 36 and 39 days after immunization. In addition, to reduce the individual differences from start of measurements, the changes after antigen challenges were also calculated.

Organ weight measurements

At sacrifice, the spleen, left hind paw and left popliteal lymph nodes were collected after connective tissues, muscles and debris remove. The weight of organs or paw was calculated at g levels regarding absolute wet-weights. To reduce the individual body weight differences, the relative weight (%) was calculated using body weight at sacrifice and absolute weight.

Measurement of MPO contents

Collected paws were homogenized (50 mg/ml) in 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (Sigma, MO, USA) in 10 mM 3-N-morpholinopropanesulfonic acid (Sigma, MO, USA) and centrifuged at 15,000 g for 40 min. The suspension was then sonicated three times for 30 seconds. An aliquot of supernatant (20 μl) was mixed with a solution of 1.6 mM tetra-methyl-benzidine (Wako, Japan) and 1 mM hydrogen peroxide (Daejung, Korea). Activity was measured spectrophotometrically as the change in absorbance at 650 nm at 37℃, using a microplate reader (Liaudet et al., 2002). Results are expressed as milliunits (mU) of MPO activity per mg of protein, which were determined with the Bradford assay.

Measurement of MDA contents

MDA formation was utilized to quantify the lipid peroxidation in the mouse paws and measured as thiobarbituric acid-reactive material. Tissues were homogenized (100 mg/ml) in 1.15% KCl buffer. Two hundred microliters of the homogenates were then added to a reaction mixture consisting of 1.5 ml 0.8% thiobarbituric acid (Sigma, MO, USA), 200 μl 8.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (Wako, Japan), 1.5 ml 20% acetic acid (pH 3.5), and 600 μl distilled water. The mixture was then heated at 90℃ for 45 min. After cooling to room temperature, the samples were cleared by centrifugation (10,000 g for 10 min) and their absorbance measured at 532 nm, using 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane as an external standard (Liaudet et al., 2002). The level of lipid peroxides was expressed as nmol of MDA/mg of protein.

Measurement of paw cytokine contents

Paws were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen; the sample was then homogenized in 700 μl of a TRIS-HCl buffer containing protease inhibitors. Samples were centrifuged for 30 min and the supernatant frozen at -80℃ until assay. Cytokine levels were determined using commercial ELISA kit (Mabley et al., 2002).

Measurement of splenocyte cytokine productions

Mouse spleens were collected for cell preparation and washed twice with PBS. The spleens were minced and the red blood cells were lysed with 0.83% ammonium chloride (Daejung, Korea). The cells were filtered through a cell strainer and centrifuged at 1,300 rpm at 4℃ for 5 min. The cell pellets were resuspended in RPMI 1,640 medium and plated in 24-well plates (Corning, NY, USA) at a concentration of 1×106 cells/well. Isolated splenocytes were cultured for 72 h. The amounts of TNF-α and IL-6 in the culture supernatants were measured by ELISA (Cho et al., 2009). The amounts of cytokines present in the test samples were determined from standard curves constructed with serial dilutions of recombinant murine TNF-α and IL-6. The absorbance was determined with an ELISA microplate reader at 405 nm.

Histopathology

The knee joints parts were sampled with the joint capsules preservation with total left hind paw, and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. After 5 days of fixation, they were decalcified using decalcifying solution [24.4% formic acid, and 0.5 N sodium hydroxide] for 5 days (mixed decalcifying solution was exchanges once a day for 5 days). After that, median joint parts were longitudinally trimmed or third digits were crossly trimmed, and embedded in paraffin, sectioned (3-4 μm) and stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E). The histological profiles of the knee joints and third digits were observed as compared with the intact control. In addition, spleen and left popliteal lymph nodes were sampled and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. After paraffin embedding, 3-4 μm sections were prepared. Representative sections were stained H&E for light microscopical examination. After that the histological profiles of individual organs were observed.

Semiquantitative scoring system: Three pathologists who were kept unaware of the source of the tissues independently evaluated each section on a 3-point scale (Ono et al., 2004): 0=normal, 1=infiltration of inflammatory cells, 2=synovial hyperplasia and pannus formation, and 3=bone erosion and destruction.

Histomorphometry: The thickness of articular surface (including compact bone and articular cartilages) of tibia and femur (μm/bone), articular cartilage thickness of tibia and femur (μm/bone), infiltrated inflammatory cell numbers of left knee cavity and cutaneous regions of third digits (cells/mm2), dorsum digit skin thicknesses around third digits (μm/digit), cortical bone thickness of third digits (μm/digit), total (central regions; mm/spleen) and white pulp (mm/pulp) thicknesses of spleen with numbers of white pulp (pulps/mm2), and total (central regions) and cortex thicknesses (mm/lymph node) of left popliteal lymph were measured as histomorphometrical analyses at prepared histological samples using digital image analyzer (DMI-300, DMI, Korea).

The histopathologist was blinds to group distribution when this analysis was made.

Statistical analyses

Multiple comparison tests for different dose groups were conducted. Variance homogeneity was examined using the Levene test. If the Levene test indicated no significant deviations from variance homogeneity, the obtain data were analyzed by one way ANOVA test followed by least-significant differences (LSD) multi-comparison test to determine which pairs of group comparison were significantly different. In case of significant deviations from variance homogeneity were observed at Levene test, a non-parametric comparison test, Kruskal-Wallis H test was conducted. When a significant difference is observed in the Kruskal-Wallis H test, the Mann- Whitney U test was conducted to determine the specific pairs of group comparison, which are significantly different. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows (Release 14K, SPSS Inc., USA). In addition, the percent changes as compared with CIA control were calculated to help the understanding of the efficacy of test materials, and the percent changes between intact and CIA control were also calculated to observe induction status of CIA in the present study.

RESULTS

Changes in body weight

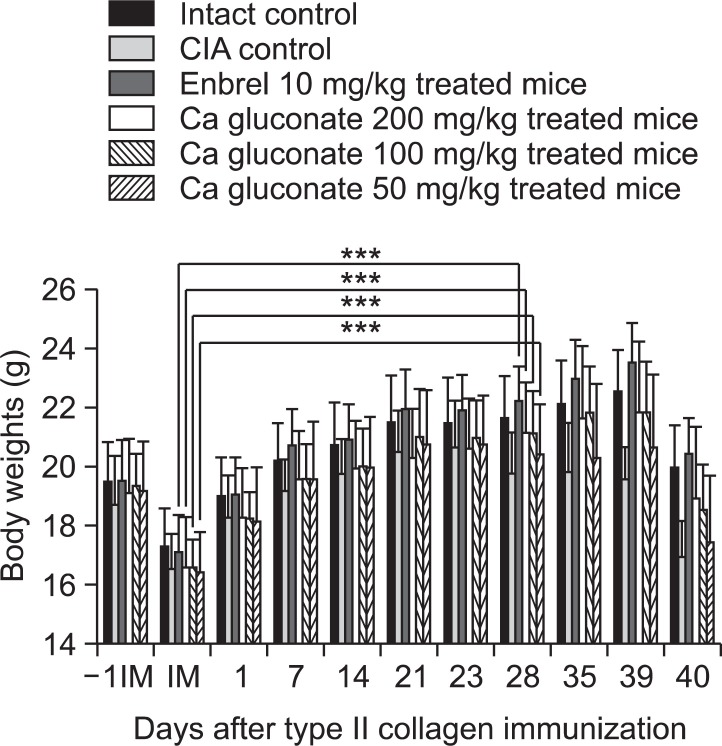

Significant decreases in body weight were detected from 28 days after immunization (5 days after antigen boosting) in the CIA control group compared with an intact control. Body weight gains were also significantly decreased after antigen boosting and during experimental periods. However, the body weights of ENBREL mice, and mice treated with the three doses of Ca gluconate, increased markedly from 28 days after immunization, as did the body weights after antigen boosting and during experimental periods (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Ca gluconate inhibited changes in body weight in CIA mice. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n=8). ***p<0.001 compared with the mean body weights at immunization. -1IM: 1 day before immunization, IM: immunization (start of administration of test materials); 23, day of antigen challenge. All animals were fasted overnight before immunization and sacrifice (40 days after immunization).

Therapeutic effects on rheumatoid arthritis

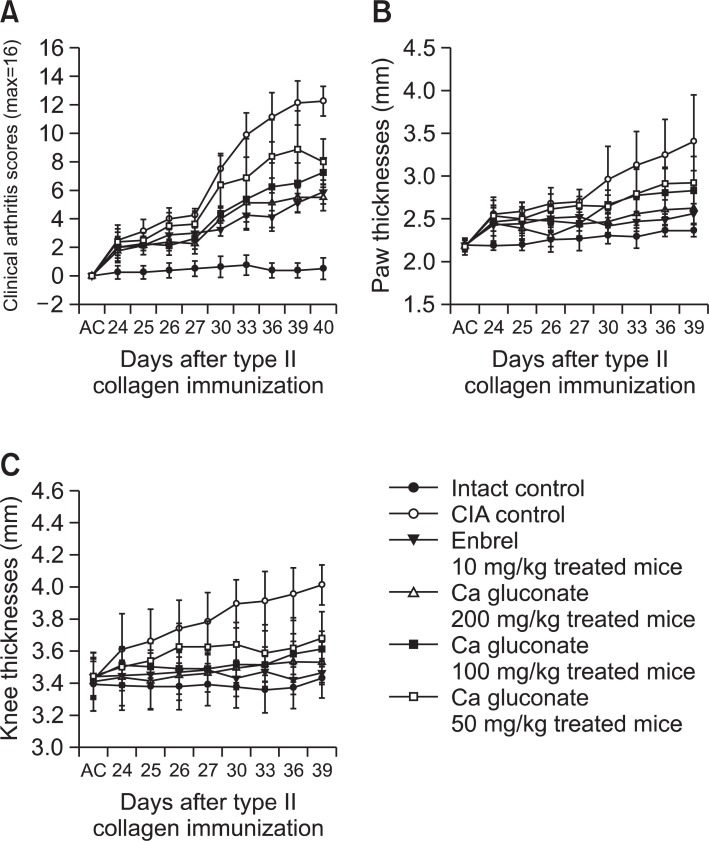

Clinical arthritis scores were significantly higher from 24 days after immunization (1 day after antigen boosting) in the CIA control compared with the intact control. However, significant decreases in clinical arthritis scores were detected from 26 days after immunization in the ENBREL- and Ca gluconate (100 and 200 mg/kg)-treated mice, and also in the Ca gluconate (50 mg/kg)-treated mice from 33 days after immunization, as compared with the CIA control mice (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Ca gluconate reduced clinical arthritis scores, and paw and knee thickness in Ca gluconate-treated CIA mice. (A) Significant decreases in clinical arthritis scores were detected in Ca gluconatetreated mice (B) Paw thickness was significantly (p<0.01 or p<0.05) reduced in Ca gluconate-treated mice (a, b) compared with CIA control mice. (C) Knee thickness was significantly (p<0.01 or p<0.05) reduced in Ca gluconate-treated mice (a, b) compared with CIA control mice. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n=8). AC; day of antigen challenge at 23 days after immunization. All animals were fasted overnight before immunization.

There was a significant increase in paw thickness from 24 days after immunization (1 day after antigen boosting) and a significant increase in knee thickness from 25 days after immunization (2 days after antigen boosting) in the CIA control as compared with the intact control. Paw and knee thickness after antigen challenge also increased significantly.

Paw thickness in ENBREL and 200 mg/kg Ca gluconatetreated mice decreased significantly from 25 days after immunization. Mice treated with 100 and 50 mg/kg Ca gluconate also exhibited decreased paw thickness from 26 and 30 days after immunization, respectively. In addition, after antigen challenge, paw thickness decreased in the ENBREL group, and in all three Ca gluconate-treated groups, as compared with the CIA control (Fig. 2B).

Knee thickness in ENBREL and 200 mg/kg Ca gluconatetreated mice decreased significantly from 24 days after immunization, and from 25-27 days after immunization in 100 and 50 mg/kg Ca gluconate-treated mice as compared with CIA control mice. The changes in knee thickness after antigen challenge also decreased significantly in the ENBREL group, and in all three Ca gluconate-treated groups, as compared with the CIA control (Fig. 2C).

The absolute and relative weights of the left paw, spleen and left popliteal lymph nodes were significantly higher at sacrifice in the CIA control, compared with the intact control. However, in the ENBREL group, and in all three Ca gluconatetreated groups, these weights were lower than in the CIA control mice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Changes of left hind paw and secondary lymphatic organs detected after treatment of enbrel and three different dosages of calcium gluconate in CIA mice

| Groups | Paw weights | Spleen weights | Left popliteal lymph nodes weights | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Absolute | Relative | Absolute | Relative | Absolute | Relative | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Controls | ||||||||||||

| Intact | 0.133 ± 0.008 | 0.667 ± 0.022 | 0.047 ± 0.008 | 0.236 ± 0.028 | 0.003 ± 0.002 | 0.013 ± 0.009 | ||||||

| CIA | 0.202 ± 0.027a | 1.195 ± 0.188a | 0.101 ± 0.009a | 0.599 ± 0.075a | 0.015 ± 0.004a | 0.088 ± 0.025a | ||||||

| Reference | ||||||||||||

| Enbrel | 0.136 ± 0.004c | 0.665 ± 0.037c | 0.062 ± 0.004a,c | 0.302 ± 0.022a,c | 0.005 ± 0.004c | 0.025 ± 0.020c | ||||||

| Calcium gluconate | ||||||||||||

| 200 mg/kg | 0.128 ± 0.011c | 0.688 ± 0.121c | 0.055 ± 0.003b,c | 0.291 ± 0.022a,c | 0.007 ± 0.003b,c | 0.036 ± 0.017b,c | ||||||

| 100 mg/kg | 0.140 ± 0.018c | 0.763 ± 0.144c | 0.062 ± 0.008a,c | 0.335 ± 0.047a,c | 0.008 ± 0.003a,c | 0.041 ± 0.015a,c | ||||||

| 50 mg/kg | 0.154 ± 0.029d | 0.902 ± 0.243b,d | 0.074 ± 0.019a,d | 0.435 ± 0.141a,d | 0.011 ± 0.003a,c | 0.061 ± 0.017a,c | ||||||

Values are expressed as Mean ± SD, g (absolute weight) or % (relative weights vs body weights at sacrifice) of eight mice. CIA: collageninduced arthritis, Ca: calcium. ap<0.01 and bp<0.05 as compared with intact control. cp<0.01 and dp<0.05 as compared with CIA control.

Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory eff ects of Ca gluconate

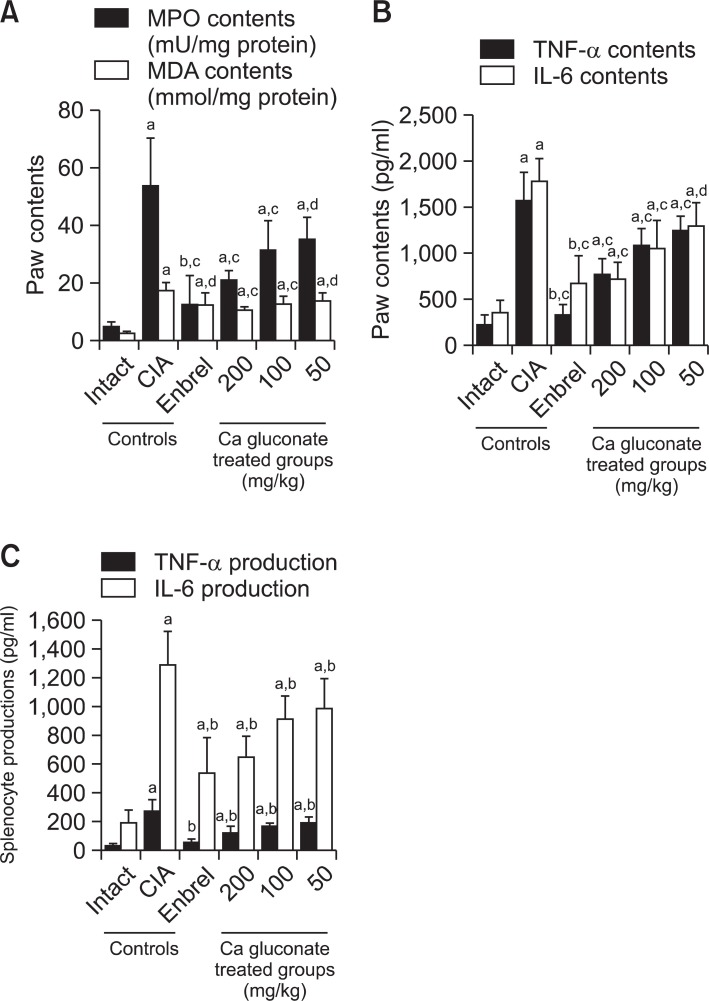

MPO and MDA were higher in right hind paw in the CIA control compared with the intact control group at sacrifice. However, for the ENBREL group, and in all three Ca gluconate-treated groups, the paw MPO and MDA levels were significantly lower compared with CIA control mice (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. Ca gluconate had a therapeutic effect on the CIA mice mediated by anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative and immunomodulatory effects. (A) Paw MPO and MDA contents of Ca gluconate-treated mice were lower compared to CIA control mice. (B) Paw TNF-α and IL-6 levels in Ca gluconate-treated mice were lower compared with CIA control mice. (C) Splenocyte TNF-α and IL-6 levels in Ca gluconatetreated mice were lower compared with CIA control mice. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n=8). ap<0.01 and bp<0.05 as compared with the intact control; cp<0.01 and dp<0.05 as compared with the CIA control.

There were significant increases in TNF-α and IL-6 in the right hind paw in the CIA control compared with the intact control at sacrifice. Moreover, splenocyte TNF-α and IL-6 production increased in the CIA control compared with the intact control.

However, for the ENBREL group, and in all three Ca gluconate- treated groups, TNF-α and IL-6 were significantly lower compared with the CIA control mice (Fig. 3B, C).

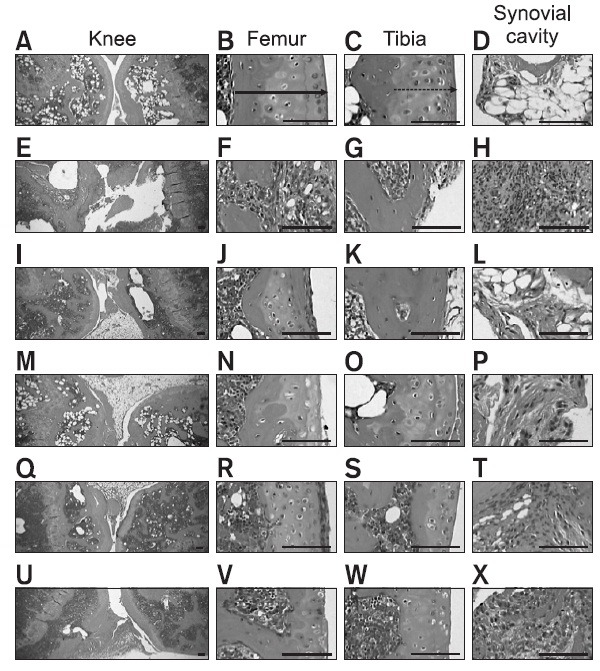

Histopathological changes in the knee and third digits

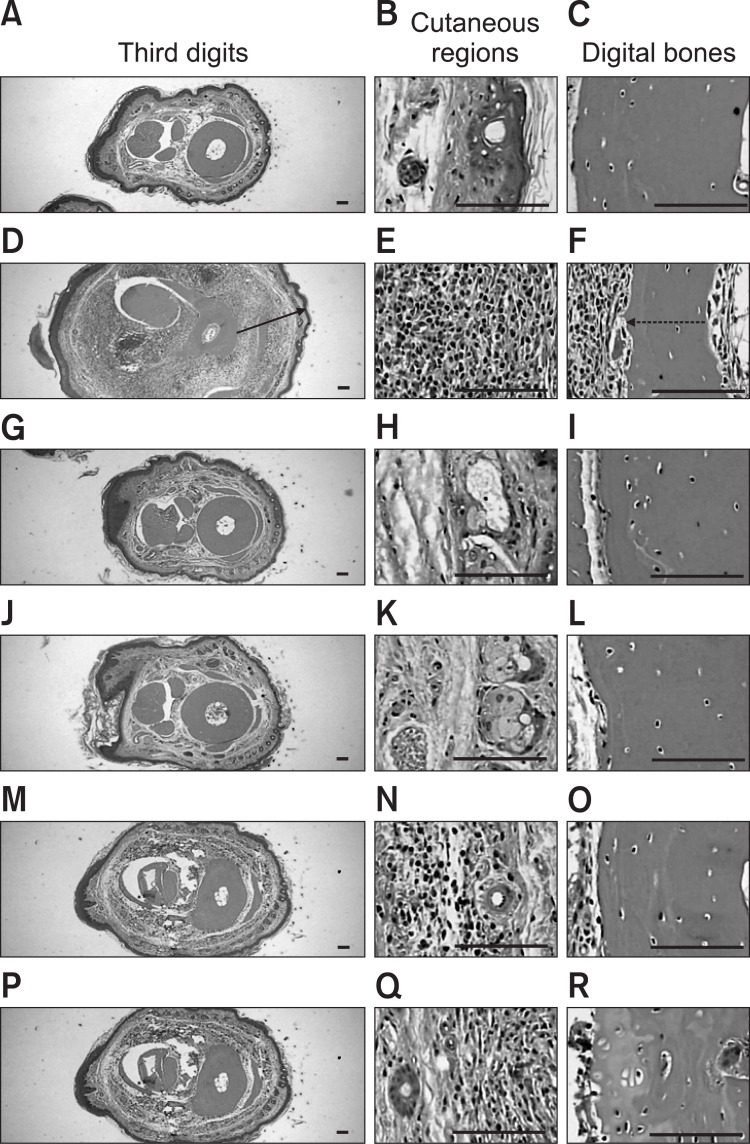

Marked decreases in articular cartilage and bone surfaces were detected in the both knee articular femur and tibia surfaces, where there was marked inflammatory cell infiltration into the synovial cavity in the CIA control mice. There were also dramatic edematous changes, inflammatory cell infiltration and erosive damage of the digital bones on the third digits of the CIA control mice. However, these histopathological changes indicative of CIA were dramatically decreased by ENBREL treatment and all three Ca gluconate doses, respectively (Fig. 4, 5).

Fig. 4. Histopathological profiles of the knee in the intact control (A-D), CIA control (E-H), ENBREL group (I-L), Ca gluconate-treated groups; 200 mg/kg (M-P), 100 mg/kg (Q-T) and 50 mg/kg (U-X). Marked decreases in the articular surfaces (cartilage and bone) were detected in the knee articular surfaces of the femur and tibia, with severe inflammatory cell infiltration into the synovial cavity in the CIA control mice. However, histopathological changes in the CIA group were decreased dramatically by treatment with Ca gluconate. The arrow indicates articular surface thickness. Dotted arrow indicates articular cartilage thickness. All were stained with H&E. Scale bars=160 μm.

Fig. 5. Histopathological profiles of the third digits in the intact control (A-C), CIA control (D-F), ENBREL group (G-I), Ca gluconatetreated groups; 200 mg/kg (J-L), 100 mg/kg (M-O) and 50 mg/kg (PR). Marked edematous changes, inflammatory cell infiltration and erosive damage of digital bones were detected on the third digits of the CIA control mice. However, these histopathological changes were decreased dramatically by treatment with Ca gluconate. The arrow indicates the dorsum paw skin thickness. Doted arrow indicates cortical bone thickness. All were stained with H&E. Scale bars=160 μm.

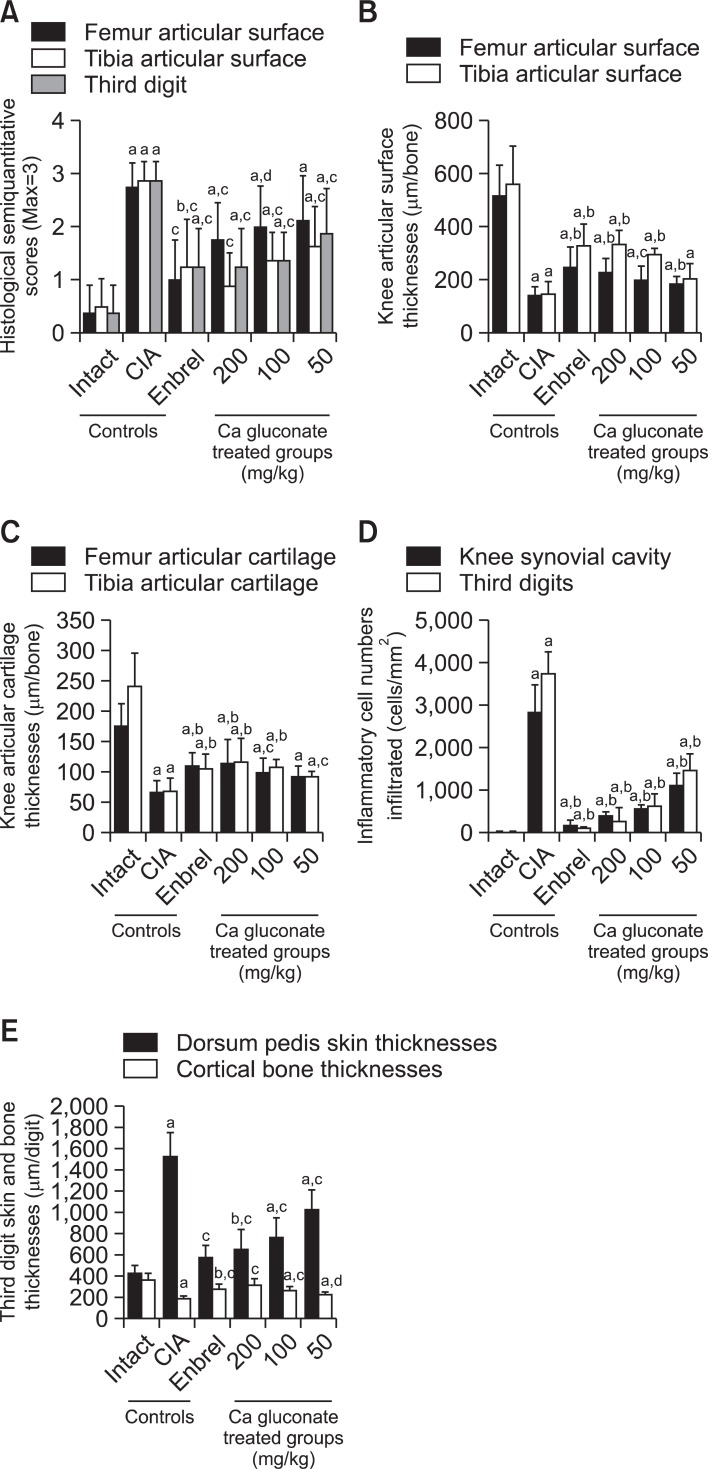

The semiquantitative scores increased significantly in the femur, tibia and third digits of the CIA control group compared with the intact control. However the semiquantitative scores of ENBREL and all Ca gluconate-treated mice were dramatically lower compared with the CIA control mice (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6. Ca gluconate ameliorated the histopathological changes of the knee and third digit. (A) The semiquantitative scores of Ca gluconate- treated mice were lower compared with the CIA control mice. (B) The knee articular surface thickness of Ca gluconate-treated mice was greater compared with the CIA control mice. Knee articular surface thicknesses are shown in Fig. 4 (arrow). (C) The knee articular cartilage thickness of Ca gluconate-treated mice was greater compared with the CIA control mice. Knee articular cartilage thicknesses are shown in Fig. 4 (dotted arrow). (D) Infiltrated inflammatory cells of Ca gluconate-treated mice were lower compared with the CIA control mice (E). Increases in the third digit dorsum pedis skin thickness and decreases in the cortical bone thickness were inhibited by treatment with Ca gluconate compared with the CIA control mice. Measurements of the third digit dorsum pedis skin (arrow) and cortical bone (dotted arrow) thicknesses are shown in Fig. 5. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n=8); ap<0.01 and bp<0.01 as compared with the intact control; cp<0.01 and dp<0.05 as compared with the CIA control.

Knee articular surface thickness, including compact bone and cartilage, and knee articular cartilage thickness were significantly less in the femur and tibia of the CIA control compared with the intact control, whereas the thickness of these sites in the ENBREL and Ca gluconate-treated mice were markedly higher than in CIA control mice (Fig. 6B, C).

Infiltration of inflammatory cells into the knee synovial cavity and third digits was significantly altered by Ca gluconate treatment. Significantly higher numbers of inflammatory cells infiltrated the knee synovial cavity and third digit cutaneous regions in the CIA control group compared with the intact control; however, in the ENBREL and Ca gluconate-treated mice the numbers of infiltrated cells were lower compared with the CIA control mice (Fig. 6D).

Significant changes of third digit dorsum pedis skin and cortical bone thickness were detected in the Ca gluconatetreated group. The third digit dorsum pedis skin thickness was significantly higher in the CIA control, however there were significant decreases in the ENBREL Ca gluconate-treated mice compared with the CIA control mice (Fig. 6E).

Histopathological changes of secondary lymphatic organs

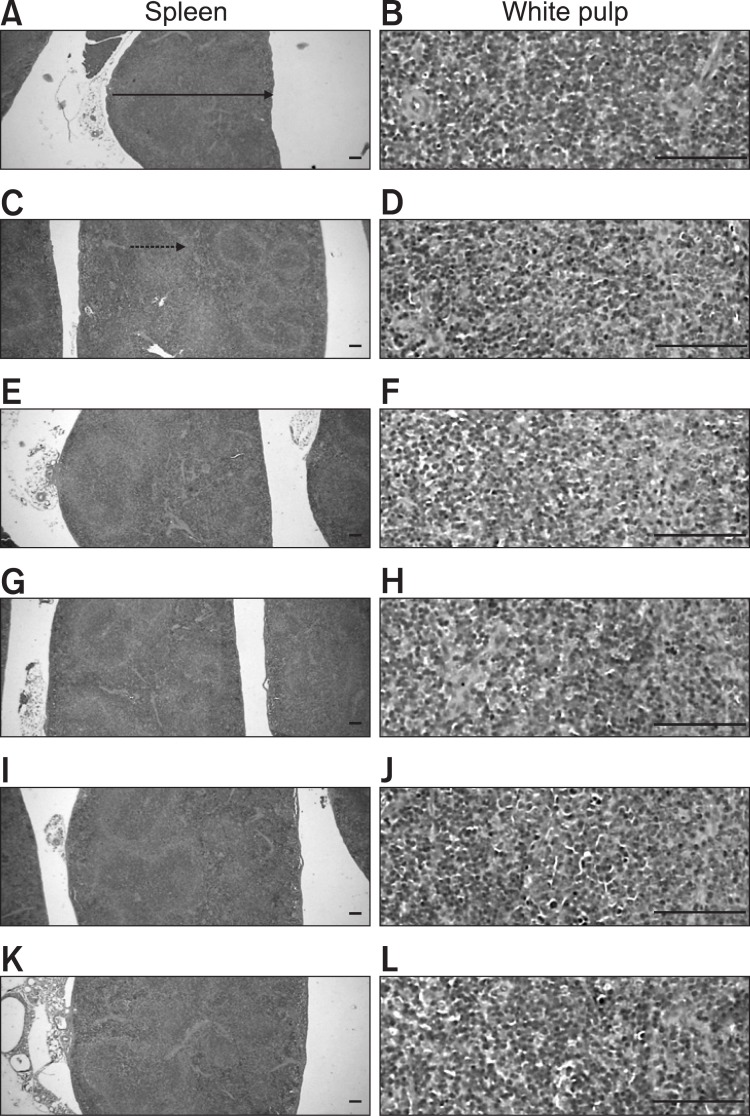

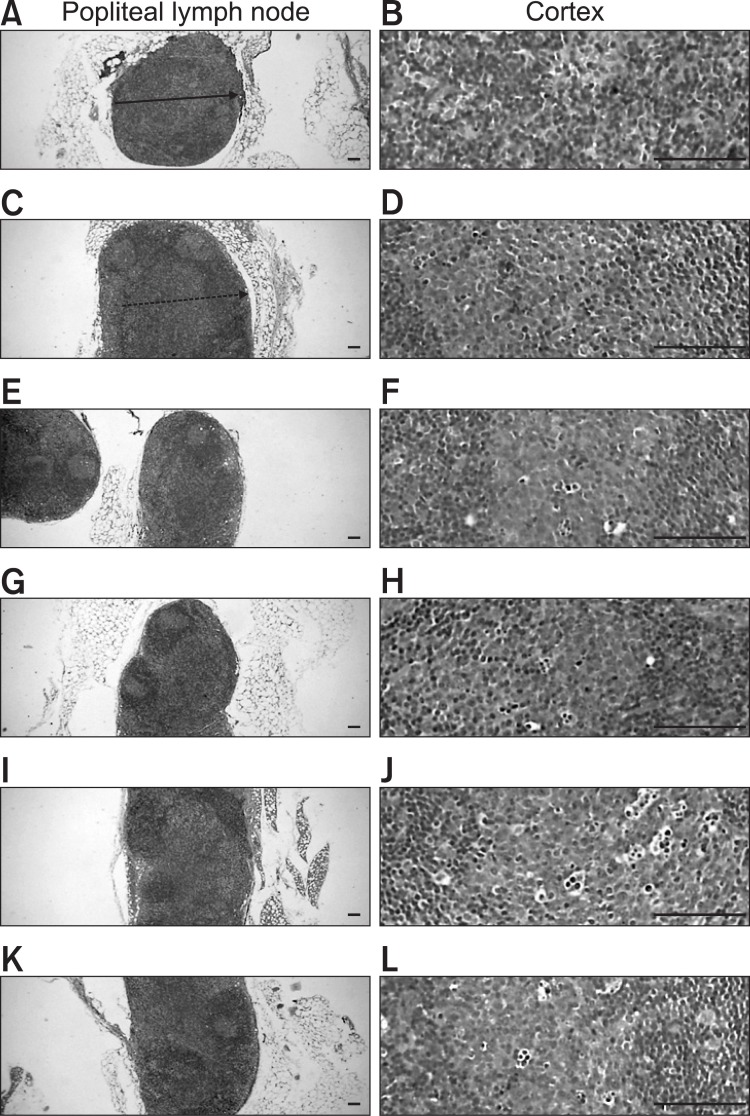

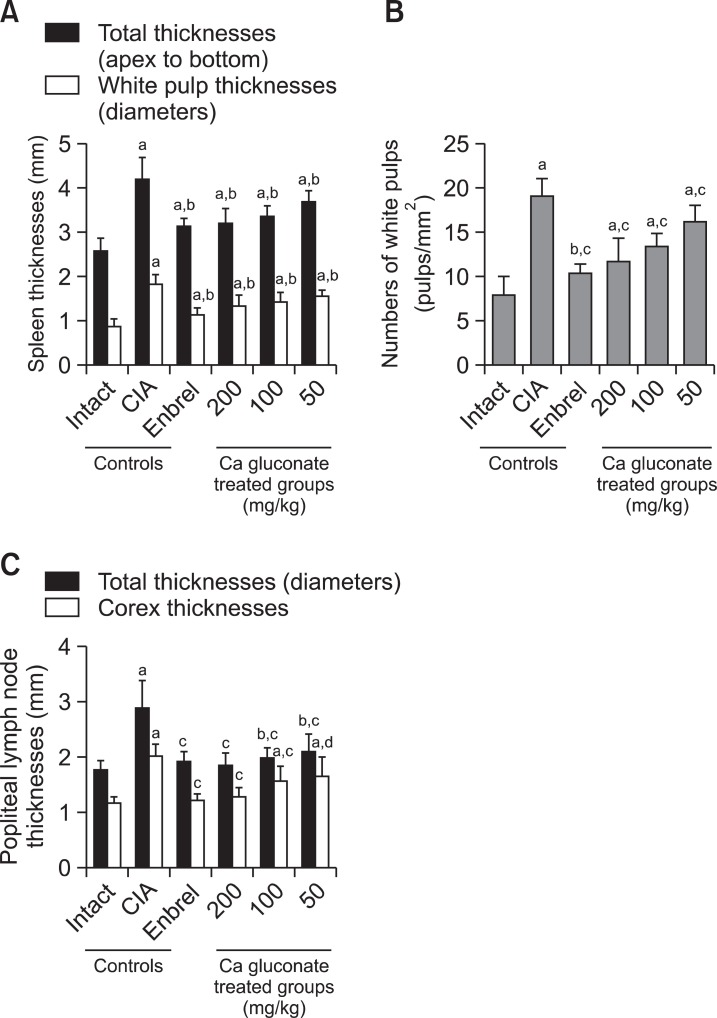

The CIA control mice demonstrated marked enlargement of the spleen and popliteal lymph nodes related to hyperplasia of the lymphoid cells in the white pulp of the spleen or cortex of lymph nodes. However, these histopathological changes decreased dramatically after ENBREL and Ca gluconate treatment (Fig. 7, 8). Significant decreases in total spleen thickness (around the central regions; from the apex to the base), splenic white pulp numbers, splenic white pulp thickness and popliteal lymph node total thickness were observed in the ENBREL and Ca gluconate-treated mice compared with the CIA control mice (Fig. 9).

Fig. 7. Histopathological profiles of the spleen in the intact control (A, B), CIA control (C, D), ENBREL group (E, F), Ca gluconate-treated groups; 200 mg/kg (G, H), 100 mg/kg (I, J) and 50 mg/kg (K, L). Marked enlargement of the spleen, related to hyperplasia of lymphoid cells in the white pulp, was detected in the CIA control mice. However, these histopathological changes decreased dramatically after treatment with ENBREL and all three doses of Ca gluconate. Arrow indicates the total spleen thickness. Doted arrow indicates white pulp. All were stained with H&E. Scale bars=160 μm.

Fig. 8. Histopathological profiles of the left popliteal lymph nodes in the intact control group (A, B), CIA control group (C, D), ENBREL group (E, F), and Ca gluconate-treated groups; 200 mg/kg (G, H), 100 mg/kg (I, J) and 50 mg/kg (K, L). Marked enlargement of popliteal lymph nodes, related to hyperplasia of lymphoid cells in the cortex of the lymph nodes, was detected in the CIA control mice. However, these histopathological changes decreased dramatically after treatment with ENBREL and all three doses of Ca gluconate. Arrow indicates the total popliteal lymph node thickness. Doted arrow indicates cortex thicknesses. All were stained with H&E. Scale bars=160 μm.

Fig. 9. Ca gluconate improved the histopathological changes of the secondary lymphatic organs. (A) The total spleen and white pulp thicknesses of Ca gluconate-treated mice were significantly decreased compared with the CIA control mice. Measurements of total spleen (arrow) and white pulp (dotted arrow) thicknesses are shown in Fig. 7. (B) The splenic white pulp of Ca gluconate-treated mice was significantly lower compared with CIA control mice. (C) The popliteal lymph node total and cortex thickness of Ca gluconate-treated mice were significantly lower compared with the CIA control mice. Measurement of lymph node total (arrow) and cortex (dotted arrow) thicknesses are shown in Fig. 8. Values are expressed as means ± SD (n=8); ap<0.01 and bp<0.05 compared with the intact control; cp<0.01 and dp<0.05 compared with the CIA control.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that CIA-related features, including body weight fluctuation (Ishikaw et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2007), polyarthritis (Larsen et al., 2008), knee and paw thickness, and paw weight increases (Ishikaw et al., 2002), were improved significantly in Ca gluconate-treated CIA mice. These results led us to hypothesize that Ca gluconate exerts an anti-inflammatory effect related to its antioxidant properties, since RA is closely related to inflammation of the synovial joints by CD4+ T cells, macrophages, plasma cells, and neutrophils (Feldmann et al., 1996a; Wolfe and Hawley, 1998).

We observed that increases in paw MPO levels in the CIA control were inhibited by Ca gluconate. In addition, increases in paw MDA levels were seen in the CIA control mice, which were inhibited by Ca gluconate (such as ENBREL) in a dosedependent manner. These results support other studies which show that Ca gluconate has a direct anti-inflammatory effect (Bracken et al., 1985; Cavallini et al., 2004; Karnad et al., 2006). Ca gluconate has anti-oxidative properties that may be involved the effects on the CIA. Generated oxygen metabolites play a pivotal role in the recruitment of neutrophils, primarily polymorphoneutrophils (PMNs), into injured tissues (Zimmerman et al., 1990). Activated PMNs are also a potential source of oxygen metabolites (Sullivan et al., 2000), and MPO is an activating cytotoxic enzyme released from PMNs (Iseri et al., 2005). Inflammation is directly correlated with oxidative stress (Lee and Ku, 2008), which is involved in the pathogenesis of CIA (Drabikova et al., 2009; Nagatomo et al., 2010).

Next, we analyzed the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α to ascertain that the anti-inflammatory effect of Ca gluconate is associated with these cytokines. As a result, increases in paw IL-6 and TNF-α were observed with increases in splenocyte IL-6 and TNF-α production, whereas Ca gluconate (such as ENBREL) inhibited the increase in cytokine activities in a dosedependent manner. These results show that Ca gluconate has immunomodulatory effects and that these may be involved in improving the CIA. Abnormal increases in cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α are involved in the pathogenesis of RA (Feldmann et al., 1996b). TNF-α is produced by a variety of cell types, including splenocytes, and is associated with critical events leading to T-lineage commitment and differentiation (Samira et al., 2004). TNF-α can enhance the in vivo immune response at low doses, avoiding weight loss or tissue toxicity. It enhances proliferation of B and T cells, and promotes the generation of cytotoxic T cells. In addition, it enhances IL-2-induced immunoglobulin production and augments IL-2-stimulated natural killer cell activity and proliferation of monocytes (Isaacs, 1995). It has also been suggested that IL-6 contributes to the development of arthritis (Van Snick, 1990). IL-6 is known to be present at high levels in the serum and synovial fluid of RA patients (Sethi et al., 2009; Zimmerman et al., 2010). IL-6 acts as a stimulator of both B and T cell functions; it promotes proliferation of plasmablastic precursors in the bone marrow, and their final stage of maturation into immunoglobulin-producing plasma cells, and participates in activation and proliferation of T cells (Van Snick, 1990).

We aimed to confirm the protective effects of Ca gluconate on histopathological changes in RA, including inflammation of peripheral synovial joints, articular cartilage and bone damages. We measured these histopathological changes using a semiquantitative score system which has been used to assess the efficacy of test materials on CIA (Ono et al., 2004; Cho et al., 2009). Our results show that Ca gluconate suppressed severe inflammation, and cartilage and bone erosions in CIA mice. In addition, enhanced immunity was inhibited by Ca gluconate treatment, such as ENBREL. Histopathologically, inflammation of peripheral synovial joints including infiltration of inflammatory cells, articular cartilage, and bone damage were induced in CIA. Signs of enhanced immunity (Yoon et al., 2010), such as increases in spleen and lymph node weights, enlargement of the spleen and lymph nodes due to hyperplasia of lymphoid cells, were detected in the CIA control group. The importance of secondary lymphoid organs in the development of RA was shown in previous studies (Newbould, 1964). Generally, secondary lymphoid organs are enlarged due to hyperplasia of lymphoid cells (Lee et al., 2007).

In conclusion, we suggest that Ca gluconate promises to be a new, effective anti-RA agent. Our results indicate that an oral dose of 200, 100 or 50 mg/kg Ca gluconate had favorable effects on the CIA mice, which were mediated by its anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative and immunomodulatory properties. Although marked favorable anti-CIA effects were detected in 50 mg/kg Ca gluconate-treated mice, these changes were restricted. Therefore, we consider a minimal effective dose of Ca gluconate to be 50 mg/kg, however, the optimal effective dosage is considered to be 100 mg/kg because all CIA-induced changes were significantly inhibited at this dosage.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. 2012-000940).

References

- 1.Bae S. C., Kim S. J., Sung M. K. Inadequate antioxidant nutrient intake and altered plasma antioxidant status of rheumatoid arthritis patients. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. (2003);22:311–315. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binder L. S. Acute arthropod envenomation. Incidence, clinical features and management. Med. Toxicol. Adverse Drug Exp. (1989);4:163–173. doi: 10.1007/BF03259994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bracken W. M., Cuppage F., McLaury R. L., Kirwin C., Klaassen C. D. Comparative effectiveness of topical treatments for hydrofluoric acid burns. J. Occup. Med. (1985);27:733–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brahn E., Banquerigo M. L., Firestein G. S., Boyle D. L., Salzman A. L., Szabo C. Collagen induced arthritis: reversal by mercaptoethylguanidine, a novel antiinflammatory agent with a combined mechanism of action. J. Rheumatol. (1998);25:1785–1793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavallini M., de Boccard F., Corsi M. M., Fassati L. R., Baruffaldi Preis F. W. Serum pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemical acid burns in rats. Ann. Burns Fire Disasters. (2004);17:84–87. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho M. L., Heo Y. J., Park M. K., Oh H. J., Park J. S., Woo Y. J., Ju J. H., Park S. H., Kim H. Y., Min J. K. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract (GSPE) attenuates collagen-induced arthritis. Immunol. Lett. (2009);124:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drabikova K., Perecko T., Nosal R., Bauerova K., Ponist S., Mihalova D., Kogan G., Jancinova V. Glucomannan reduces neutrophil free radical production in vitro and in rats with adjuvant arthritis. Pharmacol. Res. (2009);59:399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldmann M., Brennan F. M., Maini R. N. Rheumatoid arthritis. Cell. (1996a);85:307–310. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldmann M., Brennan F. M., Maini R. N. Role of cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. (1996b);14:397–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filippin L. I., Vercelino R., Marroni N. P., Xavier R. M. Redox signalling and the inflammatory response in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. (2008);152:415–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frolova O. A., Isakova V. I. [The therapeutic effect of a biogenic paste in experimental chronic periodontitis]. Stomatologiia (Mosk) (1990);69:20–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isaacs A. Lymphokines and Cytokines. In Immunology an introduction (I. R. Tizard, Ed.) Saunders College Pub.; Philadelphia: (1995). pp. 155–169. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iseri S. O., Sener G., Yuksel M., Contuk G., Cetinel S., Gedik N., Yegen B. C. Ghrelin against alendronate-induced gastric damage in rats. J. Endocrinol. (2005);187:399–406. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishikaw J., Okada Y., Bird I. N., Jasani B., Spragg J. H., Yamada T. Use of anti-platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 antibody in the control of disease progression in established collagen-induced arthritis in DBA/1J mice. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. (2002);88:332–340. doi: 10.1254/jjp.88.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karnad A. S., Patil P. A., Majagi S. I. Calcium enhances anti-inflammatory activity of aspirin in albino rats. Indian J. Pharmacol. (2006);38:397–402. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.28205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen C., Ostergaard J., Larsen S. W., Jensen H., Jacobsen S., Lindegaard C., Andersen P. H. Intra-articular depot formulation principles: role in the management of postoperative pain and arthritic disorders. J. Pharm. Sci. (2008);97:4622–4654. doi: 10.1002/jps.21346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H. S., Ku S. K. Effects of Picrorrhiza Rhizoma on acute inflammation in mice. Biomol. Ther. (2008);16:137–140. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2008.16.2.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee Y. C., Kim S. H., Roh S. S., Choi H. Y., Seo Y. B. Suppressive effects of Chelidonium majus methanol extract in knee joint, regional lymph nodes, and spleen on collagen-induced arthritis in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. (2007);112:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liaudet L., Mabley J. G., Pacher P., Virag L., Soriano F. G., Marton A., Hasko G., Deitch E. A., Szabo C. Inosine exerts a broad range of antiinflammatory effects in a murine model of acute lung injury. Ann. Surg. (2002);235:568–578. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200204000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mabley J. G., Liaudet L., Pacher P., Southan G. J., Groves J. T., Salzman A. L., Szabo C. Part II: beneficial effects of the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst FP15 in murine models of arthritis and colitis. Mol. Med. (2002);8:581–590. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagatomo F., Gu N., Fujino H., Okiura T., Morimatsu F., Takeda I., Ishihara A. Effects of exposure to hyperbaric oxygen on oxidative stress in rats with type II collagen-induced arthritis. Clin. Exp. Med. (2010);10:7–13. doi: 10.1007/s10238-009-0064-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nandakumar K. S., Holmdahl R. Antibody-induced arthritis: disease mechanisms and genes involved at the effector phase of arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. (2006);8:223. doi: 10.1186/ar2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newbould B. B. Lymphatic drainage and adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. (1964);45:375–383. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ono Y., Inoue M., Mizukami H., Ogihara Y. Suppressive effect of Kanzo-bushi-to, a Kampo medicine, on collagen-induced arthritis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. (2004);27:1406–1413. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samira S., Ferrand C., Peled A., Nagler A., Tovbin Y., Ben-Hur H., Taylor N., Globerson A., Lapidot T. Tumor necrosis factor promotes human T-cell development in nonobese diabetic/ severe combined immunodeficient mice. Stem. Cells. (2004);22:1085–1100. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-6-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sethi G., Sung B., Kunnumakkara A. B., Aggarwal B. B. Targeting TNF for treatment of cancer and autoimmunity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. (2009);647:37–51. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-89520-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahnazari M., Martin B. R., Legette L. L., Lachcik P. J., Welch J., Weaver C. M. Diet calcium level but not calcium supplement particle size affects bone density and mechanical properties in ovariectomized rats. J. Nutr. (2009);139:1308–1314. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.101071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slifman N. R., Gershon S. K., Lee J. H., Edwards E. T., Braun M. M. Listeria monocytogenes infection as a complication of treatment with tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agents. Arthritis Rheum. (2003);48:319–324. doi: 10.1002/art.10758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith M. M., Ghosh P., Numata Y., Bansal M. K. The effects of orally administered calcium pentosan polysulfate on inflammation and cartilage degradation produced in rabbit joints by intraarticular injection of a hyaluronate-polylysine complex. Arthritis Rheum. . (1994);37:125–136. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sollmann T. Manual of pharmacology and its applications to therapeutics and toxicology. WB Saunders Co.; Philadelphia: (1942). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan G. W., Sarembock I. J., Linden J. The role of inflammation in vascular diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. (2000);67:591–602. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.5.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trentham D. E., Townes A. S., Kang A. H. Autoimmunity to type II collagen an experimental model of arthritis. J. Exp. Med. (1977);146:857–868. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.3.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Snick J. Interleukin-6: an overview. Annu. Rev. Immunol. (1990);8:253–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whiting S. J., Pluhator M. M. Comparison of in vitro and in vivo tests for determination of availability of calcium from calcium carbonate tablets. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. (1992);11:553–560. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1992.10718261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolfe F., Hawley D. J. The longterm outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis: Work disability: a prospective 18 year study of 823 patients. J. Rheumatol. (1998);25:2108–2117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoon H. S., Kim J. W., Cho H. R., Moon S. B., Shin H. D., Yang K. J., Lee H. S., Kwon Y. S., Ku S. K. Immunomodulatory effects of Aureobasidium pullulans SM-2001 exopolymers on the cyclophosphamide-treated mice. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. (2010);20:438–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu P., Li X. Y., Wang H. K., Jia J. F., Zheng Z. H., Ding J., Fan C. M. Oral administration of type-II collagen peptide 250-270 suppresses specific cellular and humoral immune response in collagen-induced arthritis. Clin. Immunol. (2007);122:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmerman B. J., Grisham M. B., Granger D. N. Role of oxidants in ischemia/reperfusion-induced granulocyte infiltration. Am. J. Physiol. (1990);258:G185–190. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.258.2.G185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimmerman D. H., Taylor P., Bendele A., Carambula R., Duzant Y., Lowe V., O'Neill S. P., Talor E., Rosenthal K. S. CEL-2000: A therapeutic vaccine for rheumatoid arthritis arrests disease development and alters serum cytokine/chemokine patterns in the bovine collagen type II induced arthritis in the DBA mouse model. Int. Immunopharmacol. . (2010);10:412–421. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]