Abstract

Previous studies have demonstrated that repeated administration of the exogenous stress hormone corticosterone (CORT) induces dysregulation in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and results in depression and anxiety. The current study sought to verify the impact of catechin (CTN) administration on chronic CORT-induced behavioral alterations using the forced swimming test (FST) and the elevated plus maze (EPM) test. Additionally, the effects of CTN on central noradrenergic systems were examined by observing changes in neuronal tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunoreactivity in rat brains. Male rats received 10, 20, or 40 mg/kg CTN (i.p.) 1 h prior to a daily injection of CORT for 21 consecutive days. The activation of the HPA axis in response to the repeated CORT injections was confirmed by measuring serum levels of CORT and the expression of corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF) in the hypothalamus. Daily CTN administration significantly decreased immobility in the FST, increased open-arm exploration in the EPM test, and significantly blocked increases of TH expression in the locus coeruleus (LC). It also significantly enhanced the total number of line crossing in the open-field test (OFT), while individual differences in locomotor activities between experimental groups were not observed in the OFT. Taken together, these findings indicate that the administration of CTN prior to high-dose exogenous CORT significantly improves helpless behaviors, possibly by modulating the central noradrenergic system in rats. Therefore, CTN may be a useful agent for the treatment or alleviation of the complex symptoms associated with depression and anxiety disorders.

Keywords: Corticosterone, Depression, Anxiety, Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, Tyrosine hydroxylase, Catechin

INTRODUCTION

Stress-related diseases such as depression represent one of the greatest therapeutic challenges in the twenty-first century because of a relatively high lifetime prevalence rate and a high degree of co-morbidity (Aina and Susman, 2006). Depression is a worldwide problem for humans because of its substantial association with disabilities (Hill et al., 2012) such as sleep disturbances, low self-esteem, guilty feelings, and suicidal tendencies (Mackenzie et al., 2012). Thus, depression is considered a complex disorder and the mechanisms underlying its pathogenesis remain unclear. The severity of helplessness in depression is frequently combined with symptoms of anxiety (Evans et al., 2012) and, in fact, the manifestation of pure depression hardly appears without symptoms of anxiety (Mackenzie et al., 2012). Chronic exposure to stressful life events is an established and important risk factor for the development and maintenance of many psychological or helpless conditions in humans including major depression and anxiety (Uliaszek et al., 2010). It is also known that such diseases induce long-lasting deleterious effects on brain function (Anisman and Matheson, 2005).

Chronic stress results in a dysregulation of the hypothalamic- pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in the neuroendocrine system as evidenced by observations that the elevation of circulating corticosterone (CORT) levels disrupts the circadian regulation of CORT secretion as well as the glucocorticoid (GC) receptor- negative feedback circuit (Steiner et al., 2008). Activation of the HPA axis by high-dose CORT administration is associated with the development of psychic-related disorders, such as depression (Kutiyanawalla et al., 2011). Many studies have shown that the stimulation and sustained action of the HPA axis is attenuated via the negative feedback action of circulating GC following exogenous CORT administration, and this is closely associated with the development of psychosomatic disorders, which produce serious changes in affective behavior that are indicative of or consistent with depressive-like symptoms (Lee et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2011). Previous studies have shown that chronic exposure to CORT is causally related to depression-like behavioral impairments such as increased immobility time during the forced swimming test (FST) (Ago et al., 2013). In addition, several animal studies have found that chronic stress induces dysfunction of the HPA axis including morphological changes in the hypothalamus, hippocampus and amygdala (McLaughlin et al., 2007), alterations in a variety of neurotransmitters (Torres et al., 2002), reductions in body weight, and alterations in behavior (McLaughlin et al., 2007). Therefore, chronic CORT-induced physiological stress that is the result of HPA axis dysregulation increases depression- and anxiety-like behavior (Gregus et al., 2005).

Animal models of depression- and anxiety-like behaviors that utilize stressful stimuli are useful for determining the efficacy of antidepressant therapeutic candidates during drug screening (Dazzi et al., 2005). A number of antidepressant medicines have been developed and used clinically for the past several decades following basic and clinical studies (Molina-Hernández et al., 2012). However, most of these drugs are not very effective against the wide variety of complex depression symptoms, and most are associated with serious side-effects (Liebert and Gavey, 2009). Therefore, many studies suggested that a false positive or negative effect can be obtained by enhanced or diminished locomotor activity due to psycho-stimulating side-effects of the antidepressants in behavioral despair tests (Kwon et al., 2010). Thus, open-field test was intended to help exclude these false effects, which could influence behavioral despair tests. Therefore, much attention has been given to the use of naturally occurring compounds and their formulations as alternative therapeutic agents for the treatment of different psychosomatic disorders including depression and anxiety (Deligiannidis and Freeman, 2010).

Green tea is an extremely popular beverage worldwide and has been found to have antidepressant effects (Niu et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2012). Fresh green tea leaves are particularly rich in catechin (CTN) which constitutes 30-45% of solid green tea extract (Tanaka et al., 2009). In addition, CTN is a major, abundant flavonoid present in grape seed and black tea (Yilmaz and Toledo, 2004). It exhibits multiple physiological and biological properties and a number of studies have examined the antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory properties of CTN using a variety of assay systems, which have indicated its potential value for medicinal use (Li et al., 2009). Several studies using a rat model of ischemic reperfusion injury have shown that the administration of CTN may regulate the inflammation response via nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activation (Ashafaq et al., 2012). Additionally, CTN has been shown to prevent spatial learning and memory deficits via the decrease of β-amyloid (Aβ)1-42 oligomers and the upregulation of synaptic plasticity-related proteins in the hippocampi of mice (Li et al., 2009). Although a brief report on the anti-inflammatory activity and neuroprotective effects of CTN was published (Mandel et al., 2006; Burckhardt et al., 2008), it is currently unknown exactly whether CTN can improve the depression- and anxiety-like symptoms induced by repeated CORT injections in rats. Thus far, investigations of the medicinal effects of green tea, have focused on the cumulative activity of several compounds in green tea rather than that of a single compound (Dal Belo et al., 2011). In addition, most studies have evaluated the different synergistic bioactivities of all compounds present in tea extracts or have been focused mainly on the role of (-)- epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG; Chen et al., 2010). Therefore, the present study was designed to elucidate the individual antidepressant effects of the compound CTN.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the medicinal impacts of CTN on chronic stress-induced depression- and anxiety-related symptoms in an animal model using behavioral and neurobiological methodologies. To this end, using the forced swimming test (FST) and elevated plus maze (EPM) tests, the administration of CTN was evaluated for its efficacy in alleviating depression- and anxiety-like behavior in rats that were repeatedly exposed to exogenous CORT. In addition, the underlying neurobiological mechanism of these behaviors was investigated through an evaluation of central noradrenergic system following repeated CORT injections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats weighing 200-220 g (6 weeks-old) were obtained from Samtako Animal Co. (Seoul, Korea). The rats were housed in a limited access rodent facility with up to five rats per polycarbonate cage. The room controls were set to maintain the temperature at 22 ± 2℃ and the relative humidity at 55 ± 15%. Cages were lit by artificial light for 12 h each day. Sterilized drinking water and standard chow diet were supplied ad libitum to each cage during the experiments. The animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23), revised in 1996, and were approved by the Kyung Hee University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All animal experiments began at least 7 days after the animals arrived.

Experimental groups

This study was designed to explore the efficacy of CTN administration for healing repeated CORT-induced depression- and anxiety-like behavior in an animal model using behavioral and neurobiological methodologies. The rats were randomly divided into six groups of six to seven individuals each as follows: vehicle saline-injected group, instead of CORT (0.9% NaCl, s.c., SAL group, n=6), CORT-injected and non-treated group (40 mg/kg, s.c., CORT group; n=7), CORTinjected plus 10 mg/kg CTN-treated group (CORT+CTN10 group; n=6), CORT-injected plus 20 mg/kg CTN-treated group (CORT+CTN20 group; n=6), CORT-injected plus 40 mg/kg CTN-treated group (CORT+CTN40 group; n=6), and CORTinjected plus 10 mg/kg fluoxetine-treated group (CORT+FLX group as a positive control, n=6). Corticosterone (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA), which was dissolved in absolute ethanol and subsequently diluted in water to the final concentration of 10% ethanol, was administrated by subcutaneously (s.c) in a volume of 5 ml/kg once daily for 21 days (Huang et al., 2011; Yi et al., 2012). CTN and fluoxetine (FLX) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louise, MO, USA). CTN and FLX were administrated by intraperitoneally (i.p.) 1 h prior to the CORT injection for 21 days. As a vehicle control, animals in the SAL group were subcutaneously given the equivalent volumes in saline to the final concentration of 10% ethanol in a volume of 10 ml/kg. The SAL group and CORT group also received saline instead of CTN as a vehicle control in an equal volume for a period of 21 days. This CORT dose was selected because it induces serum levels of the steroid comparable to those elicited by substantial stress (Lee et al., 2012). The CORT and vehicle injections were given in the morning between 9 and 10 am once daily for 21 consecutive days. All drugs were freshly prepared right before every experiment.

The following parameters were measured to monitor the effects of the development of psychosomatic disorders by exogenous CORT administration: changes of body weight gains (at the beginning step of exogenous CORT administration), and serum CORT levels (after repeated CORT-induced depression- and anxiety-like symptoms). Behavioral testing for depression- and anxiety-like behavior was done 24 h after the end of the chronic physiological stress protocol. All rats sequentially performed to take the EPM on the 22th day after repeated CORT injection, and to take the FST test on the 23th day after repeated CORT injection. After the behavioral testing and body weighting, rats were sacrificed and brain tissues were immediately collected for experiments or stored at -70℃ for later use.

Measurement of sucrose intake

For the sucrose intake test, rats were trained to consume 1% sucrose solution prior to the start of the experiment. They were exposed to 1% sucrose solution for 48 h period in their home cages without any food or water available. Prior to each test, rats were food and water deprived for 10 h. Two bottles, one filled with 1% sucrose solution and the other with water were used. Placement of the bottles with sucrose vs. water was randomized across the test. Sucrose and water consumption was measured for the period of 1 h by weighing preweighed bottles at the end of the test. Sucrose preference was measured by calculating the proportion of sucrose consumption out of total consumption of liquid and was recorded once three days during the experiment for 21 consecutive days.

Corticosterone (CORT) analysis

Animals were killed by decapitation one day after behavioral measurements. Blood samples were collected for the determination of serum CORT levels. For this, the unanesthetized rats were rapidly decapitated, and blood was quickly collected via the abdominal aorta. Blood was centrifuged at 4,000 g for 10 min, and serum was collected and stored at -70℃ until use. The CORT concentration was measured by a competitive enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) using a rabbit polyclonal CORT antibody (OCTEIA Corticosterone kit; Alpco Diagnostics Co., Windham, NH, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples (or standard) and conjugate were added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 1 h at room temperature without blocking. After wells were washed several times with buffers and proper color developed, the optical density was measured at 450 nm using an ELISA reader (MutiRead 400; Authos Co., Vienna, Austria).

Forced swimming test (FST)

Forced swimming test, a representative behavioral test for depression, is frequently used to evaluate the activities of potential antidepressant drugs in rodent models. Forced immersion of rats in water for an extended period produces a characteristic behavior of immobility. The antidepressant treatments decrease the immobility behavior accompanying with an increase in the escape responses such as climbing and swimming. A transparent Plexiglas cylinder (20 cm diameter×50 cm height) was filled up to a depth of 30 cm with water at 25℃. At this depth, rats could not touch the bottom of the cylinder with their tails or hind limbs. On day 22, the rats in all groups were trained for 5 min by placing them in the water-filled cylinder. On day 23, animals were subjected to 5 min of forced swim, and escape behaviors (climbing and swimming) were determined. The duration of immobility was scored during the 5 min test period. The animals’ behavior was continuously recorded by experimenter-manual scoring during the testing session with an overhead video camera to tape behavior for later manual scoring. All of the behavioral scoring was done by a single trained rater, blind to experimental conditions. Several test sessions, chosen at random, were scored a second time by this rater to determine test-retest reliability, as previously described (Liu et al., 2012). The scorer would rate the rat’s behavior as one of the following three behaviors. Immobility behavior was calculated as the length of time in which the animal did not show escape responses (e.g., total time of the test minus time spent in climbing and swimming behaviors). The rats were judged to be immobile when it remained in the water without struggling and was making only those movements necessary to keep its head above water. Climbing behavior was defined as upward-directed movements of the forepaws alone the side of the swim chamber and swimming behavior was considered as movements throughout the swim chamber including crossing into another quadrant. After the test, the rat was removed from the tank, dried with a towel and placed back in its home cage. The water in the swim tank was changed between rats.

Elevated plus maze test (EPM)

The EPM test is a widely used behavioral test to assess anxiogenic or anxiolytic effects of pharmacological agents. Animals conduct anxiety-like behaviors usually show the reductions both in the number of entries and in the time spent in the open arms, along with an increase in the amount of time spent in the closed arms in the EPM. The elevated plus test was conducted. This apparatus consisted of two open arms (50×10 cm each), two closed arms (50×10×20 cm each) and a central platform (10×10 cm), arranged in a way such that the two arms of each type were opposite to each other. The maze was made from black Plexiglas and elevated 50 cm above the floor. Exploration of the open arms was encouraged by testing under indirect dim light (2×60 W).

At the beginning of each trial, animals were placed at the centre of the maze, facing a closed arm. During a 5 min test period, the following parameters were recorded: 1) number of open arm entries, b) number of closed arm entries, c) time spend in open arms, and d) time spent in closed arms. Entry by an animal into an arm was defined as the condition in which the animal has placed its four paws in that arm. The maze was cleaned with alcohol after each rat had been tested. The behavior in the maze was recorded using a video camera mounted on the ceiling above the center of the maze and relayed to the S-MART program (PanLab, Barcelona, Spain). Anxiety reduction, indicated by open arm exploration in the EPM, was defined as an increase in the numbers of entries into the open arms relative to total entries into either open or closed arm, and an increase in the proportion of time spent in the open arms relative to total spending time in either open or closed arm. Total arm entries were also used as indicators of changes in locomotor activities of the rats.

Open field test

Prior to forced swimming test, the rats were individually housed in a rectangular container that was made of dark polyethylene (60×60×30 cm) to provide best contrast to the white rats in a dimly lit room equipped with a video camera above the center of the room, and their locomotor activities (animal’s movements) were then measured. The locomotor activity indicated by the speed and the distance of movements was monitored by a computerized video-tracking system using SMART program (PanLab Co., Barcelona, Spain). After 5 min adaptation, the distance they traveled in the container was recorded for another 5 min. The locomotor activity was measured in centimeters. The floor surface of each chamber was thoroughly cleaned with 70% ethanol between tests. The number of line crossing (with all four paws) between the squares area was recorded for 5 min.

Immunohistochemistry of corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)

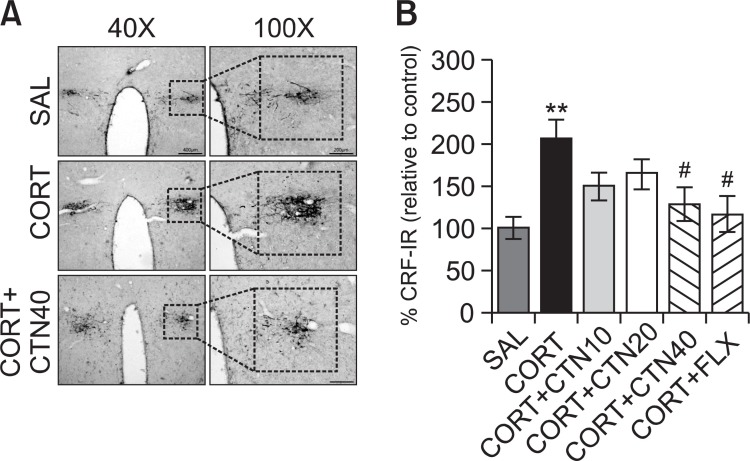

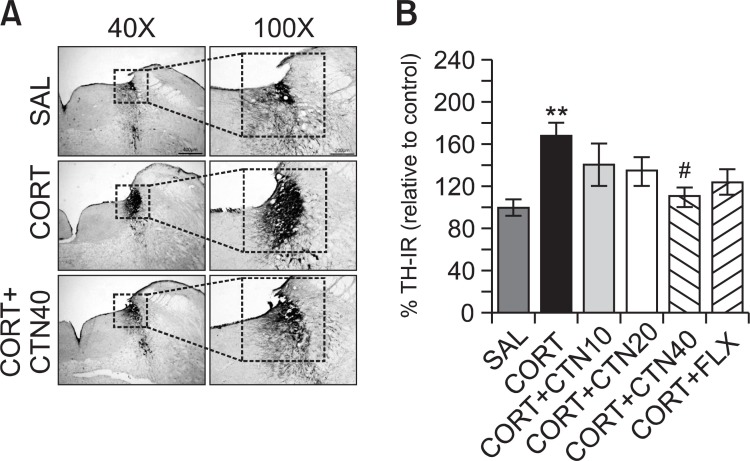

For immunohistochemical studies, the three rats in each groups were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (80 mg/kg, by intraperitoneal injection) and perfused through the ascending aorta with normal saline (0.9%) followed by 300 ml (per rat) of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphatebuffered saline (PBS). The brains were removed in a randomized order, post-fixed over-night, and cryoprotected with 20% sucrose in 0.1 M PBS at 4℃. Coronal sections 30 μm thick were cut through hypothalamus and locus coeruleus (LC) using a cryostat (Leica CM1850; Leica Microsystems Ltd., Nussloch, Germany). The sections were obtained according to the rat atlas of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). The sections were immunostained for CRF and TH expression using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) method. Briefly, the sections were incubated with primary goat anti-CRF antibody (1:500 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., California, CA, USA) and sheep anti-TH antibody (1:2000 dilution; Chemicon International Inc., Temecular, CA, USA) in PBST (PBS plus 0.3% Triton X-100) for 72 h at 4℃. The sections were incubated for 120 min at room temperature with secondary antibody. The secondary antibodies were obtained from Vector Laboratories Co. (Burlingame, CA, USA) and diluted 1:200 in PBST containing 2% normal serum. To visualize immunoreactivity, the sections were incubated for 90 min in ABC reagent (Vectastain Elite ABC kit; Vector Labs. Co., Burlingame, CA, USA), and incubated in a solution containing 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) as the chromogen. The sections were incubated in PBS containing 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 1 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Finally, the tissues were washed in PBS, followed by a brief rinse in distilled water, and mounted individually onto slides. Images were captured using the AxioVision 3.0 imaging system (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Oberkochen, Germany) and processed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). The sections were viewed at 40× or 100× magnification, and the numbers of CRF and TH labeled cells was quantified in the hypothalamus and LC. CRF- and TH-labeled cells were counted by an observer blinded to the experimental groups. Counting the immunopositive cells were performed within the square (400×400 μm), anatomically localized in hypothalamus and LC sections per rat brain according to the stereotactic rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). To detect CRF and TH-positive labeled cells, we used only hypothalamus and LC areas encircled with defined square in Fig. 1, 2. The background intensity of the hypothalamus and LC regions was captured and its mean and standard deviations (STD) were calculated. Immunohistochemistry analysis of tissue samples from 3 different animals was enough to show the changes of protein markers at molecular levels, as published in our previous studies (Lee et al., 2012). The counted sections were randomly chosen from equal levels of serial sections along the rostral-caudal axis. The stained cells of which intensities were reached to a defined value above the background were only considered as immunopositive cells. Distinct brown spots indicating CRF- and TH-immunopositive cells were observed in the hypothalamus and LC. The differences of brightness and contrast among raw images were not adjusted to exclude any possibility of subjective selection of the immunoreactive cells.

Fig. 1. Effects of CTN administration on the mean number of corticotrophin- releasing factor (CRF) expression in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus. Representative photographs and the relative percentage values are indicated in (A) and (B), respectively. **p<0.01 vs. SAL group, #p<0.05 vs. CORT group.

Fig. 2. Effects of CTN administration on the mean number of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) expression in the locus coeruleus (LC). Representative photographs and the relative percentage values are indicated in (A) and (B), respectively. **p<0.01 vs. SAL group; #p<0.05 vs. CORT group.

Statistical analysis

All measurements were performed by an independent investigator blinded to the experimental conditions. Results in figures are expressed as mean ± standard error of means (SE). Differences within or between normally distributed data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS (Version 13.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

For statistical analysis of body weight gain was assessed using a one-way ANOVA with a repeated-measure factor of sessions (number of days) followed by the appropriate Tukey’s post-hoc analysis. Behavioral data, immunohistochemical data and CORT concentration analysis were also analyzed by oneway ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test.

RESULTS

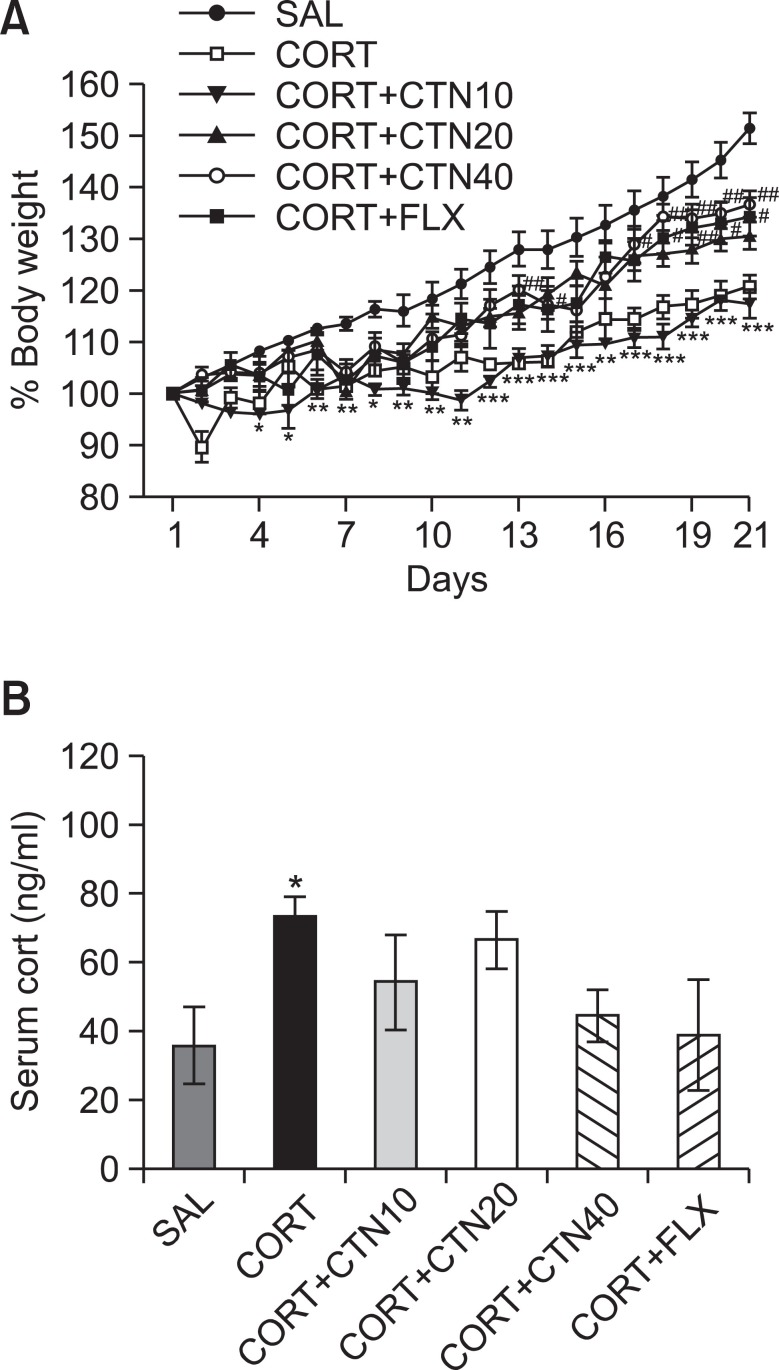

Effects of CTN on CORT-induced body weight loss and increase of serum CORT levels

Rats exposed to the repeated administration of exogenous CORT begin to lose body weight on the first day of CORT injections and this body weight loss is sustained for a prolonged period of time without restoration and is even exacerbated in some cases (Lee et al., 2012). In the present study, body weight was evaluated daily for 21 days to identify whether the repeated administration of CORT (CORT group) would result in body weight loss (difference between daily weights and starting weight; Fig. 3A). Analysis of the body weight values revealed a significant gradual reduction of body weight gain over 21 days in the CORT group relative to control rats (SAL group). During this period, rats treated with 20 or 40 mg/kg CTN exhibited a significant inhibition of the reduction in body weight gain compared to the CORT group (p<0.05 on day 14 in the CORT+CTN20 group; p<0.01 on days 13, 17, 18, 19, 20 and 21 in the CORT+CTN40 group).

Fig. 3. Effects of CTN administration on body weights gain (A) and blood levels of corticosterone (B) of the rats under chronic CORT injection for 21 consecutive days. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. SAL group, #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 vs. CORT group.

Additionally, the serum CORT levels were measured in each group following the repeated administration of CORT for 21 days. ELISA analysis revealed that CORT administration over 21 days significantly increased serum CORT concentrations by 205% compared to saline-treated rats (Fig. 3B; p<0.05). This indicates that repeated CORT injections were sufficiently stressful despite the evoked CORT response (physiological response) to repeated CORT injections being significantly greater than the response to a single CORT injection (data not shown). In these results, the exogenous CORT-induced depression-like symptoms were exploited to develop a chronic stress model in rats. Daily administration of CTN slightly inhibited the exogenous CORT-induced increase of serum CORT levels compared to the CORT group, although the findings were only minimally significance.

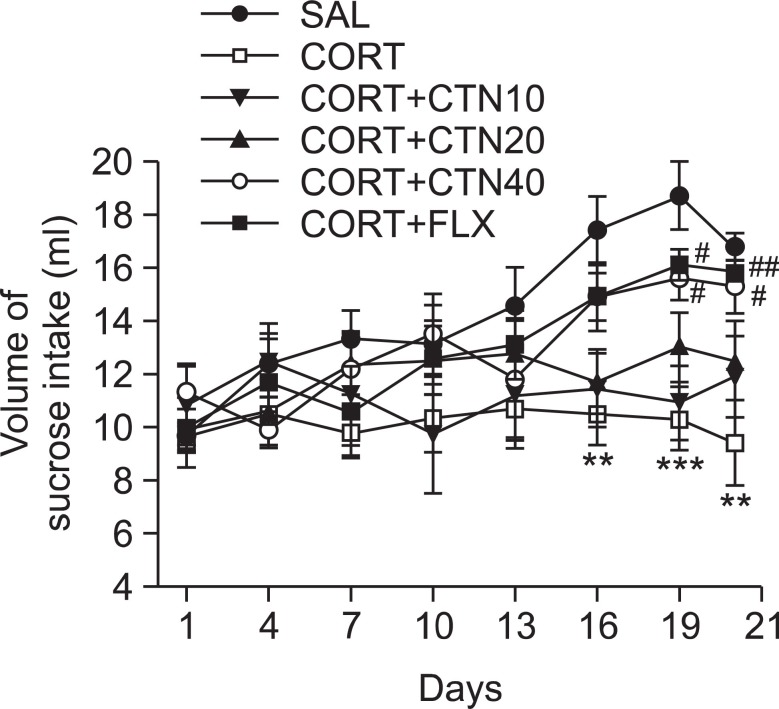

Effects of CTN on CORT-induced reductions in consumed sucrose intake

In the present study, sucrose intake was examined once every three days over 21 days to identify whether the repeated administration of CORT resulted in differences in the consumption of a sucrose solution compared to saline-treated rats (Fig. 4). The analysis of sucrose intake revealed a significant gradual reduction in consumed sucrose intake over 21 days in the CORT group compared to the SAL group (p<0.01 on days 16 and 21; p<0.001 on day 19). During this period, rats treated with 40 mg/kg of CTN exhibited a significant inhibition of the reduction in consumed sucrose intake compared to the CORT group (p<0.05 on days 19 and 21).

Fig. 4. Effects of CTN administration on sucrose intake of the rats under chronic CORT injection for 21 consecutive days. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. SAL group, #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 vs. CORT group.

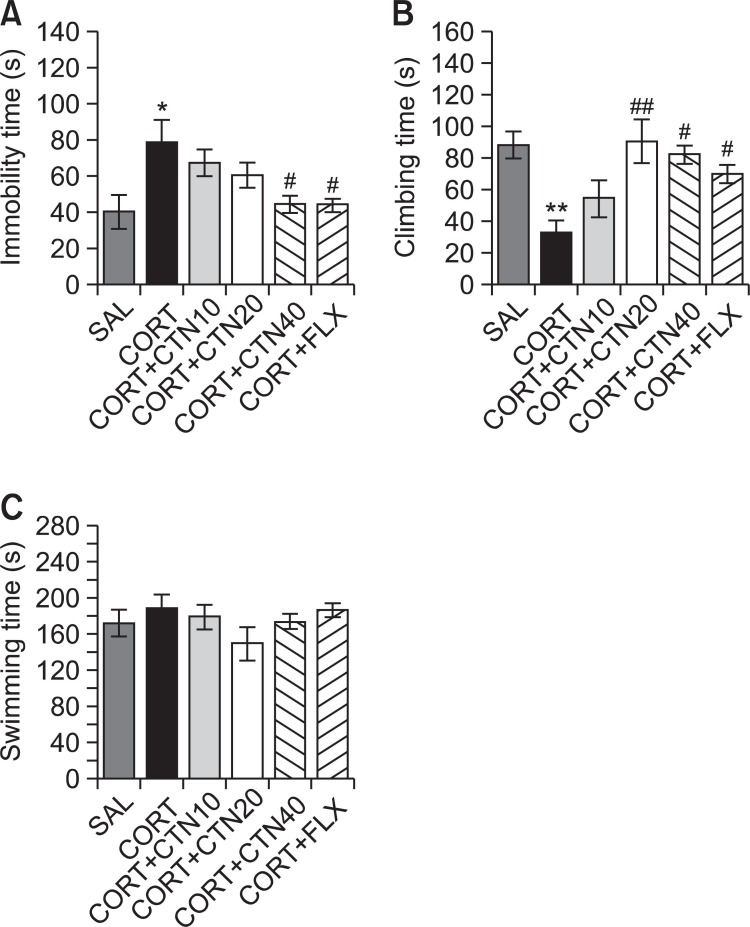

Effects of CTN on CORT-induced depression-like behaviors

Rats subjected to the repeated administration of exogenous CORT for 21 days exhibited a significant depression-like phenotype, characterized by increased an increased duration of immobility during the FST compared to saline-treated controls (Fig. 5). Rats in the CORT group exhibited more immobility during the FST compared to the SAL group (p<0.05; Fig. 5A). However, rats in the CORT+CTN40 group displayed a significant decrease in durations of immobility during 5 min in the FST compared to CORT group (p<0.05), indicating that the administration of 40 of mg/kg CTN decreases depressionlike behaviors. Another key behavior, climbing behavior was also analyzed. Rats in the CORT group exhibited a significant decrease in climbing behavior during the FST relative to the SAL group (p<0.01; Fig. 5B). Furthermore, compared with the CORT group, rats in the CORT+CTN20 (p<0.01) and CORT+CTN40 (p<0.05) groups exhibited a significant restoration of climbing behavior time during 5 min in the FST. This indicates that CORT administration significantly restores depression-like despair behaviors. However, repeated administration of exogenous CORT over 21 days did not induce significant differences in swimming behaviors among the groups during the FST (Fig. 5C). These results reveal that the recovery of climbing behavior and the reduction in immobility during depression-like behaviors in the CORT+CTN40 group was almost comparable to those of the CORT+FLX group.

Fig. 5. Effects of CTN administration on immobility time (A), climbing behavior (B) and swimming behavior (C) in forced swimming test during chronic CORT injection. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. SAL group; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 vs. CORT group.

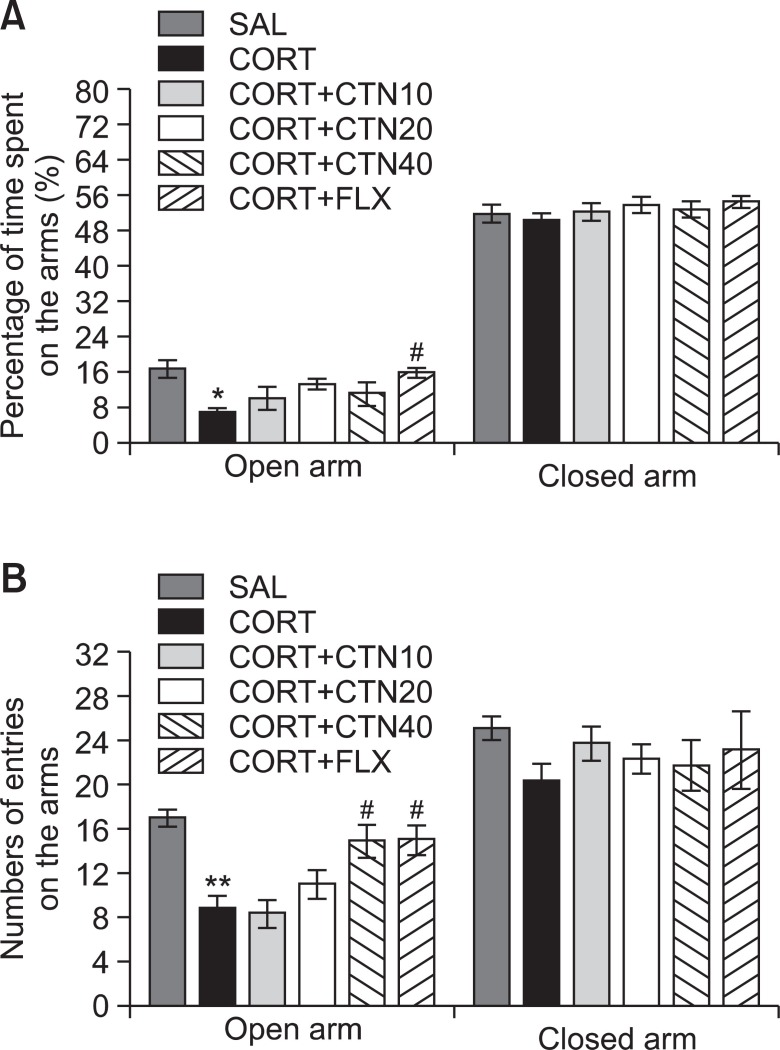

Effects of CTN on CORT-induced anxiety-like behaviors

The effects of CTN administration on anxiety-like behaviors, characterized by decreases in open-arm exploration in the EPM test, were also investigated (Fig. 6). Post-hoc comparisons revealed a significant decrease in the percentage of time spent by rats in the open arms of the maze following the repeated administration of exogenous CORT for 21 days compared to the saline-treated rats (p<0.05). However, compared to the CORT group, rats in the CORT+CTN40 group exhibited a slightly increased restoration of the percentage of time spent in open arms of the maze, which was formerly decreased by CORT-induced anxiety-like behaviors, although the findings were only minimally significant (Fig. 6A). Similarly, post hoc comparisons revealed a significant decrease in the number of entries into the open arms of the maze after the repeated administration of exogenous CORT for 21 days compared to the SAL group (p<0.01). Rats in the CORT+CTN40 group also exhibited a significant restoration in the number of entries into the open arms of the maze compared to the CORT group (p<0.05; Fig. 6B). Because no significant differences appeared in the number of closed-arm entries between groups in the EPM test, the observed anxiety-like behaviors of the rats receiving repeated CORT injections are likely not attributable to differences in their locomotor activities (Fig. 6B). CTN administration without the prior repeated administration of exogenous CORT did not elicit anxiolytic or anxiogenic behavior in this study. These results reveal that the increase in the number of entries into the open arms of the maze by the CORT+CTN40 group was almost comparable to those of the CORT+FLX group.

Fig. 6. Effects of CTN administration on the percentage of time spent on open and closed arms (A) and the numbers of entries into open and closed arms (B) in the elevated plus maze during chronic CORT injection. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. SAL group, #p<0.05 vs. CORT group.

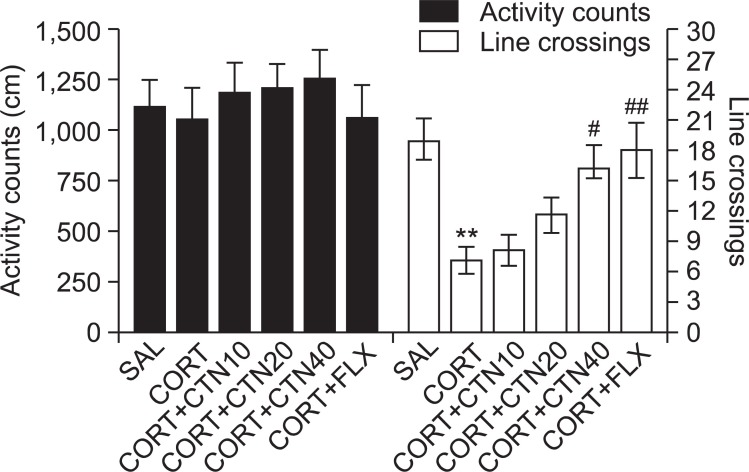

Effects of CTN on CORT-induced motor functions or exploratory behaviors

Open-field activity was used to evaluate locomotor activity and exploratory behavior among the rats receiving CORT injections for 21 days (Fig. 7). No significant differences appeared in locomotor activity (motor function) in the open-field test among groups. However, rats receiving CORT injections displayed a significant decrease in the total number of line crossings compared to the SAL group (p<0.01). This finding suggests that CORT-treated rats subsequently produce exploration activities that are closely associated with anxiety-like behaviors in the open-field test. However, CTN-treated rats (40 mg/kg) displayed a significant increase in the total number of line crossings compared to the CORT group (p<0.05), indicating that anxiety-like behaviors in the CORT+CTN40 group was almost comparable to those of the CORT+FLX group.

Fig. 7. Effects of CTN administration on activity counts of locomotor activity and total number of line crossing in the open-field test during chronic CORT injection. **p<0.01 vs. SAL group, #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 vs. CORT group.

Effects of CTN on CORT-induced CRF- and TH-like immunoreactivities

Following the behavioral tasks, CRF-like immunoreactivity was analyzed in the cell bodies of various hypothalamic regions including the paraventricular nucleus (PVN; Fig. 1A). The numbers of CRF-immunoreactive fibers in the PVN of the CORT group were increased by 207%. Analysis of the numbers of CRF-immunoreactive neurons values revealed that rats receiving repeated administration of exogenous CORT exhibited a significant increase of CRF expression compared to the SAL group (p<0.01; Fig. 1B). The number of CRF-immunoreactive neurons was significantly decreased in the PVN region of the CORT+CTN40 group compared to the CORT group (p<0.05). This finding suggests that the increased CRF-immunoreactivity induced by the repeated administration of exogenous CORT was significantly restored by CTN administration and that the number of CRF-immunopositive neurons in the CORT+CTN40 group was closely associated with that in the CORT+FLX group (p<0.05). TH-like immunoreactivity was also analyzed in adrenergic regions including the LC (Fig. 2A). The numbers of TH-immunoreactive fibers in the LC of the CORT group increased to 168%. Analysis of the numbers of TH-immunoreactive neurons values revealed that rats repeatedly exposed to exogenous CORT exhibit a significant increase of TH expression compared to the SAL group (p<0.01; Fig. 2B). The number of TH-immunoreactive neurons significantly decreased in central adrenergic regions of the CORT+CTN40 group relative to the CORT group (p<0.05). This finding indicates that the increase in the number of TH-immunoreactive neurons in rats repeatedly treated with exogenous CORT was significantly restored by CTN administration.

DISCUSSION

These results clearly demonstrate that the repeated administration of CTN prior to CORT injection significantly decreases the duration of immobility in the FST and increases open-arm exploration in the EPM. It is likely that these behavioral effects are based on a modulation of hypothalamic CRF activity and the noradrenergic system within the central nervous system. Thus, the current results support the possibility that CTN has antidepressant and anxiolytic effects. The dose-dependent activity of CTN (10, 20, or 40 mg/kg) was examined, and a dose of 40 mg/kg was the most effective in inhibiting chronic CORT-induced harmful effects in the FST and EPM tests, which include depression- and anxiety-like behavior. The optimum dose determined in this study has been shown in a previous study (Ashafaq et al., 2012).

Previous studies on the emotional effects of chronic CORT injections in rodents have produced controversial results (Roozendaal et al., 2006). Several reports have demonstrated that administration of the exogenous stress hormone CORT increases the probability of depression-like behavior, which is consistent with the present results (Lee et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2011). In addition, when measured immediately after behavioral testing, a gradual decrease in body weight gain and an increase in serum CORT levels was observed indicating that the chronic CORT injections were sufficiently stressful (Lee et al., 2012). Many studies have been shown that chronic administration of high-dose CORT increased serum CORT concentrations in the rats, in line with chronic stress models (Wüppen et al., 2010). Accordingly, in animal models, forced sustaining of high CORT levels can affect animal depressionlike symptom under experimental conditions, and this might be closely associated with the progression or exacerbation of chronically stressful conditions in humans (Wüppen et al., 2010). The administration of CTN significantly restored body weight and decreased the serum CORT levels in the late period of CTN administration, suggesting that this therapy inhibited the HPA axis-associated psychological dysfunction induced by repeated CORT injections. Our results may help to explain that administration of CTN may affect the hypothalamus to received biochemical and behavioral signals induced by reduced CORT level in serum. Thus, it can be suggested that the administration of CTN may modulate the dysregulation of HPA axis, which means administration of CTN could influence endogenous CORT levels in the CNS, thereby normalizing behavioral and neurochemical response. The reductions in behavioral activity and sucrose consumption, which are typically observed in depression, might be due to a dysregulation of the HPA axis following the artificial injection of CORT (Sigwalt et al., 2011). This theory has been supported by several studies in which elevated levels of CORT result in an alteration of HPA axis activity that affects behavioral activity and sucrose consumption (Liu et al., 2012). The administration of CTN prior to CORT injection also increased sucrose consumption, as compared to rats in the CORT-treated control group, suggesting that the administration of CTN counteracts chronic CORT-induced depressive symptoms.

Furthermore, the current results are consistent with previous findings showing that repeated CORT injections decrease immobility during the FST (Yi et al., 2012). Here, the administration of CTN significantly decreased immobility and also increased climbing behaviors during the FST but there was no effect on swimming, which confirms an antidepressant-like activity that does not result in deficits in motor function (Lee et al., 2009; Yi et al., 2012). The FST is a valuable and reliable behavioral research model of depression in rodents and is also an important tool with which to study the neurobiological mechanisms involved in antidepressant responses (Cryan and Holmes, 2005). The observed immobility behavior in the FST is similar to a state of lowered mood or helplessness and may be considered analogous to depression in humans (Cryan and Holmes, 2005). Although the FST provides information about mood (i.e., depression) in rodents, it is important to use caution when extrapolating the data to humans (Anisman and Matheson, 2005). Nonetheless, these data support the possibility that CTN might have antidepressant effects.

Anxiety is another complex feature of depression and the presence of anxiety-like symptoms in chronically stressed animals should not be surprising. Many studies have suggested that stressed rats show decreases in the proportion of time spent and number of entries into the open arms of the EPM compared with a non-stressed normal control (Waters and McCormick, 2011). Although the EPM test is based on an aversive context, conflict, and the subsequent movement of an animal between an open and illuminated environment, the test includes two additional anxiety-provoking environmental parameters; height and open area (Fan et al., 2009). In the present study, the administration of CTN prior to chronic CORT injections significantly reduces anxiety-like behaviors in the EPM test, as indicated by an increase in the number of entries in open arms. Thus, these results suggest that CTN has anxiolytic activity (Waters and McCormick, 2011).

An open-field test was also performed to rule out any confounding motor impairments that can influence outcomes in many behavioral tests of depression or anxiety (Kokras et al., 2012). No significant individual differences in locomotor activity were observed between groups, suggesting that the administration of CTN had no effect on sensorimotor performance. However, the administration of CTN prior to chronic CORT injections significantly reduces anxiety-like behaviors, as indicated by an increase in total number of line crossing in open-field test. Accordingly, these results suggest that the observed increase of total number of line crossing in open-field test is similar to observed changes in behavioral performance in the EPM test, which these results were likely due to anxiolytic activity.

Previous studies have shown that the hypothalamic CRF system is involved in the regulation of HPA axis hyperactivity as well as the depression- and anxiety-like behaviors induced by chronic CORT injections (Sevgi et al., 2006). The current data suggest that the CRF circuits in the PVN of the hypothalamus are activated by chronic CORT injections, which lead to the observed depressive- and anxiety-like activity in the behavioral tests (Lee et al., 2009). These results show that the administration of CTN significantly blocks the increase in CRF immunoreactivity in the PVN. It is thought that hypothalamic CRF then suppresses depression- and anxiety-like behaviors by inducing the production of peripheral antidepressive and anxiolytic mediators from central sites in the PVN within the hypothalamus (Surget et al., 2008). This suggests that antidepressive and anxiolytic effects following the administration of CTN are closely associated with CRF modulation in the PVN in the hypothalamus and activation of the HPA axis.

In the present study, TH immunoreactivity in the LC in response to repeated CORT injections was greater in the CORT group relative to the SAL group. These results are consistent with previous reports that depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors induced by chronic stress are the result of alterations in the central noradrenergic system (Sevgi et al., 2006). Moreover, these findings demonstrate that the administration of CTN significantly reduces TH-like immunoreactivity in the LC that was previously activated by chronic CORT injections. TH is an enzyme involved in the stress-induced activation of the central nervous system and stress-related psychopathological conditions such as depression and anxiety (MacGillivray et al., 2011). The ascending noradrenergic neurotransmitter system that primarily originates in the A6 noradrenergic neurons of the LC is a major circuit in the central nervous system involved in the stress response (Osterhout et al., 2005). Thus, these results suggest that administration of CTN might indirectly alter catecholamine synthesis in the brain to produce pharmacological effects (Spasojevic et al., 2010). This would mean that CTN acts by inhibiting noradrenaline synthesis in the rat brain and raises the possibility that an overactive noradrenergic system could contribute to depressive symptomology as well as the fact that the therapeutic action of antidepressants reverses such overactivity via a decrease of TH expression in the LC (Park et al., 2010). Some studies have reported that immobility and climbing behavior during the FST are associated with central noradrenergic system activity (Tanaka and Telegdy, 2008). Activation of TH in the LC produces depression, intense anxiety, and the inhibition of exploratory behavior (Park et al., 2010). It has been proposed that clinical depression or anxiety may be the result of alterations of TH activity within the central noradrenergic system (Park et al., 2010). Thus, the current results suggest that the central noradrenergic system was involved in the antidepressant effect of CTN on helpless-like behavior that persists for 21 days in rats administered repeated CORT injections. Therefore, based on the present observations, a hypothesis concerning the mechanisms underlying the behavioral effects of CTN can be proposed in which the depression- and anxiety-induced behaviors occur via a dysregulation of the HPA axis and the neurochemical interactions between CRF and TH in the brain.

It is also necessary to be aware that other types of CTN and even other classes of green tea components may be beneficial to psychosomatic diseases such as depression and anxiety. For example, the potentially beneficial effects of green tea are attributed to CTN compounds, particularly EGCG, which is the most abundant and extensively studied CTN compound of green tea (Baluchnejadmojarad and Roghani, 2011). The effective dose of CTN remains to be elucidated, as do whether there are any beneficial effects of fortified foods or supplements (Lin et al., 2010).

In summary, the present study demonstrates that chronic CORT injections significantly increases the duration of immobility in the FST and decreases open-arm exploration in the EPM test compared with unstressed normal controls. Furthermore, the administration of CTN significantly reduces depression- and anxiety-like symptom following repeated administration of the exogenous stress hormone CORT, possibly via modulation of hypothalamic CRF and the central noradrenergic system. Together, these findings indicate that CTN is capable of ameliorating the complex behaviors and neurochemical responses involved in depression by modulating HPA activity. Accordingly, CTN may be a useful therapeutic agent in the development of alternative medicines for treating stress-related disorders such as depression and anxiety.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (MEST)(2010-0003678) and by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (No. 2005-0049404).

References

- 1.Ago Y., Yano K., Araki R., Hiramatsu N., Kita Y., Kawasaki T., Onoe H., Chaki S., Nakazato A., Hashimoto H., Baba A., Takuma K., Matsuda T. Metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor antagonists improve behavioral and prefrontal dopaminergic alterations in the chronic corticosterone-induced depression model in mice. Neuropharmacology. (2013);65:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aina Y., Susman J. L. Understanding comorbidity with depression and anxiety disorders. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. (2006);106:S9–S14. Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anisman H., Matheson K. Stress, depression, and anhedonia: Caveats concerning animal models. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. (2005);29:525–546. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashafaq M., Raza S. S., Khan M. M., Ahmad A., Javed H., Ahmad M. E., Tabassum R., Islam F., Siddiqui M. S., Safhi M. M., Islam F. Catechin hydrate ameliorates redox imbalance and limits inflammatory response in focal cerebral ischemia. Neurochem. Res. (2012);37:1747–1760. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0786-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baluchnejadmojarad T., Roghani M. Chronic epigallocatechin- 3-gallate ameliorates learning and memory deficits in diabetic rats via modulation of nitric oxide and oxidative stress. Behav. Brain Res. (2011);224:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burckhardt I. C., Gozal D., Dayyat E., Cheng Y., Li R. C., Goldbart A. D., Row B. W. Green tea catechin polyphenols attenuate behavioral and oxidative responses to intermittent hypoxia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. (2008);177:1135–1141. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-110OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W. Q., Zhao X. L., Wang D. L., Li S. T., Hou Y., Hong Y., Cheng Y. Y. Effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate on behavioral impairments induced by psychological stress in rats. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). (2010);235:577–583. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.009329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cryan J. F., Holmes A. The ascent of mouse: advances in modelling human depression and anxiety. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. (2005);4:775–790. doi: 10.1038/nrd1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dal Belo S. E., Gaspar L. R., Maia Campos P. M. Photoprotective effects of topical formulations containing a combination of Ginkgo biloba and green tea extracts. Phytother. Res. (2011);25:1854–1860. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dazzi L., Seu E., Cherchi G., Biggio G. Chronic administration of the SSRI fluvoxamine markedly and selectively reduces the sensitivity of cortical serotonergic neurons to footshock stress. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. (2005);15:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deligiannidis K. M., Freeman M. P. Complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of depressive disorders in women. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. (2010);33:441–463. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans J., Sun Y., McGregor A., Connor B. Allopregnanolone regulates neurogenesis and depressive/anxiety-like behaviour in a social isolation rodent model of chronic stress. Neuropharmacology. (2012);63:1315–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan J. M., Chen X. O., Jin H., Du J. Z. Gestational hypoxia alone or combined with restraint sensitizes the hypothalamic- pituitary-adrenal axis and induces anxiety-like behavior in adult male rat offspring. Neuroscience. (2009);159:1363–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregus A., Wintink A. J., Davis A. C., Kalynchuk L. E. Effect of repeated corticosterone injections and restraint stress on anxiety and depression-like behavior in male rats. Behav. Brain Res. (2005);156:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill M. N., Hellemans K. G., Verma P., Gorzalka B. B., Weinberg J. Neurobiology of chronic mild stress: parallels to major depression. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. (2012);36:2085–2117. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Z., Zhong X. M., Li Z. Y., Feng C. R., Pan A. J., Mao Q. Q. Curcumin reverses corticosterone-induced depressivelike behavior and decrease in brain BDNF levels in rats. Neurosci. Lett. (2011);493:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kokras N., Dalla C., Sideris A. C., Dendi A., Mikail H. G., Antoniou K., Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z. Behavioral sexual dimorphism in models of anxiety and depression due to changes in HPA axis activity. Neuropharmacology. (2012);62:436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kutiyanawalla A., Terry A. V., Jr. Pillai A. Cysteamine attenuates the decreases in TrkB protein levels and the anxiety/depression-like behaviors in mice induced by corticosterone treatment. PLoS One. (2011);6:e26153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon S., Lee B., Kim M., Lee H., Park H. J., Hahm D. H. Antidepressant-like effect of the methanolic extract from Bupleurum falcatum in the tail suspension test. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol Biol. Psychiatry. (2010);34:265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee B., Shim I., Lee H. J., Yang Y., Hahm D. H. Effects of acupuncture on chronic corticosterone-induced depression-like behavior and expression of neuropeptide Y in the rats. Neurosci. Lett. (2009);453:15–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee B., Sur B. J., Kwon S., Jung E., Shim I., Lee H., Hahm D. H. Acupuncture stimulation alleviates corticosteroneinduced impairments of spatial memory and cholinergic neurons in rats. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. (2012);2012:670536. doi: 10.1155/2012/670536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Q., Zhao H. F., Zhang Z. F., Liu Z. G., Pei X. R., Wang J. B., Li Y. Long-term green tea catechin administration prevents spatial learning and memory impairment in senescance-accelerated mouse prone-8 mice by decreasing Abeta1-42 oligomers and upregulating synaptic plasticity-related proteins in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. (2009);163:741–749. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liebert R., Gavey N. There are always two sides to these things: managing the dilemma of serious adverse effects from SSRIs. Soc. Sci. Med. (2009);68:1882–1891. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin S. M., Wang S. W., Ho S. C., Tang Y. L. Protective effect of green tea (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate against the monoamine oxidase B enzyme activity increase in adult rat brains. Nutrition. (2010);26:1195–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu W., Xu Y., Lu J., Zhang Y., Sheng H., Ni X. Swimming exercise ameliorates depression-like behaviors induced by prenatal exposure to glucocorticoids in rats. Neurosci. Lett. (2012);524:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacGillivray L., Reynolds K. B., Sickand M., Rosebush P. I., Mazurek M. F. Inhibition of the serotonin transporter induces microglial activation and downregulation of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. Synapse. (2011);65:1166–1172. doi: 10.1002/syn.20954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackenzie C. S., Reynolds K., Cairney J., Streiner D. L., Sareen J. Disorder-specific mental health service use for mood and anxiety disorders: associations with age, sex, and psychiatric comorbidity. Depress. Anxiety. (2012);29:234–242. doi: 10.1002/da.20911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandel S., Amit T., Reznichenko L., Weinreb O., Youdim M. B. Green tea catechins as brain-permeable, natural iron chelators- antioxidants for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. (2006);50:229–234. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500156. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLaughlin K. J., Gomez J. L., Baran S. E., Conrad C. D. The effects of chronic stress on hippocampal morphology and function: an evaluation of chronic restraint paradigms. Brain Res. (2007);1161:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molina-Hernández M., Téllez-Alcántara N. P., Olivera-López J. I., Jaramillo M. T. Intra-lateral septal infusions of folic acid alone or combined with various antidepressant drugs produce antidepressant- like actions in male Wistar rats forced to swim. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. (2012);36:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niu K., Hozawa A., Kuriyama S., Ebihara S., Guo H., Nakaya N., Ohmori-Matsuda K., Takahashi H., Masamune Y., Asada M., Sasaki S., Arai H., Awata S., Nagatomi R., Tsuji I. Green tea consumption is associated with depressive symptoms in the elderly. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. (2009);90:1615–1622. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osterhout C. A., Sterling C. R., Chikaraishi D. M., Tank A. W. Induction of tyrosine hydroxylase in the locus coeruleus of transgenic mice in response to stress or nicotine treatment: lack of activation of tyrosine hydroxylase promoter activity. J. Neurochem. (2005);94:731–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park H. J., Shim H. S., Kim H., Kim K. S., Lee H., Hahm D. H., Shim I. Effects of Glycyrrhizae Radix on repeated restraint stress-induced neurochemical and behavioral responses. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. (2010);14:371–376. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2010.14.6.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paxinos G., Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press.; New York: (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roozendaal B., Hui G. K., Hui I. R., Berlau D. J., McGaugh J. L., Weinberger N. M. Basolateral amygdala noradrenergic activity mediates corticosterone-induced enhancement of auditory fear conditioning. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. (2006);86:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sevgi S., Ozek M., Eroglu L. L-NAME prevents anxietylike and depression-like behavior in rats exposed to restraint stress. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. (2006);28:95–99. doi: 10.1358/mf.2006.28.2.977840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sigwalt A. R., Budde H., Helmich I., Glaser V., Ghisoni K., Lanza S., Cadore E. L., Lhullier F. L., de Bem A. F., Hohl A., de Matos F. J., de Oliveira P. A., Prediger R. D., Guglielmo L. G., Latini A. Molecular aspects involved in swimming exercise training reducing anhedonia in a rat model of depression. Neuroscience. (2011);192:661–674. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spasojevic N., Gavrilovic L., Dronjak S. Effects of repeated maprotiline and fluoxetine treatment on gene expression of catecholamine synthesizing enzymes in adrenal medulla of unstressed and stressed rats. Auton. Autacoid Pharmacol. (2010);30:213–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.2010.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steiner M. A., Marsicano G., Nestler E. J., Holsboer F., Lutz B., Wotjak C. T. Antidepressant-like behavioral effects of impaired cannabinoid receptor type 1 signaling coincide with exaggerated corticosterone secretion in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2008);33:54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Surget A., Saxe M., Leman S., Ibarguen-Vargas Y., Chalon S., Griebel G., Hen R., Belzung C. Drug-dependent requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis in a model of depression and of antidepressant reversal. Biol. Psychiatry. (2008);64:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka T., Miyata Y., Tamaya K., Kusano R., Matsuo Y., Tamaru S., Tanaka K., Matsui T., Maeda M., Kouno I. Increase of theaflavin gallates and thearubigins by acceleration of catechin oxidation in a new fermented tea product obtained by the tea-rolling processing of loquat (Eriobotrya japonica) and green tea leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. (2009);57:5816–5822. doi: 10.1021/jf900963p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka M., Telegdy G. Involvement of adrenergic and serotonergic receptors in antidepressant-like effect of urocortin 3 in a modified forced swimming test in mice. Brain Res. Bull. (2008);77:301–305. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torres I. L., Gamaro G. D., Vasconcellos A. P., Silveira R., Dalmaz C. Effects of chronic restraint stress on feeding behavior and on monoamine levels in different brain structures in rats. Neurochem. Res. (2002);27:519–525. doi: 10.1023/A:1019856821430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uliaszek A. A., Zinbarg R. E., Mineka S., Craske M. G., Sutton J. M., Griffith J. W., Rose R., Waters A., Hammen C. The role of neuroticism and extraversion in the stress-anxiety and stress-depression relationships. Anxiety Stress Coping. (2010);23:363–381. doi: 10.1080/10615800903377264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waters P., McCormick C. M. Caveats of chronic exogenous corticosterone treatments in adolescent rats and effects on anxiety-like and depressive behavior and hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal (HPA) axis function. Biol. Mood Anxiety Disord. (2011);1:4. doi: 10.1186/2045-5380-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wüppen K., Oesterle D., Lewicka S., Kopitz J., Plaschke K. A subchronic application period of glucocorticoids leads to rat cognitive dysfunction whereas physostigmine induces a mild neuroprotection. J. Neural Transm. (2010);117:1055–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yi L. T., Li J., Li H. C., Zhou Y., Su B. F., Yang K. F., Jiang M., Zhang Y. T. Ethanol extracts from Hemerocallis citrina attenuate the decreases of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, TrkB levels in rat induced by corticosterone administration. J. Ethnopharmacol. (2012);144:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yilmaz Y., Toledo R. T. Major flavonoids in grape seeds and skins: antioxidant capacity of catechin, epicatechin, and gallic acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. (2004);52:255–260. doi: 10.1021/jf030117h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu W. L., Shi H. S., Wei Y. M., Wang S. J., Sun C. Y., Ding Z. B., Lu L. Green tea polyphenols produce antidepressantlike effects in adult mice. Pharmacol. Res. (2012);65:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]