Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of menopausal symptoms and menopausal symptom severity on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), work impairment, healthcare utilization, and costs.

Methods

Data from the 2005 United States National Health and Wellness Survey were used, with only women 40–64 years without a history of cancer included in the analyses (N=8,811). Women who reported experiencing menopausal symptoms (n=4,116) were compared with women not experiencing menopausal symptoms (n=4,695) on HRQoL, work impairment, and healthcare utilization using regression modeling (and controlling for demographics and health characteristic differences). Additionally, individual menopausal symptoms were used as predictors of outcomes in a separate set of regression models.

Results

The mean age of women in the analysis was 49.8 years (standard deviation,±5.9). Women experiencing menopausal symptoms reported significantly lower levels of HRQoL and significantly higher work impairment, and healthcare utilization than women without menopausal symptoms. Depression, anxiety, and joint stiffness were symptoms with the strongest associations with health outcomes.

Conclusions

Menopausal symptoms can be a significant humanistic and economic burden on women in middle age.

Introduction

Menopause is defined as the cessation of menstrual periods for at least 12 consecutive months and not due to physiologic (e.g., lactation) or pathologic causes.1 It is estimated that there are 57 million women in the United States that are at least 45 years of age; approximately 6,000 of these women reach menopause every day.2 The cessation of menstrual periods is often associated with a variety of unpleasant symptoms, including anxiety, depression, decreased libido, vaginal dryness, insomnia, difficulty concentrating, and vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes and night sweats).3 These symptoms may last years after the menopause transition.1 A study by Berecki-Gisolf (2009) demonstrated that many symptoms persisted 7 years after the cessation of their menstrual periods.4

Though not all women who report menopausal symptoms are bothered by them,5 several large studies have demonstrated an association between menopausal symptoms and lower quality of life.6–13 A higher total score on the menopause symptoms checklist (which summarizes psychological, vaso-somatic, and general symptomatic burden)7, higher self-reported frequency of vasomotor symptoms,12 and a greater number of menopausal symptoms7 have all been found to be significantly associated with lower quality of life. The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) measured health-related quality of life of approximately 3,000 women and found that several of the symptoms associated with menopause (e.g., hot flashes, night sweats, vaginal dryness, leaking urine) were also associated with lower quality of life.8–9

Although the humanistic burden of menopausal symptoms has been documented across a variety of instruments, there is a paucity of information regarding the direct and indirect economic costs. However, the limited existing literature suggests that menopausal symptoms incur costs through both increased healthcare utilization and lost productivity. The Do Stage Transitions Result in Detectable Effects? (STRIDE) study found that hot flashes were associated with an additional $1,649 of medical services per woman per year, not including prescriptions or complementary and alternative medicine services.14 In the Menopause Epidemiology Study, a number of women with mild or moderate hot flashes—and the majority of those with severe hot flashes—reported that their symptoms interfered with their productivity at work.12 However, few studies have quantified the extent of the impact of menopausal symptoms on productivity loss,15 and none, to our knowledge, have done so for the general population.

In general, menopausal symptoms are burdensome to many women who suffer from them. Although the impact of these symptoms on health-related quality of life has been reported across a variety of populations incorporating different instruments, the burden these symptoms pose to society through increased healthcare utilization and lost productivity and wages has not been well established. The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of menopausal symptoms on health-related quality of life and productivity and quantify the economic burden.

Methods

Data collection

Data were obtained from the 2005 National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS), an annual, cross-sectional study of adults aged 18 years or older (Kantar Health). This self-administered, internet-based questionnaire was given to a sample identified through a web-based consumer panel whose members were recruited through opt-in emails, co-registration with panel partners, e-newsletter campaigns, and online banner placements. All panelists explicitly agreed to become panel members, registered through unique email addresses, and completed in-depth demographic registration profiles. A stratified random sampling procedure was implemented, using strata based on gender, age, and race/ethnicity in order for the sample to be representative of the demographic composition of the general U.S. adult population. Comparisons between the NHWS and other established sources have been made elsewhere.16 The study was approved by Essex Institutional Review Board (Lebanon, NJ).

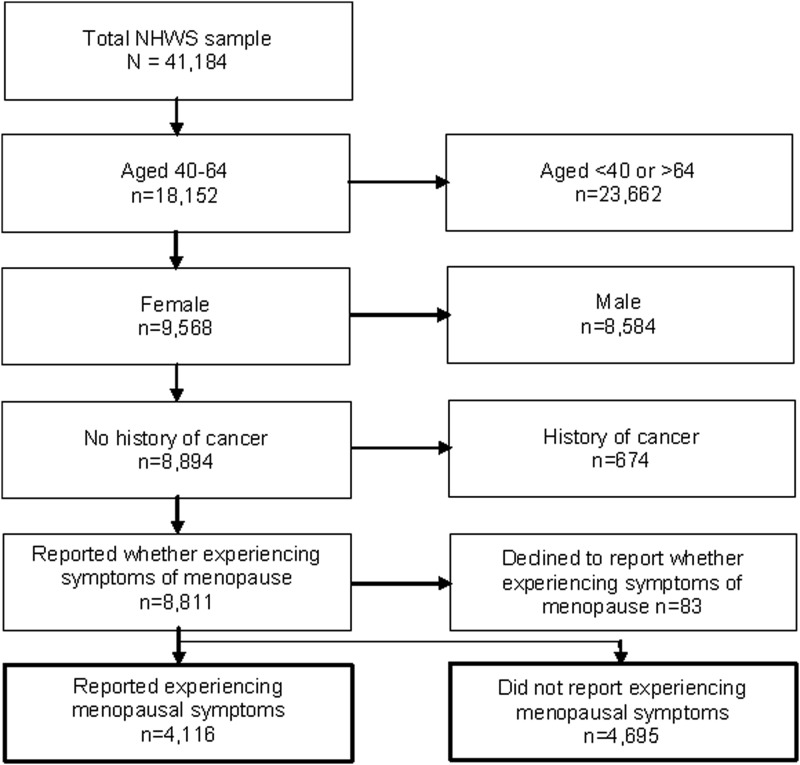

Although the NHWS is conducted annually, the 2005 survey was used in the present study, as it was the most recent survey that assessed menopausal symptoms. Of 229,000 persons contacted to complete the 2005 NHWS, 65,588 responded to the initial invitation to view more information about the study. Of those who viewed more information, 41,184 (62.8%) gave their informed consent to participate, met the inclusion criteria (aged 18 or over), and completed the survey instrument. From the overall NHWS sample, only those who were between the ages of 40 and 64 years (inclusive), female, without a history of cancer, and who had provided data on their menopausal symptoms experience were included (N=8,811; see Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Inclusion and exclusion flowchart.

Measures

Self-reported menopausal symptoms

Women between 40 and 64 years of age were asked about the presence (yes versus no) of the following menopausal symptoms: anxiety, decreased interest in sex, depression, forgetfulness, heart racing or pounding, hot flashes, insomnia/difficulty sleeping, joint stiffness, mood changes, night sweats, urine leakage, and vaginal dryness.

Demographics

Age, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black/African American, Hispanic, other), marital status (married or living with a partner, single), highest education level attained (high school degree or less, some college, or more), annual household income (<$25,000, $25,000–$49,9999, $50,000–$74,999, ≥$75,000), employment status (full-time, part-time, self-employed, unemployed), and possession of health insurance (yes, no) information was collected.

Health characteristics

Exercise (at least once per month, all else), smoking habits (currently smoking, not currently smoking), alcohol consumption (consume alcohol at least once per month, all else), and body mass index (BMI) [underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), obese (≥30 kg/m2), decline to answer] information was also collected. Data were also included on use of hormone therapy (HT) and prescription medications for depression.

Work productivity

Work productivity was measured using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire.17 The WPAI scale is a validated instrument used to measure loss of productivity at work and impairment in daily activities. The questionnaire includes four subscales: absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work impairment, and activity impairment that range from 0% to 100%, with higher values indicating greater impairment.

Absenteeism represents the percentage of work time missed due to health in the past 7 days:

|

Presenteeism represents the percentage of impairment while at work due to health in the past 7 days. This was assessed using a Likert-type item (range: 0–10; anchors: “health problems had no effect on my work,” and “health problems completely prevented me from working,” respectively), which accompanied the question: “during the past seven days, how much did your health problems affect your productivity while you were working?” The score was then multiplied by 10 to give a percentage.

Overall work impairment represents the total percentage of work time missed due to either absenteeism or presenteeism (since those measures are mutually exclusive):

|

Activity impairment represents the percentage of impairment during daily activities. Participants were asked: “During the past seven days, how much did your health problems affect your ability to do your regular daily activities, other than work at a job?” This was accompanied by an 11-point Likert-type item from 0 to 10 and the anchors “health problems had no effect on my daily activities” and “health problems completely prevented me from doing my daily activities.” The score was then multiplied by 10 to arrive at a percentage.

Only employed respondents provided data on absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment, but all respondents provided data on activity impairment.

Health-related quality of life

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured using the SF-8, a multipurpose, generic HRQoL instrument comprising 8 questions, which was developed to be an abbreviated version of the longer SF-36 instrument.18 The current study included the physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores, with a range from 0 to 100 (higher scores indicate better health status). Each of these summary scores is normed to the U.S. population (mean=50, standard deviation [SD]=10).

Healthcare resource utilization

Healthcare utilization in the preceding six months was assessed by the self-reported number of physician visits, the number of emergency room (ER) visits, and the number of days hospitalized.

Statistical analyses

First, comparisons were made between those who reported experiencing menopausal symptoms versus those not reporting menopausal symptoms on demographics, health history, and health outcomes (HRQoL, work productivity, and healthcare resource use). Analysis of variance tests were conducted on continuous variables and omnibus chi-square tests were conducted on categorical variables.

Multivariable analyses were performed to determine whether those who reported experiencing menopausal symptoms differed from those reporting no symptoms on HRQoL, work productivity, and healthcare resource utilization after adjusting for demographic (age, ethnicity, employment, marital status, education, annual household income, and health insurance possession) and health history variables (exercise, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and BMI category), as these variables were significantly different between groups and have been shown in the published literature to influence our dependent variables.19 General linear models were used for HRQoL variables and generalized linear models (GLM) specifying a negative binomial distribution and a log-link function were used for work productivity impairment and resource utilization because of pronounced skew in the data.

Next, among women experiencing menopausal symptoms, all symptoms were simultaneously entered into general linear models (HRQoL) or GLMs (work productivity and resource use) to predict health outcomes to understand the contributions of specific symptoms. All models also controlled for demographic (age, ethnicity, employment, marital status, education, annual household income, and health insurance possession) and health history variables (exercise, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and BMI category).

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1. Two-tailed statistical significance was set a priori as p<0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

The mean age of these women was 49.8 years; 89.0% were white, 67.2% were married, 83.2% had health insurance, and 74.0% had at least some college education (see Table 1). The lifetime prevalence of HT use in the sample was 30.6%, with 11.3% stating they were current users. Depression medication use had a lifetime prevalence of 24.0%, with 17.6% of the sample currently taking antidepressants.

Table 1.

Demographic and Health Characteristic Differences Between Women Experiencing Menopausal Symptoms and Women Not Experiencing Menopausal Symptoms

| Total(N=8,811) | Menopausal symptoms(n=4,116) | No menopausal symptoms(n=4,695) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 49.8±5.9 | 50.3±5.2 | 49.3±6.5 | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 7839 (89.0%) | 3678 (89.4%) | 4161 (88.6%) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 374 (4.2%) | 199 (4.8%) | 175 (3.7%) | |

| Hispanic | 251 (2.8%) | 107 (2.6%) | 144 (3.1%) | |

| Asian | 99 (1.1%) | 28 (0.7%) | 71 (1.5%) | |

| Other race/ethnicity | 179 (2.0%) | 78 (1.9%) | 101 (2.2%) | |

| Missing | 69 | 26 | 43 | |

| Married/living with partner | 5919 (67.2%) | 2963 (72.0%) | 2956 (63.0%) | <0.001 |

| Some college or more | 6522 (74.0%) | 2921 (71.0%) | 3601 (76.7%) | <0.001 |

| Annual household income | 0.004 | |||

| <$25K | 1418 (16.1%) | 690 (16.8%) | 728 (15.5%) | |

| $25K to <$50K | 2588 (29.4%) | 1249 (30.3%) | 1339 (28.5%) | |

| $50K to <$75K | 1858 (21.1%) | 885 (21.5%) | 973 (20.7%) | |

| $75K or more | 2050 (23.3%) | 908 (22.1%) | 1142 (24.3%) | |

| Decline to answer | 897 (10.2%) | 384 (9.3%) | 513 (10.9%) | |

| Employment status | 0.005 | |||

| Full-time employed | 3871 (43.9%) | 1727 (42.0%) | 2144 (45.7%) | |

| Part-time employed | 1066 (12.1%) | 503 (12.2%) | 563 (12.0%) | |

| Self-employed | 681 (7.7%) | 330 (8.0%) | 351 (7.5%) | |

| Unemployed | 3193 (36.2%) | 1556 (37.8%) | 1637 (34.9%) | |

| Health insurance | 7327 (83.2%) | 3376 (82.0%) | 3951 (84.2%) | 0.008 |

| Regularly exercise | 4892 (55.5%) | 2216 (53.8%) | 2676 (57.0%) | 0.003 |

| Current smoker | 2778 (31.5%) | 1479 (35.9%) | 1299 (27.7%) | <0.001 |

| Drink alcohol | 5465 (62.0%) | 2553 (62.0%) | 2912 (62.0%) | 0.998 |

| Body mass index category | <0.001 | |||

| Underweight | 123 (1.4%) | 53 (1.3%) | 70 (1.5%) | |

| Normal weight | 2352 (26.7%) | 1016 (24.7%) | 1336 (28.5%) | |

| Overweight | 2290 (26.0%) | 1117 (27.1%) | 1173 (25.0%) | |

| Obese | 3549 (40.3%) | 1725 (41.9%) | 1824 (38.8%) | |

| Decline to provide weight | 497 (5.6%) | 205 (5.0%) | 292 (6.2%) | |

| Hormone therapy | ||||

| Ever used | 2693 (30.6%) | 1521 (37.0%) | 1172 (25.0%) | <0.001 |

| Currently use | 995 (11.3%) | 568 (13.8%) | 427 (9.1%) | 0.639 |

| Depression medication | ||||

| Ever used | 2119 (24.0%) | 1160 (28.2%) | 959 (20.4%) | <0.001 |

| Currently use | 1548 (17.6%) | 864 (21.0%) | 684 (14.6%) | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Burden of menopausal symptoms

Unadjusted comparisons

A total of 4,116 women (46.7%) reported experiencing at least one of the listed menopausal symptoms (anxiety, decreased interest in sex, depression, forgetfulness, heart racing or pounding, hot flashes, insomnia/difficulty sleeping, joint stiffness, mood changes, night sweats, urine leakage, or vaginal dryness). The remaining 4,695 did not report experiencing any of these symptoms. In comparing these groups, women experiencing symptoms were significantly older, more likely to be non-Hispanic white, less likely to have had some college education, less likely to regularly exercise, more likely to currently smoke, and more likely to have a higher BMI than women not experiencing symptoms (see Table 1).

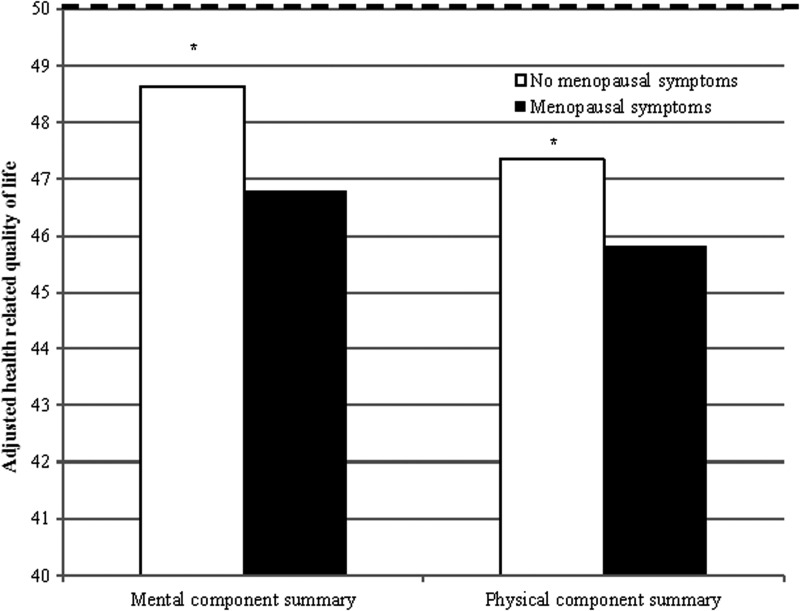

HRQoL

After adjusting for demographic and health characteristic differences, the presence of menopausal symptoms was associated with significantly lower mental (45.8 vs. 47.4, p<0.05) and physical (46.8 vs. 48.6, p<0.05) HRQoL as compared with women not experiencing menopausal symptoms, The adjusted scale scores are displayed in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Adjusted mean levels of health-related quality of life for women experiencing menopausal symptoms with hot flashes and women not experiencing menopausal symptoms and among different menopausal symptom severity levels. *p<0.05; Dotted line represents population norm (mean=50). NHMS, National Health and Wellness Survey.

Productivity and healthcare utilization

Among women currently employed (2,560 women experiencing menopausal symptoms and 3,058 women not experiencing menopausal symptoms), levels of work productivity loss (absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment) were compared adjusting for demographics and health characteristic differences. Women experiencing menopausal symptoms reported significantly higher presenteeism (17.7% vs. 13.6%, p<0.05) and overall work impairment (16.1% vs. 12.3%, p<0.05) than women not experiencing menopausal symptoms. Absenteeism (3.7% vs. 3.4%, p=0.50) was found to be similar between the two groups.

All women provided data on activity impairment and healthcare resource utilization. Women experiencing menopausal symptoms reported significantly higher impairment in daily activities (28.1% vs. 23.3%, p<0.05) and significantly more physician visits in the past six months (2.1 vs. 1.9 p<0.05) than women not experiencing menopausal symptoms. However, the number of ER visits (0.19 vs. 0.17, p=0.05) and hospitalizations (0.24 vs. 0.22, p=0.40) was comparable between those with and without symptoms, respectively.

Burden of specific menopausal symptoms

Additional analyses were conducted to determine the frequency of specific symptoms among those who reported experiencing menopausal symptoms. As reported in Table 2, the most common symptoms were hot flashes (87.4%), night sweats (66.6%), insomnia/difficulty sleeping (60.1%), forgetfulness (49.5%), mood changes (48.3%), and decreased interest in sex (44.7%), all of which were reported by more than 40% of women who were experiencing symptoms. The mean number of symptoms was 4.8 (SD=2.7).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Specific Menopausal Symptoms Among Women Who Experienced Symptoms

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Hot flashes (%) | 3767 | 87.4% |

| Night sweats (%) | 2872 | 66.6% |

| Insomnia/difficulty sleeping (%) | 2591 | 60.1% |

| Forgetfulness (%) | 2135 | 49.5% |

| Mood changes (%) | 2083 | 48.3% |

| Decreased interest in sex (%) | 1927 | 44.7% |

| Joint stiffness (%) | 1703 | 39.5% |

| Anxiety (%) | 1566 | 36.3% |

| Vaginal dryness (%) | 1476 | 34.2% |

| Urine leakage (%) | 1471 | 34.1% |

| Depression (%) | 1400 | 32.5% |

| Heart racing or pounding (%) | 1075 | 24.9% |

| Number of menopausal symptoms | ||

| Mean±SD | 4.8±2.7 | |

These symptoms were then entered into various regression models to predict HRQoL, work productivity loss, and healthcare resource use in order to understand their effect vis-à-vis one another. With respect to humanistic outcomes (HRQoL and activity impairment), depression (b [regression estimate]=6.6 and b=0.19 for MCS and activity impairment, respectively), anxiety (b=−3.3 and b=0.91 for MCS and PCS, respectively), heart racing (b=−1.6 and b=0.15 for PCS and activity impairment, respectively), and forgetfulness (b [regression estimate] = 6.6 and b = 0.19 for MCS and activity impairment, respectively), were the symptoms with the strongest effects (see Table 3). Although joint stiffness was associated with significantly higher levels of overall work impairment (b=0.22), no other symptom was significantly associated with work productivity losses. No symptoms were associated with an increased number of hospitalizations. However, vaginal dryness (b=0.09), depression (b=0.09), and forgetfulness (b=0.09) were all significantly associated with an increased number of physician visits. Similarly, night sweats (b=0.32), mood changes (b=0.29), and depression (b=0.22) were all significantly associated with an increased number of ER visits.

Table 3.

Regression Coefficients of Menopausal Symptoms Predicting Health Outcomes

| |

Mental component summary score |

Physical component summary score |

Activity impairment |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE b | p | b | SE b | p | b | SE b | p | |

| Anxiety | −3.338* | 0.339 | <0.0001 | 0.908* | 0.352 | 0.010 | 0.039 | 0.066 | 0.553 |

| Decreased interest in sex | −1.009* | 0.302 | 0.001 | −0.631* | 0.313 | 0.044 | 0.088 | 0.059 | 0.132 |

| Depression | −6.555* | 0.347 | <0.0001 | −0.061 | 0.360 | 0.865 | 0.185* | 0.066 | 0.005 |

| Forgetfulness | −0.879* | 0.302 | 0.004 | −1.264* | 0.313 | <0.0001 | 0.119* | 0.059 | 0.046 |

| Heart racing or pounding | −0.536 | 0.330 | 0.104 | −1.609* | 0.342 | <0.0001 | 0.152* | 0.064 | 0.018 |

| Hot flashes | 0.269 | 0.415 | 0.517 | −0.130 | 0.431 | 0.763 | −0.017 | 0.082 | 0.831 |

| Insomnia/difficulty sleeping | −0.277 | 0.299 | 0.354 | −0.391 | 0.310 | 0.207 | 0.040 | 0.059 | 0.499 |

| Joint stiffness | 1.421* | 0.303 | <0.0001 | −2.026* | 0.315 | <0.0001 | 0.117* | 0.059 | 0.048 |

| Mood changes | −0.967* | 0.317 | 0.002 | −0.171 | 0.329 | 0.604 | 0.094 | 0.061 | 0.123 |

| Night sweats | −0.444 | 0.300 | 0.139 | −0.704* | 0.311 | 0.024 | 0.078 | 0.059 | 0.189 |

| Urine leakage | 0.118 | 0.306 | 0.699 | −0.976* | 0.317 | 0.002 | 0.104 | 0.060 | 0.081 |

| Vaginal dryness | −0.581 | 0.303 | 0.055 | −0.575 | 0.314 | 0.067 | 0.077 | 0.060 | 0.195 |

| Absenteeism | Presenteeism | Overall work impairment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE b | p | b | SE b | p | b | SE b | P | |

| Anxiety | −0.433 | 0.336 | 0.197 | 0.153 | 0.115 | 0.186 | 0.172 | 0.111 | 0.122 |

| Decreased interest in sex | 0.369 | 0.283 | 0.192 | 0.163 | 0.106 | 0.126 | 0.121 | 0.103 | 0.240 |

| Depression | 0.302 | 0.328 | 0.357 | 0.205 | 0.120 | 0.088 | 0.217 | 0.116 | 0.061 |

| Forgetfulness | 0.268 | 0.268 | 0.318 | 0.168 | 0.107 | 0.114 | 0.155 | 0.102 | 0.130 |

| Heart racing or pounding | 0.247 | 0.296 | 0.404 | 0.141 | 0.117 | 0.227 | 0.120 | 0.113 | 0.286 |

| Hot flashes | −0.033 | 0.378 | 0.932 | 0.162 | 0.148 | 0.274 | 0.181 | 0.143 | 0.206 |

| Insomnia/difficulty sleeping | 0.094 | 0.275 | 0.734 | −0.001 | 0.106 | 0.992 | −0.010 | 0.102 | 0.923 |

| Joint stiffness | −0.174 | 0.268 | 0.517 | 0.176 | 0.106 | 0.098 | 0.218* | 0.102 | 0.034 |

| Mood changes | 0.138 | 0.266 | 0.604 | 0.200 | 0.109 | 0.067 | 0.202 | 0.105 | 0.056 |

| Night sweats | 0.136 | 0.274 | 0.620 | 0.093 | 0.106 | 0.379 | 0.083 | 0.102 | 0.413 |

| Urine leakage | 0.291 | 0.264 | 0.270 | 0.060 | 0.108 | 0.576 | 0.012 | 0.104 | 0.905 |

| Vaginal dryness | −0.013 | 0.284 | 0.965 | 0.092 | 0.109 | 0.403 | 0.083 | 0.106 | 0.436 |

| Physician visits | ER visits | Hospitalizations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE b | p | b | SE b | p | b | SE b | p | |

| Anxiety | 0.033 | 0.029 | 0.267 | 0.119 | 0.111 | 0.285 | −0.120 | 0.227 | 0.595 |

| Decreased interest in sex | 0.021 | 0.026 | 0.419 | −0.034 | 0.102 | 0.738 | −0.157 | 0.202 | 0.437 |

| Depression | 0.088* | 0.030 | 0.003 | 0.218* | 0.111 | 0.049 | 0.212 | 0.224 | 0.346 |

| Forgetfulness | 0.088* | 0.026 | 0.001 | 0.132 | 0.102 | 0.194 | −0.199 | 0.207 | 0.337 |

| Heart racing or pounding | 0.042 | 0.028 | 0.139 | 0.120 | 0.106 | 0.258 | −0.002 | 0.223 | 0.994 |

| Hot flashes | 0.014 | 0.037 | 0.697 | 0.252 | 0.154 | 0.101 | 0.071 | 0.282 | 0.800 |

| Insomnia/difficulty sleeping | 0.002 | 0.026 | 0.946 | −0.018 | 0.102 | 0.858 | 0.068 | 0.197 | 0.729 |

| Joint stiffness | 0.013 | 0.027 | 0.635 | −0.158 | 0.101 | 0.117 | −0.328 | 0.198 | 0.098 |

| Mood changes | −0.007 | 0.028 | 0.797 | 0.285* | 0.107 | 0.008 | 0.393 | 0.215 | 0.067 |

| Night sweats | 0.073* | 0.027 | 0.006 | 0.319* | 0.106 | 0.003 | 0.361 | 0.208 | 0.083 |

| Urine leakage | 0.048 | 0.026 | 0.072 | 0.204* | 0.100 | 0.042 | 0.214 | 0.208 | 0.303 |

| Vaginal dryness | 0.094* | 0.026 | <0.001 | 0.038 | 0.100 | 0.703 | −0.012 | 0.200 | 0.954 |

All models controlled for age, ethnicity, employment, marital status, education, annual household income, health insurance possession, exercise, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and BMI category. *p<0.05.

b, regression estimate; SE b, standard error of the regression estimate.

Discussion

The objective of the current study was to assess the burden of menopausal symptoms collectively and individually. The 2005 NHWS data were identified for this study because it was the most recent survey that included questions relating to menopausal symptoms. Given that few changes in the management or treatment of menopause have occurred since this time, the results from this study should still remain current.

Previous studies have demonstrated an impact of menopausal symptoms on HRQoL across a variety of cultures and measures.6–13 Our analysis provides further confirmation that women who experience menopausal symptoms exhibit impaired HRQoL compared to those who report no symptoms of menopause. Compared with women without menopausal symptoms, women with menopausal symptoms were observed to have approximately 2-point decrements in the mental and physical component summaries of the SF-8, which approaches what may be considered clinically meaningful.20 The results also suggest that depression and anxiety are two symptoms with the largest effects on mental HRQoL and joint stiffness and heart palpitations are two symptoms with largest effects on physical HRQoL.

This study is further unique in utilizing a validated instrument to measure the impact of menopausal symptoms on health-related work impairment, which enabled us to quantify the economic burden of these symptoms. Women with menopausal symptoms reported significantly higher work impairment and significantly more resource use. However, among women with symptoms, no specific symptom significantly predicted work productivity losses (aside from joint stiffness and overall work impairment, which exhibited a small effect). This finding suggests that the presence of a constellation of menopausal symptoms is associated with productivity loss rather than a specific symptom.

Although no differences in hospitalizations or ER visits were observed between women with and without menopausal symptoms, women with symptoms did report significantly more physician visits. This is generally consistent with previous findings from the STRIDE study, which found greater healthcare resource use and direct cost differences for women who were experiencing hot flashes.14 This discrepancy may be due to differences in the focus (menopausal symptoms generally vs. hot flashes), sample (larger representative sample vs. single internal medicine practice) or modeling. It is also possible because of the results of the Women's Health Initiative study, which uncovered several long-term consequences of HT,21 women became less willing to take HT and/or, perhaps, less likely to visit with their physician. Instead, women may be more likely to explore alternative treatment options rather than traditional medicine, though further research is necessary to test these hypotheses.

Regardless, these results suggest a pervasive burden of menopausal symptoms across a wide array of health outcomes. Given the prevalence of these symptoms (46.7% of women experienced symptoms with an average of 5 symptoms), and the size of their impact on HRQoL, the ability to work, resource use, and societal costs, more emphasis on the treatment of these symptoms, particularly for those that are considered severe, by physicians may have an important humanistic and economic impact.

Limitations

NHWS data is self-reported so recall bias may have introduced additional measurement error. Further, the NHWS was not designed with this particular research question in mind and, therefore, did not include all variables of interest. For example, the presence of surgical menopause was unknown among our sample. Similarly, distinctions between peri-menopause and post-menopause were not made explicitly and it was unclear at what point each women was in the menopause transition. The NHWS was also cross-sectional, so causality cannot be inferred. Although menopausal symptoms were considered as predictors of worse HRQoL, work productivity, and healthcare resource use it is possible that these relationships may be explained by unmeasured confounding variables. Indeed, a number of conditions can cause symptoms similar to those of menopause and these conditions may explain part of the associations observed here. Several covariates also used a fairly coarse definition (e.g., no exercise versus regular exercise) and a finer definition could have possible explained additional variability in the outcomes. Although participants from the NHWS are demographically representative to the US population, it is possible that the sample from the current study and the population of women experiencing menopause differs meaningfully. These differences might influence the extent to which the results can be generalized.

Conclusions

These findings suggest there is a humanistic and economic burden for women who reported experiencing menopausal symptoms. The results underscore the need for improved management of menopausal symptoms.

Disclosure Statement

The National Health and Wellness Survey was conducted by Kantar Health (New York, NY). Pfizer, Inc. purchased access to the NHWS dataset and funded the analysis. Dr. DiBonaventura and Mr. Wagner are employees of Kantar Health. Drs. Whiteley, Alvir, and Shah are employees of Pfizer, Inc.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health (NIH) State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on management of menopause-related symptoms. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2005;22:1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Census Bureau. Population estimates (Sex by Age) 2008. http://factfinder2.census.gov http://factfinder2.census.gov

- 3.Hvas L. Positive aspects of menopause: a qualitative study. Maturitas. 2001;39:11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(01)00184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berecki-Gisolf J. Begum N. Dobson AJ. Symptoms reported by women in midlife: Menopausal transition or aging? Menopause. 2009;16:1021–1029. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a8c49f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman BM. Voda A. Gronseth E. The prevalence of hot flash and associated variables among perimenopausal women. Res Nurs Health. 1985;8:261–268. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770080308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams RE. Kalilani L. DiBenedetti DB. Zhou X. Fehnel SE. Clark RV. Healthcare seeking and treatment for menopausal symptoms in the United States. Maturitas. 2007;58:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karaçam Z. Seker SE. Factors associated with menopausal symptoms and their relationship with the quality of life among Turkish women. Maturitas. 2007;58:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avis NE. Ory M. Matthews KA, et al. Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of middle- aged women: Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Med Care. 2003;41:1262–1276. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093479.39115.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avis NE. Colvin A. Bromberger JT, et al. Change in health-related quality of life over the menopausal transition in a multiethnic cohort of middle-aged women: Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) menopause. 2009;16:860–869. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a3cdaf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantril H. The pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallicchio L. Miller S. Zacur H. Flaws JA. Race and health-related quality of life in midlife women in Baltimore, Maryland. Maturitas. 2009;63:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams RE. Levine KB. Kalilani L. Lewis J. Clark RV. Menopause-specific questionnaire assessment in US population-based study shows negative impact on health-related quality of life. Maturitas. 2009;62:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daly E. Gray A. Barlow D. McPherson K. Roche M. Vessey M. Measuring the impact of menopausal symptoms on quality of life. BMJ. 1993;307:836–840. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6908.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hess R. Chang C-C. Ness RB. Hays RD. Kapoor WN. Bryce CL. The associations of menopause and health-related quality of life with health services utilization: Results from the STRIDE study. Abstract presented at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Society of Medical Decision Making; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Oct 24–27;2010 . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavigne JE. Griggs JJ. Tu XM. Lerner DJ. Hot flashes, fatigue, treatment exposures and work productivity in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:296–302. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0072-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiBonaventura M. Wagner J-S. Yuan Y. L'Italien G. Langley P. Kim WR. Humanistic and economic impacts of hepatitis C in the United States. J Med Econ. 2010;13:709–718. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2010.535576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reilly MC. Zbrozek AS. Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353–365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE. Kosinksi M. Dewey JE. Gandek B. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2001. How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: A manual for users of the SF-8 Health Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiBonaventura MD. Wagner JS. Alvir J. Whiteley J. Depression, quality of life, work productivity, resource use, and costs among women experiencing menopause and hot flashes. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012 doi: 10.4088/PCC.12m01410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hays RD. Morales LS. The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Annals of Medicine. 2001;33:350–357. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chlebowski R. Hendrix SL. Langer RD, et al. Influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy postmenopausal women: The Women's Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3243–3253. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.24.3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]