Background: IκB, a cytoplasmic inhibitor of NF-κB, is degraded via the proteasome.

Results: Paradoxically, proteasome inhibitors (PIs) induce IκBα degradation via the lysosome in an IKK-dependent and IKK-independent manner.

Conclusion: PI-induced IκBα degradation results in NF-κB activation that confers resistance to PI-induced cancer cell death.

Significance: This provides a molecular mechanism to enhance the anti-cancer efficacy of PIs.

Keywords: Anticancer Drug, Lung Cancer, Lysosomes, Proteasome, Signal Transduction, GSK-3β, IKK, IκB, Lysosome, Proteasome Inhibitor

Abstract

Proteasome inhibitors (PIs) have been reported to induce apoptosis in many types of tumor. Their apoptotic activities have been suggested to be associated with the up-regulation of molecules implicated in pro-apoptotic cascades such as p53, p21Waf1, and p27Kip1. Moreover, the blocking of NF-κB nuclear translocation via the stabilization of IκB is an important mechanism of PI-induced apoptosis. However, we found that long-term incubation with PIs (PS-341 or MG132) increased NF-κB-regulated gene expression such as COX-2, cIAP2, XIAP, and IL-8 in a dose- and time-dependent manner, which was mediated by phosphorylation of IκBα and its subsequent degradation via the alternative route, lysosome. Overexpression of the IκBα superrepressor (IκBα-SR) blocked PI-induced NF-κB activation. Treatment with lysosomal inhibitors (ammonium chloride or chloroquine) or inhibitors of cathepsins (Z-FF-FMK or Z-FA-FMK) or knock-down of LC3B expression by siRNAs suppressed PI-induced IκBα degradation. Furthermore, we found that both IKK-dependent and IKK-independent pathways were required for PI-induced IκBα degradation. Pretreatment with IKKβ specific inhibitor, SC-514, partially suppressed IκBα degradation and IL-8 production by PIs. Blockade of IKK activity using insolubilization by heat shock (HS) and knock-down by siRNAs for IKKβ only delayed IκBα degradation up to 8 h after treatment with PIs. In addition, PIs induced Akt-dependent inactivation of GSK-3β. Inactive GSK-3β accelerated PI-induced IκBα degradation. Overexpression of active GSK-3β (S9A) or knock-down of GSK-3β delayed PI-induced IκBα degradation. Collectively, our data demonstrate that long-term incubation with PIs activates NF-κB, which is mediated by IκBα degradation via the lysosome in an IKK-dependent and IKK-independent manner.

Introduction

The 26S proteasome, a multicatalytic enzyme complex that is expressed in the nucleus and cytoplasm of all eukaryotic cells, has emerged as a novel putative target for cancer therapy. It is the main intracellular, nonlysosomal, ATP-dependent proteolytic system by which various proteins involved in signal transduction, cell-cycle regulation, and apoptosis are degraded (1–3). Inhibition of this ubiquitin-mediated degradation of several regulatory proteins has been reported to induce cellular apoptosis in several types of cancer including lung cancer (4), colon cancer (5), breast cancer (6), and pancreatic cancer (7) as well as multiple myeloma (8). Proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib (N-pyrazinecarbonyl-l-phenylalanine-l-leucine boronic acid; known as PS-341)2 and synthetic peptide aldehydes MG132 show anti-tumor activity. Their molecular mechanisms of anti-tumor activity include the rapid accumulation of p53 and p27kip1, phosphorylation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and c-Jun, stabilization of BH3 pro-apoptotic proteins BIK, NOXA, and BIM, down-regulation of anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL and stabilization of cyclin D, E, and A (9–11). Moreover, proteasome inhibitors inhibit NF-κB activity by blocking the degradation of its cytoplasmic inhibitor, IκB (12).

NF-κB, a pleiotropic transcription factor, is normally sequestered in the cytoplasm in an inactive form, bound to the inhibitory proteins (IκBs). NF-κB promotes the expression of various cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and TNF-α and adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 as well as anti-apoptotic proteins such as survivin, IAP1/2, Bfl-1/A1, and cFLIP. Upon cell stimulation by a broad variety of stimuli including viral infection, growth factors, cytokines, or chemotherapeutic agents, IKKα/β is activated. Active IKK directly phosphorylates IκBα at Ser32 and Ser36 residues, leading to ubiquitination at Lys21 and Lys22, and degradation of IκBα through the 26S proteasome, resulting in nuclear translocation of the NF-κB subunit complexes (13–15). In the nucleus, NF-κB binds to its cognate site, κB element, and transactivates the downstream genes (13–15). Many types of cancer show constitutive or increased activity of NF-κB and increased activation of NF-κB confers resistance to cell death (16). Therefore, NF-κB has been suggested to be related to increased survival in many tumor cells.

However, in this study, we found that long-term incubation with proteasome inhibitors (PS-341 or MG132) induces irreversible degradation of IκBα via an alternative pathway, lysosome. After treatment with PIs, the IKK-dependent mechanism during early phase and IKK-independent mechanism during late phase are responsible for PI-induced IκBα degradation, and inactive GSK-3β is involved in phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα by PIs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

A549 cells, representing type II alveolar epithelial cells, and NCI-H157, derived from squamous cell lung cancer, were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% CO2.

Reagents

Anti-IκBα, anti-IKKα, anti-IKKβ, anti-cIAP2, anti-actin, anti-COX-2, anti-Akt, anti-GSK-3, anti p-Tau, and anti-HA antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-p-IκBα, anti-XIAP, anti-ubiquitin, anti-p-Akt, anti-p-GSK-3β, anti-GSK-3β, and anti-LC3B antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Goat anti-rabbit/mouse/goat secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The proteasome inhibitor N-carbobenzoxyl-Leu-Leu-Leu-leucinal (MG132) was obtained from the Peptide Institute (Osaka, Japan), and PS-341 was kindly donated by Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, MA). Recombinant Tau protein was obtained from Panvera (Madison, WI). Recombinant human TNF-α was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), prepared as a stock solution in distilled water, and stored at −70 °C until needed. Chloroquine, ammonium chloride, lithium chloride, and protein G-Sepharose beads were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Z-FA-FMK (an inhibitor of cathepsins) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Z-FF-FMK (cathepsin B & L inhibitor) was from BioVision (Milpitas, CA). Lipofectamine 2000 was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). IKK-β inhibitor, SC-514 was from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany).

Quantitative Real-time PCR

Total RNA from NCI-H157 cells was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the Reverse Transcription system (Promega, Madison, WI). PCR amplification was performed with 2× TaqMan gene expression master mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). The primer information is as follows: cIAP2 (Hs00985031_g1), IL-8 (Hs00174103_m1), GAPDH (Hs99999905 _m1). The primers were obtained from Applied Biosystems.

Power SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems) was used for PCR amplification for COX-2. COX-2 primers (foward, 5′-TGAGCATCTACGGTTTGC TG-3′; and reverse, 5′-TGCTTGTCTGGAACAACTGC-3′) were used.

Western Blot Analysis

Proteins were resolved by 4–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk-PBS-0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h before being incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies in 5% skim milk-PBS-0.1% Tween 20. The membranes were then washed three times in 1× PBS-0.1% Tween 20 and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies in 5% skim milk-PBS-0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h. After successive washes, the membranes were developed using an ECL kit.

Determination of Cytokine Secretion

Cytokine levels in culture supernatants were determined using a commercially available ELISA kit for IL-8, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

20S Proteasome Activity Assay

Proteasome activity was determined using a 20S proteasome activity assay kit (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) according to the manufacturer's specifications. In brief, cell lysates were incubated with proteasome substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC for 1 h at 37 °C. The fluorescence from the mixture was quantified using a 380/460 nm filter set in a fluorometer.

Kinase Assay

The activities of IKK or GSK-3β were assessed by an in vitro kinase assay. In brief, the IKK or GSK-3β complex was immunoprecipitated with anti-IKKα or anti-GSK-3β antibodies. The immunoprecipitates were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min in a kinase buffer containing 0.5 μg of recombinant IκBα (or 0.1 μg/μl recombinant Tau) and 0.2 mm of ATP. The kinase reaction products were subjected to SDS-PAGE in 4–12% gels and then was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-p-IκBα or anti-p-Tau antibodies.

Transfection of siRNAs

Transfection of siRNAs targeting LC3B, IKKβ, or GSK-3β genes (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's specifications. 100 nm siRNA was sufficient to mediate silencing. After 48 h, the cells were used in the experiments indicated.

Transduction of Adenoviruses or Transfection of Plasmid Vectors

Cells were plated in a 6-well tissue culture plate. After overnight incubation, cells were transduced at multiplicities of infection (MOI) of 50 by adenovirus vector expressing IκBα superrepressor (IκBα-SR) cDNA in which serine 32/36 was substituted with alanine in complete RPMI for 2 h with gentle shaking, and then washed with PBS and incubated with growth medium at 37 °C, 5% CO2 until use. Cells were transfected with plasmid vectors expressing HA-tagged WT-Akt, dominant negative Akt (DN-Akt), WT-GSK-3β, or GSK-3β cDNA in which serine 9 was substituted with non-phosphorylatable alanine (S9A). After 48 h, the cells were used in the experiments indicated.

Heat Treatment

Heat stress (HS) was induced by incubating cells in a water bath at 43 °C. After HS treatment, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium. Cells were allowed to recover in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C.

Statistical Analysis

Data were subjected to Student's t test for analysis of statistical significance, and a p value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

PIs Increased NF-κB-regulated Gene Expression

To determine the impact of proteasome inhibition on the NF-κB pathway, we first analyzed the dose- and time-dependent expression of NF-κB-regulated genes by PS-341 or MG132. Upon PI stimulation, transcripts of COX-2, cIAP2, and IL-8 were induced (Fig. 1A). COX-2 was hardly detectable in the basal state. More than 10 nm of PS-341 or 1 μm of MG132 was required to increase COX-2 protein expression. COX-2 started to increase at 4 h after treatment with PS-341 or MG132 and increased further in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1, B and C). The time course of PI-induced cIAP2 expression was similar to that of COX-2 expression (Fig. 1D). Moreover, Fig. 1, E and F show a significant increase in XIAP expression and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-8 in PS-341-treated cells. These results indicate that PIs up-regulate the expression of NF-κB-regulated genes.

FIGURE 1.

PIs increased NF-κB-regulated protein expression. A, NCI-H157 cells were treated with PS-341 (50 nm) and MG132 (20 μm) for the indicated times. Total RNA from the cells was isolated, and quantitative real-time PCR for COX-2, cIAP2, IL-8, and GAPDH was performed. B, NCI-H157 (H157) or A549 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of PS-341 or MG132 for 8 h. C and D, cells were incubated with PS-341 (50 nm) or MG132 (20 μm) for the indicated times. E, NCI-H157 cells were treated with PS-341 (2–100 nm) for 8 h. Total cellular extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis for COX-2, cIAP2, XIAP, and actin. F, NCI-H157 cells were treated with PS-341 (10–100 nm) or TNF-α (10 ng/ml) as a positive control for 24 h. IL-8 concentrations in media were determined by ELISA. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of triplicates. **, p < 0.05 versus control cells. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

PI-induced Up-regulation of NF-κB-regulated Proteins Was Associated with IκBα Phosphorylation and Its Subsequent Degradation

As NF-κB exists in an inactive form in the cytoplasm bound to inhibitory protein IκBα, degradation of IκBα through the 26S proteasomal pathway is a prerequisite for the activation of NF-κB. To test the possibility that IκBα degradation is required for PI-induced up-regulation of NF-κB-regulated proteins, we measured IκBα protein levels from control and PI-treated cells by Western blot analysis. IκBα was markedly degraded after 4 h of incubation with PS-341 or MG132, and did not recover up to 24 h (Fig. 2, A and B). Because IκBα degradation is preceded by phosphorylation of two serine residues (Ser32 and Ser36), we tested the levels of phosphorylated IκBα from PI-treated cells. As expected, IκBα phosphorylation occurred earlier than IκBα degradation. Phosphorylation of IκBα was increased 4 h after PS-341 or MG132 treatment and returned to basal levels at 8 h (Fig. 2B). We next evaluated whether IκBα phosphorylation is necessary for the PI-induced degradation of IκBα and COX-2 induction. Cells were infected with either control adenovirus or adenovirus expressing IκBα-superrepressor (Ad-IκBα-SR) at the dose of 50 MOI for 48 h, and then stimulated with PS-341 (50 nm) for 24 h in NCI-H157 and A549 cells. IκBα superrepressor (IκBα-SR) in which serine 32/36 was substituted with alanine is not phosphorylated, and it was not degraded by PS-341. This result indicates that IκBα phosphorylation is necessary for its degradation by PS-341 (Fig. 2C). PS-341-induced up-regulation of COX-2 was completely suppressed in Ad-IκBα-SR-infected cells, which implies that IκBα degradation is necessary for COX-2 induction by PS-341 (Fig. 2C). Overexpression of IκBα-SR has been well-known to block NF-κB activation (17). However, the possibility that strong overexpression interferes with the translation of COX-2 cannot be excluded. Taken together, these observations indicate that PI-induced up-regulation of NF-κB-regulated proteins is associated with IκBα phosphorylation and its subsequent degradation.

FIGURE 2.

PI-induced up-regulation of NF-κB-regulated proteins was associated with IκBα phosphorylation and its subsequent degradation. A, NCI-H157 or A549 cells were treated with PS-341 (2–100 nm) or MG132 (1–50 μm) for 8 h. B, cells were incubated with PS-341 (50 nm) or MG132 (20 μm) for the indicated times. C, cells were infected with either IκBα-SR adenovirus vector or control adenovirus. Forty-eight hours after transduction, cells were treated with PS-341 (50 nm) for 24 h. Total cellular extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis for IκBα, p-IκBα, COX-2, and actin. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

PI-mediated Degradation of IκBα Is through the Lysosomal Pathway

Proteasome inhibitors have been shown to block proteolysis of the phosphorylated IκBα through the 26S proteasome in response to IL-1β and TNF-α (18). Paradoxically, long-term incubation with PIs induced IκBα degradation in this study. To confirm whether proteasome activity was effectively blocked by PI, a time-dependent proteasome activity was measured after treatment with PS-341. Proteasome activity was effectively suppressed by PS-341 for up to 24 h (Fig. 3A). As proteolysis of ubiquitinated proteins via the proteasomal pathway was blocked, ubiquitinated proteins in whole cell lysates were significantly increased in PS-341-treated cells (Fig. 3B). Moreover, short-term incubation (1 h) of MG132 blocked TNF-α-induced IκBα degradation (Fig. 3C), which supports that PIs effectively block proteasome activity.

FIGURE 3.

PI-mediated degradation of IκBα is through the lysosomal pathway. NCI-H157 cells were treated with PS-341 (50 nm) for the indicated times (A) or 24 h (B). The 20S proteasome activity assay was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” **, p < 0.05 versus control cells. C, NCI-H157 cells were pretreated with MG132 (20 μm) for 1 h and stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 30 min. D–F, cells were pretreated with ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, 5–50 mm) or chloroquine (100–200 μm) for 2 h followed by PS-341 (50 nm) for 8 h or TNF-α for 30 min. G, NCI-H157 cells were pretreated with two different inhibitors of cathepsins (Z-FF-FMK, 40 μm or Z-FA-FMK, 10–100 μm) for 1 h, and the cells were stimulated with PS-341 (50 nm) for the indicated times. H, NCI-H157 cells were transfected with LC3B or control siRNAs. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were treated with PS-341 or MG132 for the indicated times. Total cellular extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis for ubiquitin (Ub), IκBα, LC3B, and actin. Results are representative of three separate experiments. P, positive control; L, Lactasystin.

Eukaryotic cells have two major systems for protein degradation: the proteasome by which the majority of proteins (more than 80%) are degraded and the lysosomal apparatus. To test whether the lysosomal pathway is involved in this process, cells were pretreated with lysosomal inhibitors, chloroquine (100 and 200 μm) and ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, 5–50 mm) for 2 h before addition of PS-341 and TNF-α. Pretreatment with chloroquine or NH4Cl stabilized IκBα in response to PS-341 (Fig. 3, D and E). In contrast, both lysosomal inhibitors had no effect on TNF-α-induced degradation of IκBα (Fig. 3F). Moreover, treatment with inhibitors of lysosomal digestive enzymes such as cathepsins (Z-FF-FMK or Z-FA-FMK) suppressed PI-induced IκBα degradation (Fig. 3G).

Autophagy is one of the intracellular protein degradation mechanisms through the lysosomal machinery. During autophagy, light chain 3B (LC3B)-II expression is elevated. LC3B-II accumulation is a hallmark of autophagy activation (19). Both PS-341 and MG132 induced time-dependent LC3B accumulation and knock-down of LC3B using siRNAs suppressed IκBα degradation in PS-341- or MG132-treated NCI-H157 cells (Fig. 3H). These results indicate that PI-induced IκBα degradation requires the activity of lysosomal hydrolases.

IKK Activity Is Required for the Rapid PI-induced IκBα Degradation

IκBα degradation through the proteasomal pathway requires IκBα phosphorylation by IKK. However, its role in PI-induced IκBα degradation through the lysosomal pathway is not clear. Thus, we next evaluated whether IKK activation is required in PI-induced IκBα degradation through the lysosomal pathway. To evaluate the effect of PI treatment on IKK activity, IKK activities were measured by immune complex kinase assays after PS-341 or MG132 stimulation. PS-341 and MG132 activated IKK (Fig. 4, A and B) up to 8 h. When IKK activity was suppressed by SC-514 (IKKβ specific inhibitor) pretreatment, PS-341-induced IκBα degradation and IL-8 production were partially blocked (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, phosphorylation of IκBα was delayed (Fig. 4C), which suggests that IKK-independent mechanism(s) might be associated with PI-induced phosphorylation of IκBα. To further confirm if IKK activity is necessary for PI-induced IκBα degradation, IKK activity was blocked by two different approaches: by insolubilizing IKK and by knockdown of IKKβ using siRNAs. Neither IKKα nor IKKβ expression was detected in soluble extracts up to 10 h of recovery after heat shock (HS) at 43 °C for 1 h as previously reported (20). PS-341-induced IκBα phosphorylation and degradation were delayed in HS-treated cells (Fig. 5A), by which PS-341- or TNF-α-induced IKK activity was completely blocked (Fig. 5, B and C). In accordance with this, knockdown of IKKβ in cells transfected with IKKβ siRNAs delayed PS-341-induced IκBα phosphorylation and its subsequent degradation (Fig. 5, D and E). In contrast, TNF-α-induced IκBα degradation, which is known to be dependent on IKK activation, was suppressed by HS treatment or by knockdown of IKKβ (Fig. 5, C and F). Taken together, these results imply that IKK activity is required for PI-induced IκBα degradation during early phase, and an IKK-independent mechanism might regulate PI-induced IκBα phosphorylation and degradation during late phase.

FIGURE 4.

IKK activity is required for the rapid PI-induced IκBα degradation (1). A and B, NCI-H157 cells were treated with PS-341 or MG132 for the indicated times and with TNF-α for 5 min. The IKK complex was immunoprecipitated using an anti-IKKα antibody, and IKK assays were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” C, cells were pretreated with IKK-β inhibitor, SC-514 (100 μm) for 1 h followed by PS-341 (50 nm) for the indicated times (upper panel). Pretreated cells with SC-514 were incubated with PS-341 or TNF-α for 24 h (lower panel). Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis for IκBα, p-IκBα, and actin. The concentrations of IL-8 in supernatant fluid were quantitated by ELISA. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of triplicates. *, p < 0.05 versus TNF-α- or PS-341-treated cells. Results are representative of three separate experiments. K.A., kinase assay.

FIGURE 5.

IKK activity is required for the rapid PI-induced IκBα degradation (2). A–C, NCI-H157 cells were exposed to HS at 43 °C for 1 h and then stimulated with PS-341 (50 nm) for the indicated times or TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 5 min. D–F, cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting IKKβ gene and control siRNAs. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with PS-341 (50 nm) for the indicated times and TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 30 min. IKK assays were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against IκBα, p-IκBα, IKKα, IKKβ, and actin. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

Inactivation of GSK-3β via the PI3K/Akt Pathway Is Related to the Acceleration of PI-induced IκBα Degradation

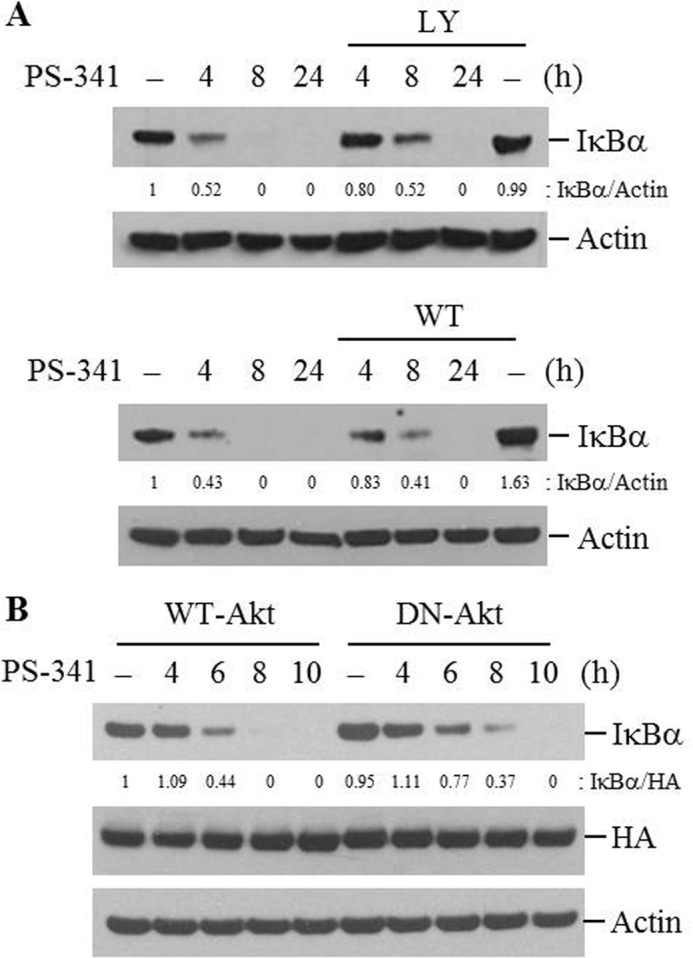

The role of the PI3K/Akt pathway was evaluated in PI-induced IκBα degradation. Active phosphorylated Akt was up-regulated after incubation with PIs for 4 h, and returned to baseline at 8 h or 24 h (Fig. 6, A and B). When PI-induced activation of Akt was blocked by treatment with PI3K/Akt pathway inhibitors (LY294002 or wortmanin) or overexpression of dominant-negative Akt (DN-Akt) plasmid vector, IκBα degradation by PIs was delayed (Fig. 7, A and B).

FIGURE 6.

PIs inactivate GSK-3β via the PI3K/Akt pathway. A and B, NCI-H157 were treated with PS-341(50 nm) or MG132 (20 μm) for the indicated times. Total cellular extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis for p-Akt, Akt, p-GSK-3β, and GSK-3. C, NCI-H157 cell were treated with PS-341 (10–50 nm) for 24 h. GSK-3β was immunoprecipitated with an anti-GSK-3β antibody, and GSK-3β activity assays were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” D, NCI-H157 cells were pretreated with wortmanin (WT, 50 nm) for 2 h followed by PS-341 (50 nm) for the indicated times. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis for p-GSK-3β and actin. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

FIGURE 7.

Akt activation is associated with the acceleration of PI-induced IκBα degradation. A, NCI-H157 cells were pretreated with LY294002 (LY, 50 μm) or wortmanin (WT, 50 nm) for 2 h followed by PS-341 (50 nm) for the indicated times. B, cells were transfected with WT-Akt or DN-Akt plasmid vectors. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with PS-341 for the indicated times. Total cellular extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis for IκBα, HA, and actin. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

Because GSK-3β is one of the well-known downstream molecules of Akt, we investigated whether PS-341-induced IκBα degradation is mediated through GSK-3β. The inactive phosphorylated GSK-3β at serine 9 (p-GSK-3β) was increased by PIs time-dependently (Fig. 6, A and B). GSK-3β is known to be constitutively active and is inactivated by phosphorylation at serine 9. To confirm that increased p-GSK-3β is associated with decreased activity, GSK-3β activity was measured using an in vitro immune complex kinase assay after treating cells with PS-341. GSK-3β was constitutively active, and its activity was reduced by PS-341 treatment (Fig. 6C). When Akt activation was blocked with wortmanin, GSK-3β inactivation by PS-341 was markedly suppressed (Fig. 6D). These findings suggest that PS-341 inactivates GSK-3β, and it was mediated by activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway.

To further evaluate the role of GSK-3β inactivation on IκBα degradation by PIs, we assessed the impact of blocking GSK-3β inactivation on PS-341-induced IκBα degradation. Cells were transfected with plasmid vector expressing HA-tagged GSK-3β cDNA, in which serine 9 was substituted for non-phosphorylatable alanine, GSK-3β (S9A) or WT-GSK-3β vector. Because GSK-3β (S9A) cannot be inactivated, it functions as a constitutively active GSK-3β. The overexpression of GKS-3β (S9A) was confirmed by immunoblotting against HA (Fig. 8A). PS-341-induced IκBα degradation was delayed in GSK-3β (S9A) overexpressing cells compared with those in WT-GSK-3β-overexpressed cells (Fig. 8A). We next evaluated the effect of GSK-3β knockdown on PS-341-induced IκBα degradation. GSK-3β expression was decreased after 48 h and further decreased with prolonged incubation up to 72 h after siRNAs treatment (Fig. 8B). GSK-3β siRNAs did not affect PS-341-induced Akt activation (data not shown). When GSK-3β expression was down-regulated by siRNAs, PS-341-induced IκBα degradation was delayed (Fig. 8C). Moreover, GSK-3β inactivation was induced by treatment with lithium chloride (LiCl), a selective inhibitor of GSK-3β. LiCl induced IκBα degradation in both lung cell lines, and the increase in phosphorylated p65 and COX-2 proteins (data not shown). Taken together, these findings indicate that the GSK-3β inactivation via the PI3K/Akt pathway accelerates PI-induced IκBα degradation.

FIGURE 8.

Inactivation of GSK-3β is associated with the acceleration of PI-induced IκBα degradation. A, NCI-H157 cells were transfected with WT-GSK-3β or GSK-3β (S9A) plasmid vectors. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with PS-341 for the indicated times. B and C, cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting the GSK-3β gene. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with PS-341 for the indicated times. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis for IκBα, HA, GSK-3, Akt, p-IκBα, and actin. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

NF-κB activation is associated with the resistance of lung cancer cells to TNF-α-induced apoptosis. Proteasome inhibition prevents NF-κB activation and enhances TNF-α-induced cell death (16). Moreover, inducible activation of NF-κB suppresses the apoptotic response to irradiation and chemotherapy. Treatment with PS-341 blocks activation of NF-κB induced by chemotherapy agents such as SN-38, the active metabolite of the topoisomerase I inhibitor, in human colorectal cancer cells (5) or gemcitabine, a nucleoside analog, in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells (22). However, in this study, treatment with PS-341 or MG132 induced rather than inhibited NF-κB activity and increased the expression of NF-κB-regulated genes COX-2, cIAP2, IL-8, and XIAP. This result is consistent with other observations indicating that different proteasome inhibitors (epoxomicin or ALLN) induce NF-κB nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity on endometrial carcinoma cell lines (23) and colon cancer cells (24). PS-341 treatment increased ubiquitinated proteins in whole cell lysate. The activity of the proteasome started to decrease 30 min after stimulation with PS-341 and was sustained up to 24 h. IκBα is one of the selected proteins affected by inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Proteasome inhibition elevates IκBα levels and leads to inhibition of NF-κB activity. However, we showed that PS-341-induced activation of NF-κB was mediated by IκBα phosphorylation and subsequent degradation. This suggests that other proteolytic systems, apart from the 26S proteasome, might be involved in PI-induced IκBα degradation.

There are several circumstances in which participation of other protein degradation systems have been described. The calcium-activated calpain system (25–26), caspases (27), lysosomes (28), and unknown proteinases have been suggested to be responsible for IκB degradation. In this study, lysosomal inhibitor (chloroquine or NH4Cl) and cathepsin inhibitors (Z-FF-FMK or Z-FA-FMK) suppressed PI-induced IκBα degradation, but did not affect TNF-α-mediated IκBα degradation in NCI-H157 cells and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or CpG-oligodeooxynucleotide (CpG-ODN)-induced IκBα degradation in macrophage cell line (data not shown). TNF-α-induced IκBα degradation in NCI-H157 cells or LPS (or CpG-ODN)-induced IκBα degradation in macrophages were blocked by short-term incubation (1 h) with PIs (data not shown), which supports that PIs effectively block proteasome activity, and prolonged incubation with PIs degrades IκBα through the non-proteasomal pathway. Blocking of autophagy activation by knockdown of LC3B expression suppressed PI-induced IκBα degradation, which confirm that PIs induce IκBα degradation via the autophagy-lysosomal pathway. A previous report shows that a portion of intracellular IκBα is located in the lysosome as well as in the cytosol and microsomes and that the transport of IκB into lysosome is selective (28). In the report, ubiquitination and phosphorylation of IκBα is not required for its targeting to lysosome under conditions of nutrient deprivation. In our study, overexpression of IκB-SR suppressed PI-induced IκBα degradation and subsequently inhibited NF-κB activation, which suggests that phosphorylation of IκBα is necessary for PI-induced IκBα degradation. However, to evaluate if translocation to the lysosome needs ubiquitination of IκBα in PI-treated cells, further detailed study is required. Moreover, a recent report suggests that PS-341 induces caspase-independent, leupeptin-sensitive protease-independent, but calpain-dependent IκBα proteolysis (29). IκB degradation liberates NF-κB for nuclear translocation, where it drives transcription of the downstream genes, including cIAP, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, COX-2, XIAP, and others (30). NF-κB activates cIAP1 and cIAP2 to inhibit TNF-α-induced apoptosis by blocking caspase-8 activity. COX-2 has been known to promote angiogenesis and is found up-regulated in some cancer cells. In agreement with this, we showed that IκBα-SR gene transfer blocked PS-341-induced increase in COX-2 expression. Pretreatment with DHMEQ, which inhibits DNA binding affinity of NF-κB and knockdown of p65 using siRNAs, suppressed COX-2 induction by PS-341 (data not shown). These results suggest that PIs activate the NF-κB cascade via lysosomal degradation of IκBα, resulting in induction of anti-apoptotic genes, such as cIAP2 and COX-2 in lung cancer cells.

The first step of IκBα degradation involves phosphorylation of IκBα by the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. The IKK complex is composed of several kinases including IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ, and it requires phosphorylation by NIK to become activated. Our previous study showed that heat stress (HS) insolubilizes IKKs, resulting in the loss of IKK activity (20). As expected, PS-341- or TNF-α-induced IKK activity was completely suppressed by HS, and IKKα/β levels were reduced in soluble extracts after HS. However, phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα by PIs were delayed by HS as well as by knock-down of IKKβ. These findings suggest the possibility of other IKK-independent pathway(s) involvement regarding PI-induced degradation of IκBα. Similarly, a previous study showed that IκBα degradation in response to anti-cancer reagents such as doxorubicin was mediated by an IKK-independent mechanism (31).

To determine the responsible factor(s), we evaluated the involvement of signaling mediators activated by PIs. Our data show that simultaneous activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway was involved in PS-341-induced IκBα degradation. Treatment with PI3K/Akt inhibitor, LY294002 or wortmannin, and overexpression of dominant negative Akt (DN-Akt) delayed IκBα degradation by PIs. Moreover, inactivation of GSK-3β, one of the well-known downstream effectors of Akt, mediated the rapid degradation of IκBα by PIs. Akt-mediated inactivation of GSK-3β has been involved in many other signaling pathways including the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (32). In addition, the inhibitory effect of active GSK-3β on NF-κB-dependent transcription has been reported to be related to prevention of IKK activity, which occurs as a result of competitive binding of GSK-3β to NF-κB essential modifier (NEMO) (33). Inactivation of GSK-3β, however, has been suggested to prevent TNF-α-induced IκBα degradation, but had no effect on the IKKβ activation (34). In our study, blockade of GSK-3β inactivation by overexpression of constitutively active GSK-3β (S9A) and knock-down of GSK-3β, delayed PI-induced IκBα degradation, which implies that inactive GSK-3β plays a positive role on PI-induced IκBα degradation. IKK activity, phosphorylation of p65, or NF-κB DNA binding activity are putative target steps of GSK-3β action on the NF-κB pathway (21, 35, 36). In our study, PI-induced IκBα phosphorylation was reduced in cells with decreased levels of GSK-3β. However, IKK activity was not affected by knock-down of GSK-3β (data not shown).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to find that PIs activate NF-κB, which is mediated by IκBα degradation via the autophagy-lysosomal pathway. The IKK-dependent mechanism in the earlier stage and IKK-independent mechanism in the late stage are required for PI-induced IκBα degradation. Moreover, inactive GSK-3β as well as active IKK mediates PI-induced IκBα degradation in lung cancer cells. Thus, prevention of IκBα degradation by targeting its upstream regulators or the responsible proteolysis pathway will augment anti-tumor activity of PIs.

Acknowledgment

We thank Jinwoo Lee for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Grant 0320030170 from the Seoul National University Hospital.

- PS-341

- bortezomib

- PI

- proteasome inhibitor

- IKK

- IκB kinase

- HS

- heat shock

- GSK-3β

- glycogen synthase kinase-3β.

REFERENCES

- 1. Goldberg A. L., Stein R., Adams J. (1995) New insights into proteasome function: from archaebacteria to drug development. Chem. Biol. 2, 503–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coux O., Tanaka K., Goldberg A. L. (1996) Structure and functions of the 20S and 26S proteasomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65, 801–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Richardson P. G., Mitsiades C., Hideshima T., Anderson K. C. (2005) Proteasome inhibition in the treatment of cancer. Cell Cycle 4, 290–296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ling Y. H., Liebes L., Jiang J. D., Holland J. F., Elliott P. J., Adams J., Muggia F. M., Perez-Soler R. (2003) Mechanisms of proteasome inhibitor PS-341-induced G(2)-M-phase arrest and apoptosis in human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 1145–1154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cusack J. C., Jr., Liu R., Houston M., Abendroth K., Elliott P. J., Adams J., Baldwin A. S., Jr. (2001) Enhanced chemosensitivity to CPT-11 with proteasome inhibitor PS-341: implications for systemic nuclear factor-κB inhibition. Cancer Res. 61, 3535–3540 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Teicher B. A., Ara G., Herbst R., Palombella V. J., Adams J. (1999) The proteasome inhibitor PS-341 in cancer therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 5, 2638–2645 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nawrocki S. T., Carew J. S., Pino M. S., Highshaw R. A., Dunner K., Jr., Huang P., Abbruzzese J. L., McConkey D. J. (2005) Bortezomib sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Res. 65, 11658–11666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hideshima T., Richardson P., Chauhan D., Palombella V. J., Elliott P. J., Adams J., Anderson K. C. (2001) The proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits growth, induces apoptosis, and overcomes drug resistance in human multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 61, 3071–3076 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rajkumar S. V., Richardson P. G., Hideshima T., Anderson K. C. (2005) Proteasome inhibition as a novel therapeutic target in human cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 630–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fennell D. A., Chacko A., Mutti L. (2008) BCL-2 family regulation by the 20S proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Oncogene 27, 1189–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davies A. M., Lara P. N., Jr., Mack P. C., Gandara D. R. (2007) Incorporating bortezomib into the treatment of lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, s4647–4651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sunwoo J. B., Chen Z., Dong G., Yeh N., Crowl Bancroft C., Sausville E., Adams J., Elliott P., Van Waes C. (2001) Novel proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits activation of nuclear factor-κB, cell survival, tumor growth, and angiogenesis in squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 7, 1419–1428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baldwin A. S., Jr. (1996) The NF-κB and IκB proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 14, 649–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barnes P. J., Karin M. (1997) Nuclear factor-κB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 1066–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ghosh S., May M. J., Kopp E. B. (1998) NF-κB and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16, 225–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim J. Y., Lee S., Hwangbo B., Lee C. T., Kim Y. W., Han S. K., Shim Y. S., Yoo C. G. (2000) NF-κB activation is related to the resistance of lung cancer cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 273, 140–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park G. Y., Le S., Park K. H., Le C. T., Kim Y. W., Han S. K., Shim Y. S., Yoo C. G. (2001) Anti-inflammatory effect of adenovirus-mediated IκBα overexpression in respiratory epithelial cells. Eur. Respir. J. 18, 801–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yoo C. G., Lee S., Lee C. T., Kim Y. W., Han S. K., Shim Y. S. (2000) Anti-inflammatory effect of heat shock protein induction is related to stabilization of IκBα through preventing IκB kinase activation in respiratory epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 164, 5416–5423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Klionsky D. J., Abeliovich H., Agostinis P., Agrawal D. K., Aliev G., et al. (2008) Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy 4, 151–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee K. H., Hwang Y. H., Lee C. T., Kim Y. W., Han S. K., Shim Y. S., Yoo C. G. (2004) The heat-shock-induced suppression of the IκB/NF-κB cascade is due to inactivation of upstream regulators of IκBα through insolubilization. Exp. Cell Res. 299, 49–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Steinbrecher K. A., Wilson W., 3rd., Cogswell P. C., Baldwin A. S. (2005) Glycogen synthase kinase 3β functions to specify gene-specific, NF-κB-dependent transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 8444–8455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Denlinger C. E., Rundall B. K., Keller M. D., Jones D. R. (2004) Proteasome inhibition sensitizes non-small-cell lung cancer to gemcitabine-induced apoptosis. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 78, 1207–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dolcet X., Llobet D., Encinas M., Pallares J., Cabero A., Schoenenberger J. A., Comella J. X., Matias-Guiu X. (2006) Proteasome inhibitors induce death but activate NF-κB on endometrial carcinoma cell lines and primary culture explants. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22118–22130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Németh Z. H., Wong H. R., Odoms K., Deitch E. A., Szabó C., Vizi E. S., Haskó G. (2004) Proteasome inhibitors induce inhibitory κB (IκB) kinase activation, IκBα degradation, and nuclear factor κB activation in HT-29 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 65, 342–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen F., Lu Y., Kuhn D. C., Maki M., Shi X., Sun S. C., Demers L. M. (1997) Calpain contributes to silica-induced IκB-α degradation and nuclear factor-κB activation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 342, 383–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miyamoto S., Seufzer B. J., Shumway S. D. (1998) Novel IκBα proteolytic pathway in WEHI231 immature B cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 19–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. White D. W., Gilmore T. D. (1996) Bcl-2 and CrmA have different effects on transformation, apoptosis and the stability of IκB-α in chicken spleen cells transformed by temperature-sensitive v-Rel oncoproteins. Oncogene 13, 891–899 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cuervo A. M., Hu W., Lim B., Dice J. F. (1998) IκB is a substrate for a selective pathway of lysosomal proteolysis. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 1995–2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li C., Chen S., Yue P., Deng X., Lonial S., Khuri F. R., Sun S. Y. (2010) Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 (bortezomib) induces calpain-dependent IκB(α) degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 16096–16104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Orlowski R. Z., Baldwin A. S., Jr. (2002) NF-κB as a therapeutic target in cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 8, 385–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tergaonkar V., Bottero V., Ikawa M., Li Q., Verma I. M. (2003) IκB kinase-independent IκBα degradation pathway: functional NF-κB activity and implications for cancer therapy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 8070–8083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Doble B. W., Woodgett J. R. (2003) GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J. Cell Sci. 116, 1175–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sanchez J. F., Sniderhan L. F., Williamson A. L., Fan S., Chakraborty-Sett S., Maggirwar S. B. (2003) Glycogen synthase kinase 3β-mediated apoptosis of primary cortical astrocytes involves inhibition of nuclear factor κB signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 4649–4662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eto M., Kouroedov A., Cosentino F., Lüscher T. F. (2005) Glycogen synthase kinase-3 mediates endothelial cell activation by tumor necrosis factor-α. Circulation 112, 1316–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Takada Y., Fang X., Jamaluddin M. S., Boyd D. D., Aggarwal B. B. (2004) Genetic deletion of glycogen synthase kinase-3β abrogates activation of IκBα kinase, JNK, Akt, and p44/p42 MAPK but potentiates apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 39541–39554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schwabe R. F., Brenner D. A. (2002) Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation and apoptosis in hepatocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 283, G204–G211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]