Abstract

Background

The estimated prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) is 8 for every 1000 live births. FAS has serious, lifelong consequences for the affected children and their families. A variety of professionals deal with persons who have FAS, including pediatricians, general practitioners, neurologists, gynecologists, psychiatrists, and psychotherapists. Early diagnosis is important so that the affected children can receive the support they need in a protective environment.

Methods

A multidisciplinary guideline group has issued recommendations for the diagnosis of FAS after assessment of the available scientific evidence. This information was derived from pertinent literature (2001–2011) retrieved by a systematic search in PubMed and the Cochrane Library, along with the US-American and Canadian guidelines and additional literature retrieved by a manual search.

Results

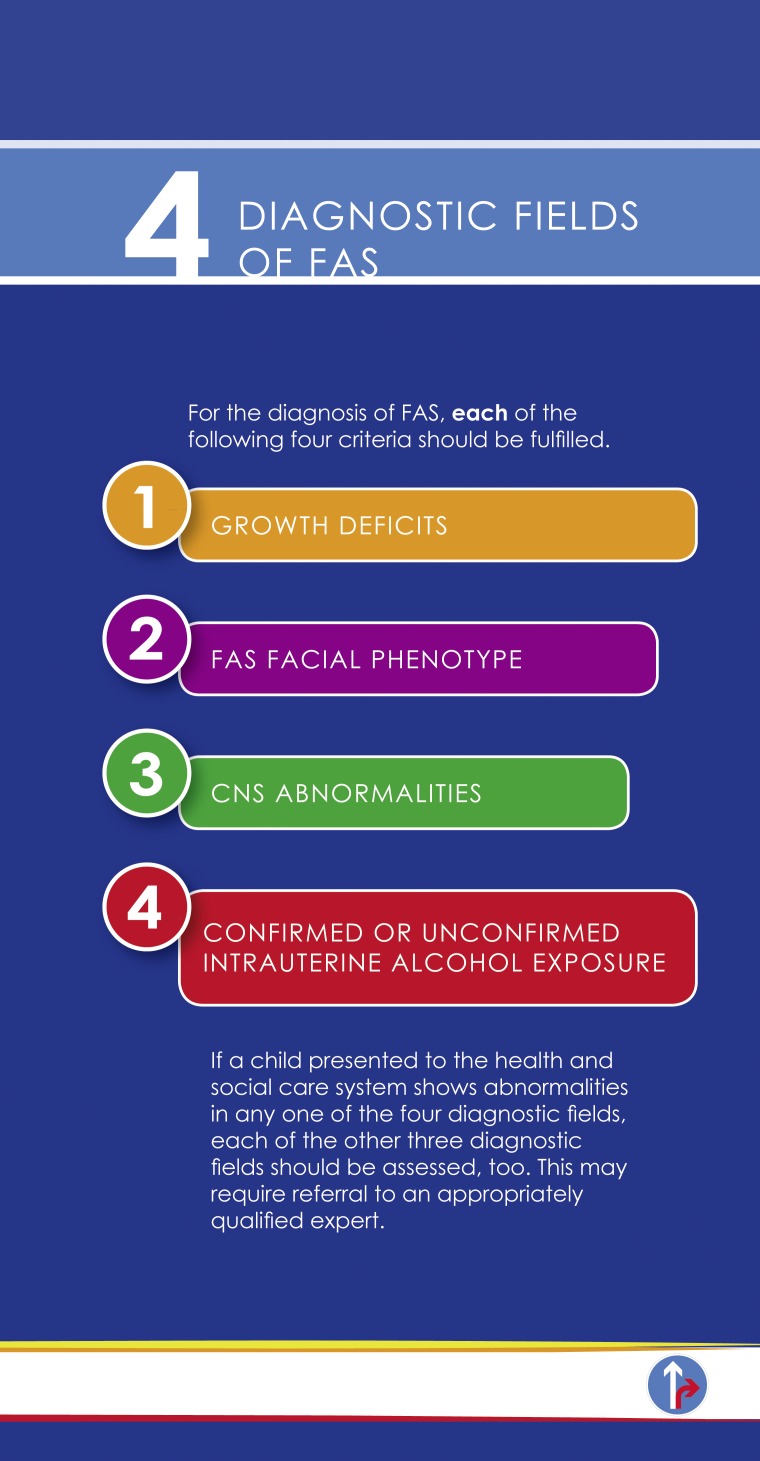

Of the 1383 publications retrieved by the searches, 178 were analyzed for the evidence they contained. It was concluded that the fully-developed clinical syndrome of FAS should be diagnosed on the basis of the following criteria: Patients must have at least one growth abnormality, e.g., short stature, as well as all three characteristic facial abnormalities—short palpebral fissure length, a thin upper lip, and a smooth philtrum. They must also have at least one diagnosed structural or functional abnormality of the central nervous system, e.g., microcephaly or impaired executive function. Confirmation of intrauterine exposure to alcohol is not obligatory for the diagnosis.

Conclusion

Practical, evidence-based criteria have now been established for the diagnosis of the fully-developed FAS syndrome. More research is needed in order to enable uniform, evidence-based diagnostic assessment of all fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and optimize supportive measures for the children affected by them.

The deleterious effects of intrauterine exposure to alcohol are collectively referred to as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). The spectrum includes:

Full-blown fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS)

Partial fetal alcohol syndrome (pFAS)

Alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND)

Alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD).

Reports of the prevalence of FAS vary considerably due to the methodological weaknesses of some studies and the heterogeneity of both the samples and the diagnostic criteria. Two population-based cross-sectional studies in Italy estimate prevalence of 7.4 and 8.2 per 1000 live births (1, 2). The number of pregnant women who drink alcohol is much higher than the number who give birth to a child with FAS (3). There is no simple dose–effect relationship, so on the basis of our current knowledge no safe threshold level of alcohol consumption for pregnant women can be defined. Equally, it cannot be stated what proportion of women who consume what quantity of alcohol will have a child with FASD. The studies to date have paid insufficient systematic attention to parameters such as age, ethnicity, nutrition, other pre- and perinatal complications, and genetic factors. Information provided by the mothers is unreliable, and there are no valid means of measuring intrauterine exposure to alcohol throughout the whole pregnancy. The only certain way of avoiding FAS is to abstain from alcohol completely.

The brain injury caused by intrauterine exposure to alcohol is irreversible. The children concerned have functional impairments and problems coping with daily life. They are more likely to drop out of school, and show higher rates of alcohol and drug abuse, abnormal sexual behavior, and delinquency (4). Prompt, adequate diagnosis of FAS is necessary for early support measures, including creation of a protective environment, and can help to avoid problems in future years. A case series showed that diagnosis after the age of 12 years together with absence of a protective environment was associated with considerably increased rates of the above-mentioned problems (odds ratio [OR] 2.25 to 4.16) (4). We know of no randomized controlled studies of the options for treatment and secondary prevention. Research into specific interventions is required. It is plausible, however, that targeted support measures may be beneficial in children with FAS, as has been shown for children with other neurological disorders. Communication of the diagnosis of FAS avoids false conclusions about the cause of the disorder and relieves the pressure on the affected family.

Methods

The guideline project was initiated by the German federal government’s commissioner on drug-related issues and conducted by the Society of Neuropediatrics (Gesellschaft für Neuropädiatrie), supported by the Agency for Quality in Medicine (ÄZQ) and the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF). The participating professional associations, patient representatives, and experts are listed in eTable 1. The key question was agreed to be: What criteria enable development-based diagnosis of full-blown fetal alcohol syndrome in children and adolescents (age range 0 to 18 years)?

eTable 1. Composition of guideline consensus group.

| Participating professional societies | Representative |

| German Society for Child and Adolescent Medicine | Prof. Dr. med. Florian Heinen |

| Society for Neuropediatrics | Prof. Dr. med. Florian Heinen |

| German Society for Social Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine | Dr. med. Juliane Spiegler |

| German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics | Prof. Dr. med. Franz Kainer |

| Society for Neonatology and Pediatric Intensive Care | Prof. Dr. med. Rolf F. Maier |

| German Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy | Prof. Dr. med. Frank Häßler |

| German Society for Addiction Research and Addiction Therapy | Dr. med. Regina Rasenack |

| German Society of Addiction Psychology | Prof. Dr. Dipl.-Psych. Tanja Hoff |

| German Society for Addiction Medicine | PD Dr. med. Gerhard Reymann |

| German Society of Midwifery Science | Prof. Dr. rer. medic. Rainhild Schäfers |

| German Association of Midwives | Regine Gresens |

| The Association of German Professional Psychologists | Dipl.-Psych. Laszlo A. Pota |

| German Professional Association of Pediatricians | Dr. Dr. med. Nikolaus Weissenrieder |

| German Federal Association of Public Health Physicians | Dr. med. Gabriele Trost-Brinkhues |

| Function | Expert |

| Director, Protestant Children’s Home "Sonnenhof" | Dipl.-Psych. Gela Becker |

| Bavarian Academy for Addiction and Health Issues | Dr. med. Beate Erbas |

| FASD Center, University of Münster | Dr. Dipl.-Psych. Reinhold Feldmann |

| Department of Neonatology and Neuropediatrics, University of Munich (LMU) | PD Dr. med. Anne Hilgendorff |

| Medical Director, KMG Rehabilitation Center, Sülzhayn | Dr. med. Heike Hoff-Emden |

| Board member of the DGSPJ, Public Health Authority, Recklinghausen | Dr. med. Ulrike Horacek |

| Department of Neuropediatrics, FASD Clinic, Integrated Social Pediatric Center Munich (iSPZ), University of Munich (LMU) | Dr. med. Dipl.-Psych. Mirjam Landgraf |

| Chair, Patientenvertretung FASD Deutschland e. V. (an organization representing the interests of FASD patients in Germany) | Gisela Michalowski |

| Board member, Patientenvertretung FASD Deutschland e. V. | Veerle Moubax |

| Municipal Youth Welfare Office, Munich | Carla Pertl |

| Office for Child and Adolescent Health Protection, Department for Health and the Environment of the State Capital Munich | Dr. med. Monika Reincke |

| Department of Neonatology, University of Munich (LMU) | Andreas Rösslein |

| Attorney specializing in child and youth welfare law | Gila Schindler |

| Director, Department of Neonatology, University of Munich (LMU) | Prof. Dr. med. Andreas Schulze |

| Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, FASD Clinic, Heckscher Hospital, Munich | Dr. med. Martin Sobanski |

| FASD Center, Charité Berlin | Prof. Dr. med. Hans-Ludwig Spohr |

| Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, FASD Clinic, Heckscher Hospital, Munich | Dipl.-Psych. Penelope Thomas |

| FASD Center, Charité Berlin | Dipl.-Psych. Jessica Wagner |

| Board member, Patientenvertretung FASD Deutschland e. V. | Dr. med. Wendelina Wendenburg |

| Institute for Medical Information Processing, Biometrics, and Epidemiology, University of Munich (LMU) | Dr. Eva Rehfueß (nonvoting member) |

| Consultant on study methods, moderation: AWMF Institute for Management of Medical Knowledge | Prof. Dr. med. Ina Kopp (nonvoting member) |

| Consultant on study methods, evidence report: Director, Division of Knowledge Management, Agency for Quality in Medicine (ÄZQ) | Dr. med. Monika Nothacker MPH (nonvoting member) |

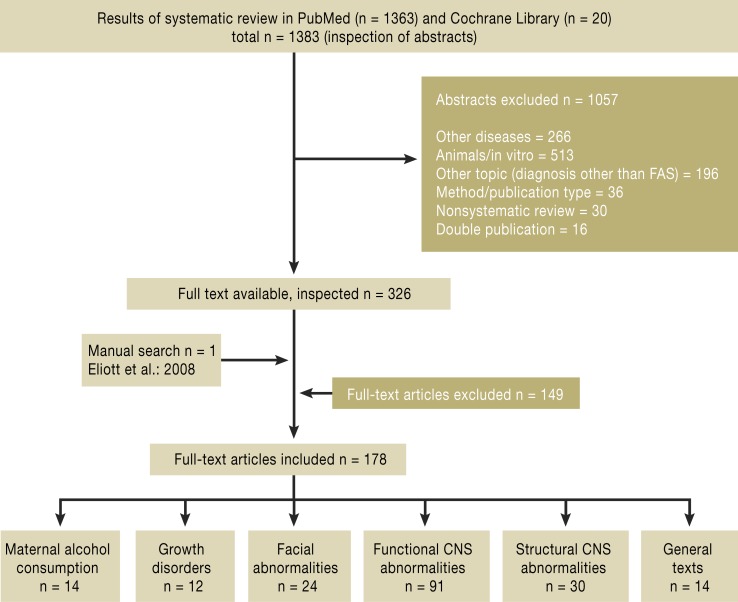

A systematic literature review and evaluation of the evidence was carried out by the ÄZQ (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Design and results of the systematic literature review (search period 1 January 2001 to 31 October 2011; see eTable 3 for exclusion criteria). FAS, fetal alcohol syndrome

The literature search embraced all English- and German-language articles in Medline (PubMed) and the Cochrane Library published between 1 January 2001 and 31 October 2011 (for description of the search strategy and the prospectively defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, see eTable 2 and eTable 3), with a manual search for the period before 2001.

eTable 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for abstracts and full-text articles in the systematic literature review.

| Inclusion criteria for abstracts and full text | |

| Population | Children and adolescents (<18 years) with fetal alcohol syndrome (fas) |

| Intervention | Diagnostic tests for the following criteria:

|

| Controls | Healthy children and adolescents Children and adolescents with a diagnosed neuropsychological disorder other than FAS (e.g., ADHD) Children and adolescents with partial FAS, alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorders, and alcohol-related birth defects |

| End points | The principal end point was the diagnostic discrimination of the test procedures in relation to FAS; no other study parameters were defined |

| Study types | Inclusion of randomized controlled trials, secondary inclusion of cohort or case–control studies, case reports, case series (>10 patients), systematic reviews, and meta-analyses of these studies. Note: case series were excluded at the second, full-text inspection |

| Languages | English, German |

| Exclusion criteria for abstracts and full text | |

| E1 | Other disease |

| E2 | Studies on animals or in vitro |

| E3 | Other topic (not diagnosis of or screening for FAS) |

| E4 | Method of publication, other type of publication |

| E5 | Nonsystematic review |

| E6 | Probands predominantly (more than 80%) >18 years old |

| E7 | Regarding maternal alcohol consumption: publications before 2008 were excluded because of the existence of a systematic review by Elliot et al. (3) covering the literature up to July 2008 |

| E8 | Double publications (duplicates) |

eTable 3. Search strategy in PubMed and the Cochrane Library.

| Search strategy in PubMed (internet portal of the National Library of Medicine) (www.pubmed.org) on 31 October 2011 | ||

| No. | Search term | Number |

| #6 | #1 AND #4 Limits: English, German, publication date from 2001 | 1363 |

| #5 | #1 AND #4 | 3480 |

| #4 | #2 OR #3 | 7 693 746 |

| #3 | (developmental AND (defect OR defects OR abnormality OR abnormalities OR anomaly OR anomalies)) OR deficits OR growth deficiency OR facial phenotype OR („central nervous system“ AND (damage OR dysfunction)) OR ((cognitive OR communication OR behavioral) AND (difficulties OR disabilities)) OR adverse life outcomes OR mental health concerns OR ((fluency OR articulation) AND abilities) (Details: (developmental[All Fields] AND (defect[All Fields] OR („abnormalities“[Subheading] OR „abnormalities“[All Fields] OR „defects“[All Fields]) OR abnormality[All Fields] OR („abnormalities“[Subheading] OR „abnormalities“[All Fields] OR „congenital abnormalities“[MeSH Terms] OR („congenital“[All Fields] AND „abnormalities“[All Fields]) OR „congenital abnormalities“[All Fields]) OR anomaly[All Fields] OR („abnormalities“[Subheading] OR „abnormalities“[All Fields] OR „anomalies“[All Fields]))) OR deficits[All Fields] OR ((„growth and development“[Subheading] OR („growth“[All Fields] AND „development“[All Fields]) OR „growth | 234 689 |

| #2 | diagnostic OR diagnosis OR diagnoses OR screening („diagnosis“[MeSH Terms] OR „diagnosis“[All Fields] OR „diagnostic“[All Fields]) OR („diagnosis“[Subheading] OR „diagnosis“[All Fields] OR „diagnosis“[MeSH Terms]) OR („diagnosis“[MeSH Terms] OR „diagnosis“[All Fields] OR „diagnoses“[All Fields]) OR („diagnosis“[Subheading] OR „diagnosis“[All Fields] OR „screening“[All Fields] OR „mass ‧screening“[MeSH Terms] OR („mass“[All Fields] AND „screening“[All Fields]) OR „mass screening“[All Fields] OR „screening“[All Fields]) | 7 587 987 |

| #1 | fetal alcohol syndrome OR fetal alcohol related deficit OR fetal alcohol spectrum disorders OR FASD OR (alcohol AND embryopathy) OR fetal alcohol effects (Details: („foetal alcohol syndrome“[All Fields] OR „fetal alcohol syndrome“[MeSH Terms] OR („fetal“[All Fields] AND „alcohol“[All Fields] AND „syndrome“[All Fields]) OR „fetal alcohol syndrome“[All Fields]) OR ((„fetus“[MeSH Terms] OR „fetus“[All Fields] OR „fetal“[All Fields]) AND („ethanol“[MeSH Terms] OR „ethanol“[All Fields] OR „alcohol“[All Fields] OR „alcohols“[MeSH Terms] OR ‧„alcohols“[All Fields]) AND related[All Fields] AND („malnutrition“[MeSH Terms] OR „malnutrition“[All Fields] OR „deficit“[All Fields])) OR ((„fetus“[MeSH Terms] OR „fetus“[All Fields] OR „fetal“[All Fields]) AND („ethanol“[MeSH Terms] OR „ethanol“[All Fields] OR „alcohol“[All Fields] OR „alcohols“[MeSH Terms] OR „alcohols“[All Fields]) AND („Spectrum“[Journal] OR „spectrum“[All Fields]) AND („disease“[MeSH Terms] OR „disease“[All Fields] OR „disorders“[All Fields])) OR FASD[All | 5953 |

| Search strategy in the Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com) on 31 October 2011 | ||

| No. | Search term | Number |

| #3 | #1 AND #2 from 2001 to 2011 | 20 |

| #2 | (developmental AND (defect OR defects OR abnormality OR abnormalities OR anomaly OR anomalies)) OR deficits OR growth deficiency OR facial phenotype OR („central nervous system“ AND (damage OR dysfunction)) OR ((cognitive OR communication OR behavioral) AND (difficulties OR disabilities)) OR adverse life outcomes OR mental health concerns OR ((fluency OR articulation) AND abilities) in Title, Abstract or Keywords or diagnostic OR diagnosis OR diagnoses OR screening in Title, Abstract or Keywords | 85 863 |

| #1 | fetal alcohol syndrome OR fetal alcohol related deficit OR fetal alcohol spectrum disorders OR FASD OR (alcohol AND embryopathy) OR fetal alcohol effects in title, abstract or keywords | 46 |

| = | Total number of hits Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3) Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (1) Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (14) Cochrane Methodology Register (0) Health Technology Assessment Database (1) NHS Economic Evaluation Database (1) |

20 3 1 14 0 1 1 |

The selected full-text articles were systemically assessed with regard to the quality of their methods. The strength of evidence was determined according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine’s classification for diagnostic studies (2009 version; www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1025) (eTable 4).

eTable 4. Level of evidence (LoE) according to the criteria of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine (www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1025).

| Evidence level | Study design |

|---|---|

| 1a | Systematic review of level 1 diagnostic studies;or clinical decision rule with 1b studies from different clinical centres |

| 1b | Validating cohort study with good reference standard; or clinical decision rule tested within one clinical centre |

| 1c | Absolute SpPins und SnNouts* |

| 2a | Systematic review of well-planned cohort studies |

| 2b | A well-planned cohort study or a lesser-quality randomized controlled study |

| 2c | Outcome studies, "ecological studies" = registry studies |

| 3a | Systematic review of 3b and better studies |

| 3b | Nonconsecutive study; or without consistently applied reference standards |

| 4 | Case–control study, poor or nonindependent reference standard |

| 5 | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal of the evidence or based on physiological models/laboratory research |

*"Absolute SpPin", diagnostic finding whose Specificity is so high that a Positive result rules-in the diagnosis; „absolute SnNout“, diagnostic finding whose Sensitivity is so high that a Negative result rules-out the diagnosis

This classification distinguishes three grades of recommendation (A, B, and 0), whose strength is expressed as “we recommend,” “we suggest,” and “may be considered.” As a rule, the strength of recommendation is determined by the quality of the evidence. However, the following parameters were also taken into consideration:

Benefit versus risk

The clinical relevance of the study parameters and effect strengths

The external validity and consistency of the study results

Ethical considerations.

In the case of diagnostic criteria that were adjudged to be of extreme clinical relevance but for which no sufficient evidence could be found, a guideline recommendation was formulated on the basis of expert consensus. All recommendations were adopted in a formal agreement process (nominal group process with external moderation).

Results

The systematic review of PubMed and the Cochrane Library identified 1363 and 20 publications respectively. After inspection of the abstracts, 326 publications were selected for full-text assessment. According to prospectively established criteria 178 publications were included in the study (Figure 1). We know of no studies published in the period November 2011 to June 2013 whose findings would lead to modification of the diagnostic criteria.

The formal agreement process resulted in seven key recommendations (R 1 to R 7) (Table). Furthermore, clarifying recommendations on diagnosis were formulated.

Table. Key recommendations on diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS).

| Diagnostic recommendation | Evidence level | Grade of recommendation |

|---|---|---|

|

R 1: For FAS to be diagnosed, abnormalities should be present in all four diagnostic categories: 1. Growth abnormalities 2. Facial abnormalities 3. Abnormalities of the central nervous system (CNS) 4. Confirmed or unconfirmed intrauterine alcohol exposure. Whenever the health/support services are contacted, a child with abnormalities in any one of these categories should be investigated (or referred for investigation) of the other three diagnostic categories. |

Expert consensus | |

|

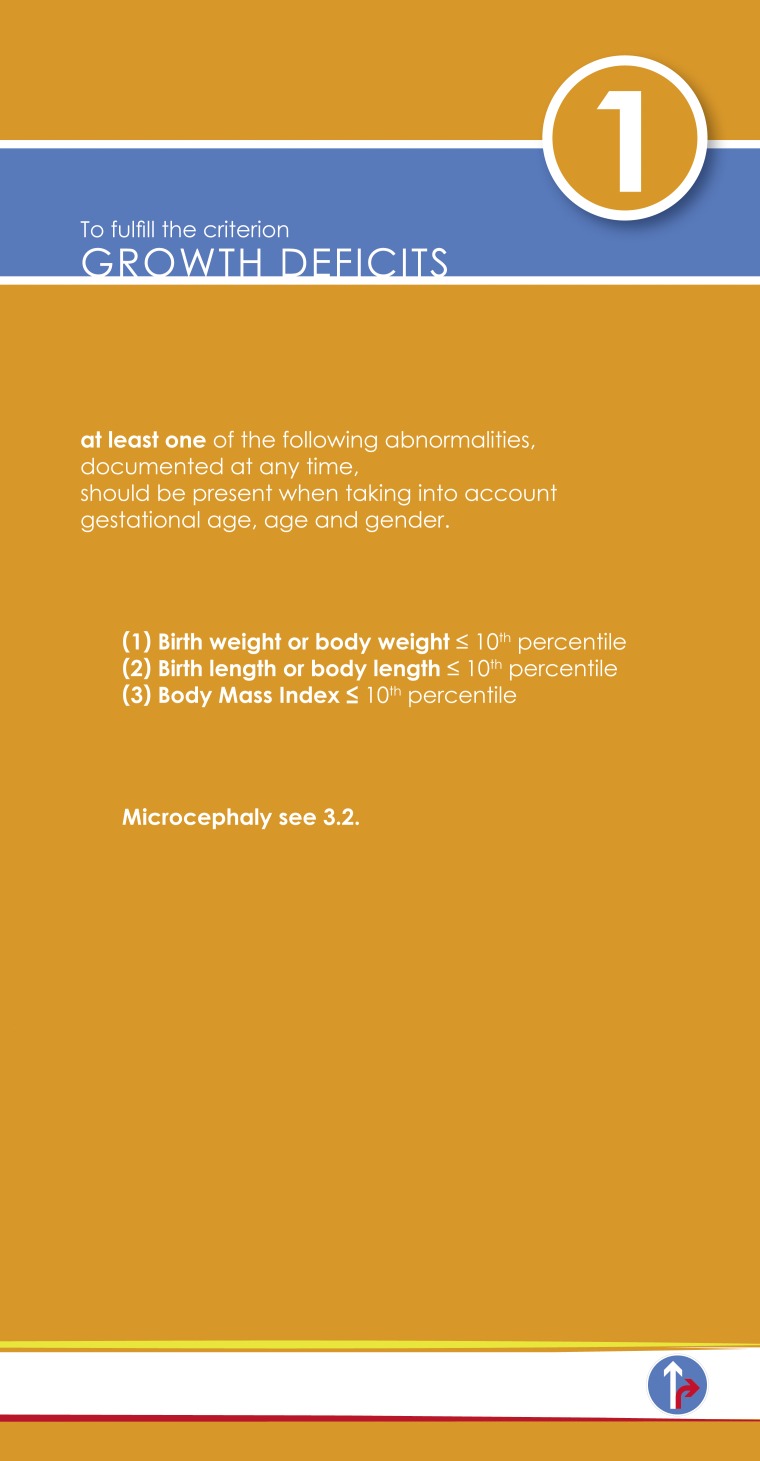

R 2: For fulfillment of the criterion "growth abnormalities," at least one of the following abnormalities, adapted to gestational age, age, and sex, should be documented at any given time: 1. Birth weight or body weight ≤ 10 th percentile 2. Birth length or body length ≤ 10 th percentile 3. Body mass index ≤ 10 th percentile |

2 | A: Strong consensus |

|

R 3: For fulfillment of the criterion "facial abnormalities," all three facial anomalies should be documented at any given time: 1. Short palpebral fissure length (≤ 3 rd percentile) 2. Smooth philtrum (lip-philtrum guide grade 4 or 5) 3. Thin upper lip (lip-philtrum guide grade 4 or 5) |

1 | A: Strong consensus |

|

R 4: For fulfillment of the criterion "abnormalities of the central nervous system (CNS)," at least one of the following should be documented: 1. Functional CNS abnormalities 2. Structural CNS abnormalities |

Expert consensus | |

|

R 5: For fulfillment of the criterion "functional CNS abnormalities," at least one of the following abnormalities, inappropriate for age and not solely explained by family background or social environment, should be documented:

|

2–4 | B: Consensus |

|

R 6: For fulfillment of the criterion "structural CNS abnormalities," the following abnormality, adapted to gestational age, age, and sex, should be documented at any given time: Microcephaly ≤ 10 th percentile / ≤ 3 rd percentile |

2 | B: Strong consensus |

|

R 7: If abnormalities are present in all three of the other diagnostic categories, FAS should be diagnosed even if consumption of alcohol by the mother during pregnancy is not confirmed. |

3 | A: Consensus |

All recommendations (exception: cut-off values for head-circumference percentile) were adopted with “strong agreement” (endorsed by more than 95% of the participants of the guideline consensus group) or with “agreement” (endorsed by more than 75% of the participants).

Clarifying recommendations on diagnostic procedures

R 1: Diagnostic categories

Multimodal and interdisciplinary assessment is recommended in any child suspected to have FAS (expert consensus).

R 2: Growth abnormalities

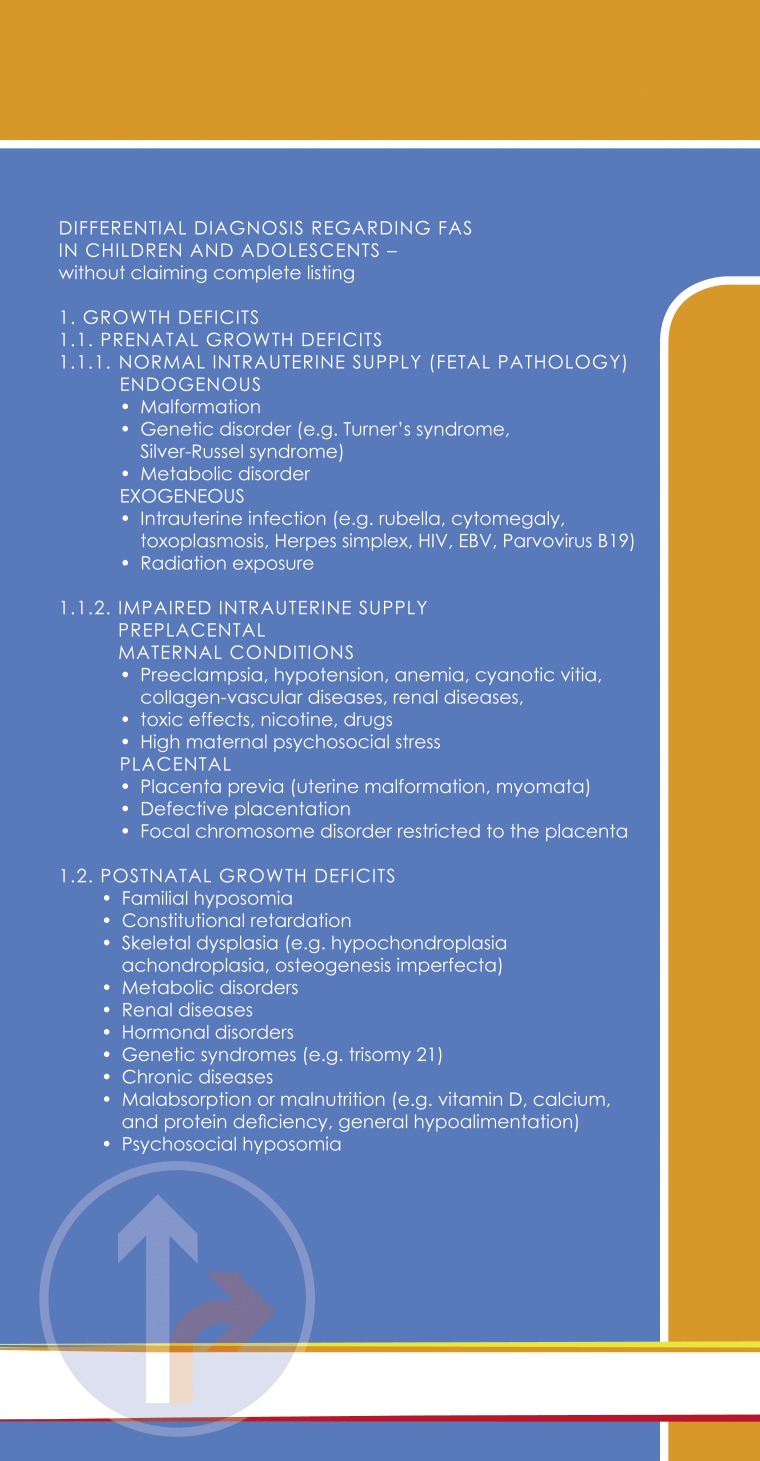

Klug et al. (5) retrospectively evaluated a consecutive cohort of 322 children who attended outpatient consultations. The percentiles for weight at birth and body weight at the time of examination were significantly lower in children with FAS (mean percentile 18.2/31.5) than in children without FAS (mean percentile 39.6/56.5; p<0.001). The percentiles for body length at birth and time of examination were also significantly lower in children with FAS (mean percentile 33.5/30.5 versus 58.6/51.1; p<0.001). Moreover, 22% of the children with FAS (26/120) had a body mass index below the 3rd percentile, compared with 3% of those without FAS (2/70) (level of evidence [LoE] 2b-). Day et al. (cohort study, n = 580) (6) found that 14-year-old children whose mothers had drunk alcohol in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy showed reduced body weight, and maternal alcohol consumption in the first trimester led to smaller body length (LoE 2b).

Explanation of the growth disturbance purely by other causes has to be excluded (expert consensus).

These potential causes include:

Familial microsomia

Constitutional developmental retardation

Prenatal deficiency states

Skeletal dysplasia

Hormonal disorders

Genetic syndromes

Chronic diseases

Malabsorption

Malnutrition

Neglect.

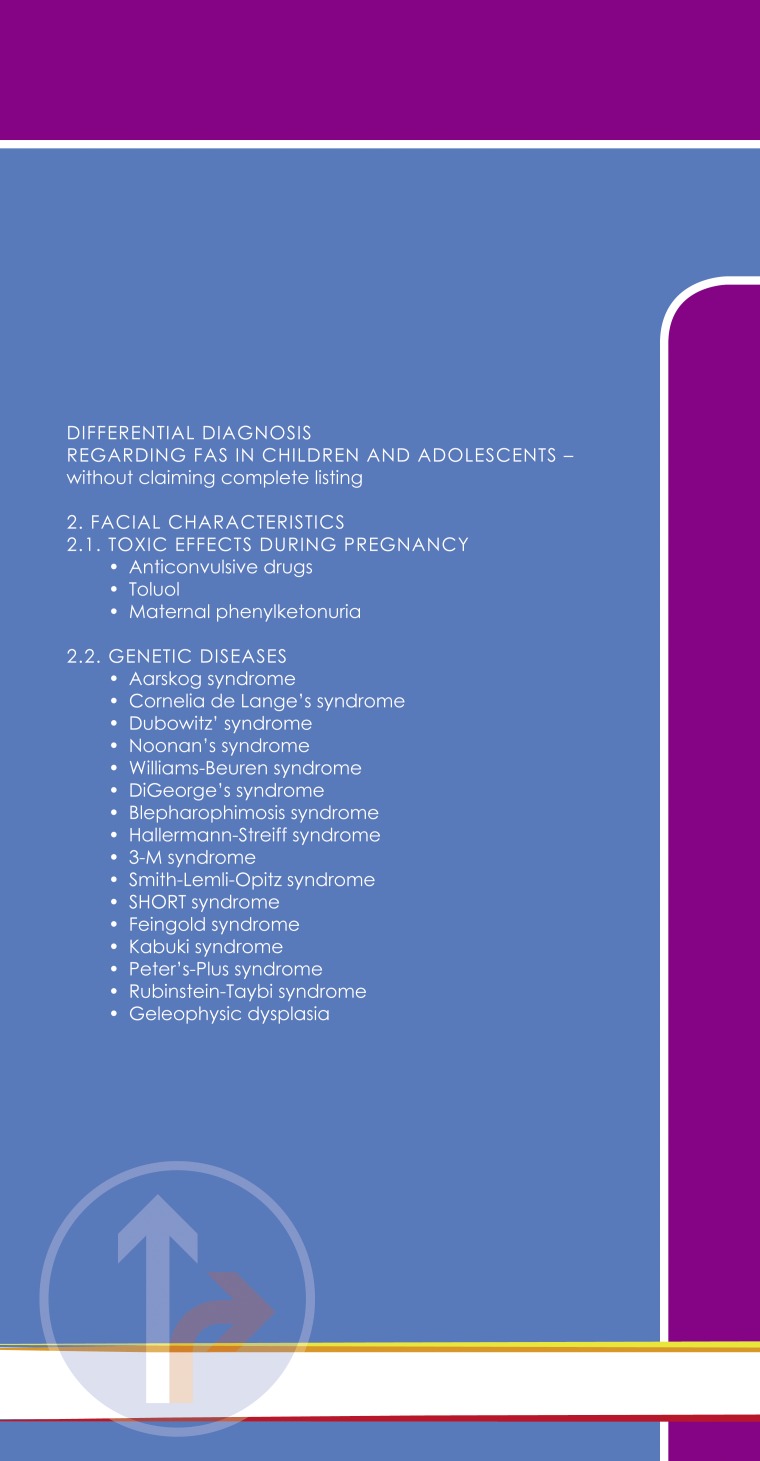

R 3: Facial anomalies

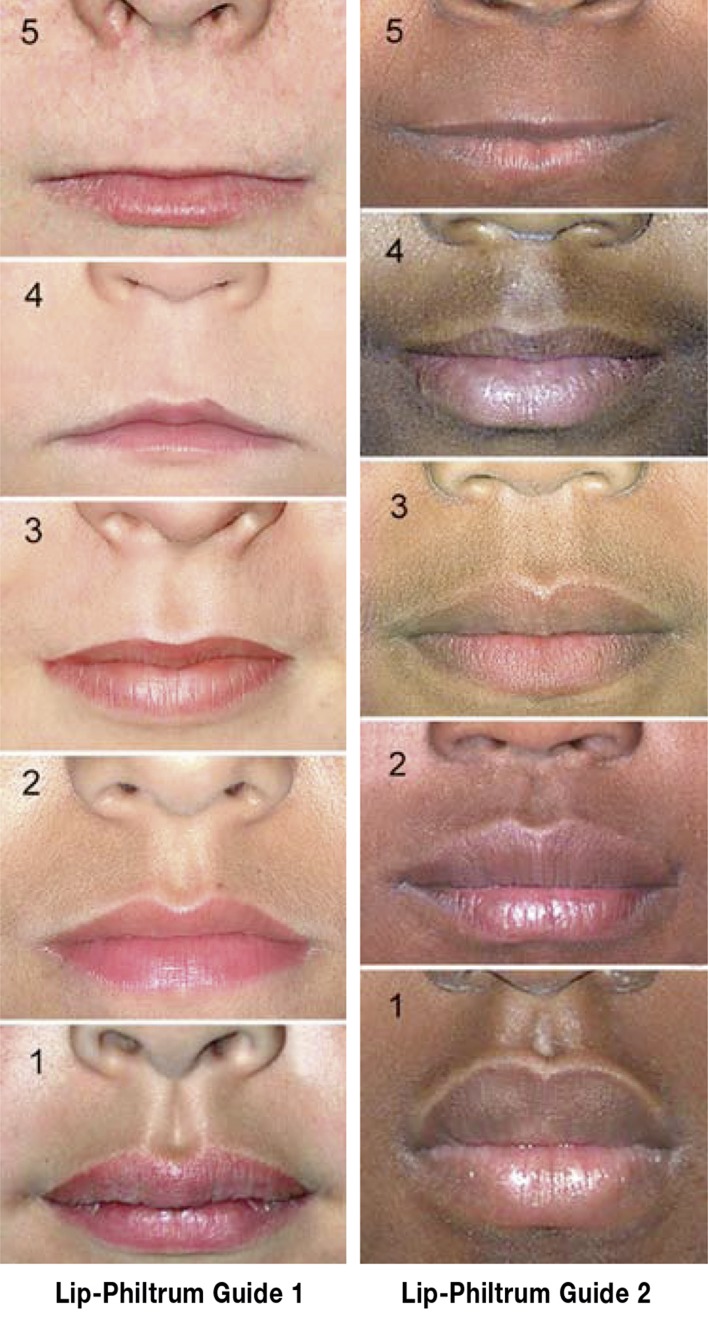

In 1976, Jones et al. (case series, n = 48) (7) described characteristic abnormalities of the facial features in children with intrauterine exposure to alcohol. This was confirmed in a case–control study (LoE 4) by Clarren et al. in 1987 (severe [n = 21] versus negligible [n = 21] exposure to alcohol) (8). On the basis of a validation cohort study (FAS n = 39, no FAS n = 155; LoE 1b-) published in 1995, Astley and Clarren described a combination of facial characteristics specific to FAS (9). Regardless of ethnicity and sex, the most powerful discriminating characteristics for FAS proved to be smoothing of the philtrum, a thin upper lip, and short palpebral fissure length. These facial screening criteria for FAS showed sensitivity of 100% and acceptable specificity of 89.4%.

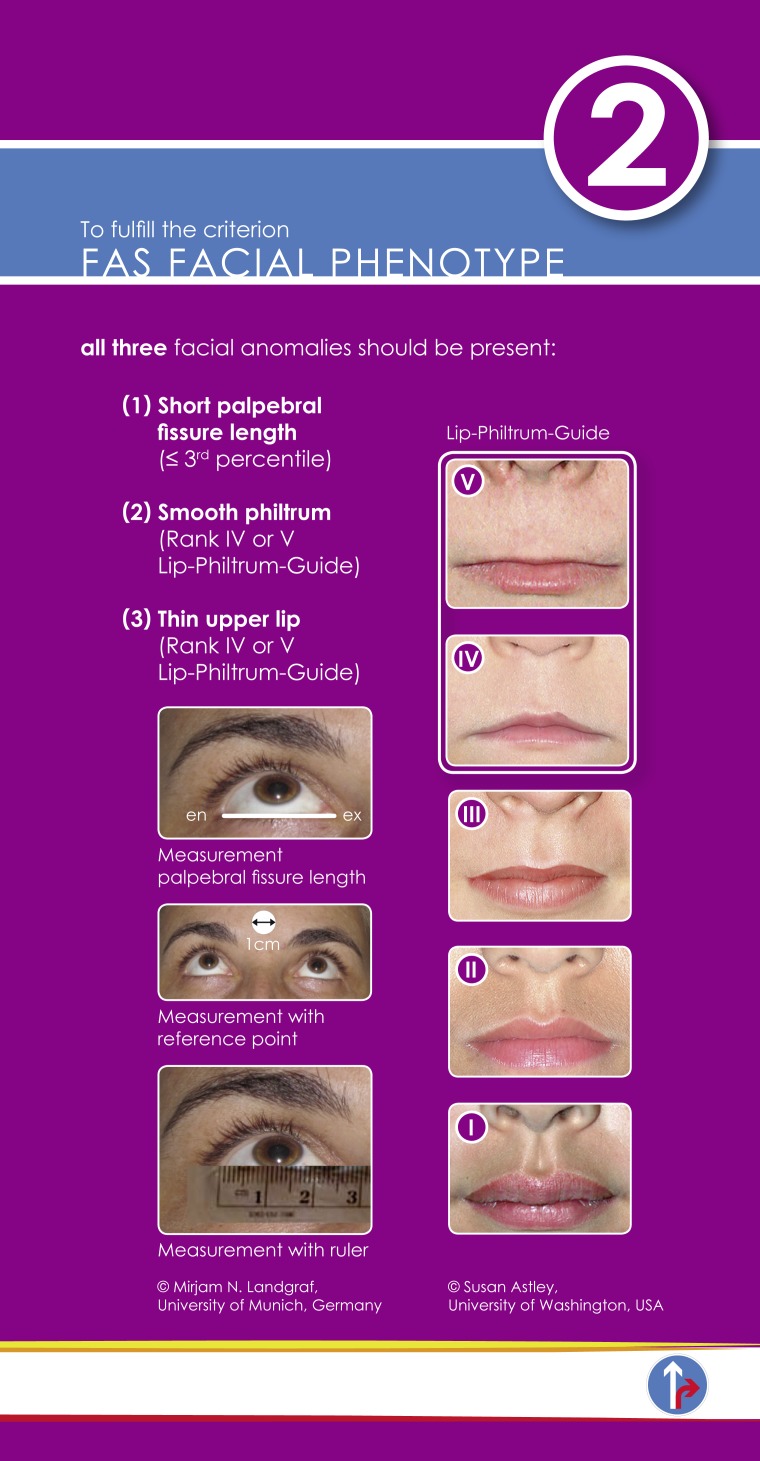

To aid quantitative assessment of upper lip thickness and philtrum smoothness, Astley and Clarren (10, 11) developed a lip–philtrum guide with five photographs comparable to a five-point Likert scale. Upper lip and philtrum scores of 4 or 5 on this scale are considered pathological in the context of suspected FAS (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lip–philtrum guide (left Caucasian, right African ethnicity) for assessment of thickness of the upper lip and smoothness of the philtrum (the vertical groove between nose and upper lip). Grade 3 = average appearance in the normal population. Grade 4 and 5 = thin upper lip and smooth philtrum characteristic of FAS (© 2013 Susan Astley PhD, University of Washington)

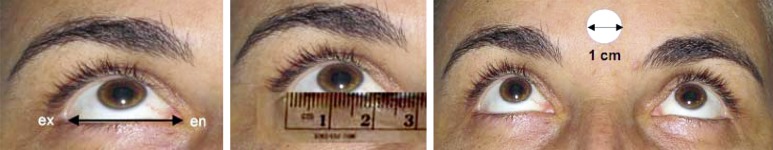

The length of the palpebral fissure can be measured using a transparent ruler, either directly or on a photograph furnished with a circle of diameter corresponding to 1 cm on the patient’s forehead for reference (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Measurement of palpebral fissure length from endocanthion (en) to exocanthion (ex) by means of a transparent ruler, either directly or on a photograph furnished with a circle of diameter corresponding to 1 cm for reference

In 2010, Clarren et al. (12) developed percentile curves for palpebral fissure length based on measurements in 2097 healthy Canadian girls and boys ranging in age from 6 to 16 years (explorative cohort study, LoE 2b). In a population from the USA, Astley et al. (13) showed that the mean palpebral fissure lengths of children with FAS (n = 22) were at least two standard deviations lower than the corresponding values in healthy Canadian children (statistical validation study, LoE 2b-), while those of healthy children (n = 90) were within the normal range. There are no recent data on percentile curves for palpebral fissure length in children under 6 years of age (14– 16).

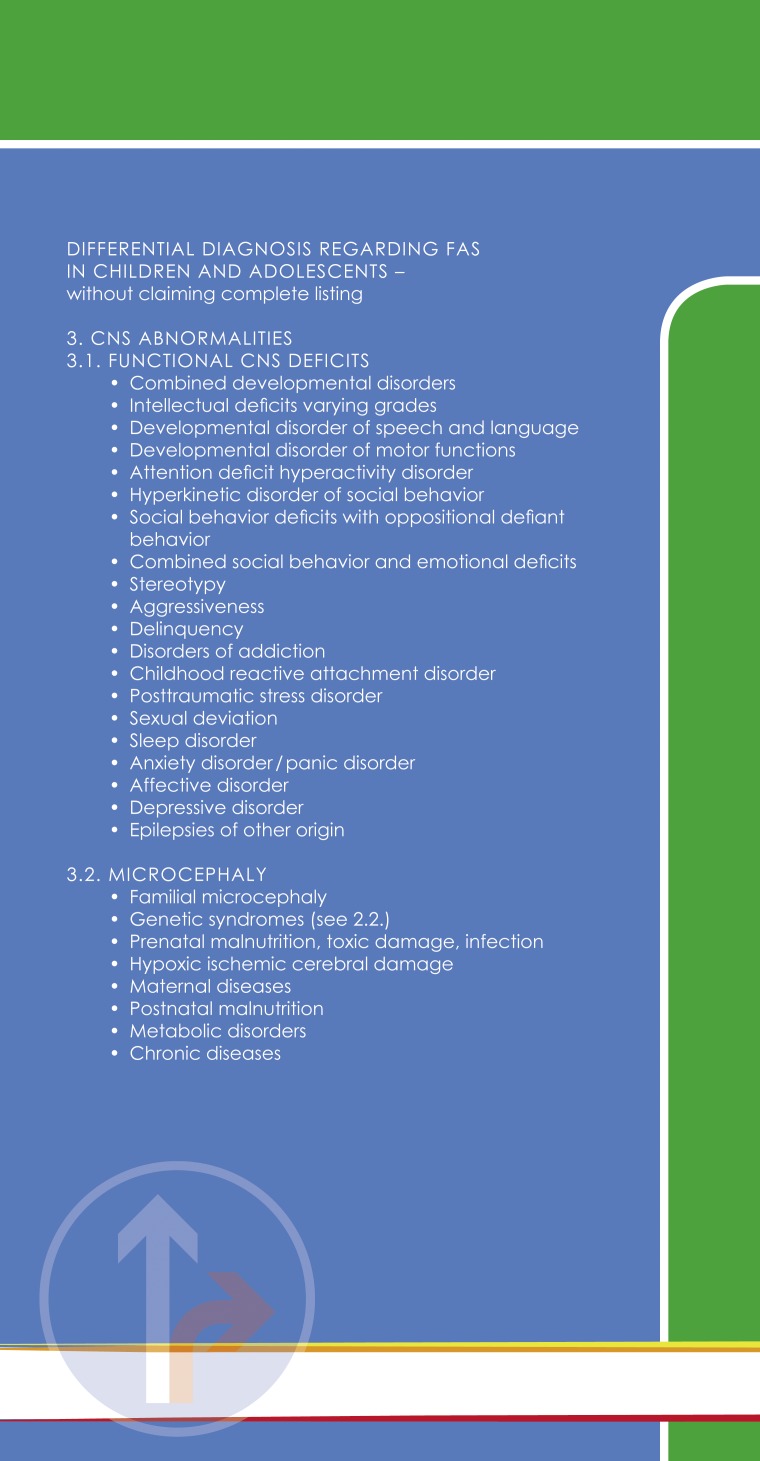

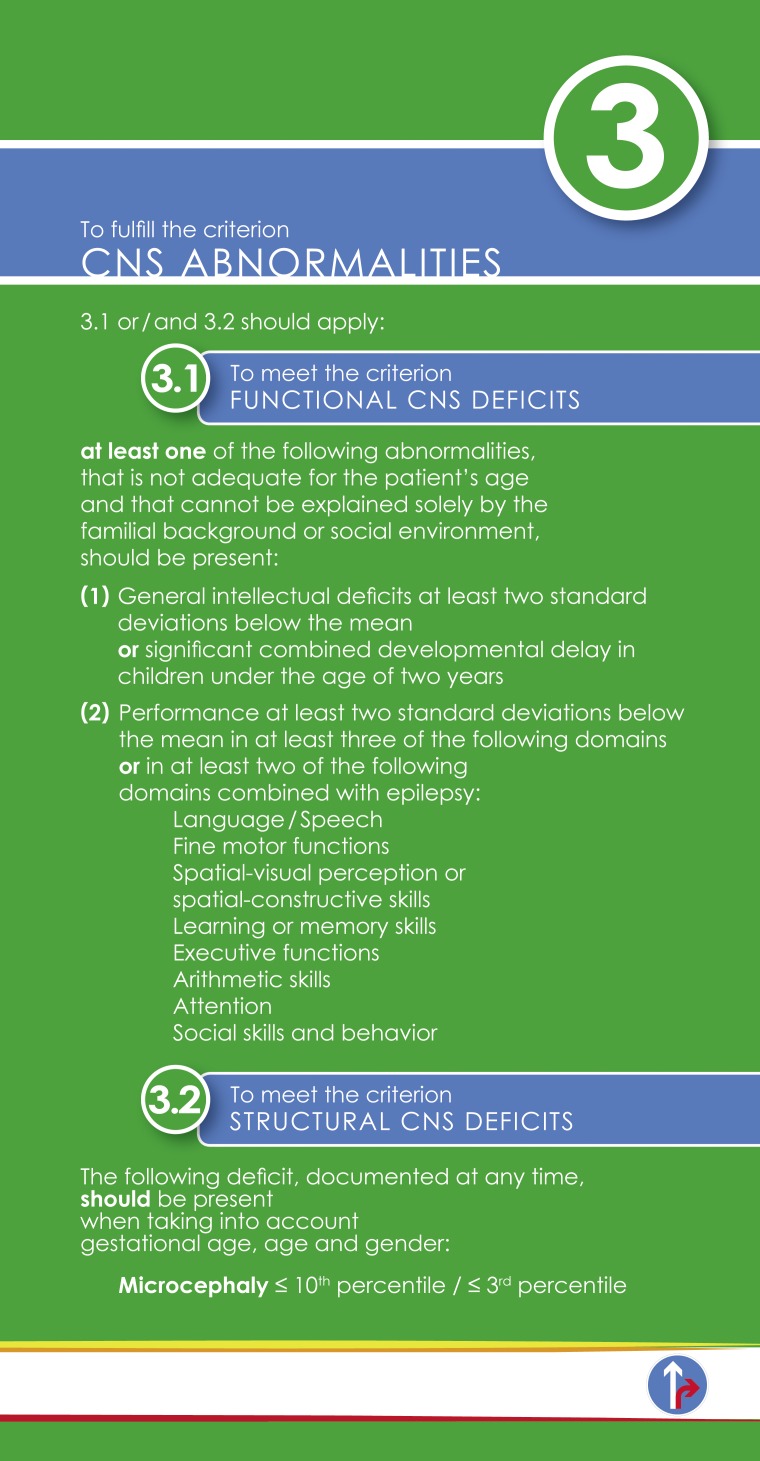

R 4: Abnormalities of the CNS

Early injury of the brain by alcohol toxicity may be primarily manifested by pathological restriction of growth (microcephaly). The severe functional abnormalities shown by affected children and adolescents in their daily lives represent behavioral phenotypes of toxic damage to brain structures.

R 5: Functional abnormalities of the CNS

Most of the published studies on functional regions of the CNS in which children with full-blown FAS typically show below-average performance (17– 24) are exploratory case–control studies (exceptions: the cohort studies by Nash et al. [25], LoE 2b-, and Coles et al. [26], LoE3b-), corresponding to evidence level 4. On this basis no specific neuropsychological profile of children with FAS can currently be defined. The consensus-based recommendation in a child suspected to have FAS is therefore as follows: Functional abnormalities of the CNS should be evaluated by means of standardized neuropsychological tests together with behavioral assessment by a psychologist or physician (expert consensus).

Because alcohol affects the brain globally or multifocally, abnormalities in at least three aspects of the CNS are necessary for the diagnosis of FAS (expert consensus).

In a cohort composed of patients from two FAS centers (27), Bell et al. found that 5.9% of children and adults with FASD (FAS/pFAS n = 85, ARND n = 340) showed epilepsy (ecological study/registry study, LoE 2c). This is much higher than the 0.6% prevalence of epilepsy found in the normal population (National Survey of Children’s Health, n = 91 605, Russ et al. [28]). In the presence of epilepsy, FAS can therefore be diagnosed when only two or more functional regions of the CNS are affected (expert consensus).

R 6: Structural abnormalities of the CNS

Day et al. (cohort study, n = 580) (6) showed that the head circumference of children whose mothers had not stopped drinking alcohol during pregnancy (n = 375 in first trimester, n = 185 in third trimester) was lower than that of those without intrauterine exposure to alcohol (absolute difference 6.6 mm, LoE 2b). On prenatal sonography Handmaker et al. (29) found no absolute negative difference in head circumference among fetuses of mothers who continued to drink alcohol after finding out they were pregnant, but the head circumference of these fetuses was smaller in relation to abdominal circumference (cohort study; n = 51 versus alcohol abstinence n = 46) (LoE 2b).

There is no agreement in the literature of the past 10 years regarding a recorded cut-off value for microcephaly in children with FAS. The guideline group was unable to achieve consensus on this criterion. Thus, head circumference ≤ 3rd percentile and head circumference ≤ 10th percentile are both adjudged to fulfill the criteria for the diagnostic category “structural abnormalities of the CNS”.

Owing to the limited evidence on structural abnormalities of the CNS such as volume reduction of the cerebellum and thickening of the cortex (30– 35), the guideline group agreed that structural CNS abnormalities other than microcephaly cannot currently be used as criteria for the diagnosis of FAS.

R 7: Importance of the confirmation of maternal alcohol consumption for diagnosis

Burd et al. (36) investigated the importance of confirmation of alcohol consumption of the mother during pregnancy for the certainty of the diagnosis of FAS (retrospective cohort study: FAS n = 152, pFAS n = 151, no FAS n = 87; LoE 3b). In cases where maternal alcohol consumption could not be confirmed, sensitivity for the diagnosis FAS was higher (unconfirmed 89%, confirmed 85%), while specificity was lower (71.1% versus 82.4%). In other words, more children with FAS actually have FAS diagnosed when alcohol consumption by their mother is not confirmed. Given the existence of estimates that a large proportion of children with FAS in Germany do not have their disorder diagnosed, the guideline group accepted the low specificity of the diagnostic criterion “unconfirmed intrauterine alcohol exposure” (LoE 3b, recommendation grade A).

Discussion

The experience of experts and affected patients alike shows that many people with FAS in Germany go undiagnosed, although they display the typical signs, and thus fail to receive appropriate help. Many physicians and psychologists receive too little information about FAS during their education and advanced training and therefore do not give sufficient consideration to the possibility of FAS when assessing children with developmental disorders or adults with cognitive deficits or psychiatric disorders.

Primary goal

The primary goal of the German guideline group was to identify the best diagnostic criteria for children and adolescents with full-blown FAS as laid out in this article. The long and short versions of the guideline are available in German at www.awmf.org.

It remains difficult to conduct high-quality studies on FAS diagnosis:

The diagnosis of FAS often rests on information from the mother about her alcohol consumption or abstinence during pregnancy. “Social desirability bias” is to be expected, as is “recall bias” for pregnancies a long time in the past.

The validation of diagnostic criteria for FAS is often tested on children who have already been diagnosed with FAS. There is thus no independent reference standard (“incorporation bias”).

In the studies published to date, various diagnostic instruments (e.g., the Institute of Medicine criteria and the 4-Digit Diagnostic Code) have been used to identify patients with FAS. These instruments feature various diagnostic criteria and cut-offs (e.g., head circumference percentile, number of facial characteristics, consideration of functional CNS abnormalities) and thus display no consistent diagnostic discrimination.

In light of these methodological difficulties, the systematically evaluated diagnostic recommendations for FAS presented here are based on the evidence-rated literature and on formal consensus of the representative multidisciplinary guideline group.

The diagnosis of FAS is complex:

Documentation of maternal alcohol intake is difficult. On the one hand many mothers are not questioned about their alcohol consumption during pregnancy because the physicians or midwives caring for them are worried about loss of trust or even a complete breakdown of the relationship. On the other, mothers frequently give inaccurate answers for reasons of social acceptability. Many children with FAS in Germany live in adoptive and foster families, so the information that can be obtained about the biological parents is often rudimentary. No adequately validated, objective measures for alcohol consumption during the entire pregnancy have yet been identified.

A further problem in diagnosis is that the characteristic abnormalities in children with FAS change with age (37). Typically, the facial abnormalities and growth deficiencies are obvious in childhood but less distinct in adolescence and adulthood. In contrast, while very young children with FAS often show little in the way of functional abnormalities of the CNS, adolescents almost always exhibit disorders of behavior, attention, and executive functions (higher cognitive adaptive processes). In early infancy the diagnosis of FAS frequently depends on detailed assessment by an experienced developmental neurologist. In later childhood and adolescence an indispensable role is played by complex psychological evaluation, because knowledge of the impairments in functional regions of the CNS is essential not only for diagnosing FAS but also in providing appropriate individual support, improving functional performance in daily life, and raising the quality of life of the affected adolescents and their families.

The neuropsychological tests proposed in the guideline provide a practical means of assessing the functional regions of the CNS that are typically affected in FAS.

Secondary goal

The second aim was to promote awareness among professionals of the existence of a professional support system and to increase knowledge of the typical characteristics of children and adolescents with FAS. Only with the assistance of specifically trained, experienced helpers in the health and social system can there be adequate education of society regarding the life-altering consequences of maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

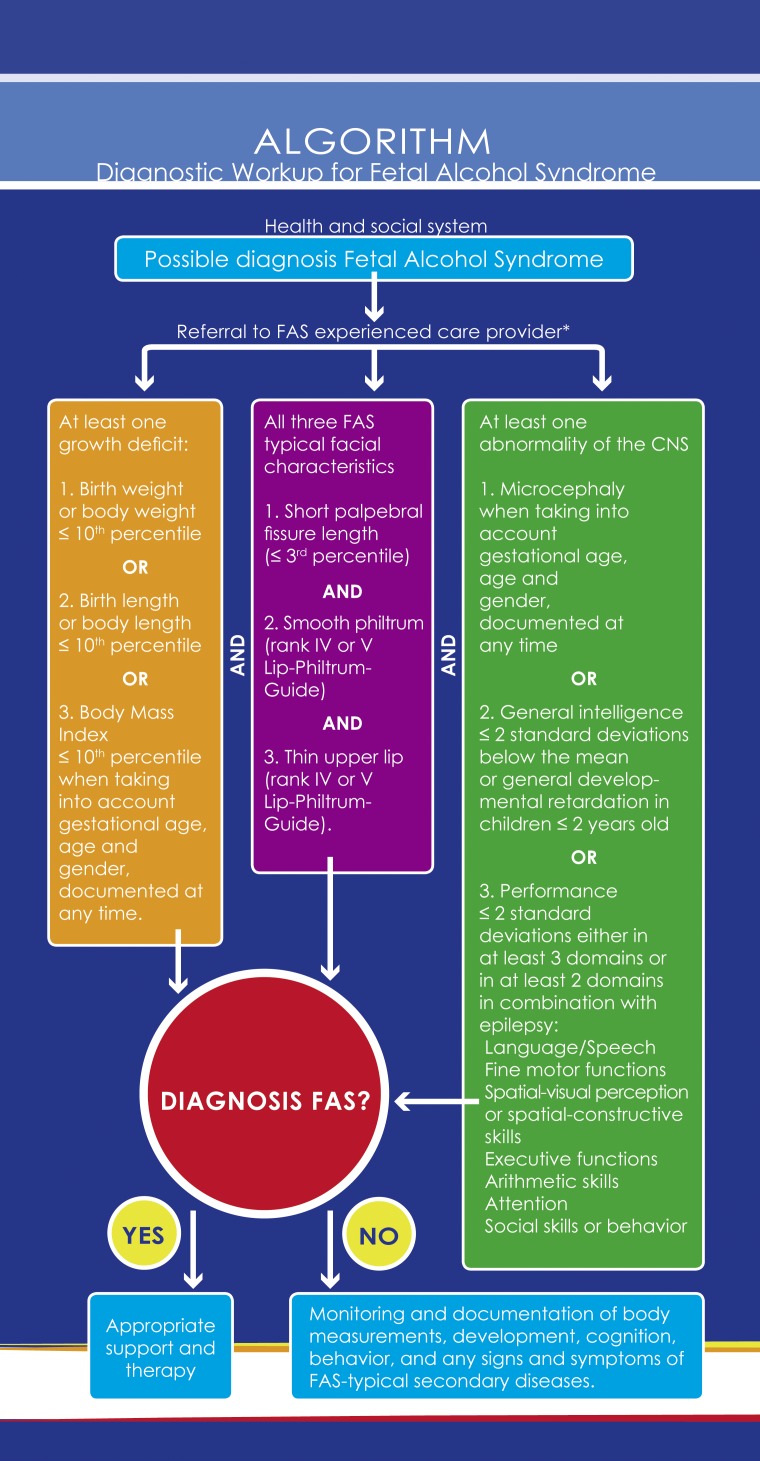

An “FAS Pocket Guide” has been compiled to provide practical orientation for physicians and institutions (eSupplement). A simple algorithm depicts the diagnostic procedure in the case of suspicion of FAS. Differential diagnoses are listed for each diagnostic category. Links are given to websites providing further information on prevention of alcohol consumption in pregnancy and support services for people with FAS and their families.

Because of the limited evidence available from the research carried out to date, this guideline had to be restricted to full-blown FAS in children and adolescents. The guideline group is fully aware of the importance of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders—whose prevalence is estimated by experts to be several times higher than that of FAS alone. FASD is harder to diagnose owing to the patients’ inconspicuous appearance, yet the problems they face in daily life are just as great as in FAS (6). This leaves a gap that can only be filled by initiatives in research and in the care of people affected by FAS and FASD.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

We are grateful to all participants in this guideline project for their constructive and efficient support and cooperation (eTable 1). Special thanks are due to Dipl.-Psych. Penelope Thomas and Dipl.-Psych. Jessica Wagner for their help in evaluating the quality criteria of the neuropsychological tests and to the staff of both the Agency for Quality in Medicine and the AWMF Institute for Management of Medical Knowledge for advice and support in conducting the study.

The study received financial support from the Federal Ministry of Health (BMG), the Society of Neuropediatrics (GNP), and the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.May. Epidemiology of FASD in a province in Italy: Prevalence and characteristics of children in a random sample of schools. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1562–1575. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.May. Prevalence of children with severe fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in communities near Rome, Italy: new estimated rates are higher than previous estimates. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:2331–2351. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8062331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergmann. Perinatale Einflussfaktoren auf die spätere Gesundheit - Ergebnisse des Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurveys (KiGGS) Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz. 2007;50:670–676. doi: 10.1007/s00103-007-0228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Barr HM, Sampson PD, O’Malley K, Young JK. Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:228–238. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200408000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klug MG, Burd L, Martsolf JT, Ebertowski M. Body mass index in fetal alcohol syndrome. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2003;25:689–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2003.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day NL, Leech SL, Richardson GA, Cornelius MD, Robles N, Larkby C. Prenatal alcohol exposure predicts continued deficits in offspring size at 14 years of age. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1584–1591. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000034036.75248.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones KL, Smith DW, Hanson JW. The fetal alcohol syndrome: clinical delineation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;273:130–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb52873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarren SK, Sampson PD, Larsen J, et al. Facial effects of fetal alcohol exposure: assessment by photographs and morphometric analysis. Am J Med Genet. 1987;26:651–666. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320260321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Astley SJ, Clarren SK. A fetal alcohol syndrome screening tool. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1565–1571. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Astley SJ, Clarren SK. Diagnosing the full spectrum of fetal alcohol-exposed individuals: introducing the 4-digit diagnostic code. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35:400–410. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Astley SJ. FAS Diagnostic and Prevention Network, University of Washington: Diagnostic guide for fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: the 4-digit diagnostic code. Available from: depts.washington.edu/fasdpn/pdfs/guide2004.pdf. (3rd ed. 2004) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarren SK, Chudley AE, Wong L, Friesen J, Brant R. Normal distribution of palpebral fissure lengths in Canadian school age children. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;17:e67–e78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Astley SJ. Canadian palpebral fissure length growth charts reflect a good fit for two school and FASD clinic-based US. populations .J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2011;18:e231–e241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strömland K, Chen Y, Norberg T, Wennerström K, Michael G. Reference values of facial features in Scandinavian children measured with a range-camera technique. Scand J Plast Reconstr Hand Surg. 1999;33:59–65. doi: 10.1080/02844319950159631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas IT, Gaitantzis YA, Frias JL. Palpebral fissure length from 29 weeks gestation to 14 years. J Pediatr. 1987;111:267–268. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall JG, Froster-Iskenius UG. Allanson J, editor. Handbook of normal physical measurements. Oxford. Oxford University Press. 1989:149–150. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattson SN, Roesch SC, Fagerlund A, et al. Toward a neurobehavioral profile of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1640–1650. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Astley SJ, Olson HC, Kerns K, et al. Neuropyschological and behavioral outcomes from a comprehensive magnetic resonance study of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;16:e178–e201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aragon AS, Coriale G, Fiorentino D, et al. Neuropsychological characteristics of Italian children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1909–1919. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorne JC, Coggins T. A diagnostically promising technique for tallying nominal reference errors in the narratives of school-aged children with Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2008:1–25. doi: 10.1080/13682820701698960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaurio L, Riley EP, Mattson SN. Neuropsychological Comparison of Children with Heavy Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and an IQ-Matched Comparison Group. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011;17:463–473. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711000063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pei J, Denys K, Hughes J, Rasmussen C. Mental health issues in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. J Ment Health. 2011;20:438–448. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.577113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasmussen C, Benz J, Pei J, et al. The impact of an ADHD co-morbidity on the diagnosis of FASD. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;17:e165–e176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fagerlund A, Utti-Ramo I, Hoyme HE, Mattson SN, Korkman M. Risk factors for behavioural problems in foetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:1481–1488. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nash K, Koren G, Rovet J. A differential approach for examining the behavioural phenotype of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2011;18:e440–e453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coles CD, Platzman KA, Lynch ME, Freides D. Auditory and visual sustained attention in adolescents prenatally exposed to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:263–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell SH, Stade B, Reynolds JN, et al. The remarkably high prevalence of epilepsy and seizure history in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1084–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russ SA, Larson K, Halfon N. A National profile of childhood epilepsy and seizure disorder. Pediatrics. 2012;129 doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Handmaker NS, Rayburn WF, Meng C, Bell JB, Rayburn BB, Rappaport VJ. Impact of alcohol exposure after pregnancy recognition on ultrasonographic fetal growth measures. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:892–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Gamst A, Riley EP, Mattson SN, Jernigan TL. Brain dysmorphology in individuals with severe prenatal alcohol exposure. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:148–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geuze E, Vermetten E, Bremner JD. MR-based in vivo hippocampal volumetrics: 2. Findings in neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:160–184. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sowell ER, Mattson SN, Kan E, Thompson PM, Riley EP, Toga AW. Abnormal cortical thickness and brain-behavior correlation patterns in individuals with heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:136–144. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Astley SJ, Aylward EH, Olson HC, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging outcomes from a comprehensive magnetic resonance study of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1671–1689. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bjorkquist OA, Fryer SL, Reiss AL, Mattson SN, Riley EP. Cingulate gyrus morphology in children and adolescents with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2010;181:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y, Roussotte F, Kan E, et al. Abnormal Cortical Thickness Alterations in Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders and Their Relationships with Facial Dysmorphology. Cereb Cortex. 2011;22:1170–1179. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burd L, Klug MG, Li Q, Kerbeshian J, Martsolf JT. Diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: a validity study of the fetal alcohol syndrome checklist. Alcohol. 2010;44:605–614. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spohr HL, Steinhausen HC. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and their persisting sequelae in adult life. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105:693–698. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]