Abstract

Basal-type triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC) are aggressive and difficult to treat relative to luminal type breast cancers. TNBC often express abundant Met receptors and are enriched for transcriptional targets regulated by hypoxia inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α), which independently predicts cancer relapse and increased risk of metastasis. Brk/PTK6 is a critical downstream effector of Met signaling and required for HGF-induced cell migration. Herein, we examined the regulation of Brk by HIFs in TNBC in vitro and in vivo. Brk mRNA and protein levels are upregulated strongly in vitro by hypoxia, low glucose and reactive oxygen species. In HIF-silenced cells, Brk expression relied upon both HIF-1α and HIF-2α, which we found to regulate BRK transcription directly. HIF-1α/2α silencing in MDA-MB-231 cells diminished xenograft growth and Brk re-expression reversed this effect. These findings were pursued in vivo by crossing WAP-Brk (FVB) transgenic mice into the METmut knock-in (FVB) model. In this setting, Brk expression augmented METmut-induced mammary tumor formation and metastasis. Unexpectedly, tumors arising in either METmut or WAP-Brk X METmut mice expressed abundant levels of Sik, the mouse homolog of Brk, which conferred increased tumor formation and decreased survival. Taken together, our results identify HIF-1α/2α as novel regulators of Brk expression and suggest that Brk is a key mediator of hypoxia-induced breast cancer progression. Targeting Brk expression or activity may provide an effective means to block the progression of aggressive breast cancers.

Introduction

Breast tumor kinase (Brk), also known as PTK6, is a soluble protein tyrosine kinase typically expressed in differentiated epithelial cells of the skin and gastrointestinal tract (1). While Brk is not found in normal mammary tissue, it is aberrantly expressed in up to 86% of breast tumors, with the highest levels in advanced tumors (2–4). Other cancers, such as melanoma, lymphoma, ovarian, prostate and colon cancer also exhibit overexpressed and/or mislocalized Brk (reviewed in (5)).

Brk contains N-terminal src homology 2 (SH2), src homology 3 (SH3) and C-terminal kinase domains. It is distantly related to Src family kinases, as they share 56% homology within the kinase domain (6). Brk lacks a myristoylation site, and is present in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Many Brk substrates, both cytoplasmic and nuclear, have important functions in cancer, including signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) molecules, Akt, and Sam68 (reviewed in (5)). Brk is activated downstream of ErbB family receptors and Met receptors and is required for EGF-, heregulin-, and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-enhanced cell migration (7–9). Although Brk and ErbB2 have distinct gene loci, they are coamplified in some breast cancers (10). Brk expression in ErbB2-induced tumors correlates with shorter latency and resistance to the ErbB2 inhibitor, Lapatinib (10). Moreover, elevation of Brk expression in breast cancer cells confers resistance to the EGFR-blocking antibody, cetuximab, by inhibiting EGFR degradation (11). Brk also mediates anchorage-independent growth in breast cancer cells through modulation of the IGF receptor (12). While significant advancements have been made toward understanding the mechanisms of Brk signaling (5), little is known about the regulation of Brk expression in breast cancers.

Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) are the principal mediators of transcriptional responses to cellular hypoxia (13). Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF-1 and HIF-2) are heterodimers of two oxygen-regulated subunits, HIF-1α or HIF-2α and HIF-1β. HIF-1β is constitutively expressed, whereas HIFα subunits are continually degraded through the ubiquitin pathway under normal oxygen tensions (normoxia). In response to hypoxia, HIFα subunits are stabilized and translocate to the nucleus, where they heterodimerize with HIF-1β. HIF transcription factors recognize a core hypoxia-response elements (HREs) within enhancer regions of target genes (14, 15), and act as master regulators of many cellular functions relevant to cancer progression, including angiogenesis, glucose metabolism, and tumor growth and metastasis (13). Indeed, HIF-1α is overexpressed in many human cancers (reviewed in (16)), and over-expression in breast tumors predicts relapse and indicates a higher risk of metastasis (17). HIF-1α levels are significantly higher in invasive and poorly differentiated breast cancers as compared to well-differentiated cancers (18–20). Specifically, increased levels of HIF-1α mRNA and the core hypoxic transcriptional response are associated with hormone receptor negative breast cancers (19, 21).

Breast tumors lacking estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and HER2, termed triple negative breast cancers (TNBC), are typically more aggressive relative to ER/PR/HER2 positive tumors. TNBCs largely fall into the basal and claudin-low molecular subtypes and have a worse prognosis relative to luminal breast cancers (reviewed in (22)), in part, because these patients are not candidates for targeted therapies that block ER and HER2. TNBC patients are treated with systemic chemotherapies that include cytoskeletal- or DNA-damaging agents, which can be effective, but fail to specifically target the unknown and presumably diverse molecular drivers of cancer metastasis. As Brk is aberrantly expressed in both luminal and TNBC subtypes, but is not found in the normal mammary tissue, it is an attractive candidate for selective targeting of invasive breast cancer cells.

Herein, we examined the mechanism of Brk induction in breast cancer, with focus on TNBC/basal-type breast cancers abundantly expressing both Met and HIF target genes. We hypothesized that Brk, a known mediator of Met signaling and stress activated kinase pathways, is upregulated in response to cellular hypoxia, thereby promoting cancer cell survival, cell motility, and metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

MDA-MB-231 cell lines were cultured in DMEM (HyClone Thermo Scientific) without pyruvate supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Invitrogen) and 1% pen/strep. Stable knock-down of HIF1A, HIF2A or both genes in MDA-MB-231 cells was generated by transduction as previously described (see Supplemental Methods) (20). MDA-MB-231 shMock, shHIF1A, and shHIF2A cells were supplemented with 4µg/mL puromycin, and shHIF1A/2A cells were supplemented with 8µg/mL puromycin, and 2mg/mL hygromycin and authenticated 4/11/13 by SoftGenetics LLC or DDC Medical and results compared to the ATCC STR database. Cells were maintained in 5% CO2 at 21% O2 (normoxia, ambient air) or at 1–2% O2 (hypoxia).

Cell proliferation assay

Proliferation was measured via MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]- 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay as previously described (23). MDA-MB-231 cells were plated at 2.5 × 103 cells per well in 24-well plates.

Protein extraction

Patient-derived xenograft tissue fragments maintained by the HCI breast tumor bank resource (24) were obtained (Supplementary Table 1). High-salt enriched whole cell lysates (HS-WCE) were prepared from HCI tumors or MDA-MB-231 tumors as previously described (25). Whole cell lysates from cultured cells were isolated as described in (26). Additional human tumor specimens were obtained from the University of Minnesota Biological Materials Procurement Network (BioNet) and histologically subtyped and processed for protein expression as previously reported (23).

Immunoblotting

Proteins were resolved on 7.5% SDS-PAGE or 3–8% Tris-Acetate gels, transferred to PVDF membrane and probed with primary antibodies: HIF-1α (Novus Biologicals, NB100–134 or NB-100–479), HIF-2α (Novus Biologicals, NB100–122), p38 (Cell Signaling, 9212), Vinculin (Sigma, V9131), Actin (Sigma, A4700), Brk (Santa Cruz, sc-1188), Sik (Santa Cruz, sc-916) or β-Tubulin (AbCam, 6046). Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (Bio-Rad or Santa Cruz) were visualized with SuperSignal West Pico or Millipore ECL substrate. Representative images of triplicate experiments are shown. Densitometry was performed via ImageJ analysis and normalized to the loading control.

qPCR

qPCR assays were performed as previously described (26). Briefly, cells were plated at 2.5 × 105 cells/well in 6 well plates and cultured at normoxia for 32hrs, then transferred to hypoxia (1% O2) for 24 hrs or left at normoxia. Target gene expression was normalized to the expression of internal control, TATA-binding protein (TBP).

ChIP Assays

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as previously described (26). Briefly, MDA-MB-231 cells were plated at a density of 3 × 106 cells per 15cm cell culture dish and cultured at normoxia for 32 hrs, then cultured at normoxia or 1% O2 for 24 hrs. Lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) overnight (18 hrs) with 2 µg of HIF-1α antibody, HIF-2α, and RNA polymerase II (Covance, 8WG16) or an equal amount of rabbit IgG. Negative control rabbit IgG was immunoprecipitated from MDA-MB-231 cultured at hypoxia for 24 hours.

Transgenic mice and generation of tumors in NOD/scid/gamma recipients

MMTV-PyMT+ HIF-1 wildtype (WT) and knockout (KO) mammary tumors were generated as described in (25). WAP-Brk transgenic mice (4) and Met mutant knock-in mice were generated as described (27), monitored daily for tumor development and euthanized when tumor volume approached 1 cm3. Cultured MDA-MB-231 cells were dissociated into single cells and diluted 1:1 (vol:vol) with growth-factor reduced Matrigel-Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) at 250,000 cells per 10 µl. Cells were injected into the right inguinal mammary fat pad of 3–6-week old female NOD/scid/ILR2γ (NSG) recipients. Recipients were palpated up to two times per week, and tumor volumes were calculated by caliper measurement as described previously (28). At experimental endpoint, tumor wet weight was also measured.

Immunostaining

Immunohistochemistry of HIF-1 WT and KO mammary formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor sections was performed as previously described (4). Briefly, tissues were incubated 1 hour at room temperature with serum-free protein block (Dako X0909), then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary anti-Sik antibody (1:1000 in Dako Antibody Diluent (S0809)) and developed by DAB peroxidase staining. For immunofluorescence staining, FFPE sections (5–7 um) were antigen retrieved using 1× citrate buffer, stained with Sik primary antibody (sc - 916) at 1:50 dilution overnight at room temperature, followed by Alexa Flour-594 (Invitrogen) secondary and mounted with VECTASHIELD (Vector Laboratories, Inc. Burlingame, CA).

Kaplan-Meier curves

Survival analysis was done using the van’t Veer microarray dataset downloaded from Rosetta Inpharmatics (http://www.rii.com/publications/2002/vantveer.html). Normalized Brk expression values were divided into four quartiles: 75 tumors with high Brk expression (>0.074) and 76 tumors with lowest Brk (<−0.036) expression. The y-axis (probability) is defined as the frequency of survival. Data were analyzed using the survival package within WinSTAT® for Excel.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as means +/− SEM. Statistical significance for qPCR assays was determined using unpaired Student’s t-tests. Tumor xenograft growth significance over time was determined via two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. Tumor latency was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier methodology and curves compared using the Mantel-Cox Log-rank test. Brk mRNA levels were assessed using the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data.

Results

Brk is upregulated in response to hypoxia and cellular stress

Numerous studies have demonstrated Brk overexpression in breast and other cancers relative to normal control tissues (5). Data from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) were analyzed via Oncomine to compare the levels of Brk mRNA expression in a large number of high quality samples representing both invasive ductal and invasive lobular breast cancer versus normal breast tissues. Interestingly, independent of tumor subtype, Brk expression was significantly increased in both invasive ductal carcinoma (p=1.50E−35) and invasive lobular carcinoma (p=3.35E−10), relative to normal breast tissue samples (Fig. 1A). To investigate Brk expression levels specifically in basal/TNBCs, we collected a panel of TNBC cell lines and tumors. Human tumor samples were histologically scored and processed as previously described (23). We observed a range of Brk expression by Western blot in cell lines and tumor samples (Fig. 1B). Additionally, Brk expression was assayed in a subset of previously described (24) xenografted tumors maintained in the Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI) breast tumor tissue bank. All HCI TNBC and luminal B (HER2+) subtype xenografts exhibited high levels of Brk protein expression relative to luminal B (Her2−) tumors (Fig. 1C; Supplementary Table 1). In addition, both HIF-1α and HIF-2α proteins were highly enriched in the TNBC samples relative to HER2 or steroid hormone receptor positive tumors. These data confirm that Brk, HIF-1α and HIF-2α are co-expressed in human breast carcinomas, particularly in TNBCs.

Figure 1. Brk is upregulated in breast cancers and in human TNBC cell lines.

A. Brk mRNA levels (via TCGA) comparing normal breast tissue to invasive ductal carcinomas (IDC), and to invasive lobular carcinomas (ILC). B. Western blot analysis of Brk protein levels in TNBC cell lines the (MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, DKAT, HCC1937, and HS587T) and in triple negative human tumor specimens with antibodies to Brk and p38 (loading control). C. Human breast cancer xenograft fragments derived from the HCI resource were obtained at generation 3–5. HS-WCE (10 µg/lane) were subjected to Western blot analysis for Brk, HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and β-tubulin (loading control).

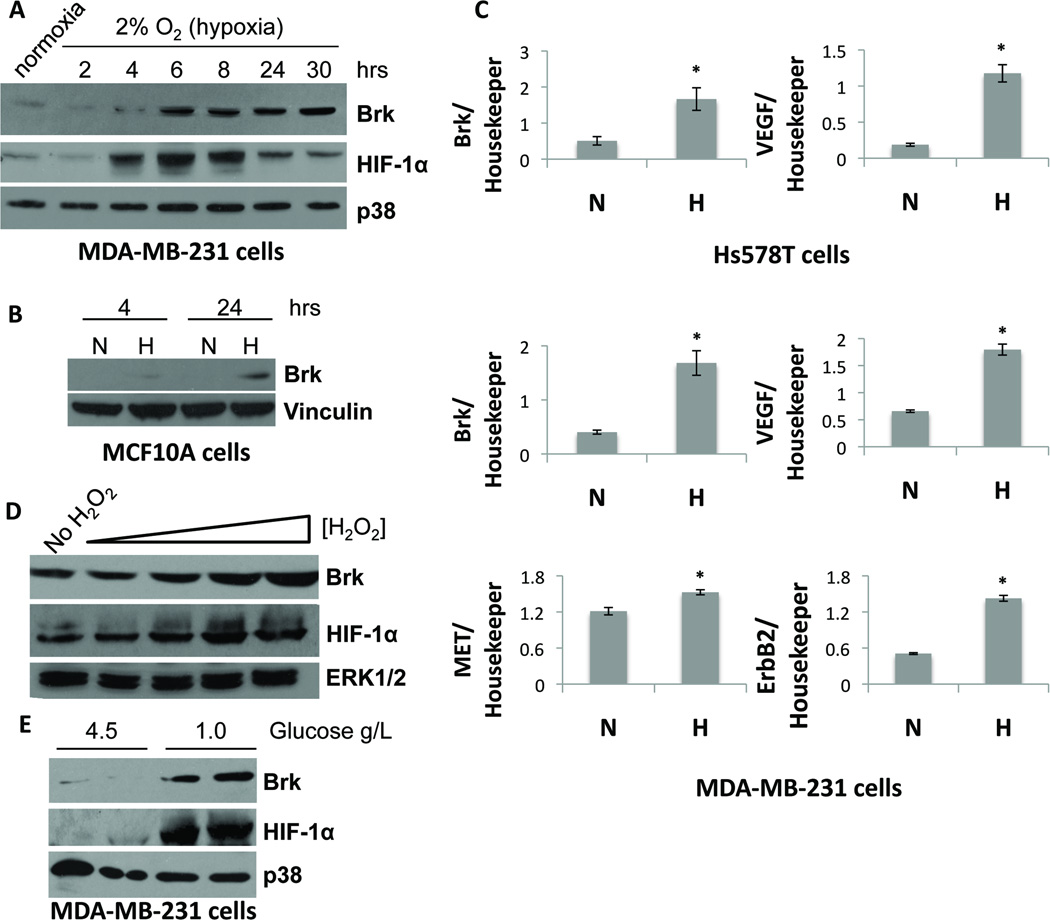

Multiple mechanisms of Brk upregulation exist (10, 29). We hypothesized that Brk expression may also be induced upon cellular stress. TNBC cells were exposed to various stresses, including hypoxia, and examined Brk protein and mRNA expression. MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were subjected to mild hypoxic conditions (2% O2) and harvested for Western blot analysis. HIF-1α protein was upregulated following exposure of MDA-MB-231 cells to low oxygen for 4–30 hours relative to cells incubated in normoxic conditions (Fig. 2A). HIF-1α protein levels peaked at approximately 6 hours of hypoxia, followed by decreased but sustained expression out to 30 hours. Interestingly, Brk levels increased at 6 hours of hypoxia compared to normoxic controls, coinciding with the peak of HIF-1α protein expression. Elevated Brk protein levels were maintained out to 30 hours. The same experiment was performed in non-tumorigenic immortalized MCF10A cells, previously reported to be Brk-null (30) (Fig. 2B), as well as ER+/PR+ MCF7 (Supp. Fig. 1A) and T47D breast cancer cells (data not shown). Following 24 hours of hypoxia exposure, Brk levels were consistently increased in all cell lines.

Figure 2. Hypoxia and other cellular stresses induce Brk expression.

A. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in normoxia or 2% O2 (hypoxia) for the indicated times and subjected to Western blot analysis for Brk or p38 (loading control). B. MCF10A cells were cultured in normoxia or 2% O2 (hypoxia) for 4 or 24 hours. Whole-cell lysates were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels and probed with antibodies to Brk or vinculin (loading control). C. Hs578T and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured at normoxia or hypoxia for 24 hours and then mRNA levels were analyzed by qPCR after normalization to TBP expression. Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance (p <0.05; an unpaired Student’s t test). D. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 0, 1, 10, 50 or 100 µM H2O2. Lysates were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels and probed for antibodies specific for Brk, HIF-1α, and p38 (loading control). E. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in media with either 4.5g/L (DMEM-Hi) or 1.0 g/L (DMEM-Lo) glucose. Duplicate samples (independent lysates) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with antibodies to Brk, HIF-1α and p38 (loading control).

To assess the transcriptional regulation of Brk during hypoxia, we cultured Hs578T and MDA-MB-231 cells for 24 hours in 1% O2 and examined Brk mRNA levels by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). Brk transcript levels increased significantly at hypoxia compared to normoxia, in both TNBC cell lines (Fig. 2C). Levels of VEGF, a known HIF-1 target gene, also significantly increased in both cells lines. Interestingly, transcript levels of ERBB2 and Met receptor (MET), growth factor receptors known to activate Brk signaling, were also increased significantly by hypoxia in MDA-MB-231 cells. Similar results were observed in MCF7 breast cancer cells (Supp. Fig. 1B).

The above results suggest that Brk induction may be characteristic of more universal responses to cellular stresses that also input to HIF-1α (31). We therefore assessed the levels of Brk expression in response to increasing concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by treatment with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and following glucose deprivation. When MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to H2O2 (0–100 µM), Brk and HIF-1α protein levels were induced or stabilized, respectively, in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2D). A similar response occurred when cells were exposed to media containing lowered glucose (1g/L) as compared to base DMEM-Hi media (4.5g/L) (Fig 2E). These data, indicating Brk induction by multiple cell stress pathways, suggest a mechanism for coordinate regulation of downstream signaling in response to HIF activation.

Brk is a novel, direct HIF transcriptional target gene

The Brk promoter contains multiple potential hypoxia response elements (HREs) within 20 kb of the transcriptional start site (TSS) (Fig. 3A). To examine HIF-α recruitment these regions, we performed chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays with MDA-MB-231 cells cultured at normoxia or hypoxia for 24 hours. We observed that HIF-1α and HIF-2α were robustly recruited to HRE 1 located 1.5 kb upstream of the Brk TSS at hypoxia compared to normoxia (Fig. 3B). As a functional correlate of transcriptional activity associated with this HRE, we assessed the recruitment of RNA polymerase II to this region (HRE 1) and observed robust recruitment of this enzyme following exposure to hypoxia (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that HIF-containing transcriptional complexes present at HRE 1 in hypoxia are active. Essentially identical results (i.e. hypoxia-regulated recruitment of HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and Pol II) were obtained for HREs 2–5 (Supp. Fig. 2). HIF-1α recruitment to the VEGF promoter (Fig. 3C) was included as a positive control (32). The first intron in the transcriptionally inactive hemoglobin B (HBB) gene (33) served as a negative control (Fig. 3D). These data, strongly implicate HIFs in upregulation of Brk mRNA under conditions of cellular stress in MDA-MB-231 cells.

Figure 3. Brk is a direct HIF target gene.

A. Schematic representation of HREs in the proximal Brk promoter that were assessed for HIF-1α/2α recruitment. B. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured at normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2) for 24 hours. ChIP assays with HIF-1α, HIF-2α or RNA pol II antibodies and qPCR were performed on the isolated DNA to determine HIF and pol II recruitment to HRE 1. Negative control isotype matched IgG controls were performed on MDA-MB-231 cells cultured at hypoxia for 24 hours. ChIP for HIF-1 was performed for the VEGF promoter (C), or the negative control HBB intron (D). Representative examples from triplicate experiments are shown.

To determine if HIF−1α was required for the induction of Brk in aggressive, metastatic mammary tumors, we first examined the expression of Sik, the mouse homologue of Brk, in end-stage HIF-1 wildtype (WT) or knockout (KO) mouse mammary tumors initiated by expression of the mouse mammary virus-driven polyoma middle T oncoprotein (MMTV-PyMT) transgene, as previously described (25). Colorimetric immunohistochemistry staining for Sik revealed a substantial loss of Sik protein expression in HIF-1 KO mammary tumors relative to WT tumors (Fig. 4A). These results were confirmed by immunofluorescence staining for Sik (red) and DAPI-nuclear staining (blue) (Fig. 4B). Sik was localized in the tumor epithelium and stroma. A no primary-antibody control demonstrated that immunoreactivity was entirely due to the primary Sik antibody (Fig. 4A); the specificity of Sik antisera was shown previously (34). Additionally, four HIF-1 WT and four HIF-1 KO PyMT tumors were assessed for Sik protein levels by Western blotting. We observed a marked reduction in Sik protein in HIF-1 KO tumors relative to HIF-1 WT tumors (Fig. 4C). Therefore, HIF-1α is required for robust expression of Sik in PyMT-mouse mammary tumors.

Figure 4. Sik protein in PyMT+ murine mammary tumors is dependent upon HIF-1α expression.

A. Immunohistochemistry of paraffin embedded sections from WT or HIF KO tumors stained for Sik or secondary antibody only (No 1-Ab) and developed with conventional DAB. B. Immunofluorescence images of HIF-1 WT or KO tumors derived from the MMTV-PyMT transgenic model. Paraffin embedded tissue sections were probed for Sik (detected with AlexaFluor-594, red) and stained with DAPI (blue). A no primary antibody control was run and showed no detectable staining (data not shown). C. Protein lysate from four HIF WT or HIF KO tumors were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with antibodies for HIF-1α, Sik, and vinculin as a loading control. A light and dark exposure of the HIF-1α blot are shown. Relative expression, via densitometry, is listed beneath.

Despite dramatic reduction in HIF-1 KO PyMT-tumors, Sik protein was still weakly detected (Fig. 4). Notably, HIF-1α and HIF-2α have overlapping transcriptional targets (20, 35–37). Therefore, we tested the dependence of Brk expression on HIFα molecules in human breast cancer cells cultured under hypoxic conditions. MDA-MB-231 cells expressing empty vector (shControl), HIF1A shRNA, HIF2A shRNA, or both HIF1A and HIF2A shRNAs (DKD) were cultured at normoxia or 1% O2 for 6 or 24 hours. As expected, HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein levels were increased at 6 and 24 hours in shControl cells cultured at hypoxia; target gene expression was greatly reduced in hypoxic shHIF1A and shHIF2A cells (Fig. 5A). We observed a substantial hypoxia-induced increase in HIF-2α protein expression in cells expressing shHIF1A relative to shControls. The up-regulation of HIF-2α in response to efficient HIF1A knockdown was previously shown in MCF-7 cells (20). Importantly, only double-knock down (DKD) cells completely lacked both HIF molecules (Fig. 5A). Brk mRNA was significantly decreased in MDA-MB-231 cells expressing either shHIF1A or shHIF2A relative to shControl cells, but significantly induced by hypoxia relative to normoxia (Fig. 5B). However, when both HIF1A and HIF2A were simultaneously knocked down, we observed an almost complete ablation of Brk transcript and protein expression (Fig. 5B inset). Similar results were observed in MCF7 cells (Supp. Fig. 1C). These data suggest that when expression of either HIF-1α or HIF-2α is lost, the other HIFα subunit may compensate to induce Brk expression, consistent with the regulation of numerous other HIF-target genes (20).

Figure 5. Brk mRNA and protein expression are ablated upon loss of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α.

A. MDA-MB-231 cells expressing shControl, shHIF1A, shHIF2A, or DKD were cultured at normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2) for 6 or 24 hours. Lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies to HIF-1α or HIF-2α, or β-Tubulin (loading control). The asterisk indicates a cross-reactive band and the arrow indicates HIF-2α. B. MDA-MB-231 cells expressing shControl, shHIF1A, shHIF2A, or DKD were cultured at normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2) for 24 hours. Protein and mRNA were isolated and mRNA was analyzed by qPCR after normalization to TBP. Inset: Western blotting analysis for Brk and ERK1/2 (loading control).

Ectopic Brk expression enhances growth of HIF1A/HIF2A knockout tumors in vivo

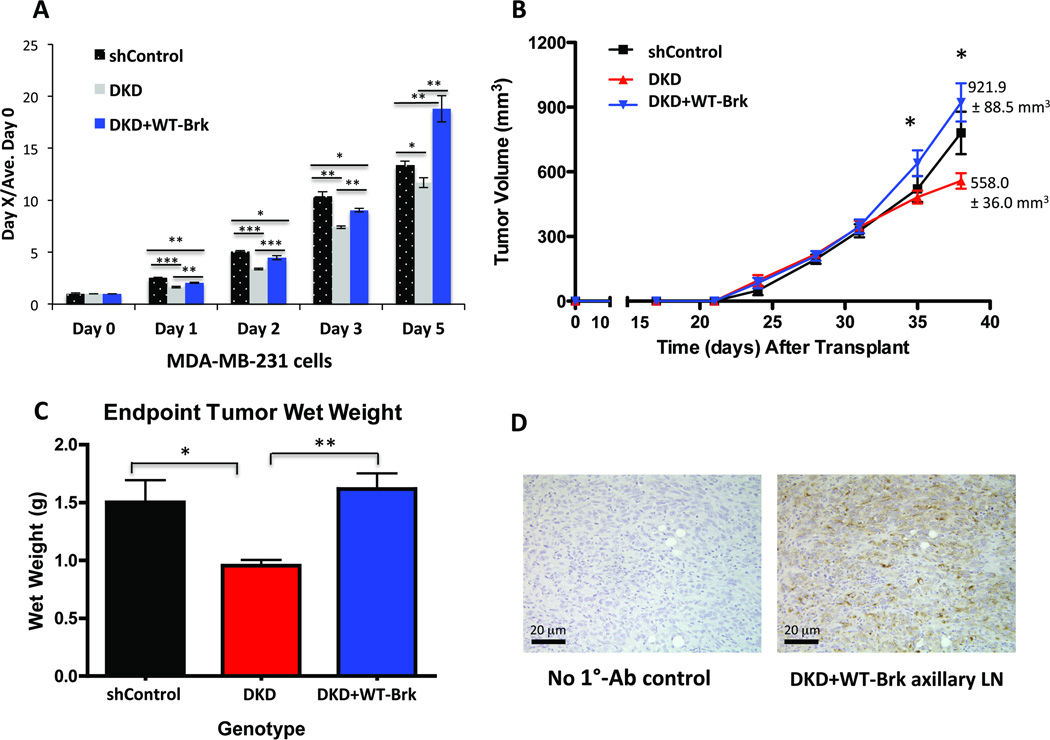

Previous studies showed that tumors derived from MDA-MB-231 cells that lack HIF-1α and HIF-2α displayed significantly decreased growth relative to wildtype controls (38–40). As Brk knockdown in breast cancer cells has been shown to inhibit proliferation and block cell migration in vitro (5) as well as decrease xenograft tumor size in vivo (41), we sought to determine if Brk overexpression could compensate for decreased tumor growth caused by loss of HIF-1 and HIF-2 activity (i.e. a model where endogenous Brk is not HIF-induced). Thus, MDA-MB-231 DKD cells were retrovirally infected with a pFB-neo-WT-Brk overexpression construct. Western blot analysis confirmed that knockdown of HIF1A and HIF2A was maintained in DKD cells (Supp. Fig. 3A), and the cells were thus unable to induce endogenous Brk (Supp. Fig. 3B). In contrast, DKD cells engineered to over-express wildtype BRK exhibited constitutive Brk expression, as expected (Supp. Fig. 3B). Consistent with previously published in vivo results (38–40), DKD cells grew significantly less than shControl cells via in vitro MTT assays. This growth defect was recovered (days 1–3) and then surpassed (day 5) upon re-expression of WT-Brk (Fig. 6A). These cells (shControl, DKD and DKD + Brk) were used to establish orthotopic mammary tumors in NOD scid gamma female recipients (n=9 mice/cohort). Xenografts were palpated and tumor growth was measured with digital calipers as previously described (28). In agreement with previous reports (38–40), knockdown of both HIF1A and HIF2A significantly decreased breast cancer cell growth in vivo relative to shControl cells at day 38; 780.6 ± 98.4 mm3 vs. 558.0 ± 36.0 mm3, respectively (Fig. 6B–C). Surprisingly, DKD cells constitutively expressing exogenous Brk (DKD + Brk) exhibited robust in vivo xenograft growth that not only reversed the HIF DKD growth phenotype (p <0.05 at day 35 and p<0.001 at day 38; day 38 mean tumor volume 921.9 ± 88.5 mm3 vs. 558.0 ± 36.0 mm3, respectively), but exceeded that of shControl tumors at day 38 post-transplant (Fig. 6B, 921.9 ± 88.5 mm3 vs. 780.6 ± 98.4 mm3, respectively; p<0.05). These data indicate that constitutive Brk expression is sufficient to recover the diminished growth phenotype of HIF DKD cells. In addition, comparison of mean ex vivo tumor mass confirmed that the shControl xenograft tumors were significantly larger than DKD tumors (Fig. 6C, p = 0.05). Similarly, DKD + Brk xenograft tumors were significantly larger than DKD tumors as determined by comparison of tumor wet weight (p<0.01). Western blotting of end-stage tumors confirmed the maintenance of HIF knockdown over the experimental time course (data not shown).

Figure 6. Brk promotes growth in HIF DKD cells in vitro and in vivo.

A. MTT cellular proliferation assays were performed with MDA-MB-231 cells cultured at 1% O2 for the indicated amounts of time. B. Mammary fat pad xenografts were established with either shControl, DKD or DKD + Brk MDA-MB-231 cells (n=9 mice /cohort). Mean tumor volume per cohort was plotted over time; asterisks indicate significant differences via two-way ANOVA between DKD and DKD+ Brk tumors at both day 35 and day 38 post-transplant (p <0.05, p<0.001). Mean tumor volumes at day 38 for DKD and DKD + Brk cohorts are listed. C. Mean ex vivo tumor wet weight (* p< 0.05, ** p<0.01, ANOVA). D. Representative histological images depicting CAM5.2 positive axillary lymph nodes (LN) from mice with DKD+Brk xenograft tumors. An image from a no primary antibody control is also shown (No 1°-Ab control).

These results were independently repeated wherein axillary regions were necropsied to detect the presence of lymph node lesions. We observed that 40% of the mice transplanted with DKD + BRK xenograft tumors harbored lymph node macrometastases (2/5 mice), with node masses greater than 2 mm in diameter, while no mice bearing DKD or shControl xenograft tumors exhibited overt node involvement by necropsy or H&E analysis (0/5 mice per genotype). The presence of human breast cancer cells in these lymph nodes was confirmed by staining for human-specific anti-cytokeratin, CAM5.2, as in (24)(Fig 6D). These data suggest that in vivo, Brk is a major driver of breast cancer phenotypes that are typically associated with HIF-1α/2α mediated tumor progression and metastasis.

Brk increases the appearance of basal-like mammary tumors in METmut mice

Our recent work demonstrated that Brk signals downstream of Met receptors to increase HGF-driven malignant processes in vitro (8). High Met receptor levels are also strongly correlated with TNBC and basal-like breast cancers (27). Therefore, we sought to determine the effects of Brk-dependent signaling on mammary tumor development in a well-characterized mouse model of human breast cancer. To generate mammary tumors, WAP-Brk (FVB) transgenic mice were crossed with METMut knock-in (FVB) mice, which express a constitutively active Met receptor and mimic the pathological features of human basal-like breast cancer (4, 27). As the Met receptor is known to be an upstream activator of Brk, mammary epithelial cells derived from WAP-Brk × METMut mice are predicted to have constitutive activation of Brk (7, 8).

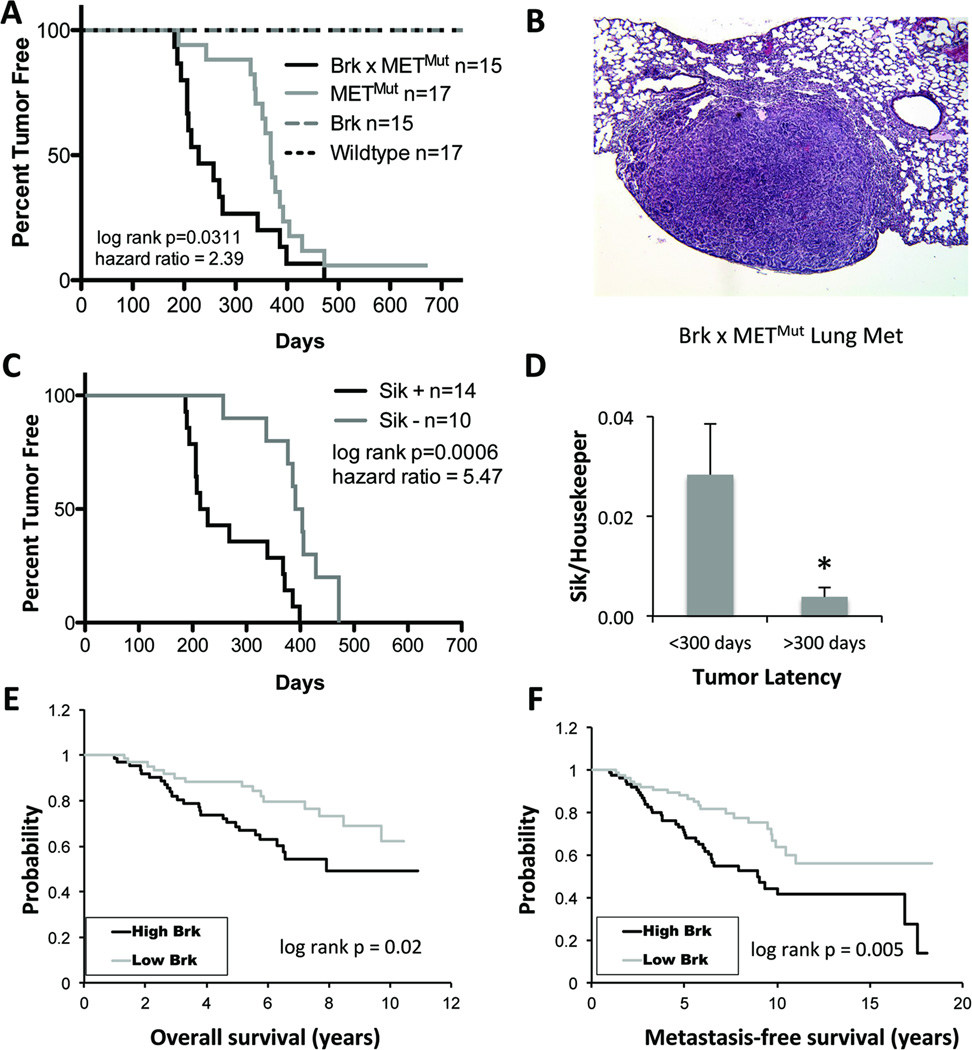

Following continuous pregnancies (n=3) to activate mammary gland specific WAP-driven Brk transgene expression, groups of age-matched, multiparous female mice (n=17 mice per cohort; Wildtype, Brk alone, METmut alone, or Brk × METMut) were monitored for tumor formation weekly and sacrificed once tumors grew to a volume of approximately 1 cm3. Mice in the wildtype and WAP-Brk (i.e. non-activated Brk) cohorts failed to develop mammary tumors over the experimental time course (Fig. 7A). As predicted (27), nearly 100% of METmut mice developed mammary tumors (by day 700). However, increased tumor formation and decreased overall tumor-free survival were observed in WAP-Brk × METMut mice relative to METMut mice (log-rank p=0.03, Fig. 7A). The median survival of WAP-Brk × METMut mice was 228 days, whereas median survival of METMut was 368 days. We collected tissues (lung, liver, brain, ovaries) from mice upon necropsy for analysis of potential (latent) metastatic events (Table 1). Importantly, Brk × METMut mice developed more (20%) metastases relative to METMut mice (12%) (Fig. 7B, Table 1). Notably, metastases were observed in mice that survived (i.e. were not euthanized due to primary tumor size) at least 275 days; of these, 3/6 (50%) Brk × METMut mice developed distant metastases, while 2/15 (13%) METMut mice developed distant metastases. Taken together, these data suggest that Brk activation in the mammary epithelium, whether driven by hypoxia or constitutive MET expression, is a driver of rapid tumor progression in vivo.

Figure 7. Growth of basal-like mammary tumors that originate in METmut mice is accelerated by expression of the Brk transgene or endogenous Sik.

A. Percent tumor-free survival of METMut mice compared to Brk × METMut transgenic mice by Kaplan-Meier analysis and significance determined by Mantel-Cox Log-rank test (hazard ratio, 2.39; 95% CI = 1.082 to 5.276). B. Representative hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained section from a Brk × METMut mouse lung harboring metastases. C. Percent tumor-free survival, stratified by endogenous Sik expression status. Significance was determined with Mantel-Cox Log-rank test (hazard ratio, 5.47; 95% CI = 2.060 to 14.50). D. Tumors were harvested from end-stage METMut or WAP-Brk × METMut mice, and mean expression of Sik mRNA was analyzed by qPCR after normalization to TBP. Early tumors were classified as those that developed by 300 days and latent tumors were classified as those that developed after 300 days (* p<0.05). E & F. Kaplan-Meier curves were derived from data analyzed from 117 primary human breast tumor specimens (42) for overall survival (E.) and metastasis-free survival (F.), stratified by high (top quartile, >75%) and low (lower quartile, <25%) Brk expression. Significance was determined by Mantel-Cox Log-rank test.

Table 1. Enhanced metastasis in Brk × METMut mice relative to METMut and WAP-Brk mice.

Organs with distant metastases were sectioned and H&E stained. Number of animals harboring distant metastases were quantified and are listed.

| Genotype | # of Mets/ Genotype/Site |

Total # of Mice with Mets |

Total # of Mice with Mets post day 275 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Ovary | |||

| WT | 0 | 0 | 0/15 (0%) | 0/15 (0%) |

| Brk | 0 | 0 | 0/17(0%) | 0/17(0%) |

| METMut | 2 | 0 | 2/17 (12%) | 2/15 (13%) |

| Brk × METMut | 3 | 1 | 3/15 (20%)#+ | 3/6 (50%)* |

= 1 mouse had multiple organs with distant metastases

p= 0.26 (chi squared)

p= 0.02 (chi squared)

Most solid tumors are hypoxic. Our in vitro studies related to hypoxia regulation of Brk expression (Figs 2–3) suggested that endogenous Sik expression may be induced during the course of tumor progression in METmut mice. Therefore, all tumors extracted from mice were screened for Sik mRNA expression via qPCR. Notably, when data were stratified by Sik expression alone, regardless of Brk transgene genotype, there was a strong association between Sik positivity and decreased tumor-free survival (log-rank p=0.0006) (Fig. 7C). Mice with Sik-positive tumors had a median survival of 221 days, whereas mice with Sik-negative tumors had a median survival of 397.5 days. Overall, the decreased latency correlated with significantly higher levels of Sik in tumors (Fig. 7C–D), suggesting that Sik expression accelerates tumor development and progression.

To further support these findings as relevant to human tumors, we stratified 117 primary human breast tumor samples according to Brk mRNA expression (42). High Brk expression correlated significantly with both decreased overall survival (Fig. 7E) and decreased metastasis-free survival (Fig. 7F). These data suggest that the WAP-Brk × METMut mice model human disease with high Brk expression. These mice may provide a useful model system for pre-clinical testing of novel therapies that may include Brk inhibitors.

DISCUSSION

Although an improved understanding of Brk signaling in breast cancer is emerging (5, 7–9), knowledge of the mechanisms by which Brk is aberrantly expressed in the majority of breast cancers remains incomplete. We have identified cellular microenvironmental stressors, including hypoxia, to be major cues that result in increased Brk expression in both normal and neoplastic mammary epithelial cells. We have additionally shown through ChIP assays and gene expression analysis that this mechanism of Brk transcriptional regulation is HIF-dependent. This finding is particularly relevant to breast cancer subtypes that exhibit high constitutive expression of HIFα subunits, specifically, TNBCs (Fig. 1) and inflammatory breast cancers (19, 21). Importantly, forced expression of Brk in cells lacking both HIF-1α and HIF-2α increased xenograft growth in vivo and promoted lymph node metastasis, suggesting that Brk is a key mediator of the hypoxia-induced metastasis program. Furthermore, using a mouse model of Brk overexpression (WAP-Brk × METMut knock-in), we demonstrated that activated Brk signaling drives mammary tumor initiation and rapid tumor growth in vivo. Tumor growth is further accelerated in the presence of activated endogenous Sik (the mouse homologue of Brk, which is not expressed in the normal mammary gland). Sik expression is tightly linked to rapid tumor onset and shortened survival, regardless of Brk transgene genotype. The impact of activated Brk signaling on metastatic progression is of particular interest, as 20% of the Brk × METMut mice developed distant metastases, compared to only 12% of the METMut mice. Clearly, high Brk expression in primary human breast tumors is significantly correlated with decreased overall survival as well as decreased metastasis-free survival (Fig. 7E–F). Further studies, designed specifically to assess differences in metastases (i.e. following removal of primary tumors and/or using larger cohorts (43)), are needed to better define the details of how Brk signaling contributes to the stepwise process of metastasis.

Our data suggest that Brk can be up-regulated during hypoxia by either HIF-1 or HIF-2 (Fig. 5). Numerous studies have determined that HIF-1α and HIF-2α regulate several of the same genes (20, 35, 36), as expected since the core binding sequence (RCGTG) is recognized by both HIF-1 and HIF-2 (37, 44). Indeed, significant levels of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α have been observed to bind to almost all of the HIF binding sites identified by ChIP genome wide. However, functional analysis of the role of individual HREs in the regulation of Brk expression by HIFs is outside the scope of this study. Genome-wide studies have also shown that, despite sharing the same response element, each HIFα subunit also differentially regulates a unique core of distinct genes (37). These studies highlight the complexity of HIF gene regulation and the possibility that HIF-1α and HIF-2α may be involved in both cooperative and compensatory gene regulation that is highly context-dependent (20), and underscore the need for further study. Molecular compensation (i.e. of one HIF for another) is an important consideration for targeting HIF-specific actions in the clinic.

Solid tumors experience widespread cell stress that acts as a form of selection pressure. Our previous studies have elucidated downstream mediators of Brk signaling that include stress-activated protein kinases (p38 MAPK and ERK5) and their substrates MEF2 and Sam68 (7–9). Intriguingly, in hTERT-RPE1 cells, HIF-1 transcriptional activity was enhanced by ERK5, and numerous hypoxia-regulated and HIF-1α target genes were specifically regulated by ERK5 (45). These results suggest that HGF, Met, Brk, ERK5, and HIF-1α may function together as a “feed-forward” autocrine signaling loop in response to hypoxia, ultimately resulting in high levels of Brk expression and adaptation to cell stress that enables cancer cells to migrate away from hypoxic regions to more hospitable microenvironments at distant sites. Related to this process is the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), a quintessential step that precedes carcinoma cell metastasis (46). HIF-1 is known to mediate EMT in breast tumors (25) and knock-down of Brk in MCF7 breast cancer cells partially reverses EMT, as measured by a decrease in mesenchymal markers (fibronectin and N-cadherin) and an increase in epithelial markers (E-cadherin and β-catenin) (47). Taken together, these studies suggest that increased Brk expression allows breast cancer cells to successfully migrate, in part via modulation of EMT-associated molecules. Importantly, Brk may act as a convergence point downstream of diverse growth factor receptors that are frequently overexpressed in breast cancer. Targeting Brk (in addition to MET and/or HIF-dependent signaling) as part of combination breast cancer treatment strategies may more effectively subvert HIF-driven processes that contribute to aggressive tumor progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. George F. Vande Woude for kindly providing the METmut mice and Dr. Alana L. Welm for providing patient xenograft fragments that were serially passaged in mice. We also thank Dr. Luciana P. Schwab for expert assistance with surgery and animal care. This work was supported by NIH R01 CA107547 to C.A.L.) and NIH R01 CA138488 (T.N.S.), the Department of Defense W81XWH-09-1-0374 (T.N.S and D.L.P.) and the Swiss National Science Foundation grant 31003A_129962 (to R.H.W.). Dr. Hoogewijs is supported by the Forschungskredit of the University of Zürich and the Sassella Stiftung.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Vasioukhin V, Serfas MS, Siyanova EY, Polonskaia M, Costigan VJ, Liu B, et al. A novel intracellular epithelial cell tyrosine kinase is expressed in the skin and gastrointestinal tract. Oncogene. 1995;10:349–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Born M, Quintanilla-Fend L, Braselmann H, Reich U, Richter M, Hutzler P, et al. Simultaneous over-expression of the Her2/neu and PTK6 tyrosine kinases in archival invasive ductal breast carcinomas. The Journal of pathology. 2005;205:592–596. doi: 10.1002/path.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell PJ, Barker KT, Martindale JE, Kamalati T, Lowe PN, Page MJ, et al. Cloning and characterisation of cDNAs encoding a novel non-receptor tyrosine kinase, brk, expressed in human breast tumours. Oncogene. 1994;9:2383–2390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lofgren KA, Ostrander JH, Housa D, Hubbard GK, Locatelli A, Bliss RL, et al. Mammary gland specific expression of Brk/PTK6 promotes delayed involution and tumor formation associated with activation of p38 MAPK. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2011;13:R89. doi: 10.1186/bcr2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostrander JH, Daniel AR, Lange CA. Brk/PTK6 signaling in normal and cancer cell models. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2010;10:662–669. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serfas MS, Tyner AL. Brk, Srm, Frk, Src42A form a distinct family of intracellular Src-like tyrosine kinases. Oncology research. 2003;13:409–419. doi: 10.3727/096504003108748438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostrander JH, Daniel AR, Lofgren K, Kleer CG, Lange CA. Breast tumor kinase (protein tyrosine kinase 6) regulates heregulin-induced activation of ERK5 and p38 MAP kinases in breast cancer cells. Cancer research. 2007;67:4199–4209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castro NE, Lange CA. Breast tumor kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 mediate Met receptor signaling to cell migration in breast cancer cells. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2010;12:R60. doi: 10.1186/bcr2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Locatelli A, Lofgren KA, Daniel AR, Castro NE, Lange CA. Mechanisms of HGF/Met signaling to Brk and Sam68 in breast cancer progression. Hormones & cancer. 2012;3:14–25. doi: 10.1007/s12672-011-0097-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiang B, Chatti K, Qiu H, Lakshmi B, Krasnitz A, Hicks J, et al. Brk is coamplified with ErbB2 to promote proliferation in breast cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:12463–12468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805009105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Lu Y, Liang K, Hsu JM, Albarracin C, Mills GB, et al. Brk/PTK6 sustains activated EGFR signaling through inhibiting EGFR degradation and transactivating EGFR. Oncogene. 2012;31:4372–4383. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irie HY, Shrestha Y, Selfors LM, Frye F, Iida N, Wang Z, et al. PTK6 regulates IGF-1-induced anchorage-independent survival. PloS one. 2010;5:e11729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wenger RH, Hoogewijs D. Regulated oxygen sensing by protein hydroxylation in renal erythropoietin-producing cells. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2010;298:F1287–F1296. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00736.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenger RH, Stiehl DP, Camenisch G. Integration of oxygen signaling at the consensus HRE. Science's STKE: signal transduction knowledge environment. 2005;2005:re12. doi: 10.1126/stke.3062005re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semenza GL. Defining the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer biology and therapeutics. Oncogene. 2010;29:625–634. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dales JP, Garcia S, Meunier-Carpentier S, Andrac-Meyer L, Haddad O, Lavaut MN, et al. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor HIF-1alpha predicts early relapse in breast cancer: retrospective study in a series of 745 patients. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2005;116:734–739. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bos R, van der Groep P, Greijer AE, Shvarts A, Meijer S, Pinedo HM, et al. Levels of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha independently predict prognosis in patients with lymph node negative breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:1573–1581. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto Y, Ibusuki M, Okumura Y, Kawasoe T, Kai K, Iyama K, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha is closely linked to an aggressive phenotype in breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2008;110:465–475. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9742-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stiehl DP, Bordoli MR, Abreu-Rodriguez I, Wollenick K, Schraml P, Gradin K, et al. Non-canonical HIF-2alpha function drives autonomous breast cancer cell growth via an AREG-EGFR/ErbB4 autocrine loop. Oncogene. 2012;31:2283–2297. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gatza ML, Kung HN, Blackwell KL, Dewhirst MW, Marks JR, Chi JT. Analysis of tumor environmental response and oncogenic pathway activation identifies distinct basal and luminal features in HER2-related breast tumor subtypes. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2011;13:R62. doi: 10.1186/bcr2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podo F, Buydens LM, Degani H, Hilhorst R, Klipp E, Gribbestad IS, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: present challenges and new perspectives. Molecular oncology. 2010;4:209–229. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knutson TP, Daniel AR, Fan D, Silverstein KA, Covington KR, Fuqua SA, et al. Phosphorylated and sumoylation-deficient progesterone receptors drive proliferative gene signatures during breast cancer progression. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2012;14:R95. doi: 10.1186/bcr3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeRose YS, Wang G, Lin YC, Bernard PS, Buys SS, Ebbert MT, et al. Tumor grafts derived from women with breast cancer authentically reflect tumor pathology, growth, metastasis and disease outcomes. Nature medicine. 2011;17:1514–1520. doi: 10.1038/nm.2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwab LP, Peacock DL, Majumdar D, Ingels JF, Jensen LC, Smith KD, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha promotes primary tumor growth and tumor-initiating cell activity in breast cancer. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2012;14:R6. doi: 10.1186/bcr3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagan CR, Regan TM, Dressing GE, Lange CA. ck2-dependent phosphorylation of progesterone receptors (PR) on Ser81 regulates PR-B isoform-specific target gene expression in breast cancer cells. Molecular and cellular biology. 2011;31:2439–2452. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01246-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graveel CR, DeGroot JD, Su Y, Koeman J, Dykema K, Leung S, et al. Met induces diverse mammary carcinomas in mice and is associated with human basal breast cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:12909–12914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810403106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao D, Corle C, Seagroves TN, Johnson RS. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha is a key regulator of metastasis in a transgenic model of cancer initiation and progression. Cancer research. 2007;67:563–572. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang SA, Lee ST. PTK6 promotes degradation of c-Cbl through PTK6-mediated phosphorylation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2013;431:734–739. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamalati T, Jolin HE, Mitchell PJ, Barker KT, Jackson LE, Dean CJ, et al. Brk, a breast tumor-derived non-receptor protein-tyrosine kinase, sensitizes mammary epithelial cells to epidermal growth factor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:30956–30963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pouyssegur J, Dayan F, Mazure NM. Hypoxia signalling in cancer and approaches to enforce tumour regression. Nature. 2006;441:437–443. doi: 10.1038/nature04871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwon TG, Zhao X, Yang Q, Li Y, Ge C, Zhao G, et al. Physical and functional interactions between Runx2 and HIF-1alpha induce vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2011;112:3582–3593. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlesinger Y, Straussman R, Keshet I, Farkash S, Hecht M, Zimmerman J, et al. Polycomb-mediated methylation on Lys27 of histone H3 pre-marks genes for de novo methylation in cancer. Nature genetics. 2007;39:232–236. doi: 10.1038/ng1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Llor X, Serfas MS, Bie W, Vasioukhin V, Polonskaia M, Derry J, et al. BRK/Sik expression in the gastrointestinal tract and in colon tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 1999;5:1767–1777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu CJ, Wang LY, Chodosh LA, Keith B, Simon MC. Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in hypoxic gene regulation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2003;23:9361–9374. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9361-9374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raval RR, Lau KW, Tran MG, Sowter HM, Mandriota SJ, Li JL, et al. Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:5675–5686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5675-5686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schodel J, Oikonomopoulos S, Ragoussis J, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Mole DR. High-resolution genome-wide mapping of HIF-binding sites by ChIP-seq. Blood. 2011;117:e207–e217. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-314427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schito L, Rey S, Tafani M, Zhang H, Wong CC, Russo A, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-dependent expression of platelet-derived growth factor B promotes lymphatic metastasis of hypoxic breast cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:E2707–E2716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214019109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong CC, Gilkes DM, Zhang H, Chen J, Wei H, Chaturvedi P, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a master regulator of breast cancer metastatic niche formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:16369–16374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113483108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H, Wong CC, Wei H, Gilkes DM, Korangath P, Chaturvedi P, et al. HIF-1-dependent expression of angiopoietin-like 4 and L1CAM mediates vascular metastasis of hypoxic breast cancer cells to the lungs. Oncogene. 2012;31:1757–1770. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Ludyga N, Anastasov N, Rosemann M, Seiler J, Lohmann N, Braselmann H, et al. Effects of simultaneous knockdown of HER2 and PTK6 on malignancy and tumor progression in human breast cancer cells. Molecular cancer research: MCR. 2013 doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van 't Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–536. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khanna C, Hunter K. Modeling metastasis in vivo. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:513–523. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xia X, Kung AL. Preferential binding of HIF-1 to transcriptionally active loci determines cell-type specific response to hypoxia. Genome biology. 2009;10:R113. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-10-r113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schweppe RE, Cheung TH, Ahn NG. Global gene expression analysis of ERK5 and ERK1/2 signaling reveals a role for HIF-1 in ERK5-mediated responses. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:20993–21003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ai M, Liang K, Lu Y, Qiu S, Fan Z. Brk/PTK6 cooperates with HER2 and Src in regulating breast cancer cell survival and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cancer biology & therapy. 2013;14 doi: 10.4161/cbt.23295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.