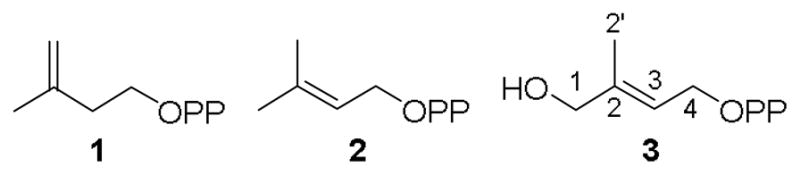

There are ~ 65,000 terpenes known.[1] These molecules are produced from two isoprenoid (C5) diphosphates: isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP, 1) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP, 2).[2] In plant plastids, IPP and DMAPP are produced primarily via the 2-C-methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway from E-1-hydroxy-2-methyl-but-2-enyl 4-diphosphate (HMBPP, 3) in a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme IspH, and this route is also used in most bacteria, as well as in malaria parasites.

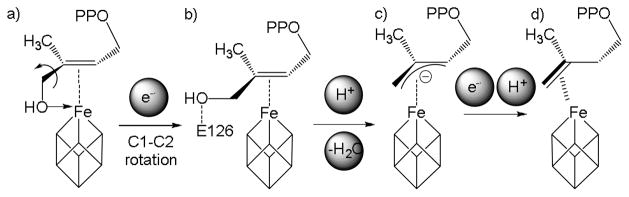

There is thus interest in understanding the mechanism of action of IspH since this could lead to new inhibitors of interest as anti-infective drug leads. IspH is a 4Fe-4S cluster-containing protein and catalyzes the deoxygenation of HMBPP via a 2H+/2e− reduction.[3] There has been considerable debate over the IspH mechanism of action with cationic, anionic, radical, butadiene as well as organometallic hypotheses being proposed.[4] Most of these proposals have now been ruled out, but there is considerable evidence in support of the organometallic hypothesis.[5] In this hypothesis, it is proposed that HMBPP initially binds to the oxidized ([Fe4S4]2+) cluster via O-1 (in the CH2OH group), Scheme 2a. On cluster reduction, the CH2OH group rotates about C1-C2 and moves away from the cluster to interact with the highly conserved E126 (E. coli residue numbering), and a diphosphate OH group, which can provide the H+ required for dehydroxylation, and subsequent ligand protonation. The intermediate that forms is stabilized by a π interaction between the alkene group and the cluster, Scheme 2b. An internal 2e− transfer then ensues, resulting in a “super-oxidized” or HiPIP (High-Potential Iron-Sulfur Protein, [Fe4S4]3+)-like S = ½ cluster and an allyl anion, Scheme 2c, which after addition of a second electron and H+ yields the IPP/DMAPP products and the original oxidized cluster, Scheme 2d.

Scheme 2.

Proposed allyl anion mechanism for IspH catalysis

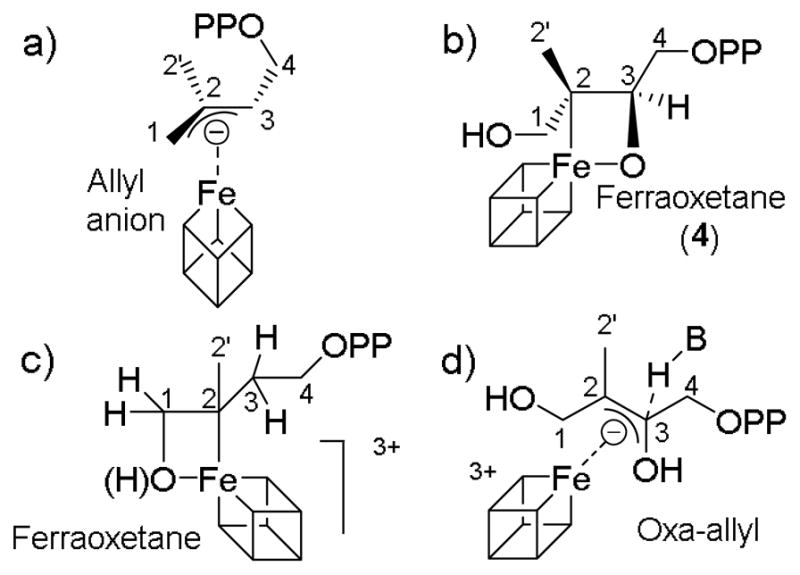

More recently, a second organometallic mechanism has been proposed[6] for IspH in which another species, a ferraoxetane, is involved. This intermediate is analogous to the ferraoxetane intermediate we previously proposed for IspG catalysis[7,8] and would contain Fe-O as well as Fe-C bonds. In addition, these workers have proposed another alternative, oxa-allyl, model for IspG catalysis.[9] In essence, then, there are two sets of models: the allyl anion model for IspH[4,5] together with the ferraoxetane model for IspG[7, 8] that we have proposed (Schemes 3a, b), and the ferraoxetane model for IspH together with the oxa-allyl model for IspG[9] (Schemes 3c, d). What is not clear from the recently proposed IspH ferraoxetane mechanism[6] (Scheme 3c) is how DMAPP could form, and how this mechanism can be reconciled with the observation that the CH2OH group rotates away from the cluster, as deduced from both crystallographic and isotope-labeling experiments.[10,11] We have thus investigated the chemical nature of the newly reported IspH reaction intermediate[6] in more detail by using HYSCORE[12] spectroscopy with 2H, 13C and 17O-labeled substrates and one-electron reduced Aquifex aeolicus IspH, which yields an intense EPR spectrum characterized by g11 = 2.17.[6]

Scheme 3.

Proposed structures of reaction intermediates involved in IspH and IspG catalysis. The structures we have proposed are a) for IspH and b) for IspG;[4,5,7,8] the structures from alternative proposals are c) for IspH and d) for IspG.[6,9]

With IspG, we previously reported the results of HYSCORE and ENDOR[13] experiments using nine 2H, 13C and 17O-labeled substrates that produced the intermediate “X”, proposed to be the ferraoxetane 4 (Scheme 3b). There were three key observations that led to this structural proposal: First, the HYSCORE spectrum of “X” prepared using an 17O-labeled substrate exhibited a large (~ 8 MHz) isotropic hyperfine interaction. This coupling is very similar to those seen with H217O bound to the unique, 4th Fe in the 4Fe-4S cluster in aconitase (8.65 MHz), and most hyperfine couplings for systems containing Fe-O bonds are in the range ~ 8–15 MHz.[14–16] Second, there was a ~ 17 MHz hyperfine coupling observed for the quaternary carbon (C2), while all other carbons had much smaller hyperfine couplings (< 4 MHz), indicating formation of a Fe-C2 bond.[7, 8] Third, the large (~ 12 MHz) 1H hyperfine coupling observed in the absence of any isotopic labeling was shown to arise from a single hydrogen in the C2′ methyl group[8] since, using a CD3 labeled substrate, we found three signals, one (Aiso (2H) = 1.7 MHz) corresponding to the Aiso (1H) ~ 12 MHz signal. These isotope-labeling experiments (and the results of DFT calculations) suggested that “X” was the ferraoxetane 4.[7]

The structure of 4 (Scheme 3b) is clearly similar to that now proposed for the g11 = 2.17 IspH reaction intermediate[6] (Scheme 3c), the exception being of course that there are differences in the positions of the H/alkyl groups (since the substrates are different). It seems implausible that these would have major effects on electronic structure, in which case two predictions for the IspH ferraoxetane model would be: 1) a large 1-17O hyperfine coupling and 2) a large 13C(2) hyperfine coupling. With the allyl anion model we proposed previously,[4,5] the predictions would be: 1) no hyperfine interaction with 17O (since it is not present), and 2) there should be 3 13C hyperfine couplings, one to each of the 3 carbons in the allyl anion.

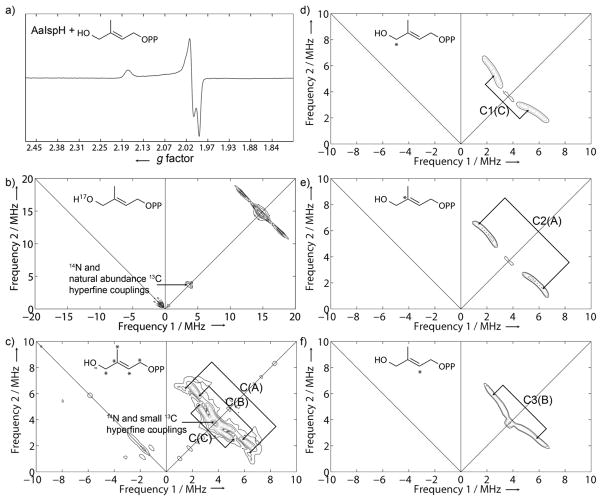

We first obtained EPR and HYSCORE spectra of reconstituted, one-electron reduced Aquifex aeolicus IspH (AaIspH) with [1-17O]-HMBPP (that is, labeled at the 1, CH2OH position), since in the recently proposed IspH ferraoxetane model this group is directly bonded to the unique 4th Fe in the 4Fe-4S cluster.[6] The EPR spectrum was essentially the same as that we reported previously for a sample prepared from E. coli IspH in the presence of excess dithionite and HMBPP, having g11 = 2.17, g22 =2.01 and g33 = 1.99, Figure 1a. The HYSCORE spectrum is shown in Figure 1b and there is no evidence for any 17O signal. These new results, therefore, do not provide support for the IspH ferraoxetane hypothesis but are consistent with formation of an allyl anion complex (in which the 17O has been lost).

Figure 1.

a) 9.05 GHz continuous-wave EPR spectrum of one-electron reduced A. aeolicus IspH + HMBPP. b) 9.68 GHz HYSCORE spectrum of one-electron reduced AaIspH + [1-17O]-HMBPP, sum of spectra with τ = 128, 182 and 236 ns, B0 = 344.4 mT. c) 9.68 GHz HYSCORE spectrum of one-electron reduced AaIspH + [U-13C5]-HMBPP, sum spectra with τ = 128, 150, 166, 182, 196 and 208 ns, B0 = 344.7 mT. d) 9.69 GHz HYSCORE spectrum of one-electron reduced AaIspH + [1-13C]-HMBPP. e) 9.69 GHz HYSCORE spectrum of one-electron reduced AaIspH + [2-13C]-HMBPP. f) 9.69 GHz HYSCORE spectrum of one-electron reduced AaIspH + [3-13C]-HMBPP. d) – f) are all sum spectra with τ = 136, 160 and 196 ns, B0 = 344.1 mT. All spectra were taken at 10 K.

Next, we used a uniformly 13C-labeled HMBPP to produce the g11 = 2.17 species. There was no evidence for a large (~ 17 MHz) 13C hyperfine coupling, Figure 1c and Figure S1. There were, however, three sets of small hyperfine couplings (denoted C(A), C(B) and C(C) in Figure 1c). To assign these resonances, we synthesized [1-13C]-, [2-13C]- and [3-13C]-HMBPPs, and obtained HYSCORE spectra of the g11 = 2.17 intermediates. The hyperfine couplings could be simulated using EasySpin[17] with Aii(A) = [2.0, 0.5, 6.7] MHz; Aii(B) = [-1.1, -0.8, 7.3] MHz and Aii(C) = [7.3, 0.9, 0.9] MHz, Figures S2 and S3, corresponding to Aiso = 3.1, 1.8 and 3.0 MHz. As can be seen in Figures 1d–f, the HYSCORE spectrum of the [1-13C]-HMBPP labelled sample corresponds to the C(C) (Aiso ~ 3.0 MHz) signal, the [2-13C] sample corresponds to C(A) (Aiso ~ 3.1 MHz) and the spectrum of the [3-13C]-HMBPP labelled sample corresponds to C(B) (Aiso ~ 1.8 MHz).

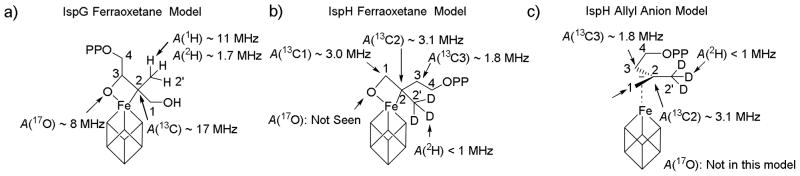

Next, we investigated the HYSCORE spectra of two 2H-labeled HMBPPs: [2′-2H3]-HMBPP and [4-2H2]-HMBPP, bound to IspH (as the g11 = 2.17 reaction intermediate). In previous work[5] we obtained HYSCORE spectra of (±)-[1-2H1]- and [3-2H]-HMBPP complexed with reduced EcIspH (the same g11 = 2.17 reaction intermediate) under turnover conditions. Both exhibited clear 2H hyperfine couplings with Aiso ~ 0.9 MHz and 0.5 MHz, respectively, for the (±)-[1-2H1]- and [3-2H]-HMBPP ligands, Figure S4a, b. The HYSCORE spectra of one-electron reduced A. aeolicus IspH samples (again, characterized by identical gii values as samples prepared by freeze-quenching) with [2′-2H3]-HMBPP and [4-2H2]-HMBPP are shown in Figures S4c, d. In both cases, 2H hyperfine couplings are present, but they are clearly very small, inconsistent with the expectation that one deuteron in the methyl group in a ferraoxetane would have a large hyperfine coupling, as seen in IspG. The hyperfine couplings seen in IspG[7,8] are shown on the ferraoxetane structure in Figure 2a; the new experimental results for IspH are shown on the IspH ferraoxetane model in Figure 2b, and the experimental results for IspH are shown again on the allyl anion model, in Figure 2c. In the IspG ferraoxetane (Figure 2a), both atoms bonded to Fe (O3, C2) have large hyperfine couplings. Similar couplings would be expected for an IspH ferroxetane but there is actually no 17O signal observed, and the C2 hyperfine coupling tensor is Aii = [2.0, 0.5, 6.7] MHz, to be compared with Aii = [14.5, 12.0, 26.5] MHz in IspG[8,9]. These results support the allyl anion π-complex model (Figure 2c) in which there is no 17O hyperfine coupling because the 17O has already been removed, as water, and there are three small 13C hyperfine couplings (to C1, C2 and C3 in an allyl anion). These 17O and 13C results are also supported by current and previous 2H HYSCORE/ENDOR spectroscopic results. With the IspG ferraoxetane (Figure 2a), there is one very large 2H/1H hyperfine coupling, due to a single proton in the CD3/CH3 group. There is no corresponding feature in the IspH reaction intermediate that would be expected from the structure shown in Figure 2b, and the couplings that are seen are larger for H1, H3 (in the allyl group) than they are for H2′ and H4. The lack of any large 2H, 13C or 17O hyperfine couplings, together with the three observed 13C HYSCORE signals, are all supportive of an allyl anion IspH intermediate[5] and not a ferraoxetane.[6]

Figure 2.

Hyperfine couplings (Aiso, MHz) observed for reaction intermediates in IspH and IspG catalysis based on HYSCORE and/or ENDOR spectra with isotopically-labeled substrates.

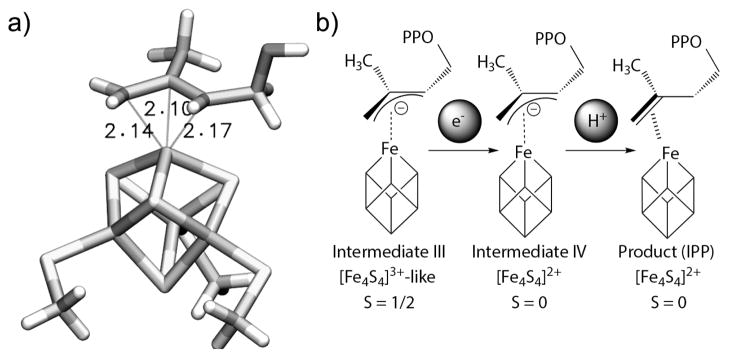

The question then arises as to whether the g11=2.17 species corresponds to the intermediate observed crystallographically.[18,19] In the latter the average distance from Fe to C1, 2 and 3 is 2.8 ± 0.3 Å. Using the hyperfine tensor results and the point dipole approximation with the spin projection coefficients for aconitase,[20] we obtained a range of 2.0 (± 0.2) to 2.5 (± 0.2) Å. To try to obtain more accurate results, we next investigated the allyl anion/Fe-S cluster structure using DFT. We used a [Fe4S4(SMe)3(η3-CH2-C(CH3)-CH(CH2OH)] cluster with S = 1/2, with methods reported previously, [21–23] using the Gaussian09 program.[24] After full geometry optimization (Figure 3a), the distances between the unique 4th Fe and C1, C2, and C3 were 2.14, 2.10 and 2.17 Å. The computed Aiso values were in quite good accord with experiment: Aiso(C1) = 3.0 MHz (expt.), 1.91 MHz (calc.); Aiso(C2) = 3.1 MHz (expt.), 2.87 MHz (calc.); Aiso (C3) = 1.8 MHz (expt.), 1.70 MHz (calc.), Table S1 and Figure S5. These results all indicate that the g11 = 2.17 species is the [Fe4S4]3+-like/allyl anion species III[5] (Figure 3b, left) while the species observed crystallographically is likely a weakly bound product that forms via IV (Figure 3b, middle), based on the ~ 2.8 Å bond lengths seen in the x-ray structure (Figure 3b, right).

Figure 3.

IspH intermediate structures and mechanism. a) The model used to compute hyperfine tensors. b) Reduction and protonation of the [Fe4S4]3+-allyl anion results in product formation with a proposed weak π–interaction between the double bond in the IPP product and the 4th Fe.

In summary: the results reported here are of interest for several reasons. First, using a [1-17O] HMBPP substrate we find no evidence for Fe-O bonding in an IspH reaction intermediate prepared by using a one-electron reduced cluster, making a ferraoxetane intermediate unlikely. Second, using a uniformly 13C-labeled HMBPP substrate, we find no evidence for the large (~17 MHz) hyperfine interaction seen previously with IspG and attributed there to a ferraoxetane intermediate. Rather, we detected three signals, all with quite small hyperfine couplings. Third, using [1-13C], [2-13C] and [3-13C]-labeled HMBPP substrates, we were able to specifically assign all three signals. Fourth, the 13C hyperfine couplings observed were in good accord with DFT predictions. Fifth, we find no evidence for the large hyperfine interaction seen previously with the IspG (ferraoxetane) reaction intermediate due to a single proton in the C2′ CH3 group. Overall, the results are of broad general interest since they help clarify the nature of the g11 = 2.17 reaction intermediate observed in IspH catalysis, highlighting the unusual, organometallic mechanism of the reaction. Moreover, the results are consistent with both crystallographic[10] and isotope-labeling[11] experiments which indicate C1-C2 bond rotation in the allyl anion model that would not occur with the ferraoxetane mechanism, plus, the allyl anion mechanism provides a route to DMAPP formation that is absent in the ferraoxetane mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

IspH products and substrate

Footnotes

This work was supported by an NIH grant to E. O. (GM065307), an NIH grant to Y. Z. (GM085774), equipment grants from NIH (S10RR023614), NSF (CHE-0840501), and the North Carolina Biotechnology Center (NCBC 2009-IDG-1015) to T. I. S., and a pre-doctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association, Midwest Affiliate (11PRE7500042) to J. L.. We thank Drs. Hassan Jomaa and Jochen Wiesner for providing the A. aeolicus IspH expression system and Mark J. Nilges for assistance with the EPR spectroscopy.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Contributor Information

Jikun Li, Center for Biophysics and Computational Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 607 South Mathews Avenue, Urbana, IL 61801 (USA).

Dr. Ke Wang, Department of Chemistry, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 600 South Mathews Avenue, Urbana, IL 61801 (USA), Fax: (+1)217-244-0997.

Dr. Tatyana I. Smirnova, Department of Chemistry, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695 (USA)

Rahul L. Khade, Department of Chemistry, Chemical Biology, and Biomedical Engineering, Stevens Institute of Technology, Castle Point on Hudson, Hoboken NJ 07030 (USA)

Prof. Dr. Yong Zhang, Department of Chemistry, Chemical Biology, and Biomedical Engineering, Stevens Institute of Technology, Castle Point on Hudson, Hoboken NJ 07030 (USA)

Prof. Dr. Eric Oldfield, Email: eoldfiel@illinois.edu, Department of Chemistry, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 600 South Mathews Avenue, Urbana, IL 61801 (USA), Fax: (+1)217-244-0997

References

- 1.Buckingham J. Dictionary of Natural Products on DVD. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oldfield E, Lin FY. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2012;51:1124–1137. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolff M, Seemann M, Tse Sum Bui B, Frapart Y, Tritsch D, Garcia Estrabot A, Rodríguez-Concepción M, Boronat A, Marquet A, Rohmer M. FEBS Lett. 2003;541:115–120. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00317-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang W, Wang K, Liu YL, No JH, Li J, Nilges MJ, Oldfield E. PNAS. 2010;107:4522–4527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W, Wang K, Span I, Jauch J, Bacher A, Groll M, Oldfield E. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:11225–11234. doi: 10.1021/ja303445z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu W, Lees NS, Hall D, Welideniya D, Hoffman BM, Duin EC. Biochemistry. 2012;51:4835–4849. doi: 10.1021/bi3001215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang W, Li J, Wang K, Huang C, Zhang Y, Oldfield E. PNAS. 2010;107:11189–11193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000264107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang W, Wang K, Li J, Nellutla S, Smirnova TI, Oldfield E. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8400–8403. doi: 10.1021/ja200763a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu W, Lees NS, Adedeji D, Wiesner J, Jomaa H, Hoffman BM, Duin EC. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14509–14520. doi: 10.1021/ja101764w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Span I, Gräwert T, Bacher A, Eisenreich W, Groll M. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2012;416:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Citron CA, Brock NL, Rabe P, Dickschat JS. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2012;51:4053–4057. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Höfer P, Grupp A, Nebenführ H, Mehring M. Chemical Physics Letters. 1986;132:279–282. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies ER. Physics Letters A. 1974;47:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy MC, Werst M, Telser J, Emptage MH, Beinert H, Hoffman BM. PNAS. 1987;84:8854–8858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werst MM, Kennedy MC, Beinert H, Hoffman BM. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10526–10532. doi: 10.1021/bi00498a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Telser J, Emptage MH, Merkle H, Kennedy MC, Beinert H, Hoffman BM. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:4840–4846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoll S, Schweiger A. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2006;178:42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gräwert T, Span I, Eisenreich W, Rohdich F, Eppinger J, Bacher A, Groll M. PNAS. 2010;107:1077–1081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913045107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gräwert T, Span I, Bacher A, Groll M. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2010;49:8802–8809. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsby CJ, Hong W, Broderick WE, Cheek J, Ortillo D, Broderick JB, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3143–3151. doi: 10.1021/ja012034s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Oldfield E. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4470–4471. doi: 10.1021/ja030664j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang K, Wang W, No JH, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Oldfield E. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6719–6727. doi: 10.1021/ja909664j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu YL, et al. PNAS. 2012;109:8558–8563. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 09 Revision B.01. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford CT: 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.