Background: Articular chondrocytes are responsible for producing articular cartilage and do not normally enter into terminal differentiation.

Results: Conditional knock-out of ESET histone methyltransferase results in hypertrophy, apoptosis, and terminal differentiation of articular chondrocytes.

Conclusion: ESET is essential for the normal maintenance of articular cartilage and joint function in adult animals.

Significance: Learning regulatory mechanisms of articular chondrocytes is critical to the understanding of joint diseases.

Keywords: Arthritis, Articular cartilage, Cartilage biology, Chondrocytes, Differentiation, Epigenetics, Gene Knockout, Histone methylation

Abstract

The exact molecular mechanisms governing articular chondrocytes remain unknown in skeletal biology. In this study, we have found that ESET (an ERG-associated protein with a SET domain, also called SETDB1) histone methyltransferase is expressed in articular cartilage. To test whether ESET regulates articular chondrocytes, we carried out mesenchyme-specific deletion of the ESET gene in mice. ESET knock-out did not affect generation of articular chondrocytes during embryonic development. Two weeks after birth, there was minimal qualitative difference at the knee joints between wild-type and ESET knock-out animals. At 1 month, ectopic hypertrophy, proliferation, and apoptosis of articular chondrocytes were seen in the articular cartilage of ESET-null animals. At 3 months, additional signs of terminal differentiation such as increased alkaline phosphatase activity and an elevated level of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 were found in ESET-null cartilage. Staining for type II collagen and proteoglycan revealed that cartilage degeneration became progressively worse from 2 weeks to 12 months at the knee joints of ESET knock-out mutants. Analysis of over 14 pairs of age- and sex-matched wild-type and knock-out mice indicated that the articular chondrocyte phenotype in ESET-null mutants is 100% penetrant. Our results demonstrate that expression of ESET plays an essential role in the maintenance of articular cartilage by preventing articular chondrocytes from terminal differentiation and may have implications in joint diseases such as osteoarthritis.

Introduction

Articular cartilage lines the joint and makes low friction and painless movement possible throughout life. Articular cartilage consists of a sparse population of articular chondrocytes that are responsible for the synthesis of an extracellular matrix consisting of collagens, proteoglycans, and noncollagenous proteins. Failure of articular chondrocytes to maintain the integrity of articular cartilage and/or to repair its damage is a common feature in joint diseases such as osteoarthritis.

All chondrocytes are derived from mesenchymal stem cells during skeletogenesis and joint formation and invariably follow two separate developmental paths; growth plate chondrocytes first appear during embryonic development and display a transient phenotype characterized by rapid proliferation and terminal differentiation, whereas articular chondrocytes are found only at the joint, are slow in cellular turnover, and are phenotypically stable. One possible mechanism for the development of osteoarthritis is the failure of articular chondrocytes to maintain their latent phenotype. In such a model, articular chondrocytes become mitotically active, proliferate, and express proteins such as type-X collagen, alkaline phosphatase, and matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13),3 proteins that are indicative of chondrocyte terminal differentiation. This is a process reminiscent of growth plate chondrocytes during endochondral ossification (1, 2). It should be pointed out, however, that osteoarthritis-like changes in joints may also occur without evidence of chondrocyte hypertrophy but instead are caused by inflammatory insults, increases in metabolic stress, and reactive oxygen species or, merely the accumulated effects of cell death (3, 4).

At the present time, a major unanswered question in skeletal development is the regulatory differences between articular and growth plate chondrocytes. Although certain regulatory factors of growth plate chondrocytes are also found in articular chondrocytes, it is not clear whether a common mechanism exists to control these two distinct chondrocyte populations.

We recently demonstrated that overexpression of the ESET histone methyltransferase protein (together with histone deacetylase HDAC4) leads to repression of Runx2-mediated gene transcription, that the endogenous ESET protein level is transiently up-regulated in prehypertrophic chondrocytes within the growth plate to function as a “gate keeper” in allowing entry into terminal differentiation, and that ESET knock-out in mesenchymal cells results in premature hypertrophy of growth plate chondrocytes during skeletal development (5). To investigate whether ESET is also essential for the maintenance of articular chondrocytes phenotype, in this study, we have evaluated the knee joints of more than 14 pairs of age- and sex-matched wild-type and ESET-null mice at different time points after birth. Here we report that ESET protein is expressed in articular chondrocytes and that mesenchyme-specific deletion of the ESET gene is associated with ectopic hypertrophy of articular chondrocytes, degeneration of articular cartilage, and other overt signs of terminal differentiation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Conditional ESET-null Mice

All animal studies were carried out in the C57BL/6 genetic background. Mating between ESET(exons 15&16)Flox/WT and ESET(exons 15&16)Flox/WT;Prx1-Cre gave rise to offspring with various genotypes at the expected Mendelian ratio. Newborn pups were kept at five or fewer per litter (by removing the healthy littermates) to increase survival of the knock-out mutants. Weaned mutant mice were fed with normal diet plus soft maintenance DietGel to ensure adequate intake of food and water. Identification of the floxed ESET allele and the Prx1-Cre transgene in the genome was confirmed by PCR as described previously (5). Prior to the study, all experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, WA.

Histology and Alkaline Phosphatase Assay

After fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde and decalcification in 14% EDTA, tissues were embedded in OCT compound and cut as 16-μm coronal sections. The sections were stained with the modified Harris hematoxylin solution (Sigma catalog number HHS32) plus eosin Y-phloxine B solution, or with a Safranin O stain kit from IHC World. To assay for alkaline phosphatase activity, tissues were treated with a previously published fixing solution (6). After fixation, tissues were cut, and the sections were incubated overnight in 1% magnesium chloride and then stained using an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining kit (Sigma, catalog number 86R-1KT). The stained sections were washed in water and dehydrated sequentially in ethanol and xylene before mounting for visualization.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Paraformaldehyde-fixed and decalcified tissue sections were used for detection of specific proteins at the knee joint. A rabbit polyclonal anti-ESET (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog number SC-66884) was used at 1:50 dilution. A rabbit polyclonal anti-ERG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog number SC-353) was used at 1:50 dilution. A rabbit polyclonal anti-PCNA (Abcam, catalog number ab2426) was used at 1:200 dilution. A rabbit polyclonal anti-active caspase 3 (Abcam, catalog number ab13847) was used at 1:100 dilution. A rabbit polyclonal anti-type II collagen (Rockland Immunochemicals Inc., catalog number 600-401-104) was used at 1:200 dilution after antigen retrieval through 0.2 m boric acid, pH 7.0 (overnight at 60 °C) followed by 2 mg/ml hyaluronidase (room temperature, 30 min). A rabbit polyclonal anti-type X collagen (5) was used at 1:100 dilution following treatment with 2 mg/ml hyaluronidase. A rabbit polyclonal anti-MMP13 (Abcam, catalog number ab39012) was used at 1:100 dilution after 1 h of antigen retrieval with 20 μg/ml proteinase K at room temperature. A rabbit polyclonal anti-matrilin-1 (LifeSpan BioSciences, catalog number LS-B5000) was used at 1:200 dilution after antigen retrieval at 98 °C in 0.01 m sodium citrate, pH 6.0, for 20 min followed by 2 mg/ml hyaluronidase treatment. Following overnight incubation with the primary antibodies, tissue sections were incubated with Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, 1:200 dilution) at 4 °C for 1 h. After washes with 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS, sections were mounted with VECTASHIELD medium containing DAPI for examination under a fluorescence microscope.

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) Assay

Detection of apoptotic cells at the knee joints was carried out using the DeadEndTM fluorometric TUNEL system from Promega. In brief, the knee joint sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, rinsed in PBS, and treated with proteinase K (20 μg/ml) in PBS at room temperature for 15 min to make cells permeable. After a second fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde and repeated washes in PBS, incorporation of fluorescein-12-dUTP into the DNA ends by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase was done at 37 °C for 60 min. The reaction was then stopped by immersing the slides in 2× SSC buffer. The tissue sections were washed in PBS and counterstained in DAPI mounting medium for examination under a fluorescence microscope. Fluorescein-12-dUTP labeling results in localized green fluorescence within the nuclei of apoptotic cells only.

RESULTS

ESET Is Expressed in Articular Chondrocytes

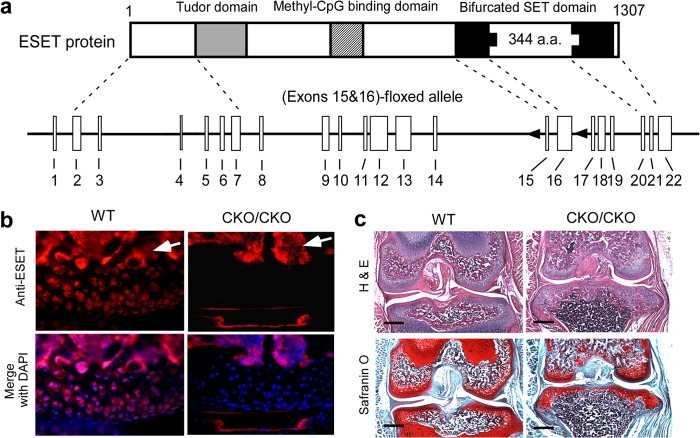

The ESET protein is encoded by a single copy gene that is evolutionarily conserved. The mouse ESET gene is 36 kb in length and consists of 22 exons, giving rise to a full-length ESET protein with 1307 amino acids (7). To achieve mesenchyme-specific knock-out of ESET utilizing an allele in which exons 15 and 16 are flanked by two loxP sites (Fig. 1a), we utilized Prx1-Cre mice as the deleter strain because the paired-related homeobox gene-1 (Prx1) limb enhancer can drive mesenchyme-specific Cre expression that first appears in the forelimb mesenchyme at day E9.5 followed by appearance of Cre activity in the hind limb bud the next day at E10.5 (8). Prx1-Cre mice showed a pattern of normal skeletal development (including the joint) similar to wild-type animals in ages up to 2 years. Mating of ESET(exons 15&16)Flox/WT;Prx1-Cre mice with ESET(exons 15&16)Flox/WT mice produced viable ESET(exons 15&16)Flox/Flox;Prx1-Cre pups, referred to as (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO, that were slightly smaller than wild-type littermates but easily recognized due to their characteristically shortened forelimbs (5). These (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mutant mice can live for more than 1 year without obvious defects in other organ systems, thus enabling us to investigate the effects of ESET knock-out on articular chondrocytes.

FIGURE 1.

ESET genomic structure and expression in articular chondrocytes. a, diagrams of ESET protein domains and the floxed ESET allele. a. a., amino acids. b, ESET protein expression at the knee joint was assessed by an anti-ESET antibody in wild-type and ESET-null mice. DAPI counterstaining of nuclei was used for tissue outline. Arrows indicate strong staining for ESET protein in subchondral bone marrow cells. c, coronal sections of 2-week-old knee joints were stained by H&E for cell morphology and by Safranin O for proteoglycans (red). Scale bar: 400 μm.

Because the knee represents a major weight-bearing joint covered on both ends by articular cartilage, in this study, we have focused on the effects of ESET knock-out on the knee joint. To examine ESET expression in articular cartilage, we carried out immunohistostaining of knee sections using an anti-ESET antibody. As shown in Fig. 1b, ESET protein is found in chondrocytes within the articular cartilage in wild-type mice. In (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mutant mice, ESET protein is evidently eliminated from chondrocytes within the articular cartilage. ESET-positive staining is present in the medullary cavities of both wild type and (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mutants.

Two weeks after birth, the knee joints in wild-type (n = 3) and (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mice (n = 3) did not exhibit much phenotypic difference when examined by histological staining (Fig. 1c). Although the mutant mice lacked epiphyseal plates that are responsible for postnatal growth of the long bones, the gross morphology and thickness of articular cartilage covering the femoral condyles and tibial plateau in (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mice were similar to those of the wild-type mice.

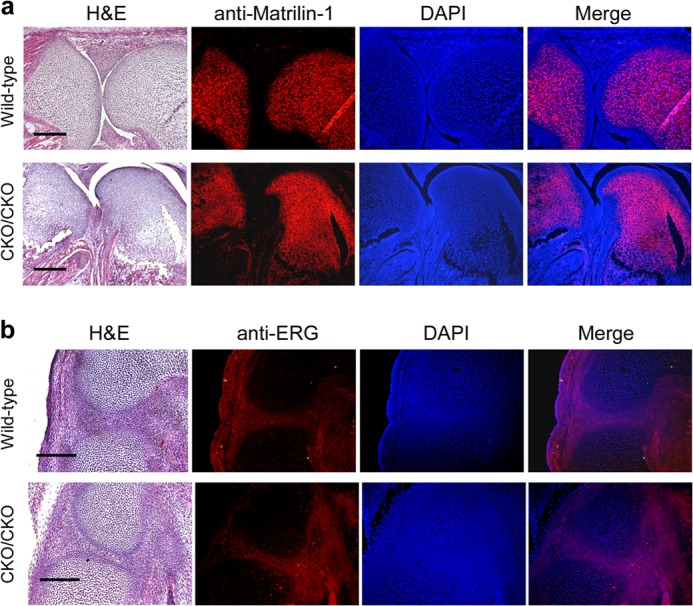

ESET Knock-out Does Not Affect Generation of Articular Chondrocytes

It is possible that mesenchyme-specific knock-out of ESET could block the normal generation of articular chondrocytes during embryonic development. ESET-null mice thus may lack articular cartilage, and chondrocytes seen at the joints of (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mutants could actually be derived from epiphyseal chondrocytes that now extend to the joint surface. To rule out such a possibility, we performed immunohistostaining for matrilin-1, a matrix protein that is known to be excluded from articular cartilage (9). As shown in Fig. 2a, although epiphyseal chondrocytes stained strongly for matrilin-1, a thin layer of cartilage near the joint surface is indeed negative for matrilin-1 in wild-type E18.5 embryos (n = 3). Similar exclusion of matrillin-1 from articular cartilage near the joint surface is also evident in ESET-null embryos (n = 3).

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of articular chondrocytes in ESET-null embryos. a, sagittal sections of knee joints from E18.5 embryos were stained by H&E or with an anti-matrilin-1 antibody. DAPI counterstaining of nuclei was used for tissue outline. The images were merged to show the absence of matrilin-1 in articular cartilage. b, sagittal sections of developing knee from E15.5 embryos were stained by H&E or with a rabbit antibody to show similar ERG expression within future joints in both wild-type and ESET-null embryos. A total of three wild-type and three knock-out embryos were examined, and results from a typical experiment are shown. Genotypes of the embryos are indicated on the left side. Scale bars: 400 μm (a), 200 μm (b).

To further confirm that formation of articular chondrocytes is not affected by ESET knock-out during joint development, we examined expression of ERG, an ETS family transcription factor whose mRNA has been reported to accumulate at the forming synovial joint but absent from growth plate cartilage (10, 11). As shown in Fig. 2b, immunohistostaining with an anti-ERG antibody confirmed expression of ERG protein at the developing knee joint in both wild type (n = 3) and (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mutants (n = 3) at the E15.5 stage. Together, these results indicate that mesenchyme-specific ESET knock-out does not seem to impair generation of articular chondrocytes.

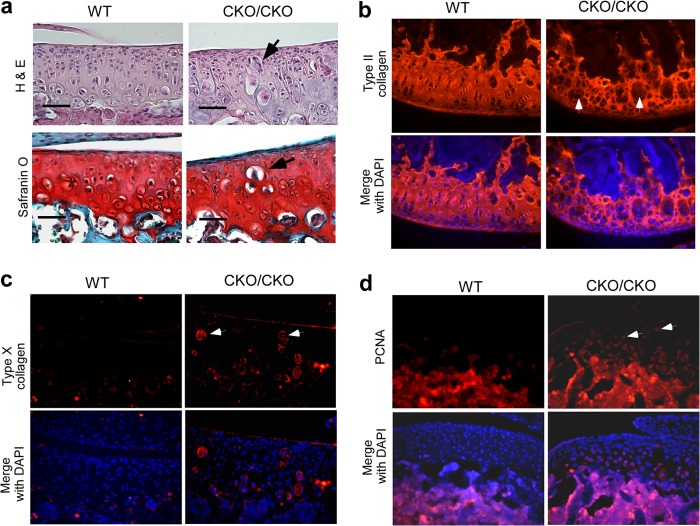

ESET Knock-out Promotes Hypertrophy and Proliferation in Articular Chondrocytes

We next monitored articular chondrocytes in adult animals to further investigate the effects of ESET deletion on the maintenance of articular cartilage. As shown in Fig. 3a, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of 1-month-old animals (n = 3 for wild type, n = 5 for knock-out) demonstrated the presence of hypertrophic chondrocyte-like cells near the superficial zone, the middle zone, and the deep zone in ESET-null articular cartilage, whereas such hypertrophic cells are absent in the wild-type counterparts. Immunohistostaining with an anti-type II collagen antibody indicated the existence of unusually large lacunae within the collagen network in (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mice, presumably occupied by the hypertrophic chondrocyte-like cells seen on H&E staining (Fig. 3b). To confirm that these cells are indeed hypertrophic chondrocytes, immunohistostaining was carried out with an anti-type X antibody. As shown in Fig. 3c, type X collagen-positive large chondrocytes were found throughout the articular cartilage in (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mice, whereas no such staining was seen in the articular cartilage of wild-type controls. In addition, articular chondrocytes in (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mice stained positive for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), a well known marker for cell proliferation (12, 13). In contrast, articular chondrocytes in the wild-type animals normally do not proliferate and are negative for PCNA staining (Fig. 3d).

FIGURE 3.

Articular chondrocyte hypertrophy and proliferation in 1-month-old ESET-null mice. a, 1-month-old knee joints were stained by H&E and Safranin O for detailed morphological analysis. b, 1-month-old knee sections were stained with an anti-type II collagen antibody. The type II collagen network was stained red, and nuclei were stained blue by DAPI. c, anti-type X collagen antibody specifically stains hypertrophic chondrocytes (red) in 1-month-old knee sections. d, anti-PCNA antibody detects cells positive for the proliferation marker in 1-month-old knee sections. Arrows in a–d indicate locations of hypertrophic or proliferative chondrocytes near the superficial zone in ESET-null mice. A total of three wild-type and five knock-out mice were examined, and images from representative experiments are shown. Genotypes of the mice are indicated on the top. Scale bar: 50 μm.

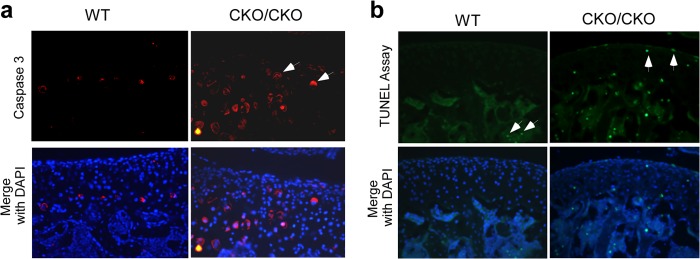

ESET Knock-out Causes Apoptosis in Articular Chondrocytes

Chondrocyte hypertrophy is known to be associated with programmed cell death. To show apoptosis among articular chondrocytes in ESET mutants at 1 month of age, we performed staining with an antibody against active caspase 3, an early apoptosis marker that is activated in apoptotic cells both by the extrinsic (death ligand) and by the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathways (14, 15). As confirmed in Fig. 4a, increased staining for active caspase 3 was seen throughout the articular cartilage of 1-month-old ESET knock-out mice (n = 3 for wild type, n = 5 for knock-out). To further confirm that increased staining for active caspase 3 correlates with DNA fragmentation (the last phase of apoptosis) in articular chondrocytes (16, 17), we performed TUNEL assay on the knee sections of ESET-null mutants. Although we did not find any TUNEL assay-positive articular chondrocytes at the knee joints of 1-month-old wild-type animals, positive TUNEL assay staining was readily detectable at the knee joints of 1-month-old ESET knock-out mice (Fig. 4b). These results indicate that expression of ESET protein is essential to the blockage of apoptosis that would otherwise take place even in the articular chondrocytes of young adult animals.

FIGURE 4.

Apoptosis of articular chondrocytes in 1-month-old ESET-null mice. a, 1-month-old knee sections were stained with an anti-active caspase 3 antibody, and nuclei were stained blue by DAPI. b, TUNEL assay was performed on knee sections to measure DNA fragmentation in situ. Arrows in a indicate early stage apoptotic chondrocytes (red), and arrows in b designate late-stage apoptotic nuclei (green). A total of three wild-type and five knock-out mice were examined, and representative experiments are shown. Genotypes of the mice are indicated on the top.

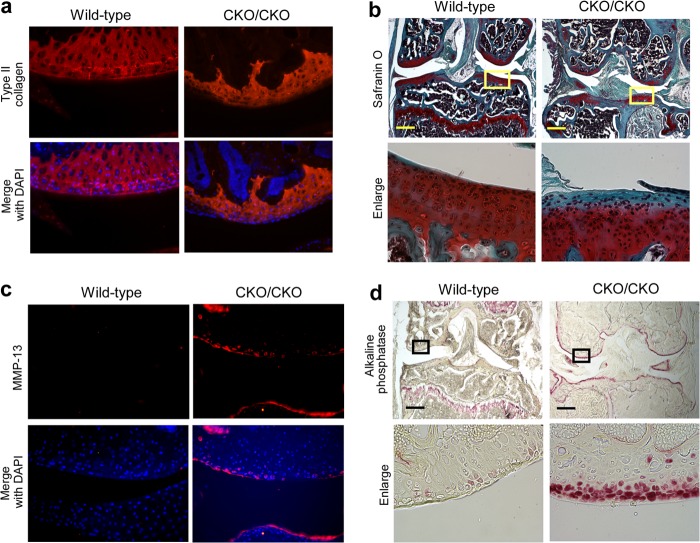

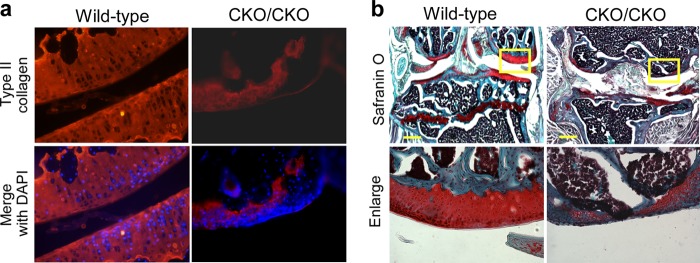

ESET Knock-out Accelerates Degeneration of Articular Cartilage

Analysis of the ESET-null mice at 3 months demonstrated a marked decrease in articular cartilage thickness as indicated by decreased type-II collagen staining (Fig. 5a). A merged image with DAPI allows for the visualization of type II collagen staining in relationship to the articular chondrocytes. When measured in multiple animals (n = 3 each for wild type and knock-out), the average cartilage thickness at the lateral condyle in (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mice was about 40% of that found in sex- and age-matched wild-type animals. Additionally at this age, as shown in Fig. 5b, the superficial zones of the articular cartilage in ESET-null mice were no longer stained positive by Safranin O, an indication that portions of the joint surface had lost their proteoglycan content.

FIGURE 5.

Terminal differentiation of articular chondrocytes in 3-month-old ESET-null mice. a, a significant decrease of the type II collagen network was evident when the joints were stained with an anti-type II collagen antibody. b, the knee joints were stained by Safranin O to assess changes in articular cartilage. Lower panels represent enlargements of the selected areas in the top panels. Negative staining within the superficial zone in the knock-out indicates loss of proteoglycans. c, positive staining (red) for MMP-13 in the articular cartilage was found only in ESET-null mice but not in wild-type controls. d, alkaline phosphatase activity was nearly undetectable in wild-type articular cartilage, but ESET-null chondrocytes close to the articular surface all stained positive for alkaline phosphatase activity. Lower panels represent enlargements of the selected areas in the top panels. A total of three wild-type and three knock-out mice were examined, and representative experiments are shown. Scale bar: 400 μm.

MMP-13 is a marker for terminal differentiation and the most active collagenase against type II collagen, the main component of articular cartilage (18). During embryogenesis, MMP-13 is expressed by hypertrophic chondrocytes at the epiphyseal plate, and its proteolytic activity is responsible for reorganization of the cartilaginous analgen, which allows growth and ossification (19). When assessed for MMP-13 in the ESET-null mice, as shown in Fig. 5c, MMP-13 protein was also detected in the superficial zone of ESET-null animals in addition to expression in the subchondral region. In contrast, a total absence of MMP-13 in the articular cartilage is evident in wild-type animals.

To further confirm that articular chondrocytes in ESET-null mice had undergone changes in phenotype, we performed an assay for ALP, which is yet another marker for terminal differentiation of chondrocytes. As shown in Fig. 5d, ALP activity in wild-type mice was mainly detected in bone cavities and remnant of the epiphyseal plate. In (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mice, however, ALP activity was found mainly in chondrocytes at or near the articular surface, suggesting that these chondrocytes had progressed to terminal differentiation.

Because (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mice can live for more than 1 year, we also examined the knee joints in 1-year-old mice. Although wild-type mice showed normal thickness of articular cartilage at this age, degradation of articular cartilage in 12-month-old ESET-null mice was even more severe. It was noticed that cartilage at the joint in 12-month-old ESET-null mice was mostly surrounded by type II collagen-negative cells and that there was very little cartilage left to cover the joint surface. On average, the thickness of cartilage remnant at the lateral condyle in 12-month-old (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mice was less than 20% of that found in sex- and age-matched wild-type animals (n = 5 each for wild-type and knock-out mice). This confirms the notion that loss of type II collagen and proteoglycans seen at 3 months in ESET-null mice is progressive (Fig. 6, a and b).

FIGURE 6.

Degradation of articular cartilage in 12-month-old ESET-null mice. a, knee sections from 12-month-old mice were stained with an anti-type II collagen antibody. The type II collagen network was stained red, and nuclei were stained blue by DAPI. b, 12-month-old knee joints were stained by Safranin O for proteoglycans. Note the significant loss of type II collagen and proteoglycans at the joint in ESET-null mice. A total of five wild-type and five knock-out mice were examined, and images from representative experiments are shown. Genotypes of the mice are indicated on the top. Scale bar: 400 μm.

DISCUSSION

We have provided evidence that mesenchyme-specific ESET knock-out has little effect on embryonic development of articular chondrocytes. In the absence of ESET histone methyltransferase, however, adult articular chondrocytes fail to maintain their phenotype, which predisposes the articular cartilage to degeneration. It appears that both the loss of articular cartilage cellularity (due to chondrocyte hypertrophy followed by apoptosis) and an increase in collagenase activity (MMP-13) are responsible for degeneration of articular cartilage in ESET-null adult mice.

In this study, we have demonstrated that ESET is expressed in articular cartilage, that mesenchyme-specific knock-out of ESET causes ectopic hypertrophy and apoptosis in articular chondrocytes, and that terminal differentiation of articular chondrocytes predisposed articular cartilage in the knock-out animals to degeneration. It should be pointed out that we have analyzed more than 14 pairs of age- and sex-matched wild-type and (exons 15&16)CKO/CKO mice (with ages ranging from 2 weeks to 12 months), and all ESET mutant mice exhibited similar defects described here. The articular chondrocyte phenotype found in ESET knockouts is therefore 100% penetrant. Our findings support the notion that a similar mechanism controls the differentiation of both growth plate chondrocytes and articular chondrocytes through sharing a common set of regulatory factors such as ESET.

In normal growth plate development, chondrocytes at various differentiation stages are all organized in specific zones, and chondrocytes mature in an orderly sequence. In this study, we observed hypertrophy of articular chondrocytes taking place in 1-month-old mutants but not in 3-month-old mutants. Also, only a fraction of articular chondrocytes appear to be hypertrophic at 1 month in these knockouts. Why did hypertrophy not occur in all of the articular chondrocytes in a synchronized manner? The answer could be that articular chondrocytes are not uniform in behavior. In addition to being subdivided into three histological zones (superficial zone at the surface, transitional zone in the middle, and deep zone near the calcified cartilage), articular chondrocytes within the same zone may also exhibit individual differences due to changes in microenvironment such as topographical variations (20–22). It appears that by 3 months, articular chondrocytes that are susceptible to hypertrophy in the face of ESET knock-out are long gone, and the effects of ESET deletion on the remaining articular chondrocytes are manifested not through hypertrophy but through other changes such as elevated ALP and MMP-13 expression. Despite this heterogeneity in chondrocyte responses, one constant observation remains that ESET-null articular cartilage is defective and invariably undergoes premature degeneration in all mutant animals.

ESET belongs to a group of proteins (Suv39h, G9a, GLP, and ESET) that are responsible for specific methylation of H3-K9 (23). As a major epigenetic marker, H3-K9 methylation is known as a “histone code” for gene silencing. Interestingly, a recent study showed that H3-K9 methylation in the promoter region of NFAT1, an essential transcriptional regulator of articular cartilage homeostasis, determines its age-dependent expression in articular chondrocytes (24). In addition, transgenic studies have shown that ERG protein (with which ESET is known to associate) regulates the developmental behavior of most epiphyseal chondrocytes and helps them acquire a permanent articular chondrocyte phenotype in embryos (11).

What could be the underlying mechanism responsible for such an accelerated degeneration of articular cartilage in adult ESET-null mice? We noticed that the activities of both ALP and MMP-13 are elevated in ESET-null articular cartilage, and both genes are well known downstream targets of Runx2 protein (25–27). In our recent studies to understand the molecular mechanisms governing ESET regulation of growth plate chondrocytes, we have found that overexpressed ESET protein (together with HDAC4) physically interacts with and functionally inhibits Runx2 and that repression of Runx2-mediated reporter gene transactivation by co-transfected ESET is dependent on its intrinsic H3-K9 methyltransferase activity (5). Because Runx2 is a hypertrophy-promoting transcription factor that is normally repressed in articular chondrocytes (28), we believe that ESET is also an essential component of a protein complex that represses Runx2 activity in articular chondrocytes and that specific knock-out of ESET in articular chondrocytes results in de-repression of Runx2 activity and ectopic expression of Runx2 target genes such as type X collagen and MMP-13 described in this study. This aberrant gene expression program in turn promotes hypertrophy and terminal differentiation of articular chondrocytes, leading to eventual destruction of articular cartilage at the joint.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. L. Carey for assistance in mouse breeding and Dr. Roberto Nicosia's laboratory for assistance in image acquisition.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 AR051455 (to L. Y.). This work was also supported by a Merit Review Award from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development Biomedical Laboratory Research Program (to H. A. C.).

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- ALP

- alkaline phosphatase

- ERG

- ETS-related gene

- ETS

- erythroblast transformation-specific

- PCNA

- proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- CKO

- conditional knock-out

- E

- embryonic day.

REFERENCES

- 1. van der Kraan P. M., van den Berg W. B. (2012) Chondrocyte hypertrophy and osteoarthritis: role in initiation and progression of cartilage degeneration? Osteoarthritis Cartilage 20, 223–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pitsillides A. A., Beier F. (2011) Cartilage biology in osteoarthritis–lessons from developmental biology. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 7, 654–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldring M. B. (2012) Chondrogenesis, chondrocyte differentiation, and articular cartilage metabolism in health and osteoarthritis. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 4, 269–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berenbaum F. (2013) Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!). Osteoarthritis Cartilage 21, 16–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang L., Lawson K. A., Teteak C. J., Zou J., Hacquebord J., Patterson D., Ghatan A. C., Mei Q., Zielinska-Kwiatkowska A., Bain S. D., Fernandes R. J., Chansky H. A. (2013) ESET histone methyltransferase is essential to hypertrophic differentiation of growth plate chondrocytes and formation of epiphyseal plates. Dev. Biol. 380, 99–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miao D., Scutt A. (2002) Histochemical localization of alkaline phosphatase activity in decalcified bone and cartilage. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 50, 333–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blackburn M. L., Chansky H. A., Zielinska-Kwiatkowska A., Matsui Y., Yang L. (2003) Genomic structure and expression of the mouse ESET gene encoding an ERG-associated histone methyltransferase with a SET domain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1629, 8–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Logan M., Martin J. F., Nagy A., Lobe C., Olson E. N., Tabin C. J. (2002) Expression of Cre recombinase in the developing mouse limb bud driven by a Prxl enhancer. Genesis 33, 77–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hyde G., Dover S., Aszodi A., Wallis G. A., Boot-Handford R. P. (2007) Lineage tracing using matrilin-1 gene expression reveals that articular chondrocytes exist as the joint interzone forms. Dev. Biol. 304, 825–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dy P., Smits P., Silvester A., Penzo-Méndez A., Dumitriu B., Han Y., de la Motte C. A., Kingsley D. M., Lefebvre V. (2010) Synovial joint morphogenesis requires the chondrogenic action of Sox5 and Sox6 in growth plate and articular cartilage. Dev. Biol. 341, 346–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iwamoto M., Tamamura Y., Koyama E., Komori T., Takeshita N., Williams J. A., Nakamura T., Enomoto-Iwamoto M., Pacifici M. (2007) Transcription factor ERG and joint and articular cartilage formation during mouse limb and spine skeletogenesis. Dev. Biol. 305, 40–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pfander D., Swoboda B., Kirsch T. (2001) Expression of early and late differentiation markers (proliferating cell nuclear antigen, syndecan-3, annexin VI, and alkaline phosphatase) by human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Am. J. Pathol. 159, 1777–1783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hall P. A., Levison D. A., Woods A. L., Yu C. C., Kellock D. B., Watkins J. A., Barnes D. M., Gillett C. E., Camplejohn R., Dover R., et al. (1990) Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) immunolocalization in paraffin sections: an index of cell proliferation with evidence of deregulated expression in some neoplasms. J. Pathol. 162, 285–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Porter A. G., Jänicke R. U. (1999) Emerging roles of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 6, 99–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jänicke R. U., Sprengart M. L., Wati M. R., Porter A. G. (1998) Caspase-3 is required for DNA fragmentation and morphological changes associated with apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9357–9360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gavrieli Y., Sherman Y., Ben-Sasson S. A. (1992) Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J. Cell Biol. 119, 493–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang C., Li S. W., Helminen H. J., Khillan J. S., Bao Y., Prockop D. J. (1997) Apoptosis of chondrocytes in transgenic mice lacking collagen II. Exp. Cell Res. 235, 370–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mitchell P. G., Magna H. A., Reeves L. M., Lopresti-Morrow L. L., Yocum S. A., Rosner P. J., Geoghegan K. F., Hambor J. E. (1996) Cloning, expression, and type II collagenolytic activity of matrix metalloproteinase-13 from human osteoarthritic cartilage. J. Clin. Invest. 97, 761–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Inada M., Wang Y., Byrne M. H., Rahman M. U., Miyaura C., López-Otín C., Krane S. M. (2004) Critical roles for collagenase-3 (Mmp13) in development of growth plate cartilage and in endochondral ossification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 17192–17197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aydelotte M. B., Kuettner K. E. (1988) Differences between sub-populations of cultured bovine articular chondrocytes. I. Morphology and cartilage matrix production. Connect. Tissue Res. 18, 205–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Quinn T. M., Hunziker E. B., Häuselmann H. J. (2005) Variation of cell and matrix morphologies in articular cartilage among locations in the adult human knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 13, 672–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xia Y., Moody J. B., Alhadlaq H., Burton-Wurster N., Lust G. (2002) Characteristics of topographical heterogeneity of articular cartilage over the joint surface of a humeral head. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 10, 370–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kouzarides T. (2007) SnapShot: Histone-modifying enzymes. Cell 131, 822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rodova M., Lu Q., Li Y., Woodbury B. G., Crist J. D., Gardner B. M., Yost J. G., Zhong X. B., Anderson H. C., Wang J. (2011) Nfat1 regulates adult articular chondrocyte function through its age-dependent expression mediated by epigenetic histone methylation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 1974–1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang X., Manner P. A., Horner A., Shum L., Tuan R. S., Nuckolls G. H. (2004) Regulation of MMP-13 expression by RUNX2 and FGF2 in osteoarthritic cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 12, 963–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen C. G., Thuillier D., Chin E. N., Alliston T. (2012) Chondrocyte-intrinsic Smad3 represses Runx2-inducible matrix metalloproteinase 13 expression to maintain articular cartilage and prevent osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 64, 3278–3289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weng J. J., Su Y. (2013) Nuclear matrix-targeting of the osteogenic factor Runx2 is essential for its recognition and activation of the alkaline phosphatase gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1830, 2839–2852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kamekura S., Kawasaki Y., Hoshi K., Shimoaka T., Chikuda H., Maruyama Z., Komori T., Sato S., Takeda S., Karsenty G., Nakamura K., Chung U. I., Kawaguchi H. (2006) Contribution of runt-related transcription factor 2 to the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis in mice after induction of knee joint instability. Arthritis Rheum. 54, 2462–2470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]