Background: Elimination of TRAIL resistance by therapeutic agents is an attractive strategy for cancer therapy.

Results: Azadirone can sensitize cancer cells to TRAIL through up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 signaling, down-regulation of cell survival proteins, and up-regulation of proapoptotic proteins.

Conclusion: Azadirone can enhance the efficacy of TRAIL against cancer cells.

Significance: Combinations of azadirone and TRAIL are an effective approach for cancer therapy.

Keywords: Anticancer Drug, Apoptosis, Cancer Therapy, MAP Kinases (MAPKs), Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), Trail, CHOP, Death Receptor, Limonoid

Abstract

Although tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) has shown efficacy in a phase 2 clinical trial, development of resistance to TRAIL by tumor cells is a major roadblock. We investigated whether azadirone, a limonoidal tetranortriterpene, can sensitize human tumor cells to TRAIL. Results indicate that azadirone sensitized cancer cells to TRAIL. The limonoid induced expression of death receptor (DR) 5 and DR4 but did not affect expression of decoy receptors in cancer cells. The induction of DRs was mediated through activation of ERK and through up-regulation of a transcription factor CCAAT enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) as silencing of these signaling molecules abrogated the effect of azadirone. These effects of azadirone were cancer cell-specific. The CHOP binding site on the DR5 gene was required for induction of DR5 by azadirone. Up-regulation of DRs was mediated through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as ROS scavengers reduced the effect of azadirone on ERK activation, CHOP up-regulation, DR induction, and TRAIL sensitization. The induction of DRs by this limonoid was independent of p53, but sensitization to TRAIL was p53-dependent. The limonoid down-regulated the expression of cell survival proteins and up-regulated the proapoptotic proteins. The combination of azadirone with TRAIL was found to be additive at concentrations lower than IC50, whereas at higher concentrations, the combination was synergistic. Overall, this study indicates that azadirone can sensitize cancer cells to TRAIL through ROS-ERK-CHOP-mediated up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 signaling, down-regulation of cell survival proteins, and up-regulation of proapoptotic proteins.

Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)2 preferentially induces apoptosis in cancer cells while exhibiting little or no toxicity in normal cells (1). However, development of resistance to TRAIL by certain cancer types is a major roadblock. Numerous mechanisms have been identified by which tumor cells develop resistance to TRAIL. One potential mechanism for the development of TRAIL resistance involves down-regulation of death receptor (DR) 4 (2) and DR5 (3). A second mechanism of TRAIL resistance involves up-regulation of antagonistic decoy receptors that bind TRAIL but do not contain the functional domains necessary to transduce apoptotic signals (4, 5). A third mechanism of TRAIL resistance is up-regulation in cell survival proteins such as Bcl-xL (6), Bcl-2 (7), XIAP (8), survivin (9), cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein (c-FLIP, a caspase-8 inhibitor also known as I-FLICE) (10), and Mcl-1 (11), and down-regulation in proapoptotic proteins. It is also possible that cancer cells may simultaneously exhibit multiple mechanisms of TRAIL resistance (12). Thus eliminating TRAIL resistance by therapeutic agents is an attractive strategy for cancer therapy.

TRAIL has been shown to induce apoptosis in cancer cells by binding to two transmembrane agonistic receptors (13), DR4 (TRAIL-R1) (14) and DR5 (TRAIL-R2) (15). In addition, TRAIL binds to three antagonistic receptors, decoy receptor 1 (DcR1) and DcR2 (16, 17), and the soluble receptor osteoprotegerin (18). The decoy receptors are without functional death domain, compete with death receptors for TRAIL, and suppress apoptosis (19). The binding of TRAIL to DR5 and DR4 triggers cell death through two apoptotic pathways: the extrinsic pathway and the intrinsic pathway. The signaling initiated by the extrinsic pathway involves recruitment of Fas-associated death domain (FADD) and procaspase-8 in a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) (20). Pro-caspase-8 is then processed into caspase-8 in the death-inducing signaling complex, which in turn induces apoptosis either by direct activation of caspase-3 or through cleavage of Bid to truncated Bid (tBid). The truncated Bid is then translocated to the mitochondria where the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis is initiated.

Numerous signaling molecules are known to trigger DR5 and DR4 induction, including activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and the binding of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) homologous protein (CHOP) transcription factor to DR5 promoter (21). Reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are a byproduct of normal metabolic processes and generated by exogenous sources, are integral components of cell signaling pathways (22). Important downstream mediators of ROS-induced signaling are the MAPKs (23), such as JNK, p38 MAPK, and ERK. ROS have also been shown to induce CHOP expression (24). Thus the agents that can modulate the expression of these signaling molecules can induce DR5 and DR4 expression and might offer potential as anticancer agents. One of the potential sources of such agents includes natural products derived from nature. Natural products have played a significant role in the discovery of cancer drugs over the years; more than 70% of drugs are of natural origin (25). Azadirone, a limonoidal tetranortriterpene originally identified from the oil of the neem tree (Azadirachta indica), could be one such agent (26–28). A. indica belongs to the Meliaceae family, traditionally called “nature's drug store” (29). In east Africa, the tree is known as “Mwarobaini” in Swahili, which literally means “the tree of the 40,” because it is considered as a treatment for 40 different diseases (30, 31). In India, the tree is known as a “village pharmacy” because of its tremendous therapeutic potential.

Although azadirone was identified more than three decades ago, very little is known about the biological activities of this limonoid. The tetranortriterpene has been shown to exhibit antifeedant activity against Mexican bean beetles, Epilachna varivestis (27, 32). The limonoid has also been shown to possess antimalarial activity in in vitro antiplasmodial tests (33). In another study, the limonoid was shown to possess potent anticancer activity against breast cancer, melanoma, and prostate cancer cell lines (34). In Swiss albino mice transplanted with tumor cells, the tetranortriterpene exhibited potent anticancer activity at 75 mg/kg of body weight after 4 days (34). The α,β-unsaturated enone moiety in the A ring of the molecule has been shown to contribute to the anticancer activity of azadirone (34).

To our knowledge, the molecular mechanism by which azadirone exerts anticancer effects has not been reported before. Based on previous studies, we hypothesized that azadirone can sensitize tumor cells to TRAIL by modulating signaling molecules that regulate apoptosis. Results to be discussed indicate that azadirone does sensitize tumor cells to TRAIL through ROS-ERK-CHOP-mediated up-regulation of DR5 and DR4, down-regulation of cell survival proteins, and up-regulation of proapoptotic proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Azadirone (see Fig. 1A) was isolated from A. indica seeds. Powdered seed kernels of A. indica (1 kg) were defatted with hexane and further extracted with acetone at room temperature. The extract (24 g) was then separated by silica gel chromatography (100–200 mesh) by gradient elution with hexane and ethyl acetate mixtures. Fraction pool 7 obtained by elution of the column with hexane-ethyl acetate (9:1, v/v) on crystallization yielded azadirone (132 mg). The structure was confirmed by infrared, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and mass spectral analyses, and the data were compared with findings from other studies (26, 27, 35). A 50 mm solution of this tetranortriterpene was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide and then diluted as needed in cell culture medium. Penicillin, streptomycin, DMEM, RPMI 1640, fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), TRIzol reagent, and kits for the live/dead assay and SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR were purchased from Invitrogen. Soluble recombinant human TRAIL/Apo2Lwas purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Antibodies against CHOP, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, cIAP-1, cIAP-2, Mcl-1, Bid, Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase(PARP), p53, ERK2, phospho-ERK1/2, caspase-3, caspase-8, caspase-9, cytochrome c, p38, JNK1, and phospho-JNK (Thr183/185) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The DR5 antibody was purchased from ProSci, Inc. (Poway, CA), anti-XIAP was from BD Biosciences, and anti-I-FLICE, anti-DR4, anti-DcR1, and anti-DcR2 were from Imgenex (San Diego, CA). An antibody against phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin, N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC), glutathione (GSH), diphenylene iodonium, and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma. Antibodies against survivin- and phycoerythrin-conjugated DR5 and DR4 were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The siRNAs for DR5, DR4, ERK2, and CHOP and the HiPerFect transfection reagent were obtained from Qiagen (Valencia, CA), whereas NOX-1 siRNA was from Dharmacon Thermo Scientific.

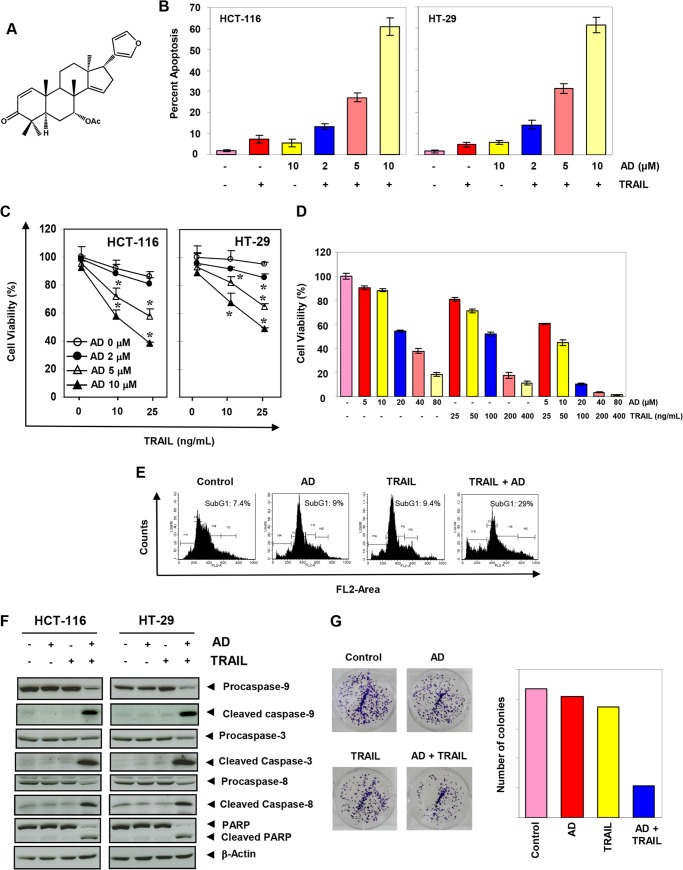

FIGURE 1.

Azadirone sensitizes human cancer cells to TRAIL. A, chemical structure of azadirone. Cells (HCT-116 and HT-29) were treated with the indicated concentrations of azadirone for 6 h, washed with PBS, and then exposed to TRAIL for 24 h. B and C, cell viability was measured by the live/dead assay (B) and by MTT assay (C). AD, azadirone. D, azadirone reduces the viability of HCT116 cells to a greater extent when used in combination with TRAIL. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of azadirone and TRAIL alone or cells were treated first with azadirone for 6 h, washed with PBS, and then exposed to TRAIL for 24 h. Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. E, HCT-116 cells were stained with PI, and the sub-G1 fraction was analyzed by flow cytometry. F, whole-cell extracts from treated cells were analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. G, cells were washed and allowed to form colonies for 14 days. The colonies were then stained with crystal violet and counted. * indicates the significance of difference as compared with control; p < 0.05.

Cell Lines

The human cell lines HCT-116 and HT-29 (colon adenocarcinoma), U-266 (multiple myeloma), A293 (embryonic kidney carcinoma), AsPC-1 (pancreatic adenocarcinoma), MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 (breast adenocarcinoma), and H1299 (lung adenocarcinoma) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The human cell line KBM-5 (chronic myeloid leukemia) was provided by Dr. Nicholas J. Donato of the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center (Ann Arbor, MI). HCT-116 variants with deletion in p53 were supplied by Dr. B. Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University). The HCT-116 variant cells were cultured in McCoy's 5A medium with 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin. KBM-5 cells were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium with 15% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin. MCF-7, HCT-116, A293, and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in DMEM, MCF-10A cells were cultured in mammary epithelial basal medium, and other cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin.

Cytotoxicity Assay

The effects of azadirone on the cytotoxic potential of TRAIL were assessed by measuring mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity using MTT as the substrate (36). The assay is based on the formation of purple formazan dyes that are produced by the cleavage of a tetrazolium ring of MTT by mitochondrial dehydrogenases of viable cells. To examine the synergy between azadirone and TRAIL, cells were treated with azadirone alone (5, 10, 20, 40, 80 μm), TRAIL alone (25, 50, 100, 200, 400 ng/ml), and azadirone in combination with TRAIL at a fixed ratio. Cell viability was examined by MTT assay.

Live/Dead Assay

To measure cell viability, we also used the live/dead assay, which assesses intracellular esterase activity and plasma membrane integrity. It is a two-color fluorescence assay that simultaneously determines the numbers of live cells and dead cells. The assay was performed as described previously (36). Four different microscopic fields were selected to count the number of live and dead cells.

Clonogenic Assay

The clonogenic assay determines the ability of cells in a given population to undergo unlimited division and form colonies. Treated and untreated cells were allowed to form colonies for 14 days and were then stained with 0.3% crystal violet solution (37, 38).

Propidium Iodide (PI) Staining for Sub-G1 Analysis

The sub-G1 population of cells was analyzed by using PI staining as described previously (38). This method is based on the fact that cells undergoing apoptosis will lose part of their DNA (due to DNA fragmentation), and these cells may be detected as a sub-G1 population after PI staining.

Assay for Luciferase Activity

The DR5-luciferase reporter construct containing wild-type and mutant CHOP binding sites has been described before (21). We used a calcium phosphate transfection kit and essentially followed the manufacturer's instructions for transfection (Invitrogen). In brief, A293 cells were co-transfected with 0.05 μg/μl β-galactosidase as a normalization control and 3 μg of firefly luciferase constructs containing the wild-type or mutant DR5 promoter region for 24 h. Cells were then treated with 10 μm azadirone for 24 h, and luciferase activity was measured as described before (39).

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR

TRIzol reagent was used to extract RNA from control and treated cells, and DR5 and DR4 transcripts were detected and amplified with use of the SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR kit (37, 40). PCR products were run on 2% agarose gel and then stained with ethidium bromide. Stained bands were visualized under UV light and photographed.

Transfection with siRNA

We used the HiPerFect transfection reagent for silencing DR5, DR4, ERK2, and CHOP. Cells were plated and allowed to adhere for 24 h. On the day of transfection, 12 μl of transfection reagent was added to 25 nm siRNA in a final volume of 100 μl of culture medium. After 48 h, cells were treated with azadirone and then exposed to TRAIL for 24 h (37, 40).

Western Blot Analysis

The effect of azadirone on protein expression was examined by Western blot analysis. The whole-cell protein extract was prepared and then separated by SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins were electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, probed with relevant antibodies, and detected by an ECL reagent (GE Healthcare (41)).

Assay for Cell Surface Expression of DR5 and DR4

This assay, performed as described previously (38), is based on the fact that phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-DR5 and anti-DR4 bind to cells expressing DR5 and DR4 on their surface, respectively. The cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm.

Measurement of Intracellular ROS

We used membrane-permeable DCFH-DA dye to measure intracellular ROS generation by flow cytometry using membrane-permeable DCFH-DA dye. The assay was conducted according to a previously published protocol (37).

Statistical Analysis

Where indicated, values represent as the mean ± S.D. A two-tailed unpaired Student's t test was carried out for statistical analysis. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Whether the combinations of azadirone and TRAIL are synergistic, additive, or antagonistic was determined statistically by the median effect analysis of Chou-Talalay (42, 43). The analysis yielded point estimates as well as confidence intervals of the interaction index II for a drug dose ratio of 5:1. The values of interaction indices II < 1, II = 1, II > 1 indicated whether the drug interactions were synergistic, additive, or antagonistic, respectively. The analysis was implemented using the statistical software package R.

RESULTS

The goal of this study was to determine whether azadirone can sensitize human cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis and if so, how azadirone mediates such an effect. We used the HCT-116 cell lines for most of the studies because several variants of this cell line are available. In addition, we used HT-29 cells that are relatively resistant to TRAIL. We also used several other cell lines to determine the specificity of the effect of azadirone.

Azadirone Potentiates TRAIL-induced Apoptosis in Human Colon Cancer Cells

We used various assays to examine the effects of azadirone on TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cells. Apoptosis as measured by the live/dead assay indicated that the effect of TRAIL on the viability of cells was minimal. However, when cells were treated with azadirone before TRAIL, the number of apoptotic cells increased in a concentration-dependent manner. More specifically, apoptosis increased from 7.3 to 61% in HCT-116 cells and from 4.8 to 61.4% in HT-29 cells (Fig. 1B).

We also examined the effect of azadirone on cell viability by measuring mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity. Azadirone alone was minimally cytotoxic to HCT-116 and HT-29 cells. Furthermore, HT-29 cells, as compared with HCT-116 cells, were relatively resistant to TRAIL. When cells were pretreated with azadirone, the cytotoxic effects of TRAIL were enhanced in a concentration-dependent manner in both HCT-116 and HT-29 cells (Fig. 1C). Azadirone enhanced the cytotoxic effects of TRAIL at a concentration as low as 5 μm. The IC50 values for azadirone and TRAIL in HCT-116 cells were found to be 28.7 μm and 111.4 ng/ml, respectively. Using the Chou-Talalay method for synergy quantification, we found that the azadirone reduced the viability of HCT116 cells to a greater extent when used in combination with TRAIL (Fig. 1D). Drug interaction index (II) analysis indicated that the effects of combinations on cell viability were additive when azadirone and TRAIL were used at concentrations lower than their IC50 concentrations. However, at concentrations higher than IC50, azadirone and TRAIL combinations were found to be synergistic.

We further examined the effects of azadirone on TRAIL-induced apoptosis by measuring a sub-G1 population using PI staining. Results indicated that apoptosis was induced at 9% by azadirone, at 9.4% by TRAIL, and at 29% by the combination of the two agents. These results again indicated an enhancement of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by azadirone (Fig. 1E).

One of the hallmarks of apoptosis is the activation of caspases that precede PARP cleavage. We examined the effect of azadirone on caspase activation and PARP cleavage in colon cancer cells. Although TRAIL alone had little effect, pretreatment of cells with azadirone was associated with an increase in caspase activation and subsequent PARP cleavage (Fig. 1F). These results suggest that azadirone increases the apoptotic potential of TRAIL in colon cancer cells through both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways.

We also examined the effect of azadirone on TRAIL-induced suppression of long term colony formation by colon cancer cells. Azadirone and TRAIL alone were minimally effective in reducing the colony-forming ability of colon cancer cells. However, when cells were treated with azadirone before TRAIL, the colony-forming ability of tumor cells was significantly reduced (Fig. 1G).

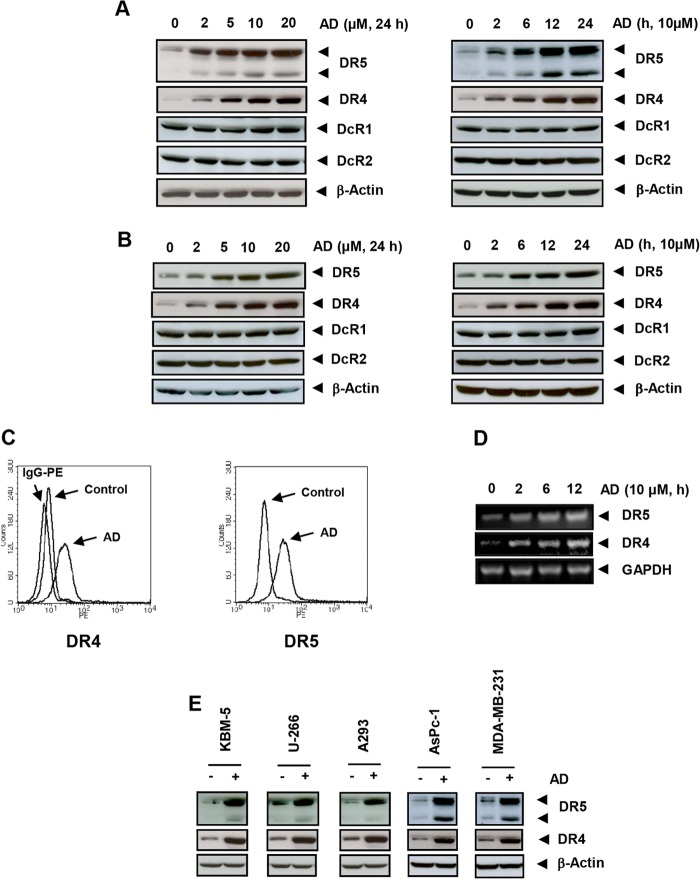

Azadirone Induces Expression of TRAIL Receptors DR5 and DR4

Whether azadirone has the potential to induce expression of TRAIL receptors in cancer cells was investigated. The limonoid induced DR5 and DR4 expression in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells in a concentration-dependent (Fig. 2, A and B, left panel) and time-dependent (Fig. 2, A and B, right panel) manner. Results indicated that treatment of cells with 10 μm azadirone for 24 h was optimal for up-regulating DR5 and DR4 without affecting cell viability. However, the expression of DcR1 and DcR2 was not affected by azadirone treatment.

FIGURE 2.

Azadirone induces DR5 and DR4 expression but does not affect DcR1 or DcR2 expression in cancer cells. A and B, human cancer cells HCT-116 (A) and HT-29 (B) were treated with the indicated concentrations of azadirone (AD) for 24 h (left panel) or with 10 μm azadirone for the indicated time (right panel). Whole-cell protein extracts were analyzed for expression of DR5 and DR4 by Western blotting. C, azadirone enhances cell surface expression of DR5 and DR4. Cells were treated with 10 μm azadirone for 24 h, and cell surface expression of DR5 and DR4 was measured using phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated DR5 and DR4 antibodies by flow cytometry. D, azadirone up-regulates DR5 and DR4 expression at the RNA level. Cells were treated with 10 μm azadirone for the indicated times. Total RNA was extracted and examined for DR5 and DR4 mRNA by RT-PCR. GAPDH was used as an internal control. E, azadirone-induced up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 is not cell type-specific. Human chronic myeloid leukemia (KBM-5), multiple myeloma (U-266), embryonic kidney cancer (A293), pancreatic cancer (AsPc-1), and breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) cells were treated with 10 μm azadirone for 24 h. The whole-cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using DR5 and DR4 antibodies.

Whether azadirone induces expression of DR5 and DR4 on the cell surface was also investigated by flow cytometry. We found that azadirone increased the expression of DR5 and DR4 on the cell surface (Fig. 2C).

Whether azadirone induces up-regulation in DR5 and DR4 expression at the transcription level was investigated. We found that azadirone induced DR5 and DR4 mRNA transcription in HCT-116 cells (Fig. 2D). The induction in DR5 and DR4 transcription was found as early as 2 h after azadirone treatment.

We also investigated whether the up-regulation in DR5 and DR4 expression by triterpene is specific to colon cancer cells. We treated different cancer types with azadirone and analyzed expression of DR5 and DR4 by Western blotting. Azadirone was found to induce DR5 and DR4 expression in chronic myeloid leukemia (KBM-5), multiple myeloma (U-266), embryonic kidney carcinoma (A293), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (AsPC-1), and breast adenocarcinoma (MDA-MB-231) cells (Fig. 2E). Overall, these results suggest that the up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 by azadirone is not cell type-specific.

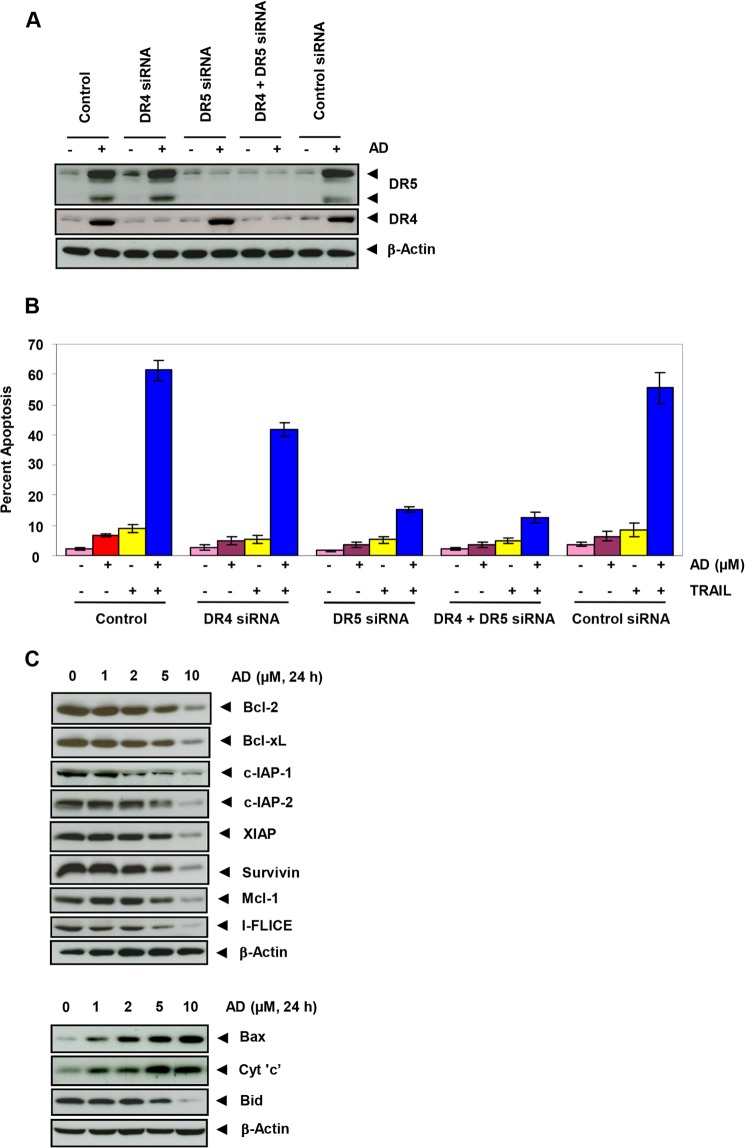

Induction of DR5 and DR4 by Azadirone Is Required for Sensitization of TRAIL-induced Apoptosis

Whether up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 by azadirone is essential to sensitize tumor cells to TRAIL was investigated. DR5 and DR4 in HCT-116 cells were silenced by specific siRNAs and then exposed to azadirone and TRAIL. As expected, azadirone was unable to induce DR5 and DR4 after gene silencing of DR5 and DR4, respectively (Fig. 3A). DR5 siRNA had no effect on azadirone-induced DR4 expression. Similarly, DR4 siRNA did not affect azadirone-induced DR5 up-regulation.

FIGURE 3.

Gene silencing of DR5 and DR4 abrogates the ability of azadirone to enhance TRAIL-induced apoptosis in cancer cells. A, human cancer cells were transfected with DR5 siRNA and DR4 siRNA, alone or in combination, and control siRNA. After 48 h, cells were treated with 10 μm azadirone (AD) for 24 h, and whole-cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using DR5 and DR4 antibodies. B, after transfection, cells were treated with 10 μm azadirone for 6 h and then incubated with TRAIL (25 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cell viability was measured by the live/dead assay. C, azadirone down-regulates antiapoptotic (top) and proapoptotic (bottom) protein expression in colon cancer cells. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of azadirone for 24 h. Whole-cell protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Cyt 'c', cytochrome c.

Next, we examined whether silencing of DR5 or DR4 by siRNA could also abrogate the sensitizing effects of azadirone on TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Azadirone was unable to potentiate TRAIL-induced apoptosis in HCT-116 cells after DR5 gene silencing. However, the effect of DR4 silencing on TRAIL-induced apoptosis was lower in comparison with that observed after DR5 silencing. Control siRNA had no effect on potentiation of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by azadirone (Fig. 3B).

Azadirone Suppresses Expression of Cell Survival Proteins

We next examined whether azadirone has the potential to modulate expression of cell survival proteins in colon cancer cells. Expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, c-IAP-1, c-IAP-2, XIAP, survivin, Mcl-1, and I-FLICE was suppressed in a concentration-dependent manner by azadirone treatment in HCT-116 cells (Fig. 3C, upper panel). The effect of azadirone on the expression of cell survival proteins was more prominent at 5 and 10 μm. These results suggest that azadirone has the potential to suppress expression of cell survival proteins.

Azadirone Induces Expression of Proapoptotic Proteins

Whether azadirone can modulate the expression of proapoptotic proteins was also investigated. The limonoid induced the expression of Bax and cytochrome c in a concentration-dependent manner in HCT-116 cells (Fig. 3C, lower panel). The proapoptotic protein Bid, which is cleaved by caspase-8 to truncated Bid, was decreased in a concentration-dependent manner by the triterpene treatment. These results suggest that azadirone can up-regulate the expression of proapoptotic proteins.

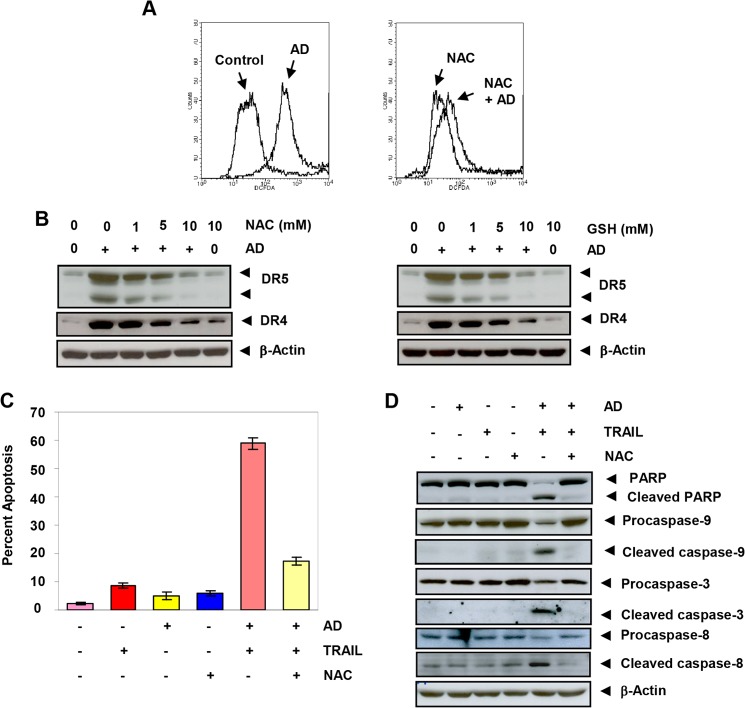

ROS Are Required for Up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 by Azadirone

Because ROS have been implicated in the induction of DR5 and DR4, we investigated whether azadirone-induced up-regulation of death receptors requires ROS. First, we investigated whether this triterpene can induce ROS generation in colon cancer cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, an 8-fold increase in ROS generation was observed by the limonoid treatment in colon cancer cells. Second, we investigated whether azadirone-induced ROS generation could be abrogated by the ROS scavenger NAC. As expected, azadirone-induced ROS generation was almost completely suppressed when cells were pretreated with NAC.

FIGURE 4.

Azadirone up-regulates DR5 and DR4 through mediation of ROS. A, HCT-116 cells were pre-exposed to NAC for 1 h, washed off, labeled with DCFH-DA, and then exposed to azadirone (AD) for 1 h. The intracellular ROS levels were then measured by flow cytometry. B, HCT-116 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of NAC or GSH for 1 h and then treated with 10 μm azadirone for 24 h. The whole-cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using DR5 and DR4 antibodies. C and D, treatment of cells with NAC suppresses apoptosis induced by azadirone plus TRAIL in human cancer cells. Cells were pretreated with NAC for 1 h, washed off, treated with 10 μm azadirone for 6 h, washed off, and then treated with TRAIL for 24 h. C, apoptosis was measured by the live/dead assay in HCT-116 cells. D, whole-cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies.

To examine the role of ROS in azadirone-induced up-regulation of DR5 and DR4, we pretreated HCT-116 cells with ROS scavengers NAC and GSH before azadirone and then examined the expression of DR5 and DR4. Azadirone-induced DR5 and DR4 expression was suppressed by NAC in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4B, left panel). GSH also decreased azadirone-induced DR5 and DR4 expression in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4B, right panel). Overall, these results suggest that triterpene-induced ROS generation is required for up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 in colon cancer cells.

Next, we examined the role of ROS in potentiation of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by azadirone. Cells were treated with NAC before azadirone and TRAIL treatment, and apoptosis was measured with the use of the live/dead assay, PARP cleavage, and caspase activity. As shown in Fig. 4C, the number of apoptotic cells induced by azadirone plus TRAIL was reduced from 59 to 17.3% when cells were pretreated with NAC. Furthermore, the increase in caspase activity and PARP cleavage induced by azadirone plus TRAIL was almost completely reversed when cells were pretreated with NAC (Fig. 4D). Overall, these results suggest that ROS play a critical role in potentiation of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by azadirone.

Activation of MAPK Is Required for Up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 by Azadirone

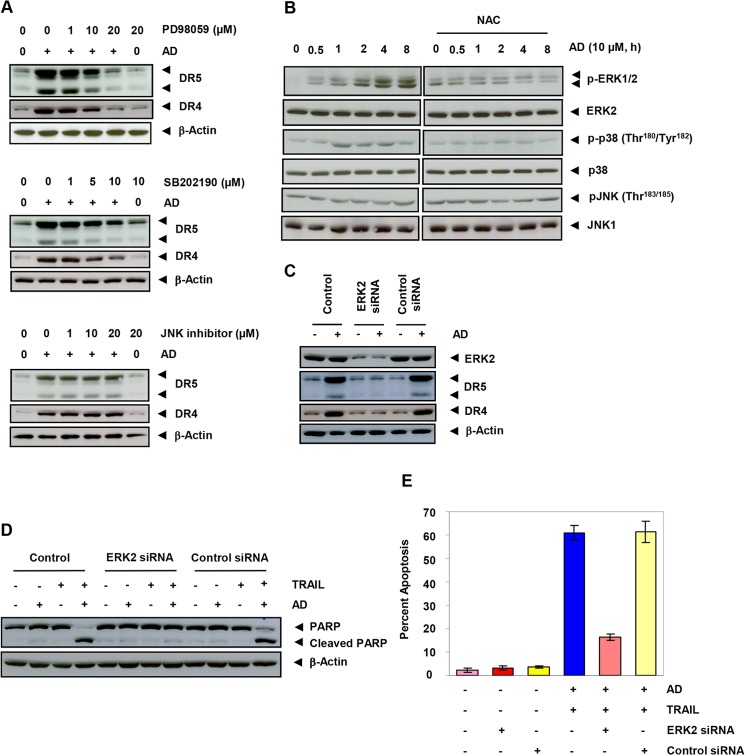

Because MAPKs are involved in the regulation of death receptors, we investigated whether azadirone induces death receptors through MAPK activation. We pretreated cells with pharmacological inhibitors of MAPKs before azadirone and then examined the expression of DR5 and DR4 by Western blotting. The ERK inhibitor (PD98059) suppressed azadirone-induced up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5A, upper panel). The p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB202190) also suppressed azadirone-induced DR5 and DR4 expression in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5A, middle panel). However, the JNK inhibitor was unable to affect azadirone-induced DR5 and DR4 expression (Fig. 5A, lower panel). These observations indicate that MAPKs play a role in azadirone-induced DR5 and DR4 expression.

FIGURE 5.

Azadirone up-regulates DR5 and DR4 in human cancer cells through the ROS-dependent MAPK pathway. A, cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of ERK inhibitor (PD98059), p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB202190), and a JNK inhibitor for 1 h and then treated with 10 μm azadirone (AD) for 24 h. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using DR5 and DR4 antibodies. B, azadirone-induced ERK activation was mediated through ROS. Cells were treated with NAC for 1 h and then exposed to 10 μm azadirone for the indicated times. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. p-ERK1/2, phospho-ERK1/2; p-p38, phospho-p38; pJNK, phospho-JNK. C, gene silencing of ERK abrogates azadirone-induced DR5 and DR4 expression. Cells were transfected with ERK2 siRNA or control siRNA for 48 h and then treated with 10 μm azadirone for 24 h. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using DR5 and DR4 antibodies. D and E, ERK2-transfected cells were treated with 10 μm azadirone for 6 h and then with TRAIL for 24 h. Apoptosis was measured by PARP cleavage or by the live/dead assay.

Because MAPK inhibitors abrogated the expression of DR5 and DR4, we investigated whether azadirone has the potential to activate MAPKs. Cells were treated with azadirone from 0.5 to 8 h, and then activation of ERK, p38, and JNK was investigated. We found that azadirone induced ERK1/2 and p38 in a time-dependent manner. However, p38 activation was subtle and transitory, and azadirone was unable to activate JNK (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that MAPKs, in particular ERK, may play a role in azadirone-induced up-regulation of DR5 and DR4.

Because ROS are implicated in the activation of MAPK (38, 44) and because azadirone induced ROS, we investigated whether azadirone-induced activation of MAPK is ROS-dependent. Cells were treated with NAC for 1 h before treatment with azadirone for 0.5–8 h. The treatment of cells with NAC abolished azadirone-induced activation of ERK (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that azadirone-induced ERK activation is mediated through ROS generation.

To further confirm the role of ERK in azadirone-induced up-regulation of DR5 and DR4, we silenced ERK2 by specific siRNA before triterpene treatment. Results indicated that the triterpene was unable to induce DR5 and DR4 in colon cancer cells when ERK2 was silenced (Fig. 5C).

ERK Is Required for Potentiation of TRAIL-induced Apoptosis by Azadirone

Whether ERK is required for potentiation of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by azadirone was investigated. As shown in Fig. 5D, silencing of ERK2 almost completely suppressed PARP cleavage induced by azadirone and TRAIL. Similarly, the percentage of apoptotic cells was decreased from 60.8 to 16.4% after ERK2 silencing (Fig. 5E). However, control siRNA had no effect on apoptosis induced by azadirone and TRAIL.

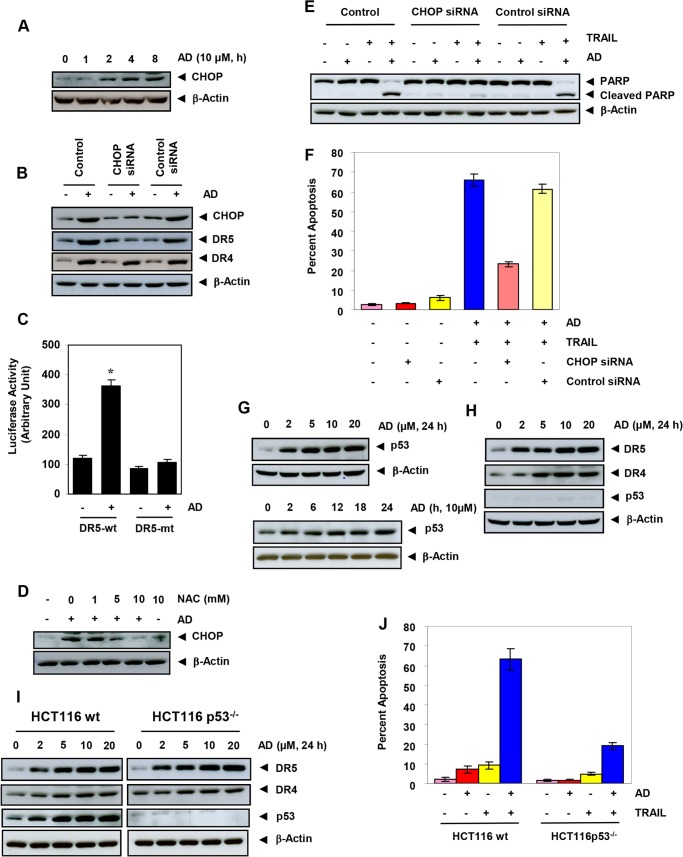

Azadirone-induced Up-regulation of DR5 Is Mediated through Induction of CHOP

Because CHOP is involved in the induction of DR5, we investigated whether this transcription factor is involved in the induction of DR5 by azadirone. First, we investigated whether the triterpene can induce CHOP in HCT-116 cells. The triterpene up-regulated CHOP in HCT-116 cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 6A). Maximum induction in CHOP expression was observed when cells were treated with 10 μm azadirone for 8 h. Second, we silenced CHOP by specific siRNA before treatment with azadirone. We found that azadirone-induced DR5 expression was completely suppressed after CHOP silencing. However, CHOP silencing did not affect DR4 expression (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that CHOP is involved in the induction of DR5 by azadirone.

FIGURE 6.

Azadirone induces DR5 in human cancer cells through ROS-dependent CHOP up-regulation. A, cells were treated with 10 μm azadirone for the indicated times, and whole-cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using CHOP antibody. AD, azadirone. B, gene silencing of CHOP abrogates azadirone-induced DR5 expression in HCT-116 cells. Cells were transfected with CHOP siRNA or control siRNA for 48 h and then treated with 10 μm azadirone for 24 h. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using DR5 and DR4 antibodies. C, mutation of the CHOP binding site on DR5 promoter abolishes azadirone-induced DR5 luciferase activity. A293 cells were transfected with a DR5-luciferase plasmid containing wild-type (wt) or mutated (mt) CHOP binding site for 24 h. Cells were then treated with azadirone, and luciferase activity was determined as described under ”Experimental Procedures.“ D, azadirone-induced CHOP expression is mediated through ROS. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of NAC for 1 h, washed off, and then exposed to 10 μm azadirone for 8 h. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using CHOP antibody. E and F, gene silencing of CHOP abolished apoptosis induced by azadirone plus TRAIL in HCT-116 cells. CHOP-transfected cells were treated with 10 μm azadirone for 6 h and then with TRAIL for 24 h. Apoptosis was measured by PARP cleavage or the live/dead assay. G--J, p53 is required for potentiation of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by azadirone but is not essential for up-regulation of DR5 and DR4. G, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of azadirone for 24 h (upper panel) or with 10 μm azadirone for indicated times (lower panel). Whole-cell protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using p53 antibody. H and I, whole-cell extracts from control and azadirone-treated H1299 (H) and wt and p53−/−HCT-116 (I) cells were analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. J, the wt or p53−/−cells were treated with 10 μm azadirone for 6 h and then exposed to TRAIL for 24 h. Cell viability was measured by the live/dead assay.

To confirm the role of CHOP in azadirone-induced DR5 expression, we performed a mutational study. A293 cells were transfected with DR5-luciferase reporter plasmids containing wild-type or mutant CHOP binding sites and then treated with azadirone. As shown in Fig. 6C, the wild-type DR5 reporter construct revealed enhanced luciferase activity in cells treated with azadirone. However, in cells transfected with mutant plasmid, azadirone was unable to induce luciferase activity.

Whether ROS are implicated in azadirone-induced CHOP up-regulation was investigated. Cells were treated with NAC before treatment with azadirone, and expression of CHOP was examined by Western blotting. We found that treatment with NAC suppressed azadirone-induced CHOP expression in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that ROS are implicated in azadirone-induced up-regulation of CHOP.

CHOP Is Essential for Potentiation of TRAIL-induced Apoptosis by Azadirone

Next, we examined whether CHOP is essential for potentiation of TRAIL-induced apoptosis. We silenced CHOP by specific siRNA before treatment with azadirone and TRAIL. Results indicated that PARP cleavage induced by azadirone plus TRAIL was completely suppressed after CHOP silencing (Fig. 6E). The percentage of apoptotic cells was also reduced from 66.2 to 23.3% after CHOP silencing (Fig. 6F). These results suggest that CHOP is involved in the sensitization of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by azadirone in HCT-116 cells.

p53 Is Not Required for DR5 and DR4 Expression but Is Indispensable for Potentiation of TRAIL-induced Apoptosis by Azadirone

Because p53 has been reported to induce TRAIL receptors, we investigated whether this tumor suppressor is required for the induction of DR5 and DR4 by azadirone. We first examined the potential of azadirone to modulate p53 expression in HCT-116 cells. Azadirone was found to induce p53 in HCT-116 cells in a concentration-dependent (Fig. 6G, upper panel) and time-dependent manner (Fig. 6G, lower panel). Next, we examined whether azadirone-induced p53 is required for DR5 and DR4 expression. We treated p53-deficient H1299 lung adenocarcinoma cells and p53−/− HCT-116 cells with different concentrations of the triterpene. Western blot analysis showed that azadirone induced DR5 and DR4 in these cell types, indicating that p53 is not required for the induction of death receptors by azadirone (Fig. 6, H and I).

Finally, we examined whether p53 plays a role in sensitization of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by azadirone. Results indicated that apoptosis induced by azadirone plus TRAIL was significantly reduced in p53−/− HCT-116 cells. More specifically, apoptosis was reduced from 63.3 to 19% in p53−/− cells (Fig. 6J). Overall, these observations indicate that p53 is required for sensitization of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by azadirone.

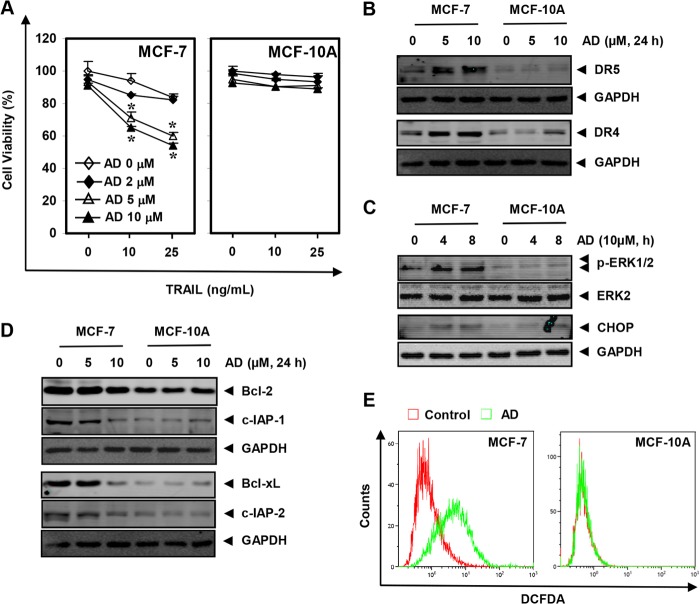

Azadirone Does Not Sensitize Normal Cells to TRAIL

Whether the effects of azadirone were cancer cell-specific was investigated. The normal breast cells (MCF-10A) and breast cancer cells (MCF-7) were first treated with azadirone for 6 h and then with TRAIL for 24 h, and cell viability was examined. Although combinations of azadirone and TRAIL reduced the viability of MCF-7 cells, MCF-10A cells were resistant to azadirone and TRAIL combinations (Fig. 7A). Next, we examined the potential of azadirone in inducing DR5 and DR4 in MCF-7 and MCF-10A cells. Cells were treated with 5 and 10 μm azadirone for 24 h, and whole-cell extract was examined for DR5 and DR4 expression. A concentration-dependent induction of DR5 and DR4 was observed in MCF-7 cells, whereas azadirone was unable to induce these receptors in MCF-10A cells (Fig. 7B). Similarly, activation in ERK and CHOP induction by azadirone were observed in MCF-7 cells but not in MCF-10A cells (Fig. 7C). We also investigated the potential of azadirone in modulating expression of cell survival proteins in MCF-10A cells. First, as compared with MCF-10A, MCF-7 cells expressed relatively high levels of cell survival proteins such as Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, c-IAP-1, and c-IAP-2 (Fig. 7D). Second, the expression of these proteins was suppressed by azadirone in a concentration-dependent manner only in MCF-7 cells. Finally, we determined whether generation of ROS by azadirone is cancer cell-specific. MCF-7 and MCF-10A cells were labeled with DCFH-DA and exposed to 10 μm azadirone for 1 h, and the intracellular ROS levels were then measured by flow cytometry. Results indicated that the basal level of ROS in MCF-7 cells was more as compared with MCF-10A cells. Furthermore, azadirone induced the level of ROS generation by 4.68-fold in MCF-7 cells but did not affect the level of ROS generation in MCF-10A cells (Fig. 7E). Overall, these results suggest that the effects of azadirone may be cancer cell-specific.

FIGURE 7.

Azadirone neither induced death receptors nor modulated expression of cell survival proteins in normal cells. A, MCF-7 and MCF-10A cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of azadirone (AD) for 6 h, washed with PBS, and then exposed to TRAIL for 24 h. Cell viability was assessed by the MTT assay. B–D, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of azadirone for 24 h or with 10 μm azadirone for the indicated times. The whole-cell extracts were analyzed using the indicated antibodies by Western blotting. p-ERK1/2, phospho-ERK1/2. E, azadirone generate ROS in cancer cells but not in normal cells. MCF-7 and MCF-10A cells were labeled with DCFH-DA and exposed to azadirone for 1 h. The intracellular ROS levels were then measured by flow cytometry. * indicates the significance of difference as compared with control; p < 0.05.

Azadirone-induced ROS Generation in MCF-7 Cells Is Mediated through NADPH Oxidase (NOX)

Because azadirone induced ROS generation in breast cancer cells, we sought to investigate the intracellular source of ROS. A plausible source of intracellular ROS generation is NOX complex in cell membranes. We pretreated the cells with 20 μm diphenylene iodonium, a NOX inhibitor, before labeling with DCFH-DA and treatment with azadirone. Results indicated that azadirone-induced ROS generation was reduced from 4.68- to 1.03-fold. Because NOX-1 isoform of NOX complex is expressed in both MCF-7 and HCT-116 cells (data not shown), we sought to determine the possibility of involvement of NOX1 in azadirone-induced ROS generation in MCF-7 cells. We silenced NOX-1 in MCF-7 cells by specific siRNAs before exposing them to azadirone. Results indicated that azadirone-induced ROS generation was reduced from 3.50- to 1.3-fold when cells were transfected with NOX-1 siRNA. However, azadirone-induced ROS generation was unaffected by control siRNA.

DISCUSSION

Although TRAIL is one of the potent cytokines with the potential to kill cancer cells selectively, its use has limitations because of the resistance that certain cancer types develop. Therefore, agents that are safe and can sensitize cancer cells to TRAIL are needed. Here we provide evidence that azadirone, a limonoid triterpene, can sensitize human colon cancer cells to TRAIL. We explored the molecular mechanism by which azadirone sensitizes human cancer cells to TRAIL.

We found that azadirone down-regulated the expression of cell survival proteins including Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, c-IAP-1, c-IAP-2, XIAP, survivin, Mcl-1, and c-FLIP. Because overexpression of these proteins has been shown to contribute to TRAIL resistance in tumor cells (9, 45, 46), it is likely that the sensitization of tumor cells to TRAIL is due to down-regulation in the expression of cell survival proteins by azadirone. In agreement with our observations, previous studies have shown that triterpenes such as nimbolide (37), celastrol (40), and 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid (CDDO) (47) can sensitize tumor cells to TRAIL by suppressing expression of cell survival proteins. XIAP, a potent inhibitor of caspase-3 activity, has previously been shown to confer resistance to TRAIL (48). Enhancement in caspase-3 activity, as observed in the present study, could be due to reduced expression of XIAP. Similarly, enhancement in caspase-8 activity could be due to down-regulation in the expression of its inhibitor, c-FLIP (10). Rosiglitazone, an agonist for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ, has also been shown to sensitize renal cancer cells to TRAIL by down-regulating expression of c-FLIP (49).

We also found that azadirone up-regulated the expression of proapoptotic protein Bax in human colon cancer cells. A previous study showed that the mutational inactivation of Bax leads to development of resistance to TRAIL (50). Thus the sensitization of colon cancer cells to TRAIL could be due to up-regulation of Bax as well. The fact that the limonoid has the potential to activate caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9 suggests that the limonoid induces apoptosis by both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways.

We found that the tetranortriterpene induces DR5 and DR4 but maintains expression of DcR1 and DcR2 in colon cancer cells. We also found that induction of DR5 and DR4 by azadirone was at the transcription level, was not cancer type-specific, and was crucial for sensitization of cancer cells to TRAIL because gene silencing of either receptor significantly suppressed the effect of azadirone in TRAIL-induced apoptosis. We also found that DR5, unlike DR4, was critical to sensitize tumor cells to TRAIL, which might be due to the higher affinity of this cytokine for DR5, as reported previously (51).

We investigated the molecular mechanism by which azadirone induces DR5 and DR4 in colon cancer cells and found that this is accomplished through activation of ERK. In agreement with these observations, a previous study demonstrated the essential role of ERK in inducing DRs by zerumbone (38). Our observations further revealed that induction of DR5 by the limonoid is mediated through CHOP up-regulation. These observations are supported by previous studies showing that induction of DR5 requires binding of CHOP to DR5 promoter (21, 52). The fact that the limonoid was unable to induce DR5 reporter activity in cells transfected with DR5 promoter plasmid containing the mutated CHOP binding site further confirms the role of CHOP in DR5 induction.

We found that one of the most important upstream signals required for the up-regulation of death receptors is ROS. First, this triterpene induced the generation of ROS in cancer cells. Second, use of ROS scavengers down-regulated the expression of death receptors induced by azadirone. Third, ROS scavengers also inactivated MAPKs and down-regulated CHOP. Fourth, potentiation of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by azadirone was also abrogated by the use of ROS scavengers. Indeed, the analysis of the kinetics of ROS generation, MAPK activation, CHOP induction, and DR5 and DR4 up-regulation on azadirone treatment revealed that ROS generation occurred earlier (after 1 h) than did ERK activation (2 h), CHOP induction (2 h), or DR5 and DR4 up-regulation (6 h). Thus ROS generation is an upstream event that leads to MAPK activation, in particular ERK activation and CHOP induction, which in turn are responsible for the increased up-regulation of TRAIL receptors. These observations are supported by earlier studies showing the role of ROS in up-regulating DRs and enhancing the effects of TRAIL by nimbolide (37) and celastrol (40). That the azadirone was unable to modulate DR5, DR4, ERK, and CHOP and did not sensitize normal breast cells to TRAIL suggests its specificity to cancer cells. Although our observations indicated that the azadirone-induced ROS generation was mediated through NOX-1, the possibility of other sources such as mitochondria, peroxisomes, and endoplasmic reticulum cannot be ruled out. How azadirone selectively targets cancer cells remains to be investigated.

We found that the tetranortriterpene also up-regulated p53 in colon cancer cells. However, p53 was not required for azadirone-induced up-regulation of death receptors. In contrast to these observations, a previous study demonstrated the essential role of p53 in inducing DR5 in cancer cells (53). It is likely that the p53-induced up-regulation of DRs depends on the cell type and the nature of the stimulus. The fact that the effect of azadirone on TRAIL was abolished in p53−/− cancer cells indicates that p53 is required for sensitizing tumor cells to TRAIL. Many cancer cells with mutations in p53 are resistant to apoptosis induction (54). We found that the combined treatment of TRAIL with azadirone induced apoptosis not only in cancer cells with wild-type p53 (HCT-116), but also in those with mutant p53 (HT-29, MDA-MB-231). These observations suggest that combined treatment of TRAIL with azadirone is useful for cancer cells with compromised p53 function.

In summary, this study provides evidence for the sensitization of tumor cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through ROS-, ERK-, and CHOP-mediated up-regulation of DR5 and DR4 by azadirone. This study also provides evidence for the down-regulation of cell survival proteins and for the up-regulation of proapoptotic proteins by azadirone. This study suggests that the combinations of azadirone and TRAIL are an effective approach for anticancer therapy. Future studies using clinically relevant animal models, however, are needed to fully realize the potential of this fascinating molecule in the prevention and treatment of cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tamara Locke from the Department of Scientific Publications for carefully proofreading the manuscript. We thank Dr. Riten Mitra for help with analysis of drug interaction data.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Program Project Grant CA124787-01A2. This work was also supported by a grant from the Malaysian Palm Oil Board.

- TRAIL

- tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- DR

- death receptor

- DcR

- decoy receptor

- FLICE

- FADD-like interleukin-1 β-converting enzyme

- FADD

- Fas-associated death domain

- c-FLIP

- cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- CHOP

- C/EBP homologous protein

- C/EBP

- CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein

- XIAP

- X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

- c-IAP

- cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- NOX

- NADPH oxidase

- Bax

- Bcl-2-associated X protein

- DCFH-DA

- 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein-diacetate

- NAC

- N-acetyl-l-cysteine

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- PI

- propidium iodide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ashkenazi A., Pai R. C., Fong S., Leung S., Lawrence D. A., Marsters S. A., Blackie C., Chang L., McMurtrey A. E., Hebert A., DeForge L., Koumenis I. L., Lewis D., Harris L., Bussiere J., Koeppen H., Shahrokh Z., Schwall R. H. (1999) Safety and antitumor activity of recombinant soluble Apo2 ligand. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 155–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kurbanov B. M., Fecker L. F., Geilen C. C., Sterry W., Eberle J. (2007) Resistance of melanoma cells to TRAIL does not result from upregulation of antiapoptotic proteins by NF-κB but is related to downregulation of initiator caspases and DR4. Oncogene 26, 3364–3377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Geelen C. M., Pennarun B., Le P. T., de Vries E. G., de Jong S. (2011) Modulation of TRAIL resistance in colon carcinoma cells: different contributions of DR4 and DR5. BMC Cancer 11, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bouralexis S., Findlay D. M., Atkins G. J., Labrinidis A., Hay S., Evdokiou A. (2003) Progressive resistance of BTK-143 osteosarcoma cells to Apo2L/TRAIL-induced apoptosis is mediated by acquisition of DcR2/TRAIL-R4 expression: resensitisation with chemotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 89, 206–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sheridan J. P., Marsters S. A., Pitti R. M., Gurney A., Skubatch M., Baldwin D., Ramakrishnan L., Gray C. L., Baker K., Wood W. I., Goddard A. D., Godowski P., Ashkenazi A. (1997) Control of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by a family of signaling and decoy receptors. Science 277, 818–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Song J. J., An J. Y., Kwon Y. T., Lee Y. J. (2007) Evidence for two modes of development of acquired tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand resistance: Involvement of Bcl-xL. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 319–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sivaprasad U., Shankar E., Basu A. (2007) Downregulation of Bid is associated with PKCϵ-mediated TRAIL resistance. Cell Death Differ. 14, 851–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schimmer A. D., Welsh K., Pinilla C., Wang Z., Krajewska M., Bonneau M. J., Pedersen I. M., Kitada S., Scott F. L., Bailly-Maitre B., Glinsky G., Scudiero D., Sausville E., Salvesen G., Nefzi A., Ostresh J. M., Houghten R. A., Reed J. C. (2004) Small-molecule antagonists of apoptosis suppressor XIAP exhibit broad antitumor activity. Cancer Cell 5, 25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chawla-Sarkar M., Bae S. I., Reu F. J., Jacobs B. S., Lindner D. J., Borden E. C. (2004) Downregulation of Bcl-2, FLIP or IAPs (XIAP and survivin) by siRNAs sensitizes resistant melanoma cells to Apo2L/TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 11, 915–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Irmler M., Thome M., Hahne M., Schneider P., Hofmann K., Steiner V., Bodmer J. L., Schröter M., Burns K., Mattmann C., Rimoldi D., French L. E., Tschopp J. (1997) Inhibition of death receptor signals by cellular FLIP. Nature 388, 190–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kobayashi S., Werneburg N. W., Bronk S. F., Kaufmann S. H., Gores G. J. (2005) Interleukin-6 contributes to Mcl-1 up-regulation and TRAIL resistance via an Akt-signaling pathway in cholangiocarcinoma cells. Gastroenterology 128, 2054–2065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ndozangue-Touriguine O., Sebbagh M., Mérino D., Micheau O., Bertoglio J., Bréard J. (2008) A mitochondrial block and expression of XIAP lead to resistance to TRAIL-induced apoptosis during progression to metastasis of a colon carcinoma. Oncogene 27, 6012–6022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aggarwal B. B., Gupta S. C., Kim J. H. (2012) Historical perspectives on tumor necrosis factor and its superfamily: 25 years later, a golden journey. Blood 119, 651–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pan G., Ni J., Wei Y. F., Yu G., Gentz R., Dixit V. M. (1997) An antagonist decoy receptor and a death domain-containing receptor for TRAIL. Science 277, 815–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walczak H., Degli-Esposti M. A., Johnson R. S., Smolak P. J., Waugh J. Y., Boiani N., Timour M. S., Gerhart M. J., Schooley K. A., Smith C. A., Goodwin R. G., Rauch C. T. (1997) TRAIL-R2: a novel apoptosis-mediating receptor for TRAIL. EMBO J. 16, 5386–5397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Degli-Esposti M. A., Dougall W. C., Smolak P. J., Waugh J. Y., Smith C. A., Goodwin R. G. (1997) The novel receptor TRAIL-R4 induces NF-κB and protects against TRAIL-mediated apoptosis, yet retains an incomplete death domain. Immunity 7, 813–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Degli-Esposti M. A., Smolak P. J., Walczak H., Waugh J., Huang C. P., DuBose R. F., Goodwin R. G., Smith C. A. (1997) Cloning and characterization of TRAIL-R3, a novel member of the emerging TRAIL receptor family. J. Exp. Med. 186, 1165–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Emery J. G., McDonnell P., Burke M. B., Deen K. C., Lyn S., Silverman C., Dul E., Appelbaum E. R., Eichman C., DiPrinzio R., Dodds R. A., James I. E., Rosenberg M., Lee J. C., Young P. R. (1998) Osteoprotegerin is a receptor for the cytotoxic ligand TRAIL. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 14363–14367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Griffith T. S., Lynch D. H. (1998) TRAIL: a molecule with multiple receptors and control mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 10, 559–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chaudhary P. M., Eby M., Jasmin A., Bookwalter A., Murray J., Hood L. (1997) Death receptor 5, a new member of the TNFR family, and DR4 induce FADD-dependent apoptosis and activate the NF-κB pathway. Immunity 7, 821–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamaguchi H., Wang H. G. (2004) CHOP is involved in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis by enhancing DR5 expression in human carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45495–45502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gupta S. C., Hevia D., Patchva S., Park B., Koh W., Aggarwal B. B. (2012) Upsides and downsides of reactive oxygen species for cancer: the roles of reactive oxygen species in tumorigenesis, prevention, and therapy. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 16, 1295–1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Torres M., Forman H. J. (2003) Redox signaling and the MAP kinase pathways. Biofactors 17, 287–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guyton K. Z., Xu Q., Holbrook N. J. (1996) Induction of the mammalian stress response gene GADD153 by oxidative stress: role of AP-1 element. Biochem. J. 314, 547–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Newman D. J., Cragg G. M. (2012) Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J. Nat. Prod. 75, 311–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lavie D., Jain M. K. (1967) Tetranortriterpenoids from Melia azadirachia L. Chem. Commun. (Lond.) 278–280 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lavie D., Levy E. C., Jain M. K. (1971) Limonoids of biogenetic interest from Melia azadirachta L. Tetrahedron 27, 3927–3939 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Siddiqui B. S., Tariq Ali S., Kashif Ali S. (2006) A new flavanoid from the flowers of Azadirachta indica. Nat. Prod. Res. 20, 241–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Paul R., Prasad M., Sah N. K. (2011) Anticancer biology of Azadirachta indica L (neem): a mini review. Cancer Biol. Ther. 12, 467–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Siddiqui S. (1942) A note on isolation of three new bitter principles from the neem oil. Curr. Sci. 11, 278–279 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ekong D. E. U. (1967) The structure of nimbolide, a new meliacin from Azadirachta indica. Chem. Commun. 808a [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schwinger M., Ehhammer B., Kraus W. (1984) Proceedings of the 2nd International Neem Conference, Rauischholzhausen, Germany, May 25–28, 1983, p. 181, GTZ GmBH, Eschborn, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chianese G., Yerbanga S. R., Lucantoni L., Habluetzel A., Basilico N., Taramelli D., Fattorusso E., Taglialatela-Scafati O. (2010) Antiplasmodial triterpenoids from the fruits of neem, Azadirachta indica. J. Nat. Prod. 73, 1448–1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nanduri S., Thunuguntla S. S., Nyavanandi V. K., Kasu S., Kumar P. M., Ram P. S., Rajagopal S., Kumar R. A., Deevi D. S., Rajagopalan R., Venkateswarlu A. (2003) Biological investigation and structure-activity relationship studies on azadirone from Azadirachta indica A. Juss. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13, 4111–4115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rodríguez B. (2003) Complete assignments of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 15 limonoids. Magn. Reson. Chem. 41, 206–212 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gupta S. C., Prasad S., Reuter S., Kannappan R., Yadav V. R., Ravindran J., Hema P. S., Chaturvedi M. M., Nair M., Aggarwal B. B. (2010) Modification of cysteine 179 of IκBα kinase by nimbolide leads to down-regulation of NF-κB-regulated cell survival and proliferative proteins and sensitization of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic agents. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 35406–35417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gupta S. C., Reuter S., Phromnoi K., Park B., Hema P. S., Nair M., Aggarwal B. B. (2011) Nimbolide sensitizes human colon cancer cells to TRAIL through reactive oxygen species- and ERK-dependent up-regulation of death receptors, p53, and Bax. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1134–1146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38. Yodkeeree S., Sung B., Limtrakul P., Aggarwal B. B. (2009) Zerumbone enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis through the induction of death receptors in human colon cancer cells: Evidence for an essential role of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 69, 6581–6589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim J. H., Park B., Gupta S. C., Kannappan R., Sung B., Aggarwal B. B. (2012) Zyflamend sensitizes tumor cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through up-regulation of death receptors and down-regulation of survival proteins: role of ROS-dependent CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-homologous protein pathway. Antioxid. Redox. Signal 16, 413–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sung B., Park B., Yadav V. R., Aggarwal B. B. (2010) Celastrol, a triterpene, enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis through the down-regulation of cell survival proteins and up-regulation of death receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11498–11507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41. Sethi G., Ahn K. S., Pandey M. K., Aggarwal B. B. (2007) Celastrol, a novel triterpene, potentiates TNF-induced apoptosis and suppresses invasion of tumor cells by inhibiting NF-κB-regulated gene products and TAK1-mediated NF-κB activation. Blood 109, 2727–2735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chou T. C. (2010) Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 70, 440–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Prasad S., Yadav V. R., Sung B., Reuter S., Kannappan R., Deorukhkar A., Diagaradjane P., Wei C., Baladandayuthapani V., Krishnan S., Guha S., Aggarwal B. B. (2012) Ursolic acid inhibits growth and metastasis of human colorectal cancer in an orthotopic nude mouse model by targeting multiple cell signaling pathways: chemosensitization with capecitabine. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 4942–4953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shenoy K., Wu Y., Pervaiz S. (2009) LY303511 enhances TRAIL sensitivity of SHEP-1 neuroblastoma cells via hydrogen peroxide-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and up-regulation of death receptors. Cancer Res. 69, 1941–1950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Deveraux Q. L., Takahashi R., Salvesen G. S., Reed J. C. (1997) X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature 388, 300–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Taniai M., Grambihler A., Higuchi H., Werneburg N., Bronk S. F., Farrugia D. J., Kaufmann S. H., Gores G. J. (2004) Mcl-1 mediates tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand resistance in human cholangiocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 64, 3517–3524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Suh W. S., Kim Y. S., Schimmer A. D., Kitada S., Minden M., Andreeff M., Suh N., Sporn M., Reed J. C. (2003) Synthetic triterpenoids activate a pathway for apoptosis in AML cells involving downregulation of FLIP and sensitization to TRAIL. Leukemia 17, 2122–2129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kim E. H., Kim S. U., Shin D. Y., Choi K. S. (2004) Roscovitine sensitizes glioma cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis by downregulation of survivin and XIAP. Oncogene 23, 446–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kim Y. H., Jung E. M., Lee T. J., Kim S. H., Choi Y. H., Park J. W., Park J. W., Choi K. S., Kwon T. K. (2008) Rosiglitazone promotes tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis by reactive oxygen species-mediated up-regulation of death receptor 5 and down-regulation of c-FLIP. Free Radic Biol. Med. 44, 1055–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. LeBlanc H., Lawrence D., Varfolomeev E., Totpal K., Morlan J., Schow P., Fong S., Schwall R., Sinicropi D., Ashkenazi A. (2002) Tumor-cell resistance to death receptor–induced apoptosis through mutational inactivation of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 homolog Bax. Nat. Med. 8, 274–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Truneh A., Sharma S., Silverman C., Khandekar S., Reddy M. P., Deen K. C., McLaughlin M. M., Srinivasula S. M., Livi G. P., Marshall L. A., Alnemri E. S., Williams W. V., Doyle M. L. (2000) Temperature-sensitive differential affinity of TRAIL for its receptors: DR5 is the highest affinity receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23319–23325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lu M., Xia L., Hua H., Jing Y. (2008) Acetyl-keto-β-boswellic acid induces apoptosis through a death receptor 5-mediated pathway in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 68, 1180–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wu G. S., Burns T. F., McDonald E. R., 3rd, Jiang W., Meng R., Krantz I. D., Kao G., Gan D. D., Zhou J. Y., Muschel R., Hamilton S. R., Spinner N. B., Markowitz S., Wu G., el-Deiry W. S. (1997) KILLER/DR5 is a DNA damage-inducible p53-regulated death receptor gene. Nat. Genet. 17, 141–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Velculescu V. E., El-Deiry W. S. (1996) Biological and clinical importance of the p53 tumor suppressor gene. Clin. Chem. 42, 858–868 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]