Abstract

Objectives

Among hospice patients who lived in nursing homes, we sought to: (1) report trends in hospice use over time, (2) describe factors associated with very long hospice stays (>6 months), and (3) describe hospice utilization patterns.

Design, setting, and participants

We conducted a retrospective study from an urban, Midwest cohort of hospice patients, aged ≥65 years, who lived in nursing homes between 1999 and 2008.

Measurements

Demographic data, clinical characteristics, and health care utilization were collected from Medicare claims, Medicaid claims, and Minimum Data Set assessments. Patients with overlapping nursing home and hospice stays were identified. χ2 and t tests were used to compare patients with less than or longer than a 6-month hospice stay. Logistic regression was used to model the likelihood of being on hospice longer than 6 months.

Results

A total of 1452 patients received hospice services while living in nursing homes. The proportion of patients with noncancer primary hospice diagnoses increased over time; the mean length of hospice stay (114 days) remained high throughout the 10-year period. More than 90% of all patients had 3 or more comorbid diagnoses. Nearly 20% of patients had hospice stays longer than 6 months. The hospice patients with stays longer than 6 months were observed to have a smaller percentage of cancer (25% vs 30%) as a primary hospice diagnosis. The two groups did not differ by mean cognitive status scores, number of comorbidities, or activities of daily living impairments. The greater than 6 months group was much more likely to disenroll before death: 33.9% compared with 13.8% (P < .0001). A variety of patterns of utilization of hospice across settings were observed; 21 % of patients spent some of their hospice stay in the community.

Conclusions

Any policy proposals that impact the hospice benefit in nursing homes should take into account the difficulty in predicting the clinical course of these patients, varying utilization patterns and transitions across settings, and the importance of supporting multiple approaches for delivery of palliative care in this setting.

Keywords: Hospice, nursing home, utilization, policy

In the United States, about 1.5 million people live in nursing homes, and nearly 1 in 4 Americans die in the nursing home setting.1,2 Despite quality improvement efforts by facilities and extensive government regulations, the quality of nursing home care varies widely.3 Palliative care, in particular, including goals of care discussions and symptom management, has been found to be suboptimal in the nursing home setting.4–8 The Medicare hospice benefit, which provides palliative care for terminally ill patients, is the predominant avenue through which nursing home patients receive specialized end-of-life care services. Hospice has been demonstrated to improve quality of care outcomes for patients dying in nursing homes, including improved pain management, reduced hospitalizations, and improved family satisfaction.9–13

Use of the hospice benefit has grown dramatically over the past few decades: Approximately 40% of Medicare enrollees die while receiving hospice services.14–16 About one third of all hospice patients live in nursing homes.15 On average, nursing home hospice patients tend to have longer lengths of stay compared with hospice patients living in the community. Patients with longer hospice stays and more clinically stable courses tend to be more profitable to hospice providers because Medicare reimburses hospice on a per diem basis.17

Increasing attention is being focused on nursing home hospice patients because of the growth of hospice in this setting.18 The Medicare hospice benefit is designed for patients with terminal disease who have an anticipated life expectancy of ≤6 months. Policymakers have expressed concern that some nursing home patients who are on hospice do not meet these eligibility criteria.18 Nursing home hospice patients are less likely to have cancer as their primary diagnosis and more likely to have diagnoses such as dementia.19 It can be difficult for physicians to predict life expectancy even in the setting of advanced dementia.8 Although policymakers are concerned about overuse of hospice, advocates are concerned about potential underuse of both hospice and palliative care services in the nursing home setting.13

This study was undertaken to better understand the patterns of use of hospice among nursing home patients. Using a unique dataset of more than 30,000 adults older than 65 years, we describe patterns of nursing home hospice use over a 10-year period. In this study, we sought to: (1) report trends in hospice use over time, (2) describe factors associated with very long hospice stays (>6 months), and (3) describe hospice utilization patterns of older adults who used hospice while living in nursing homes. In addition to our interest in describing broad patterns of utilization, we hypothesized that we would see increasing lengths of stay for nursing home hospice patients over the time period studied. Furthermore, we hypothesized that patients with longer hospice stays would have different clinical characteristics and hospice utilization patterns in comparison with patients with shorter stays, which might explain these longer stays.

Methods

Overview

This study, including waiver of patient consent, was approved by the Indiana University Purdue University— Indianapolis Institutional Review Board and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Privacy Board. For this analysis of nursing home hospice patients, we used a merged dataset of Medicare claims, Indiana Medicaid claims, Minimum Data Set (MDS), Outcome Assessment and Information Set, and the local electronic medical record system.20 All patients included in this database had at least one clinical encounter within Wishard Health Services, an urban public health system serving medically indigent patients in Indianapolis. Wishard Health Services includes a 350-bed hospital and a network of 8 primary care centers in Indianapolis. It has a Senior Care program staffed by faculty in an academic geriatric medicine program.21 Although patients were initially enrolled at Wishard, the Medicare, Indiana Medicaid, MDS, and Outcome Assessment and Information Set data capture the patients’ utilization for all other providers and hospitals.

Sample

Data were collected over an 11-year period (1999—2009) on 33,387 patients aged ≥65 years. Subjects who had a clinical encounter with Wishard were enrolled if they turned 65 years old at any time between 1999 and 2008 and were matched to Medicare claims by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services using name, social security number, and birthdate. Patients with hospice and nursing home overlapping episodes were identified using Medicare and Indiana Medicaid claims and MDS assessments. To be included in the nursing home hospice cohort, patients had to have a hospice admission date between January 1, 1999, and December 31, 2008. Hospice length of stay was characterized as a period of continuous hospice enrollment. For those patients with more than one episode of nursing home care, we used only the last nursing home stay.

Data Collection

Measures collected for analysis included demographics, co-morbidities, and health care utilization. Demographics consisted of age, sex, race/ethnicity, and Medicare/Medicaid dual eligibility based on claims data at time of hospice enrollment. Medicare and Medicaid International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes present in claims files at the time of hospice enrollment were used to measure comorbidity with indicators of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, arthritis, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and stroke. Two measures of activities of daily living function and cognitive performance were taken from the MDS assessment closest to hospice enrollment to augment these measures of comorbidity. Primary diagnosis of the hospice stay was also included as an independent variable. Primary hospice diagnosis categories included dementia, failure to thrive, heart disease, lung disease, cancer, or “"other. ” Utilization, including hospital, hospice, and nursing home use, was derived from Medicare and Medicaid claims. Hospice stays longer than 6 months (>180 days) were a key outcome of interest.

Analysis

After defining a nursing home hospice cohort, we examined descriptive statistics of trends over time in hospice use and patient characteristics. For the second aim of the study, subjects were grouped based on hospice length of stay. Nursing home hospice patients were considered “long stay” if they were enrolled in hospice for longer than 6 months (>180 days) versus if they were enrolled in hospice for ≤6 months (≤180 days). χ2 and t tests were used to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in the two hospice length-of-stay groups. Logistic regression analysis22 was used to model the likelihood of being a long-stay hospice patient (ie. hospice length of stay > 180 days). For the third aim, based on the start dates of the hospice claim and the nursing home stay, we sorted the nursing home hospice cohort into groups: hospice stay completely within a nursing home stay, enrolling in hospice in the community and then entering a nursing home, enrolling in hospice while in a nursing home and transferring to the community, and moving from the community to the nursing home and back to the community while on hospice. Relative frequencies of these specific patterns were reported.

Results

Of the 33,387 patients in the entire sample, 32% (10,556 patients) lived in a nursing home for some period between 1999 and 2008; 11% (3771 patients) used hospice. Of the total sample, 10,225 (31%) died during the study period. Among the patients in this sample who ever used hospice, 39% were living in nursing homes for at least some part of their hospice stay, resulting in a cohort of 1452 nursing home hospice patients. Approximately 40% of the nursing home hospice patients were African-American, and three fourths were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Overall, 71% of all nursing home hospice patients had a noncancer hospice diagnosis. The overall mean length of stay on hospice among these nursing home patients was 114 days (median 36 days). About 92% of all nursing home hospice patients had 3 or more comorbid diagnoses; a high degree of cognitive and functional impairment was also observed. Additional demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Population: Nursing Home Hospice Patients by Hospice Length of stay

| Characteristics | Total (N = 1452) | Hospice Length of Stay | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <180 days (n= 1166) | >180 days (n = 286) | |||

| Age at hospice enrollment, y, mean (SD) | 81.2 (8.2) | 81.2 (8.1) | 80.9 (8.5) | .4856 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 544 (37.5) | 447 (38.3) | 97 (33.9) | .1664 |

| White race, n (%) | 870 (59.9) | 692 (59.4) | 178 (62.2) | .3716 |

| ADL impairments, mean (SD)* | ||||

| Categorical indicators | 16.2 (6.4) | 16.3 (6.3) | 15.6 (6.6) | .1120 |

| Binary indicators | 5.0 (1.7) | 5.0 (1.6) | 4.8 (1.8) | .1245 |

| CPS score, mean (SD)* | 2.9 (1.8) | 2.9 (1.8) | 2.7 (1.8) | .1259 |

| CPS score = 5 or 6, n (%)* | 252 (18.2) | 206 (18.6) | 46 (16.6) | .4326 |

| Dual-eligible Medicaid/Medicare, n (%) | 1091 (75.1) | 877 (75.2) | 214 (74.8) | .8914 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Dementia | 1091 (75.1) | 874 (75.0) | 217 (75.9) | .7478 |

| Cancer | 817 (56.3) | 661 (56.7) | 156 (54.6) | .5125 |

| CAD | 947 (65.2) | 778 (66.7) | 169 (59.1) | .0152 |

| CHF | 884 (60.9) | 726 (62.3) | 158 (55.2) | .0293 |

| Hypertension | 1306 (89.9) | 1058 (90.7) | 248 (86.7) | .0426 |

| Arthritis | 982 (67.6) | 788 (67.6) | 194 (67.8) | .9353 |

| Diabetes | 822 (56.6) | 676 (58.O) | 146 (51.1) | .0342 |

| COPD | 864 (59.5) | 698 (59.9) | 166 (58.0) | .5740 |

| Stroke | 377 (26.0) | 310 (26.6) | 67 (23.4) | .2747 |

| Renal disease | 63 (4.3) | 56 (4.8) | 7 (2.5) | .0798 |

| Liver disease | 244 (16.8) | 206 (17.7) | 38 (13.3) | .0758 |

| >3 comorbidities | 1374 (94.6) | 11 07 (94.9) | 267 (93.4) | .2872 |

| Length of stay on hospice, days, mean (SD); median | 114.1 (196.0); 36 | 40.8 (45.7); 20 | 412.9 (274.9); 331 | <.0001 |

| Disenrollment before death, n (%) | 258 (17.8) | 161 (13.8) | 97 (33.9) | <.0001 |

| On hospice before NH admittance, n (%) | 208 (14.3) | 125 (10.7) | 83 (29.0) | <.0001 |

| Days in NH before hospice enrollment, mean (SD); median† | 756.4 (968.8); 400.5 | 708.8 (958.0); 309 | 1000.3 (989.4); 836 | <.0001 |

| Long-stay NH patients (>90 days), n (%) | 936 (64.5) | 759 (65.1) | 177 (61.9) | .3100 |

| Hospital stay in prior year to hospice, n (%) | 1080 (74.4) | 898 (77.0) | 182 (63.6) | <.0001 |

| Primary hospice diagnosis, n (%) | .0379 | |||

| Cancer | 423 (29.1) | 351 (30.1) | 72 (25.2) | |

| Dementia | 321 (22.1) | 249 (21.4) | 72 (25.2) | |

| Failure to thrive | 145 (10.0) | 108 (9.3) | 37 (12.9) | |

| Heart disease | 126 (8.7) | 104 (8.9) | 22 (7.7) | |

| Lung disease | 116 (8.O) | 86 (7.4) | 30 (10.5) | |

| Other | 321 (22.1) | 268 (23.0) | 53 (18.5) | |

| Hospice admission year, n (%) | .6586 | |||

| 1999–2000 | 83 (5.7) | 71 (6.1) | 12 (4.2) | |

| 2001–2002 | 180 (12.4) | 142 (12.2) | 38 (13.3) | |

| 2003–2004 | 331 (22.8) | 270 (23.2) | 61 (21.3) | |

| 2005–2006 | 423 (29.1) | 339 (29.1) | 84 (29.4) | |

| 2007–2008 | 435 (30.0) | 344 (29.5) | 91 (31.8) | |

χ2 test was used to make comparisons on categorical variables; t test was used for continuous variables.

ADL, activities of daily living; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CPS, cognitive performance scale; NH, nursing home.

Seventy cases were missing on CPS; 148 were missing on ADL scale.

Two hundred and eight cases where subject was on hospice before NH admission were excluded from calculation.

Time Trends

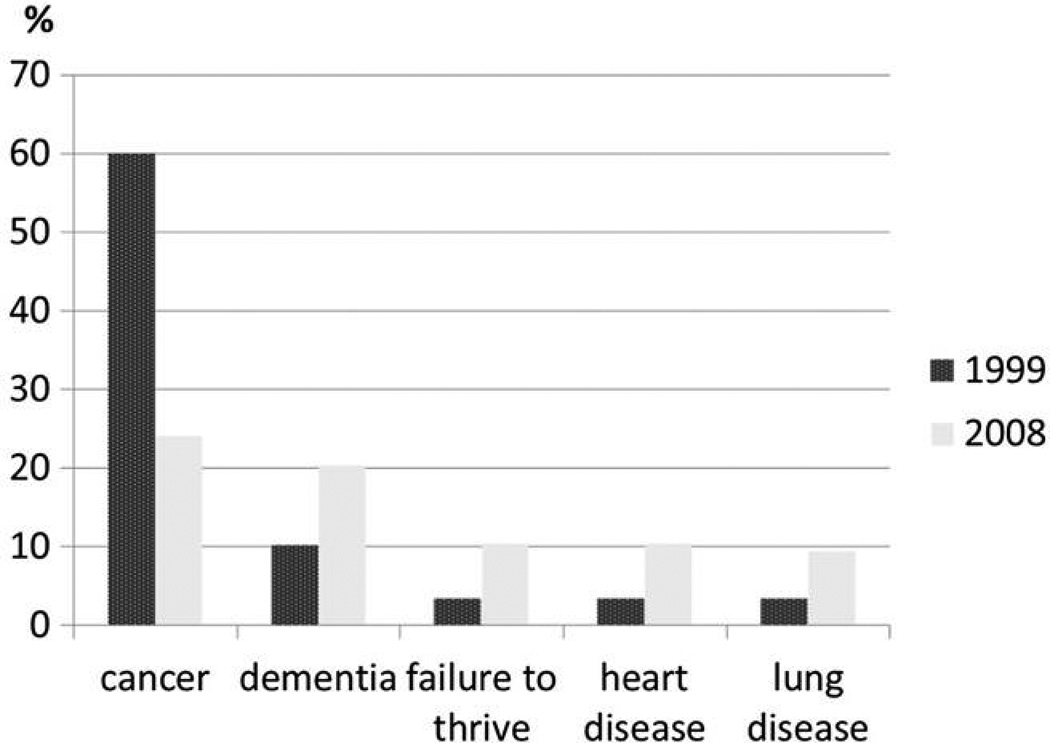

Cancer was the largest single category for primary hospice diagnosis throughout the 10-year study period in the nursing home hospice cohort: 423 (29%) of the 1452 patients (Table 1). However, the proportion of primary hospice diagnoses of cancer among nursing home hospice patients decreased over time from 60% in 1999 to 24% in 2008. Dementia was the next most frequent diagnosis among nursing home hospice patients (22% overall for the 10-year period), although dementia was the most common diagnosis in 2003 and 2005. Primary hospice diagnosis categories of failure to thrive, heart disease, and lung disease also increased over time (Figure 1). The mean length of stay was consistent over the 10-year study period; no upward trend was observed despite the changing patterns of primary diagnosis. About 23% of nursing home hospice patients had hospice stays of ≤7 days.

Fig. 1.

Primary hospice diagnoses over a 10-year period.

Characteristics of Nursing Home Hospice Patients with Less Than and Greater Than 6-Month Stays

There were 286 (19.7%) nursing home hospice patients with a hospice stay of longer than 6 months (Table 1). Nearly 48% of patients had a hospice stay shorter than 30 days. The greater than and less than 6-month hospice stay groups differed by primary hospice diagnoses (P = .0379). The longer than 6-month stay hospice patients were observed to have a slightly larger percentage of dementia (25% vs 21 %), failure to thrive (13% vs 9%), and lung disease (11% vs 7%) diagnoses; and a smaller percentage of cancer (25% vs 30%) and other primary hospice diagnoses (19% vs 23%). Patients with hospice stays ≤6 months had greater proportions of congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes diagnoses than long-stay hospice patients. The two groups did not differ by mean cognitive status scores, number of comorbidities, or activities of daily living impairments. The long-stay group had greater rates of disenrollment before death: 33.9% compared with 13.8% (P < 0.0001; Table 1).

In the multivariable analysis, having enrolled in hospice care before transfer to the nursing home was a significant predictor of hospice use longer than 6 months (odds ratio [OR] = 5.00, 95% CI: 3.22–7.77, P < .0001; Table 2). Compared with a primary diagnosis of cancer, hospice diagnoses of failure to thrive (OR = 2.19, 95% CI: 1.22–3.93, P = .0091), dementia (OR = 1.88, 95% CI: 1.10–3.21, P = .0205), and lung disease (OR = 1.87, 95% CI: 1.02–3.44, P = .0426) were also associated with long-stay hospice use. Hospitalization in the year before enrollment in hospice was associated with a hospice stay of ≤6 months (OR = 0.60, 95% CI: 0.44–0.83, P = .0018). Demographic and clinical characteristics, including evidence of advanced cognitive impairment (cognitive performance scale score = 5 or 6), were not significant independent predictors of long-stay hospice use. The estimated area under the receiver operator characteristic curve for this model was 0.674.

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Long Hospice Stay (>180 days) Among Nursing Home Patients (N = 1303)

| Factors | Estimate | SE | Wald χ2 | OR (95%CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at hospice enrollment | −0.012 | 0.010 | 1.40 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | .2372 |

| Male sex | −0.219 | 0.164 | 1.80 | 0.80 (0.58–1.11) | .1801 |

| White race | −0.013 | 0.158 | 0.01 | 0.99 (0.73–1.35) | .9354 |

| Dual-eligible Medicaid/Medicare | 0.132 | 0.183 | 0.52 | 1.14 (0.80–1.64) | .4698 |

| CAD | −0.119 | 0.168 | 0.50 | 0.89 (0.64–1.23) | .4772 |

| CHF | −0.066 | 0.171 | 0.15 | 0.94 (0.67–1.31) | .7001 |

| Hypertension | −0.188 | 0.254 | 0.55 | 0.83 (0.50–1.36) | .4589 |

| Arthritis | 0.041 | 0.177 | 0.05 | 1.04 (0.74–1.47) | .8169 |

| Diabetes | −0.175 | 0.154 | 1.29 | 0.84 (0.62–1.14) | .2552 |

| COPD | 0.073 | 0.166 | 0.20 | 1.08 (0.78–1.47) | .6574 |

| Cancer | 0.208 | 0.170 | 1.50 | 1.23 (0.88–1.72) | .2204 |

| Liver disease | −0.214 | 0.214 | 0.99 | 0.81 (0.53–1.23) | .3187 |

| Stroke | −0.145 | 0.178 | 0.67 | 0.87 (0.61–1.23) | .4141 |

| Renal disease | −0.768 | 0.474 | 2.63 | 0.46 (0.18–1.17) | .1049 |

| Dementia | 0.541 | 0.220 | 6.02 | 1.72 (1.12–2.64) | .0141 |

| ADL impairments | −0.008 | 0.014 | 0.35 | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | .5535 |

| Cognitive performance scale | −0.041 | 0.219 | 0.03 | 0.96 (0.63–1.48) | .8524 |

| Dementia hospice diagnosis (vs cancer) | 0.633 | 0.273 | 5.37 | 1.88 (1.10–3.21) | .0205 |

| Failure to thrive hospice diagnosis (vs cancer) | 0.782 | 0.300 | 6.81 | 2.19 (1.22–3.93) | .0091 |

| Heart disease hospice diagnosis (vs cancer) | 0.370 | 0.327 | 1.29 | 1.45 (0.76–2.75) | .2568 |

| Lung disease hospice diagnosis (vs cancer) | 0.628 | 0.310 | 4.11 | 1.87 (1.02–3.44) | .0426 |

| Other primary diagnosis (vs cancer) | 0.442 | 0.252 | 3.09 | 1.56 (0.95–2.55) | .0787 |

| On hospice before nursing home admission | 1.609 | 0.225 | 51.33 | 5.00 (3.22–7.77) | <.0001 |

| Prior hospice stay | 1.338 | 0.600 | 4.98 | 3.81 (1.18–12.35) | .0257 |

| Hospital stay in prior year to hospice | −0.512 | 0.164 | 9.78 | 0.60 (0.44–0.83) | .0018 |

| Hospice admission year 1999–2000 (vs 2007–2008) | −0.682 | 0.391 | 3.04 | 0.51 (0.24–1.09) | .0812 |

| Hospice admission year 2001–2002 (vs 2007–2008) | −0.029 | 0.264 | 0.01 | 0.97 (0.58–1.63) | .9113 |

| Hospice admission year 2003–2004 (vs 2007–2008) | −0.202 | 0.204 | 0.98 | 0.82 (0.55–1.22) | .3224 |

| Hospice admission year 2005–2006 (vs 2007–2008) | –0.078 | 0.185 | 0.18 | 0.93 (0.64–1.33) | .6744 |

ADL, activities of daily living; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OR, odds ratio.

Patterns of Hospice Use

Upon examination of nursing home and hospice admission/enrollment and discharge/disenrollment dates, we identified a variety of different patterns as patients moved across settings while also enrolled in hospice. The most common pattern (79%, n = 1142) was patients living in a nursing home who enrolled in hospice and remained in the nursing home. A minority (16%, n = 183) of these patients disenrolled before death. Only 39 (3%) enrolled in hospice the day they were admitted to the nursing home. Other patients spent some time in the community and some time in a nursing home during a continuous hospice stay (21%, n = 310). More than half of these patients (11.5% of total nursing home hospice population, n = 167) enrolled in hospice in the community and then entered a nursing home, where they remained; 37 of these patients disenrolled before death. Enrolling in hospice while in a nursing home and then being discharged to the community on hospice was the pattern for 102 (7%). Less common were patients who enrolled on hospice in the community, spent time in a nursing home, and then were discharged to the community again (2.8%, n = 41; Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Common patterns of hospice use overlapping with nursing home residence.

Nearly 18% (n = 258) of the nursing home hospice patients disenrolled from hospice before death. Of all 258 patients who disenrolled before death, 16% died within the next 7 days, 27% died within 30 days, and 53% died by 1 year after disenrollment. Of those who disenrolled from hospice before death, about one third was hospitalized at some point in the year after disenrollment.

Discussion

Growing use of the Medicare hospice benefit has cast a spotlight on its role in nursing homes and raised questions about whether it is being used appropriately in this setting. National trends have shown that length of hospice stay has increased over time for nursing home patients, from a mean of 46 days in 1999 to 93 days in 2006, in parallel with increasing numbers of patients with noncancer diagnoses.19 Another study, focused on decedents in nursing homes who used hospice, also found an increase in noncancer diagnoses but a lower mean length of stay driven by increasing numbers of people who used the benefit for ≤7 days.23 In our lower income, urban Midwest cohort with higher numbers of nonwhite patients, noncancer diagnoses also increased over time. However, the hospice length of stay was consistently high throughout the 10-year study period, with a mean length of 114 days.

There are three key findings in this analysis that merit further discussion. First, although hospice eligibility is often ascribed to a single diagnosis (eg. heart failure), these data demonstrate significant comorbidity among older adults receiving the hospice benefit in the nursing home. Second, although these patients have a significant burden of cognitive and functional impairment, neither these impairments, as systematically measured by MDS assessment, nor age are significant predictors of hospice length of stay. Third, it is difficult to isolate nursing home hospice care as a specific targeted benefit from community-based hospice care because patients often receive hospice care in the community before or after the nursing home stay. In addition, many patients disenroll from hospice before death. These patterns have important implications for any policies designed to deter or promote hospice care in the nursing home.

In this analysis, we compared nursing home patients who received hospice for ≤180 or >180 days (ie. those who exceeded the anticipated 6-month life expectancy and remained on hospice). Nearly 20% of the population studied had a hospice length of stay longer than 6 months. Another recent study found that about 15% of patients had hospice stays longer than 6 months; their study focused on nursing home decedents, which may account for differing findings.23 The only factors significantly associated with long hospice stays were enrolling in hospice before nursing home admission and hospice primary diagnoses of failure to thrive, dementia, and lung disease. The clinical context for a given patient is more complicated than a single hospice diagnosis; 92% of all nursing home hospice patients had ≥3 comorbidities. The greater burden of cardiovascular disease in the ≤6-month group, regardless of primary hospice diagnosis, may explain why some patients did not live as long and thus had shorter hospice stays. We did not, however, find other systematic differences based on demographic and clinical characteristics, notably race or having advanced dementia (cognitive performance scale score = 5 or 6), between nursing home patients on hospice ≤6 or >6 months. Hospitalization in the year before enrollment in hospice was associated with a hospice stay of ≤6 months; patients requiring hospitalization may be sicker and more clinically unstable. Nursing home patients are medically complex and have functional impairments: Although these analyses identified some differences between those who were on hospice ≤6 or >6 months, clear patterns that could reliably predict length of stay did not emerge.

This study’s findings indicate that “nursing home hospice patients” are not a homogenous group. The varying patterns of use across treatment settings may have implications if access to the hospice benefit were to change in the nursing home setting. Residential nursing home patients who enroll in hospice at the end of life represent more than half of the patients in these analyses, but there are multiple other utilization patterns. About 12% of our nursing home hospice cohort represented community-dwelling patients who enrolled in hospice before admission to the nursing home, possibly because of increased care needs that could not be managed at home. In contrast, 7% were nursing home patients who enrolled in hospice and then transitioned into the community. These groups could be affected in different ways if the structure of the current hospice benefit were altered, that is, if a separate hospice benefit was developed for use in a nursing home setting. Any modifications to the existing hospice benefit need to take into consideration transitions between care settings and allow for such movement while maintaining hospice enrollment to accommodate patients’ needs.

Overall, nearly 18% of nursing home patients disenrolled from hospice and more than one third of those with hospice stays longer than 6 months disenrolled before death. About 15% of all Medicare hospice beneficiaries disenrolled before death in 2009.15 More than half of the patients in our cohort who disenrolled subsequently died within a year. The findings suggest that although many patients did not fit into the less than 6 months life expectancy of Medicare benefit, they were near the end of their lives, and thus a broader hospice benefit, or access to nonhospice palliative care, could be appropriate. There are many potential reasons for disenrollment from hospice. Hospice providers may choose to disenroll patients who no longer meet the prognostic eligibility criteria of a life expectancy of ≤6 months, and patients can choose to disenroll at any time (eg, if they decide they want curative interventions). Nonwhite patients have been found to be more likely to disenroll from hospice24,25; in this cohort, about 40% of the patients were nonwhite, which may help explain why our disenrollment rates were greater. Other analyses have found that disenrollment before death is more likely for patients with noncancer diagnoses, for whom prognosis may be less certain.26 It is likely that patients who survive longer than 6 months on hospice and then ultimately disenroll experience a more stable clinical course than anticipated. Increased access to nonhospice palliative care would decrease the burden of predicting life expectancy, which is challenging in this patient population, and place the emphasis on matching patient goals with treatments.

Our study has several limitations. First, our cohort was drawn from a safety net hospital that serves a population that is disproportionately poor, nonwhite, and characterized by high health care costs and a large population of older adults who are dual eligible. Although our results generalize to the growing population of older adults served by safety net providers, our findings may differ from the experiences of other nursing home patients in Indianapolis or nationally. With the data available in this retrospective analysis, we could not determine many important variables that influence patterns of hospice or nursing home use, including social support and preferences for care.

Despite the increasing use of hospice in the nursing home setting, most people who die in nursing homes are not receiving hospice. There are also concerns that the hospice benefit is underused in this setting,13 and unmet palliative care needs in nursing homes have been described.4–8 Hospice use has been associated with improvement in end-of-life care in nursing homes,9–12 and access to hospice should be preserved for these patients. Some have advocated for a new benefit to replace hospice in nursing homes, through which Medicare would pay nursing homes directly for providing palliative and restorative care.27 Although this strategy has the potential advantages of directly paying the nursing home and keeping the locus of accountability within the facility, as opposed to an outside hospice agency, there are limitations to this approach in the current environment, including disruption in care if patients move across settings. Targeting the appropriate population within the nursing home would continue to present challenges, as well as significant concerns about staff turnover and staff skill level and current training in palliative care.27

Conclusions

Access to palliative and end-of-life care in nursing homes is a critical issue for patients, families, providers, and policymakers. Policymakers seeking to reform the use of the hospice benefit in nursing homes should take into account the difficulty in predicting the clinical course of patients with serious, advanced illness, varying utilization patterns and transitions across settings that make it difficult to define a strictly “nursing home hospice” population, and the importance of supporting multiple approaches for delivery of palliative care in this setting.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Palliative Care Research Center Grant 4183655 and National Institute on Aging Grants R01 AG031222 and K24 AG024078.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR, Strahan CW. The National Nursing Home Survey: 2004 overview. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2009;13:1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. [Accessed August 2012]. Health, United States, 2010: With special feature on death and dying. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus10.pdf; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiener J, Freiman M, Brown D. Nursing home quality: Twenty years after the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2007. [Accessed August 1, 2012]. Available at: www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7717.pdf; [Google Scholar]

- 4.Improving palliative care in hursing homes. New York, NY: Center for Advance Palliative Care; 2008. [Accessed August 2012]. Center to Advance Palliative Care. Available at: www.capc.org/support-from-capc/capc_publications/nursing_home_report.pdf; [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen-Mansfield J, Lipson S. Pain in cognitively impaired nursing home residents: How well are physicians diagnosing it? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1039–1044. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanson LC, Eckert JK, Dobbs D, et al. Symptom experience of dying long-term care residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller SC, Mor V, Teno J. Hospice enrollment and pain assessment and management in nursing homes. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26:791–799. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1529–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baer WM, Hanson LC. Families’ perception of the added value of hospice in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:879–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gozalo PL, Miller SC. Hospice enrollment and evaluation of its causal effect on hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:587–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller SC, Mor V, Wu N, et al. Does receipt of hospice care in nursing homes improve the management of pain at the end of life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:507–515. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munn JC, Dobbs D, Meier A, et al. The end-of-life experience in long-term care: Five themes identified from focus groups with residents, family members, and staff. Gerontologist. 2008;48:485–494. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Lee IC. Does hospice improve quality of care for persons dying from dementia? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1531–1536. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medpac. Hospice services: Assessing payment adequacy and updating payments. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. [Accessed August 2012];Medpac. 2012 Available at: medpac.gov/chapters/Mar12_Ch11.pdf.

- 15.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO facts and figures: Hospice care in America. [Accessed August 2012];NHPCO. 2011 Available at: www.nhpco.org/files/public/Statistics_Research/2011_Facts_Figures.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Hernandez AF, et al. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among medicare beneficiaries with heart failure, 2000–2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:196–203. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindrooth RC, Weisbrod BA. Do religious nonprofit and for-profit organizations respond differently to financial incentives? The hospice industry. J Health Econ. 2007;26:342–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Office of Inspector General. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Accessed August 2012]. Medicare hospices that focus on nursing facility residents. Available at: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-10-00070.pdf; [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller SC, Lima J, Gozalo PL, et al. The growth of hospice care in US. nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1481–1488. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callahan CM, Ailing G, Tu W, et al. Transitions in care for older adults with and without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:813–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callahan CM, Weiner M, Counsell SR. Defining the domain of geriatric medicine in an urban public health system affiliated with an academic medical center. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1802–1806. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. New York, NY: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterns S, Miller SC. Medicare hospice care in US nursing homes: A 2006 update. Palliat Med. 2011;25:337–344. doi: 10.1177/0269216310389349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA. What explains racial differences in the use of advance directives and attitudes toward hospice care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1953–1958. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01919.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Johnson KS, et al. Racial differences in hospice use and patterns of care after enrollment in hospice among Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2012;163:987–993. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.03.006. e983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kutner JS, Meyer SA, Beaty BL, et al. Outcomes and characteristics of patients discharged alive from hospice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1337–1342. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huskamp HA, Stevenson DG, Chernew ME, et al. A new medicare end-of-life benefit for nursing home residents. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:130–135. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]