Background: The Cys-62/Cys-69 dithiol of Trx1 is predicted to have a profound effect on cell signaling.

Results: The Cys-62/Cys-69 dithiol of Trx1 was oxidized by Prx1, and this disulfide was reduced by the GSH/glutaredoxin system.

Conclusion: Trx1 is involved in redox regulation via reversible oxidation of the Cys-62/Cys-69 dithiol of Trx1.

Significance: We demonstrated the critical role of Trx1 oxidation in cell signaling.

Keywords: Hydrogen Peroxide, Oxidative Stress, Peroxiredoxin, Redox Signaling, Thiol, Thioredoxin

Abstract

The mammalian cytosolic thioredoxin system, comprising thioredoxin (Trx), Trx reductase, and NADPH, is the major protein-disulfide reductase of the cell and has numerous functions. Besides the active site thiols, human Trx1 contains three non-active site cysteine residues at positions 62, 69, and 73. A two-disulfide form of Trx1, containing an active site disulfide between Cys-32 and Cys-35 and a non-active site disulfide between Cys-62 and Cys-69, is inactive either as a disulfide reductase or as a substrate for Trx reductase. This could possibly provide a structural switch affecting Trx1 function during oxidative stress and redox signaling. We found that two-disulfide Trx1 was generated in A549 cells under oxidative stress. In vitro data showed that two-disulfide Trx1 was generated from oxidation of Trx1 catalyzed by peroxiredoxin 1 in the presence of H2O2. The redox Western blot data indicated that the glutaredoxin system protected Trx1 in HeLa cells from oxidation caused by ebselen, a superfast oxidant for Trx1. Our results also showed that physiological concentrations of glutathione, NADPH, and glutathione reductase reduced the non-active site disulfide in vitro. This reaction was stimulated by glutaredoxin 1 via the so-called monothiol mechanism. In conclusion, reversible oxidation of the non-active site disulfide of Trx1 is suggested to play an important role in redox regulation and cell signaling via temporal inhibition of its protein-disulfide reductase activity for the transmission of oxidative signals under oxidative stress.

Introduction

Thioredoxins are a family of small proteins that catalyze thiol-disulfide oxidoreductions by using redox-active cysteine residues in their active site (WCGPC), which is conserved among species from cyanobacteria to humans (1–4). Thioredoxin (Trx),3 Trx reductase (TrxR), and NADPH compose the Trx system, which operates by transferring electrons from NADPH via TrxR to the active site of Trx. The active site cysteines of Trx are readily accessible on the surface of the protein and become oxidized to a disulfide upon reduction of a target protein. This disulfide is cycled back to dithiol by TrxR (4, 5). Trx is the major disulfide reductase with a large number of functions in cells. These involve DNA synthesis via ribonucleotide reductase, reduction of methionine sulfoxide reductase, and particularly defense against oxidative stress by providing the electrons to peroxiredoxins (Prxs). In addition, Trx in its reduced form plays important roles in redox regulation of many transcription factors, such as NF-κB, Ref-1 (redox factor-1), ASK1 (apoptosis signaling kinase-1), and AP-1 (activator protein-1) (4, 6, 7). For example, reduced Trx1 can bind and inactivate ASK1, a MAPK kinase kinase that can induce apoptosis (8). In vivo Trx activity may be regulated by binding to Trx-interacting protein (Txnip) (9–11).

Mammalian cells contain two distinct Trxs. Trx1 is localized in the cell cytosol/nucleus, whereas Trx2 is a mitochondrial protein (4). In addition to the active site Cys-32 and Cys-35, mammalian Trx1 has three non-active site cysteine residues (Cys-62, Cys-69, and Cys-73), which have been suggested to be important for regulating the activity and function of Trx1 (12). Cys-62 and Cys-69 are within helix α3, and Cys-73 is on a hydrophobic patch of surface of the protein. Cys-73 is present as an intermolecular disulfide bond (Trx1 homodimer) in x-ray crystal studies (13, 14). Mass spectrometry data reveal a second intramolecular disulfide besides the active site disulfide, formed between Cys-62 and Cys-69 under oxidizing conditions (14). The formation of the second disulfide between Cys-62 and Cys-69 impairs Trx1 activity and is predicted to have a profound effect by disrupting interactions between Trx and its target protein (6, 14, 15). In vitro, a two-disulfide form of Trx1 (Trx1-S4) is inactive either as a disulfide reductase or as a substrate for TrxR and is no longer an anti-apoptotic factor via ASK1, supporting the interpretation that oxidation of the non-active site dithiol could possibly provide a structural switch affecting Trx1 function during oxidative stress and redox signaling (14, 16). However, it is unknown how this non-active site disulfide is generated and fulfills its biologic functions in redox signaling .

H2O2 was viewed as the inevitable but unwanted by-product of oxidative metabolism in cells. Prxs exert their protective antioxidant role in cells through their peroxidase activity, whereby H2O2 is reduced and scavenged. However, H2O2 has been revealed to possess important functions in cell signaling as a second messenger (11, 17). In the cytosol of mammalian cell, the Prxs appear to be involved in the redox regulation of cell signaling and differentiation by regulating the levels of H2O2 (18–20). However, the detailed mechanism of how H2O2 exerts its activity in redox regulation of cell signaling is still unclear.

In this study, we found that the oxidation of Trx1 was catalyzed by Prx1 in the presence of H2O2, suggesting that the non-active site cysteines were able to transfer electrons to Prx1 and therefore possibly had a reduction activity. The glutaredoxin (Grx) system could reduce the non-active site disulfide of Trx1, which was not a substrate of TrxR. Therefore, Trx1 might be involved in redox regulation of cell signaling via the temporal inactivation of its redox activity due to the reversible oxidation of the non-active site cysteines under oxidative stress.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals and Proteins

Buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), DTT, GSH, iodoacetic acid (IAA), iodoacetamide (IAM), insulin, and glutathione reductase were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ebselen was a product of Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co. (Tokyo, Japan). Wild-type human Trx1, human Grx1, Escherichia coli Grx1 C14S mutant protein, and anti-human Trx1 antibody were products of IMCO Ltd. (Stockholm, Sweden). Recombinant TrxR1 was a gift from Dr. Elias Arnér (Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska Institutet) and was purified as described (21).

Cell Culture

Human alveolar adenocarcinoma epithelial A549 cells and cervical carcinoma HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Biochrom) supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine, 10% FCS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in an incubator with 5% CO2.

Detection of Trx1 Redox State in Cells

The redox state of Trx1 was detected by a modified redox Western blot method described previously (22–24). To prepare mobility standards, cell lysates were denatured and unfolded with urea and fully reduced with DTT. Varying molar ratios of IAA to IAM were incubated with the reduced proteins containing n cysteines, producing n+1 protein isoforms with the introduced number of acidic carboxymethylthiol adducts (–SA−) and neutral amidomethylthiol adducts (–SM). During urea-PAGE, the ionized –SA− adducts resulted in faster protein migration toward the anode. Therefore, the n+1 isoforms were separated and used as a mobility standard for representing the number of –SA−. To determine the redox state of Trx1 in vivo, cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed in 300 μl of urea lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 1 mm EDTA, and 8 m urea) containing 10 mm IAM. Free thiols were alkylated by IAM at 37 °C for 20 min. After removing the cell debris by centrifugation, the cell lysates were precipitated by ice-cold acetone HCl. The precipitate was washed with ice-cold acetone HCl two more times and resuspended in 100 μl of urea lysis buffer containing 3.5 mm DTT. After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, 5 μl of 600 mm IAA was added to each sample and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The protein concentration was determined by the Lowry protein assay, and equal amounts of protein were separated by urea-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). Membranes were probed with the appropriate primary antibody, biotinylated secondary antibody (Dako), and streptavidin/HRP-conjugated anti-biotin tertiary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then visualized using Western Lightning Plus chemiluminescence reagent (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Construction of Plasmid for Human Trx1 Mutant (Trx1SGPS)

Primers to construct the C32S/C35S (SGPS) mutant (with a Ser-Gly-Pro-Ser sequence) of pET-16b/Trx were from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The forward primer was 5′-GC GGT CTC GGG CCT TCC AAA ATG ATC AAG CCT TTC-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-GC GGT CTC AGG CCC AGA CCA CGT GGC TGA GAA GTC-3′. The site-directed mutagenesis plasmid was constructed using the inverse PCR method (25). The existence of the mutation was verified by sequencing.

Purification of Recombinant Human Prx1 and Trx1SGPS

E. coli strain BL21 was transformed with plasmid pNIC-Bsal, encoding Homo sapiens Prx1 (NM_181696), or plasmid pET-16b, encoding Trx1SGPS. Proteins were expressed by the autoinduction method (26) at 20 °C in autoinduction Terrific Broth medium. Cultures were collected and lysed in 50 mm Tris-HCl, and the clear lysates were subjected to a nickel affinity chromatography for protein purification.

Redox State Shift of Human Trx1-S2 and Trx1SGPS in the Presence of Prx1 and/or H2O2

Trx1-S2, which contains an active site disulfide and three non-active site thiols, was prepared as follows. 0.6 mm human Trx1 in 50 mm Tris-HCl and 1 mm EDTA (pH 7.5) was reduced by 3.5 mm DTT, and the sample was desalted on a Sephadex G-25 gel filtration column to remove excess DTT. 90 μm reduced Trx1 was incubated with 45 μm insulin at room temperature for 30 min, and the sample was spun at 16,000 × g for 5 min to remove precipitated insulin. The redox state of Trx1-S2 was verified by redox urea-PAGE. 10 μm Trx1-S2 or reduced Trx1SGPS was incubated with various concentrations of Prx1/H2O2 for 5 min at 37 °C. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 10 mm IAM to the reaction solutions, which also fixed the redox state of Trx1 at the same time. These samples were subjected to a redox urea-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie Blue staining.

Activity Assay for Reduction of Oxidized Trx1

Human Trx1 and Trx1SGPS protein were oxidized with 5 mm H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature and then desalted using a Sephadex G-25 gel filtration column. The assay system was composed of 0.25 mm NADPH, 45 nm glutathione reductase, and the indicated amounts of GSH and Trx1/Trx1SGPS with or without Grx1 in 50 mm Tris-HCl and 1 mm EDTA (pH 7.5) in a cuvette. Consumption of NADPH was determined by monitoring the absorbance change at 340 nm.

RESULTS

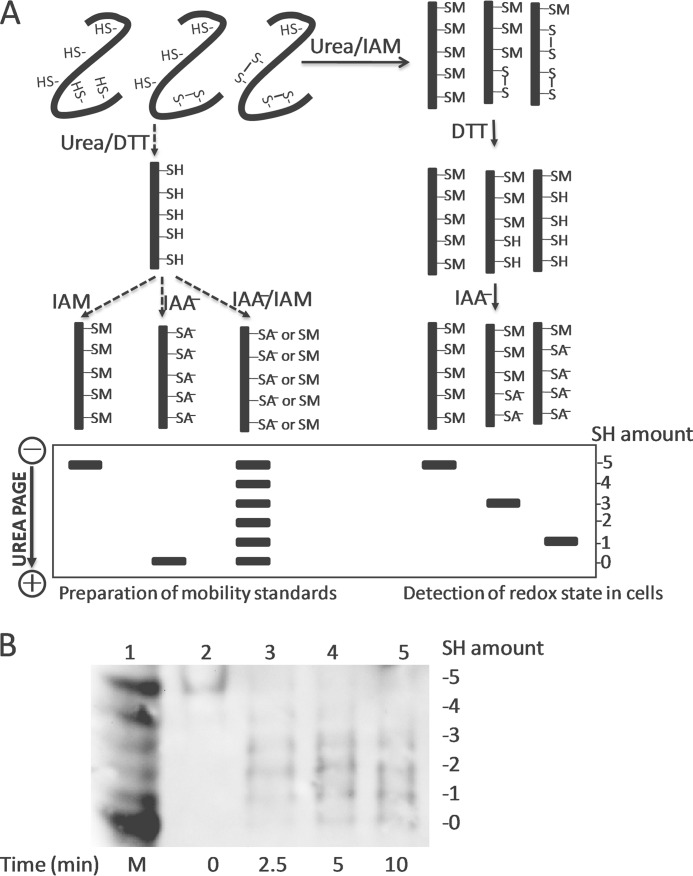

Cellular Redox State Response of Trx1 to Oxidative Stress

The precise mechanism of the transmission of oxidative signals under oxidative stress was not well understood. In this study, we explored the role of Trx1 in redox signaling under oxidative stress. We treated A549 cells with a high concentration of H2O2 as an oxidative stress source, and the redox state of Trx1 in cells was detected using a modified redox Western blot method. In the classic redox Western blot method (22–24), cells were lysed by 8 m urea containing IAA to alkylate the free thiols of Trx1. However, the rate for the alkylation of Trx1 with IAM was found to be 20-fold faster than that with IAA (27). Therefore, we used IAM instead of IAA to alkylate the free thiols of Trx1 in the modified method, which would be beneficial to decrease the risk of oxidation of Trx1 during the cell lysis process. It should be noted that the nitrosylated or glutathionylated cysteines behave the same as the cysteines which form disulfide bonds in the redox Western blot assay. Therefore, in Table 1, we summarized the most likely forms of Trx1 for each band shown in this assay.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the most likely forms of Trx1 for each band in redox Western blotting

| Band | Most likely forms of Trx |

|---|---|

| 5 | Trx-(SH)5 |

| 4 | (SH)4-Trx-S-S-Trx-(SH)4 |

| Trx-(SH)4S-proteina | |

| Trx-(SH)4S-SGb | |

| Trx-(SH)4S-NOc | |

| 3 | Trx-(SH)3S2 |

| 2 | (SH)2S2-Trx-S-S-Trx-S2(SH)2 |

| Trx-(SH)2S2S-SG | |

| Trx-(SH)2S2S-NO | |

| 1 | Trx-S4(SH) |

| 0 | S4-Trx-S-S-Trx-S4 |

| Trx-S4S-SG | |

| Trx-S4S-NO |

a Disulfide between Trx1 and some specific proteins, such as Txnip and ASK1.

b Glutathionylation of Trx1.

c Nitrosylation of Trx1.

As shown in Fig. 1, the physiological state of Trx1 in the untreated cells was fully reduced, in line with a previous report (24). Under oxidative stress, the redox state of Trx1 shifted from the fully reduced state to the oxidized state. It should be noted that the two-disulfide form of Trx1 with or without a free thiol was observed under oxidative stress. As shown in Table 1, band 0 represents the form containing two disulfides (Cys-32/Cys-35 and Cys-62/Cys-69) and a modified cysteine (Cys-73). The modification of Cys-73 might be glutathionylation, nitrosylation, or the disulfide between Cys-73 of two Trx1 molecules (7). In any case, the non-active site disulfide was resistant to regeneration by TrxR1, and therefore, the two-disulfide form of Trx1 was inactive, which would allow time for redox-dependent signaling processes to occur.

FIGURE 1.

Redox state of Trx1 in A549 cells under oxidative stress. A, principle of redox Western blot analysis. To prepare mobility standards, cell lysates were denatured with urea and fully reduced with DTT. Varying molar ratios of IAA to IAM were incubated with the reduced Trx1 containing five cysteines, producing six protein isoforms with the introduced number of acidic carboxymethylthiol adducts (–SA−) and neutral amidomethylthiol adducts (–SM). During urea-PAGE, the ionized –SA− group resulted in faster protein migration toward the anode. Therefore, the six isoforms were separated and used as a mobility standard for representing the number of –SA−. To determine the redox state of Trx1 in cells, cells were lysed in urea lysis buffer containing IAM. After the free thiols of Trx1 were alkylated by IAM, cell lysates were precipitated by ice-cold acetone HCl. The precipitate was washed with ice-cold acetone HCl two more times to remove excess IAM. The precipitate was then resuspended in urea lysis buffer containing DTT to reduce the disulfides of Trx1. The free thiols of Trx1 were alkylated by IAA. The alkylated Trx1 in cell lysates was separated according to the charge amount, representing the initial amount of free thiols of Trx1. B, A549 cells were exposed to oxidative stress (15 mm H2O2) for the indicated times (lanes 2–5), and the redox state of Trx1 in A549 cells was detected by redox Western blot analysis. Lane 1, artificial mobility standards (M).

In Vitro Oxidation of the Non-active Site Thiols of Trx1 in the Presence of Prx1 and/or H2O2

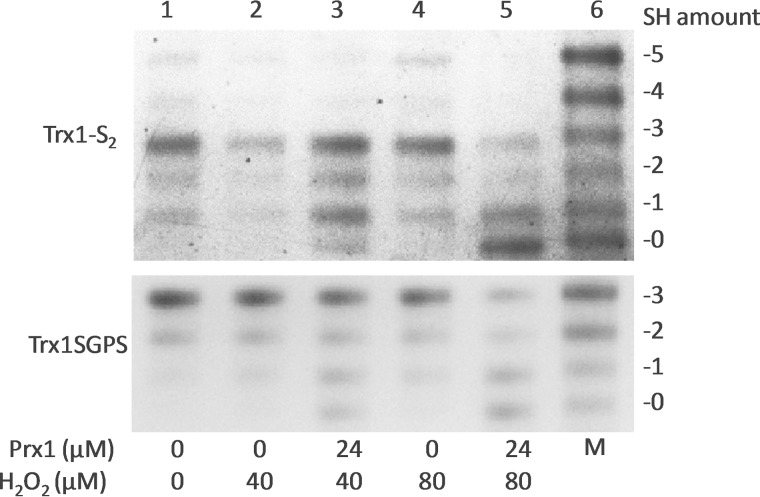

Because H2O2 is reduced and scavenged by Prx1 using Trx1 as the electron donor, it is important to understand the effect of H2O2 on the formation of the non-active site disulfide of Trx1 in the presence/absence of Prx1. First, we prepared oxidized wild-type Trx1 containing an active site disulfide and three non-active site thiols (Trx1-S2), as described under “Experimental Procedures,” which was verified on redox gel as shown in Fig. 2 (upper panel, lane 1). A physiological concentration of Trx1-S2 was incubated with H2O2 in the presence/absence of Prx1. H2O2 was not an effective oxidant for the formation of the non-active site disulfide of Trx1 in the absence of Prx1 (lanes 2 and 4); however, in the presence of Prx1, the formation of Trx1-S4 (bands 1 and 0 in lanes 3 and 5) was strongly stimulated, indicating that H2O2 indirectly induced formation of Trx1-S4 via Prx1. A similar result was obtained using pre-reduced Trx1SGPS, which contained only three non-active site thiols (Fig. 2, lower panel).

FIGURE 2.

Redox state shift of human Trx1-S2 and Trx1SGPS in the presence of Prx1 and/or H2O2. Trx1-S2 was prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures.” 10 μm Trx1-S2 or reduced Trx1SGPS was incubated with the indicated concentrations of Prx1/H2O2 (lanes 1–5) for 5 min at 37 °C. The redox state of Trx1 and Trx1SGPS was detected by redox urea-PAGE analysis. Lane 6, artificial mobility standards (M).

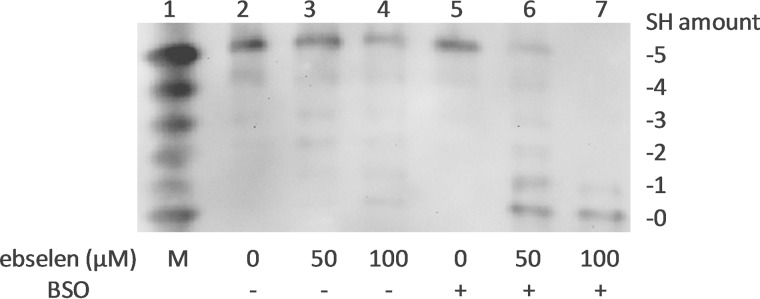

The GSH System Protects Cellular Trx1 from Oxidation

The GSH system is another important antioxidant system in addition to the Trx system in cells. In our study, HeLa cells were pretreated with BSO, an inhibitor of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase, to deplete cellular GSH. Untreated or BSO-pretreated cells were incubated with ebselen, which is a substrate for both TrxR1 and Trx1 and a superfast oxidant for Trx1 (28). As shown in Fig. 3, most of the Trx1 in the cells without BSO pretreatment remained in the fully reduced state after incubation with ebselen (lanes 2–4). However, after incubation with ebselen, the redox state of Trx1 in the cells with BSO pretreatment shifted from the fully reduced state to the oxidized state (lanes 5–7), indicating that the GSH system protected Trx1 from oxidation in vivo.

FIGURE 3.

Redox state of Trx1 in HeLa cells treated with ebselen. HeLa cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of ebselen for 2 h with or without 0.1 mm BSO pretreatment (lanes 2–7). The redox state of Trx1 in HeLa cells was detected with by redox Western blot analysis. Lane 1, artificial mobility standards (M).

The GSH System Is an Electron Donor for Reduction of the Non-active Site Disulfide of Human Trx1

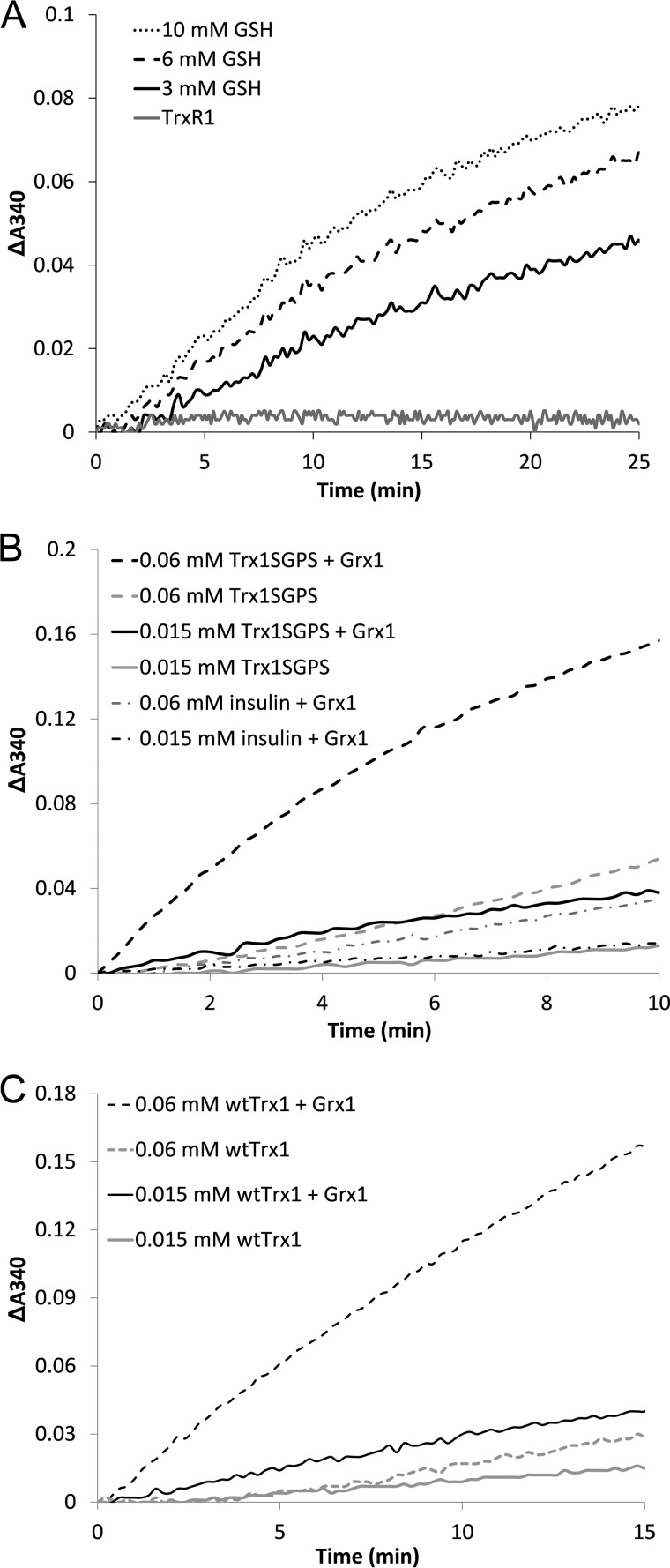

On the basis of the results obtained in the above experiment, we further tested whether the GSH system acts as an electron donor for reduction of the non-active site disulfide of human Trx1. The physiological concentration of GSH is in the millimolar range in cells, so we used a millimolar concentration of GSH in the activity assays. As shown in Fig. 4A, TrxR1 was unable to reduce oxidized Trx1SGPS, in line with a previous report (14). However, physiological concentrations of GSH showed the ability to reduce the non-active site disulfide of Trx1SGPS (Fig. 4A) in the presence of glutathione reductase and NADPH. Additional experiments performed in the presence of human Grx1 showed that this reduction was strongly enhanced by Grx1 (Fig. 4B). We also performed the activity assay using Trx1-S4 as the substrate and obtained a similar result (Fig. 4C). Because of the high background of GSH in the reduction of Trx1SGPS and Trx1-S4, however, it was not possible to determine the kinetic constants of this reaction. Therefore, the efficiency of Grx1 in reducing Trx1SGPS and insulin was compared at the same concentration. As shown in Fig. 4B, Grx1 showed a higher efficiency in reducing Trx1SGPS compared with insulin.

FIGURE 4.

Reduction of oxidized Trx1SGPS and Trx1-S4 by the GSH/Grx system. A, 45 nm glutathione reductase, 0.25 mm NADPH, and 20 μm oxidized Trx1SGPS were added to cuvettes for the GSH reduction assay in the presence of 3 (solid black line), 6 (dashed line), and 10 (dotted line) mm GSH. 0.25 mm NADPH and 20 μm oxidized Trx1SGPS were added to cuvettes for the TrxR1 reduction assay in the presence of 10 nm TrxR1 (solid gray line). The absorbance change at 340 nm was monitored. B, 45 nm glutathione reductase, 0.25 mm NADPH, 1 mm GSH, and the indicated amounts of oxidized Trx1SGPS/insulin were added to cuvettes for the reduction assay with or without 1 μm human Grx1. The absorbance change at 340 nm was monitored. C, 45 nm glutathione reductase, 0.25 mm NADPH, 1 mm GSH, and the indicated amounts of oxidized WT Trx1 were added to cuvettes for the reduction assay with or without 1 μm human Grx1. The absorbance change at 340 nm was monitored.

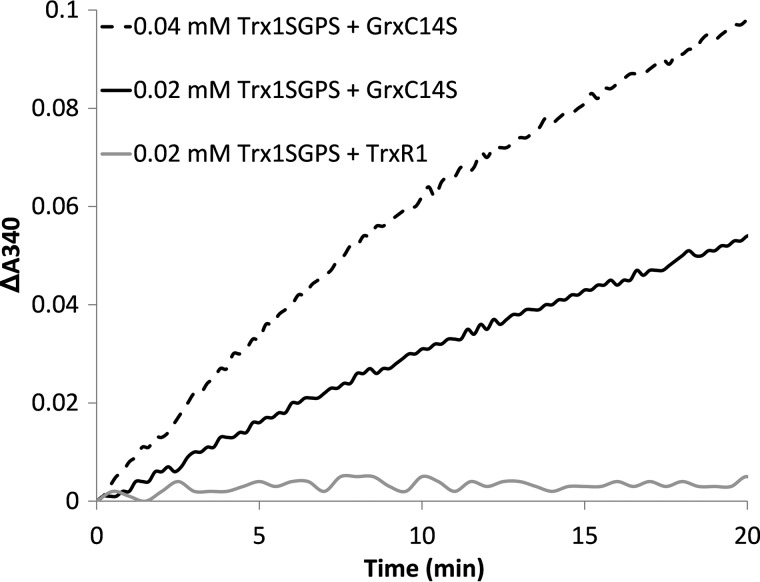

To explore the mechanism of the Grx system in reducing the non-active site disulfide of Trx1, the activity assay was performed with the E. coli Grx1 C14S mutant protein, which contained only one cysteine. As shown in Fig. 5, E. coli Grx1 C14S showed the ability to reduce oxidized Trx1SGPS in the presence of GSH, glutathione reductase, and NADPH, indicating that the reaction catalyzed by Grx1 followed the monothiol mechanism.

FIGURE 5.

Reduction of oxidized Trx1SGPS by the E. coli Grx1 C14S mutant protein. 45 nm glutathione reductase, 0.25 mm NADPH, 1 mm GSH, and 20 (solid black line) or 40 (dashed line) μm oxidized Trx1SGPS were added to cuvettes for the Grx reduction assay in the presence of 1 μm E. coli Grx1 C14S (GrxC14S) mutant protein. 0.25 mm NADPH and 20 μm oxidized Trx1SGPS were added to cuvettes for the TrxR1 reduction assay in the presence of 10 nm TrxR1 (solid gray line). The absorbance change at 340 nm was monitored.

DISCUSSION

Trx1 plays important roles in redox regulation of signaling. All of the roles that have been reported so far are dependent on the active site thiols of Trx1. In this study, we demonstrated that the non-active site thiols of Trx1 also play important roles in redox regulation of cell signaling via reversible oxidation.

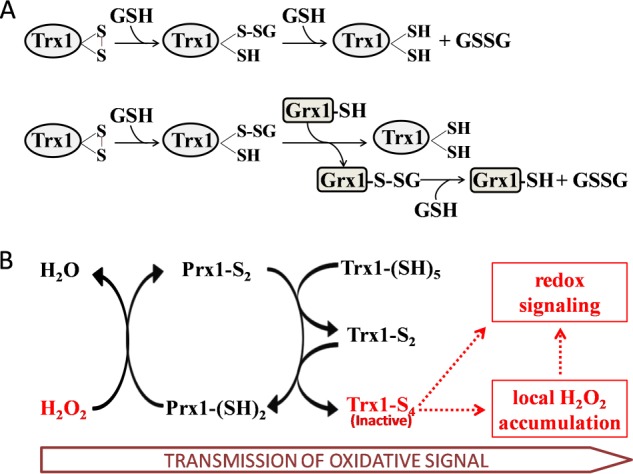

Although TrxR1 is responsible for reducing the active site disulfide bridge of Trx1, TrxR1 is unable to reactivate the non-active site disulfide of Trx1, so we wanted to determine if the oxidation of the non-active site thiols is reversible or not in cells. Fig. 3 suggests that Trx1 was protected by the GSH system from oxidation by ebselen in cells. In addition, we also found that the Grx system worked as an electron donor for reduction of the two-disulfide form of Trx1, which might allow oxidation of Trx1 in redox signaling to be reversible and regulatable under oxidative stress. The redox potential of the non-active site disulfide of human Trx1 is more positive than −210 mV, which is higher than that of the active site disulfide of human Trx1 at −230 mV (14). Because in vivo redox measurements of GSH in yeast and mammalian cells have confirmed a very reduced state for the cytosolic GSH/GSSG pool of −290 to −300 mV (29–31), the reaction is thermodynamically possible. It was reported previously that the Grx system also works as an electron donor for reduction of the active site disulfide of human Trx1 (24). In two-disulfide Trx1, the reduction of the active site disulfide might occur after the reduction of the non-active site disulfide because the redox potential of the non-active site dithiol is higher than that of the active site. We propose that the non-active site disulfide was reduced by GSH via a simple chemical reaction, as shown in Fig. 6A. Different from other protein-disulfide reductases, Grx1 also operated with a so-called monothiol mechanism, besides the classic two-thiol mechanism (32). On the basis of our results in Fig. 5, we propose that the reduction of oxidized Trx1 by the Grx1 system is a deglutathionylation reaction through the monothiol mechanism, as illustrated in Fig. 6. In fact, the cross-talk between the Trx and Grx systems with the catalytic disulfide of some plant Trxs reduced by the Grx systems has been reported previously, such as poplar Trx h4 (33, 34), Arabidopsis thaliana Trx h9 (35), and grape Trx h (Vitis vinifera CxxS2) (36). According to the authors, the reduction of plant Trx by the Grx system is a deglutathionylation reaction (37), which is as same as the mechanism proposed in our study.

FIGURE 6.

Proposed mechanism of Trx1-S4 in redox regulation and oxidative stress. A, proposed mechanism of reduction of oxidized Trx1 by GSH/Grx1. The non-active site disulfide is reduced by GSH via a simple chemical reaction. This reaction is stimulated by Grx1 through the monothiol mechanism. B, the oxidative signal is transmitted from H2O2 to Trx1-S4 via Prx1. Trx1-S4 is inactive and therefore results in Prx1 oxidation and H2O2 accumulation, which is involved in redox regulation, including inhibition of protein-tyrosine phosphatases and PTEN. The ASK1, NF-κB, p53, Ref-1, and AP-1 pathways will also benefit from the inactivation of Trx1.

Under oxidative stress, the inactivation of Trx1 via peroxide-induced oxidation that could not be reversed by TrxR1 may provide time for the transmission of oxidative signals. As shown by our results, oxidative stress via a short H2O2 treatment resulted in oxidation of cellular Trx1. It is very important to determine the mechanism of the formation of the two-disulfide form of Trx1 in cells under oxidative stress. We found that H2O2 alone was not an efficient oxidant for oxidation of Trx1. As a substrate of Prx1, H2O2 has more affinity for Prx1 than for Trx1. Therefore, Prx1 was more susceptible to oxidization by H2O2, and Prx1 (but not H2O2) oxidized Trx1 and gave rise to formation of the non-active site disulfide of Trx1. This might be similar to the case of Prx4, which is an endoplasmic reticulum resident protein with the capacity to couple H2O2 catabolism with oxidative protein folding. It was proposed that Prx4 is first oxidized by H2O2 to form a disulfide, and the disulfide of Prx4 is transferred to protein-disulfide isomerase thiols for oxidation of newly synthesized proteins to be folded (20, 38, 39).

More and more evidence confirms that H2O2 is primarily a signaling messenger rather than an evil oxidant (17, 40, 41). Many types of mammalian cells produce H2O2 for the purpose of intracellular signaling in response to stimulation through various cell surface receptors (17, 42). H2O2 acts by oxidizing the critical residues of effectors to allow temporal inhibition of the effectors, such as protein-tyrosine phosphatases (43) and the tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) (18). Presently, it is thought that the reversible inactivation of Prxs by H2O2 is involved in cell signaling. This is called the floodgate hypothesis. In this hypothesis, Prxs act as a peroxide floodgate, keeping peroxides away from susceptible targets until the floodgate is opened. Inactivation of Prxs occurs by overoxidation of the active site cysteine to sulfinic acid, and this permits accumulated H2O2 to then react with its targets (17, 19, 44). More recently, a report proposed that Prx2 is inactivated by hyperoxidation of its catalytic cysteine, whereas Prx1 is inactivated locally by phosphorylation but by hyperoxidation during H2O2 signaling at the cell membrane (20, 45). However, because Trx1 is an efficient electron donor to Prx1, Prx1 is not supposed to be inactive if Trx1 is still active. Therefore, we propose that inactivation of Trx1 is the mechanism that inactivates the Prx system, which also supports the floodgate hypothesis. As shown by our results, H2O2 alone was not an efficient oxidant for oxidation of Trx1, but oxidation of Trx1 by H2O2 could be accelerated via Prx1 catalysis. The oxidized Trx1 was then inactive as a substrate for TrxR1, resulting in the breakage of the electron chain from NADPH to Trx1 via TrxR1, and therefore, the oxidized Trx1 was also inactive as a disulfide reductase. Eventually, this would lead to oxidation of Prx1 and local accumulation of H2O2 due to lack of a electron donor, which subsequently resulted in inhibition of protein-tyrosine phosphatases and PTEN.

In our previous study (24), we found that oxidation of Trx1 leads to intracellular reactive oxygen species accumulation and cell death. Reactive oxygen species have been shown to be function as signaling molecules (42). Gitler et al. reported that the transient oxidation of Trx1 increases in parallel with H2O2 formation and the oxidized forms of several cellular proteins (46). Besides the Prx system, the ASK1, NF-κB, p53, Ref-1, and AP-1 pathways would also benefit from the inactivation of Trx1 (7, 47). Fully reduced Trx1 can bind to ASK1 and inhibit its activity, whereas the oxidization of Trx1 results in the activation of ASK1 and the induction of ASK1-dependent apoptosis (48). The same is true for Trxip, i.e. only reduced Trx1 binds to Trxip, which controls the activity of the Trx system and is down-regulated in tumor cells (49–51). In addition, Trx1 is essential for maintaining the DNA binding capacity of certain transcription factors such as NF-κB, Ref-1, and AP-1 by reducing critical Cys residues in the proteins.

In conclusion, reversible oxidation of Trx1 via the non-active site dithiol plays an important role in the transmission of oxidative signals and cellular redox signaling. To understand the precise mechanism of the non-active site cysteine residues of human Trx1 in regulating the redox signaling under oxidative stress, further studies should be carried out. Especially challenging is to explore the role of the reversible inactivation and redox state of Trx1 in the signaling pathway through the cell membrane.

This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (961), the Swedish Research Council Medicine (13X-3529), the K&A Wallenberg Foundation, and grants from Karolinska Institutet.

- Trx

- thioredoxin

- TrxR

- Trx reductase

- Txnip

- Trx-interacting protein

- Prx

- peroxiredoxin

- Grx

- glutaredoxin

- BSO

- buthionine sulfoximine

- IAA

- iodoacetic acid

- IAM

- iodoacetamide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Holmgren A. (1968) Thioredoxin. 6. The amino acid sequence of the protein from Escherichia coli B. Eur. J. Biochem. 6, 475–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holmgren A. (1985) Thioredoxin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 54, 237–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eklund H., Gleason F. K., Holmgren A. (1991) Structural and functional relations among thioredoxins of different species. Proteins 11, 13–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holmgren A., Lu J. (2010) Thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase: current research with special reference to human disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 396, 120–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holmgren A. (2000) Antioxidant function of thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2, 811–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheng Z., Zhang J., Ballou D. P., Williams C. H., Jr. (2011) Reactivity of thioredoxin as a protein thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase. Chem. Rev. 111, 5768–5783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lillig C. H., Holmgren A. (2007) Thioredoxin and related molecules–from biology to health and disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 9, 25–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Niso-Santano M., González-Polo R. A., Bravo-San Pedro J. M., Gómez-Sánchez R., Lastres-Becker I., Ortiz-Ortiz M. A., Soler G., Morán J. M., Cuadrado A., Fuentes J. M., and Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red sobre Enfermedades (CIBERNED) (2010) Activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 is a key factor in paraquat-induced cell death: modulation by the Nrf2/Trx axis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 48, 1370–1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Patwari P., Higgins L. J., Chutkow W. A., Yoshioka J., Lee R. T. (2006) The interaction of thioredoxin with Txnip. Evidence for formation of a mixed disulfide by disulfide exchange. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21884–21891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Masutani H., Yoshihara E., Masaki S., Chen Z., Yodoi J. (2012) Thioredoxin binding protein (TBP)-2/Txnip and α-arrestin proteins in cancer and diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 50, 23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nishiyama A., Matsui M., Iwata S., Hirota K., Masutani H., Nakamura H., Takagi Y., Sono H., Gon Y., Yodoi J. (1999) Identification of thioredoxin-binding protein-2/vitamin D3 up-regulated protein 1 as a negative regulator of thioredoxin function and expression. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21645–21650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hashemy S. I., Holmgren A. (2008) Regulation of the catalytic activity and structure of human thioredoxin 1 via oxidation and S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21890–21898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weichsel A., Gasdaska J. R., Powis G., Montfort W. R. (1996) Crystal structures of reduced, oxidized, and mutated human thioredoxins: evidence for a regulatory homodimer. Structure 4, 735–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Watson W. H., Pohl J., Montfort W. R., Stuchlik O., Reed M. S., Powis G., Jones D. P. (2003) Redox potential of human thioredoxin 1 and identification of a second dithiol/disulfide motif. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33408–33415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Watson W. H., Yang X., Choi Y. E., Jones D. P., Kehrer J. P. (2004) Thioredoxin and its role in toxicology. Toxicol. Sci. 78, 3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holmgren A. (1977) Bovine thioredoxin system. Purification of thioredoxin reductase from calf liver and thymus and studies of its function in disulfide reduction. J. Biol. Chem. 252, 4600–4606 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rhee S. G. (2006) Cell signaling. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science 312, 1882–1883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rhee S. G., Chae H. Z., Kim K. (2005) Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 38, 1543–1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Forman H. J., Maiorino M., Ursini F. (2010) Signaling functions of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry 49, 835–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rhee S. G., Woo H. A., Kil I. S., Bae S. H. (2012) Peroxiredoxin functions as a peroxidase and a regulator and sensor of local peroxides. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 4403–4410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rengby O., Johansson L., Carlson L. A., Serini E., Vlamis-Gardikas A., Kårsnäs P., Arnér E. S. (2004) Assessment of production conditions for efficient use of Escherichia coli in high-yield heterologous recombinant selenoprotein synthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 5159–5167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takahashi N., Hirose M. (1990) Determination of sulfhydryl groups and disulfide bonds in a protein by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 188, 359–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bersani N. A., Merwin J. R., Lopez N. I., Pearson G. D., Merrill G. F. (2002) Protein electrophoretic mobility shift assay to monitor redox state of thioredoxin in cells. Methods Enzymol. 347, 317–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Du Y., Zhang H., Lu J., Holmgren A. (2012) Glutathione and glutaredoxin act as a backup of human thioredoxin reductase 1 to reduce thioredoxin 1 preventing cell death by aurothioglucose. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 38210–38219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dominy C. N., Andrews D. W. (2003) Site-directed mutagenesis by inverse PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 235, 209–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Studier F. W. (2005) Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr. Purif. 41, 207–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kallis G. B., Holmgren A. (1980) Differential reactivity of the functional sulfhydryl groups of cysteine-32 and cysteine-35 present in the reduced form of thioredoxin from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 10261–10265 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhao R., Masayasu H., Holmgren A. (2002) Ebselen: a substrate for human thioredoxin reductase strongly stimulating its hydroperoxide reductase activity and a superfast thioredoxin oxidant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 8579–8584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rothwarf D. M., Scheraga H. A. (1992) Equilibrium and kinetic constants for the thiol-disulfide interchange reaction between glutathione and dithiothreitol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 7944–7948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Østergaard H., Tachibana C., Winther J. R. (2004) Monitoring disulfide bond formation in the eukaryotic cytosol. J. Cell Biol. 166, 337–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gutscher M., Pauleau A. L., Marty L., Brach T., Wabnitz G. H., Samstag Y., Meyer A. J., Dick T. P. (2008) Real-time imaging of the intracellular glutathione redox potential. Nat. Methods 5, 553–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lillig C. H., Berndt C., Holmgren A. (2008) Glutaredoxin systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1780, 1304–1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gelhaye E., Rouhier N., Jacquot J. P. (2003) Evidence for a subgroup of thioredoxin h that requires GSH/Grx for its reduction. FEBS Lett. 555, 443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koh C. S., Navrot N., Didierjean C., Rouhier N., Hirasawa M., Knaff D. B., Wingsle G., Samian R., Jacquot J. P., Corbier C., Gelhaye E. (2008) An atypical catalytic mechanism involving three cysteines of thioredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23062–23072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meng L., Wong J. H., Feldman L. J., Lemaux P. G., Buchanan B. B. (2010) A membrane-associated thioredoxin required for plant growth moves from cell to cell, suggestive of a role in intercellular communication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 3900–3905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Japelaghi R. H., Haddad R., Garoosi G. A. (2012) Isolation, identification and sequence analysis of a thioredoxin h gene, a member of subgroup III of h-type Trxs from grape (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Askari). Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 3683–3693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meyer Y., Belin C., Delorme-Hinoux V., Reichheld J. P., Riondet C. (2012) Thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems in plants: molecular mechanisms, crosstalks, and functional significance. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 17, 1124–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zito E., Melo E. P., Yang Y., Wahlander Å., Neubert T. A., Ron D. (2010) Oxidative protein folding by an endoplasmic reticulum-localized peroxiredoxin. Mol. Cell 40, 787–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tavender T. J., Springate J. J., Bulleid N. J. (2010) Recycling of peroxiredoxin IV provides a novel pathway for disulphide formation in the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 29, 4185–4197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gough D. R., Cotter T. G. (2011) Hydrogen peroxide: a Jekyll and Hyde signalling molecule. Cell Death Dis. 2, e213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Veal E., Day A. (2011) Hydrogen peroxide as a signaling molecule. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 147–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. D'Autréaux B., Toledano M. B. (2007) ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 813–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tonks N. K. (2005) Redox redux: revisiting PTPs and the control of cell signaling. Cell 121, 667–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wood Z. A., Poole L. B., Karplus P. A. (2003) Peroxiredoxin evolution and the regulation of hydrogen peroxide signaling. Science 300, 650–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Woo H. A., Yim S. H., Shin D. H., Kang D., Yu D. Y., Rhee S. G. (2010) Inactivation of peroxiredoxin I by phosphorylation allows localized H2O2 accumulation for cell signaling. Cell 140, 517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gitler C., Zarmi B., Kalef E., Meller R., Zor U., Goldman R. (2002) Calcium-dependent oxidation of thioredoxin during cellular growth initiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290, 624–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lu J., Holmgren A. (2009) Selenoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 723–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Saitoh M., Nishitoh H., Fujii M., Takeda K., Tobiume K., Sawada Y., Kawabata M., Miyazono K., Ichijo H. (1998) Mammalian thioredoxin is a direct inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK) 1. EMBO J. 17, 2596–2606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yoshioka J., Schulze P. C., Cupesi M., Sylvan J. D., MacGillivray C., Gannon J., Huang H., Lee R. T. (2004) Thioredoxin-interacting protein controls cardiac hypertrophy through regulation of thioredoxin activity. Circulation 109, 2581–2586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen J., Saxena G., Mungrue I. N., Lusis A. J., Shalev A. (2008) Thioredoxin-interacting protein: a critical link between glucose toxicity and beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetes 57, 938–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yoshihara E., Chen Z., Matsuo Y., Masutani H., Yodoi J. (2010) Thiol redox transitions by thioredoxin and thioredoxin-binding protein-2 in cell signaling. Methods Enzymol. 474, 67–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]