Abstract

The epidemiological transition, with a rapid increase in the proportion in the global population aged over 65 years from 11% in 2010 to 22% in 2050 and 32% in 2100, represents a challenge for public health. More and more old persons have multimorbidities and are treated with a large number of medicines. In advanced age, the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of many drugs are altered. In addition, pharmacotherapy may be complicated by difficulties with obtaining drugs or adherence and persistence with drug regimens. Safe and effective pharmacotherapy remains one of the greatest challenges in geriatric medicine. In this paper, the main principles of geriatric pharmacology are presented.

1. Introduction

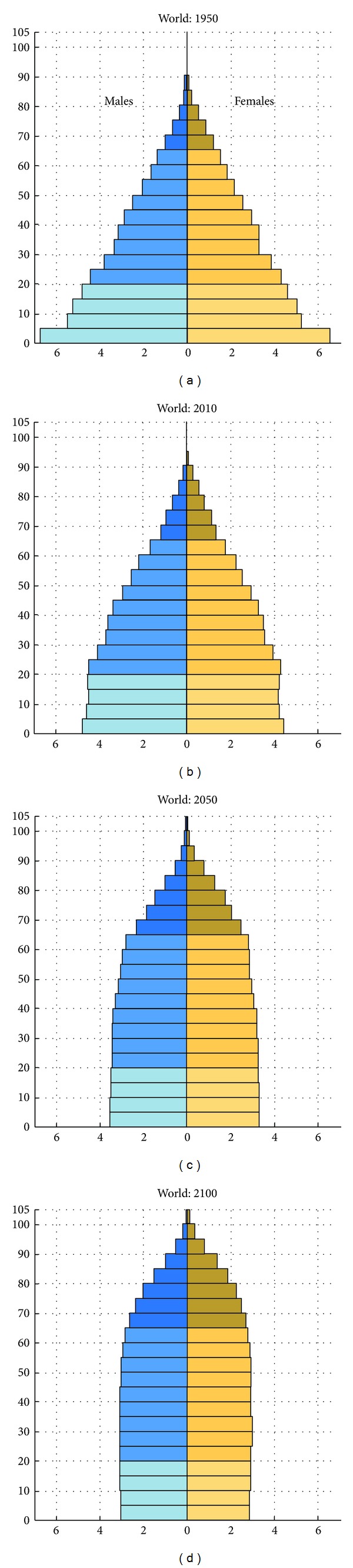

The worldwide population, within the age group 65 years and older has increased rapidly in the last century and a further increase is expected (Figure 1). The proportion of the global population over 65 years old increases from 11% in 2010 to 22% in 2050 and 32% in 2100 [1, 2]. The proportion aged above 80 years in western Europe will increase from 4% in 2010 up to 10% in 2050.

Figure 1.

Increase in life expectancy from 1950 until 2100. Population by age groups and sex expressed as percentage of total population [2].

The ageing of the world's population is the result of several factors: installation of sewers and improvement of potable water, improvement of quality of food and preservation of food, better housing, education, more attention for physical condition, and developments in medical sciences [3]. Prevention and treatment of infectious and cardiovascular diseases and development of anaesthesiology medicines and technics have, amongst others, contributed considerably to the increase in life expectancy. An epidemiological transition in the leading causes of death, from infectious disease and acute illness to noncommunicable chronic diseases and degenerative illnesses is happening. Developed countries in North America, Europe, and the Western Pacific already underwent this transition, and other countries are at different stages of progression. The epidemiological transition, combined with the increasing number of older people, represents a challenge for public health. More and more old persons have multimorbidities and are treated with five medicines or more. In advanced age, the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of many drugs are altered. In addition, pharmacotherapy may be complicated by difficulties with obtaining drugs or complying with drug regimens. Safe and effective pharmacotherapy remains one of the greatest challenges in geriatric medicine. In this paper, the principles of geriatric pharmacology are presented.

2. Age-Related Changes in Pharmacokinetics

With increasing age and because of change in body weight, several changes in pharmacokinetics are present in many elderly people. Especially changes in volume of distribution and renal clearance are of clinical importance [4].

2.1. Drug Absorption

Pharmacokinetic studies on the effect of ageing on drug absorption have provided conflicting results. Several studies have not shown age-related differences in absorption rates for different drugs [5]. However, other studies have shown an increased absorption of, for example, levodopa. For drugs absorbed by passive diffusion there is low grade evidence for age-related changes. In general no adaptation of the dose is needed because of the ageing process.

2.2. First-Pass Metabolism and Bioavailability

There is a reduction in first-pass metabolism with advancing age. This is probably due to a reduction in liver mass and, for high clearance drugs, the consequential reduction in blood flow. The bioavailability of drugs which undergo extensive first-pass metabolism such as opioids and metoclopramide, can be significantly increased. For these drugs a low start dose is advised. By contrast, the first-pass activation of several prodrugs, such as the angiotensin-converting-enzyme-(ACE-) inhibitors enalapril and perindopril, might be slower or reduced [6]. However, this is not clinically relevant due to the chronic usage.

2.3. Drug Distribution in the Body

Significant changes in body composition occur with advancing age, such as a progressive reduction in the proportion of total body water and lean body mass. This results in a relative increase in body fat. Hydrophilic drugs tend to have smaller volume of distribution (V) resulting in higher serum levels in older people (e.g., gentamicin, digoxin, lithium, and theophylline). The consequence may be that the loading dose should be lower than in young adults. The reduction in v for water-soluble drugs tends to be balanced by a larger reduction in renal clearance (CL), with a smaller effect on elimination half life (t 1/2el). By contrast, lipophilic drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines, morphine, and amiodarone) have a lower water solubility so their V increases with age. The main effect of the increased V is a prolongation of half-life. Increased V and t 1/2el have been observed for drugs such as diazepam, thiopental and lidocaine. The consequence is that old patients may have long-lasting effects and adverse effects after cessation of the therapy [4].

2.4. Protein Binding

Acidic compounds (e.g., diazepam, phenytoin, warfarin, acetylsalicylic acid) bind mainly to albumin whereas basic drugs (e.g., lidocaine, propranolol) bind to alpha-1 acid glycoprotein. Although no substantial age-related changes in the concentrations of both these proteins have been observed, albumin is commonly reduced in persons with malnutrition, cachexia, or acute illness whereas alpha-1 acid glycoprotein is increased during acute illness. The main factor which determines the drug effect is the free (unbound) concentration of the drug. Although plasma protein binding changes might theoretically contribute to drug interactions or physiological effects for drugs that are highly protein-bound, its clinical relevance is limited for most of the drugs [13]. However, for some medicines, for example, phenytoin, drug effects may be enhanced and more ADR could be seen with low albumin concentrations [14].

2.5. Drug Clearance

2.5.1. Liver

Drug clearance by the liver depends on the capacity of the liver to metabolize the drug from the blood passing through the organ (hepatic extraction ratio) and hepatic blood flow. Drugs can be classified into three groups according to their extraction ratio (E): high (E > 0.7, such as dextropropoxyphene, lidocaine, pethidine, and propranolol), intermediate (E 0.3–0.7, such as acetylsalicylic acid, codeine, morphine, and triazolam), and low extraction ratio (E < 0.3, such as carbamazepine, diazepam, phenytoin, theophylline, and warfarin). When E is high, the clearance is rate-limited by blood flow. When E is low, changes in blood flow produce little changes in clearance. Therefore, the reduction in liver blood flow with ageing mainly affects the clearance of drugs with a high extraction ratio. Of much greater importance is the reduction in liver volume up to as much as 30% across the adult age range.This results in a reduction in clearance of a similar magnitude [15]. Several studies have shown significant age-related reductions in the clearance of many drugs metabolised by phase-1 pathways in the liver. These involve reactions such as oxidation and reduction. The amount of total Cytochrome P 450-metabolizing enzymes (CYP) is decreased in patients over 70 years of age with about 30% [16]. By contrast, phase-2 pathways (e.g., glucuronidation) do not seem to be significantly affected [15]. However, in general the reduction in hepatic clearance is not of clinical relevance and dose reduction is not needed.

2.5.2. Kidney

The age-related reduction in glomerular filtration rate affects the clearance of many drugs such as water-soluble antibiotics, diuretics, digoxin, water-soluble beta-blockers, lithium, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and newer anticoagulant drugs like dabigatran and rivaroxaban. The clinical importance of such reductions of renal excretion is dependent on the likely toxicity of the drug. Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index like aminoglycoside antibiotics, digoxin, and lithium are likely to have serious adverse effects if they accumulate only marginally more than intended. In elderly patients the serum creatinine may be within the reference limits, while renal function is markedly diminished. Estimation of the creatinine clearance or glomerular filtration rate with the Cockcroft and Gault or the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equations may be helpful. However these methods are not yet validated in frail elderly patients, therefore one should be careful when using these equations [17–19].

3. Age-Related Changes in Pharmacodynamics

Studies of drug sensitivity require measurement of concentrations of drug in plasma, as well as measurement of drug effects. Pharmacodynamics are determined by concentrations of the drug at the receptor, drug receptor interactions (variations in receptor number, receptor affinity, second messenger response, and cellular response), and homeostatic regulation. Few data are available on pharmacodynamic differences in very old persons [20]. Some important pharmacodynamic age-related changes are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected pharmacodynamic changes with ageing.

| Drug | Pharmacodynamic effect | Age-related change |

|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics | Sedation, extrapyramidal symptoms | Increased |

| Benzodiazepines | Sedation, postural sway | Increased |

| Beta-agonists | Bronchodilatation | Decreased |

| Beta-blocking agents | Antihypertensive effects | Decreased |

| Vitamine K antagonists | Anticoagulant effects | Increased |

| Furosemide | Peak diuretic response | Decreased |

| Morphine | Analgesic effects, sedation | Increased |

| Propofol | Anesthetic effect | Increased |

| Verapamil | Antihypertensive effect | Increased |

3.1. Anticoagulants

A number of studies have shown that the frequency of bleeding events associated with anticoagulants therapy and response to warfarin increase with age [20, 21]. There is evidence of a greater inhibition of synthesis of activated vitamin K-dependent clotting factors at similar plasma concentrations of warfarin in elderly compared to young patients. If vitamin K-antagonists (VKAs) are monitored carefully, age in itself is not a contraindication for treatment and as presented in an Italian study in the very old, the VKA's have acceptable low rates of bleeding incidents [22]. Concerning the new anticoagulants, dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban, prescribers should be aware of the differences between well-controlled trials and daily practice, especially concerning adverse drug events (ADEs). If prescribed to the elderly, appropriate doses should be used [23].

3.2. Cardiovascular Drugs

3.2.1. Calcium Channel Blockers

Although elderly subjects are less sensitive to the effects of verapamil on cardiac conduction, older people do show a greater drop in blood pressure and heart rate in response to a given dose of verapamil [20]. This might be explained by an increased sensitivity to the negative inotropic and vasodilatating effects of verapamil, as well as diminished baroreceptor sensitivity. Diltiazem also shows age-related changes in metabolism, but these changes do not appear to affect blood pressure or heart rate response [24]. The administration of diltiazem as a bolus injection causes greater prolongation of the PR interval (dromotropic effect) in young than in elderly subjects [4].

Dihydropyridines initially have a greater effect on blood pressure in elderly persons, possibly due to an age-related decrease in baroreceptor response. The greater effect may be transient and disappears in about 3 months [20].

3.2.2. Beta-Blocking Agents

Reduced β-adrenoreceptor function is observed in advanced age. Both β-agonist and β-antagonist show reduced responses with age [20]. This is secondary to impaired β-receptor function due to variations in receptor confirmation, alterations in binding affinity to the guanine nucleotide subunit (G s), or receptor downregulation. The total number of receptors seems to be maintained but the postreceptor events are changed because of alterations of the intracellular environment. The responsiveness of α-adrenoreceptors is preserved with advancing age.

3.3. Central Nervous System-Active Drugs

Many drugs affecting the central nervous system (CNS) cause an exaggerated response in older persons. Elderly patients are particularly vulnerable to adverse effects of antipsychotics, such as extrapyramidal motor disturbances, arrhythmias, and postural hypotension. Agents with anticholinergic effects can also impair cognition and orientation in patients with a cholinergic deficit such as those with Alzheimer's disease. Advanced age is also associated with increased sensitivity to the central nervous system effects of benzodiazepines. Postural sway is increased and patients are more likely to lose their balance after triazolam administration [25]. The sedative effects of midazolam are much stronger with the regular given dose [26]. The exact mechanisms responsible for the increased sensitivity to these drugs with ageing are unknown. However, drugs may penetrate the CNS more readily with advancing age. For example, functional activity of the P-glycoprotein efflux pump in the blood-brain barrier is reduced by aging [27]. Reported differences for the benzodiazepines could be due to differences in drug distribution to the CNS.

Anaesthetic agents generally show an increase in sensitivity in the elderly. For example, propofol sensitivity increases with age [28]. Neuromuscular blockers do not show increased sensitivity, lower dosing requirements are primarily due to altered pharmacokinetics [28]. Sensitivity of opioids increases by about 50% in elderly individuals [29, 30].

4. Variability in Response to Medicines

Older people display considerable variability in responses to medicines, as well as beneficial effects as adverse effects [31]. Patients may benefit from antipsychotics for delirium and behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia. Many other antipsychotics do not show benefit, but do have adverse effects [32]. About half of the patients treated with haloperidol suffer extrapyramidal motor disturbances, independent from daily dosage or serum haloperidol concentration [33]. A change in pharmacogenetic factors was not present. Another example is the variable response on anticoagulants. VKAs are associated with a significant risk of adverse outcomes leading to hospitalization in older people. Age, weight, and genotype of pharmacokinetic (CYP2C9) and pharmacodynamic (VKORC1) determinants account for about 60% of the variability in warfarin dose requirements [33–35]. The variability in drug response is multifactorial and the consequence of changes in organ-function, body composition, postreceptor response, homeostatic reserve, and comorbid disease [36, 37]. Also, pharmacogenetic factors may play a role. Frailty is increasingly recognized as a phenotype that is predicitve of adverse health outcomes in older people [38]. Inflammation associated with frailty has the potential to significantly alter drug transporter and metabolizing enzyme expression contributing to variability in drug clearance [39]. Changes in gene expression involve a very small fraction of genes [40]. All in all, the variabilities in responses to medicines are unlikely to have a strong pharmacogenic component [31].

5. Medication Use in Elderly Patients

Elderly patients often suffer from several chronic disorders and consequently use more drugs than any other age group. The diminished physiological reserve associated with ageing can be further depleted by acute or chronic disease states and effects of drugs. In most developed countries, about 2/3 of the population ≥65 years take prescription and over the counter (OTC) drugs. At any given time, an average elderly person uses 4-5 prescription drugs and two OTC drugs and fills 12–17 prescriptions a year [4]. The frail elderly patient uses often more than five different drugs. The nursing home resident in The Netherlands receives at least 7-8 different drugs. The mean number of drugs used at admission to a geriatric department was found to be ten [8]. On top of these patients used at mean two OTC medicines. The type of drug used varies with the setting. Nursing home residents use antipsychotics and sedative-hypnotics most commonly, followed by diuretics, antihypertensives drugs analgesics, cardiac drugs, and antibiotics. Psychoactive drugs are prescribed for ~65% of nursing home patients and for ~55% of residential care patients; ~7% of patients in nursing homes receive ≥3 psychoactive drugs concurrently. Community patients use analgesics, diuretics, cardiovascular drugs, and sedatives most often. Older people use OTC medicines to treat minor complaints such as pain, constipation, colds and gastrointestinal symptoms [41]. The most commonly used OTCs are, paracetamol, NSAIDs, antihistamines and drugs for gastric complaints like H2 receptor antagonists and protonpump inhibitors. In several countries statins and proton-pump inhibitors are also available as OTC drugs. There are concerns regarding the safety of OTC medicines, especially in elderly patients. In particular, sedatives may increase the risk of falls. The use of multiple medications increases the risk of drug-drug interactions and adverse effects. The varying degrees of hepatic and renal impairment and the potential for a larger pharmacodynamic effect of sedatives in old people can make OTC medicines, even with low doses, harmful. Cebollero-Santamaria et al. [42] showed that bleeding from a peptic ulcer was associated with use of NSAIDs in 81% of 84 patients and that 95% had purchased their NSAIDs as a OTC drug. The use of recommended doses of the OTC NSAIDs has a relatively good safety profile compared to prescription NSAIDs. However patients may take higher doses for a longer period without a gastroprotective drug with serious gastrointestinal toxicity as result [43]. Many older people use OTC drugs to improve their sleep. The risks associated with this use have not been examined [41]. Older people are not always aware of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) caused by OTC H2 receptor antagonists, such as confusion, and OTC statins, such as liver and skeletal muscle toxicity.

Documentation of OTC medicines in medical records is uncommon. Only 5% of OTC drugs, used by patients prior to and during hospitalization, were recorded on drug charts [44]. Asking elderly patients, especially those admitted to hospitals, for their use of OTC drugs is important to prevent double-prescription and clinically relevant drug-drug interactions. Not only NSAIDs and antihistamines may cause these interactions, but also herbal drugs as St. John's wort. St. John's wort is used to treat depressive symptoms. In Table 2 clinical important interactions of St. John's wort are summarized [7]. The increasing availability of OTC drugs clearly has benefits. Nevertheless, prescribers must always pay close attention to concomitant OTC medication use in order to minimize adverse drug reactions.

Table 2.

Clinically relevant drug interactions with St. John's wort [7].

| Drug | Effect of interaction with St. John's wort |

|---|---|

| Amitriptyline | Steady-state concentration decreased by 22% |

| Cyclosporine | Steady-state concentration decreased by 52% |

| Digoxin | Steady-state concentration decreased by 25% |

| Simvastatin | AUC decreased by 50% |

| Tacrolimus | Steady-state concentration decreased by 80% |

| Theophylline | Steady-state concentration decreased by 50% |

| VKAs | INR 50% lower |

AUC: area under plasma concentration time curve.

6. Polypharmacy versus Appropriate Prescribing

Many drugs benefit elderly patients. Some can be life-saving (i.e., antibiotics and thrombolytic therapy). Oral hypoglycemic agents can improve independence and quality of life while controlling chronic disease. Antihypertensive drugs and influenza vaccines can help prevent or decrease morbidity. Analgesics and antidepressants can control debilitating symptoms. Therefore, appropriateness, that is whether the potential benefits outweigh the potential risks, should guide therapy. Polypharmacy is often defined as the concurrent use of five or more different drugs. The main reasons for polypharmacy are longer life expectancy, multimorbidity and the implementation of evidence-based guidelines [45]. However, polypharmacy also has important negative consequences. Inappropriate polypharmacy contributes to unwanted and often preventable clinically relevant drug-drug and drug-disease interactions as well as adverse drug reactions (ADRs). One-year incidence of potentially inappropriate medication use of frail elderly was found to be 42,1% [46]. Approximately 12% of elderly patients in hospitals are admitted because of ADRs [47]. It is estimated that over half of these ADRs are preventable [21, 48, 49]. Multiple drug use in itself is not necessarily undesirable. The term appropriate prescribing addresses the problems of both inappropriate use of medication as well as inappropriate nonuse of medication (or undertreatment). Comprehensive geriatric assessment and medication review are effective methods to optimize polypharmacy and should comprise both inappropriate use as well as undertreatment [12, 45]. It has been proven that pharmacists and geriatricians may play an important role to optimize polypharmacy in elderly [50, 51].

7. Medication Review

Medication review is an essential process in the management of patients with chronic disease. The medication reconciliation process aims to reduce medications errors and consists of four steps [52]. The first step is verification, that is, the list of medications currently used is assembled. The second step is clarification and evaluation: each medication (including formulation and dosage) is checked for appropriateness. The third step is reconciliation: comparison of newly prescribed medications to the old ones and the documentation of the changes. The final step is transmission, in which the updated list is communicated to the next care provider. Medication reconciliation reduced by 43% of the patients adverse drug events (ADEs), which were caused by admission prescribing changes classified as errors, but did not reduce ADEs caused by all admission prescribing changes [53].

Several methods have been developed to assess the appropriateness of drugs prescribed to elderly patients, and methods can be divided into implicit and explicit methods [54, 55]. In an implicit method, medical knowledge and information from the patient are used to determine if a therapy is appropriate. Examples of validated, implicit screening tools are the Medication Appropriateness Index and the prescription optimization method [12, 56]. These methods are patient-tailored and provide opportunity to conduct a complete and flexible assessment of individual pharmacotherapy. Since implicit methods depend on patient information, they are capable of detecting nonspecified problems. However, these methods are often time consuming and are dependent on clinical judgment and knowledge of geriatric pharmacotherapy factors that may vary between physicians. This possible lack of knowledge is less relevant with explicit methods. These are more rigid screening tools based on literature review or expert consensus, and specify inappropriate drug combinations or contraindications. Inappropriate medications can be detected in a consistent manner. The structure of these tools makes it possible to incorporate them easily into software packages, and they can be used as so-called “clinical rules.” The most well-known explicit screening tool is the recently updated Beers drug list, which lists medications to be avoided or adjusted in elderly populations in general or in cases of specific morbidity [57]. Similar lists based on the Beers list have been developed in France, Canada and Norway [58–60]. Other examples of explicit screening tools are START (screening tool to alert doctors to the Right Treatment) and STOPP (screening tool of older person's prescriptions), which are system- defined medicine review tools [61–63]. Explicit screening tools have some disadvantages. For example, the inflexible approach can lead to false-positive signals, because individual patient characteristics or preferences are not taken into consideration—a drug may be inappropriate in general but appropriate for a specific patient. Also, false-negative signals may occur, because nonspecified problems are not detected by these methods. Factors such as time until benefit and drug monitoring are not taken into account. Underprescribing, which means that a disease is not treated according to guidelines, cannot usually be detected by these explicit screening tools (except the START screening tool, which is designed to detect underprescribing [61]).

The prescription optimization method (POM) covers all aspects for appropriate prescribing and consists of six questions [12].

Which drugs are really used by the patient? What is the degree of patients adherence?

Which drugs, that the patient uses, cause adverse effects?

Which drugs are necessary for the patient? Does undertreatment exists?

Which drugs are not necessary or contra-indicated?

Are there clinically relevant interactions?

Is the dose and the dose frequency appropriate?

7.1. Structured History to Improve Medication Taking in Elderly

The first step of medication reconciliation is to look at the medicines the patient really uses, including the OTC drugs [64]. Usually, the medication list is assembled by an unstructured interview with the patient. Various resources can be used, such as letters by referring physicians, medication vials, or community pharmacy listings. None of these sources has by itself proven to be completely accurate [65]. To provide physicians with a method for medication history taking, recently the structured history taking of medication use (SHIM, Table 3) was developed. SHIM revealed discrepancies in the medication histories of almost all patients. Actual clinical consequences occurred in one out of five patients, and almost half of these consequences are caused by discrepancies concerning nonprescription OTC drugs. SHIM has the potential to prevent these problems and therefore is a successful first step in the medication reconciliation process [8]. Important to note is that taste disturbances can affect adherence in itself as part of the ageing proces, or by taste disturbances induced by drugs [66, 67].

Table 3.

Structured history taking of medication use (SHIM) questionnaire (Drenth-van Maanen et al., 2011 [8]; http://www.ephor.eu).

| Questions asked per drug on the medication list, provided by the community pharmacist |

|---|

| (1) Are you using this drug as prescribed (dosage, dose frequency, dosage form)? |

| (2) Are you experiencing any side effects? |

| (3) What is the reason for deviating (from the dosage, dose frequency, or dosage form) or not taking a drug at all? |

| (4) Are you using any other prescription drugs, which are not mentioned on this list? (View medication containers) |

| (5) Are you using non-prescription drugs? |

| (6) Are you using homeopathic drugs or herbal medicines (especially st. Johns wort)? |

| (7) Are you using drugs that belong to family members or friends? |

| (8) Are you using any drugs “on demand”? |

| (9) Are you using drugs that are no longer prescribed? |

|

|

| Questions concerning the use of medicines |

|

|

| (10) Are you taking your medication independently? |

| (11) Are you using a dosage system? |

| (12) Are you experiencing problems taking your medication? |

| (13) In case of inhalation therapy: What kind of inhalation system are you using? Are you experiencing any problems using this system? |

| (14) In case of eye drops: Are you experiencing any difficulties using the eye drops? |

| (15) Do you ever forget to take your medication? If so, which medication, why, and what do you do? |

|

|

| Other |

|

|

| (16) Would you like to comment on or ask a question about your medication? |

To improve medication adherence in elderly, a combination of educational and behaviour strategies should always be used [68].

The efficacy and safety of medicines is largely determined by adherence. Adherence is defined as the extent to which a person's behaviour, taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing life-style changes, corresponds with recommendations agreed with a health-care provider [69]. Poor adherence to the treatment of chronic disease is a common problem among the elderly [70]. One of the first articles pointing at the lack of adherence was published in 1957; in only 50% of the patients, who were prescribed tuberculostatics, the drug was found in urine [71]. A Cochrane review reported 50% nonadherence in patients using medicines for chronic diseases [72]. Adherence to antihypertensives and statin therapy is often even lower. Within one year of the start of antihypertensives 50% of the patients have stopped using these drugs [73]. The adherence of elderly patients, prescribed statins, is 60% after 3 months, 43% after 6 months, and 26% after 5 years [74].

The consequences of nonadherence are considerable and include hospital admissions (33–60% of drug related hospital admissions) and higher mortality [21, 75]. Even with use of placebo, high adherence had a 3.5 time greater effect on reducing mortality than the overall active treatment with candesartan in chronic heart failure [76]. This finding suggests that high adherence for taking medicines, is associated with high adherence for life-style advice.

The identification of patient nonadherence is important. Factors that contribute to poor adherence are summarized in Table 4 [9].

Table 4.

Methods of measuring adherence (modified Osterberg and Blaschke [9]).

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Directly observed therapy | Most accurate | Patients can hide pills in mouth and then discard them; impractical for routine use |

| Biochemical measurement of the medicine or metabolite or measurement of a biological marker | Objective | Variations in metabolism and “white coat” adherence can give a false impression; expensive |

| Patient questionnaires or self-reports | Simple, inexpensive, most useful in clinical practice | Susceptible to error and distortion |

| Pill counts | Objective, quantifiable and easy to perform | Data easily altered by the patient (e.g., pill dumping) |

| Rates of prescription refills | Objective, easy to obtain data | A prescription refill is not equivalent to ingestion of medication; requires a closed pharmacy system |

| Assessment of the patient's clinical response | Simple; easy to perform | Factors other than medication adherence can affect clinical response |

| Electronic medication monitors | Precise; results are easily quantified; tracks patterns of taking medication | Expensive for example, MEMs; some requires return visits |

| Measurement of physiologic markers | Often easy to perform | Marker may be absent for other reasons |

| Patient diaries | Help to correct for poor recall | Easily altered by the patient |

| Questionnaire for caregiver, for patients who are cognitively impaired. | Help to correct for poor recall; simple; objective | Susceptible to error and distortion |

A systematic review of barriers to medication adherence in the elderly showed patient-related factors as disease-related knowledge, health literacy and cognitive function, drug-related factors such as adverse effects and polypharmacy [70]. Older person's willingness to take medication for cardiovascular disease prevention is highly sensitive to its adverse effects [77]. Also factors as patient-provider relationship and logistical problems to obtaining medications are identified [70].

In general practice nonadherence is often detected by looking in the medicine cupboard at home. Another method makes use of pharmacy refill records comparing the number of dispensed doses with the number of prescribed doses. A very helpful starting point is to ask the patient and family for the problems they encountered with the drug regimen. The patient should not be blamed for poor adherence. A tool for screening patient adherence is the Brief Medication Questionnaire [78]. Other methods for detecting nonadherence are physiological markers, like low heart-rate with use of beta-blockers, or biochemical measurements in blood or urine such as plasma angiotensin converting enzyme assays to monitor ACEI adherence.

Several methods have been shown to improve adherence. The most effective approach is multilevel targeting at several factors with several interventions. However effective interventions are often complex and not suitable for daily practice. Education in self-management of the drug regimen has limited effects. A simple and very effective method is the reduction of dose frequency. The best adherence is found with a dose frequency of once a day (79%), decreasing to 69% with b.i.d., 65% with t.i.d and 51% with q.i.d [79].

Integrating the patient's perspective into treatment plans is considered to be very important. The behaviour of prescribers is changing from a paternalistic one-way style towards concordance to improve adherence [80].

7.2. Adverse Drug Reactions

Adverse drug events (ADEs) are an important cause of morbidity and mortality in elderly patients [21, 48, 49]. Nursing home and frail elderly patients appear to be at high risk of ADEs. The risk of ADEs is exponentially rather than linearly related to the number of medicines taken. More than 80% of ADEs causing admission or occurring in hospital are type A, that is, they are dose related, predictable, and potentially avoidable. Antibiotics, anticoagulants, digoxin, diuretics, hypoglycaemic agents, antineoplastic agents, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are mainly responsible for type A ADRs. Type B ADRs (idiosyncratic reactions) are less common but can be associated with serious toxicity. Several drugs cause movement disorders and falls in old persons [81, 82]. An approximately linear relationship between the occurrence of ADRs and the number of drugs taken with an 8,6% increase in the risk of ADRs for each additional drugs is found [83]. Table 5 shows common adverse effects of medicines in the elderly. Medication reconciliation reduced by 43% ADE's caused by admission prescribing changes classified as errors [53]. It is important to ask the patient about adverse drug reactions and, if so, to look at alternatives. When drugs have similar efficacy/safety profiles the least expensive option should be prescribed.

Table 5.

Common adverse drug reactions in the elderly.

| Medicine | Adverse drug reaction |

|---|---|

| Anticonvulsants | Drowsiness |

| Anti-parkinsonic drugs | Hallucinations, postural hypotension |

| Antipsychotic drugs | Drowsiness, movement disorders and falls |

| Vitamin K antagonists | Bleeding |

| Digoxin | Nausea, bradycardia, falls |

| Lithium | Delirium, nausea, ataxia, drowsiness nephrotoxicity, thyroid disturbances |

| Opioids | Drowsiness, constipation, falls |

| Sulfonylurea anti-diabetics | Hypoglycemia, falls |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Drowsiness, postural hypotension, movement disorders and falls |

| Verapamil, diltiazem | Bradycardia, hypotension, constipation, falls |

7.3. Undertreatment

The next step is to analyze the problems and diseases of the patient and to determine which drugs are indicated. It is important to identify indicated drugs that are missing. Undertreatment is a common reason for inappropriate prescribing. It has been shown that undertreatment is frequent in elderly patients, despite the use of many medicines [84–86]. The most common areas of undertreatment were extracted from literature, and are presented in Table 6. Choudhury et al. [87] concluded that a physician's experience with bleeding events associated with warfarin in patients can cause underprescription of warfarin to other patients.

Table 6.

Common undertreated conditions and advised medication according to guidelines.

| Disease or problem | Advised medicines |

|---|---|

| Angina pectoris | beta-receptor blocking drug |

| Atrial fibrillation | VKA, when contraindicated acetylsalicylic acid |

| Cardiovascular disease1 | in case of oversensitiveness: clopidogrel, prasugrel |

| Cardiovascular disease + LDL > 2.5 | Statin |

| Cerebral infarction/TIA | Consider antihypertensive treatment, even with normal blood pressure |

| COPD | Inhalation ipratropium or tiotropium/β2-agonists |

| Corticosteroids used > 1 month | Medication to prevent osteoporosis: bisphosphonates |

| Depression | Antidepressants: SSRI's or nortriptyline |

| Diabetes Mellitus | Lipid lowering drugs |

| Diabetes with proteinuria | ACE-inhibitor |

| Heart failure | ACE-inhibitor, or AT II antagonist if necessary beta-receptor blocking drug |

| Hypertension | Anti-hypertensive treatment |

| Insufficient daylight | Vitamin D3 |

| Myocardial Infarction | Acetylsalicylic acid, ACE-inhibitor, beta-receptor blocking drug |

| NSAID | Gastric protection with Proton Pump Inhibitors |

| Opioids | Laxatives |

| Osteoporosis | Antiosteoporosis drugs |

| Pain | Analgesics |

1Cardiovascular disease: by atherothrombotic processes caused clinical manifestations, like myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, cerebral infarction, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), aortic aneurysm, and peripheral arterial vessel disease.

Kuzuya et al. [88] showed that the incidence of polypharmacy among frail community-dwelling older people is lower in the oldest members (>85 years) due to of underuse of medications for chronic diseases. In one study a clear relationship between polypharmacy and underprescription was found [86]. The probability of underprescription increased significantly with the number of medicines.

It appears that general practitioners (GPs) and specialists are not willing to prescribe more drugs to old frail patients with current polypharmacy (e.g., complexity of drug regimens, fear of ADRs, interactions, and poor adherence). Research has shown that for some medical problems a so-called treatment-risk paradox or risk-treatment mismatch exists meaning that patients who are at highest risk for complications have the lowest probability to receive the recommended pharmacological treatment [89, 90]. The application of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) to the care of older patients with several comorbid diseases may have undesirable effects and there could be reasons not to treat all problems. Moreover, the evidence of the benefit of CPG application in elderly patients with comorbid disease is lacking. Boyd et al. [91] estimated that if the relevant CPGs were followed a hypothetical patient would be prescribed 12 medications. However, undertreatment may be harmful for the patient. In optimising polypharmacy, attention should be directed not only to overtreatment but also to possible undertreatment. The aim is to enhance appropriate prescribing to patients with comorbid diseases. In making decisions, prescribers should consider the remaining life expectancy, goals of care and potential benefits of medications [92]. The study of Leliveld-van de Heuvel et al. showed that general practitioners often have reasons not to prescribe a medicine that is advised by guidelines [93].

7.4. Inappropriate Medicines

The indication for a drug is often based on guidelines. However, even if there is an indication for a drug according to the guidelines, it is possible that in specific cases the guidelines can be discarded. In the elderly time-until-benefit and the life expectancy are important factors to consider [92]. Age by itself is no reason to omit drug therapy. To check for contraindicated drugs a list is provided (Table 7). Unnecessary duplications with other drugs should be looked for [48, 60, 61] as well as methods minimizing adverse drug events in older patients [94, 95].

Table 7.

| Disease or problem | Contraindicated drugs |

|---|---|

| COPD | Long acting benzodiazepines, non-selective beta-receptor blocking drugs (e.g., propranolol, carvedilol, labetalol, sotalol) |

| Dementia | Strong acting anticholinergic agents1 |

| Heart failure | Verapamil, diltiazem, short acting nifedipine, NSAIDs, rosiglitazone |

| Lower Urinary Tract Syndrome | Anticholinergic agents1 |

| Active peptic ulcer disease, reflux oesophagitis, or gastritis/duodenitis | NSAIDs |

| Narrow angle glaucoma | Strong acting anticholinergic agents1 |

| Constipation | Verapamil, diltiazem, anticholinergic agents1 |

| Postural hypotension | Tricyclic antidepressants |

| Parkinson's disease | Metoclopramide, all antipsychotics except clozapine and quetiapine |

| Hyponatremia (SIADH) | SSRIs |

| Falls | Psychoactive drugs |

1Strong acting anticholinergic drugs: spasmolytics, tricyclic antidepressants, and anticholinergic antiparkinsonic drugs.

7.5. Drug Interactions

Although around 10% of the general population take more than one prescribed medicine, the incidence of combination therapy is greatest in the elderly, in females, and in those who have had a recent hospital admission. Patients aged over 65 years use on average four prescribed medications. The medicines should be prescribable together. It is important to look at clinically significant drug-drug and drug-disease interactions [12].

A list of common drug interactions in elderly patients is illustrated in Table 8.

Table 8.

The most common drug interactions in elderly patients [12].

| Drug | Interaction | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| ACE inhibitors | NSAIDs, Coxibs, potassium-sparing diuretics | Decreased renal function, hyperkalemia |

| Antidepressants | Enzyme inducers1 | Less antidepressant effect |

| Antihypertensives | Vasodilators, antipsychotic drug, tricyclic antidepressants | Increased antihypertensive effect |

| NSAIDs | Decreased antihypertensive effect | |

| Beta-receptor-blocking drugs | Anti-diabetic drugs | Masks hypoglycemia |

| Fluoxetine, paroxetine (especially in combination with metoprolol and propranolol) | Bradycardia | |

| Corticosteroids (oral) | NSAIDs | Gastro-duodenal ulcer disease |

| enzyme inducers1 | Decreased corticosteroid effect | |

| Digoxin | NSAIDs, diuretics, qinidine, verapamil, diltiazem, amiodarone | Digoxin intoxication |

| Fluoroquinolones | Al-Mg containing antacids, iron, calcium | Decreased bioavailability |

| Levodopa | Iron | Decreased bioavailability |

| Lithium | NSAIDs, thiazide diuretics, antipsychotics | Lithium toxicity |

| Phenytoin | Enzyme inhibitors2 | Increased toxicity |

| Sulfonylurea anti-diabetics | SSRIs, chloramphenicol, VKA's, phenylbutazone | Hypoglycemia |

| SSRIs | Diuretics, NSAIDs | Hyponatremia, gastric bleeding |

| Tetracyclines | Antacids, iron | Decreased bioavailability |

| VKA's | Acetylsalicylic acid, NSAIDs, metronidazole, miconazole and other azole-type drugs | Bleeding |

1Important enzyme inducers: carbamazepine, rifampicin, phenobarbital, phenytoin, St. John's wort.

2Important enzyme inhibitors: verapamil, diltiazem, amiodarone, fluconazole, miconazole, ketoconazole, erythromycin, claritromycin, sulfonamides, cimetidine, ciprofloxacin, and grapefruit juice.

Patients should be advised not to drink grapefruit juice or pay attention to ADRs if they are using any of the following drugs:

-

Antiarrhythmic agents: quinidine.

-

Histamine antagonists: Astemizole, Terfenadine.

-

Benzodiazepines: Alprazolam, Diazepam, Midazolam, Triazolam.

-

Calcium channel blockers: Diltiazem, Felodipine, Nifedipine, Verapamil, Lercanidipine, Nitrendipine.

-

HIV medication: Indinavir, Nelfinavir, Ritonavir, Saquinavir.

-

Hormones: Estradiol, Hydrocortisone, Progesterone, Testosterone.

-

Immune modulators: Cyclosporine, Tacrolimus.

-

Macrolide antibiotics: Claritromycin and erythromycin.

-

Statins: atorvastatin, simvastatin.

-

Other: Aripiprazole, Buspirone, Dexamethasone, Docetaxel, Domperidone, Fentanyl, Haloperidol, Irinotecan, Propranolol, Risperidone, Salmeterol, Tamoxifen, Taxol, Vincristine, Zolpidem.

For the clinically relevant interactions with St. John's wort see Table 2.

7.6. Dose and/or Dose Frequency Adjustment

Consider if the prescribed dose is still correct. In elderly patients serum creatinine may be within the reference limits, while renal function is markedly diminished. The Cockcroft and Gault and/or the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equations may be helpful for a better estimation of glomerular filtration rate for drugs cleared predominantly renally. However, there are concerns about the validity of these methods in frail elderly. A list of drugs whose dosage should be adjusted in case of decreased renal function is presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Adjustment of dosage in renal insufficiency. Calculate the creatinine clearance or GFR (http://nephron.com/cgi-bin/CGSI.cgi). For Crcl < 10 mL/min consult the nephrologist.

| Decreased renal function and dose adjustment | |

|---|---|

| ACE Inhibitors | |

| Benazepril | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: start with 2.5–5 mg once daily. Adjust dosage based on effect. |

| Captopril | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: start with 12.5–25 mg once daily. Adjust dosage based on effect until 75–100 mg/day |

| Cilazapril | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: start with max. 0.5 mg/day. Adjust dosage based on effect until max. 2.5 mg/day |

| Enalapril | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: start with max. 5 mg/day. Adjust dosage based on effect until max. 10 mg/day |

| Lisinopril | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: start with max. 5 mg/day. Adjust dosage based on effect until max. 40 mg/day |

| Perindopril | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: max. 2 mg/day; Clcr 10–30 mL/min: max. 2 mg every two days |

| Quinapril | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: start with 5 mg/day; Clcr 10–30 mL/min: start with 2.5 mg/day. Adjust dosage based on effect. |

| Ramipril | Clcr 20–50 mL/min: start with max. 1.25 mg/day. Adjust dosage based on effect. |

| Clcr 10–20 mL/min: insufficient data for sound advise | |

| Trandolapril | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: start with max. 0.5 mg/day. Adjust dosage based on effect until max. 2 mg/day |

| Zofenopril | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: start with max. 7.5 mg/day. Adjust dosage based on effect until max. 15 mg/day |

|

| |

| Antibiotics | |

| Cephalosporins | |

| Cephalexin | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: prolong interval to once per every 12 hours. |

| Cephalothin | Clcr 50–80 mL/min 2 g every 6 hours; 30–50 mL/min 1.5 g every 6 hours; 10–30 mL/min 1 g every 8 hours. |

| Cephamandole | Clcr 50–80 mL/min 2 g every 6 hours, in case of life-threatening infection 1.5 g every 4 hours; |

| Clcr 30–50 mL/min 2 g every 8 hours, in case of life-threatening infection 1.5 g every 6 hours; | |

| Clcr 10–30 mL/min 1.25 g every 6 hours, in case of life-threatening infection 1 g every 6 hours. | |

| Cephazolin | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: 500 mg every 12 hours; 10–30 mL/min: 500 mg every 24 hours. |

| Cephradine | Clcr <30 mL/min: contra-indicated |

| Cephtazidime | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: 1 g every 12 hours; 10–30 mL min: 1 g every 24 hours. |

| Cephtibuten | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: 200 mg every 24 hours; 10–30 mL/min: 100 mg every 24 hours. |

| Cephuroxime parenteral | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: standard dosage every 12 hours. |

|

| |

| Fluoroquinolones | |

| Ciprofloxacin | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage |

| Levofloxacin; ofloxacin | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage; Clcr 10–30 mL/min: 25% of normal dosage |

| Norfloxacin | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: prolong interval to once every 24 hours |

|

| |

| Nitrofurantoin | |

| Nitrofurantoin | Clcr < 50: contra-indicated. Risk of neuropathy and failure of therapy. |

|

| |

| Macrolide | |

| Claritromycin | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage with normal dose frequency |

|

| |

| Penicillins | |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: standard dosage every 12 hours (orally, i.v. of.im.) |

| Benzylpenicillin | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: dosage dependent of indication. Consider intended effect, risks of overdosage and underdosage. |

| Piperacillin | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: max. 12 g per day in 3 or 4 doses; Clcr 10–30 mL/min: max. 8 g per day in 2 doses |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: piperacillin/tazobactam 12 g/1.5 g per day in 3 or 4 doses Clcr 10–30 mL/min: piperacillin 4 g/0.5 g every 12 hours |

|

| |

| Tetracyclines | |

| Tetracycline | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: maintenance dosage 250 mg once daily |

|

| |

| Antidiabetics | |

| Metformin | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: start with twice daily 500 mg; Clcr 10–<30 mL/min: contraindicated |

| Sulfonylurea (e.g., Tolbutamide) | Clcr < 50 mL/min start with half the dosage |

|

| |

| Antihistaminics | |

| Acrivastine | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage OR prolong interval to 1-2x per day |

| Cetirizine/Levocetirizine/Hydroxyzine/ Fexofenadine/Terfenadine |

Clcr 10–50 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage |

|

| |

| Antimycotics | |

| Fluconazole | In case of >once daily dosing regimen: Clcr 10–50 mL/min: normal starting dosage, decrease maintenance dosage until 50% of normal dosage |

| Flucytosine | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: prolong interval to once every 12 hours, then based on serum plasma concentration |

| Clcr 10–30 mL/min: prolong interval to once every 24 hours, then based on serum plasma concentration | |

| Terbinafine | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage |

|

| |

| Antiparkinson drugs | |

| Pramipexole | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: start with 0.125 mg (= 0.088 base) twice daily, then based on effect/adverse events |

| Clcr 10–30 mL/min: start with 0.125 mg (= 0.088 base) once daily, then based on effect/adverse events | |

|

| |

| Antithrombotics | |

| Dabigatran | Clcr <30 mL/min: contra-indicated |

| Eptifibatide | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: normal starting dosage, then 50% of normal dosage |

| Tirofiban | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage |

|

| |

| Antiviral medication | |

| Acyclovir orally | Decrease dosage used for herpes zoster treatment: Clcr 10–30 mL/min: 800 mg 3 times a day |

| Amantadine | Start with 200 mg, maintenance dosage: Clcr 50–80 mL/min: 100 mg once daily; |

| Clcr 30–50 mL/min: 100 mg every 2 days; Clcr 10–30 mL/min 100 mg every 3 days. | |

| Cidofovir | Clcr <50 mL/min: preferably do not use |

| Famciclovir | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: normal dosage every 24 hours; 10–30 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage every 24 hours |

| Foscarnet | Clcr 30–80 mL/min: dosage according to schedule manufacturer; <30 mL/min: do not use |

| Ganciclovir | Induction: Clcr 50–80 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage every 12 hours; 30–50 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage every 24 hours; 10–30 mL/min: 25% of normal dosage every 24 hours |

| Maintenance: Clcr 50–80 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage every 24 hours; 30–50 mL/min: 25% of normal dosage every 24 hours; 10–30 mL/min: 12.5% of normal dosage every 24 hours | |

| Oseltamivir | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage OR normal dosage but double interval |

| Ribavirin | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: dosage based on hemoglobin concentration |

| Valaciclovir | Clcr 10–80 mL/min: adjust dosage according to schedule manufacturer |

| Valganciclovir | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage plus double interval |

| Clcr 10–30 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage twice a week | |

|

| |

| Beta-receptor-blocking drugs | |

| Acebutolol; Atenolol | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage |

| Bisoprolol | Clcr 10–20 mL/min: start with 50% of normal dosage. Then max. 10 mg/day |

| Sotalol | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: max 160 mg/day; Clcr 10–30 mL/min: max. 80 mg/day |

|

| |

| Calcium antagonists, dihydropyridine type | |

| Barnidipine | Clcr <50 mL/min: contraindicated |

|

| |

| Digoxin | |

| Digoxin | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: decrease initial dosage by 50%, then go to 0.125 mg/day. Next adjust dosage based on clinical symptoms |

|

| |

| DMARDs | |

| Anakinra | Clcr < 30 mL/min: contraindicated |

| Methotrexate | Clcr 40–70 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage. Clcr < 40 mL/min: based on serum plasma concentration |

|

| |

| Gout medication | |

| Allopurinol | Clcr 50–80 mL/min: 300 mg/day; 30–50 mL/min: 200 mg/day; 10–30 mL/min: 100 mg/day |

| Benzbromarone | Clcr <30 mL/min: contraindicated |

| Colchicine | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: 0.5 mg/day |

|

| |

| H2-antagonists | |

| Nizatidine; cimetidine; famotidine; ranitidine | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage, once daily |

|

| |

| Hypnotics, sedative agents, anxiolytic drugs, Antipsychotics | |

| Chloralhydrate | Clcr <50 mL/min: preferably do not use |

| Meprobamate | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage OR double dosage interval |

| Risperidone | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage, then based on effect and adverse events |

|

| |

| Muscle relaxants | |

| Baclofen | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: start with 5 mg once daily, then adjust based on effect and adverse events. |

| Tizanidine | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: start with 2 mg once daily, then increase dosage slowly based on effect and adverse events. End with increasing the dose frequency. |

| NSAIDs | All NSAID's: Clcr < 30 mL/min: consider if chronic use is indicated. Check renal function previously to and 1 week after start |

|

| |

| OPIOIDs | |

| Morphine | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: dosage based on effect and adverse events. Be alert to accumulation of M6G |

| Tramadol | Clcr 10–30 mL/min: decrease dose frequency to 2-3 x per day In case of retard tablet max. 200 mg per day |

|

| |

| Tuberculostatics | |

| Ethambutol | Clcr 10–50 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage |

|

| |

| Vertigo medication | |

| Piracetam | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: 50% of normal dosage; Clcr 10–30 mL/min: 25% of normal dosage |

|

| |

| Xanthine derivates | |

| Pentoxifylline | Clcr 30–50 mL/min: 400 mg twice daily; Clcr 10–30 mL/min: 400 mg once daily |

This question also serves to make physicians aware of the possibility to decrease the dose frequency, or to combine drugs in combination preparates in order to improve adherence.

Adherence can be increased in several ways, but most evidence exists for reduction of the number of daily doses [72].

Recently the polypharmacy optimization method (POM) has been incorporated in the Polypharmacy guideline in the Netherlands. The POM has become part, as step 1 and 2, of the structured tool to reduce inappropriate polypharmacy (STRIP). The STRIP consists of five steps:

Structured history taking of medication, for example according to SHIM [8].

Pharmacotherapeutic analysis consisting of analysis of undertreatment, effectiveness of the used medicines, no longer indicated drugs, presence of adverse drug reactions, presence of clinically relevant interactions, necessity to correct the prescribed dose, presence of problems with the use of the medicines.

Setting up a pharmacotherapeutical treatment plan, together by physician and pharmacist.

Discuss the pharmacotherapeutical plan with the patient and make definite decisions.

Monitor the consequences of the plan and make adaptations if necessary.

8. Conclusion

Older persons have a significantly higher disease burden compared with younger adults, and they consume almost half of total drug expenditures. Because of the changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics with aging, and the increase risk for ADRs there is a need for more clinical and observational studies in the elderly. Underrepresentation of older patients in clinical trials is still reported and may occur for many reasons, but major factors are believed to be exclusions due to comorbid conditions, the use of concomitant medications, and frail health [96–98]. However, even the best preauthorization study cannot answer all the possible questions. Hence, postauthorization studies and ways to examine clinical practice generated information are needed. This is recognised also by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicine Agency (EMA). The EMA's Committee for Medicinal Products for Human use (CHMP) has established a Geriatric Expert Group, to provide scientific advice on issues related to the elderly. An European Geriatic Medicine Strategy is launched in 2011. Information is available on http://www.ema.europa.eu/. In The Netherlands the Expertise centre Pharmacotherapy in Old Persons is raised to improve effective and as safe as possible pharmacotherapy (http://www.ephor.eu). Adequate information is critical for optimal patient-individualized drug use. A multifaceted approach will be required to improve the evidence base to guide prescribers. Use of the STRIP method may help prescribers to optimize polypharmacy. Specific gerontopharmacology education is needed to teach students and prescribers, how to optimize polypharmacy and prescribe appropriate medication to old persons [99].

References

- 1.Lutz W, Sanderson W, Scherbov S. The coming acceleration of global population ageing. Nature. 2008;451(7179):716–719. doi: 10.1038/nature06516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations, Department of Economic, Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects: the 2010 Revision. New York, http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/population-pyramids/population-pyramids.htm, 2011.

- 3.Kirkwood TA. Systematic look at an old problem. As life expectancy increases, a systems-biology approach is neede to ensure that we have a healthy old age. Nature. 2008;451:644–647. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mangoni A, Jansen P, Jackson S. Clinical pharmacology of ageing. In: Jackson S, Jansen P, Mangoni A, editors. Prescribing For Eldely Patients. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gainsborough N, Maskrey VL, Nelson ML, et al. The association of age with gastric emptying. Age and Ageing. 1993;22(1):37–40. doi: 10.1093/ageing/22.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkinson GR. The effects of diet, aging and disease-states on presystemic elimination and oral drug bioavailability in humans. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 1997;27(2-3):129–159. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang SM, Hall SD, Watkins P, et al. Drug interactions with herbal products and grapefruit juice: a conference report. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2004;75(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drenth-van Maanen AC, Spee J, van Marum RJ, Egberts ACG, van Hensbergen L, Jansen PAF. Iatrogenic harm due to discrepancies in medication histories in hospital and pharmacy records revealed by structured history taking of medication use. The Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59:1976–1977. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03610_11.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pariente A, Dartigues JF, Benichou J, Letenneur L, Moore N, Fourrier-Réglat A. Benzodiazepines and injurious falls in community dwelling elders. Drugs and Aging. 2008;25(1):61–70. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, McGlinchey RE. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(5):508–513. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drenth-Van Maanen AC, Van Marum RJ, Knol W, Van Der Linden CMJ, Jansen PAF. Prescribing optimization method for improving prescribing in elderly patients receiving polypharmacy: results of application to case histories by general practitioners. Drugs and Aging. 2009;26(8):687–701. doi: 10.2165/11316400-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benet LZ, Hoener BA. Changes in plasma protein binding have little clinical relevance. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2002;71(3):115–121. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.121829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musteata FM. Calculation of normalized drug concentrations in the presence of altered plasma protein binding. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 2012;51:55–68. doi: 10.2165/11595650-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeeh J, Platt D. The aging liver: structural and functional changes and their consequences for drug treatment in old age. Gerontology. 2002;48(3):121–127. doi: 10.1159/000052829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sotaniemi EA, Arranto AJ, Pelkonen O, Pasanen M. Age and cytochrome P450-linked drug metabolism in humans: an analysis of 226 subjects with equal histopathologic conditions. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1997;61(3):331–339. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Marcheix A, Bouthier F, Merle L. Estimation of glomerular filtration rate in the elderly: cockcroft-Gault formula versus modification of diet in renal disease formula. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(7 I):1041–1046. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.7.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedone C, Corsonello A, Incalzi RA. Estimating renal function in older people: a comparison of three formulas. Age and Ageing. 2006;35(2):121–126. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afj041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsushita K, Mahmoodi BK, Woodward M, et al. Comparison of risk prediction using the CKD-EPI Equation and the MDRD study equation for estimated glomerular filtration rate. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307:1941–1951. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowie MW, Slattum PW. Pharmacodynamics in Older Adults: a Review. American Journal Geriatric Pharmacotherapy. 2007;5(3):263–303. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leendertse AJ, Egberts ACG, Stoker LJ, Van Den Bemt PMLA. Frequency of and risk factors for preventable medication-related hospital admissions in the Netherlands. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(17):1890–1896. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poli D, Antonucci E, Testa S, Tosetto A, Ageno W, Palareti G. Bleeding risk in very old patients on Vitamin K antagonist treatment: results of a prospective collaborative study on elderly patients followed by italian centres for anticoagulation. Circulation. 2011;124:824–829. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.007864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bauersachs RM. Use of anticoagulants in elderly patients. Thrombosis Research. 2012;129:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montamat SC, Abernethy DR. Calcium antagonists in geriatric patients: diltiazem in elderly persons with hypertension. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1989;45(6):682–691. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1989.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robin DW, Hasan SS, Edeki T, Lichtenstein MJ, Shiavi RG, Wood AJJ. Increased baseline sway contributes to increased losses of balance in older people following triazolam. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1996;44(3):300–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albrecht S, Ihmsen H, Hering W, et al. The effect of age on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of midazolam. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1999;65(6):630–639. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(99)90084-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toornvliet R, van Berckel BNM, Luurtsema G, et al. Effect of age on functional P-glycoprotein in the blood-brain barrier measured by use of (R)-[11C]verapamil and positron emission tomography. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2006;79(6):540–548. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kazama T, Takeuchi K, Ikeda K, et al. Optimal propofol plasma concentration during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in young, middle-aged, and elderly patients. Anesthesiology. 2000;93(3):662–669. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200009000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott JC, Stanski DR. Decreased fentanyl and alfentanil dose requirements with age. A simultaneous pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1987;240(1):159–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minto CF, Schnider TW, Egan TD, et al. Influence of age and gender on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of remifentanil I. Model development. Anesthesiology. 1997;86(1):10–23. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199701000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLachlan AJ, Hilmer SN, Le Couteur DG. Variability in response to medicines in older people: phenotypic and genotypic factors. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2009;85(4):431–433. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleijer BC, Van Marum RJ, Egberts ACG, et al. The course of behavioral problems in elderly nursing home patients with dementia when treated with antipsychotics. International Psychogeriatrics. 2009;21(5):931–940. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knol W, van Marum R, Jansen P, Egberts A, Schobben A. Haloperidol induced parkinsonism in elderly patients: relation with dose, plasma concentration and duration of use. In: Knol W, editor. Antipsychotic Induced Parkinsonism in the Elderly: Assessment, Causes and Consequences. Enschede, The Netherlands: Gildeprint; 2011. pp. 60–73. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miao L, Yang J, Huang C, Shen Z. Contribution of age, body weight, and CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotype to the anticoagulant response to warfarin: proposal for a new dosing regimen in Chinese patients. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2007;63(12):1135–1141. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beinema M, Brouwers JRBJ, Schalekamp T, Wilffert B. Pharmacogenetic differences between warfarin, acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2008;100(6):1052–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans WE, McLeod HL. Pharmacogenomics—drug disposition, drug targets, and side effects. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348(6):538–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hilmer SN, McLachlan AJ, Le Couteur DG. Clinical pharmacology in the geriatric patient. Fundamental and Clinical Pharmacology. 2007;21(3):217–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2007.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. Journals of Gerontology A. 2001;56(3):M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgan ET, Goralski KB, Piquette-Miller M, et al. Regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in infection, inflammation, and cancer. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2008;36(2):205–216. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.018747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zahn JM, Poosala S, Owen AB, et al. AGEMAP: a gene expression database for aging in mice. PLoS genetics. 2007;3(11):p. e201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Francis SA, Barnett N, Denham M. Switching of prescription drugs to over-the-counter status. Is it a good thing for the elderly? Drugs and Aging. 2005;22(5):361–370. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cebollero-Santamaria F, Smith J, Gioe S, et al. Selective outpatient management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the elderly. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1999;94(5):1242–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewis JD, Kimmel SE, Localio AR, et al. Risk of serious upper gastrointestinal toxicity with over-the-counter nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(6):1865–1874. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oborne CA, Luzac ML. Over-the-counter medicine use prior to and during hospitalization. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2005;39(2):268–273. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sergi G, De Rui M, Sarti S, Manzato E. Polypharmacy in the elderly: can comprehensive geriatric assessment reduce inappropriate medication use? Drugs and Aging. 2011;28(7):509–518. doi: 10.2165/11592010-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dedhiya SD, Hancock E, Craig BA, Doebbeling CC, Thomas J. Incident use and outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. American Journal Geriatric Pharmacotherapy. 2010;8(6):562–570. doi: 10.1016/S1543-5946(10)80005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beijer HJM, De Blaey CJ. Hospitalisations caused by adverse drug reactions (ADR): a meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharmacy World and Science. 2002;24(2):46–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1015570104121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. British Medical Journal. 2004;329(7456):15–19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rogers S, Wilson D, Wan S, Griffin M, Rai G, Farrell J. Medication-related admissions in older people: a cross-sectional, observational Study. Drugs and Aging. 2009;26(11):951–961. doi: 10.2165/11316750-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rollason V, Vogt N. Reduction of polypharmacy in the elderly: a systematic review of the role of the pharmacist. Drugs and Aging. 2003;20(11):817–832. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200320110-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pitkala KH, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS. Is it possible to reduce polypharmacy in the elderly? A randomised, controlled trial. Drugs and Aging. 2001;18(2):143–149. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogers G, Alper E, Brunelle D, et al. Reconciling medications at admission: safe practice recommendations and implementation strategies. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2006;32(1):37–50. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boockvar KS, Blum S, Kugler A, et al. Effect of admission medication reconciliation on adverse drug events from admission medication changes. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(9):860–861. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shelton PS, Fritsch MA, Scott MA. Assessing medication appropriateness in the elderly. A review of available measures. Drugs and Aging. 2000;16(6):437–450. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200016060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? The Lancet. 2007;370(9582):173–184. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45(10):1045–1051. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90144-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fick D, Semla T, Beizer J, et al. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(4):616–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McLeod PJ, Huang AR, Tamblyn RM, Gayton DC. Defining inappropriate practices in prescribing for elderly people: a national consensus panel. CMAJ. 1997;156(3):385–391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laroche ML, Bouthier F, Merle L, Charmes JP. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: interest of a list adapted to the French medical practice. Revue de Medecine Interne. 2009;30(7):592–601. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rognstad S, Brekke M, Fetveit A, Spigset O, Wyller TB, Straand J. The norwegian general practice (NORGEP) criteria for assessing potentially inappropriate prescriptions to elderly patients. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 2009;27(3):153–159. doi: 10.1080/02813430902992215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barry PJ, Gallagher P, Ryan C, O’mahony D. START (screening tool to alert doctors to the right treatment)—an evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patients. Age and Ageing. 2007;36(6):632–638. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Kennedy J, O’Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Consensus validation. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2008;46(2):72–83. doi: 10.5414/cpp46072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hamilton H, Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, O’Mahony D. Potentially inappropriate medications defined by STOPP criteria and the risk of adverse drug events in older hospitalized patients. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(11):1013–1019. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gleason KM, McDaniel MR, Feinglass J, et al. Results of the medications at transitions and clinical handoffs (match) study: an analysis of medication reconciliation errors and risk factors at hospital admission. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(5):441–447. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1256-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fitzgerald RJ. Medication errors: the importance of an accurate drug history. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2009;67(6):671–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03424.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Doty RL, Shah M, Bromley SM. Drug-induced taste disorders. Drug Safety. 2008;31(3):199–215. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schiffman SS. Effects of aging on the human taste system. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1170:725–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.George J, Elliott RA, Stewart DC. A systematic review of interventions to improve medication taking in elderly patients prescribed multiple medications. Drugs and Aging. 2008;25(4):307–324. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Geest S, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2003;2(4):p. 323. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gellad WF, Grenard JL, Marcum ZA. A systematic review of barriers to medication adherence in the elderly: looking beyond cost and regimen complexity. American Journal Geriatric Pharmacotherapy. 2011;9(1):11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dixon WM, Stradling P, Wootton IDP. Outpatient P.A.S. therapy. The Lancet. 1957;270(7001):871–872. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(57)90006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haynes R, McDonald H, Garg A, Monaque P. Interventions for helping patients to follow their prescriptions for medications. The Chochrane Library. 2005;(1) [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bloom BS. Daily regimen and compliance with treatment: fewer daily doses and drugs with fewer side effects improve compliance. British Medical Journal. 2001;323(7314):p. 647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7314.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Benner JS, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Neumann PJ, Weinstein MC, Avorn J. Long-term persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patients. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(4):455–461. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McDonnell PJ, Jacobs MR, Monsanto HA, Kaiser JM. Hospital admissions resulting from preventable adverse drug reactions. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2002;36(9):1331–1336. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Granger BB, Swedberg K, Ekman I, et al. Adherence to candesartan and placebo and outcomes in chronic heart failure in the CHARM programme: double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical trial. The Lancet. 2005;366(9502):2005–2011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67760-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Towle V, O’Leary JR, Iannone L. Effects of benefits and harms on older persons’ willingness to take medication for primary cardiovascular prevention. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(10):923–928. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Svarstad BL, Chewning BA, Sleath BL, Claesson C. The brief medication questionnaire: a tool for screening patient adherence and barriers to adherence. Patient Education and Counseling. 1999;37(2):113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clinical Therapeutics. 2001;23(8):1296–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bissell P, May CR, Noyce PR. From compliance to concordance: barriers to accomplishing a re-framed model of health care interactions. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;58(4):851–862. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]