Abstract

Purpose

We investigated the association between prevalence of symptoms and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in adult survivors of childhood cancer enrolled in the St Jude Lifetime Cohort study.

Methods

Eligibility criteria include childhood malignancy treated at St Jude, survival ≥ 10 years from diagnosis, and current age ≥ 18 years. Study participants were 1,667 survivors (response rate = 65%). Symptoms were self-reported by using a comprehensive health questionnaire and categorized into 12 classes: cardiac; pulmonary; motor/movement; pain in head; pain in back/neck; pain involving sites other than head, neck, and back; sensation abnormalities; disfigurement; learning/memory; anxiety; depression; and somatization. HRQOL was measured by using physical/mental component summary (PCS/MCS) and six domain scores of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey. Multivariable regression analysis was performed to investigate associations between symptom classes and HRQOL. Cumulative prevalence of symptom classes in relation to time from diagnosis was estimated.

Results

Pain involving sites other than head, neck and back, and disfigurement represented the most frequent symptom classes, endorsed by 58.7% and 56.3% of survivors, respectively. Approximately 87% of survivors reported multiple symptom classes. Greater symptom prevalence was associated with poorer HRQOL. In multivariable analysis, symptom classes explained up to 60% of the variance in PCS and 56% of the variance in MCS; demographic and clinical variables explained up to 15% of the variance in PCS and 10% of the variance in MCS. Longer time since diagnosis was associated with higher cumulative prevalence in all symptom classes.

Conclusion

A large proportion of survivors suffered from many symptom classes, which was associated with HRQOL impairment.

INTRODUCTION

With the introduction of new therapeutic strategies, the 5-year survival rate of childhood cancer has improved substantially.1 However, these survivors are at risk of developing long-term adverse sequelae related to cancer and/or cancer treatment.2 Traditionally, clinicians use laboratory-based toxicity and diagnostic information to evaluate adverse sequelae. In contrast, the use of patient-reported outcomes such as symptoms and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) that capture survivors' perception of cancer experience is less emphasized.

Symptoms are not synonymous with HRQOL. Symptoms represent a patient's perception of the occurrence of an abnormal physical, emotional, cognitive, or psychosomatic state, whereas HRQOL (or functional status) represents the impact of an event on a patient's daily function.3 Symptoms are proximal to the disease process and treatment exposure, and are one of the most important causative factors contributing to poor HRQOL.3 Symptoms and HRQOL assessment provide unique insight into health status and help design appropriate interventions for survivorship care.4

Research on symptom prevalence for adult survivors of childhood cancer is sparse5–8 compared with research on adult-onset cancer.9–11 Symptoms commonly investigated in long-term survivors of childhood cancer include fatigue, neurocognitive problems, pain, psychological distress, and sleep disturbance.6 Overall, 19% to 30% of survivors report fatigue7,8; 11% to 21% report memory and task efficiency problems12; 12% to 21% report pain13; 8% to 13% report psychological distress14,15; 14% report daytime sleepiness, and 17% report insomnia.7,8 Although these findings are compelling, they are incomplete because symptoms related to physical health (eg, organ function) have not been included.16,17

Scant research supports the association between symptom prevalence and HRQOL in long-term survivors of childhood cancer.5,8,18 The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) observed that survivors who reported more fatigue, sleep disturbance, and daytime sleepiness also reported greater HRQOL impairment than survivors with fewer symptoms.8 These studies emphasize the effect of individual symptoms on HRQOL rather than the effect of combined symptoms as a whole, leading to underestimating the overall impact of symptoms and limiting our ability to compare the relative contribution of individual symptom to HRQOL. If more symptoms are associated with poorer HRQOL, and large variance of HRQOL is explained by symptoms, it is important to identify symptoms and offer interventions to reduce symptom burden and, thereby, improve HRQOL.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the prevalence of a group of symptoms among long-term survivors enrolled in the St Jude Lifetime Cohort (SJLIFE) study, and to determine the association between symptom prevalence and HRQOL. We hypothesized there is a positive association between greater symptom prevalence and poorer HRQOL, and symptoms will account for greater variance in HRQOL than will demographic and clinical variables alone.

METHODS

Sample

The study sample includes 1,667 long-term survivors of childhood cancer who participated in SJLIFE, a follow-up study designed to understand etiologies and long-term adverse effects related to cancer treatments among childhood cancer survivors who were treated at St Jude Children's Research Hospital.19 During a St Jude campus visit, participants received comprehensive risk-based assessments consistent with the Children's Oncology Group's Long-term Follow-up Guidelines20 and completed comprehensive health questionnaires assessing behavioral, physical, psychosocial, and HRQOL outcomes.

Data Collection

Survivors eligible for study participation include those who were treated at St Jude for childhood cancer between 1962 and 2002, were ≥ 18 years old at enrollment onto SJLIFE, and had survived ≥ 10 years since the original cancer diagnosis.19 The SJLIFE study initiated enrollment of participants in November of 2007. As of March 2011, 4,127 potentially eligible participants were identified, and a recruitment package was sent to 3,186 survivors who met the enrollment criteria and had addresses available. Of these, 903 refused participation or were lost to follow-up, 616 agreed to participate but were not yet scheduled for a St Jude campus visit, and 1,667 completed the survey measures. The survey response rate was 65% (adjusting for those not yet scheduled for St Jude visits). The SJLIFE protocol was approved by St Jude's institutional review board.

Measurement

The symptom measures used in this study were adapted from those used in CCSS and have been reported in numerous peer-reviewed publications since 1992.19,21 Specific symptoms were designed to assess risk-based toxicities as outlined in the Children's Oncology Group guidelines20 and have demonstrated sensitivity to treatment exposures.6 For example, cranial radiation is related to the risk of emotional15,22 and cognitive symptoms,23 and thoracic radiation is related to cardiopulmonary symptoms.24 Twelve symptom classes were constructed, including nine classes for physical symptoms and three for psychological distress (Appendix Table A1, online only). In the comprehensive health questionnaire, 41 items measuring human organ impairment were categorized into nine physical symptom classes on the basis of homogeneity in content: cardiac symptoms (three items); pulmonary symptoms (three items); motor/movement problems (five items); pain in head (three items); pain in back/neck (two items); pain involving sites other than head, neck, and back (seven items); sensation abnormalities (10 items); disfigurement (seven items); and learning/memory problems (one item). For each item, three response categories (“yes, the condition is still present,” “yes, but the condition is no longer present,” and “no”) were used. Symptom presence was denoted if participants endorsed “yes, the condition is still present” for any item measuring that particular symptom. Symptom status was asked in general rather than in relation to cancer and treatment.

The Brief Symptoms Inventory-1825 was used to measure psychological distress. The Brief Symptoms Inventory-18 classifies distress into three symptom classes: anxiety (six items), depression (six items), and somatization (six items). For each item, a five-point Likert scale (0 = not at all; 4 = extremely) was used to explore the degree to which symptoms were bothersome during the past 7 days. A summated item score of a particular symptom class was calculated and converted to a T-score (mean = 50 and standard deviation [SD] = 10), and a meaningful cutoff (T-score ≥ 63, representing the lower 10th percentile of population norms) was used to denote the presence of a symptom class.25

HRQOL was measured by using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36).26 The SF-36 comprises eight HRQOL domains: physical functioning, role limitations resulting from physical health problems, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations resulting from emotional problems, and mental health. Domain scores of each participant were calculated with a range from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). Because the content of some items measuring BP and MH may overlap with some items measuring pain and psychological distress symptoms, we excluded BP and MH domains from the analysis to avoid overestimating the relationships. The physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) were calculated to represent physical and mental summary HRQOL. PCS and MCS were the normalized scores of a representative population with a mean = 50 and a SD = 10.26

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report the prevalence of 12 symptom classes. Multivariable analyses were performed to analyze the association of symptom classes with PCS, MCS, and six HRQOL domains. Three multiple linear regression models were performed: model 1 includes demographic (age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education) and clinical (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, amputation, second cancer, and year since diagnosis) variables as independent variables; model 2 includes 12 symptom classes as independent variables; model 3 includes demographic and clinical variables and 12 symptom classes as independent variables. We, however, did not include types of cancer in the analysis because types of cancer were highly correlated with types of treatment, and types of treatment were more often associated with late effects.14 The association of symptoms with HRQOL was estimated by regression coefficients, and the extent to which variance in HRQOL was explained by symptoms. In addition, cumulative prevalence of individual symptom class was estimated by referring time since cancer diagnosis to the presence of symptoms at the time of survey on the basis of the cross-sectional data collected from all cancer survivors.27 Cumulative prevalence was estimated by SAS CUMINCID macro and the remaining analyses by STATA 10.0.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 shows the participant characteristics. Of 1,667 participants, 51.5% were women and 84.3% were white, non-Hispanic. Mean age at survey was 33.7 years, and mean time since cancer diagnosis was 25.5 years. Cancer diagnosis includes CNS tumors (7.9%), leukemia (47.1%), lymphoma (18.5%), and solid tumors (26.5%). Cancer treatment includes chemotherapy (88.1%), radiotherapy (66.3%), and amputation (4%).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N = 1,667)

| Characteristic | Mean | SD, Range, or No. |

|---|---|---|

| Age at interview, years | 33.7 | 8.2, 18.9-63.3 |

| Time since diagnosis, years | 25.5 | 7.8, 11.0-48.0 |

| 10-19 | 411 | 24.7 |

| 20-29 | 760 | 45.6 |

| 30-39 | 423 | 25.4 |

| 40+ | 73 | 4.4 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 809 | 48.5 |

| Female | 858 | 51.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1,406 | 84.3 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 181 | 10.9 |

| Hispanic | 46 | 2.8 |

| Other | 34 | 2.0 |

| Educational background | ||

| Below high school | 159 | 10.1 |

| High school graduate/general education development | 316 | 20.1 |

| Some college/training after high school | 493 | 31.3 |

| College graduate | 424 | 26.9 |

| Post graduate level | 134 | 8.5 |

| Other | 48 | 3.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/living with a partner | 837 | 66.4 |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 215 | 17.1 |

| Single | 209 | 16.6 |

| Employment status | ||

| Ever had a job | 1,531 | 95.2 |

| Never had a job | 78 | 4.9 |

| Insurance status | ||

| Insured | 1,253 | 78.0 |

| Uninsured | 354 | 22.0 |

| Annual household incomes | ||

| <$19,999 | 280 | 19.7 |

| $20,000-$39,999 | 362 | 25.4 |

| $40,000-$59,999 | 261 | 18.3 |

| $60,000-$79,999 | 197 | 13.8 |

| $80,000-$99,999 | 134 | 9.4 |

| ≥$100,000 | 189 | 13.3 |

| Cancer diagnosis | ||

| Central nervous system tumors | 131 | 7.9 |

| Leukemia | 786 | 47.1 |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 742 | 44.5 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 36 | 2.2 |

| Other leukemia | 8 | 0.5 |

| Lymphoma | 308 | 18.5 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 249 | 14.9 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 59 | 3.5 |

| Solid tumors | 442 | 26.5 |

| Ewing sarcoma family of tumors | 55 | 3.3 |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | 11 | 0.7 |

| Neuroblastoma | 59 | 3.5 |

| Osteosarcoma | 68 | 4.1 |

| Retinoblastoma | 66 | 4.0 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 46 | 2.8 |

| Wilms tumor | 81 | 4.9 |

| Other solid tumors | 56 | 3.3 |

| Second cancer | ||

| Yes | 243 | 14.9 |

| No | 1,384 | 85.1 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 1,469 | 88.1 |

| No | 198 | 11.9 |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| Yes | 1,105 | 66.3 |

| No | 562 | 33.7 |

| Amputation | ||

| Yes | 66 | 4.0 |

| No | 1,601 | 96.0 |

Prevalence of Symptom Classes

Table 2 shows the prevalence of symptom classes. Two symptom classes were reported by more than 50% of the participants: pain involving sites other than head, neck, and back (58.7%) and disfigurement (56.3%). Three symptom classes were reported by 30% to 50% of the participants: pain in back/neck (48.5%), pain in head (35.9%), and sensation abnormalities (34.2%). The remaining seven symptom classes were reported by < 30% of the participants. For symptom counts, approximately 8% of the participants reported no symptoms, whereas 73% of participants reported 1 to 5 symptom classes, and 19% reported more than five symptom classes.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Symptom Classes in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer

| Individual Symptom Class | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Cardiac symptoms | 17.0 |

| Pulmonary symptoms | 7.3 |

| Motor/movement problems | 17.7 |

| Pain in head | 35.9 |

| Pain in back/neck | 48.5 |

| Pain involving sites other than head, neck, and back | 58.7 |

| Sensation abnormalities | 34.2 |

| Disfigurement | 56.3 |

| Learning/memory problems | 26.9 |

| Anxiety | 13.1 |

| Depression | 15.8 |

| Somatization | 19.3 |

| Count of symptom classes | |

| 0 | 8.4 |

| 1 | 15.1 |

| 2 | 17.3 |

| 3 | 17.5 |

| 4 | 12.3 |

| 5 | 10.6 |

| 6 | 5.5 |

| 7 | 4.6 |

| 8 | 3.7 |

| 9 | 2.6 |

| 10 | 1.5 |

| 11 | 1.0 |

| 12 | 0.1 |

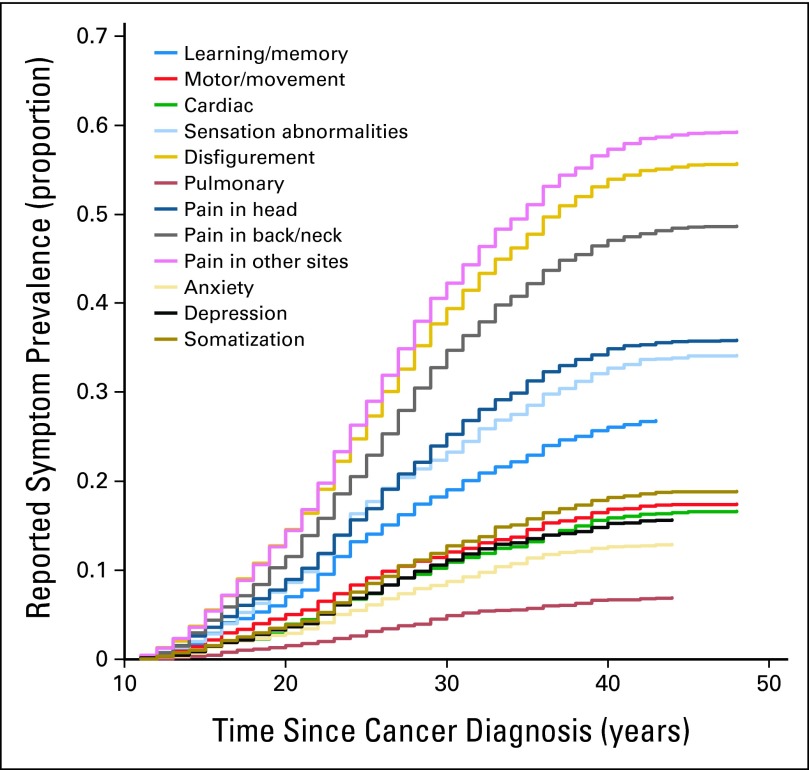

Figure 1 shows the cumulative prevalence of individual symptom class since time from diagnosis. The curves suggest an increased time from cancer diagnosis was associated with an increased prevalence. For all symptoms, the prevalence increased significantly from year 10 to 30, though tended to slow after 30 years. The 40-year cumulative prevalence was highest for pain involving sites other than head, neck, and back (57.2%), followed by disfigurement (54.1%).

Fig 1.

Cumulative prevalence of symptom class since time from diagnosis. The cumulative prevalence of symptom class presented in this figure is estimated based on the cross-sectional data that suggests cancer survivors who survive longer after diagnosis tend to report higher symptom prevalence.

Association Between Symptom Prevalence and HRQOL

Table 3 shows the results of multivariable analyses for the associations of 12 symptom classes and physical/mental summary HRQOL. Overall, each symptom class was significantly associated with impaired PCS and MCS (P < .05), except pulmonary symptoms with MCS. Participants with higher education levels had better PCS and MCS than those with lower education. Having chemotherapy and radiotherapy was statistically associated with impaired PCS but not MCS (P > .05). The change in regression coefficients of demographic and clinical variables associated with HRQOL before (model 1) and after (model 3) the inclusion of symptom classes was larger as compared with the change in regression coefficients of symptom classes associated with HRQOL before (model 2) and after (model 3) the inclusion of demographic and clinical variables. This finding was replicated across six HRQOL domains. Inclusion of 12 symptom classes alone (model 2) explained up to 60% and 56% of the variance in PCS and MCS, respectively, whereas demographic and clinical variables (model 1) explained variance in PCS and MCS up to 15% and 10%, respectively. Variance in PCS and MCS commonly shared by demographic/clinical variables and symptom classes was approximately 12% and 8%, respectively.

Table 3.

Association of Symptom Class Prevalence and Physical/Mental Component Summary of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Multivariable Analyses

| Variable | Physical Component Summary |

Mental Component Summary |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1/Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 1/Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||||

| Beta | P | Beta | P | Beta | P | Beta | P | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| Age | −0.22 | < .001 | −0.08 | .009 | −0.14 | .002 | −0.02 | .623 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | −1.96 | < .001 | −0.39 | .228 | −2.94 | < .001 | −1.86 | < .001 |

| Race/ethnicity (Reference: white) | ||||||||

| Black | −1.14 | .127 | −1.80 | .001 | 0.35 | .651 | −0.59 | .288 |

| Hispanic | 1.57 | .261 | −0.38 | .698 | 2.64 | .068 | 0.66 | .524 |

| Other (NA, AS, PI, etc.) | 2.65 | .104 | 1.24 | .265 | 2.71 | .108 | 0.54 | .644 |

| Education (Reference: below HS) | ||||||||

| HS/GED | 3.75 | < .001 | 2.53 | < .001 | 3.03 | .002 | 1.66 | .015 |

| Training after HS/some college | 6.51 | < .001 | 4.07 | < .001 | 5.27 | < .001 | 2.94 | < .001 |

| College graduate | 8.49 | < .001 | 4.33 | < .001 | 7.17 | < .001 | 3.27 | < .001 |

| Post-graduate | 10.19 | < .001 | 4.86 | < .001 | 8.61 | < .001 | 3.35 | < .001 |

| Other | 3.65 | .001 | 3.03 | < .001 | 2.91 | .010 | 3.32 | < .001 |

| Years since diagnosis | 0.06 | .185 | 0.02 | .512 | 0.06 | .210 | <0.01 | .760 |

| Second cancer | −2.93 | < .001 | −0.85 | .060 | −2.06 | .002 | −0.41 | .389 |

| Chemotherapy | −0.36 | .607 | −1.05 | .029 | −0.24 | .738 | −0.77 | .132 |

| Radiotherapy | −1.86 | < .001 | −1.09 | .003 | −1.26 | .020 | −0.39 | .305 |

| Amputation | −3.02 | .016 | −1.27 | .141 | 0.03 | .984 | 1.14 | .212 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||

| Symptom class | ||||||||

| Cardiac symptoms | −4.12 | < .001 | −3.51 | < .001 | −2.27 | < .001 | −1.75 | < .001 |

| Pulmonary symptoms | −1.98 | .003 | −1.46 | .029 | −0.34 | .625 | −0.33 | .643 |

| Motor/movement problems | −4.36 | < .001 | −4.19 | < .001 | −0.99 | .044 | −0.94 | .055 |

| Pain in head | −1.41 | < .001 | −1.47 | < .001 | −2.59 | < .001 | −2.24 | < .001 |

| Pain in back/neck | −2.58 | < .001 | −2.53 | < .001 | −2.06 | < .001 | −2.06 | < .001 |

| Pain in other sites* | −3.30 | < .001 | −3.18 | < .001 | −1.92 | < .001 | −1.84 | < .001 |

| Sensation abnormalities | −1.81 | < .001 | −1.86 | < .001 | −1.31 | .001 | −1.38 | < .001 |

| Disfigurement | −2.48 | < .001 | −2.29 | < .001 | −2.08 | < .001 | −2.03 | < .001 |

| Learning/memory problems | −1.72 | < .001 | −1.47 | < .001 | −2.04 | < .001 | −1.49 | < .001 |

| Anxiety | −1.84 | .002 | −1.57 | .006 | −4.28 | < .001 | −4.25 | < .001 |

| Depression | −3.84 | < .001 | −3.88 | < .001 | −8.93 | < .001 | −9.22 | < .001 |

| Somatization | −4.96 | < .001 | −4.57 | < .001 | −3.13 | < .001 | −2.92 | < .001 |

| Variance, % | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 15.0 | 10.1 | ||||||

| Model 2 | 60.0 | 56.0 | ||||||

| Model 3 | 62.5 | 58.1 | ||||||

NOTE. Model 1 only includes demographic and clinical variables as independent variables; Model 2 only includes 12 symptom classes as independent variables; and Model 3 includes demographic and clinical variables plus 12 symptom classes as independent variables.

Abbreviations: AS, Asian; GED, general education development; HS, high school; NA, Native American; PI, Pacific Islander.

Pain involving sites other than head, neck, and back.

P < .05.

P < .01.

P < .001.

Table 4 shows the association of 12 symptom classes with six HRQOL domains on the basis of multivariable analyses. The prevalence of cardiac symptoms, motor/movement problems, pain involving sites other than head, neck, and back, sensation abnormalities, disfigurement, depression, and somatization was significantly associated with impairment in the majority of HRQOL domains. Specifically, pain involving sites other than head, neck, and back, sensation abnormalities, disfigurement, learning/memory problems, and somatization were associated with impairment in all six HRQOL domains (P < .05); the only exceptions were pain involving sites other than head, neck, and back, and sensation abnormalities with RE (P > .05). Cardiac symptoms and motor/movement problems were associated with impaired physical aspects of HRQOL (physical functioning, role limitations resulting from physical health problems, and general health perceptions; P < .05). Anxiety and depression were associated with impaired mental aspects of HRQOL (vitality, social functioning, and RE; P < .05).

Table 4.

Association of Symptom Class Prevalence and Six Domains of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Multivariable Analyses

| Variable | Physical Functioning |

Role Limitations Resulting From Physical Health Problems |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1/Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 1/Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||||

| Beta | P | Beta | P | Beta | P | Beta | P | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| Age | −0.21 | < .001 | −0.12 | .005 | −0.21 | < .001 | −0.11 | .017 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | −1.44 | .004 | −0.27 | .540 | −0.62 | .243 | 0.77 | .097 |

| Race/ethnicity (Reference: white) | ||||||||

| Black | −4.02 | < .001 | −4.38 | < .001 | −2.46 | .005 | −2.92 | < .001 |

| Hispanic | 0.34 | .824 | −1.27 | .341 | 1.90 | .246 | < 0.01 | .995 |

| Other (NA, AS, PI, etc.) | 2.51 | .158 | 1.46 | .333 | 3.82 | .043 | 2.28 | .148 |

| Education (Reference: below HS) | ||||||||

| HS/GED | 4.43 | < .001 | 3.84 | < .001 | 5.01 | < .001 | 4.39 | < .001 |

| Training after HS/some college | 7.93 | < .001 | 6.15 | < .001 | 7.52 | < .001 | 5.55 | < .001 |

| College graduate | 9.51 | < .001 | 6.33 | < .001 | 9.52 | < .001 | 5.93 | < .001 |

| Post-graduate | 10.85 | < .001 | 7.08 | < .001 | 11.28 | < .001 | 6.96 | < .001 |

| Other | 5.13 | < .001 | 3.88 | .001 | 3.21 | .012 | 2.12 | .071 |

| Years since diagnosis | 0.03 | .564 | <0.01 | .984 | 0.05 | .331 | 0.03 | .530 |

| Second cancer | −3.16 | < .001 | −1.25 | .044 | −2.92 | <.001 | −0.94 | .148 |

| Chemotherapy | −0.69 | .375 | −1.58 | .017 | −0.55 | .501 | −1.55 | .025 |

| Radiotherapy | −2.50 | < .001 | −1.59 | .001 | −2.04 | .001 | −0.91 | .081 |

| Amputation | −7.88 | < .001 | −6.52 | < .001 | −3.49 | .017 | −1.75 | .158 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||

| Symptom class | ||||||||

| Cardiac symptoms | −5.53 | < .001 | −4.72 | < .001 | −3.11 | < .001 | −2.54 | < .001 |

| Pulmonary symptoms | −3.33 | <.001 | −2.15 | .018 | −1.98 | .039 | −1.13 | .235 |

| Motor/movement problems | −6.66 | < .001 | −6.30 | < .001 | −6.46 | < .001 | −6.30 | < .001 |

| Pain in head | 0.92 | .059 | 0.61 | .196 | 0.17 | .735 | −0.14 | .777 |

| Pain in back/neck | −1.19 | .014 | −1.09 | .019 | −0.84 | .088 | −0.70 | .151 |

| Pain in other sites* | −1.44 | .004 | −1.24 | .009 | −1.85 | < .001 | −1.77 | < .001 |

| Sensation abnormalities | −1.88 | < .001 | −2.00 | < .001 | −1.64 | .002 | −1.73 | .001 |

| Disfigurement | −2.73 | < .001 | −2.28 | < .001 | −2.54 | < .001 | −2.32 | < .001 |

| Learning/memory problems | −1.33 | .013 | −1.32 | .011 | −2.05 | < .001 | −1.94 | < .001 |

| Anxiety | −1.35 | .103 | −0.63 | .424 | −2.20 | .009 | −1.72 | .038 |

| Depression | −1.10 | .139 | −1.38 | .052 | −3.19 | < .001 | −3.16 | < .001 |

| Somatization | −3.65 | < .001 | −3.06 | <.001 | −5.34 | < .001 | −4.83 | < .001 |

| Variance, % | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 17.0 | 12.6 | ||||||

| Model 2 | 35.2 | 37.5 | ||||||

| Model 3 | 43.1 | 41.7 | ||||||

| Variable | General Health Perceptions |

Vitality |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1/Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 1/Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||||

| Beta | P | Beta | P | Beta | P | Beta | P | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| Age | −0.18 | .001 | −0.03 | .463 | −0.20 | < .001 | −0.07 | .114 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | −2.29 | < .001 | −0.65 | .175 | −4.26 | < .001 | −3.07 | < .001 |

| Race/ethnicity (Reference: white) | ||||||||

| Black | −0.16 | .866 | −0.57 | .460 | 2.60 | .003 | 1.78 | .014 |

| Hispanic | 1.18 | .497 | −0.78 | .591 | 3.54 | .028 | 1.51 | .264 |

| Other (NA, AS, PI, etc.) | 2.12 | .286 | 1.25 | .445 | 3.27 | .076 | 1.47 | .336 |

| Education (Reference: below HS) | ||||||||

| HS/GED | 2.07 | .069 | 0.02 | .982 | 2.10 | .047 | 0.65 | .456 |

| Training after HS/some college | 5.27 | < .001 | 1.96 | .027 | 3.98 | < .001 | 1.82 | .028 |

| College graduate | 7.27 | < .001 | 2.30 | .011 | 6.01 | < .001 | 2.33 | .006 |

| Post-graduate | 8.48 | < .001 | 2.28 | .042 | 7.15 | < .001 | 2.17 | .038 |

| Other | 3.49 | .009 | 2.83 | .019 | 3.03 | .015 | 3.69 | .001 |

| Years since diagnosis | 0.06 | .305 | 0.01 | .808 | 0.11 | .040 | 0.06 | .136 |

| Second cancer | −3.45 | < .001 | −1.29 | .054 | −1.63 | .029 | −0.04 | .945 |

| Chemotherapy | 0.30 | .732 | −0.27 | .706 | 0.07 | .935 | −0.54 | .417 |

| Radiotherapy | −2.61 | < .001 | −2.06 | < .001 | −0.85 | .162 | −0.19 | .704 |

| Amputation | −1.15 | .456 | 0.61 | .630 | 0.22 | .878 | 1.28 | .279 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||

| Symptom class | ||||||||

| Cardiac symptoms | −4.98 | < .001 | −4.49 | < .001 | −3.17 | < .001 | −2.50 | < .001 |

| Pulmonary symptoms | −3.22 | .001 | −3.25 | .001 | 0.32 | .724 | −0.05 | .959 |

| Motor/movement problems | −3.02 | < .001 | −2.78 | < .001 | −0.36 | .579 | −0.33 | .612 |

| Pain in head | −2.47 | < .001 | −2.45 | < .001 | −3.71 | < .001 | −3.06 | < .001 |

| Pain in back/neck | −2.06 | < .001 | −2.15 | < .001 | −2.41 | < .001 | −2.32 | < .001 |

| Pain in other sites* | −3.26 | < .001 | −3.25 | < .001 | −2.23 | < .001 | −2.08 | < .001 |

| Sensation abnormalities | −1.73 | .002 | −1.68 | .002 | −1.46 | .005 | −1.40 | .006 |

| Disfigurement | −2.46 | < .001 | −2.25 | < .001 | −2.66 | < .001 | −2.55 | < .001 |

| Learning/memory problems | −1.71 | .002 | −1.29 | .022 | −1.63 | .002 | −1.12 | .034 |

| Anxiety | −1.44 | .088 | −1.23 | .147 | −1.80 | .025 | −2.08 | .009 |

| Depression | −4.44 | < .001 | −4.52 | < .001 | −7.46 | < .001 | −7.90 | < .001 |

| Somatization | −5.41 | < .001 | −4.97 | < .001 | −3.18 | < .001 | −3.07 | < .001 |

| Variance, % | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 9.6 | 9.2 | ||||||

| Model 2 | 42.5 | 39.1 | ||||||

| Model 3 | 44.1 | 42.2 | ||||||

| Variable | Social Functioning |

Role Limitations Resulting From Emotional Problems |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1/Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 1/Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|||||

| Beta | P | Beta | P | Beta | P | Beta | P | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| Age | −0.11 | .040 | 0.01 | .872 | −0.08 | .181 | 0.01 | .787 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | −2.51 | < .001 | −1.35 | .002 | −1.79 | .002 | −0.91 | .073 |

| Race/ethnicity (Reference: white) | ||||||||

| Black | −2.01 | .021 | −2.77 | < .001 | −2.56 | .008 | −3.12 | < .001 |

| Hispanic | 1.64 | .317 | −0.45 | .736 | 3.49 | .052 | 1.59 | .306 |

| Other (NA, AS, PI, etc.) | 1.35 | .469 | −0.46 | .760 | 2.14 | .299 | 0.48 | .784 |

| Education (Reference: below HS) | ||||||||

| HS/GED | 3.89 | < .001 | 2.88 | .001 | 6.16 | < .001 | 5.19 | < .001 |

| Training after HS/some college | 6.10 | < .001 | 4.05 | < .001 | 7.40 | < .001 | 5.33 | < .001 |

| College graduate | 7.85 | < .001 | 4.11 | < .001 | 9.11 | < .001 | 5.69 | < .001 |

| Post-graduate | 9.17 | < .001 | 4.30 | < .001 | 10.86 | < .001 | 6.13 | < .001 |

| Other | 2.55 | .043 | 2.72 | .015 | 3.74 | .007 | 4.59 | < .001 |

| Years since diagnosis | 0.01 | .908 | −0.03 | .417 | −0.01 | .899 | −0.04 | .418 |

| Second cancer | −2.48 | .001 | −0.83 | .182 | −1.69 | .040 | −0.34 | .633 |

| Chemotherapy | 0.13 | .871 | −0.66 | .319 | −0.67 | .457 | −1.43 | .060 |

| Radiotherapy | −1.44 | .019 | −0.30 | .549 | −1.38 | .040 | −0.23 | .692 |

| Amputation | −0.55 | .705 | 0.49 | .677 | −0.15 | .927 | 0.16 | .909 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||

| Symptom class | ||||||||

| Cardiac symptoms | −2.48 | < .001 | −2.12 | < .001 | −1.64 | .023 | −1.13 | .120 |

| Pulmonary symptoms | −0.66 | .467 | 0.05 | .959 | −0.99 | .343 | −0.32 | .763 |

| Motor/movement problems | −2.07 | .001 | −1.96 | .002 | −2.05 | .005 | −2.16 | .003 |

| Pain in head | −1.58 | .001 | −1.35 | .005 | −0.99 | .065 | −0.85 | .118 |

| Pain in back/neck | −1.14 | .014 | −1.07 | .020 | −0.93 | .080 | −0.93 | .081 |

| Pain in other sites* | −1.77 | < .001 | −1.65 | .001 | −0.84 | .122 | −0.79 | .148 |

| Sensation abnormalities | −1.57 | .002 | −1.77 | < .001 | −0.89 | .127 | −0.99 | .088 |

| Disfigurement | −2.05 | < .001 | −2.06 | < .001 | −1.23 | .016 | −1.29 | .013 |

| Learning/memory problems | −2.62 | < .001 | −2.17 | < .001 | −2.58 | < .001 | −1.99 | .001 |

| Anxiety | −3.59 | < .001 | −3.44 | < .001 | −4.42 | < .001 | −4.03 | < .001 |

| Depression | −8.53 | < .001 | −8.73 | < .001 | −9.33 | < .001 | −9.65 | < .001 |

| Somatization | −3.73 | < .001 | −3.52 | < .001 | −3.00 | < .001 | −2.95 | < .001 |

| Variance, % | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 8.9 | 7.8 | ||||||

| Model 2 | 41.6 | 32.2 | ||||||

| Model 3 | 43.9 | 35.3 | ||||||

NOTE. Model 1 only includes demographic and clinical variables as independent variables; Model 2 only includes 12 symptom classes as independent variables; and Model 3 includes demographic and clinical variables plus 12 symptom classes as independent variables.

Abbreviations: AS, Asian; GED, general education development; HS, high school; NA, Native American; PI, Pacific Islander.

Pain involving sites other than head, neck, and back.

P < .05.

P < .01.

P < .001.

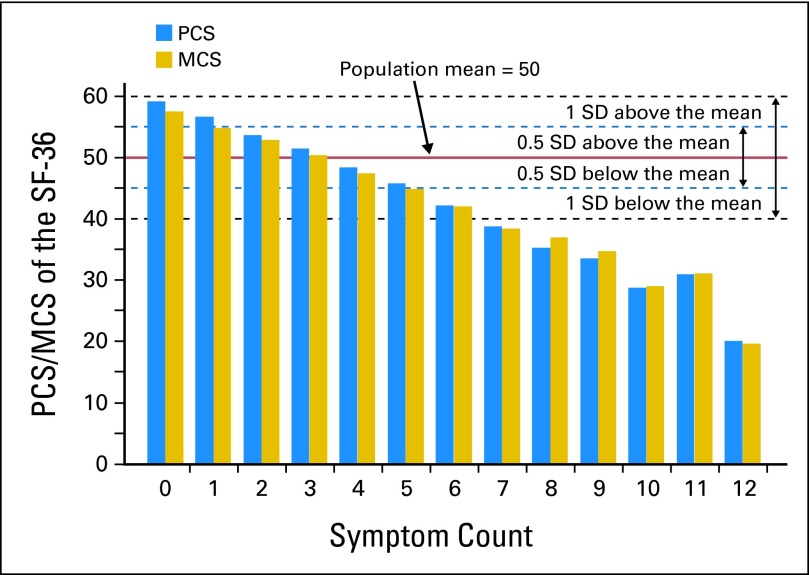

Figure 2 shows the associations between counts of symptom classes and PCS/MCS. Survivors with more symptom counts had a greater impairment in PCS and MCS compared with those with fewer symptom counts. If PCS = 45 and MCS = 45 were selected as cutoffs to represent clinically meaningful impairment28 (0.5 SD below population norm), it corresponds to approximately 30% of all participants reporting more than four symptom counts. For survivors with a symptom count more than four, relative to less than or equal to four, the odds ratios of PCS and MCS less than 45 were 15.5 (95% CI, 11.8 to 20.4) and 12.2 (95% CI, 9.4 to 15.8), respectively. If PCS = 40 and MCS = 40 were selected as cutoffs14,15 (1.0 SD below population norm), it corresponds to approximately 14% of all participants reporting more than six symptom counts. For survivors with a symptom count more than six, relative to less than or equal to six, the odds ratios of PCS and MCS less than 40 were 25.4 (95% CI, 17.8 to 36.3) and 18.1 (95% CI, 12.9 to 25.5), respectively.

Fig 2.

Association between count of symptom classes and physical/mental component summary (PCS/MCS) of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). SD, standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed a significant burden of chronic symptoms in long-term adult survivors of childhood cancer: 70% of participants reported one to six symptom classes, and 25% reported more than six symptom classes. Among 12 symptom classes, survivors reported high prevalence (> 50%) in pain involving sites other than head, neck, and back and disfigurement. It is evident that symptoms appear to be more prevalent on the basis of a comparison of the present results to reports on the general population of the same age range, although different studies might use different approaches to measure symptoms. For example, 49% of cancer survivors in this study had pain in back/neck and 36% had pain in head, whereas 13% to 29% of the US general population reported pain in neck/back and 20% reported pain in head.29 Importantly, symptom prevalence was significantly associated with impairment in different HRQOL domains. Multiple symptom classes explained up to 60% of the variance in PCS and MCS, compared with demographic and clinical variables, which explained up to 15% of the variance.

Although literature suggests symptoms are prevalent in survivors of adult-onset cancers through the trajectory for up to 10 years after primary treatment,30–32 little is known about symptom prevalence in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. This study revealed the cumulative prevalence for individual symptoms increased from 10 years since diagnosis up to 40 years, and then appeared to plateau. The mechanism behind the increase of symptom prevalence associated with the increase of time since diagnosis is unclear, yet our finding provides a foundation for understanding appropriate timing to screen presence of various symptoms in future studies.

A wealth of literature suggests that multiple symptoms (eg, depression, fatigue, pain, poor concentration, and sleep disturbance) co-occurred and were moderately correlated with each other in cancer survivors.33–36 In our study, symptoms of survivors occurred in multiples, with approximately 77% of participants reporting more than one symptom. In contrast, 40% to 61% of survivors of adult-onset cancer reported multiple symptoms.10 The presence of multiple symptoms may exacerbate or mediate the severity of one another,37 and a common biologic mechanism (eg, an inflammatory response) may contribute to the co-occurrence of some of these symptoms.38–41 Understanding the mechanisms behind symptom clusters is an important topic of future studies and may help in the design of appropriate interventions to control symptoms, presumably leading to better HRQOL.

Our study as one of the largest cohorts of adult survivors of childhood cancer provides a unique contribution to the existing literature.7,42–47 We demonstrate a significant and robust effect of symptoms on the impairment of different HRQOL domains. All symptom classes, except pulmonary, were significantly associated with poor PCS, MCS, and six HRQOL domains. Our finding is in line with previous CCSS studies suggesting that among childhood cancer survivors the presence of symptoms including fatigue, sleep disturbance, cognitive symptom, and psychological distress was significantly related to poorer HRQOL on the SF-36.8,48 Similar findings on the symptom presence associated with HRQOL impairment was observed in survivors of adult-onset cancers45,49 and individuals with AIDS/HIV,50 sickle cell disease,51 and those receiving hemodialysis.52 In addition, variance in HRQOL explained by 12 symptom classes in this study was larger (up to 60%) compared with other studies focusing on adult cancer survivors44,53,54 and patients without cancer.52,55 Interestingly, we found some symptoms with low prevalence (eg, cardiac symptoms, anxiety, and depression) had an equivalent impact on HRQOL as symptoms with moderate prevalence (eg, pain in head, pain in back/neck, and sensation abnormalities). This suggests the design of symptom tools needs to account for not only the symptom prevalence but also their severity related to HRQOL impact.

Evidence has been mixed in comparing HRQOL between childhood cancer survivors and general population (ie, better HRQOL,56,57 impaired HRQOL,58–61 or no difference62–64). This study suggests HRQOL comparisons might be confounded by the number of symptoms. We demonstrate that if a 0.5 SD rule was used,28 survivors with less than one and more than four symptom classes will have clinically meaningfully good and poor HRQOL, respectively, compared with the general population. If a 1.0 SD rule was used,14,15 survivors with none and more than six symptom classes will have significantly good and poor HRQOL, respectively, compared with the general population. Intuitively, the association between symptom counts and PCS/MCS appeared linear (Fig 2), suggesting that the effect of symptoms is additive rather subtractive or synergistic.

Self-reported symptoms and HRQOL are usually assessed separately in clinical practice without thoroughly investigating the possible linkage between symptom reduction and HRQOL improvement. The strong correlations of individual symptoms with HRQOL alongside large variation in HRQOL explained by symptoms suggest alleviating symptoms may be one avenue to improve HRQOL. Clinicians are encouraged to understand the complexity of symptoms and tailor individual interventions for survivors on the basis of the types of specific symptoms (eg, cognitive-behavior therapy65,66 for pain, depression, and fatigue, and physical training67,68 for fatigue and physical symptoms). Innovative methodologies (eg, diagnostic classification model69(p348)) can be used to classify survivors into different levels of HRQOL according to multiple symptoms that indicate HRQOL impairment.

Several limitations of this study are worth noting. First, the generalizability of our findings to other settings is limited because survivors were recruited from a single institution. Second, the reliance on cross-sectional data and the use of inconsistent time frames on the Brief Symptoms Inventory (a 7-day recall period) and SF-36 (a 4-week recall period) might make it impossible to determine a causal relationship between symptoms and HRQOL. Although we found that symptom presence appears to be increasing over time, we are not able to distinguish as to whether the increase results from cancer-, treatment-, or age-related symptomology. Longitudinal studies that include survivors and age-sex–matched noncancer populations are needed to understand the genuine cancer- or treatment-related symptoms while controlling for historical and aging factors. Third, the symptoms under investigation did not include fatigue and sleep disturbance, which are deemed important to survivors.5,6 Therefore, the extent that these symptoms are associated with HRQOL and the variance in HRQOL explained by the symptoms might be underestimated.

In conclusion, a large proportion of survivors enrolled in SJLIFE suffer from a variety of symptoms that adversely impact HRQOL. Measuring symptoms alone without measuring HRQOL or vice versa may result in failure to understand the full impact of cancer and its treatment. Appropriate interventions that target specific symptoms may improve survivors' HRQOL.

Appendix

Table A1.

Content of the Symptom Class Measure

| Symptom Class | Item |

|---|---|

| Cardiac symptoms | Irregular heartbeat or palpitations (arrhythmia) requiring medication or follow-up by a doctor |

| Angina pectoris (chest pains because of lack of oxygen to the heart requiring medication such as nitroglycerin) | |

| Does exercise cause severe chest pain, shortness of breath, or irregular heartbeat | |

| Pulmonary symptoms | Chronic cough or shortness of breath for more than 1 month |

| Emphysema | |

| Problem with breathing while at rest that lasted for more than 3 months | |

| Motor/movement problems | Problem with balance, equilibrium, or ability to reach for or manipulate objects |

| Tremors or problems with movement | |

| Weakness or inability to move arm | |

| Weakness or inability to move leg | |

| Paralysis of any kind | |

| Pain in head | Migraine |

| Severe headache | |

| Pain: head | |

| Pain in back/neck | Pain: back |

| Pain: neck | |

| Pain involving sites other than head, neck, and back | Prolonged pain in arms, legs, or back |

| Pain: chest | |

| Pain: hands/arms | |

| Pain: abdomen | |

| Pain: pelvis | |

| Pain: leg/feet | |

| Pain: other | |

| Sensation abnormalities | Hearing loss requiring a hearing aid |

| Decreased sense of touch or feeling in hands, fingers, arms, or leg | |

| Abnormal sensation in arms, legs, or back | |

| Persistent dizziness or vertigo | |

| Problem with double vision | |

| Crossed or turned eyes | |

| Trouble seeing with one or both eyes even when wearing glasses | |

| Very dry eyes requiring eye drops or ointment | |

| Abnormal sense of taste | |

| Loss of taste or smell lasting for 3 months or more | |

| Disfigurement | Persistent hair loss |

| Scaring or disfigurement of the head or neck regions | |

| Scaring or disfigurement of the chest or abdomen regions | |

| Scaring or disfigurement of the arms or legs | |

| Walk with limb | |

| Loss of an arm or a leg | |

| Loss of an eye | |

| Learning/memory problems | Problems with learning or memory |

| Psychological distress* | Anxious symptoms (six items) |

| Depressive symptoms (six items) | |

| Somatic symptoms (six items) |

NOTE. Sample question stems for pain symptoms: “For pain that you have had during the past 4 weeks, where has this pain been located: head (yes/no); neck (yes/no); chest (yes/no); arm (yes/no); leg (yes/no); etc.”; for psychological distress: “How much that problem has distressed or bothered you during the past 7 days including today: feeling blue (not at all/a little bit/moderately/quite a bit/extremely); feeling no interest in things (not at all/a little bit/moderately/quite a bit/extremely); feeling lonely (not at all/a little bit/moderately/quite a bit/extremely); etc.”

Data adapted.25

Footnotes

Supported by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant No. CA21765 (K.R.K., T.M.B., J.G.G., K.K.N., L.L.R., and M.M.H.), by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant No. K23 HD057146 (I.H.), and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (K.R.K., T.M.B., J.G.G., K.K.N., L.L.R., and M.M.H.).

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: I-Chan Huang

Financial support: I-Chan Huang, Leslie L. Robison, Melissa M. Hudson, Kevin R. Krull

Administrative support: Leslie L. Robison, Melissa M. Hudson, Kevin R. Krull

Provision of study materials or patients: Kirsten K. Ness, Jennifer Lanctot, Leslie L. Robison, Melissa M. Hudson, Kevin R. Krull

Collection and assembly of data: Tara M. Brinkman, Kirsten K. Ness, Jennifer Lanctot, Leslie L. Robison, Melissa M. Hudson, Kevin R. Krull

Data analysis and interpretation: I-Chan Huang, Tara M. Brinkman, Kelly Kenzik, James G. Gurney, Elizabeth Shenkman, Leslie L. Robison, Melissa M. Hudson, Kevin R. Krull

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2011. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipscomb J, Gotay CC, Snyder CF. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer: A review of recent research and policy initiatives. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:278–300. doi: 10.3322/CA.57.5.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finnegan L, Campbell RT, Ferrans CE, et al. Symptom cluster experience profiles in adult survivors of childhood cancers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finnegan L, Shaver JL, Zenk SN, et al. The symptom cluster experience profile frame work. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:E377–E386. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.E377-E386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meeske KA, Siegel SE, Globe DR, et al. Prevalence and correlates of fatigue in long-term survivors of childhood leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5501–5510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulrooney DA, Ness KK, Neglia JP, et al. Fatigue and sleep disturbance in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study (CCSS) Sleep. 2008;31:271–281. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbertson-White S, Aouizerat BE, Jahan T, et al. A review of the literature on multiple symptoms, their predictors, and associated outcomes in patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2011;9:81–102. doi: 10.1017/S147895151000057X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esther Kim JE, Dodd MJ, Aouizerat BE, et al. A review of the prevalence and impact of multiple symptoms in oncology patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:715–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkova J, Aktas A, Walsh D, et al. Cancer symptom clusters: Clinical and research methodology. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1149–1166. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clanton NR, Klosky JL, Li C, et al. Fatigue, vitality, sleep, and neurocognitive functioning in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer. 2011;117:2559–2568. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu Q, Krull KR, Leisenring W, et al. Pain in long-term adult survivors of childhood cancers and their siblings: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pain. 2011;152:2616–2624. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. JAMA. 2003;290:1583–1592. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeltzer LK, Recklitis C, Buchbinder D, et al. Psychological status in childhood cancer survivors: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2396–2404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM. Long-term complications following childhood and adolescent cancer: Foundations for providing risk-based health care for survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:208–236. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.4.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oeffinger KC, van Leeuwen FE, Hodgson DC. Methods to assess adverse health-related outcomes in cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:2022–2034. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharp LK, Kinahan KE, Didwania A, et al. Quality of life in adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2007;24:220–226. doi: 10.1177/1043454207303885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Nolan VG, et al. Prospective medical assessment of adults surviving childhood cancer: Study design, cohort characteristics, and feasibility of the St. Jude lifetime cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:825–836. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, et al. Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: The children's oncology group long-term follow-up guidelines from the children's oncology group late effects committee and nursing discipline. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4979–4990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, et al. The childhood cancer survivor study: A national cancer institute-supported resource for outcome and intervention research. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2308–2318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schultz KA, Ness KK, Whitton J, et al. Behavioral and social outcomes in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3649–3656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kadan-Lottick NS, Zeltzer LK, Liu Q, et al. Neurocognitive functioning in adult survivors of childhood non-central nervous system cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:881–893. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Punyko JA, Mertens AC, Gurney JG, et al. Long-term medical effects of childhood and adolescent rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44:643–653. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derogatis L. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 2000. Brief Symptom Inventory 18: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, et al. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: New representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Ward BW, et al. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National health interview survey, 2010. Vital Health Stat. 2012;10:1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, et al. It's not over when it's over: Long-term symptoms in cancer survivors–a systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2010;40:163–181. doi: 10.2190/PM.40.2.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheville AL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, et al. The value of a symptom cluster of fatigue, dyspnea, and cough in predicting clinical outcomes in lung cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang P, Cheville AL, Wampfler JA, et al. Quality of life and symptom burden among long-term lung cancer survivors. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:64–70. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182397b3e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berger AM, Farr L. The influence of daytime inactivity and nighttime restlessness on cancer-related fatigue. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999;26:1663–1671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger AM, Higginbotham P. Correlates of fatigue during and following adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy: A pilot study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000;27:1443–1448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: Occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:743–753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miaskowski C, Lee KA. Pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances in oncology outpatients receiving radiation therapy for bone metastasis: A pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17:320–332. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beck SL, Dudley WN, Barsevick AM, et al. Pain, sleep disturbance, and fatigue in patients with cancer: Using a mediation model to test a symptom cluster. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;37:E48–E55. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.E48-E55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cleeland CS, Bennett GJ, Dantzer R, et al. Are the symptoms of cancer and cancer treatment due to a shared biologic mechanism? A cytokine-immunologic model of cancer symptoms. Cancer. 2003;97:2919–2925. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee BN, Dantzer R, Langley KE, et al. A cytokine-based neuroimmunologic mechanism of cancer-related symptoms. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2004;11:279–292. doi: 10.1159/000079408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Lee K. Symptom clusters: The new frontier in symptom management research. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32:17–21. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim HJ, Barsevick AM, Fang CY, et al. Common biological pathways underlying the psychoneurological symptom cluster in cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35:E1–E20. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318233a811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barsevick AM. The elusive concept of the symptom cluster. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:971–980. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.971-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dodd MJ, Miaskowski C, Paul SM. Symptom clusters and their effect on the functional status of patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28:465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox SW, Lyon DE. Symptom clusters and quality of life in survivors of lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:931–936. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.931-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaston-Johansson F, Fall-Dickson JM, Bakos AB, et al. Fatigue, pain, and depression in pre-autotransplant breast cancer patients. Cancer Pract. 1999;7:240–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.75008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miaskowski C, Aouizerat BE, Dodd M, et al. Conceptual issues in symptom clusters research and their implications for quality-of-life assessment in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007;37:39–46. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgm003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang XS, Fairclough DL, Liao Z, et al. Longitudinal study of the relationship between chemoradiation therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer and patient symptoms. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4485–4491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ness KK, Gurney JG, Zeltzer LK, et al. The impact of limitations in physical, executive, and emotional function on health-related quality of life among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kjaer TK, Johansen C, Ibfelt E, et al. Impact of symptom burden on health related quality of life of cancer survivors in a Danish cancer rehabilitation program: A longitudinal study. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:223–232. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.530689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harding R, Clucas C, Lampe FC, et al. What factors are associated with patient self-reported health status among HIV outpatients? A multi-centre UK study of biomedical and psychosocial factors. AIDS Care. 2012;24:963–971. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.668175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sogutlu A, Levenson JL, McClish DK, et al. Somatic symptom burden in adults with sickle cell disease predicts pain, depression, anxiety, health care utilization, and quality of life: The PiSCES project. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davison SN, Jhangri GS. Impact of pain and symptom burden on the health-related quality of life of hemodialysis patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng KK, Lee DT. Effects of pain, fatigue, insomnia, and mood disturbance on functional status and quality of life of elderly patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;78:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan H, Sellick K. Symptoms, psychological distress, social support, and quality of life of Chinese patients newly diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27:389–399. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200409000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jensen MP, Kuehn CM, Amtmann D, et al. Symptom burden in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Apajasalo M, Sintonen H, Siimes MA, et al. Health-related quality of life of adults surviving malignancies in childhood. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1354–1358. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elkin TD, Phipps S, Mulhern RK, et al. Psychological functioning of adolescent and young adult survivors of pediatric malignancy. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:582–588. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199712)29:6<582::aid-mpo13>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Novakovic B, Fears TR, Horowitz ME, et al. Late effects of therapy in survivors of Ewing's sarcoma family tumors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;19:220–225. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, Caron HN, et al. Quality of life and current coping in young adult survivors of childhood cancer: Positive expectations about the further course of the disease were correlated with better quality of life. Psychooncology. 2006;15:31–43. doi: 10.1002/pon.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zeltzer LK, Chen E, Weiss R, et al. Comparison of psychologic outcome in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia versus sibling controls: A cooperative children's cancer group and national institutes of health study. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:547–556. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zeltzer LK, Lu Q, Leisenring W, et al. Psychosocial outcomes and health-related quality of life in adult childhood cancer survivors: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:435–446. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Felder-Puig R, Formann AK, Mildner A, et al. Quality of life and psychosocial adjustment of young patients after treatment of bone cancer. Cancer. 1998;83:69–75. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980701)83:1<69::aid-cncr10>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maunsell E, Pogany L, Barrera M, et al. Quality of life among long-term adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2527–2535. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moe PJ, Holen A, Glomstein A, et al. Long-term survival and quality of life in patients treated with a national all protocol 15-20 years earlier: IDM/HDM and late effects? Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;14:513–524. doi: 10.3109/08880019709030908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: Meta-analyses. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:13–34. doi: 10.2190/EUFN-RV1K-Y3TR-FK0L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kwekkeboom KL, Abbott-Anderson K, Cherwin C, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of a patient-controlled cognitive-behavioral intervention for the pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance symptom cluster in cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44:810–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.12.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.May AM, Korstjens I, van Weert E, et al. Long-term effects on cancer survivors' quality of life of physical training versus physical training combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy: Results from a randomized trial. Suppor Care Cancer. 2009;17:653–663. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0519-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wanchai A, Armer JM, Stewart BR. Nonpharmacologic supportive strategies to promote quality of life in patients experiencing cancer-related fatigue: A systematic review. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:203–214. doi: 10.1188/11.CJON.203-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rupp AA, Templin J, Henson RA. Diagnostic Measurement: Theory, Methods, and Applications. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]