Summary

Natural transformation is a major mechanism of horizontal gene transfer in bacteria. By incorporating exogenous DNA elements into chromosomes, bacteria are able to acquire new traits that can enhance their fitness in different environments. Within the past decade, numerous studies have revealed that natural transformation is prevalent among members of the Vibrionaceae, including the pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Four environmental factors, i) nutrient limitation, ii) availability of extracellular nucleosides, iii) high cell density, and iv) the presence of chitin, promote genetic competence and natural transformation in Vibrio cholerae by coordinating expression of the regulators CRP, CytR, HapR, and TfoX, respectively. Studies of other Vibrionaceae members highlight the general importance of natural transformation within this bacterial family.

Introduction

Many bacterial species can become competent to take up environmental DNA. While DNA transported across the cytoplasmic membrane by the competence machinery may serve as a source of nutrients or as a template for repairing chromosomal damage, it can also be incorporated onto the chromosome by homologous recombination. This latter phenomenon, referred to as natural transformation, is a prime example of horizontal gene transfer, which, along with conjugation and transduction, can result in the emergence of new traits (Chen et al., 2005). Recently, various members of the Vibrionaceae family have been shown to be naturally competent to take up DNA.

The Vibrionaceae family consists of a remarkably diverse set of Gram-negative bacteria. In general, Vibrionaceae members are readily isolated from aqueous environments ranging from freshwater to marine conditions and are easily cultured. Pathogenic Vibrionaceae members, particularly Vibrio cholerae, have significantly impacted human health, both historically and currently, and, as a result, have garnered a great deal of attention from the biomedical community (Piarroux and Faucher, 2012; Marin et al., 2013). However, numerous ecological studies of this diverse family of bacteria have revealed that they often form non-pathogenic, and in many cases beneficial relationships with eukaryotes (Huq et al., 1983; Visick and Ruby, 2006; Senderovich et al., 2010).

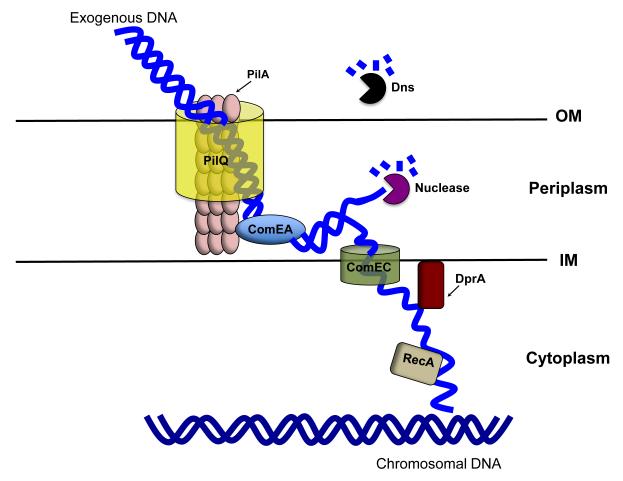

Many features of the competence machinery and its regulation in Vibrionaceae members are similar to those of archetypical systems described for Gram-negative bacteria. In general, uptake of environmental DNA requires a complex apparatus that first binds the DNA at the cell surface and then delivers it through the membrane to the cytoplasm (Dubnau, 1999; Seitz and Blokesch, 2013). In Neisseria species, such as Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the outer membrane secretin pore PilQ allows double-stranded DNA to enter into the periplasm (Lång et al., 2009). With the help of a pseudo-pilus encoded in part by pilE, the periplasmic protein ComEA binds the DNA and directs it to the inner-membrane channel ComEC (Fig. 1, Wolfgang et al., 2002). The minor pilin ComP also contributes to natural transformation by serving as a DNA receptor that recognizes species-specific DNA uptake sequences (DUS) (Aas et al., 2002; Cehovin et al., 2013). One strand of the DNA enters the cytoplasm through ComEC, while the complement strand is degraded (Fig. 1, Chen et al., 2005). Once inside the cytoplasm, this DNA may be integrated into the chromosome through homologous recombination (Fig. 1). In Haemophilus influenzae, another Gram-negative bacterium that serves as a model system for natural transformation, the secretin that allows the entry of double-stranded DNA is called ComE; the crucial subunit of the pseudo-pilus involved in DNA uptake is PilA; and the counterparts of ComEA and ComEC are ComE1 and Rec2, respectively (Chen and Dubnau, 2004; Mell et al., 2012; MacFadyen et al., 2001). Vibrionaceae members such as V. cholerae possess homologs of PilQ, PilA, ComEA and ComEC, which play crucial roles in the uptake of exogenous DNA (Fig. 1, Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2012). To our knowledge, no homologue of ComP has been reported for H. influence or members of the Vibrionaceae. In addition, for most Gram-negative bacteria, whether DNA uptake is achieved by a type IV pilus or a pseudo-pilus remains generally unknown.

Fig. 1. The natural transformation machinery in V. cholerae.

Double-stranded DNA enters the periplasm by means of the secretin pore PilQ located within the outer membrane. The pseudo-pilus (PilA represents a subunit) helps the DNA bind to the periplasmic protein ComEA, which directs the DNA to the inner-membrane channel ComEC. Other components of a type IV pili system (not shown) may contribute to this process, but their involvement in natural transformation remains unknown. The extracellular DNA that fails to enter the periplasm is degraded by extracellular deoxyribonuclease Dns. One strand of the DNA enters the cytoplasm through ComEC, while the complement strand is degraded. The internalized single-stranded DNA is shielded from nuclease attack by the DNA protecting protein DprA and incorporated into chromosome by the recombinase RecA. IM = inner membrane; OM = outer membrane.

While the primary components of the competence machinery are conserved among bacteria, the regulatory networks that govern their expression vary tremendously to accommodate differences in lifestyles. For instance, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Bacillus subtilis, which have served as model organisms for natural transformation in Gram-positive bacteria, use the cell-cell form of communication known as quorum sensing to regulate the expression of competence genes (Solomon and Grossman, 1996). In H. influenzae, nutrient deprivation, rather than quorum sensing, controls competence (Chandler, 1992; Dorocicz et al., 1993). Finally, both N. meningitidis and N. gonorrheae are constitutively competent (Biswas et al., 1977).

The complex regulatory network that controls competence in Vibrionaceae members exhibits some features that are reminiscent of the model systems listed above. We begin this MicroReview with a description of the environmental signals that stimulate the competence pathway in V. cholerae. We then describe the complex regulatory mechanisms that control TfoX, which is a critical transcription factor that controls competence in Vibrionaceae as well as in other bacteria. This MicroReview also highlights the numerous studies of natural transformation in Vibrionaceae members other than V. cholerae. Finally, we discuss the role of natural transformation and, more generally, that of horizontal gene transfer on the diversity of the Vibrionaceae family and their corresponding impacts on human health.

Environmental inputs

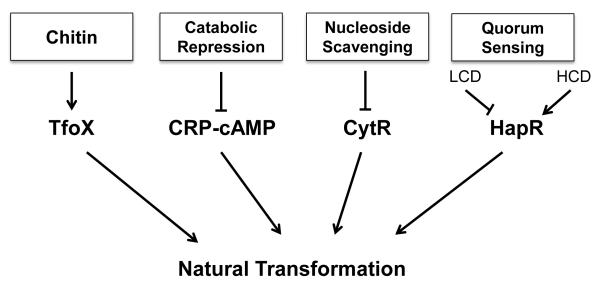

Numerous studies have shown that various environmental and physiological factors impact competence and natural transformation in V. cholerae (Meibom et al., 2005; Antonova and Hammer, 2011; Antonova et al., 2012; Blokesch, 2012; Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2012). The current model of the regulatory network governing competence in V. cholerae consists of four stimuli: chitin, quorum sensing, and the availability of carbon sources and extracellular nucleosides (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The current model of the regulatory network governing competence in V. cholerae.

The four known environmental stimuli are chitin, quorum sensing, and the availability of carbon sources and extracellular nucleosides. The model does not include information concerning crosstalk between signaling cascades. The lines connecting components of the signaling cascade do not indicate direct interaction. LCD = low cell density; HCD = high cell density.

Chitin

In 2005, it was first reported that V. cholerae becomes competent for natural transformation in the presence of chitin (Meibom et al., 2005). This result was independent of whether the chitin source was synthetically derived or in its natural state as crustacean exoskeletons (e.g., crab-shell tiles). To our knowledge, chitin has never been directly tested for its involvement in natural transformation in H. influenzae, N. gonorrheae or N. meningitidis (Biswas et al., 1977; Smith, 1980). However, given the absence of chitin in the natural habitats of these three bacterial species, chitin is unlikely to play any significant role in their transition to a genetically competent state.

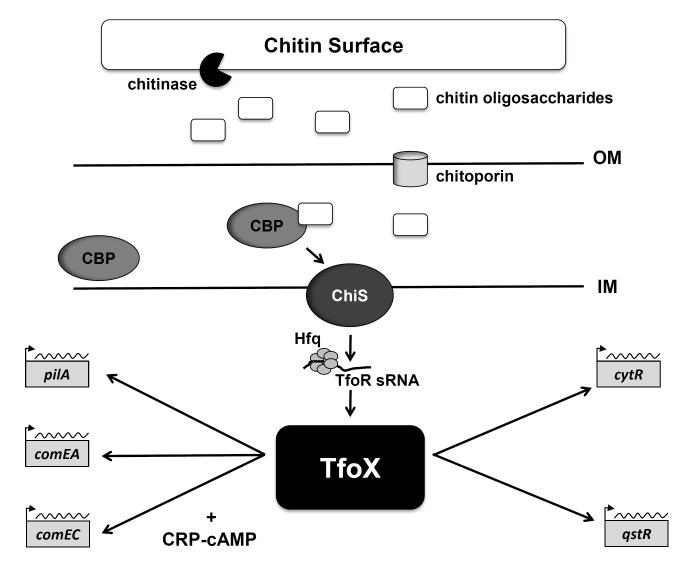

Chitin, which is composed of chains of β-1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residues, is the second most abundant biopolymer found in nature (Keyhani and Roseman, 1999; Hunt et al., 2008). Chitin can be found throughout all kingdoms, and its presence is widespread in marine environments, ranging from the cell walls of certain green algae to the exoskeletons of crustaceans (Keyhani and Roseman, 1999; Hunt et al., 2008). The majority of chitin in the aquatic biosphere is recycled by chitinolytic bacteria, including members of the Vibrionaceae family (Keyhani and Roseman, 1999; Meibom et al., 2004; Hunt et. al., 2008). Chitinolytic bacteria use chitin as a source of both carbon and nitrogen, through a complex process that involves the initial detection of chitin, attachment to a chitinaceous surface, and degradation of chitin (Keyhani and Roseman, 1999; Li and Roseman, 2004; Hunt and et al., 2008). By means of extracellular, secreted chitinases, chitin is cleaved into oligosaccharides fragments, (GlcNAc)n, which translocate into the periplasm and bind to a high-affinity, chitin oligosaccharide-binding protein (CBP) (Fig. 3). Binding of (GlcNAc)n to CBP activates a two-component sensor kinase named ChiS (Fig. 3). Signaling by ChiS, in turn, leads to production of chitinolytic enzymes, which break down (GlcNAc)n into monomers that are channeled into the central metabolism as fructose-6-phosphate, acetate and ammonium (Li and Roseman, 2004; Hunt et al., 2008). In addition to providing a source of carbon and nitrogen, chitin also influences many aspects of Vibrio physiology, including chemotaxis, biofilm formation, and pathogenicity (Amako et al., 1987; Bassler et al., 1989; Watnick et al., 1999; Kirn et al., 2005; Reguera and Kolter, 2005; Pruzzo et al., 2008; Mandel et al., 2012). Consistent with these effects on physiology, growth in chitin results in significant, global changes in gene expression (Meibom et al., 2004).

Fig. 3. Chitin-dependent signaling pathways for natural transformation in V. cholerae.

Chitin is degraded by extracellular chitinases into oligosaccharides fragments, which enter the periplasm through a chitoporin. With the help of CBP (chitin oligosaccharides binding protein), the sensor kinase ChiS senses the presence of chitin oligosaccharides and activates the TfoR sRNA. Via the RNA chaperone Hfq, TfoR initiates translation of TfoX, the master regulator of competence in Vibrionaceae. Consequently, TfoX up-regulates the expression of numerous competence genes (e.g., pilA, comEA and comEC) and of two genes encoding transcription factors (cytR and qstR). Regulation of the competence genes by TfoX also requires the cAMP-CRP complex. The lines connecting components of the signaling cascade represent positive regulation, but not direct interaction. IM = inner membrane; OM = outer membrane.

What is the role of chitin in activating the competence pathway in V. cholerae? One intriguing possibility is that chitin and its oligosaccharide derivatives signal the presence of a nearby host. Within this context, competent individuals may acquire from neighboring bacterial cells genetic elements for host interaction. In this manner, the chitin signal would result not only in enhanced genetic diversity but also the acquisition of host specificity factors. Consistent with this model, chitin is highly abundant in zooplankton and exoskeletons of shellfishes, which are two animal reservoirs that play crucial roles in transmission of V. cholerae (Sack et al., 2004). Another possibility is that chitin functions as a signal for Vibrionaceae to access an alternative nutrient source in particular environments, as previously implicated in the genetic competence-induction program in V. cholerae (Meibom et al., 2005). The resulting DNA uptake, in turn, may provide the Vibrionaceae members with an extra nutrient resource. Interestingly, chitin, which is crucial for natural transformation in V. cholerae (Meibom et al., 2005), is also one of the substrates on which V. cholerae develops biofilms (Watnick et al., 1999), which enable V. cholerae to survive stressful environments (Alam et al., 2007). In addition, exogenous DNA, which provides genetic material for natural transformation, is also prevalent in biofilm formation (Seper et al., 2011). Future studies that focus on chitin signaling in V. cholerae are required to elucidate its link to natural transformation.

Quorum Sensing

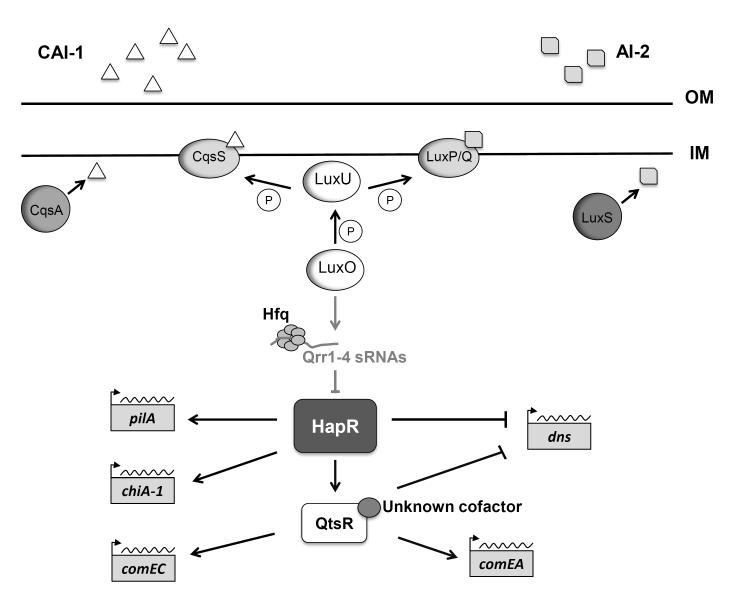

A second regulatory system controlling competence in V. cholerae is quorum sensing, which is a process of cell-cell communication that allows bacteria to coordinate gene expression according to population density (Ng and Bassler, 2009). All Vibrionaceae members produce and detect chemical signaling molecules called autoinducers (AIs). V. cholerae produces two AIs: CAI-1, which is restricted to certain Vibrionaceae members, and AI-2, an interspecies autoinducer produced by many bacteria (Bassler et al., 1997; Zhu and Mekalanos, 2003). At low cell density, i.e., when CAI-1 and AI-2 levels are low, their unbound cognate receptors CqsS and LuxP/Q complex, respectively, behave as kinases and initiate a phosphorylation cascade via LuxU that phosphorylates the response regulator LuxO (Fig. 4). Phosphorylated LuxO activates the transcription of four small RNAs, called Qrrs (quorum regulatory RNAs), which, via the RNA chaperone Hfq, post-transcriptionally repress HapR, the master regulator of quorum sensing (Lenz et al., 2004; Bardill et al., 2011; Bardill and Hammer, 2012). In contrast, at high cell density, when CAI-1 and AI-1 levels are high, binding of the AIs to their cognate receptors reverses the phosphate flow in the LuxU-LuxO phosphorelay, resulting in production of HapR. The role of HapR in controlling virulence and surface-attachment genes important in vivo during association with a human host has been well described (Zhu et al., 2002; Hammer and Bassler, 2003).

Fig. 4. Quorum sensing-dependent pathways for natural transformation in V. cholerae.

At high cell density (depicted here), CAI-1 and AI-2 autoinducers bind to their cognate histidine kinase receptors (CqsS and LuxP/Q, respectively), which shuttle phosphate from the response regulator LuxO. In the unphosphorylated form, LuxO is unable to transcribe the Qrr1-4 sRNAs (grey), and, despite the presence of the RNA chaperone Hfq, the quorum-sensing master regulator HapR is produced. HapR positively regulates transcription of pilA and chiA-1 while repressing transcription of dns. By up-regulating expression of the transcription factor QstR, HapR also indirectly exerts positive effect on transcription of comEA and comEC. An unknown cofactor was also implicated in the transcriptional regulation by QstR. The lines connecting components of the signaling cascade represent positive or negative regulation, but not direct interaction. Grey lines and factors indicate inactive pathways and factors not present at high cell density. IM = inner membrane; OM = outer membrane.

HapR plays a crucial role in modulating chitin-induced natural competence in V. cholerae (Fig. 4). Deletion of hapR, which abolishes many phenotypes controlled by quorum sensing, also eliminates DNA uptake. Natural transformation can be restored by introducing hapR in trans, suggesting that HapR is required for this process (Meibom et al., 2005). Accordingly, both transformation frequency and comEA expression are affected by AI levels, with CAI-1 eliciting a stronger response than AI-2 (Antonova and Hammer, 2011; Suckow et al., 2011). In addition, within a mixed-species biofilm, V. cholerae cells can become competent in response to AIs that are produced from other Vibrio spp. located within the biofilm, suggesting that quorum sensing may facilitate DNA exchange among members of the genus (Antonova and Hammer REF). Such interspecies HGT has yet to be demonstrated under laboratory conditions, and detecting low-frequency events will probably be difficult. Interestingly, a homologue of ComP, which dictates DNA sequence specificity in N. meningitidis (Cehovin et al., 2013), is absent from the genomes of Vibrio spp. In addition, Vibrio spp. do not use a typical generalized DUS to recognize species-specific DNA during natural transformation, which is contrary to the case in H. influenzae, which also lacks a ComP homologue but still relies on DUS for sequence specificity (Mell et al., 2012; Suckow et al., 2011). Quorum sensing, which does not regulate competence in Neisseria spp., may provide Vibrionaceae members with a ComP/DUS-independent, yet species-specific mechanism to prevent the general uptake and genomic incorporation of exogenous DNA from unrelated bacterial species (Suckow et al., 2011).

Progress has been made in elucidating the mechanism by which HapR controls competence. During HCD, HapR repression of dns (Fig. 4), which encodes an extracellular nuclease (Fig. 1), is believed to allow for sufficient single-stranded DNA in the periplasm for transport into the cytoplasm (Meibom et al., 2005; Blokesch and Schoolnik, 2008). Transcript abundance of dns is higher in a ΔhapR mutant than in a ΔluxO mutant that constitutively expresses hapR (Blokesch and Schoolnik, 2008; Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2012), and a Δdns mutant is ‘hyper-transformable’, with transformation frequencies two orders of magnitude higher than a wild-type strain (Blokesch and Schoolnik, 2008). Therefore, it was suggested that the non-transformability of a ΔhapR mutant is partly due to the failure to repress dns, causing constant degradation of extracellular DNA. Consistent with this model, the transformation frequency of a ΔhapR mutant can be restored to wild-type levels by deleting dns (Blokesch and Schoolnik, 2008). Finally, HapR appears to directly bind to the dns promoter to prevent transcription (Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2013), despite the lack of a conventional HapR binding site (Tsou et al., 2009). These studies suggest that quorum signaling permits Dns-mediated degradation of extracellular DNA at low cell density but represses Dns at high cell density, thereby preserving DNA for natural transformation.

HapR also positively regulates expression of comEA and comEC (Fig. 4), which encode components of the competence machinery important for DNA uptake (Fig. 1, Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2013). However, regulation of these genes by HapR appears indirect, as HapR does not directly bind to the promoters of comEA or comEC (Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2013). Instead, a LuxR-type transcription regulator named QstR, whose expression requires HapR (Fig. 4), was recently reported to be involved in the intermediate step (Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2013).

Additional evidence indicates that HapR also activates pilA and chiA-1, which encode a component of the pseudo-pilus and a chitinase, respectively (Fig. 4, Meibom et al., 2005; Antonova et al., 2012). A ΔhapR mutant shows significantly decreased expression of pilA and chiA-1 when compared to the wild-type strain C6706 (Antonova et al., 2012). These results are similar to HapR control of comEC and comEA, further highlighting the important role that HapR plays in regulating competence in strain C6706. Surprisingly, similar studies of A1552, another pathogenic isolate of V. cholerae, show HapR-independent expression of these genes (Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2013). Studies of additional V. cholerae clinical and environmental isolates are required to determine the general role of HapR and quorum sensing in natural transformation. Since HapR also regulates many target genes via synthesis of the intracellular second messenger cyclic-di-GMP (Galperin, 2004; Waters et al., 2008), the contribution of HapR to natural competence likely includes direct and indirect control of competence genes.

Availability of carbon sources

Extracellular DNA taken up by bacteria may also be used as a food source during times of nutrient starvation (Redfield, 1993; Finkel and Kolter, 2001; Palchevskiy and Finkel, 2009). When resources are abundant, bacteria, like Escherichia coli, utilize preferred carbon sources such as glucose while repressing genes involved in catabolism of less favored substrates. However, when preferred carbon sources are unavailable, genes are expressed to internalize and metabolize alternative carbon sources. Carbon catabolite repression (CCR) controls carbon source utilization in this manner. CCR in Gram-negative bacteria is mediated by the secondary messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and the transcriptional activator cAMP receptor protein (CRP). When glucose is absent, intracellular concentrations of cAMP increase (Fig. 5, Bruckner and Titgemeyer, 2002; Deutscher, 2008). cAMP allosterically binds to CRP, and the resulting CRP-cAMP complex binds to and activates promoters by recruiting RNA polymerase (Tagami and Aiba, 1998; Busby and Ebright, 1999). In addition to controlling expression of genes involved in catabolism of sugar substrates, CCR also regulates genes important for virulence in many pathogens such as S. pneumoniae, Salmonella enterica, Staphylococcus aureus and V. cholerae (Skorupski and Taylor, 1997; Iyer et al., 2005; Seidl et al., 2006; Teplitski et al., 2006).

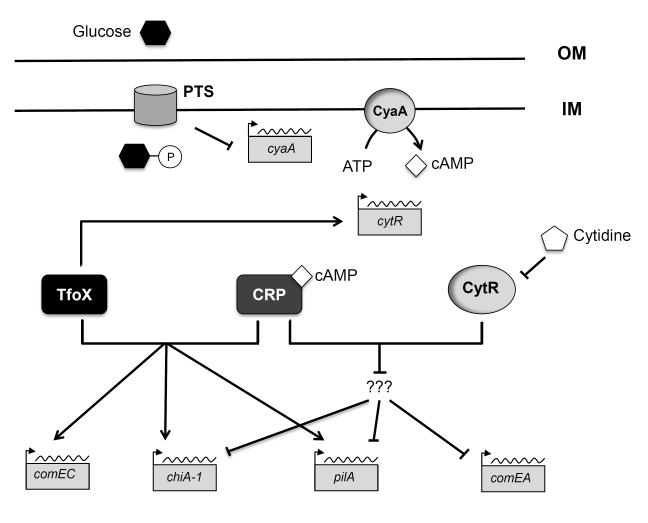

Fig. 5. Impact of external carbon-source and nucleosides on natural transformation pathways in V. cholerae.

In the absence of a preferred carbon source, CyaA increases the intracellular concentration of cAMP. The cAMP-CRP complex interacts with TfoX to activate transcription of multiple genes involved in natural transformation (pilA, comEC and dprA) and in chitin metabolism (chiA-1). When pyrimidine levels are low, the nucleoside scavenging cytidine repressor CytR interacts with CRP to anti-activate putative repressors of comEA, pilA and chiA-1, resulting in upregulation of these genes. The model is over-simplified, and it remains unknown whether comEA, pilA and chiA-1 share a common repressor that is regulated by CytR-CRP. The lines connecting components of the signaling cascade represent positive or negative regulation, but not direct interaction. IM = inner membrane; OM = outer membrane.

A role of CCR in inducing natural competence in V. cholerae was demonstrated by the inhibition of natural transformation by glucose (Fig. 5, Meibom et al., 2005). A separate study showed that a Δcrp mutant, as well as a Δcya mutant that was incapable of synthesizing cAMP, were recalcitrant to transformation either on chitinaceous surfaces or in liquid culture (Blokesch, 2012), which was consistent with previous reports in H. influenzae (Chandler, 1992; Dorocicz et al., 1993). The Δcya and Δcrp mutations also significantly decreased expression of competence genes pilA, pilM, and comEA, albeit not completely abolishing the expression of these genes like in H. influenzae and E. coli (Blokesch, 2012; Cameron and Redfield, 2008). On the other hand, natural transformation increased in a mutant unable to degrade intercellular cAMP, which provides strong evidence that CCR is involved in controlling numerous competence genes (Blokesch 2012; Lo Scrudato and Blokesch 2012). Interestingly, CRP mutants have also been shown to repress hapR expression by reducing CAI-1 synthesis (Liang et al., 2008), thus indirectly modulating natural competence via quorum sensing as well.

Extracellular nucleosides

The intricate response to nutrient starvation mediated by CRP typically involves other regulatory factors that enable bacteria to utilize not only various sugars but also nucleic acids. In E. coli, many genes responsible for scavenging and metabolizing extracellular pyrimidine nucleosides are negatively regulated by the cytidine repressor CytR (Fig. 5, Valentin-Hansen et al., 1996). When free nucleosides are scarce, CytR binds with CRP and acts as an “anti-activator” of the promoters of specific CRP-activated genes involved in nucleoside transport and breakdown. However, in the presence of pyrimidines, cytidine enters the cell and binds allosterically to CytR. Conformational changes in CytR when in complex with cytidine hamper association with CRP and, as a result, eliminate CytR-dependent anti-activation of CRP-regulated genes. CRP can then activate expression of these promoters by recruiting RNA polymerase (Barbier et al., 1997). Thus, genes required for nucleoside uptake and metabolism are only expressed in the presence of the nucleosides themselves.

Availability of nucleotides such as purine was also shown to play an important role in regulating natural competence in H. influenzae (MacFadyen et al., 2001; Sinha et al., 2013). However, the H. influenzae genome lacks a CytR homologue, and a functionally similar protein, PurR, was found not to be responsible for purine-mediated repression of competence (Sinha et al., 2013). Interestingly, cytR was originally identified as a V. cholerae gene regulated by TfoX (Fig. 5, Meibom et al., 2005). However, its specific role in natural competence was revealed only recently, when a ΔcytR mutant was shown to be non-transformable and displayed decreased expression of comEA, chiA-1, and pilA (Fig. 5, Antonova et al., 2012). The presence of nucleosides, namely cytidine, also inhibited both transformation and comEA expression directly, suggesting a regulatory mechanism similar to that proposed in H. influenzae (Antonova et al., 2012). Mutants containing CytR variants unable to bind to CRP were impaired for transformation, suggesting that the CytR-CRP protein-protein interactions important for nucleoside scavenging in E. coli are also vital to activating natural competence genes in V. cholerae (Antonova et al., 2012). Although the exact role of nucleotide scavenging in natural competence has yet to be determined, these results provide evidence that natural competence in the Vibrionaceae may be used not only for HGT but also for nutrient acquisition.

TfoX: an integral regulator of natural transformation

The tfoX gene was originally identified among other V. cholerae genes that display elevated expression levels in response to chitin (Meibom et al., 2004). TfoX is required for chitin-dependent natural transformation in V. cholerae (Meibom et al., 2005). When constitutively expressed, TfoX can induce genetic competence in the absence of chitin (Meibom et al., 2005). A homologue of TfoX named Sxy plays a central role in controlling genetic competence in H. influenzae (Williams et al., 1994; Zulty and Barcak, 1995; Redfield et al., 2005), Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Bhattacharjee et al., 2007), Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (Bosse et al., 2009) and Actinobacillus suis (Sinha et al., 2013). E. coli also possesses a homologue of Sxy, but expression of E. coli Sxy is insufficient to induce natural transformation in this organism, despite activating expression of homologues of competence genes that are used by other bacterial species (Cameron and Redfield, 2006; Sinha et al., 2009; Sinha and Redfield, 2012).

Chitin, either in the form of crab shells or oligosaccharides, enhances the production of TfoX, at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels (Fig. 3) (Yamamoto et al., 2010). Genetic studies in V. cholerae have shown that chitin is sensed by the hybrid sensor kinase ChiS, which in turn promotes production of a small regulatory RNA named TfoR (Fig. 3, Li and Roseman, 2004; Meibom et al., 2004; Yamamoto et al., 2010; Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2012). The signaling pathway initiated by ChiS that leads to tfoR expression remains unclear. TfoR is predicted to base pair with the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of the tfoX transcript, thus preventing formation of an inhibitory secondary structure that sequesters the predicted Shine-Dalgarno sequence for tfoX (Fig. 3, Yamamoto et al., 2011). Translational activation of tfoX by TfoR also requires the RNA chaperone Hfq (Fig. 3), which is often a crucial player in trans-encoded small RNA-mediated regulation (Vogel and Luisi, 2011; Yamamoto et al., 2011). A transcriptional repressor element was also identified within the tfoX promoter in V. cholerae (Yamamoto et al., 2010). However, in contrast to the strong translational regulation described above, the transcriptional derepression of tfoX by chitin and (GlcNAc)n is moderate, and the transcription factor involved in this process remains unknown (Yamamoto et al., 2010). In H. influenzae, which does not possess a TfoR homolog, transcription of sxy is strongly induced by the CRP-cAMP complex (Zulty and Barcak, 1995). Whether CRP-cAMP affects tfoX transcription in V. cholerae remains unknown at this time. Future studies of tfoX regulation will greatly help our understanding of how the Vibrionaceae process the external chitin signal to become genetically competent.

TfoX activates the expression of many genes involved in chitin degradation and chitin-induced competence in V. cholerae (Meibom et al., 2005). Members of the chitin-dependent TfoX regulon include the pilQ, pilA, comEA, and comEC genes (Fig. 3), whose gene products play essential roles in the uptake and transport of exogenous DNA (Fig. 1, Fullner and Mekalanos, 1999; Meibom et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2005; Hamilton and Dillard, 2006; Claverys et al., 2009; Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2012). In addition, expression of a gene encoding a homolog of DprA, which plays a crucial role in the integration of exogenous DNA, was reported to be elevated in response to induction of tfoX expression (Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2012). In H. influenzae, Sxy is proposed to direct the CRP-cAMP complex to a noncanonical CRP (CRP-S) site (TGCGA-N6-TCGCA) within the promoter regions of competence genes (Cameron and Redfield, 2006; Cameron and Redfield, 2008). These studies suggested that Sxy may serve as an accessory factor to CRP, rather than a primary transcription factor, in promoting expression of competence genes (Redfield et al., 2005; Cameron and Redfield, 2006; Sinha et al., 2012). This model is consistent with the lack of an obvious DNA-binding domain in Sxy. The demonstration that cAMP, presumably in complex formation with CRP, is required for chitin-dependent induction of comEA and pilA in V. cholerae further highlights that TfoX may also serve as an accessory factor (Fig. 4, Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2012). Consistent with this hypothesis, potential CRP-S sites are located within the promoter regions of comEA and pilA (Antonova et al., 2012). A common motif 5′-ACTCG(A/C)AA was identified in most of the 19 TfoX-induced promoter elements by means of a phylogenetic footprint analysis (Cameron and Redfield, 2006). At this time, whether TfoX binds DNA in complex with CRP has not yet been directly examined by experimental approaches.

Recently, TfoX was shown to positively regulate the expression of two transcription factors: CytR and QstR (Fig. 3, Meibom et al., 2005; Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2013). As described in the previous section, CytR is the nucleoside scavenging cytidine repressor that represses expression of comEA, pilA, and chiA-1 in V. cholerae (Fig. 5, Antonova et al., 2012). TfoX also activates transcription of qstR (Fig. 3), which encodes a transcription factor essential for comEA and comEC expression (Fig. 4, Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2013). Activation of QstR also requires the major regulator of quorum sensing, HapR (Fig. 4, Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2013), which accounts for the subset of TfoX-regulated genes that are also controlled by quorum sensing (Lo Scrudato and Blokesch, 2012). Together, these studies underscore the complex roles of TfoX in coordinating expression of the genes required for competence in V. cholerae.

Natural transformation in other Vibrio species

Recently, homologues of TfoX were identified in all sequenced Vibrionaceae members (Pollack-Berti et al., 2010). This observation, combined with the highly conserved ability of Vibrionaceae members to utilize chitin as a nutrient (Hunt et al., 2008), strongly support the notion that chitin-induced natural transformation is a shared trait among the Vibrionaceae. While the presence of chitin and chitin-derived oligosaccharides does induce natural competence in various Vibrio spp., differences between these organisms have been detected and are highlighted here.

Vibrio fischeri

V. fischeri is a bioluminescent bacterium commonly found in free-living form within marine environments, as well as in symbiotic relationships with marine animals, such as the Hawaiian bobtail squid Euprymna scolopes (Visick and Ruby, 2006; Miyashiro and Ruby, 2012). When grown in the presence of chitohexaose (GlcNAc)6, V. fischeri can incorporate exogenous DNA into its chromosome via natural transformation (Pollack-Berti et al., 2010). V. fischeri also possesses tfoX, which is a homolog of the V. cholerae tfoX gene and similarly required for the (GlcNAc)6 -dependent natural transformation in V. fischeri. When multiple copies of tfoX are present (i.e., on a plasmid), tfoX is capable of inducing genetic competence in V. fischeri independently of (GlcNAc)6 (Pollack-Berti et al., 2010). A paralog of tfoX named tfoY was also identified in the V. fischeri genome and shown to play a role in (GlcNAc)6-dependent natural transformation. Intriguingly, tfoX in trans restores (GlcNAc)6-induced genetic competence in a ΔtfoY mutant, while tfoY in multi-copy fails to compensate for the loss of tfoX or result in (GlcNAc)6-dependent transformation, suggesting functional differences between the two homologs (Pollack-Berti et al., 2010). In the simplest model to explain these observations, TfoY serves to positively regulate TfoX in a pathway of chitin-induced natural competence. Since TfoY orthologs were also identified in other Vibrio spp., including V. cholerae (Pollack-Berti et al., 2010), studying the regulation of tfoY expression in response to chitin as well as its functions in chitin-induced natural competence will add valuable insights to our understanding of the gene transfer processes.

Remarkably, polymeric chitin in the form of crab-shell tiles, which can induce natural competence in V. cholerae (Meibom et al., 2005; Antonova and Hammer, 2011; Antonova et al., 2012), fails to do so in V. fischeri (Pollack-Berti et al., 2010). Even in the presence of (GlcNAc)6, V. fischeri exhibits significantly lower levels of natural transformation than V. cholerae (Pollack-Berti et al., 2010). The underlying causes of these discrepancies are unknown. Perhaps in V. fischeri, the chitin-dependent competence cascade (e.g. production or activities of TfoX) is under more stringent regulatory control. Alternatively, V. fischeri may have higher extracellular DNase activity than V. cholerae. These scenarios may not be mutually exclusive and additional investigation is required.

Recently, in V. fischeri, the N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc) transcriptional repressor NagC was shown to negatively regulate the expression of numerous chitin- and GlcNAc-utilization genes, including VF_2139, which is predicted to encode the chitin oligosaccharide-binding protein (CBP) (Miyashiro et al., 2011). CBP was proposed to play an essential part in the ChiS-mediated chitin-sensing pathways in V. cholerae, which eventually leads to chitin-dependent natural transformation (Li and Roseman, 2004; Meibom et al., 2005). It is therefore conceivable that NagC may also be involved in regulating genetic competence in V. fischeri. On the other hand, NagC-mediated gene regulation responds to extracellular GlcNAc (and its phosphorylated form N-acetyl-D-glucosamine-6-phosphate) (Miyashrio et al., 2011), which does not induce natural competence in V. fischeri or V. cholerae (Pollack-Berti et al., 2010; Yamamoto et al., 2010). Taken together, these observations suggest that any potential role of NagC in chitin-responsive natural transformation in V. fischeri is likely to be complex. Intriguingly, chitin oligosaccharides produced by E. scolopes also serve as chemotactic signals for V. fischeri to facilitate host colonization (Mandel et al., 2012). Whether the level of chitin oligosaccharides encountered by V. fischeri cells during colonization is sufficient to induce the natural competence pathway has yet to be determined.

Vibrio vulnificus

V. vulnificus is another member of the Vibrionaceae family present in marine environments, such as estuaries, and is an opportunistic human pathogen that causes primary septicemia and wound infection (Jones and Oliver, 2009). Like V. cholerae, V. vulnificus becomes naturally competent while growing on chitin and can both take up and incorporate exogenous DNA (Gulig et al., 2009). Chitin disaccharides (GlcNAc)2, but not GlcNAc, can also induce natural competence in V. vulnificus (Neiman et al., 2011). The frequency of chitin-induced transformation varies among different strains. Interestingly, transformation frequency can be significantly improved by exposing biofilms comprised of different isolates to strain-specific lytic phage, which presumably leads to increased amount of extracellular DNA from cell lysis (Neiman et al., 2011). In this study, V. vulnificus, when exposed to chitin, was able to take up and incorporate within its chromosome exogenous genomic DNA containing a complete cps loci that encodes capsular polysaccharide, which is a virulence factor. As a result of this transformation, the tested V. vulnificus strain underwent carbotype (capsule type) conversion. Diversity of carbotypes among V. vulnificus strains is thought to help this organism evade a host’s immune system. Based on these results, it was proposed that chitin-induced transformation could potentially play an important role in the evolution of V. vulnificus (Neiman et al., 2011).

Vibrio parahaemolyticus

V. parahaemolyticus is a halophilic bacterium found in brackish seawater and can cause gastrointestinal illness in humans (Chen et al., 2011). In 1990, a V. parahaemolyticus strain was experimentally demonstrated to pick up exogenous plasmid DNA (Frischer et al., 1990). Furthermore, a more recent study reported that chitin (in the form of crab shells) enables V. parahaemolyticus to pick up and incorporate exogenous linear DNA, which has been adapted as a genetic tool to generate specific mutations (Chen et al., 2010).

Environmental and clinical implications

Although still under intense debate, numerous studies suggest that bacteria, including Vibrionaceae members, have evolved the competence pathway to aid in three major processes: nutrition, DNA repair and horizontal gene transfer (HGT) (Redfield 1993; Solomon and Grossman, 1996; Dubnau, 1999). A particularly popular model is that natural transformation functions as a common mechanism for HGT (Paul et al., 1991; Dubnau, 1999). Natural competence is linked to enhanced genetic diversity, improved fitness, and, in some cases, increased virulence in Vibrio spp. Due to the abundance of the Vibrionaceae in a wide range of aquatic ecosystems, and their close association with various marine and freshwater plants and animals, natural competence in the Vibrionaceae is expected to have significant environmental, ecological and clinical implications. A previous study designed to mimic aquatic reservoirs demonstrated that, through chitin-induced natural transformation, a V. cholerae strain can acquire a gene cluster (Blokesch and Schoolnik, 2007), which effectively converts the recipient into a different serogroup (Bik et al., 1995, Mooi and Bik 1997) that is known for its heightened fitness, virulence and central role in the 1992 cholera epidemic (Albert et al., 1997). V. cholerae strains lacking the cholera toxin (ctxAB) genes required to cause cholera, can also acquire DNA encoding ctxAB via chitin-induced natural competence (Udden et al., 2008). The potential involvement of chitin-induced natural transformation in enhancing virulence was also shown in V. vulnificus (Neiman et al., 2011). In the latter two cases (V. cholerae acquiring cholera toxin genes and V. vulnificus obtaining virulence genes), presence of the species and strain-specific lytic phages greatly enhanced transformation frequencies. In particular, exposure of the Vibrio cultures to DNase exhibited negative effects on the transformation efficiency (Udden et al., 2008; Neiman et al., 2011). These results suggest that phage could release cellular DNA that could contribute to natural transformation. Such bacteriolytic mechanisms are used by other naturally competent bacterial species, such S. pneumoniae and B. subtilis, in the provision of donor DNA (Claverys and Håvarstein, 2007; Wei and Håvarstein, 2012). In contrast, N. gonorrhoeae uses a type IV secretion system encoded in the gonococcal genetic island to secret DNA outside the cells, and mutation in this system reduces the ability of a N. gonorrhoeae strain to act as a donor in transformation. Together, these studies highlight the various strategies employed by bacteria to acquire DNA from exogenous sources.

Importantly, the impact of natural transformation is unlikely to be solely limited to enhancing the overall pathogenicity of Vibrio spp. For instance, chitin-induced natural transformation was shown to facilitate the transfer of gene clusters encoding different metabolic functions (mannose and diglucosamine utilization) (Miller et al., 2007). Since Vibrionaceae members are well known for their contribution in the carbon and nitrogen cycle (Criminger et al., 2007; Anorsti, 2011), mutations in metabolic genes as a result of natural transformation could affect the overall metabolite levels in the aquatic environments.

Outlook

Natural competence in Vibrionaceae and its ecological and clinical impact have been attracting increasing amount of interest in the scientific community in the recent years. There are still many unanswered questions regarding the underlying molecular mechanisms of natural competence, as well as the physiological (both short-term and long-term) ramifications of taking up exogenous DNA. As more environmental and genetic factors controlling the regulation of natural competence have been uncovered, it will certainly improve our understanding of this important biological phenomenon and provide valuable insight in the microbial adaptation to environmental cues.

Acknowledgements

We thank Subhash C. Verma and the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticisms of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH Grant 4R00GM090732 to T.M. and NSF Grant MCB-0919821 to B.K.H.

References

- Aas FE, Wolfgang M, Frye S, Dunham S, Løvold C, Koomey M. Competence for natural transformation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: components of DNA binding and uptake linked to type IV pilus expression. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:749–760. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam M, Sultana M, Nair G, B Siddique, A K, Hasan NA, Sack RB, et al. Viable but nonculturable Vibrio cholerae O1 in biofilms in the aquatic environment and their role in cholera transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17801–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705599104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert MJ, Bhuiyan NA, Talukder KA, Farugue AS, Nahar S, Faruque SM, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic changes in Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2588–2592. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2588-2592.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amako K, Shimodori S, Imoto T, Miake S, Umeda A. Effects of chitin and its soluble derivatives on survival of Vibrio cholerae O1 at low temperature. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:603–605. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.3.603-605.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anorsti C. Microbial extracellular enzymes and the marine carbon cycle. Ann Rev Mar Sci. 2011;3:401–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonova ES, Bernardy EE, Hammer Brian K. Natural competence in Vibrio cholerae is controlled by a nucleoside scavenging response that requires CytR-dependent anti-activation. Mol Microbiol. 2012;86:1215–1231. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonova ES, Hammer BK. Quorum-sensing autoinducer molecules produced by members of a multispecies biofilm promote horizontal gene transfer to Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;322:68–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier CS, Short SA, Senear DF. Allosteric mechanism of induction of CytR-regulated gene expression. CytR repressor-cytidine interaction. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16962–16971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardill JP, Hammer BK. Non-coding sRNAs regulate virulence in the bacterial pathogen Vibrio cholerae. RNA Biol. 2012;9:392–401. doi: 10.4161/rna.19975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardill JP, Zhao X, Hammer BK. The Vibrio cholerae quorum sensing response is mediated by Hfq-dependent sRNA/mRNA base pairing interaction. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:1381–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler BL, Greenberg EP, Stevens AM. Cross-species induction of luminescence in the quorum-sensing bacterium Vibrio harveyi. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4043–4045. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.4043-4045.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler BL, Gibbons P, Roseman S. Chemotaxis to chitin oligosaccharides by Vibrio furnissii, a chitinivorous marine bacterium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;161:1172–1176. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91365-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee MK, Fine DH, Figurski DH. tfoX (sxy)-dependent transformation of Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans. Gene. 2007;399:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bik EM, Bunschoten AE, Gouw RD, Mooi F. Genesis of the novel epidemic Vibrio cholerae O139 strain: evidence for horizontal transfer of genes involved in polysaccharide synthesis. EMBO J. 1995;14:209–216. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb06993.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas GD, Sox T, Blackman E, Sparling P. Factors affecting genetic transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol. 1977;129:983–992. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.2.983-992.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokesch M, Schoolnik GK. The extracellular nuclease Dns and its role in natural transformation of Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7232–7240. doi: 10.1128/JB.00959-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokesch M. Chitin colonization, chitin degradation and chitin-induced natural competence of Vibrio cholerae are subject to catabolite repression. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14:1898–1912. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokesch M, Schoolnik GK. Serogroup conversion of Vibrio cholerae in aquatic reservoirs. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e81. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokesch M, Schoolnik GK. The extracellular nuclease Dns and its role in natural transformation of Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7232–40. doi: 10.1128/JB.00959-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossé JT, Sinha S, Schippers T, Kroll JS, Redfield RJ, Langford PR. Natural competence in strains of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 298:124–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner R, Titgemeyer F. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: choice of the carbon source and autoregulatory limitation of sugar utilization. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;209:141–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby S, Ebright RH. Transcripton activation by catabolite actviator protein (CAP) J Mol Biol. 1999;293:199–213. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AD, Redfield RJ. Non-canonical CRP sites control competence regulons in Escherichia coli and many other gamma-proteobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6001–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron ADS, Redfield RJ, Rosemary J. CRP binding and transcription activation at CRP-S sites. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:313–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cehovin A, Simpson PJ, McDowell MA, Brown DR, Noschese R, Pallett M, et al. Specific DNA recognition mediated by a type IV pilin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:3065–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218832110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MS. The gene encoding cAMP receptor protein is required for competence development in Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1626–1630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen I, Dubnau D. DNA uptake during bacterial transformation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:241–9. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro844. (2004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen I, Christie PJ, Dubnau D. The ins and outs of DNA transfer in bacteria. Science. 2005;310:1456–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1114021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Dai J, Morris JG, Johnson JA. Genetic analysis of the capsule polysaccharide (K antigen) and exopolysaccharide genes in pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:274. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Stine OC, Badger JH, Gil AI, Nair GB, Nishibuchi M, Fouts DE. Comparative genomic analysis of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: serotype conversion and virulence. BMC Genomics. 2011;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claverys JP, Håvarstein LS. Cannibalism and fratricide: mechanisms and raisons d’être. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:219–29. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claverys JP, Martin B, Polard P. The genetic transformation machinery: composition, localization, and mechanism. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33:643–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criminger JD, Hazen TH, Sobecky PA, Lovell CR. Nitrogen fixation by Vibrio parahaemolyticus and its implications for a new ecological niche. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5959–5961. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00981-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher J. The mechanisms of carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorocicz IR, Williams PM, Redfield RJ. The Haemophilus influenzae adenylate cyclase gene: cloning, sequence, and essential role in competence. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7142–7149. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7142-7149.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubnau D. DNA uptake in bacteria. Gene. 1999;53:217–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel SE, Kolter R. DNA as a nutrient: Novel role for bacterial competence gene homologs. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6288–6293. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6288-6293.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischer ME, Thurmond JM, Paul JH. Natural plasmid transformation in a high-frequency-of-transformation marine Vibrio strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3439–3444. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3439-3444.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullner KJ, Mekalanos JJ. Genetic characterization of a new type IV-A pilus gene cluster found in both classical and El Tor biotypes of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1393–1404. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1393-1404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY. Bacterial signal transduction network in a genomic perspective. Environ Microbiol. 2004;6:552–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulig PA, Tucker MS, Thiaville PC, Joseph JL, Brown RN. USER friendly cloning coupled with chitin-based natural transformation enables rapid mutagenesis of Vibrio vulnificus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:4936–49. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02564-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton HL, Dillard JP. Natural transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: from DNA donation to homologous recombination. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:376–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer BK, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:101–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt DE, Gevers D, Vahora NM, Polz MF. Conservation of the chitin utilization pathway in the Vibrionaceae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:44–51. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01412-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huq A, Small EB, West P, Huq M, Rahman R, Colwell RR. Ecological relationships between Vibrio cholerae and planktonic crustacean copepods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45:275–83. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.1.275-283.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer R, Baliga NS, Camilli A. Catabolite control protein A (CcpA) contributes to virulence and regulation of sugar metabolism in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:8340–8349. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.24.8340-8349.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MK, Oliver JD. Vibrio vulnificus: Disease and Pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1723–1733. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01046-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyhani NO, Roseman S. Physiological aspects of chitin catabolism in marine bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1473:108–122. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirn TJ, Jude BA, Taylor RK. A colonization factor links Vibrio cholerae environmental survival and human infection. Nature. 2005;438:863–866. doi: 10.1038/nature04249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lång E, Haugen K, Fleckenstein B, Homberset H, Frye SA, Ambur OH, Tønjum T. Identification of neisserial DNA binding components. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2009;155:852–62. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.022640-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz DH, Mok KC, Lilley BN, Kulkarni Rahul V, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL. The small RNA chaperone Hfq and multiple small RNAs control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell. 2004;118:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Roseman S. The chitinolytic cascade in Vibrios is regulated by chitin oligosaccharides and a two-component chitin catabolic sensor/kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:627–631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307645100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang W, Sultan SZ, Silva AJ, Benitez JA. Cyclic AMP post723 transcriptionally regulates the biosynthesis of a major bacterial autoinducer to modulate the cell density required to activate quorum sensing. FEMS Lett. 2008;582:3744–3750. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Scrudato M, Blokesch M. The regulatory network of natural competence and transformation of Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Scrudato M, Blokesch M. A transcriptional regulator linking quorum sensing and chitin induction to render Vibrio cholerae naturally transformable. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013:1–15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFadyen LP, Chen D, Vo HC, Liao D, Sinotte R, Redfield RJ. Competence development by Haemophilus influenzae is regulated by the availability of nucleic acid precursors. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:700–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel MJ, Schaefer AL, Brennan CA, Heath-Heckman EAC, Deloney-Marino CR, McFall-Ngai MJ, Ruby EG. Squid-derived chitin oligosaccharides are a chemotactic signal during colonization by Vibrio fischeri. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:4620–6. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00377-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin MA, Thompson CC, Freitas FS, Fonseca EL, Aboderin AO, Zailani SB, et al. Cholera Outbreaks in Nigeria Are Associated with Multidrug Resistant Atypical El Tor and Non-O1/Non-O139 Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meibom KL, Blokesch M, Dolganov NA, Wu CY, Schoolnik GK. Chitin induces natural competence in Vibrio cholerae. Science. 2005;310:1824–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1120096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meibom KL, Li XB, Nielsen AT, Wu CY, Roseman S, Schoolnik GK. The Vibrio cholerae chitin utilization program. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2524–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308707101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mell JC, Hall IM, Redfield RJ. Defining the DNA uptake speceficity of naturally competent Haemophilus influenzae cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:8536–49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MC, Keymer DP, Avelar A, Boehm AB, Schoolnik GK. Detection and transformation of genome segments that differ within a coastal population of Vibrio cholerae strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:3695–3704. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02735-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashiro T, Ruby EG. Shedding light on bioluminescence regulation in Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol. 2012;84:795–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashrio T, Klein W, Oehlert D, Cao X, Schwartzman J, Ruby EG. The N-acetyl-D-glucosamine repressor NagC of Vibrio fischeri facilitates colonization of Euprymna scolopes. Mol Microbiol. 2011;82:894–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooi FR, Bik EM. The evolution of epidemic Vibrio cholerae strains. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:161–165. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(96)10086-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiman J, Guo Y, Rowe-Magnus DA. Chitin-Induced Carbotype Conversion in Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Immun. 2011;79:3195–3203. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00158-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng WL, Bassler BL. Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:197–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palchevskiy V, Finkel SE. A role for single-stranded exonucleases in the use of DNA as a nutrient. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3712–6. doi: 10.1128/JB.01678-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JH, Frischer ME, Thurmond JM. Gene Transfer in Marine Water Column and Sediment Microcosms by Natural Plasmid Transformation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1509–1515. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.5.1509-1515.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piarroux R, Faucher B. Cholera epidemics in 2010: respective roles of environment, strain changes, and human-driven dissemination. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:231–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack-Berti A, Wollenberg MS, Ruby EG. Natural transformation of Vibrio fischeri requires tfoX and tfoY. Environmental microbiology. 2010;12:2302–2311. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruzzo C, Vezzulli L, Colwell RR. Global impact of Vibrio cholerae interactions with chitin. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:1400–1410. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfield RJ. Genes for breakfast: the have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too of bacterial transformation. J Hered. 1993;84:400–4. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfield RJ, Cameron AD, Qian Q, Hinds J, Ali TR, Kroll JS, Langford PR. A novel CRP-dependent regulon controls expression of competence genes in Haemophilus influenzae. J Mol Biol. 2005;347:735–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reguera G, Kolter R. Virulence and the environment: a novel role for Vibrio cholerae toxin-coregulated pili in biofilm formation on chitin. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3551–3555. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.10.3551-3555.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack DA, Sack RB, Nair GB, Siddique AK. Cholera. Lancet. 2004;363:223–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidl K, Stucki M, Ruegg M, Goerke C, Wolz C, Harris L, et al. Staphylococcus aureus CcpA affects virulence determinant production and antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1183–1194. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1183-1194.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senderovich Y, Izhaki I, Halpern M. Fish as reservoirs and vectors of Vibrio cholerae. PloS One. 2010;5:e8607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seper A, Fengler VH, Roier S, Wolinski H, Kohlwein SD, Bishop AL, et al. Extracellular nucleases and extracellular DNA play important roles in Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 2011;82:1015–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Cameron AD, Redfield RJ. Sxy induces CRP-S regulon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5180–5195. doi: 10.1128/JB.00476-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Mell JC, Redfield RJ. Seventeen Sxy-dependent cyclic AMP receptor protein site-regulated genes are needed for natural transformation in Haemophilus influenzae. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:5245–5254. doi: 10.1128/JB.00671-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Mell JC, Redfield RJ. The availability of purine nucleotides regulates natural competence by controlling translation of the competence activator Sxy. Mol Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/mmi.12245. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Redfield RJ. Natural DNA uptake by Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skorupski K, Taylor RK. Cyclic AMP and its receptor protein negatively regulate the coordinate expression of cholera toxin and toxin-coregulated pilus in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:265–270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HO. New insights into how bacteria take up DNA during transformation. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29:1085–1088. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1980.29.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon JM, Grossman AD. Who’s competent and when: regulation of natural genetic competence in bacteria. Trends in genetics : TIG. 1996;12:150–5. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suckow G, Seitz P, Blokesch M. Quorum sensing contributes to natural transformation of Vibrio cholerae in a species-specific manner. Journal of bacteriology. 2011;193:4914–24. doi: 10.1128/JB.05396-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagami H, Aiba H. A common role of CRP in transcription activation: CRP acts transiently to stimulate events leading to open complex formation at a diverse set of promoters. EMBO J. 1998;17:1759–1767. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplitski M, Goodier RI, Ahmer BM. Catabolite repression of the SirA regulatory cascade in Salmonella enterica. Int J Med Microbiol. 2006;296:449–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou AM, Cai T, Liu Z, Zhu J, Kulkarni RV. Regulatory targets of quorum sensing in Vibrio cholerae: evidence for two distinct HapR-binding motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:2747–56. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udden SM, Zahid MS, Biswas K, Ahmad QS, Cravioto A, Nair GB, et al. Acquisition of classical CTX prophage from Vibrio cholerae O141 by El Tor strains aided by lytic phages and chitin-induced competence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11951–11956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805560105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin-Hansen P, Søgaard-Andersen L, Pedersen H. A flexible partnership: the CytR anti-activator and the cAMP-CRP activator protein, comrades in transcription control. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:461–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5341056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visick KL, Ruby EG. Vibrio fischeri and its host: it takes two to tango. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J, Luisi BF. Hfq and its constellation of RNA. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:578–589. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters CM, Lu W, Rabinowitz JD, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae through modulation of cyclic di-GMP levels and repression of vpsT. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2527–2536. doi: 10.1128/JB.01756-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watnick PI, Fullner KJ, Kolter R. A Role for the Mannose-Sensitive Hemagglutinin in Biofilm Formation by Vibrio cholerae El Tor. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3606–3609. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3606-3609.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Håvarstein HS. Fractricide is essential for efficient gene transfer between Pneumococci in biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:5897–5905. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01343-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams PM, Bannister LA, Redfield RJ. The Haemophilus influenzae sxy-1 mutation is in a newly identified gene essential for competence. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6789–6794. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6789-6794.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang M, Lauer P, Park HS, Brossay L, Hebert J, Koomy M. PilT mutations lead to simultaneous defects in competence for natural transformation and twitching motility in piliated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 2002;29:321–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Izumiya H, Mitobe J, Morita M, Arakawa E, Ohnishi M, Watanabe H. Identification of a chitin-induced small RNA that regulates translation of the tfoX gene, encoding a positive regulator of natural competence in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:1953–65. doi: 10.1128/JB.01340-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Morita M, Izumiya H, Watanabe H. Chitin disaccharide (GlcNAc)2 induces natural competence in Vibrio cholerae through transcriptional and translational activation of a positive regulatory gene tfoXVC. Gene. 2010;457:42–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Mekalanos JJ. Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev Cell. 2003;5:647–656. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Miller MB, Vance RE, Dziejman M, Bassler BL, Mekalanos JJ. Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3129–3134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052694299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulty JJ, Barcak GJ. Identification of a DNA transformation gene required for com101A+ expression and supertransformer phenotype in Haemophilus influenzae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3616–3620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]