Abstract

Bartonella bacilliformis is the etiological agent of a life-threatening illness. Thin blood smear is the most common diagnostic method for acute infection in endemic areas of Peru but remains of limited value because of low sensitivity. The aim of this study was to adapt a B. bacilliformis-specific real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for use with dried blood spots (DBS) as a sampling method and assess its performance and use for the diagnosis and surveillance of acute Bartonella infection. Only two of 65 children (3%) that participated in this study had positive blood smears for B. bacilliformis, whereas 16 (including these two) were positive by PCR performed on DBS samples (24.6%). The use of DBS in combination with B. bacilliformis-specific PCR could be a useful tool for public health in identifying and monitoring outbreaks of infection and designing control programs to reduce the burden of this life-threatening illness.

Introduction

Bartonella bacilliformis is the etiological agent of a life-threatening bacterial illness “Carrion's disease” or human bartonellosis, which occurs in the inter-Andean regions of Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia, with sporadic cases in Bolivia and Chile1; this neglected infectious disease is thought to be transmitted by the sand-fly Lutzomyia verrucarum. Climate change influences the geographical distribution and is associated with outbreaks, as seen with El Niño.2 Infection is biphasic with acute infection, causing severe anemia and fever, known as Oroya fever, and a chronic infection causing skin manifestations (verruga peruana). Relatively little is known about the epidemiological situation other than that incidence appears to be both geographically and temporally focal. One study, dating back from 2002, indicated an incidence of 12.7/100 person years in a Peruvian mountain valley community, with highest rates in children < 5 years of age.3

Thin blood smear is the most common diagnostic method for Oroya fever in endemic areas of Peru but remains of limited value caused by low sensitivity. Diagnosis is therefore usually clinical. Although sensitive serological assays for the detection of chronic infection have been developed,4 no suitable diagnostic methods currently exist for the detection of acute B. bacilliformis infection. The DNA-based detection methods currently available require restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis or reverse line blotting to differentiate Bartonella species,5,6 which are labor intensive, slow, and complex procedures.

The aim of this study was to adapt a B. bacilliformis-specific real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for use with dried blood spots (DBS) and assess its performance and use for the diagnosis and surveillance of acute Bartonella infection.

Methods

Between November 2011 and July 2012, febrile children (temperature ≥ 37.5°C) ≤ 10 years of age presenting at two outpatient clinics in the Yautan region of Peru were recruited, after written consent of parents or guardians was obtained. Yautan region was chosen as a study site because it is believed by the local population to be an endemic region for bartonellosis. As part of the routine clinical services, blood smears were collected by finger or heel prick for diagnosis of B. bacilliformis. For this study, capillary blood was collected directly onto filter paper (Whatman 903, GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) after the blood smear from the same finger prick. These DBS were dried and stored at room temperature and individually packed with desiccants in a ziplock bag. Blood smears were microscopically examined at the clinic and subsequently at the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (UPCH). The DBS samples were shipped once a month to Leiden Cytology and Pathology Laboratory in The Netherlands, where DNA was extracted from one DBS spot (12 mm circle) with spin columns (QiAmp DNA blood minikit, Hilden, Germany). Manufacturer's instructions were followed except that a 12 mm instead of a 3 mm DBS spot was processed. The DBS eluates were tested using a B. bacilliformis-specific real-time PCR, based on the Bartonella generic primers targeting 16S–23S rRNA intergenic transcribed spacer region, described previously5; the reverse primer and probe were developed in this study, whereas the forward primer remained the same as published previously5. The PCR was performed in a 50 µL total reaction volume with 500 nM forward (5′-TTGATAAGCGTGAGGTCGGAGG-3′), 500 nM reverse (5′-GCAACCACACATAGTAAGCCTAA-3′), 250 nM reverse (FAM- ATGTCTGCCTAGAAATCAATCATAGGCC-bbq), 10 μL H2O, and 15 μL DBS DNA. Real-time PCR was performed with the Quantitect virus kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) in a LightCycler 480 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with the following cycle conditions: 95°C for 15 minutes, 60 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, and 30 seconds at 60°C. The PCR was performed with positive spiked DBS samples (strain obtained from Health Protection Agency, London, UK; NCTC 12134) and negative controls (water) in each run.

To confirm the specificity of the Real-Time PCR product, the 105 basepair (bp) fragment from the Bartonella generic PCR developed by Garcia-Esteban and others5 performed on DBS DNA extract was used to amplify a product for sequencing. Sequencing reaction was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (10 μL reactions) (Abi BigDye V3.1, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and analyzed by ABI 7300 according to manufacturer's recommendations. Sequences were viewed and aligned in Geneious 5.6 software (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand).

Ethical approval for this study was obtained at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and UPCH.

Results

Sixty-five febrile children presenting at two clinics in Yautan province were included in the study. The average age was 4.1 years (range 1–10) and 31 of the 65 children (48%) were male with an average temperature of 38.3°C (37–39.5°C) upon arrival at the clinic. The time between onset of fever and arrival at the clinic varied from 1 to 5 days, with an average of 2.4 days.

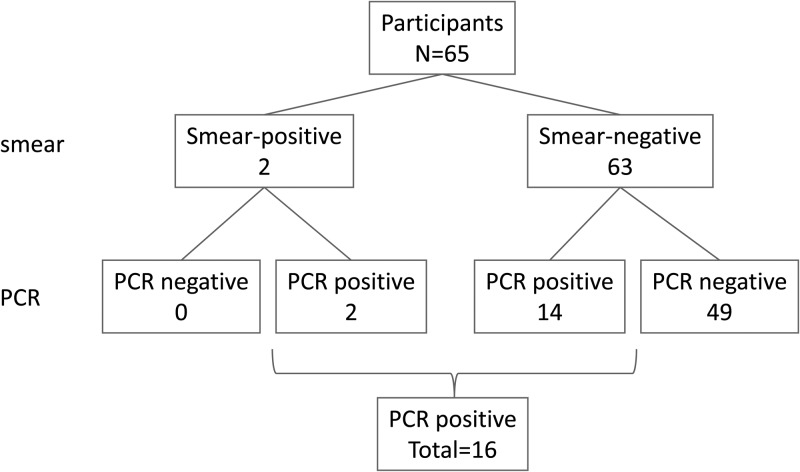

Only two of 65 children (3%) that participated in this study had positive blood smears for B. bacilliformis, whereas 16 were positive by PCR performed on DBS samples (24.6%) (Figure 1). All samples were extracted and tested twice. The internal PCR positive and negative controls performed as expected in all experiments. To confirm that B. bacilliformis was detected, sequencing was performed. The two positive blood smear samples and an additional two PCR positive were successfully sequenced showing 100% match with strain KC583 (NCBI:CP000524).

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of test results for blood smear and real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) performed on dried blood spots (DBS) samples.

Even though blood smears are known to have low sensitivity, they are still commonly used in Peru and therefore used as a reference in this study. Using blood smears as a comparator, the sensitivity and specificity of the PCR with DBS samples was 100% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 34–100%) and 78% (95% CI: 66–86%), respectively. Sequence results indicate however that at least two samples negative by blood smears, were in fact positive for B. bacilliformis.

Discussion

In certain regions of Peru human bartonellosis is endemic, but outbreaks have been reported in non-endemic regions7,8; the method developed in this study could be a useful surveillance tool for endemic regions and particularly for outbreak investigations. The DBS obviates the need for cold chain transportation requirements and thus greatly simplifies sample collection strategies for surveillance or outbreak investigations in remote settings. The DBS requires a small sample volume and minimal technical expertise to prepare, making this an acceptable and cost-effective method of collecting blood samples.

Although sample size of our study is small, screening with DBS and PCR appears to be a reliable, sensitive, and specific method for the diagnosis of bartonellosis. The two B. bacilliformis positive cases that were detected by blood smear were severely ill children with anemia (< 3 gm/dL) and had a very high bacterial load in the blood stream (> 100.000 c/mL). The low sensitivity of blood smears found in this study is in line with other studies.9 Four of the 16 positive samples were sequenced, which were confirmed by gene sequence as B. bacilliformis.

The DBS samples can also be used for further analyses, such as monitoring quinolone resistance and, given the recent discovery of Bartonella rochalimae causing illness related to Oroya fever, to differentiate between Bartonella species.10–12 Recent advances in the development of simpler nucleic acid amplification and sequencing assays have enabled these assays to be more widely available in the developing world. The use of DBS samples in combination with pathogen-specific nucleic acid amplification assays such as PCR could be a useful tool for disease control programs in identifying and monitoring disease outbreaks and designing strategies to reduce the burden of bartonellosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all study participants and clinicians for their participation in this study. Additionally, the authors thank Cesar Ugarte-Gil, Nelson Solórzano, Nuria Sanchez Clemente, Gisela Henriques, Joyce Holierhoek, and Mathilde Boon for their contribution to the study.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was funded by the UBS Optimus Foundation.

Authors' addresses: Pieter W. Smit, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland, E-mail: Pieter.smit@lshtm.ac.uk. Rosanna W. Peeling, David Moore, and David Mabey, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK, E-mails: Rosanna.peeling@lshtm.ac.uk, David.moore@lshtm.ac.uk, and David.mabey@lshtm.ac.uk. Patricia J. Garcia, Lorena L. Torres, and José E. Pérez-Lu, Epidemiology, STI/AIDS Unit, School of Public Health, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru, E-mails: patricia.garcia@upch.pe, lorenalotogu@gmail.com, and jose.perez.l@upch.pe.

Reprint requests: David Mabey, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, WC1E 7HT, UK, E-mail: David.mabey@lshtm.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Sanchez Clemente N, Ugarte-Gil CA, Solorzano N, Maguina C, Pachas P, Blazes D, Bailey R, Mabey D, Moore D. Bartonella bacilliformis: a systematic review of the literature to guide the research agenda for elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1819. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chinga-Alayo E, Huarcaya E, Nasarre C, del Aguila R, Llanos-Cuentas A. The influence of climate on the epidemiology of bartonellosis in Ancash, Peru. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2004;98:116–124. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(03)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chamberlin J, Laughlin LW, Romero S, Solorzano N, Gordon S, Andre RG, Pachas P, Friedman H, Ponce C, Watts D. Epidemiology of endemic Bartonella bacilliformis: a prospective cohort study in a Peruvian mountain valley community. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:983–990. doi: 10.1086/344054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamberlin J, Laughlin L, Gordon S, Romero S, Solorzano N, Regnery RL. Serodiagnosis of Bartonella bacilliformis infection by indirect fluorescence antibody assay: test development and application to a population in an area of bartonellosis endemicity. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4269–4271. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4269-4271.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Esteban C, Gil H, Rodriguez-Vargas M, Gerrikagoitia X, Barandika J, Escudero R, Jado I, Garcia-Amil C, Barral M, Garcia-Perez AL, Bhide M, Anda P. Molecular method for Bartonella species identification in clinical and environmental samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:776–779. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01720-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norman AF, Regnery R, Jameson P, Greene C, Krause DC. Differentiation of Bartonella-like isolates at the species level by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism in the citrate synthase gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1797–1803. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1797-1803.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huarcaya E, Maguina C, Torres R, Rupay J, Fuentes L. Bartonelosis (Carrion's Disease) in the pediatric population of Peru: an overview and update. Brazilian J Infect Dis. 2004;8:331–339. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702004000500001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis BA, Rotz LD, Leake JA, Samalvides F, Bernable J, Ventura G, Padilla C, Villaseca P, Beati L, Regnery R, Childs JE, Olson JG, Carrillo CP. An outbreak of acute bartonellosis (Oroya fever) in the Urubamba region of Peru, 1998. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:344–349. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pachas P. Value diagnosis of the thin Smear in Human bartonellosis (Carrion's disease). American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 53rd Annual Meeting; Miami Beach, FL: ASTMH; 2004. p. 300. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wormser GP. Discovery of new infectious diseases—bartonella species. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2346–2347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.del Valle LJ, Flores L, Vargas M, Garcia-de-la-Guarda R, Quispe RL, Ibanez ZB, Alvarado D, Ramirez P, Ruiz J. Bartonella bacilliformis, endemic pathogen of the Andean region, is intrinsically resistant to quinolones. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e506–e510. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaloner GL, Palmira V, Birtles RJ. Multi-locus sequence analysis reveals profound genetic diversity among isolates of the human pathogen Bartonella bacilliformis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]