Abstract

The digestion of prey by carnivorous plants is determined in part by suites of enzymes that are associated with morphologically and anatomically diverse trapping mechanisms. Chitinases represent a group of enzymes known to be integral to effective plant carnivory. In non-carnivorous plants, chitinases commonly act as pathogenesis-related proteins, which are either induced in response to insect herbivory and fungal elicitors, or constitutively expressed in tissues vulnerable to attack. In the Caryophyllales carnivorous plant lineage, multiple classes of chitinases are likely involved in both pathogenic response and digestion of prey items. We review what is currently known about trap morphologies, provide an examination of the diversity, roles, and evolution of chitinases, and examine how herbivore and pathogen defense mechanisms may have been coopted for plant carnivory in the Caryophyllales.

Introduction

The ability by which carnivorous plants capture and digest their prey has been a topic of great interest for over a century. The earliest investigations of digestive enzymes involved in plant carnivory began with Sir Joseph Hooker’s studies of protease activity in the trap fluid of Nepenthes, the tropical pitcher plant [1,2]. Charles Darwin soon published his own account of the sundew, Drosera, and its ability to digest nitrogenous and phosphate-containing compounds with use of its multicellular glands located on the leaf blade [3]. It was not until almost 100 years later that the basic enzyme activity of carnivorous plant mucilage was characterized for a number of species [4–8], and more recent studies have successfully characterized the amino acid sequences that code for carnivorous plant digestive enzymes via comparative annotation of digestive fluid proteomes [8] and trap transcriptomes [9••]. Many of these studies on the role of digestive enzymes in plant carnivory have focused on members of the Caryophyllales, which include the Venus flytrap (Dionaea), sundews (Drosera), and tropical pitcher plants (Nepenthes), among others [4,10–13,14••,15••]. Most recently, molecular evolutionary studies have reconstructed phylogenetic relationships among certain classes of chitinolytic enzymes [14••,15••], and interpreted signatures of selection that infer the cooption of class I chitinases to function in plant carnivory [14••].

Many of the organs and biochemical compounds that these carnivorous plants use for trapping, digesting, and absorbing are similar in structure and function to those found in closely related non-carnivorous plants. Increasing evidence suggests that physical and chemical mechanisms used in defense against herbivores and pathogens have evolved to function in plant carnivory, especially within the carnivorous Caryophyllales. In this paper, we review newly interpreted data on gland morphology and anatomy, we investigate the roles of chitinases within the trap, and we discuss how mechanisms originally used for defense may have evolved to also function in maintaining an effective carnivorous habit.

Morphological adaptations

Sessile, staked, and pitted multicellular glands

The noncore Caryophyllales include a lineage of carnivorous plants comprised of families Droseraceae (Aldrovanda, Dionaea, Drosera), Drosophyllaceae (Drosophyllum), Nepenthaceae (Nepenthes), part-time carnivore Dioncophyllaceae (Triphyophyllum), in addition to closely related members that have lost the carnivorous habit: Ancistrocladaceae (Ancistrocladus), Dioncophyllaceae (Dioncophyllum and Habropetalum). Most recent phylogenetic analyses have recovered families Droseraceae, Nepenthaceae, and a clade comprised of Ancistrocladaceae, Dioncophyllaceae, and Drosophyllaceae as monophyletic [16••].

Shared among the noncore Caryophyllales is the presence of various types of multicellular glands that are distributed across the above-ground portion of the plant. In carnivorous taxa, specific multicellular glands are associated with leaves that have been modified to capture prey, and these glands function in the secretion of digestive enzymes as well as the absorption of amino acids and other organic nutrients. These multicellular glands can be sessile, stalked, or pitted, and may contain xylem and phloem. While the presence of vasculature is not a strong indicator of functional carnivory as many carnivorous glands are not vascularized (e.g. glands types of Dionaea, Aldrovanda, and Nepenthes) (Figure 1) [16••], the multicellular glands thus far characterized in the non-carnivorous outgroups do not appear to have associated vasculature (Figure 1). Ancestral state reconstruction suggests that sessile glands without vasculature are likely the ancestral state for the carnivorous Caryophyllales, while stalked and pitted glands were acquired secondarily and independently by the non-carnivorous sister families and by various lineages of carnivores [16••]. Such independent origins are reflected in differences in vascularization and overall gland morphology (e.g. stalked glands, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of multicellular glands associated with plant carnivory in the Caryophyllales. Multicellular glands involved in plant carnivory are either sessile, stalked, or pitted, and may contain either xylem or phloem. Phylogenetic relationships depicted among major carnivorous plant genera of the Caryophyllales are based upon maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference analyses and character states refer to stochastic character mapping of gland states [16••]. Gray in the phylogeny represents non-carnivorous taxa, while black represent carnivorous taxa. Illustrations located below character states depict examples of gland types for members of the carnivorous Caryophyllales and outgroup Plumbaginaceae (not to scale). For more detail in regard to gland morphologies, see [16••,17–19,21,64].

The morphology of multicellular glands and associated chemistry in non-carnivorous families sister to the carnivorous Caryophyllales may provide clues to the ancestral conditions that preceded the evolution of glands used specifically for plant carnivory. Tamaricaceae, Frankeniaceae, Polygonaceae and Plumbaginaceae (i.e. families sister to the carnivorous Caryophyllales) maintain a variety of sessile, stalked, and pitted glands that are rarely vascularized, but often occur near vascular tissue (Figure 1) [17–19]. These glands are known to exude salt or mucilage, provide protection in halophytic conditions, function in seed dispersal, and deter herbivory [17,20,21,19,22]. Mucilage-producing glands found on some Plumbaginaceae inflorescences have been witnessed to capture insects [23] and are known to secrete proteolytic enzymes when stimulated by NaCl, NH4Cl, or KCl [24]. Yet there is no strong evidence that the secretion of digestive enzymes is stimulated or induced by captured insects [24], nor have experiments been conducted to determine whether the materials digested by these enzymes are actively absorbed by the plant. Such glands, however, could serve as the morphological precursors to the actively secreting and absorbing glands found in the carnivorous lineages.

Sticky glands are used by plants that are considered to be ‘paracarnivorous’; plants that can immobilize insects but lack additional features that associated with plant carnivory, such as the production of digestive enzymes or absorption of nutrients. Roridula (Ericales) has an interesting digestive mutualism with hemipteran insects, in which the hemipterans consume insects trapped by the plant’s secretory trichomes and deposit feces rich in nitrogen into gaps in the cuticle of the leaf [25]. The glands themselves do not exude digestive enzymes [26]. Additionally, although the tank trichomes of Brocchinia (Bromeliaceae) have been demonstrated to absorb water and nutrients, they do not produce enzymes [27,28]. Such taxa may be examples of plants that are currently utilizing certain morphologies derived for defense in a way that is evolving toward plant carnivory.

In addition to glands that exude and absorb, plants have a variety of insect repellent surfaces that inhibit attachment or slow movement [29]. In carnivorous plant traps, leaf surfaces are modified to aid in the capture of prey. For example, Nepenthes pitchers have at least two forms of slippery surfaces: firstly, inner pitcher walls and lids with wax crystals [30••,31••], and secondly, peristomes with inward-facing trichomes that are extremely wettable. Similar functionalities of wax and hairs have also been reported for bromeliads leaves [32] and the inner walls of Heliamphora (Ericales) pitchers [33•].

Cooption of digestive enzymes

Chitinases for plant carnivory in the Caryophyllales

Functioning in the hydrolysis of β-1,4-glycosidic bonds between N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) oligomers in chitin polymers [34], chitinases commonly act as pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins in plants and are either induced in response to insect herbivory and fungal elicitors, or constitutively expressed in tissues vulnerable to attack [35,36]. Plant chitinases are encoded by large gene families and are organized into five classes: classes I (further divided into subclasses Ia and Ib), II, and IV chitinases share a homologous catalytic domain as well as a signal peptide at the amino terminus, while classes III and V are more similar to fungal and bacterial chitinases and have been found to exhibit additional lysozyme activities [37–39]. It is also important to note that subclass Ia has a carboxyl terminal extension (CTE) that codes for transmission to the vacuole, while subclass Ib is extra-cellular due to the absence of a CTE [40,41]. Classes I–V have been identified in all non-carnivorous plants analyzed to date, many of which inhibit fungal growth and can enhance resistance to fungal pathogens in transgenic plants [35,42–44].

In addition to playing a role in herbivore and pathogenic response, chitinases are demonstrated to be important for plant carnivory. Chitinolytic activity was first broadly characterized for Dionaea, Drosera, and Nepenthes in which digestion of chitin was shown to increase over time in the presence of trap secretions [4,45]. However, none of these early studies could rule out the possibility that microorganisms were responsible for the activity. It was not until sequences were obtained and expression localized to digestive glands that it was confirmed that the chitinases are endogenous to the plants themselves [6–8,14••,46].

In Nepenthes khasiana, subclasses Ia and Ib chitinases are present in the pitcher, each of which have differential expression patterns. Subclass Ia are constitutively expressed in the secretory tissues, whereas subclass Ib are upregulated in response to chitin and secreted into the pitcher fluid [7]. As non-carnivorous plant subclass Ib chitinases are excreted into the intercellular space due to the absence of a CTE [40,41], it is thought that the lack of a CTE also allows for excretion from the carnivorous glands for prey digestion [7,14••]. Similarly, in Drosera rotundifolia, class I chitinases are upregulated following induction with chitin and have been localized to the sessile and stalked multicellular glands [6]. More recently, additional class I chitinase genes have been sequenced across the carnivorous Caryophyllales for Dionaea, Drosera and Nepenthes, and Triphyophyllum, as well as for members of the closely related non-carnivorous genus, Ancistrocladus [14••]. For the majority of these genera, subclasses Ia and Ib chitinase genes are present, although probable subclass Ib chitinases pseudogenes are also identified in Triphyophyllum and Ancistrocladus [14••]. The presence of these non-functional class I chitinases is thought to be due to detrimental domain rearrangement and/or excision events [47] that occurred during the transition from a full-time to either a part-time or completely non-carnivorous habit [14••]. Thus the degradation of the endogenous chitinase sequence is correlated with either a reduction or loss of functional carnivory in the Caryophyllales.

The utilization of chitinases for the carnivorous habit can be extended toother chitinase classes. Class IV chitinases have been identified from a proteome of Nepenthes alata closed or newly opened pitcher fluid [8], while class III chitinases have been demonstrated to be upregulated in the presence of preyin Nepenthes [15••]. In addition to class I, the presence of classes II and III chitinases have been confirmed in Drosera plants not exposed to prey [48], although it is unclear whether classes II and III are specifically involved in carnivory or expressed in tissues other than the glands [49]. In Dionaea, several chitinase transcripts were found to be in relatively high abundance under different conditions using two methods of transcriptome sequencing: 454 sequencing of RNA pooled from traps fed ants, a solution of coronatine, and stimulated with filter paper saturated with urea, chitin, or water (454); Illumina sequencing of RNA from traps stimulated with yellow meal-worm beetles (Illumina) [9••]. These transcripts correspond to subclass Ib (DM_TRA02_REP_contig53074 and NG-5590_Gland_-cleanedcontig 77527 (454); Locus_610_Transcript_2/ 2_Confidence_1.000 (Illumina)), class IV (DM_TRA02_-contig13240 and DM_TRA02_REP_contig60010 (454)), and class V chitinases (DM_TRA02_contig126504 (454)) based on amino acid sequence [50] and signatures available in the Pfam protein families database. In all studies described here, differences in the presence of certain chitinase classes could be attributed to whether prey was present in the trap at the time of collection, the method of stimulation, or type of sequencing platform.

The occurrence of multiple chitinase classes associated with carnivorous traps and digestive fluid may indicate synergistic roles in insect digestion, some of which could be influenced by differential expression patterns. Agro-bacterium-mediated RNA interference would likely be an effective method to study the roles of chitinases in digestion, as transformation has already been demonstrated in Drosera [51].

Molecular evolution of chitinases in the carnivorous Caryophyllales

Selection and subfunctionalization of class I chitinases

In non-carnivorous plants, there is evidence for the rapid and adaptive evolution of class I chitinases involved in pathogen response for both eudicots and monocots. In Arabis, amino acid replacements occur disproportionately in the active site cleft, the location in which hydrolysis of chitin polymers occurs [52]. Positively selected sites are also significantly overrepresented in the active site cleft of Poaceae class I chitinases, yet the majority of these sites are not shared with those identified in Arabis [53]. Instances of positive selection are thought to be the result of an evolutionary arms race between chitinolytic enzymes and competitive inhibitors produced by fungal pathogens [52,53]. Dissimilarities in the number and location of selected sites suggest lineage specific adaptations to selective pressures.

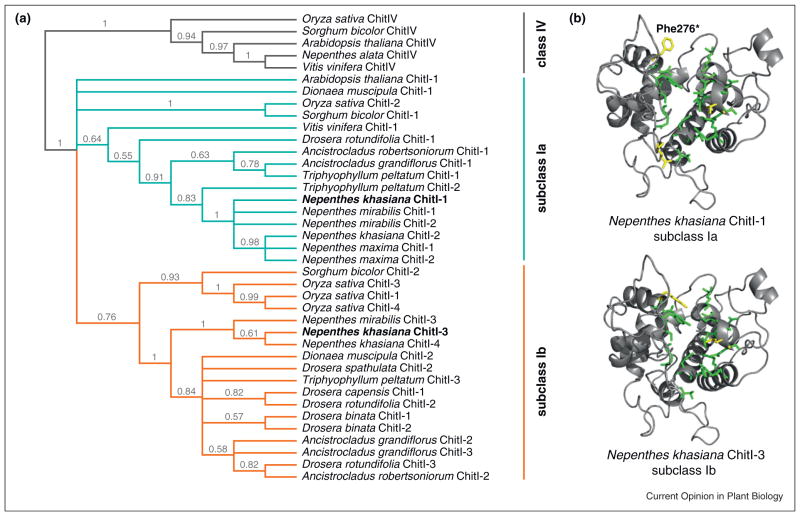

In the carnivorous Caryophyllales, functional divergence of class I chitinases is supported by the separation of subclasses Ia and Ib chitinases into distinct phylogenetic clades (Figure 2a), in addition to signatures of selection specific to each of the two subclasses (Figure 2b) [14••]. When comparing positively selected sites of carnivorous Caryophyllales class I chitinases with sites previously identified as targets of selection in Arabis and Zea, only five sites are shared, one of which is located within the active site cleft [14••]. Sites under positive selection in carnivorous plant class I chitinases may also result in substitutions that could affect structure and function.

Figure 2.

Molecular evolution of class I chitinases in the carnivorous Caryophyllales. (a) Phylogenetic reconstruction for subclasses Ia and Ib chitinases of the carnivorous plants of the Caryophyllales based on the Bayesian inference analyses for HMM-derived class I chitinases homologs, with posterior probabilities indicated at nodes on the 50% majority rule tree [14••]. Nepenthes khasiana chitinases in bold (Nepenthes khasiana ChitI-1 and Nepenthes khasiana ChitI-3) are homology modeled in (b). (b) Residues colored green or yellow within the three-dimensional models for subclass Ia Nepenthes khasiana ChitI-1 and subclass Ib Nepenthes khasiana ChitI-3 represent sites interacting with NAG. Yellow residues highlight differences between the two subclasses. Site 276 (asterisk) is identified as under positive selection in Nepenthes subclass Ia chitinases (Phe276). Models based on previous analyses of N. khasiana class I chitinase structures [14••].

In protein structure homology modeling of N. khasiana subclass Ia (N. khasiana ChitI-1) and Ib (N. khasiana ChitI-3) chitinases, it is evident that a substitution at a site under positive selection in Nepenthes subclass Ia chitinases (Phe276), could affect substrate binding, activity, and potentially functionality (Figure 2b) [14••]. This observation is supported by selective replacement studies In Arabidopsis and Zea at a site positionally homologous to Phe276 [14••,54–57]. It is therefore likely that differential selection is driving the process of sub-functionalization of class I chitinases in the carnivorous Caryophyllales, especially given that the absence of a CTE allows release of subclass Ib from digestive glands into the carnivorous traps, whereas subclass Ia remains localized to the vacuole and is involved in pathogenic response against fungi.

Evolutionary relationships among class III chitinases

Class III chitinases may be developmentally regulated, induced by abiotic stress, or upregulated in response to fungal pathogens similar to class I chitinases [58•]. In the carnivorous Caryophyllales, phylogenetic studies of class III chitinases have been limited to Nepenthes [15••]. Class III chitinase genes, were cloned from eight different species of Nepenthes and analyzed within a phylogenetic framework. Protein-specific divergence events were not particularly evident, with the resulting gene trees agreeing relatively well with a previously published species tree based on chloroplast sequence data [59], although with higher support. The Nepenthes class III chitinases were further characterized by studying expression within the pitcher, and interestingly, it was found that expression could be localized in closed as well as opened pitchers, in pitchers that were induced by Drosophila melanogaster, and in pitted glands and fluid, suggesting that these enzymes are broadly expressed and are utilized for pathogenic response in addition to plant carnivory [15••].

Conclusions

The carnivorous plants of the Caryophyllales use a number of specialized adaptations to trap and digest prey. A variety of sessile, stalked, or pitted glands associated with the carnivorous leaves allow for prey capture as well as excretion of enzymes and absorption of digested material, however, vasculature within these glands is not required for plant carnivory [16••]. Families sister to the carnivorous Caryophyllales exhibit similar gland morphologies, yet it is likely that stalked and pitted glands evolved independently in these lineages, separate from the evolution of stalked and pitted glands in the carnivores [16••]. In addition to sticky glands, waxes and superhydrophylic trichomes are located on carnivorous trap surfaces. These are also present on the leaves of non-carnivorous plants, functioning in the immobilization and slowing of herbivores, which may suggest that such basic structures have been modified in the evolution of carnivorous plants to function specifically in carnivory.

Digestive enzymes located within the carnivorous plant trap and functioning in carnivory may have been coopted from enzymes involved in plant defense from herbivory and fungal pathogens. Plant chitinases are known to function in response to pathogens [42,58•,60], and related chitinases are located within the carnivorous traps of the carnivorous Caryophyllales, have been found to be associated with digestive glands, and have been shown to be either induced in response to prey or are constitutively expressed [6–8,9••,15••]. Molecular evolutionary studies support subfunctionalization of class I chitinases, whereby subclass Ia is used for pathogenic response and subclass Ib for plant carnivory [14••]. This is in contrast to class III chitinases, which may have a more comprehensive role in the carnivorous Caryophyllales and is apparently a single gene with multiple functionalities [15••].

Further evolutionary studies, particularly investigations of molecular signatures of selection coupled with structure and function, are greatly warranted to determine if additional enzymes active within traps have been coopted for carnivory. Furthermore, studies of digestive enzymes, especially at the level of next-generation sequencing, have focused heavily on the carnivorous Caryophyllales, yet the carnivorous habit has evolved independently at least four additional times within the angiosperms in the orders Ericales, Lamiales, Oxalidales, and Poales [61]. Although some members of these groups (e.g. Sarracenia of Ericales), most likely do not endogenously produce the enzymes located within the traps [62•], other members such as Pinguicula (Lamiales), have been demonstrated to exude enzymes from their digestive glands [63]. A more thorough assessment of the digestive constituents at the genetic level would greatly add to our understanding of convergent evolution among the carnivorous plants.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a NSF Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant awarded to C.D.S. and T.R. (DEB 1011021). In addition, T.R. acknowledges support from NIH K12 GM000708 and C.D.S. acknowledges support from the Prytanean Alumni Association. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions and comments.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Hooker JD. Report to the British Association for the Advancement of Science: Report of the Forty-Fourth Meeting. Belfast: Department of Zoology and Botany; 1875. pp. 102–116. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lönnig WE, Becker HA. Carnivorous plants. Nat Encycl Life Sci. 2004 http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/npg.els.0003818.

- 3.Darwin CR. Insectivorous Plants. London: John Murray; 1875. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amagase S, Mayumi M, Nakayama S. Digestive enzymes in insectivorous plants. IV. Enzymatic digestion of insects by Nepenthes secretion and Drosera peltata extract: proteolytic and chitinolytic activities. J Biochem. 1972:72. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a129956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robins R, Juniper B. The secretory cycle of Dionaea muscipula Ellis. II. Storage and synthesis of the secretory proteins. New Phytol. 1980;86:297–311. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matusíková I, Salaj J, Moravcíková J, Mlynárová L, Nap JP, Libantová J. Tentacles of in vitro-grown round-leaf sundew (Drosera rotundifolia L. ) show induction of chitinase activity upon mimicking the presence of prey. Planta. 2005;222:1020–1027. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eilenberg H, Pnini-Cohen S, Schuster S, Movtchan A, Zilberstein A. Isolation and characterization of chitinase genes from pitchers of the carnivorous plant Nepenthes khasiana. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:2775–2784. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatano N, Hamada T. Proteome analysis of pitcher fluid of the carnivorous plant Nepenthes alata. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:809–816. doi: 10.1021/pr700566d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9••.Schulze WX, Sanggaard KW, Kreuzer I, Knudsen AD, Bemm F, Thøgersen IB, Bräutigam A, Thomsen LR, Schliesky S, Dyrlund TF, Escalante-Perez M, Becker D, Schultz J, Karring H, Weber A, Højrup P, Hendrich R, Enghild JJ. The protein composition of the digestive fluid from the venus flytrap shed light on prey digestion mechanisms. Mol Cell Proteom. 2012;11:1306–1319. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.021006. Using 454 and Illumina methods of next-generation sequencing, the authors characterize the major constituents of Dionaea muscipula digestive fluid. This is the first study to provide a thorough genetic basis for digesitve enzyme activity in Dionaea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amagase S. Digestive enzymes in insectivorous plants. III. Acid proteases in the genus Nepenthes and Drosera peltata. J Biochem. 1972;72:73–81. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a129899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dexheimer J. Study of mucilage secretion by the cells of the digestive glands of Drosera capensis L. using staining of the plasmalemma and mucilage by phosphotungstic acid. Cytologia (Tokyo) 1978;43:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry Y, Steer MW. Acid phosphatase localization in the digestive glands of Dionaea muscipula Ellis flytraps. J Histochem Cytochem. 1985;33:339–344. doi: 10.1177/33.4.3980983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrissey SM. Carbonic anhydrase and acid secretion in a tropical insectivorous plant (Nepenthes) Int Union Biochem. 1964;32:660. [Google Scholar]

- 14••.Renner T, Specht CD. Molecular evolution and functional evolution of class I chitinases for plant carnivory in the Caryophyllales. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:2971–2985. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss106. The authors provide the first molecular evolutionary study of class I chitinases utilized in plant carnivory within the most speciose group of carnivorous plants: the Caryophyllales. Differential selection observed and subfunctionalization proposed for subclasses Ia and Ib chitinases. Protein homology modeling is utilized to connect sites under selection with structure and function. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15••.Rottloff S, Stieber R, Maischak H, Turini FG, Heubl G, Mithöfer A. Functional characterization of a class III acid endochitinase from the traps of the carnivorous pitcher plant genus, Nepenthes. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:4639–4647. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err173. The authors present a study that combines a phyogenetic reconstruction for Nepenthes class III chitinases with gene expression data. Relationships among the class III chitinases support previous species phylogenies, but with better support. Expression data suggests that class III chitinases have a comprehensive role in pathogenic response and digestion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16••.Renner T, Specht CD. A sticky situation: assessing adaptations for plant carnivory in the Caryophyllales by means of stochastic character mapping. Int J Plant Sci. 2011;172:889–901. The most recent phylogenetic reconstruction for genera of the carnivorous Caryophyllales and related non-carnivorous plants is presented along with the evolution of characters associated with the carnivorous glands. Three strongly supported clades were identified: (1) Droseraceae, (2) Nepenthaceae, (3) members of Ancistrocladaceae, Dioncophyllaceae, and Drosophyllaceae. Within the multicellular glands, vasculature is not required for plant carnivory and the presence of sessile glands is the likely ancestral character state. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson J. The mucilage- and other glands of the Plumbagineae. Annu Bot. 1890;4:231–258. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colombo P, Trapani S. Morpho-anatomical observations on three Limonium species endemic to the Pelagic Islands. Flora Med. 1992;2:77–90. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakai WS. Scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive X-ray analysis of chalk secreting leaf glands of Plumbago capensis. Am J Bot. 1974;61:94–99. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lüttge U. Structure and function of plant glands. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1971;22:23–44. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faraday CD, Thomson WW. Functional aspects of the salt glands of the Plumbaginaceae. J Exp Bot. 1986;37:1129–1135. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fahn A, Werker E. In: Anatomical mechanisms of seed dispersal. Kozlowski TT, editor. Academic Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrero V, de Vega C, Stafford GI, Staden JV, Johnson SD. Heterostyly and pollinators in Plumbago auriculata (Plumbaginaceae) S Afr J Bot. 2009;75:778–784. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoltzfus A, Suda J, Kettering R, Wolfe A, Williams S. Secretion of digestive enzymes in Plumbago. The 4th International Carnivorous Plant Conference; Tokyo, Japan. 2002. pp. 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson B. Adaptations to foliar absorption of faeces: a pathway in plant carnivory. Ann Bot. 2005;95:757–761. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellis AG, Midgley JJ. A new plant-animal mutualism involving a plant with sticky leaves and a resident hemipteran insect. Oecologia. 1996;106:478–481. doi: 10.1007/BF00329705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zangirólame Gonçalves A, Mercier H, Mazzafera P, Quevedo Romero G. Spider-fed bromeliads: seasonal and interspecific variation in plant performance. Ann Bot. 2011;107:1047–1055. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcr047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Givnish TJ, Burkhardt EL, Happel RE, Weintraub JD. Carnivory in the bromeliad Brocchinia reducta, with a cost/benefit model for the general restriction of carnivorous plants to sunny, moist, nutrient-poor habitats. Am Nat. 1984;124:479–497. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whitney HM, Federle W. Biomechanics of plant–insect interactions. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2013;16:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30••.Bauer U, Di Giusto B, Skepper J, Grafe TU, Federle W. With a flick of the lid: a novel trapping mechanism in Nepenthes gracilis pitcher plants. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038951. The authors describe the trapping mechanism for Nepenthes gracilis which is a unique, semi-slippery wax crystal surface on the underside of the pitcher lid that used the impact of rain drops to ‘flick’ prey into the trap. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31••.Bauer U, Clemente CJ, Renner T, Federle W. Form follows function: morphological diversification and alternative trapping strategies in a carnivorous plant genus. J Evol Biol. 2012;25:90–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02406.x. A comparative study of Nepenthes trap morphologies involved in creating slippery surfaces for capturing prey. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaume L, Perret P, Gorb E, Gorb S, Labat J-J, Rowe N. How do plant waxes cause flies to slide? Experimental tests of wax-based trapping mechanisms in three pitfall carnivorous plants. Arthopod Struct Dev. 2004;33:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33•.Bauer U, Scharmann M, Skepper J, Federle W. ‘Insect aquaplaning’ on a superhydrophilic hairy surface: how Heliamphora nutans Benth. pitcher plans capture prey. Proc R Soc Lond B: Biol Sci. 2013;280:20122569. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2569. The authors describe the specialized surface morphology of Heliamphora pitchers used to capture prey. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Legrand M, Kauffmann S, Geoffroy P, Fritig B. Biological function of pathogensis-related proteins: four tobacco pathogenisis-related proteins are chitinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:6750–6754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brogue K, Chet I, Holliday M, Cressman R, Biddle P, Knowlton S, Mauvais CJ, Broglie R. Transgenic plants with enhanced resistance to the fungal pathogen Rhizoctonia solani. Science. 1988;254:1194–1197. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5035.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samac D, Hironaka C, Yallaly P, Shah D. Isolation and characterization of the genes encoding basic and acidic chitinase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1990;93:907–914. doi: 10.1104/pp.93.3.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Majeau N, Trudel J, Asselin A. Diversity of cucumber chitinase isoforms and characterization of one seed basic chitinase with lysozyme activity. Plant Sci. 1990;68:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham L, Sticklen M. Plant chitinases. Can J Bot. 1994;72:1057–1083. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heitz T, Segond S, Kauffmann S, Geoffroy P, Prasad V, Brunner F, Fritig B, Legrand M. Molecular characterization of a novel tobacco pathogenesis-related (PR) protein: a new plant chitinase/lysozyme. Mol Genet Genom. 1994;245:246–254. doi: 10.1007/BF00283273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neuhaus JM, Sticher L, Meins F, Boller T. A short C-terminal sequence is necessary and sufficient for the targeting of chitinases to the plant vacuole. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10362–10366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neuhaus JM, Pietrzak M, Boiler T. Mutation analysis of the C-terminal vacuolar targeting peptide of tobacco chitinase: low specificity of the sorting system, and gradual transition between intracellular retention and secretion into the extracellular space. Plant J. 1994;5:45–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.5010045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlumbaum A, Mauch F, Vögeli U, Boller T. Plant chitinases are potent inhibitors of fungal growth. Nature. 1986;324:365–367. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leah R, et al. Biochemical and molecular characterization of three barley seed proteins with antifungal properties. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1564–1573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jach C, et al. Enhanced quantitative resistance against fungal disease by combinatorial expression of different barley antifungal proteins in transgenic tobacco. Plant J. 1995;8:97–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.08010097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robins RJ, Juniper BE. The secretory cycle of Dionaea muscipula Ellis. IV. The enzymology of the secretion. New Phytol. 1980;84:401–412. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rottloff S, Müller U, Kilper R, Mithöfer A. Micropreparation of single secretory glands from the carnivorous plant Nepenthes. Anal Biochem. 2009;349:135–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shinshi H, Neuhaus JM, Ryals J, Meins F. Structure of a tobacco endochitinase gene: evidence that different chitinase genes can arise by transposition of sequences encoding a cysteine-rich domain. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;14:357–368. doi: 10.1007/BF00028772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matusíková I, Libantová J, Moravcíková J, Mlynárová L, Nap J-P. The insectivorous sundew (Drosera rotundifolia L. ) might be a novel source of PR genes for biotechnology. Biologia (Bratislava) 2004;59:719–725. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Libantová J, Kämäräinen T, Moravcíková J, Matusíková I, Salaj J. Detection of chitinolytic enzymes with different substrate specificity in tissues of intact sundew (Drosera rotundifolia L.) Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:851–856. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9254-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Passarinho P, de Vries SC. Arabidopsis Chitinases: A Genomic Survey. The Arabidopsis Book; 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirsikorpi M, Kämäräinen T, Teeri T, Hohtola A. Agrobacterium-mediated transcormation of round leaved sundew (Drosera rotundifolia L.) Plant Sci. 2002;162:537–542. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bishop JG, Dean AM, Mitchell-Olds T. Rapid evolution in plant chitinase: molecular targets of selection in plant pathogen coevolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5322–5327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tiffen P. Comparative evolutionary histories of chitinase genes in the genus Zea and family Poaceae. Genetics. 2004;167:1331–1340. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.026856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verburg JG, Rangwala SH, Samac DA, Luckow VA, Huynh QK. Examination of the role of tyrosine-174 in the catalytic mechanism of the Arabidopsis thaliana chitinase: comparison of variant chitinases generated by site-directed mutagenesis and expressed in insect cells using baculovirus vectors. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:223–230. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verburg JG, Smith CE, Lisek CA, Huynk QK. Identification of an essential tyrosine residue in the catalytic site of chitinase isolated from Zea mays that is selectively modified during inactivation with 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3886–3893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anderson MD, Jensen A, Robertus JD, Leah R, Skriver K. Heterologous expression and characterization of wild-type and mutant forms of a 26 kDa endochitinase from barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Biochem J. 1997;322:815–822. doi: 10.1042/bj3220815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang CM, Chye M, Ramalingam S, Ouyang S, Zhao K, Ubhayasekera W, Mowbray SL. Functional analyses of the chitin-binding domains and the catalytic domain of Brassica juncea chitinase BjCHI1. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;56:285–298. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-3382-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58•.Grover A. Plant chitinases: genetic diversity and physiological roles. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2012;31:57–73. The authors describe the specialized surface morphology of Heliamphora pitchers used to capture prey. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meimberg H, Wistuba A, Dittrich P, Heubl G. Molecular phylogeny of Nepenthaceae based on cladistic analysis of plastid trnK intron sequence data. Plant Biol. 2001;3:164–175. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verburg JG, Huynh QK. Purification and characterization of an antifungal chitinase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1991;95:450–455. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.2.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.APGII: An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II. Bot J Linn Soc. 2003;14:399–436. [Google Scholar]

- 62•.Glenn A, Bodri MS. Fungal endophyte diversity in Sarracenia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032980. The authors give a detailed account of the diversity of beneficial fungi within Sarracenia pitchers. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heslop-Harrison Y, Heslop-Harrison J. The digestive glands of Pinguicula: structure and cytochemistry. Annu Bot. 1981;47:293–319. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Juniper BE, Robins RJ, Joel DM. The Carnivorous Plants. London, UK: Academic Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]