Abstract

Formation of appropriate synaptic connections is critical for proper functioning of the brain. After initial synaptic differentiation, active synapses are stabilized by neural activity-dependent signals to establish functional synaptic connections. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying activity-dependent synapse maturation remain to be elucidated. Here we show that activity-dependent ectodomain shedding of SIRPα mediates presynaptic maturation. Two target-derived molecules, FGF22 and SIRPα, sequentially organize the glutamatergic presynaptic terminals during the initial synaptic differentiation and synapse maturation stages, respectively, in the mouse hippocampus. SIRPα drives presynaptic maturation in an activity-dependent fashion. Remarkably, neural activity cleaves the extracellular domain of SIRPα, and the shed ectodomain, in turn, promotes the maturation of the presynaptic terminal. This process involves CaM kinase, matrix metalloproteinases, and the presynaptic receptor CD47. Finally, SIRPα-dependent synapse maturation has significant impacts on synaptic function and plasticity. Thus, ectodomain shedding of SIRPα is an activity-dependent trans-synaptic mechanism for the maturation of functional synapses.

INTRODUCTION

Synapses are the sites of information processing between neurons in the brain. Defects in synaptic circuitry in the hippocampus, a structure critical for long-term memory formation, emotional processing and social behavior, are associated with a variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders including Fragile X syndrome, autism, epilepsy, and schizophrenia1–3. Thus, proper assembly of hippocampal synapses is essential for optimal functioning of the brain. To organize synapse formation, signals are exchanged between pre- and postsynaptic neurons. Two forms of signals are required for functional synapse formation during development: activity-independent and activity-dependent signals. Usually, initial synaptic differentiation is regarded as activity-independent steps, whereas a period of activity-dependent synapse maturation shapes the ultimate structure of neural circuits4–7. During synapse maturation, activity-dependent signals either stabilize or eliminate axons and further maturate selected synapses to establish appropriate synaptic connections8–12. Thus, activity-dependent mechanisms are required for the structural refinement of neural circuits, to match pre- and postsynaptic function, and for the final arrangement of the appropriate synaptic map11–14. While synapse stabilization/destabilization and maturation are clearly activity-dependent, little is known about molecular mechanisms underlying them. Defects in activity-dependent synapse maturation in the hippocampus have been implicated in various neurodevelopmental disorders, including schizophrenia and autism1–3. Therefore, the understanding of the molecules and manner by which hippocampal circuits are established by neural activity should yield novel insights into both the etiology and treatment of these devastating disorders.

To understand the molecular mechanisms of synapse formation, we have performed an unbiased search for molecules that promote differentiation of axons into presynaptic nerve terminals. Using the ability to cluster synaptic vesicles in cultured motor neurons as a bioassay, we have purified molecules that can promote differentiation of axons into presynaptic nerve terminals from developing brains and identified two molecules, FGF22 (fibroblast growth factor 22)15 and SIRPα (signal regulatory protein α)16, as such presynaptic organizers. We have shown that FGF22 and its close relative FGF7 are selectively involved in the initial organization of excitatory (glutamatergic) and inhibitory (GABAergic) synapses, respectively, in the hippocampus17. The other molecule, SIRPα, is a transmembrane immunoglobulin superfamily member that is involved in various hematopoietic cell functions18–20, but little is known about its roles in the brain. We therefore investigated the role, mechanism, and impact of SIRPα-dependent synapse formation in the brain.

Here we show that: 1) Target-derived molecules FGF22 and SIRPα sequentially organize presynaptic terminals; 2) SIRPα is necessary for presynaptic maturation, but not for induction or maintenance, in the hippocampus in vivo; 3) SIRPα drives presynaptic maturation in an activity-dependent manner; 4) Activity cleaves the ectodomain of SIRPα, and this cleavage is required for SIRPα’s presynaptic effects; 5) Calcium, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) mediate SIRPα cleavage; 6) CD47 is SIRPα’s presynaptic receptor; and 7) SIRPα has a significant impact on synaptic function and plasticity. These results indicate that ectodomain shedding of SIRPα is an activity-dependent mechanism allowing pre- and postsynaptic terminals to communicate for the maturation of functional synapses.

RESULTS

Distinct expression of FGF and SIRPα during synaptogenesis

We first compared the expression patterns of SIRPα and FGFs in the hippocampus during synapse formation. In situ hybridization experiments with mouse brain sections showed little Sirpα mRNA expression in hippocampal neurons at postnatal day 8 (P8; Fig. 1a), an early stage of synapse formation21,22, but substantially higher expression at P21, a late stage of synapse formation. Western blotting confirmed a robust increase in the amount of SIRPα proteins from P8 to P21 (Fig. 1b). This expression pattern is in contrast to the patterns of Fgf22 and Fgf7 mRNA, which were highly expressed at P817, but not at P21 (Supplementary Fig. 1). These results suggest that FGFs and SIRPα are involved in the early and late stages of synapse formation, respectively, in the hippocampus.

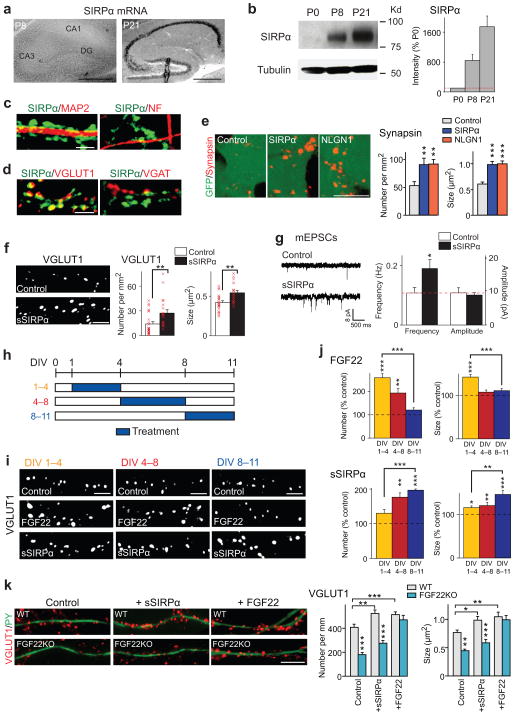

Figure 1. FGF22 and SIRPα promote the early or late stage of glutamatergic presynaptic differentiation.

(a) In situ hybridization for Sirpα in the hippocampus during synapse formation (positive signals in black). Sirpα mRNA is highly expressed at P21, the time for synapse maturation, but not at P8, the time for initial synapse differentiation. Reproduced three times.

(b) Western blotting for the SIRPα protein (tubulin as control) in the hippocampus. The amount of SIRPα significantly increases from P8 to P21. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Figure 10.

(c,d) Hippocampal cultures at DIV11 were stained with the antibodies indicated. (c) SIRPα proteins are abundant on MAP2-positive dendrites but not on neurofilament (NF)-positive axons.(d) SIRPα is concentrated at VGLUT1-postive glutamatergic synapses but not at VGAT-positive GABAergic synapses. Reproduced five times.

(e) HEK cells expressing SIRPα, neuroligin1 (NLGN1), or control HEK cells (labeled with GFP) were co-cultured with hippocampal neurons for 2 days and stained for synapsin. The synapsin puncta formed on HEK cells expressing SIRPα are significantly more dense and larger than those formed on control HEK cells and are comparable to the ones on HEK cells expressing NLGN1. Data are from 24/23/22 fields from 5 cultures.

(f,g) Recombinant soluble SIRPα (sSIRPα) was applied to hippocampal cultures from DIV1–11.(f) sSIRPα treatment significantly increases the number (x 1,000 puncta per mm2) and size of VGLUT1 puncta as compared to PBS control (n = 57 fields from 5 cultures). (g) Representative traces and summary data of whole-cell recordings of mEPSCs from control and sSIRPα-treated hippocampal neurons. mEPSC frequency, but not amplitude, increases by sSIRPα treatment. (n = 57/63 cells from 5 cultures).

(h) Schematic timeline of the experiment shown in (i,j). Cultured hippocampal cells were treated with FGF22 or sSIRPα from DIV1–4 (beginning of synapse formation), DIV4–8 (middle of synapse formation), or DIV8–11 (ending of synapse formation). All cultures were fixed on DIV11.

(i) Staining of hippocampal cultures for VGLUT1 after treatment with FGF22 or sSIRPα as shown in (h).

(j) Numbers and sizes of VGLUT1 puncta after treatment on DIV1–4, DIV4–8, or DIV8–11. FGF22 treatment is most effective at increasing VGLUT1 clustering when incubated from DIV1–4, while sSIRPα is most effective when incubated from DIV8–11. Data are shown as percentage of PBS control and from 32/43/40/34/27/26 fields from 5 cultures.

(k) sSIRPα or FGF22 was applied to hippocampal cultures prepared from WT or FGF22KO mice, and the cultures were stained for VGLUT1 and Py, which labels dendrites of CA3 pyramidal neurons. Fewer and smaller VGLUT1 puncta were on CA3 neurons in FGF22KO cultures relative to WT cultures; the defects were rescued by the application of FGF22, but not by sSIRPα. n = 19/23/25/25/17/23 neurites from 3 cultures.

Bars in the graphs are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001 (here and in subsequent figures) by Student’s t-test (f,g) or by ANOVA followed by Tukey test (e,j,k). Scale bars, 500 μm (a), 10 μm (e,k), and 5 μm (others).

We next examined the localization of SIRPα in hippocampal neurons. Biochemical fractionation experiments revealed that SIRPα is abundant in the synaptic membrane fraction, indicating that SIRPα is a synaptic molecule. Notably, it was most enriched in the extra-junctional fraction (Supplementary Fig. 2), which is similar to some of other synaptogenic molecules including EphB223. Immunostaining of cultured hippocampal neurons showed that SIRPα was preferentially localized at MAP2-positive dendrites relative to neurofilament-positive axons (Fig. 1c). In dendrites, SIRPα was concentrated at excitatory synapses: it was co-localized (~75%) with vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGLUT1), a marker for glutamatergic presynaptic terminals, but showed little co-localization (~13%) with vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT), a marker for GABAergic presynaptic terminals (Fig. 1d). These results suggest that SIRPα is localized in dendrites at glutamatergic synapses (i.e., postsynaptic) and may serve as a target-derived glutamatergic presynaptic organizer in the hippocampus.

SIRPα promotes glutamatergic presynaptic differentiation

To address whether SIRPα can promote presynaptic differentiation of hippocampal neurons, we examined the effect that SIRPα has on synaptic vesicle clustering using a co-culture system24, where neurons are co-cultured with HEK cells. The number and size of synapsin puncta formed on HEK cells expressing SIRPα were significantly larger than those on control HEK cells (Fig. 1e). SIRPα’s presynaptic effects were comparable to those of neuroligin1, a well-characterized synaptogenic molecule, indicating that SIRPα is a synaptogenic molecule that can promote synaptic vesicle clustering in hippocampal neurons.

We then examined whether SIRPα can organize glutamatergic presynaptic differentiation. For this, we prepared the extracellular portion of SIRPα16 (soluble SIRPα – sSIRPα) and bath-applied it (2 nM) to the media of cultured hippocampal neurons for 10 days. sSIRPα significantly increased the number and size of VGLUT1 puncta (Fig. 1f). Furthermore, SIRPα increased the number and size of bassoon puncta, suggesting that SIRPα organizes active zones as well (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Electrophysiological recordings indicated that sSIRPα increased the frequency, but not the amplitude, of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs; Fig. 1g), consistent with an increase in synaptic contacts. sSIRPα did not significantly affect dendrite/axon differentiation or the clustering of PSD95, a postsynaptic scaffolding protein at glutamatergic synapses (Supplementary Fig. 3b,c), but did increase the colocalization between VGLUT1 and PSD95 (Supplementary Fig. 3c). These results indicate that SIRPα can specifically promote presynaptic differentiation of glutamatergic synapses in hippocampal neurons.

FGF22 and SIRPα promote distinct stages of synaptogenesis

Based on the developmentally different expression of Fgf22 and Sirpα mRNAs in the hippocampus, we hypothesized that FGF22 and SIRPα are preferentially involved in the early and late stages of glutamatergic synapse formation, respectively. To test this idea, we performed time course experiments using cultured hippocampal neurons. In our hippocampal cultures, glutamatergic synapse formation starts around days in vitro (DIV) 3 and slows down around DIV1217. To determine the time during which FGF22 and SIRPα are most effective at promoting presynaptic differentiation, we cultured hippocampal neurons and applied recombinant FGF22 or sSIRPα during three different periods: DIV1–DIV4, DIV4–DIV8, or DIV8–DIV11, which corresponds to the beginning, middle, and ending of synapse formation, respectively (Fig. 1h). All cultures were stained for VGLUT1 at DIV11. We found that FGF22 treatment was most effective at increasing the number and size of VGLUT1 puncta when applied from DIV1–4 (Fig. 1i,j and Supplementary Fig. 4), consistent with an early role in synapse development. In contrast, sSIRPα treatment increased the number and size of VGLUT1 puncta most prominently when it was applied from DIV8–11. These results support the notion that FGF22 and SIRPα are presynaptic organizing molecules with temporally distinct roles during synapse formation, with FGF22 in early and SIRPα in late stages of synapse formation.

To further show that FGF22 and SIRPα have distinct roles in presynaptic differentiation, we cultured FGF22-deficient neurons17 and examined whether SIRPα can rescue their synaptic defects. There were fewer and smaller VGLUT1 puncta on CA3 neurons in FGF22-deficient cultures relative to wild type cultures. These presynaptic defects were rescued by the application of FGF22, but not by SIRPα, to cultures (Fig. 1k). These results suggest that although both FGF22 and SIRPα can induce presynaptic differentiation, their specific roles in presynaptic differentiation are different.

SIRPα is required for presynaptic maturation in vivo

In FGF22−/− mice, the differentiation of glutamatergic nerve terminals in the hippocampus is impaired early in synapse development at P817. To identify the developmental stages during which SIRPα is critical for synapse formation in vivo, we generated a conditional SIRPα knockout mouse (Supplementary Fig. 5a). To temporally control the expression of SIRPα, floxed SIRPα mice were mated with actin-Cre-ER mice25 and injected with tamoxifen at different postnatal days to induce Cre-mediated excision of the Sirpα gene. Tamoxifen injections effectively inactivated SIRPα in the hippocampus of these mice as confirmed by immunostaining for SIRPα (Supplementary Fig. 5b). In the rodent hippocampus, synapse formation starts in the first postnatal week21,22. After their initial formation, synapses are then refined in an activity-dependent manner: effective synapses are stabilized and mature, while inactive contacts are destabilized and eliminated4–10. We have previously shown that activity-dependent synapse refinement in the hippocampus occurs between P15 and P2526. Thus, we chose three time periods corresponding to three different stages of synapse development to inactivate SIRPα: P0–P14 (initial synapse differentiation); P15–P29 (synapse maturation); and P30–P44 (synapse maintenance). When we injected SIRPα conditional knockout mice with tamoxifen at P0 and stained their hippocampi for VGLUT1 at P14, the intensity of VGLUT1 staining was not significantly different in the SIRPα−/− mice as compared to control (Fig. 2a), indicating that contrary to FGF2217, SIRPα is not critical for initial synapse development. In contrast, when we injected tamoxifen at P15 and analyzed at P29, the intensity of VGLUT1 staining was significantly reduced in the knockout hippocampus as compared to controls (Fig. 2b). Further analyses revealed that the size and intensity of each VGLUT1 punctum were decreased in SIRPα−/− mice. In addition to VGLUT1, the intensity of bassoon staining, a marker for active zones, was also decreased in the knockout mice relative to control mice (Fig. 2c). These results suggest that SIRPα inactivation significantly affects the maturation of presynaptic terminals. Finally, when we injected tamoxifen at P30 and analyzed at P44, the intensity of VGLUT1 staining was not significantly different in the knockout mice as compared to control (Fig. 2d). These results demonstrate that SIRPα is critical for presynaptic maturation (P15–P29) but is not necessary for initial synapse development or synapse maintenance in vivo.

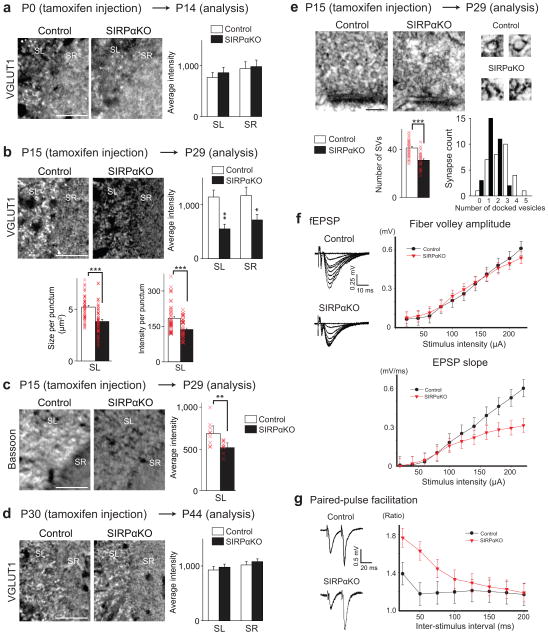

Figure 2. SIRPα is required for the maturation, but not induction or maintenance, of excitatory presynaptic terminals in the hippocampus in vivo.

(a–d) SIRPα was inactivated around the time of initial synapse differentiation (P0–P14; a), synapse maturation (P15–P29; b,c), or synapse maintenance (P30–P44; d) by tamoxifen injections into conditional SIRPαKO mice. Control animals also received tamoxifen. Hippocampal sections from the control and SIRPαKO mice were stained for VGLUT1 (a,b,d) or bassoon (c). Images are from CA3 (positive signals in white). SL, stratum lucidum; SR, stratum radiatum. Graphs show the measurements of the relative intensity of VGLUT1 or bassoon staining (% control). (a) Mice were injected with tamoxifen at P0 and analyzed at P14. No significant difference in the VGLUT1 staining intensity between control and SIRPαKO at this time period. (b,c) Mice were injected with tamoxifen at P15 and analyzed at P29. The VGLUT1 (b) and bassoon (c) staining intensities are significantly decreased in SIRPαKO mice relative to control. Quantifications of the average size and intensity of VGLUT1 puncta are also shown in (b). (d) Mice were injected with tamoxifen at P30 and analyzed at P44. No significant difference between control and SIRPαKO at this time period. Staining data are from 12/20 sections from 3/5 mice.

(e) Electron microscopic analysis of asymmetric (excitatory) synapses in CA3 of P29 mice injected with tamoxifen at P15. High magnification views of synaptic vesicles (SVs) are shown on the right. The numbers of SVs within 400 nm of the active zone and the numbers of docked vesicles are quantified. Significantly fewer SVs and docked vesicles are found in asymmetric synapses in SIRPαKO mice relative to control. Data are from 30 synapses from 3 mice. Student’s t-test (a–e). Scale bars, 50 μm (a) and 100 nm (e).

(f) Evoked fEPSPs were recorded in acute slices from CA1 of SIRPαKO mice and control littermates (tamoxifen injections at P15, analyses at P29). Sample traces of fEPSP recordings are shown. In input-output curves (right), fEPSP slope, but not fiber volley amplitude, is significantly decreased in SIRPαKO mice relative to control littermates (p < 0.001 by two-way ANOVA; n = 9/13 cells from 4 mice).

(g) Paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) across a range of inter-stimulus intervals for evoked EPSCs from SIRPαKO mice and control littermates. PPF is significantly enhanced in SIRPαKO mice (p < 0.001 by two-way ANOVA; n = 11/15 cells from 4 mice).

We also performed a series of experiments to examine whether the inactivation of SIRPα primarily affects presynaptic maturation. In the SIRPα−/− mice with tamoxifen injected at P15, the hippocampus looked anatomically normal, and the fate of the cells in the hippocampus appeared to be unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 6a–d). In addition, the clustering of PSD95 was not significantly decreased in SIRPα−/− as compared to control mice (Supplementary Fig. 6e). Thus, SIRPα appears to be primarily involved in presynaptic maturation in the hippocampus in vivo. Consistent with its expression pattern (Fig. 1a and data not shown), presynaptic maturation in SIRPα−/− mice was impaired throughout the hippocampus (Supplementary Fig. 6f), as well as in the cerebellum. The presynaptic defects in SIRPα−/− mice were still detected at P130 (Supplementary Fig. 6g), suggesting that SIRPα inactivation prevents presynaptic maturation rather than just delaying it.

To further confirm the role of SIRPα in presynaptic maturation, we examined the ultrastructure of excitatory (asymmetric) synapses formed in the hippocampus in P29 SIRPα−/− mice injected with tamoxifen at P15 (Fig. 2e). We found significantly fewer synaptic vesicles and fewer docked synaptic vesicles in the asymmetric synapse in SIRPα−/− mice relative to control. In addition, the shape of synaptic vesicles in SIRPα−/− mice looked irregular compared to control.

Diminished transmitter release probability in SIRPα−/− mice

To directly address the functional state of synapses in SIRPα−/− mice, we recorded evoked field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) at CA3-CA1 synapses in acute hippocampal slices (tamoxifen injections at P15, analyses at ~P29). Input-output curves of fEPSP slope were strongly diminished in SIRPα−/− mice relative to control littermates (Fig. 2f), whereas fiber volley amplitude (reflecting the number of axons firing to each stimulation) was unaffected, indicating that synaptic transmission is impaired in the absence of SIRPα.

Moreover, paired-pulse facilitation was dramatically increased in SIRPα−/− mice relative to controls (Fig. 2g), suggesting that neurotransmitter release probability is diminished in the knockout mice. SIRPα−/− neurons therefore have significant defects in excitatory presynaptic function. Taken together, the histological and electrophysiological results with SIRPα−/− mice demonstrate that SIRPα is necessary for the maturation, but not induction or maintenance, of excitatory presynaptic terminals in the hippocampus in vivo.

Presynaptic maturation by SIRPα requires neural activity

During the maturation stage of synapse formation, activity-dependent signals either stabilize or destabilize the synapses to establish efficient synaptic connections. Therefore, we hypothesized that SIRPα contributes to mechanisms that stabilize and promote maturation of presynaptic terminals in response to neural activity.

To test this idea, we examined whether the presynaptic effects of SIRPα require neural activity. When SIRPα was transfected into cultured hippocampal neurons, the size of VGLUT1 puncta was significantly increased on the dendrites of SIRPα-expressing neurons relative to control (Fig. 3a,b). This SIRPα-dependent increase in VGLUT1 clustering was completely blocked by suppressing neural activity with the sodium channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM) or by suppressing synaptic transmission with a cocktail of neurotransmitter receptor inhibitors (50 μM APV, 10 μM CNQX, 50 μM bicuculline). These data suggest that neural activity is critical for SIRPα-dependent presynaptic maturation.

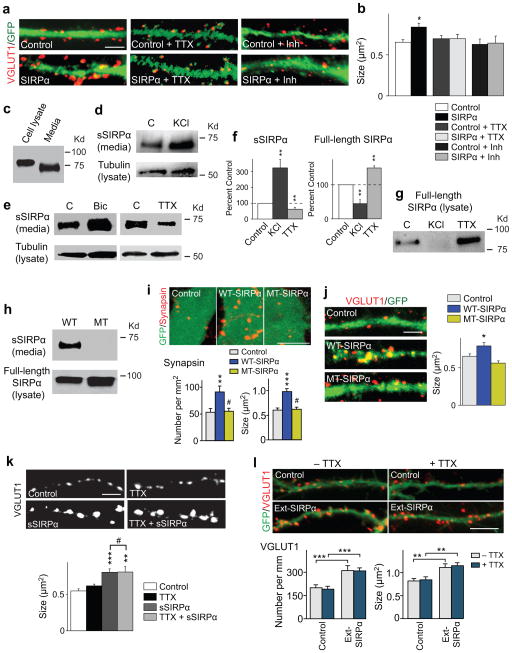

Figure 3. Cleavage of the extracellular domain of SIRPα is activity-dependent and is necessary for SIRPα-dependent presynaptic maturation.

(a,b) Hippocampal neurons were transfected with a GFP plasmid (Control) or SIRPα and GFP plasmids (SIRPα) at DIV4. TTX or a cocktail of inhibitors for neurotransmitter receptors (APV, CNQX, bicuculline) was applied from DIV5. Cultures were stained for VGLUT1 on DIV13. VGLUT1 clustering on the dendrites of SIRPα-transfected neurons is increased in size as compared to control, but addition of TTX or the inhibitor cocktail prevents this increase. n = 10 neurites from 3 cultures.

(c) Hippocampal neurons were cultured for 11 days. Media and cell lysates were assayed for SIRPα. Reproduced five times.

(d–g) Hippocampal neurons were cultured for 10–12 days and then incubated with KCl, bicuculline, or TTX for 1–3 days. Media was collected and assayed for the amount of secreted SIRPα (sSIRPα) by immunoprecipitation followed by Western blotting (d,e). Cell lysates were also prepared and assayed for tubulin (d,e) and full-length SIRPα remaining on the cell (g) by Western blotting. In all conditions tested, tubulin levels are similar among the cell lysates. (d) Addition of KCl to activate neurons increases the amount of secreted SIRPα in the media as compared to control. (e) Bicuculline increases the amount of sSIRPα in the media, while TTX decreases it. (f) Quantification of the band intensity from results such as those shown in (d,e,g). Intensities were normalized against the intensity of the control band. n = 5/3 blots from 5/3 cultures. (g) In the cell lysate, the amount of full-length SIRPα is decreased in KCl-treated cultures and increased in TTX-treated cultures.

(h) Verification of cleavage-resistant mutant SIRPα. HEK cells were transfected with the wild-type SIRPα or cleavage-resistant mutant SIRPα (MT) plasmid for 2 days. Media and cell lysates were assayed for sSIRPα or full-length SIRPα. MT-SIRPα shows no release of sSIRPα. Reproduced three times.

(i) HEK cells expressing WT- or MT-SIRPα and control HEK cells (labeled with GFP) were co-cultured with hippocampal neurons for 2 days and stained for synapsin. MT-SIRPα does not increase the number and size of synapsin puncta. Data are from 24/24/33 fields from at 5 cultures.

(j) Hippocampal neurons were transfected with the GFP plasmid (Control) or the WT- or MT-SIRPα plasmid together with the GFP plasmid at DIV4 and stained for VGLUT1 at DIV13. VGLUT1 puncta on the dendrites of WT-SIRPα-transfected neurons, but not on those of MT-SIRPα-transfected neurons, are increased in size as compared to control. n = 23 neurites from 3 cultures.

(k) Presynaptic maturation induced by soluble SIRPα is not dependent on neural activity. Hippocampal neurons were treated with a bath application of sSIRPα and/or TTX from DIV1, and stained for VGLUT1 at DIV13. sSIRPα increases the size of VGLUT1 puncta, and adding TTX has no effect on the VGLUT1 clustering induced by sSIRPα. n = 13 fields from 3 cultures. (l) Hippocampal neurons were transfected with the GFP plasmid (Control) or the Ext-SIRPα and GFP plasmids (Ext-SIRPα = secretable SIRPα) at DIV4. TTX was applied from DIV5. Cultures were stained for VGLUT1 on DIV13. VGLUT1 clustering on the dendrites of Ext-SIRPα-transfected neurons is increased in number and size as compared to control, and addition of TTX has no effect on this increase. n = 26/23/21/24 neurites from 3 cultures.

Student’s t-test (b,f) or ANOVA followed by Tukey test (i–l). #: not significant. Scale bars, 10 μm (i,l), 5 μm (a,j,k).

Neural activity cleaves the extracellular domain of SIRPα

What are the mechanisms by which neural activity controls SIRPα-dependent presynaptic maturation? A clue came from our initial identification of SIRPα as a presynaptic organizing molecule – the SIRPα protein we identified from the brain extract was the extracellular portion of SIRPα16. In fact, from cultured neurons, we were able to collect secreted SIRPα in the media, and its molecular weight is smaller than full-length SIRPα expressed in neurons (Fig. 3c). In addition, we detected a short fragment of SIRPα containing its C-terminal domain (~16 Kd; size corresponding to the intracellular domain) in the synaptic membrane fraction (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, we hypothesized that the extracellular domain of SIRPα is cleaved by neural activity, and that this cleavage is required for its presynaptic effects (see Supplementary Fig. 7a).

To examine whether the extracellular domain of SIRPα is cleaved and released from hippocampal neurons in response to neural activity, we cultured hippocampal cells with either KCl (50 mM) to depolarize neurons, bicuculline (50 μM) to enhance endogenous network activity, or TTX (1 μM) to suppress network activity. We then collected media and assessed the amount of cleaved and released SIRPα by immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot. KCl and bicuculline treatments significantly increased the amount of released SIRPα in media as compared to untreated control (Fig. 3d–f), while TTX treatment significantly decreased the amount of cleaved SIRPα in the media, indicating that the SIRPα ectodomain is released by neural activation. These effects were not due to altered cell numbers, as the amount of tubulin in the cell lysate was not altered by any treatment condition. In addition, the amount of full-length SIRPα remaining on the cell was decreased in KCl-treated cultures, and increased in TTX-treated cultures (Fig. 3f,g), consistent with an increase or a decrease in SIRPα cleavage by KCl or TTX treatment, respectively.

Shedding of SIRPα is necessary for presynaptic maturation

We then investigated whether the cleavage of the extracellular domain of SIRPα is required for presynaptic maturation mediated by SIRPα. For this, we prepared a mutant form of SIRPα (MT-SIRPα) that is resistant to ectodomain shedding (Fig. 3h). In the HEK cell-hippocampal neuron co-culture system (see Fig. 1e), the number and size of synapsin puncta formed on HEK cells expressing MT-SIRPα were similar to those on control HEK cells (Fig. 3i), indicating that MT-SIRPα cannot promote synaptic vesicle clustering in hippocampal neurons.

We next transfected cultured hippocampal neurons with wild-type SIRPα (WT-SIRPα) or MT-SIRPα. The localization of MT-SIRPα was similar to that of WT-SIRPα (Supplementary Fig. 7b,c). Overexpression of WT-SIRPα led to an increase in the size of VGLUT1 puncta on the transfected neurons; however, overexpression of MT-SIRPα failed to do so (Fig. 3j). These results indicate that shedding-resistant SIRPα cannot promote presynaptic maturation both in co-culture and neuronal culture, suggesting that the cleavage and secretion of the SIRPα ectodomain are necessary for its presynaptic effects.

Neural activity is responsible for SIRPα cleavage

If neural activity is responsible for cleaving SIRPα, suppressing neural activity should inhibit the presynaptic effect of full-length SIRPα (Fig. 3a,b) but not that of soluble SIRPα (sSIRPα). To test this idea, we cultured hippocampal neurons with sSIRPα with or without TTX. Application of sSIRPα increased the size of VGLUT1 puncta, and unlike what was observed with full-length SIRPα, this effect was completely resistant to TTX (Fig. 3k). Thus, after cleavage, presynaptic maturation by SIRPα is no longer dependent on neural activity.

To exclude the possibility that SIRPα is subjected to constitutive cleavage in neurons followed by activity-dependent secretion of its cleaved product, we performed an experiment with a secretable form of SIRPα, which contains only the extracellular domain of SIRPα (Ext-SIRPα; the construct used to prepare sSIRPα). When transfected into cultured neurons, Ext-SIRPα efficiently induced maturation of glutamatergic presynaptic terminals on the Ext-SIRPα expressing neurons (Fig. 3l). This presynaptic effect was not inhibited by TTX application, indicating that neural activity does not play important roles in the secretion of Ext-SIRPα. These results are consistent with the notion that neural activity is responsible for cleaving, and not secretion of, the extracellular domain of SIRPα.

CaMK and MMP mediate activity-dependent SIRPα cleavage

We further investigated the signaling pathway that is involved in activity-dependent SIRPα cleavage. CaMK is a major signaling molecule at synapses27, prompting us to explore the possibility that CaMK contributes to SIRPα cleavage. Consistent with this hypothesis, treatment of hippocampal cultures with CaMK inhibitors, KN62 or KN93 (5 μM), significantly decreased the amount of cleaved SIRPα in the media (Fig. 4a). We next examined the effects of a CaMK inhibitor (KN62) and a calcium channel blocker (nifedipine; 10 μM) on activity-dependent cleavage of SIRPα. Both inhibitors suppressed KCl-induced SIRPα cleavage (Fig. 4b), suggesting that neural activity-dependent calcium entry followed by CaMK activation plays important roles in the ectodomain shedding of SIRPα.

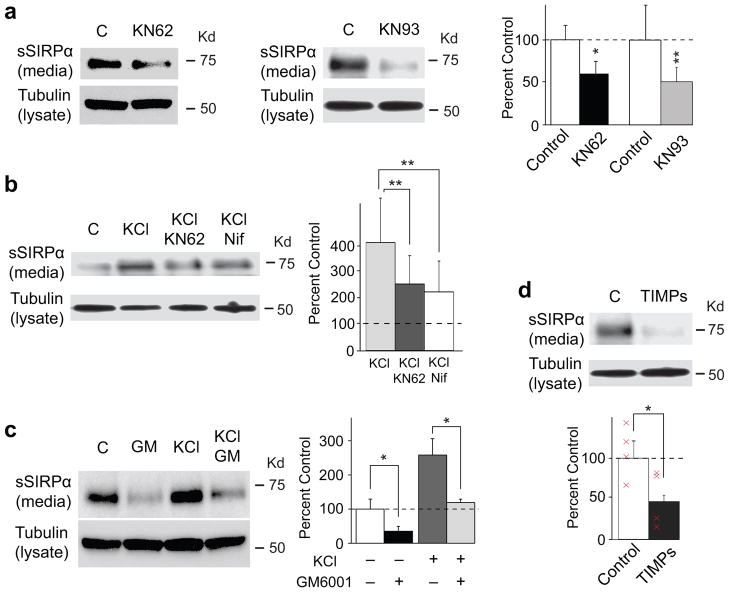

Figure 4. SIRPα-dependent presynaptic maturation involves calcium channel, CaMK, and MMP.

(a–d) Hippocampal neurons were cultured for 10–12 days and then incubated with a calcium channel blocker - nifedipine, CaMK inhibitors - KN62 or KN93, or MMP inhibitors - GM6001 or TIMPs, in the presence or absence of KCl for 1–3 days. Media was collected and assayed for the amount of secreted SIRPα. Cell lysates were assayed for tubulin. Quantification of the sSIRPα band intensity is shown in the graphs (normalized against control). Nifedipine, KN62, KN93, GM6001, and TIMPs effectively decrease the amount of sSIRPα found in the media (Student’s t-test). n = 4 blots from 4 cultures.

We then characterized the proteases that cleave the extracellular domain of SIRPα. MMPs are zinc-dependent endopeptidases that cleave extracellular molecules and are implicated in synaptic function28. We found that incubation of hippocampal neurons with MMP inhibitors, GM6001 (10 μM) or TIMP (0.5 μg/ml), markedly inhibited SIRPα shedding, including the augmented cleavage induced by KCl (Fig. 4c,d). These results suggest that calcium, CaMK, and MMP are involved in the activity-dependent shedding of SIRPα from hippocampal neurons.

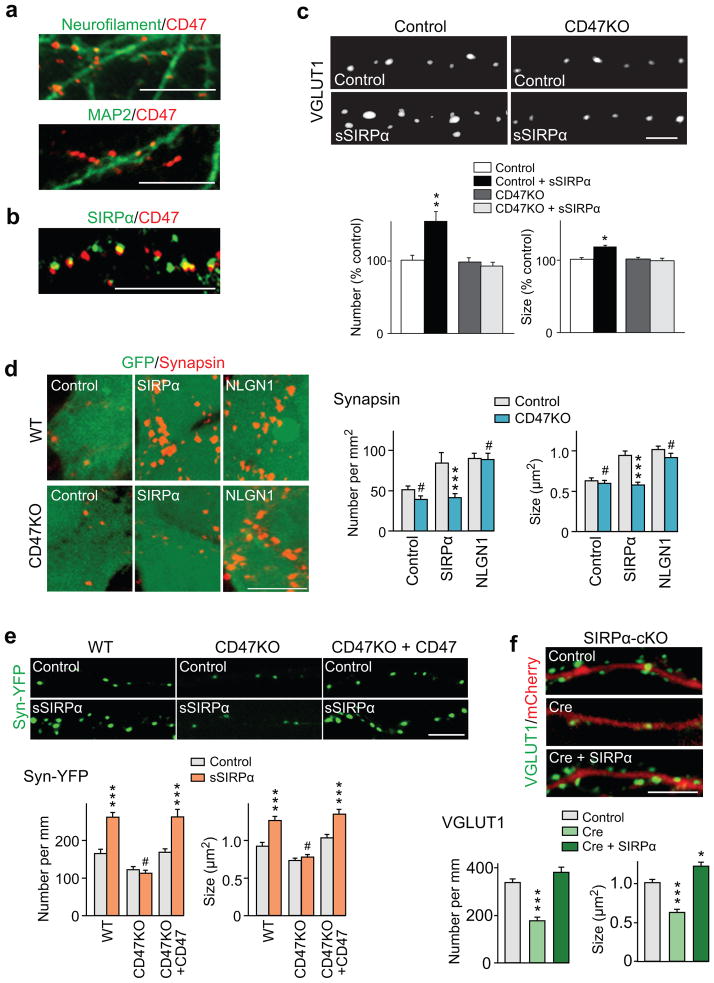

CD47 is the presynaptic receptor for SIRPα

Since our data indicate that the shed SIRPα ectodomain promotes presynaptic maturation, we next examined the identity of its presynaptic receptor. We asked whether CD47, a receptor for SIRPα in hematopoietic cells18–20, mediates the presynaptic effects of SIRPα. Immunostaining experiments showed that CD47 puncta were abundant in neurofilament-positive axons and not in MAP2-positve dendrites (Fig. 5a) and that CD47 co-localized with SIRPα (Fig. 5b), consistent with the idea that CD47 serves as a presynaptic receptor for SIRPα. We then used CD47−/− neurons29 to determine if CD47 mediates SIRPα’s effects. CD47−/− neurons extended axons and dendrites normally (Supplementary Fig. 8), but did not increase the number and size of VGLUT1 puncta in response to sSIRPα application (Fig. 5c). The following two experiments suggest that CD47 acts as a presynaptic receptor for SIRPα: i) HEK cells expressing SIRPα, which can induce presynaptic differentiation in co-cultured WT hippocampal neurons, failed to do so in co-cultured CD47−/− neurons; while neuroligin1 was able to induce presynaptic differentiation in both WT and CD47−/− neurons (Fig. 5d), and ii) CD47−/− neurons do not respond to sSIRPα application to induce presynaptic differentiation as assessed by synaptophysin-YFP clustering, but the responsiveness is restored by presynaptic expression of CD47 (Fig. 5e).

Figure 5. CD47 is the presynaptic receptor for SIRPα-mediated presynaptic maturation.

(a,b) Hippocampal neurons were stained for CD47 together with neurofilament, MAP2 or SIRPα. CD47 puncta are abundant in neurofilament-positive axons and not in MAP2-positve dendrites (a) and co-localized with SIRPα (b). Reproduced five times.

(c) Hippocampal neurons prepared from CD47KO mice and control littermates were treated with sSIRPα and stained for VGLUT1. sSIRPα does not increase the number and size of VGLUT1 puncta in CD47KO neurons. n = 80/93/102/108 fields from 4 cultures.

(d) HEK cells expressing SIRPα, neuroligin1, or control HEK cells (labeled with GFP) were co-cultured with hippocampal neurons prepared from WT or CD47KO mice for 2 days and stained for synapsin. HEK cells expressing SIRPα induce presynaptic differentiation in co-cultured WT hippocampal neurons, but fail to do so in co-cultured CD47KO neurons. HEK cells expressing neuroligin1 induce presynaptic differentiation in both WT and CD47KO neurons. Graphs show quantification of synapsin puncta number and size. Data are from 38/34/34/35/42/40 fields from 5 cultures.

(e) Presynaptic expression of CD47 restores responsiveness to sSIRPα in CD47KO neurons. Hippocampal neurons prepared from WT or CD47KO mice were transfected with the synaptophysin-YFP plasmid or with the synaptophysin-YFP and CD47 plasmids. Cultures were treated with sSIRPα, and presynaptic differentiation of transfected neurons was assessed by synaptophysin-YFP clustering. sSIRPα does not increase the number and size of synaptophysin-YFP puncta in CD47KO neurons, but introduction of CD47 restores responsiveness to sSIRPα. n = 33/37/33/35/37/36 neurites from 3 cultures.

(f) Postsynaptic expression of SIRPα rescues presynaptic defects in SIRPαKO neurons. Hippocampal neurons prepared from conditional SIRPαKO mice were transfected with an mCherry plasmid (control), Cre and mCherry plasmids (knockout) or Cre, mCherry and SIRPα plasmids (rescue) and stained for VGLUT1. Both the number and size of VGLUT1 puncta on mCherry-expressing dendrites were decreased in SIRPαKO relative to control, but postsynaptic expression of SIRPα rescues the defects. n = 41/33/36 neurites from 3 cultures.

Student’s t-test (c) or ANOVA followed by Tukey test (d–f). Scale bar, 5 μm (c), 10 μm (all others).

Finally, we confirmed that the source of SIRPα is postsynaptic: we found that presynaptic defects in SIRPα−/− neurons are rescued by postsynaptic expression of SIRPα (Fig. 5f). All together, these results strongly suggest that postsynaptic-derived SIRPα interacts with presynaptic CD47 to organize presynaptic maturation.

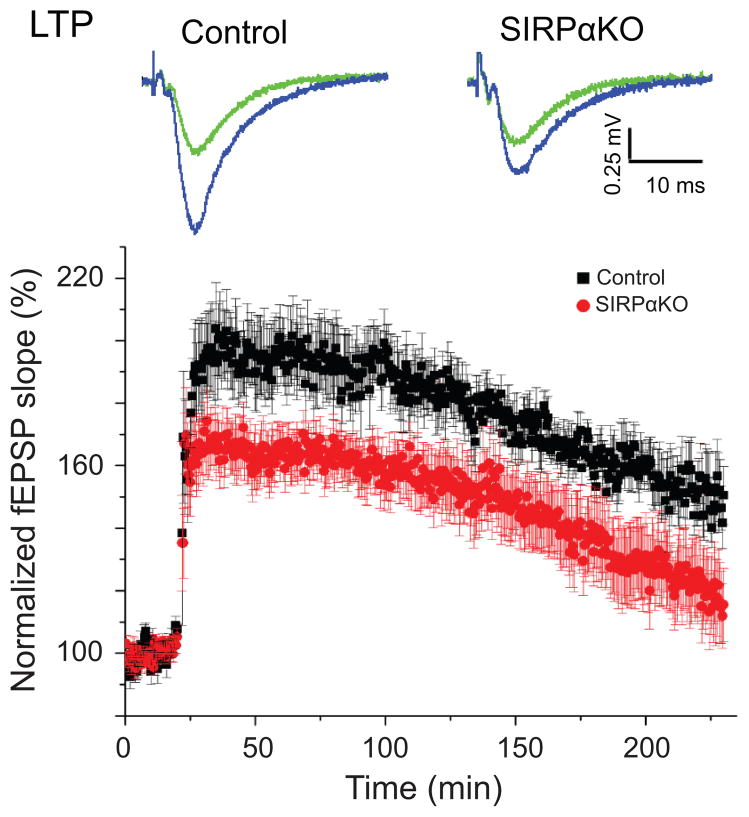

LTP is impaired in SIRPα−/− mice

What are the functional consequences of defects in SIRPα-dependent presynaptic maturation? To explore this question, we examined the impact of SIRPα-deficiency on activity-dependent synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. We found that long-term potentiation (LTP) is impaired at CA3–CA1 synapses in the hippocampus of SIRPα−/− mice (Fig. 6); of relevance, CD47−/− mice also show impaired LTP30. This is consistent with the altered presynaptic function in SIRPα−/− mice (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 9) and demonstrates that SIRPα-dependent synapse maturation has an enduring impact on long-lasting forms of plasticity in hippocampal circuits.

Figure 6. Impact of SIRPα-dependent presynaptic maturation on synaptic plasticity.

Hippocampal slices were prepared from SIRPαKO mice and control littermates and fEPSPs recorded at CA3–CA1 synapses. LTP was induced by high frequency stimulation (four trains of 1s, 100 Hz stimulations spaced by 30s intervals). LTP is significantly impaired in SIRPαKO mice (p < 0.05 by Student’s t-test at 1 hour after the LTP induction). n = 20/10 slices from 11/7 mice.

DISCUSSION

Activity-dependent synapse maturation is a critical step for the refinement of neural circuits and the establishment of the appropriate and efficient synaptic map in the brain. However, little is known about the molecular mechanisms that control this important aspect of synapse development. Here, we have uncovered a new process by which neural activity contributes to synapse maturation. From our results, we propose that after initial synaptic differentiation by molecules such as FGF2217, synaptic activity regulates extracellular domain cleavage of postsynaptic SIRPα through CaMK and MMP, and the released SIRPα ectodomain, in turn, promotes the maturation of the presynaptic terminal through CD47 (Supplementary Fig. 7a). SIRPα-dependent synapse maturation has a significant impact on synaptic function and plasticity, as demonstrated by impaired basal transmission, diminished neurotransmitter release probability, and impaired LTP in SIRPα−/− mice.

To date, there are several molecules that are implicated in presynaptic development, including neuroligins, SynCAMs, ephrins/Ephs, LRRTMs, NGLs, FGFs, Wnts, neurotrophins, Cblns, and thrombospondins5–7,31–33. Why are there multiple presynaptic organizers? We hypothesized that different presynaptic organizers are for the organization of different types of synapses (spatial specificity) and for the regulation of different stages of synapse formation (temporal specificity). As far as spatial specificity is concerned, we have previously shown that two FGFs, FGF22 and FGF7, are involved in the differentiation of two distinct types of synapses in vivo: FGF22 in excitatory and FGF7 in inhibitory17. Several presynaptic organizers such as neuroligin1, SynCAMs, Ephs, LRRTMs, and NGLs seem to be relatively specific to excitatory synapses, while others such as neuroligin2 and BDNF may be preferentially involved in inhibitory synapses. Thus, distinct presynaptic organizers indeed appear to be contributing to the organization of different synapses in the brain. As for temporal specificity, we here showed that in the hippocampus, FGF22 and SIRPα are important for two sequential stages of synapse formation, with FGF22 in initial synaptic differentiation and SIRPα in synapse maturation. Together, we propose that multiple spatially- and temporally-defined presynaptic organizers cooperate to organize specific and functional synaptic networks in the brain.

The role of SIRPα has been mainly studied in the immune system. Little is known about its function in the nervous system, but possible roles for SIRPα’s intracellular domain have been suggested: it promotes neurite outgrowth and enhances the effect of BDNF in culture20,34, and mice expressing mutant SIRPα that lacks the intracellular domain show prolonged immobility in the forced swim test35. We focused on the role of SIRPα’s extracellular domain: using hippocampal cultures and conditional SIRPα knockout mice, we showed that the extracellular domain of SIRPα serves as a target-derived presynaptic organizer in the hippocampus and is critical in the maturation stage of synapse formation in vitro and in vivo. SIRPα’s extracellular domain is cleaved in response to neural activity, acting as an activity-dependent, target-derived presynaptic organizer. Why does SIRPα need to be cleaved for presynaptic maturation? Cleavage may be necessary for the extracellular domain of SIRPα to bind to its presynaptic receptor, CD47. Crystal structure models of SIRPα and CD47 suggest that the extracellular region of SIRPα-CD47 complex is ~14 nm36,37. However, the cleft of excitatory synapses is ~25 nm, which may require the release of SIRPα ectodomain to bind to CD47. It will be also interesting to address the fate and roles of the SIRPα intracellular domain after cleavage.

Ectodomain shedding plays important roles in various processes including sperm-egg interaction, cell migration and adhesion, cell fate determination, wound healing, axon guidance, and immune responses38–40. Here we identified a novel role for ectodomain shedding: activity-dependent ectodomain shedding of SIRPα is involved in synapse maturation. Notably, while we were preparing our paper, two groups showed that activity-dependent cleavage of neuroligin1 is involved in synapse disassembly and negatively regulates synaptic function in a homeostatic manner41,42. In contrast, our results demonstrate that activity-dependent cleavage of SIRPα is a critical positive regulator of synapse maturation during synapse development to establish functional circuits. It is also noteworthy that the cleavages of both SIRPα and neuroligin1 involve common pathways, CaMK and MMP; yet, they have opposite effects at synapses. Thus, our results, together with the neuroligin results, significantly expand the role of activity-dependent shedding in controlling synapse maturation and function. How activity-dependent shedding of SIRPα and neuroligin1 cooperate/antagonize to regulate synapses is an interesting next question to address. Finally, since defects in activity-dependent synapse maturation in the hippocampus have been implicated in various neurological and psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and autism1–3, our results may help design strategies to prevent and treat such disorders.

ONLINE METHODS

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as described43 using digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes (Roche). The probes were generated by PCR from the 3′ untranslated regions15–17.

Primary neuronal cultures and transfection

Hippocampal cultures were prepared as described17. For immunostaining, hippocampal cells (1.5 × 104 to 4 × 104) were plated on glass coverslips (diameter 12 mm) coated with poly-D-lysine. Transfection was performed using the CalPhos Mammalian transfection kit (Clontech). For immunoprecipitation, hippocampal cells (3 × 105 to 5 × 105) were plated on poly-D-lysine-coated tissue culture dishes (diameter 35 mm). For co-culture experiments, HEK cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), and 24 hrs after transfection, they were dissociated and added onto cultured hippocampal neurons (DIV 8). Co-cultures were maintained for 48 hrs before fixation.

Knockout and transgenic mice

SIRPα knockout mice: A Sirpα genomic clone containing exon 1 (BAC clone 394B7; Invitrogen) was used to construct a targeting vector. A gene cassette composed of floxed full-length mouse Sirpα cDNA with SV40 intron-poly(A), EGFP-poly(A), and FRTed Tn5 neo44 was introduced into the first exon, deleting 71 nucleotides containing the start codon (Supplementary Fig. 5). The deletion disrupts the expression of the endogenous Sirpα gene but allows the expression of the inserted gene. Floxed SIRPα mice were generated by embryonic stem cell-based homologous recombination.

Actin-Cre-ER mice25 were mated with floxed SIRPα mice. Tamoxifen (100 μg to 1 mg) was injected at P0, P15, or P30 to induce the Cre recombinase-mediated excision of the Sirpα gene.

CD47 knockout mice29 were from W. Frazier (Washington University).

Mice used were C57/BL6 background. Both male and female mice were used in our experiments. We did not detect any significant differences between males and females. All animal care and use was in accordance with the institutional guidelines and approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals.

Immunohistochemistry

Cultures were fixed with methanol for 3 min at −20°C or with 1–4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min at 37°C and stained as described17. Mouse brains were fixed for 24 hours with 4% PFA in PBS. Sagittal sections of 20 μm thickness were cut in a cryostat and stained. For immunostaining for PSD95, mouse brains were fresh-frozen and sectioned. Sections were then fixed with methanol for 5 min at −20°C and stained. Dilutions and sources of antibodies are: anti-VGLUT1 (1:5,000; Millipore; AB5905), anti-PSD95 (1:250; NeuroMab; 75-028), anti-VGAT (1:1,500; Synaptic Systems; 131003), anti-MAP2 (1:3,000; Sigma-Aldrich; M4403), anti-neurofilament (1:1,000; Covance; SMI-312), anti-bassoon (1:500; Enzo Life Sciences; ADI-VAM-PS003), anti-GFP (1:1,000; Millipore; AB16901), anti-GFAP (1:500; Synaptic Systems; 173002), anti-NeuN (1:500; Millipore; MAB377), anti-calbindin (1:500; Sigma; C9848), anti-synapsin (1:2000; a kind gift from P. Greengard and A. Nairn, Rockefeller University), antibody Py (1:50; a kind gift from M. Webb and P.L. Woodhams)45, anti-CD47 (1:200; BD; miap301), polyclonal anti-SIRPα (against the SIRPα C-terminal domain; 1:200; Upstate Biotechnology; 06-729), and monoclonal anti-SIRPα (clone p84; 1:200; BD). Clone p84, which recognizes the extracellular domain of SIRPα and stains cell surface SIRPα, inhibits CD47-SIRPα interactions46, suggesting that the epitope of this antibody may be close to the CD47 binding site of SIRPα, which is its most distal Ig domain36.

Imaging and Quantification

Twelve-bit images at a resolution of 1,376 × 1,032 pixels were acquired on an Olympus BX61 epifluorescence microscope using 4× (2,226 × 1,670 μm images), 10× (890 × 668 μm), 20× (444 × 333 μm), and 40× (221 × 166 μm) objective lenses and an F-View II CCD Camera (Soft Imaging System). Alternatively, twelve-bit images at a 1,024 × 1,024 pixel resolution were acquired on a confocal microscope (Olympus, FV1000) using 40× objective lens with zoom 1.5× (211.8 × 211.8 μm). All images for each experiment were acquired with identical exposure time and detector gain.

For images of hippocampal sections stained for synaptic proteins, the average signal intensities of staining in the stratum lucidum and stratum radiatum layers were calculated with the MetaMorph software. The average signal intensity in the fimbria of the hippocampus was calculated and subtracted as the background. The intensity of the background was not significantly different between SIRPα−/− and control mice. For images of cultured neurons stained for synaptic proteins, the staining intensity of the dendritic shaft was calculated and subtracted as the background. Puncta size and intensity were quantified using the MetaMorph or ImageJ software17.

Electron microscopy

P15 SIRPα conditional knockout mice and littermate controls were injected with tamoxifen. At P29, the mice were perfused transcardially with Karnovsky’s fixative17. Hippocampi were removed, 1 mm cubes from the stratum radiatum layer of the CA3 region were dissected, and processed for electron microscopy. Thin sections (70 nm) were cut and observed with a Philips CM100 electron microscope at 60 kV. Digital images were captured with a Hamamatsu ORCA-HR digital camera system operated with Advanced Microscopy Techniques Corp. software.

Plasmid Constructs and Recombinant Proteins

A cDNA encoding mouse Sirpα (IMAGE: 5368250) was obtained from ATCC and cloned into the APtag5 expression vector (GenHunter) as described previously16. The mutant (shedding resistant) Sirpα47 was generated by PCR using the following primers: 5′-GGATATCGATTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGACCCACAACTGGAATGTCTTCATCG-3′ and 5′-AGGTATCGATATCCCCTTGATCACTCGAGTGG-3′. This replaced the juxtamembrane amino acids “SMQTFPGNNA” in the SIRPα protein with the FLAG epitope amino acids “DIDYKDDDDK”.

The expression plasmid for FGF22 was described previously17. The expression plasmid for Neuroligin1 was from G. Rudenko (University of Michigan), CD47 (IMAGE: 4187965) was from Open Biosystems, and Cre was from D. Goldman (University of Michigan).

Soluble SIRPα proteins (sSIRPα) were produced by transiently transfecting SIRPα extracellular-domain plasmids (= Ext-SIRPα) into HEK cells and purifying secreted SIRP proteins from culture media as described16. Recombinant FGF22 was from R&D Systems.

Immunoprecipitation

Hippocampal neurons were cultured for 10–12 days after which the media was replaced by new media (control), or media containing 50 mM KCl, 50 μM bicuculline, 1 μM TTX, 5 μM KN62, 5 μM KN93, 10 μM nifedipine, 10 μM GM6001, and/or 0.5 μg/ml TIMP’s (mixture of TIMP1 and TIMP2). After incubation for 1–3 days with these treatments, media and cells were collected. The media was precleared with Immobilized Protein-L (Pierce) and incubated with 1 μg of anti-SIRPα extracellular domain antibody for 4 hrs at 4°C. The immune complexes were precipitated with Protein-L and the immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blotting as described below to assess the amount of secreted SIRPα.

Western blotting

Cells, collected as described above, were lysed on ice for 1 hour in lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.0) with a protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche). Dissected hippocampi were lysed by homogenization in lysis buffer containing 1% Triton, 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4), and 150 mM NaCl with a protease inhibitor cocktail tablet. The immunoprecipitates and lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Equal amounts of lysate from each group were applied to the gel, as confirmed by testing the level of α-tubulin. Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane and probed using anti-SIRPα extracellular domain antibody (p84; 1:200; BD) and anti-α-tubulin antibody (1:5,000; Sigma; T6074). The proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare) and the band intensities were quantified with ImageJ software.

Synaptic protein fractionation

Fractionation protocol was adapted from a previous report48. 300–350 mg of cortex from P21 mice was homogenized in 1.5 ml of homogenization buffer (0.32 M Sucrose, 1 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CaCl2 and supplemented with protease inhibitor). Homogenate was then adjusted to 1.25 M Sucrose and 0.1 mM CaCl2 to a total of 5 ml. Homogenate was overlaid on 5 ml of 1 M Sucrose and spun at 100,000g for 3 hours at 4°C. Interface was collected and designated as synaptic membrane fraction (SPM). 500 μl of SPM was then added to 2 ml of 0.1 mM CaCl2 and 2.5 ml of 40 mM Tris, pH 6 with 2% Triton X-100 and placed on rocking platform for 20 min at 4°C. Sample was then spun at 35,000g for 20 minutes at 4°C and supernatant was collected as extra-junctional fraction. Pellet was air dried and resuspended in 1 ml of 0.1 mM CaCl2 and 1 ml of 40 mM Tris, pH 8 with 2% Triton X-100 and placed on rocking platform for 60 minutes. Resuspended pellets were then spun at 140,000g for 30 minutes at 4°C and supernatant was collected as presynaptic fraction. Insoluble fraction was resuspended in 1 ml 20 mM Tris pH 7.4 with 1% SDS and designated as postsynaptic fraction. Extra-junctional and presynaptic fractions were acetone precipitated and resuspended in 1 ml of 20 mM Tris pH 7.4 with 1% SDS. Synaptic membrane fraction and equivalent volumes of extra-junctional, presynaptic, and postsynaptic membrane fractions were then transferred to PVDF membrane and probed with anti-PSD95 antibody (1:500; NeuroMab; 75-028), anti-synaptotagmin antibody (1:100; Hybridoma Bank; mab48), and polyclonal anti-SIRPα antibody (1:500; Upstate; 06-729).

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings in cultures

Neurons were bathed in HEPES buffered saline (HBS), containing 119 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 30 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), supplemented with 1 μM TTX and 50 μM picrotoxin to isolate mEPSCs. Whole-cell internal solution included 100 mM gluconic acid, 0.2 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 0.3 mM GTP, and 40 mM HEPES (pH 7.2). Recording pipettes had a resistance of 4–6 MΩ. Recordings were made with an Axopatch 200B amplifier and collected with Clampex 8.0 (Molecular Devices). mEPSCs were analyzed using Minianalysis 6.0 (Synaptosoft).

Acute hippocampal slice preparation and field electrophysiology

Mice were decapitated and the hippocampi were isolated. Transverse slices (400 μm) were cut using a tissue chopper (Stoelting) and incubated at 25°C in a humidified chamber for at least 2 hours before recording. Slices were then transferred to a recording chamber, maintained at 27–28°C and continuously perfused at rate of 1.5 ml/min with oxygenated artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF). aCSF contained 119 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 26.3 mM NaHCO3, 11 mM glucose, 1.3 mM MgSO4, and 2.5 mM CaCl2. In most experiments (except Fig. 6), aCSF also contained 50 μM picrotoxin during recording. Picrotoxin was perfused for at least 15 min before data were collected. Recording electrodes were pulled from borosilicate capillary glass (1.7 mm o.d.; VWR International), filled with 3M NaCl, and placed in the stratum radiatum layer of CA1. fEPSPs were stimulated using cluster electrodes (FHC) also placed in the stratum radiatum of CA1. Current was delivered with an ISO-flex stimulus isolation unit (AMPI). Recordings were made with a MultiClamp 700B amplifier, collected and analyzed using Clampfit 10.2 (Molecular Devices). An input output curve was obtained for each slice by increasing the stimulus intensity from 0.02 to 0.25 mA. For paired-pulse experiments, the intensity was set at 0.2 mA, which was the maximum response size. To obtain the paired-pulse ratio, two pulses were delivered with an inter-pulse interval from 25–200 ms. For LTP experiments, the stimulus intensity was set so that the response size was 50% of maximum, and test stimuli were delivered every 30 s. After 20 min of stable baseline fEPSPs, LTP was induced by delivering 4 trains (each 1-s in duration) of 100 Hz separated by 30-s each.

Statistical analysis

The statistical tests performed were two-tailed Student’s t-test or Two-way ANOVA as indicated in the figure legend. In the case of a two-way ANOVA, post hoc analysis was done with Tukey’s test. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Sample sizes were determined to ensure confidence in the results. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes, but our sample sizes were similar to those reported in previous publications in the field15–17,41,42. For all experiments, there was enough statistical power to detect the corresponding effect size. Data distribution was assumed to be normal, and in some cases, normality of the sample data was assessed graphically with QQ-plots. Apparent extreme values were excluded from analysis. These values were justified by the context: imaging artifacts, cell death, etc. All steps of the experiments were randomized to minimize the effects of confounding variables. This includes how mice were chosen for injections, order of cell culture treatments, etc. Electrophysiology experiments were done blind. Imaging was done in similar fashions among conditions: fields from brain sections were chosen randomly from the region of interest, and images of cell cultures were taken randomly from all areas of the culture.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Sanes for critical comments on the manuscript; H. Enomoto for pSV loxp sv40 intron polyA EGFP FRTneo plasmid; A. Murayama and L. Kee for plasmid construction; E. Gibbs for help with in situ hybridization; D. Sorenson for help with electron microscopy; M. Zhang, R. Carson, and A. Williams for technical assistance; E. Hughes, Y. Qu, K. Childs, G. Gavrilina, D. Vanheyningen and the Transgenic Animal Model Core of the University of Michigan for preparation of SIRPα knockout mice. Core support was provided by the University of Michigan Center for Organogenesis. This work was supported by the Ester A. & Joseph Klingenstein Fund, the Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. Foundation, the March of Dimes Foundation, the Whitehall Foundation, and NIH grants MH091429, NS070005, and MH092614 (H.U.).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Neuroscience website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.U. designed experiments and prepared the manuscript. A.B.T., A.T., L.Y.Z., E.M.J.V., and D.J.L. performed experiments. M.A.S. and H.U. supervised the project. All authors analyzed data and commented on the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Lipska BK, Halim ND, Segal PN, Weinberger DR. Effects of reversible inactivation of the neonatal ventral hippocampus on behavior in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2835–2842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02835.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfeiffer BE, et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein is required for synapse elimination by the activity-dependent transcription factor MEF2. Neuron. 2010;66:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasai H, Fukuda M, Watanabe S, Hayashi-Takagi A, Noguchi J. Structural dynamics of dendritic spines in memory and cognition. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanes JR, Lichtman JW. Development of the vertebrate neuromuscular junction. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:389–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waites CL, Craig AM, Garner CC. Mechanisms of vertebrate synaptogenesis. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:251–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox MA, Umemori H. Seeking long-term relationship: axon and target communicate to organize presynaptic differentiation. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1215–1231. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalva MB, McClelland AC, Kayser MS. Cell adhesion molecules: signaling functions at the synapse. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:206–220. doi: 10.1038/nrn2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goda Y, Davis GW. Mechanisms of synapse assembly and disassembly. Neuron. 2003;40:243–264. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00608-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tessier CR, Broadie K. Activity-dependent modulation of neural circuit synaptic connectivity. Front Mol Neurosci. 2009;2:8. doi: 10.3389/neuro.02.008.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kano M, Hashimoto K. Synapse elimination in the central nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang LI, Poo M. Electrical activity and development of neural circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1207–1214. doi: 10.1038/nn753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bleckert A, Wong RO. Identifying roles for neurotransmission in circuit assembly: insights gained from multiple model systems and experimental approaches. Bioessays. 2011;33:61–72. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay L, Humphreys L, Eickholt BJ, Burrone J. Neuronal activity drives matching of pre- and postsynaptic function during synapse maturation. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:688–690. doi: 10.1038/nn.2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flavell SW, Greenberg ME. Signaling mechanisms linking neuronal activity to gene expression and plasticity of the nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:563–590. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umemori H, Linhoff MW, Onitz DM, Sanes JR. FGF22 and its close relatives are presynaptic organizing molecules in the mammalian brain. Cell. 2004;118:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umemori H, Sanes JR. Signal regulatory proteins (SIRPs) are secreted presynaptic organizing molecules. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34053–34061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805729200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terauchi A, Johnson-Venkatesh EM, Toth AB, Javed D, Sutton MA, Umemori H. Distinct FGFs promote differentiation of excitatory and inhibitory synapses. Nature. 2010;465:783–787. doi: 10.1038/nature09041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Beek EM, Cochrane F, Barclay AN, van den Berg TK. Signal regulatory proteins in the immune system. J Immunol. 2005;175:7781–7787. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.7781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barclay AN, Brown MH. The SIRP family of receptors and immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:457–464. doi: 10.1038/nri1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matozaki T, Murata Y, Okazawa H, Ohnishi H. Functions and molecular mechanisms of the CD47-SIRPα signaling pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danglot L, Triller A, Marty S. The development of hippocampal interneurons in rodents. Hippocampus. 2006;16:1032–1060. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steward O, Falk PM. Selective localization of polyribosomes beneath developing synapses: a quantitative analysis of the relationships between polyribosomes and developing synapses in the hippocampus and dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 1991;314:545–557. doi: 10.1002/cne.903140311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouvier D, Corera AT, Tremblay ME, Riad M, Chagnon M, Murai KK, Pasquale EB, Fon EA, Doucet G. Pre-synaptic and post-synaptic localization of EphA4 and EphB2 in adult mouse forebrain. J Neurochem. 2008;106:682–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biederer T, Scheiffele P. Mixed-culture assays for analyzing neuronal synapse formation. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:670–676. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo C, Yang W, Lobe CG. A Cre recombinase transgene with mosaic, widespread tamoxifen-inducible action. Genesis. 2002;32:8–18. doi: 10.1002/gene.10021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yasuda M, Johnson-Venkatesh EM, Zhang H, Parent JM, Sutton MA, Umemori H. Multiple forms of activity-dependent competition refine hippocampal circuits in vivo. Neuron. 2011;70:1128–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wayman GA, Lee YS, Tokumitsu H, Silva AJ, Soderling TR. Calmodulin-kinases: modulators of neuronal development and plasticity. Neuron. 2008;59:914–931. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ethell IM, Ethell DW. Matrix metalloproteinases in brain development and remodeling: synaptic functions and targets. J Neurosci Res. 2007:2813–2823. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindberg FP, Bullard DC, Caver TE, Gresham HD, Beaudet AL, Brown EJ. Decreased resistance to bacterial infection and granulocyte defects in IAP-deficient mice. Science. 1996;274:795–798. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang HP, Lindberg FP, Wang HL, Huang AM, Lee EH. Impaired memory retention and decreased long-term potentiation in integrin-associated protein-deficient mice. Learn Mem. 1999:448–457. doi: 10.1101/lm.6.5.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen K, Cowan CW. Guidance molecules in synapse formation and plasticity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(4):a001842. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams ME, de Wit J, Ghosh A. Molecular mechanisms of synaptic specificity in developing neural circuits. Neuron. 2010;68:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siddiqui TJ, Craig AM. Synaptic organizing complexes. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang XX, Pfenninger KH. Functional analysis of SIRPα in the growth cone. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:172–183. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohnishi H, et al. Stress-evoked tyrosine phosphorylation of signal regulatory protein α regulates behavioral immobility in the forced swim test. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10472–10483. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0257-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hatherley D, et al. Paired receptor specificity explained by structures of signal regulatory proteins alone and complexed with CD47. Mol Cell. 2008;31:266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatherley D, Graham SC, Harlos K, Stuart DI, Barclay AN. Structure of signal-regulatory protein α: a link to antigen receptor evolution. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26613–26619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.017566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards DR, Handsley MM, Pennington CJ. The ADAM metalloproteinases. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:258–289. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reiss K, Saftig P. The “a disintegrin and metalloprotease” (ADAM) family of sheddases: physiological and cellular functions. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bai G, Pfaff SL. Protease Regulation: The Yin and Yang of Neural Development and Disease. Neuron. 2011;72:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peixoto RT, et al. Transsynaptic signaling by activity-dependent cleavage of neuroligin-1. Neuron. 2012;76:396–409. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki K, et al. Activity-dependent proteolytic cleavage of neuroligin-1. Neuron. 2012;76:410–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaeren-Wiemers N, Gerfin-Moser A. A single protocol to detect transcripts of various types and expression levels in neural tissue and cultured cells: in situ hybridization using digoxigenin-labelled cRNA probes. Histochemistry. 1993;100:431–440. doi: 10.1007/BF00267823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uesaka T, et al. Conditional ablation of GFRα1 in postmigratory enteric neurons triggers unconventional neuronal death in the colon and causes a Hirschsprung’s disease phenotype. Development. 2007;134:2171–2181. doi: 10.1242/dev.001388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woodhams PL, Webb M, Atkinson DJ, Seeley PJ. A monoclonal antibody, Py, distinguishes different classes of hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1989;9:2170–2181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-06-02170.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oldenborg PA, Zheleznyak A, Fang YF, Lagenaur CF, Gresham HD, Lindberg FP. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science. 2000;288:2051–4. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohnishi H, et al. Ectodomain shedding of SHPS-1 and its role in regulation of cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27878–27887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hahn CG, et al. The post-synaptic density of human postmortem brain tissues: an experimental study paradigm for neuropsychiatric illnesses. PLoS One. 2009;4(4):e5251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.