Abstract

[Purpose] The purpose of this study were to identify whether painless dynamic PNF techniques can reduce lymphedema, and to provide basic reference data for use in the treatment of lymphedema patients. [Subjects] This experiment was conducted from March 2012 to July 2012 at Busan University Hospital D. The subjects were upper extremity lymphedema patients who were receiving rehabilitation treatment. Those with dual lymphedema site pain or who did not want to participate in the experiment were excluded. [Methods] A total of 40 women participated in this study, and they received PNF techniques before the application of lymph compression bandages. Group 1 of 20 subjects were adminstered PNF techniques three times a week for 30 minutes each time. Group 2 of 20 subjects only edema reducing massage for 30 minutes. [Results] The interaction between treatment method and treatment time was significant, which indicates that the change in edema at different measurement times was different according to treatment methods. In this study, Group 1 had a steeper rate of decline in edema than Group 2. [Conclusion] In conclusion, both massage and PNF techniques helped to lower edema rates. Four weeks after the beginning of treatment, a larger degree of decline in edema was exhibited in the PNF group than in the massage group.

Key words: PNF techniques, Lymphedema, Lymph massage

INTRODUCTION

A recent increase in cancer operations has led to more patients with damaged lymphoid organs. Damaged lymphoid organs disturb activities maintaining lymph balance, by absorbing unnecessary properties in lymphoid tissues, subsequently caus edema in the arms or legs. This symptom is called lymphedema. Lymphedema is the accumulation of protein-rich fluids in the interstitium due to the lack of transport ability in the lymphatic system, and usually develops in one or more areas1, 2). Primary lymphedema is caused by congenital anaplasia, hypoplasia, and hyperplasia in the lymphatic system, and secondary lymphedema is caused by damage to the lymphatic system through infection, inflammation, surgery/cancer/trauma, or radiation treatment3, 4). Once lymphedema occurs, it results in pain, a sense of heaviness, reduced movements, related deformation of joints and muscles, skin contraction, loss of libido, changes in social perception, repetitive infection, and subsequent psychological conflicts and disorders5). Additionally, although rare, it can even cause death from complications due to the lethal onset of secondary lymphangiosarcoma.

The purpose of the treatment for lymphedema is not to cure it completely but to reduce the size of the edema. Medication is insufficiently effective enough and surgery has its limits. Currently, Complete Decongestive Therapy (CDT) defined by Dr. Foldi in 1989, which includes manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), skin care, therapeutic excercise, and compression stockings, is known as the most effective non-surgical technique in the treatment of lymphedema6, 7). A lasting condition of edema and chronic inflammation from the abnormal accumulation of tissue protein due to lymphedema is loss of muscle flexibility, and as a result, limitations in making movements8,9,10). Therefore, proper exercise plays a role in maintaining the optimal range of motion (ROM)10). PNF stretching involves moving within a range without causing pain8, 9, 11), and has become an important element in reducing and preventing exercise injuries through enhanced flexibility and the increase in blood flow9, 11, 12). Moreover, PNF stretching heightens the accuracy of exercise and muscle activity, in addition to improving body coordination8, 12, 13). Therefore, for lymphedema patients, the improvement of their motor competency and ROM in the body parts that develop limited exercise performances may be urgently required.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The subjects of this study were the patients who were diagnosed with lymphedema in the upper limbs and received rehabilitation treatment at D University Hospital in Busan from March to July, 2012. Among the candidates, those who had pain in the area of lymphedema or did not want to participate in our experiment were excluded. The physical characteristics of the subjects are as shown in Table 1. A total of 40 women participated in this study. for Group 1 of 20 subjects performed PNF stretching three times a week for 30 minutes each time. Before the main stretching, they performed wrist turning, basic massage, and joint exercise for about five minutes. Then, they used the PNF techniques of rhythmic initiation (RI), and a combination of isotonic (CI), contract-relax, and hold-relax. Group 2 of 20 subjects only practiced edema reducing massage for 30 minutes. This experiment consisted of a test group that performed PNF stretching and a control group that performed general massage.

Table 1. General characteristics of the subjects.

| Group | ||

| Stretching (n=20) | Massage (n=20) | |

| Age (yrs) | 50.2±4.4 | 53.5±3.6 |

| Height (cm) | 162.0±2.6 | 161.3±3.5 |

| Weight (kg) | 59.7±4.1 | 61.3±3.2 |

In order to measure edema, the same measurer conducted a blind test before and after each treatment. The girths of each upper limb of the proximal and distal parts that are 10 cm from the olecranon were measured. We calculated the decline in the girth of edema by the equation shown below, and used the opposite side with no edema as the base of comparison.

| < Edema rate (% excess) = ((the affected side − the unaffected side) / the unaffected side) × 100% > |

Descriptive statistical analysis was carried out of the general characteristics of the research subjects, such as age, height, and weight, using mean±SEM (standard error of measurement). In order to examine the difference in edema rates according to treatment method and time, the mean±SEM of edema rates according to each treatment time in each treatment method was calculated. Additionally, in order to statistically verify the results, repeated measures ANOVA was employed. Here, to test the differences between each treatment method and time, the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was conducted. The statistical significance level used in hypothesis testing was 0.05 and all statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS Version 18.

RESULTS

The mean±SE (standard error) of age of the subjects was 50.2±4.4 years in the group that performed PNF stretching, and 53.5±3.6 in the group that performed massage, and a statistically significant difference existed in age between the two groups. For height and weight, however, no statistically significant differences were observed (p>0.05).

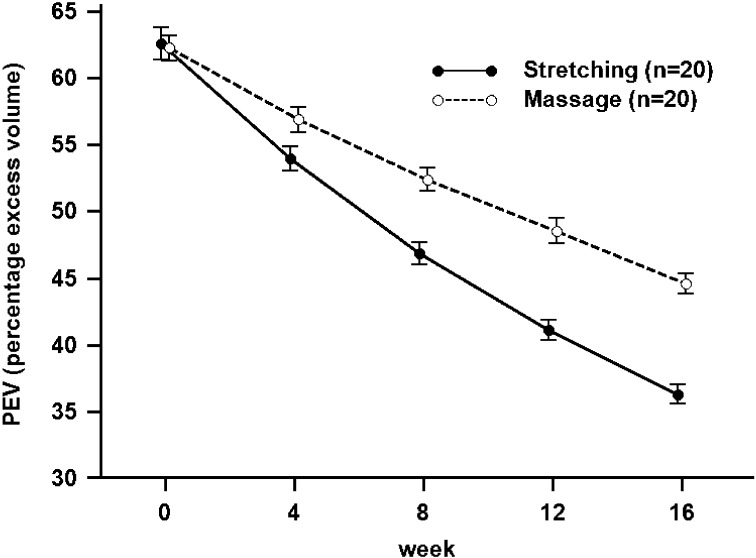

The results of the statistical significance testing using repeated measures ANOVA are shown in Table 2. The differences of edema rates according to treatment method were statistically significant (F=63.49, p<0.05), and as shown in Fig. 1, the PNF stretching group generated a statistically more significant reduction than the massage group. Additionally, the effects of the pre-treatment edema rates on the post-treatment edema rates were statistically significant (F=36.28, p<0.05). The differences of edema rates according to measurement time were also statistically significant (F=427.74, p<0.05), and as illustrated in Fig. 1, a pattern of reduction in edema rates with the passage of time was exhibited. Furthermore, the interaction between treatment method and treatment time was statistically significant (F=14.61, p<0.05).

Table 2. Results of the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc tests of the mean difference between the two groups at the different test times.

| Moment | Group (I) | Group (J) | Mean difference (I–J) | 95% CI |

| 4 weeks | stretching | massage | 3.11 | (0.18–6.04) |

| 8 weeks | stretching | massage | 5.71* | (2.78–8.64) |

| 12 weeks | stretching | massage | 7.62* | (4.69–10.55) |

| 16 weeks | stretching | massage | 8.47* | (5.54–11.40) |

*: p<0.05

Fig. 1.

Mean ± SEM plot of percentage excess volume of the two treatment groups

The difference of edema rates between the PNF stretching group and the massage group four weeks after the beginning of treatment was 3.11% and the 95% confidence interval was estimated as. Therefore, the edema rates between the PNF stretching and massage groups four weeks after the beginning of treatment was significantly different. As time progressed the difference in the edema rates between the groups became wider, and the difference in the edema rates between the two groups at every test time was revealed to be statistically significant (p<0.05).

In addition, the interaction between treatment method and treatment time was significant (p<0.05), indicating that the changes in the edema rates at different measurement times were different according to treatment method. In this study, the PNF stretching group showed a steeper decline in the edema rate than the massage group.

In other words, if there had been pre-treatment homogeneity in edema rates between the PNF stretching and massage groups, the PNF stretching and massage treatment methods would have shown a statistically significant decline of edema rates between the two groups at every test time after the beginning of treatment. PNF stretching was also revealed to generate a greater degree of decline in edema the massage group than, which also showed a statistically significant decline.

DISCUSSION

In this study, massage and PNF stretching treatments were conducted for 40 women with lymphedema who were in their 50s or older over a period of 16 weeks. Compared to the result of the pre-treatment test, declines in edema rates were observed at 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks after the beginning of treatment the subjects' lymphedema areas.

Lymphedema is caused by treatments that damage the lymph glands, e.g. mastectomy. Particularly, lymphedema patients experience various symptoms such as a sense of heaviness, swelling, sinking in when pressed, hotness, pricking with a needle, and tearing. As edema progresses, the patients experience weakened function of the shoulder joints, pain, and an increased sense of fatigue. The chances of developing lymphedema are reported to be 2–27% after surgery for breast cancer and 9–36% after radiation treatment. Most of the subjects in this study expressed high interest in active prevention methods and treatments to ward off the symptoms of edema after surgery or treatment. Conventional treatment methods remain inadequate, while exercise therapies using massage and PNF stretching have been proven to be the most effective methods. This study verified that the difference in the declines of edema rates between the massage and PNF stretching treatment methods was statistically significant. Specifically, PNF stretching was revealed to generate a greater degree of decline in the edema rate than massage. Overall, in treating lymphedema, massage and stretching were both proven to be effective. Thus, therapists will need to select a suitable method after examining the muscle strength and flexibility of each individual patient.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Kyungsung University Research Grant in 2013.

REFERENCES

- 1.Földi E, Földi M, Clodius L: The lymphedema chaos: a lancet. Ann Plast Surg, 1989, 22: 505–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mortimer PS, Bates DO, Brassington HD, et al. : The prevalence of arm oedema following treatment for breast cancer. Q J Med, 1996, 89: 377–380 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan MJ, Depompolo RW, Garden FH: Focused review: postmastectomy lymphedema. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 1996, 77: S74–S80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smeltzer DM, Stickler GB, Schirger A: Primary lymphedema in children and adolescents: a follow-up study and review. Pediatrics, 1985, 76: 206–218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirshbaum M: Using massage in the relief of lymphoedema. Prof Nurse, 1996, 11: 230–232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lymphology Executive Committee: The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema. Consensus document of the International society of Lymphology Executive Committee. Lymphology, 1995, 28: 113–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mortimer PS: Therapy approaches for lymphedema. Angiology, 1997, 48: 87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim YB: Effects of static stretching and muscle energy technique stretching on the extensibility of back extensors in healthy subjects. Korea Sport Res, 2006, 17: 401–410 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prentice WE: Rehabilitation Techniques in Sports Medicine 3rd ed. McGraw-hill, 1999, pp 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- 10.ACSM: ACSM's Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006, pp 350–365. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prentice WE, Voight MI: Techniques in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. McGrawHill, 2001, pp 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feland JB, Marin HN: Effect of submaximal contraction intensity in contract-relax proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching. Br J Sports Med, 2004, 38: E18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kisner C, Colby LA: Therapeutic Exercise 5th ed. 2007, pp 65–104.