Abstract

The β93 Cysteine (β93Cys) residue of hemoglobin is conserved in vertebrates but its function in the red blood cell (RBC) remains unclear. Since this residue is present at concentrations more than two orders of magnitude higher than enzymatic components of the RBC antioxidant network, a role in the scavenging of reactive species was hypothesized. Initial studies utilizing mice that express human hemoglobin with either Cys (B93C) or Ala (B93A) at the β93 positions, demonstrated that loss of the β93Cys did not affect activities nor expression of established components of the RBC antioxidant network (catalase, superoxide dismutase, peroxiredoxin-2, glutathione peroxidase, GSH:GSSG ratios). Interestingly, exogenous addition to RBC of reactive species that are involved in vascular inflammation demonstrated a role for the β93Cys in hydrogen peroxide and chloramine consumption. To simulate oxidative stress and inflammation in vivo, mice were challenged with LPS. Notably, LPS induced a greater degree of hypotension and lung injury in B93A versus B93C mice, which was associated with greater formation of RBC reactive species and accumulation of DMPO-reactive epitopes in the lung. These data suggest that the β93Cys is an important effector within the RBC antioxidant network contributing to the modulation of tissue injury during vascular inflammation.

Keywords: Inflammation, oxidative stress, antioxidant, hemoglobin, endotoxemia, erythrocytes

Introduction

Red blood cells (RBC) are constantly exposed to reactive species formed from either hemoglobin autoxidation and / or redox cycling reactions between the heme and various oxidizing and nitrosating species including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), lipid hydroperoxides, nitric oxide (•NO), peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and hypochlorous acid (HOCl). This is illustrated by studies showing increased nitration, thiol oxidation or hemoglobin dityrosine formation in RBC from various hematologic and non-hematologic diseases [1–4]. Functionally, this can cause decreased RBC deformability and increased hemolysis, leading to ischemic stress, vascular and pulmonary inflammation and toxicity. Interestingly, in addition to damage to the RBC itself, RBC-derived reactive species have also been suggested to mediate cellular injury in tissues [5].

RBCs are endowed with a robust and complimentary network of antioxidant defenses which protect against exposure to intra- and extracellular reactive species. For example, three-independent enzymatic systems (catalase, glutathione peroxidase and peroxiredoxin-2) reduce hydrogen peroxide to water depending on the amount of H2O2 and presence of co-factors and co-reducing systems [6]. The vital importance of a functional antioxidant network in the RBC is highlighted by the severe pathological consequences that are observed when either enzymes important for the maintenance of RBC redox homeostasis are dysfunctional [7] or when alterations in hemoglobin lead to instability of the protein and increased production of reactive species [2, 8].

The potential for hemoglobin itself to exert antioxidant properties is less well understood. Interestingly, verterbrate hemoglobins can contain a number of reactive thiols [9, 10], which coupled with hemoglobin protein concentrations (~5mM in human RBC at ~40% hematocrit), exceed typical antioxidant enzymes by several orders of magnitude. This raises the possibility that hemoglobin thiols may play a role in the metabolism of RBC reactive species. Human hemoglobin has only one reactive cysteine, which is positioned at the 93rd codon of the β-chains (β93Cys). This residue is conserved amongst vertebrates but its function remains unclear. Previous studies have shown that the reactivity of the β93Cys residues towards thiol-reactive agents is allosterically controlled by oxygen-dependent changes in hemoglobin conformation with the β93Cys in the R-state being more reactive towards nitrosating and alkylating agents [11–14] and to mercurials [15, 16] than T-state hemoglobin [17]. Moreover, the β93Cys can affect electron transfer reactions and limit ferrous heme-derived superoxide production and reactivity with other RBC components [18–21]. Finally, a role for the β93Cys in the metabolism of reactive species has been implicated by the detection of β93Cys-thiyl radicals and oxidation products (mixed disulfides and cysteic acid) in this position after treatment of cell-free and intraerythrocytic hemoglobin with H2O2 [22, 23] and peroxynitrite [24]. To date, insights into the potential for the conserved β93Cys residue to affect RBC metabolism of reactive species has been limited largely to purified hemoglobin in vitro. Whether this residue can modulate oxidative stress and tissue damage during vascular inflammation in vivo is not known. To test this, we employed a mouse model expressing human hemoglobin either containing or lacking the β93Cys [25]. The data presented indicate a functional role for the β93Cys in affecting RBC metabolism of H2O2 and chloramines, which may in turn affect the severity of endotoxic shock in vivo.

Experimental

Materials

N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) was purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL) and 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine was from Acros Organics. Peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and glycine chloramine (GlyCl) were synthesized as described previously [26, 27]. Biotin hydrazide was from Thermo Fisher and AP-streptavidin from Vector Labs. Anti-Prdx2 antibody was purchased from Abcam. Ketamine and xylazine were obtained from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Pharmacy. All other reagents were of analytical grade and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co (St Louis. MO).

Animals

Hemoglobin β93Cys positive (B93C) and negative (B93A) mice were generated and maintained as previously described [25]. Age-matched males between 12 and 20 weeks of age were used. All experiments involving animals were conducted according to protocols approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham IACUC

Red Blood Cell Collection and Hemoglobin Purification

Anesthesia was induced with 5% isofluorane and maintained at 2–3% during the procedure with lack of responsiveness assessed by loss of toe-pinch reflex. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture in the presence of ACD anticoagulant solution and RBC isolated by centrifugation after washing and removal of the leukocyte layer. Hemoglobin was purified as described previously [28] and catalase removed by DEAE chromatography at pH6.7.

Hemoglobin Autoxidation

Purified, catalase-free B93C or B93A hemoglobin (40µM) was incubated at 37°C in 100mM phosphate buffer containing 100µM DTPA, pH 7.4 and visible spectra (450 – 700nm) collected every 60 minutes for 18 hours. Autoxidation was determined by measuring methemoglobin formation by spectral deconvlution as described [29].

Kinetic Analysis of Hemoglobin Reaction with Hydrogen Peroxide

Purified, catalase-free B93C or B93A hemoglobin (10–30 µM) was reacted with increasing doses of H2O2 (0–40µM) at 37°C in phosphate buffer containing 100µM of the catalase inhibitor sodium azide. Initial rates were obtained for each condition by measuring absorbance changes at 576nm during the first 10% of the reaction. Apparent first order rate constants (k’) were derived at each hemoglobin concentration by plotting initial rates versus H2O2 concentration. Second order rate constants were then obtained by plotting k’ versus hemoglobin concentration. To test ferrylhemoglobin stability, methemoglobin (20µM heme) was reacted with H2O2 (1mM) for 2 minutes before the addition of excess catalase. Decay of the resulting ferryl species was followed at 15°C by monitoring changes in absorbance at 542nm and the resulting traces fitted to a first order exponential function

Free Radical Production during Hemoglobin-Hydrogen Peroxide Reaction

Catalase-free hemoglobin (100µM heme) was incubated in the presence of 100mM DMPO in 50mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 at 37°C for 10 minutes before addition of 500µM H2O2. Aliquots were obtained at 0 (immediately before H2O2 addition), 1, 5, 10, 30 and 60 minutes after H2O2 treatment and incubated for five minutes at room temperature in the presence of 70U catalase to stop the reaction. Products were resolved by reducing SDS-PAGE followed by western blot analysis using an anti-DMPO antibody [22]. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used in order to avoid potential interference from hemoglobin peroxidase activity typical of HRP/H2O2 detection systems. A catalase-alone control was included to show no contribution from this enzyme to the resulting DMPO signal.

Saturation of RBC with Carbon Monoxide (CO)

1ml RBC suspensions (50µM heme) in isotonic phosphate buffer, (80mM sodium phosphate, 40mM NaCl, 10mM KCl, 100µM DTPA, pH 7.4) were slowly (over 2min) bubbled with CO gas (2–3ml) using a gas tight syringe. RBC were used immediately for experiments testing H2O2-dependent oxidation of Prdx2 as outlined above. In parallel, an aliquot of RBC were lysed (1:10) in air equilibrated water and visible absorbance spectrum (450–700nm) recorded for analysis of carbonmonoxide liganded ferrous hemoglobin. In all experiments, HbCO levels were >85% of total hemoglobin, with the remainder being oxyhemoglobin.

Antioxidant Assays

Reduced and oxidized glutathione were measured using a kit from Percipio Biosciences. Catalase (CAT) activity was measured in RBC lysates by following H2O2 consumption at 240 nm in the presence and absence of 5mM azide. Glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) activity was measured using tert-butylhydroperoxide as a substrate and following NADPH consumption by exogenous glutathione reductase in the presence of glutathione. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities were obtained by assessing the ability of ethanol/chloroform extracted RBC lysates to inhibit cytochrome c reduction by superoxide generated by a xanthine/xanthne oxidase system in the presence of 300µM EDTA, 20mU xanthine oxidase, 100µM xanthine and 40µM ferricytochrome c. Rates were normalized to the corresponding activity measured with a SOD standard. All enzyme assays were performed at 25°C in sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.0–7.4.

Chloramine Consumption Assays

RBC suspensions (20µM heme) from B93C and B93A mice were incubated with 20µM GlyCl at 37°C in PBS pH 7.4 under 21% or 4% oxygen in a controlled atmosphere chamber. Aliquots were removed at different times, centrifuged and the amount of remaining GlyCl in the supernatant measured by following 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine oxidation as reported [30].

Peroxiredoxin-2 and GSH Oxidation

For peroxiredoxin-2 (Prdx2) oxidation, RBC suspensions (50µM heme) were treated with H2O2, HOCl or ONOO− under either 21% or 4% oxygen at 37°C. Samples were incubated for 5, 10 and 15 minutes with ONOO−, HOCl and H2O2 respectively and then the reaction stopped by the addition of 5mM methionine. RBC were isolated and incubated with 100mM NEM for 20 minutes at 37°C. Proteins were resolved by native electrophoresis and Prdx2 analyzed by western blot using either a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody (AlexaFluor 594, Invitrogen) or an alkaline phosphatase conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody [31]. In both cases a non-specific band is observed between the Prdx2 monomer and the dimer as shown in Figure 2 consistent with previous reports [31, 32]. However, this band is present before anti Prdx-2 antibody incubation suggesting non-specific binding. No differences in the intensity of this non-specific band was observed between experimental groups. For GSH oxidation, RBC suspensions (400µM heme in isotonic sodium phosphate buffer) were incubated at 37°C with varying concentrations of either H2O2, ONOO-, HOCl or GlyCl. Time of incubation was 15min (H2O2), 10min (HOCl), 5min (ONOO−) and 10min (GlyCl). For HOCl incubations, reactions were terminated by addition of methionine (10mM). Samples were processed immediately for GSH and GSSH measurements.

Figure 2. Effects of the B93C on reactive species metabolism in RBCs.

Panel A: representative western blots from B93C or B93A RBC incubated with the indicated amounts of oxidants at 21% O2 and immunoblotting for Prdx2. Dimers and monomers were identified by respective MWt of 38KDa and 19KDa respectively. NS= non-specific band. Panel B–C: Quantification of Prdx2 oxidation in B93C (□) or B93A (■) RBC, by either H2O2 5µM, HOCl 30µM or ONOO−1 100µM) at 37°C, and at 21% O2 (B) or 4% O2 (C). Data are means ± SEM (n = 3–4), * p<0.05 as determined by t-test. Panel D and E show GlyCl consumption by RBC (20µM heme) at 21%O2 and 1%O2 respectively (pH 7.4, 37°C). Data show mean ± SEM (n=3), P<0.01 by repeated measures 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test. Panel F: Changes in GSSG after addition of H2O2, ONOO-, HOCl or GlyCl at indicated doses to RBC (400µM heme). Data are mean ± SEM (n=3–5). No significant differences were observed by 1-way ANOVA.

Measurement of Red Blood Cell Reactive Species

RBC suspensions (1×109 cells/mL) were incubated in the dark at 4°C with either 200µM DCFDA or 50µM DAF2-DA for 30 minutes. RBC were then washed, resuspended to a final 1×108 cells in 100µL in a 96-well plate, incubated in the dark for 30 minutes and fluorescence measured using a plate reader. Loading control studies were performed with each experiment by addition of saturating H2O2 concentrations to establish maximal dye fluorescence. No change in dye loading between different conditions was observed.

Measurement of Red Blood Cell Carbonyls

RBC were lysed in 10mM Tris pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 50µM DTPA, 1x protein inhibitor cocktail. 50–60µg total protein in 10mM phosphate buffer was reacted with biotin hydrazide (4mM) for 1 hour at 37°C followed by dilution 1:4 with 4x sample buffer (200mM Tris, pH 6.8; 8% SDS; 0.4% bromophenol blue; 40% glycerol; 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol). Samples were boiled prior to resolution by SDS-PAGE and subsequent transfer to nitrocellulose. Membranes were blocked with 0.1% BSA in TBS+0.1% Tween-20 and carbonyl epitopes detected by immunoblotting with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin 1:500. Blots were developed using Duo-Lux substrate from Lumigen.

Detection of Tissue Nitrone Adducts

Mice received an intraperitoneal injection of either 6.75×104 U g−1 LPS or sterile saline followed by ip injections of 1 g kg−1 DMPO dissolved in sterile saline 4 and 5 hours post LPS. Mice were sacrificed 6 hours post LPS and lungs homogenized in phosphate buffer containing 50 µM DTPA. DMPO-nitrone adducts were measured by dot blots using 40µg protein. Blots were incubated for 1h at room temperature with chicken anti-DMPO antibody (1:1000) and probed with goat anti-chicken AP-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen). The primary antibody was a generous gift from Ronald Mason and Marilyn Ehrenshaft, NIEHS/NIH.

Nitrone Adduct and Cross-linked Hemoglobin Formation

Catalase-free B93C or B93A hemoglobin (10µM) was incubated with H2O2 (100µM) in the absence or presence of DMPO (100mM) for 0–60min in isotonic phosphate buffer at 37° C. At the indicated times, samples were cooled on ice and mixed with 4x Laemli buffer +/− β mercaptoethanol. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE gel and protein stained using silver nitrate.

RBC Total Thiol Determination

RBC (1% Hct in PBS) were incubated with biotinylated NEM (2 mM) for 5 minutes before stopping by addition of 1:1 lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 2% SDS, pH 6.8 with 4mM β-mercaptoethanol). Reactive thiols were determined by western blot using streptavidin-linked alkaline phosphatase and analyzed by whole lane densitometry followed by comparison to biotinylated cytochrome c standards as previously described [33].

RBC BIAM labeling

RBC suspensions (20µM heme in isotonic phosphate buffer) were incubated at 37°C with varying concentrations of GlyCl for 10min. RBC were immediately washed and resuspended in Tris buffer (pH 8.5) containing Triton X-100 (1%) + protease inhibitor cocktail. BIAM was then added (100µM final) for 15min in the dark at 20–25°C. β-mercaptoehtanol was added to stop BIAM labeling. Lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and BIAM-labeling detected using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavadin (Vector Labs). Loading control was performed by immunoblotting against rabbit anti-human hemoglobin α (Abcam).

Nitrite and Nitrate Measurements

Plasma from B93C and B93A mice treated with either saline or 3×104 U g−1 intraperitoneal LPS was deproteinated by 1:1 addition of cold methanol and nitrite and nitrate concentrations measured simultaneously using an ENO-20 HPLC system.

Bronchoalveolar Lavages and Assessment of Acute Lung Injury

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 6.75×104 U g−1 LPS or saline and anesthetized 12 hours later by ip injection of 100mg/kg ketamine and 15 mg/kg xylazine. Once unresponsive, the trachea was exposed and a trimmed 18-gauge intravenous catheter was inserted caudally into the lumen and bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL) performed flushing twice with a total of 2 mL sterile saline. Protein in the lavage supernatant was determined using the BCA assay (Pierce). Mice were euthanized by cardiac exsanguination.

Mean Arterial Pressure Monitoring

Mice were anesthetized with 10mg/kg xylazine and 100mg/kg ketamine and the left femoral artery was catheterized with 0.05 mm tapered PE tubing. Mean arterial pressure and heart rate were recorded in awake, unrestrained mice by connecting the implanted tubing to a pressure transducer as described previously [34].

Results

B93C to B93A substitution increases hemoglobin autoxidation and protein oxidation in RBCs but has no effect on other antioxidant systems

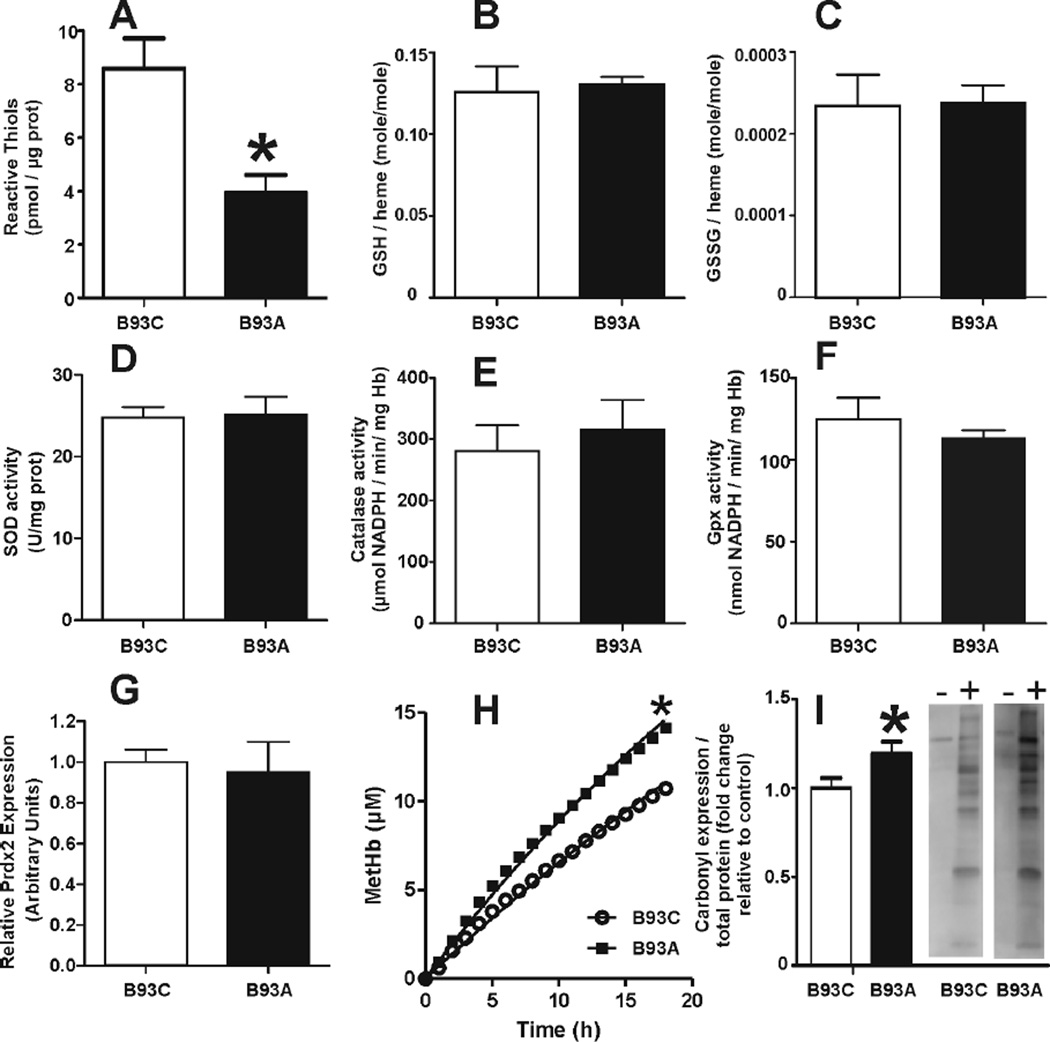

Figure 1A shows that substitution of the β93Cys with alanine led to a 50% decrease in the concentration of NEM-reactive thiols consistent with the β93Cys residue being the most abundant protein thiol in the RBC. No differences were observed in the activity of SOD, CAT and GPx, or in the levels of GSH, GSSG, and Prdx2 which suggests that mutation of the β93Cys does not affect the expression or activity of well-characterized antioxidant mechanisms in RBC. Interestingly, Figure 1H shows that hemoglobin lacking the β93Cys exhibits higher rates of autoxidation, consistent with previous observations pointing at a role for this residue in the modulation of heme reactivity [18]. Furthermore, B93A RBCs had a small but significant increase in protein carbonyls (Fig 1I), suggesting that β93Cys mutation leads to increased oxidative stress under basal conditions.

Figure 1. Effects of the B93C on the RBC antioxidant network and basal oxidative damage.

Total NEM-reactive thiols (Panel A), GSH (Panel B), GSSG (Panel C), SOD activity (Panel D), CAT activity (Panel E), Gpx activity (Panel F) and Prdx2 expression normalized to B93C levels (Panel G) were determined as described in methods. Values show mean ± SEM (n=3–4). *P<0.03 by t-test. Panel H: Kinetics of hemoglobin (40µM) autoxidation, with k = 0.014 h−1 and 0.022 h−1 for B93C and B93A respectively. *p<0.001 by 2-way ANOVA. Panel I: RBC carbonyls (normalized to protein and expressed as fold change relative to B93C). Values show mean ± SEM (n=11). *P<0.05 by t-test. Representative images taken from the same gel (−) and (+) biotin hydrazide

Effects of the β93Cys on RBC metabolism of reactive species

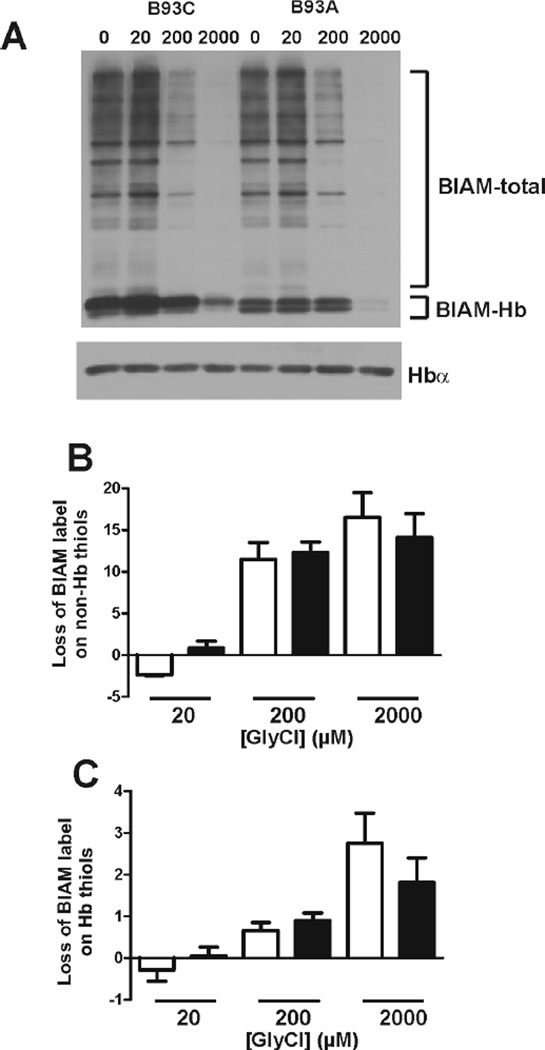

The increased protein carbonyl levels detected in B93A RBCs suggests that these cells might be less proficient at detoxifying reactive species than their B93C counterparts. To test this, candidate reactive species produced during inflammation such as H2O2, HOCl or ONOO− were added to RBC and Prdx2 oxidation assessed. Prdx2 reacts with the selected oxidants with rate constants ranging from 106 to 108 M−1s−1 which, coupled with its relatively slow recycling by thioredoxin reductase-1 in the RBC [31, 32, 35], makes Prdx2 oxidation a very sensitive index of intracellular oxidation by these species. As a result, any difference in Prdx2 oxidation between B93C and B93A RBC upon incubation with different reactive species would be suggestive of a role of the β93Cys in their metabolism. Figure 2A shows representative Prdx-2 western blots at varying doses of each oxidant. For the sakes of clarity, Fig 2B shows quantitation of changes in percent Prxd2 oxidation at a single indicated dose of H2O2, HOCl or ONOO−. Figure 2A–B shows that B93A RBCs are more susceptible to oxidation by H2O2 under oxygenated conditions (21% O2). This effect of the β93Cys on H2O2 dependent Prdx2 oxidation was lost at 4% O2 (Fig 2C), consistent with reports demonstrating that the reactivity of β93Cys is decreased under low fractional saturations [11, 13]. No differences in Prdx2 oxidation by HOCl or ONOO were observed. Interestingly, Figure 2D shows that substitution of the β93Cys leads to decreased rates of glycine chloramine consumption, consistent with the selective reactivity of chloramines with thiols and suggesting a potential role for the β93Cys residue in chloramine scavenging by RBC. Notably, this difference was again lost at lower pO2 (Fig 2E). However, Figure 2F shows that there was no difference in H2O2-, ONOO−-, HOCl- or GlyCl-dependent formation of GSSG in B93C or B93A RBC, suggesting that the reactivity of the β93Cys is not be related to the GSH/GSSG redox couple Figure 3 shows the effects of GlyCl treatment of RBC on non-hemoglobin and hemoglobin reduced thiol levels (measured by BIAM labeling). Fig 3A shows a representative gel and Fig 3B–C shows loss of non-hemoglobin and hemoglobin thiols as a function of increasing GlyCl doses. BIAM labeling was decreased by ~50% (not shown, see Fig 3A) in B93A hemoglobin versus B93C. A priori a complete loss of BIAM binding to B93A is expected due to the B93C being the only exposed reactive thiol in human hemoglobin. However, four other cysteines are present (at positions β113 and α105) which are normally relatively unreactive. Since BIAM labeling was performed in the presence of detergent, it is likely that the BIAM-signal on B93A hemoglobin observed in Fig 3A reflects reaction with these other non β93Cys thiols. Figure 3B–C show that GlyCl caused a dose dependent loss of thiols on both hemoglobin and non-hemoglobin fractions in both B93C and B93A RBC. No differences in thiol loss between B93C and B93A RBC was observed.

Figure 3. Effects of GlyCl on reduced thiol content in B93C and B93A RBC.

RBC suspensions (20µM heme) were incubated with GlyCl for 10min, 37°C and reduced thiols measured by BIAM labeling as described in methods. Panel A shows a representative blot for BIAM labeling. Immunoblotting with anti-Hbα was used as loading control. Total lane densitometry was performed and BIAM signal (normalized to Hb protein) associated with hemoglobin or non-hemoglobion bands (denoted as BIAM-total) determined. Panel B and C show respectively the GlyCl-dependent changes in BIAM-total or BIAM-Hb label compared to control (i.e. no GlyCl) signal for B93C (□) and B93A (■) RBC. Data are mean ± SEM (n=3). P = NS by 2-way RM-ANOVA for comparison between B93C and B93A.

β93Cys regulates redox reactions between cell-free hemoglobin and H2O2

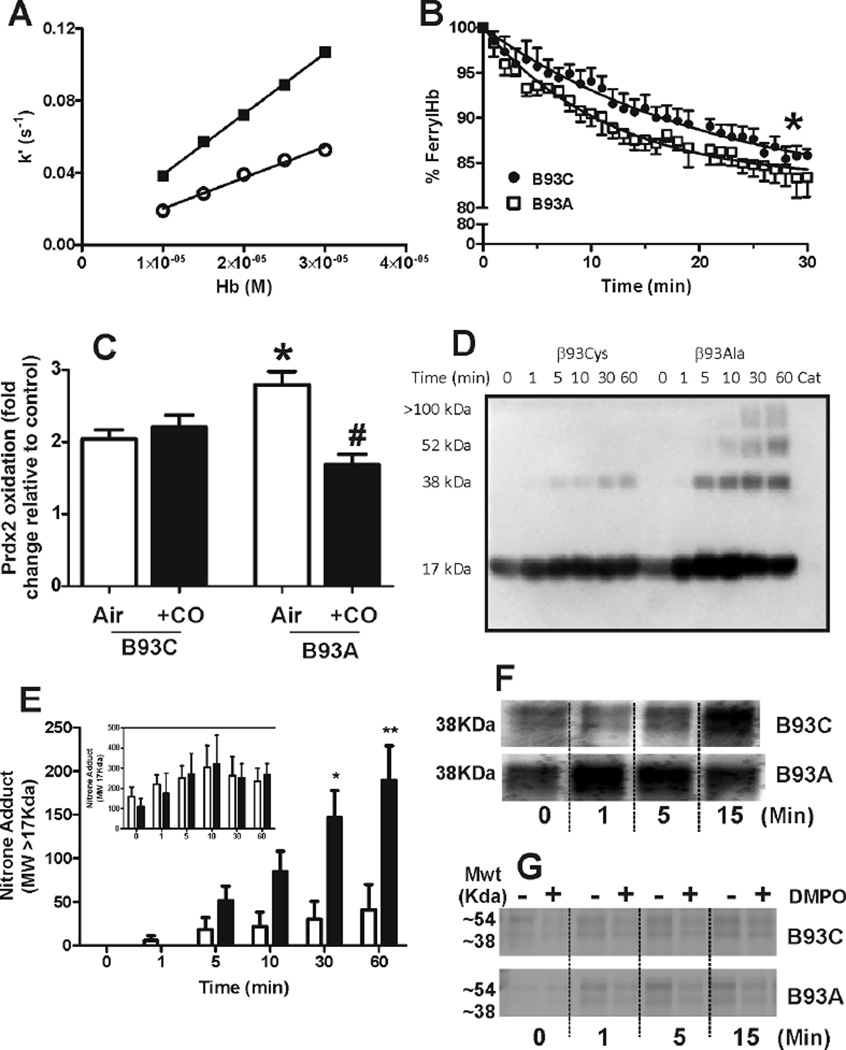

The observation that H2O2 leads to a higher degree of Prdx2 oxidation in B93A cells was surprising considering that RBCs are endowed with several systems for H2O2 scavenging. This result suggests that hemoglobin plays a role in RBC metabolism of H2O2 in a β93Cys-regulated manner. To investigate this role further, the kinetics of the reaction between H2O2 and cell-free B93C or B93A hemoglobin were determined. Figure 4A shows apparent-first order rate constants for H2O2-dependent oxyhemoglobin oxidation plotted as a function of hemoglobin concentration. The gradient indicates rate constants of approximately 1.7×103 M−1s−1 and 3.4×103 M−1s−1 for B93C and B93A hemoglobins respectively, demonstrating that the β93Cys residue slows down H2O2-dependent oxidation of oxyferrous heme by ~two-fold. H2O2-dependent hemoglobin oxidation results in formation of ferryl Hb which then enters a redox cycle with ferric heme analogous to peroxidase catalysts. Figure 4B shows that ferrylHb decay, was faster in B93A hemoglobin with first order rate constants of 2.2 ± 0.63 s−1 for B93C and 4.2 ± 0.22s−1 for B93A RBC (mean ± SEM, n=3–4). To test if altered heme reactivity modulated H2O2 metabolism in RBC, H2O2 was added to air- or CO equilibrated B93C and B93A RBC and Prdx-2 oxidation determined. Figure 4C shows that addition of H2O2 increased Prdx2 oxidation in both oxygenated B93C and B93A RBC, with the magnitude of oxidation being ~30–40% higher in the latter (consistent with data shown in Fig 2A). CO-pretreatment had no effect on H2O2 dependent Prdx2 oxidation in B93C RBC, but significantly attenuated this response in B93A RBC. suggesting that the increased yield of oxidized Prdx2 observed upon treatment of B93A with H2O2 might be a consequence of the generation higher levels of heme-derived reactive species presumably from ferryl-hemoglobin and associated protein radicals. Consistent with this hypothesis, reaction of B93A Hb with H2O2 leads to a greater increase in nitrone-adduct formation on higher MWt species corresponding to hemoglobin dimers and trimers, compared to B93C (Fig 4D–E). Moreover, formation of higher molecular weight species arising from radical-radical hemoglobin crosslinking were also observed to be more prominent with B93A hemoglobin upon total protein staining (Fig 4F). Consistent with previous studies, DMPO inhibited the formation of these higher MWt cross-linked proteins both under reducing and nonreducing conditions (Fig 4E and data not shown).

Figure 4. Effects of the B93C on hemoglobin reactions with H2O2.

Panel A shows apparent first order rate constants for H2O2 oxidation of B93C (○) and B93A (■) oxyhemoglobin plotted as a function of hemoglobin concentration. Second order rate constants determined by linear regression are 1716 ±109M−1s−1 and 3366 ±70M−1s−1 for B93C and B93A respectively (r2= 0.99; P < 0.0001). Panel B shows ferryl hemoglobin decay curves (after addition of 1mM H2O2 to 20µM metHb) measured at 542 nm at 15°C in phosphate buffer pH 7. Data show mean ± SEM (n=3–4). Lines represent exponential fits. *P < 0.01 by comparison of fit analysis. Panel C shows fold increase in Prdx2 oxidation caused by addition of H2O2 (5µM, 10min, 37°C) to either air or CO-equilibrated B93C or B93A RBC (50µM heme). Data are mean ± SEM (n=3–7). *P<0.05 relative to B93C air, #P<0.01 relative to B93A air by 1-way ANOVA with Tukey post test. Panels D and E show a representative western blot and quantitative analysis showing time dependent increases in DMPO-Hb adduct formation. No difference was observed between B93C and B93A in the formation of ~17KDa adducts (inset to panel E). Main Panel C shows changes in >17KDa adducts. Incubation of catalase with H2O2 in the absence of hemoglobin led to no detectable DMPO-adducts (Cat = catalase addition without Hb). Data are mean ± SEM, n= 4. *P<0.01 and **P<0.0001 by 2-way RM ANOVA with Bonferroni post test. Panels F and G show representative protein staining (by silver staining) of SDS-PAGE resolved samples under reducing conditions for catalase-free B93C or B93A oxyhemoglobin (10µM) treated with H2O2 (100µM) for the times indicated at 37°C, pH7.4. For panel F, images are from the same gel cropped and aligned to allow time-dependent comparison. For panel G representative images from 2 separate gels are shown and demonstrate the effects of DMPO (100mM) in protein crosslink formation.

Endotoxemia induces higher levels of oxidative stress in B93A mice

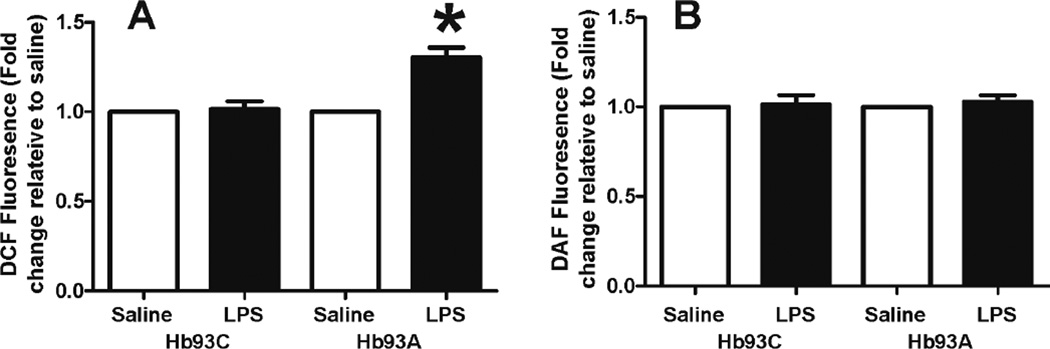

To determine whether mutation the β93Cys can affect RBC metabolism of reactive species generated during vascular inflammation, B93C or B93A mice were administered LPS, and after 12 hours RBC were isolated and loaded with the cell-permeable dyes DCF-DA and DAF2-DA. DCF-DA is sensitive to a variety of oxidative mediators and is also dependent on the presence of free iron[36], whereas, DAF2 reflects increased levels of nitrosating species [37]. Figure 5 demonstrates that RBC isolated from LPS-exposed B93A mice exhibited no changes in DAF2 fluorescence; however, B93A RBC from LPS treated mice showed significantly increased DCF fluorescence.

Figure 5. LPS induces the formation of reactive species in RBC from B93A but not B93C mice.

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with either saline or LPS 12 hours before sacrifice. RBCs were isolated, loaded with DCF-DA (Panel A) or DAF2-DA (Panel B) and incubated for 30 min at 21% O2 in PBS, at 37°C. Data are mean ± SEM (RBC from 4–5 individual mice) and are presented as fold change relative to respective saline controls. * p <0.01 by 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test.

Intraperitoneal LPS injection induces greater lung injury and worse hypotensive profile in B93A mice

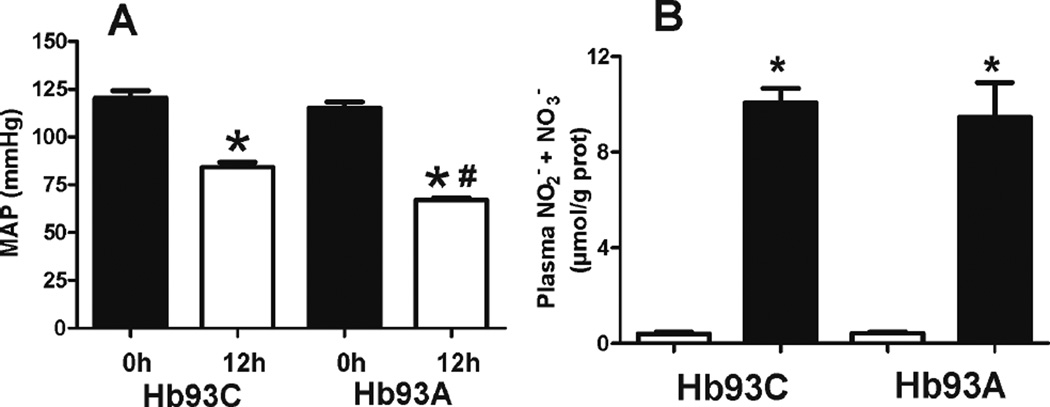

To determine whether alterations in the metabolism of reactive species by B93A RBC could affect LPS-induced injury, we first measured endotoxemia-dependent changes in mean arterial pressure (MAP). Figure 6A shows that LPS decreased MAP in both mice, but to a significantly greater extent (by 15–20mmHg) in B93A mice. No differences in pre-LPS MAP were observed, which is consistent with our previous data [25]. Since LPS induced hypotension is mediated by activation of the inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [38], total plasma nitrite plus nitrate was measured. Figure 6B shows no difference between these metabolites in B93C and the B93A mice suggesting a similar degree of iNOS induction by LPS.

Figure 6. LPS induced hypotension is more severe in B93A versus B93C mice.

(A) MAP was measured in B93C and B93A mice pre-LPS (0h) and 12h post ip LPS. Data show mean ± SEM (n=5–7) *p < 0.001 relative to respective 0h time and #p < 0.01 relative to B93C + LPS 12h by 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test. (B) Plasma nitrite + nitrate were measured 12 hours after saline (□) or LPS (■). Data show mean ± SEM (n=4–6). *p < 0.0001 versus corresponding saline control by 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post test.

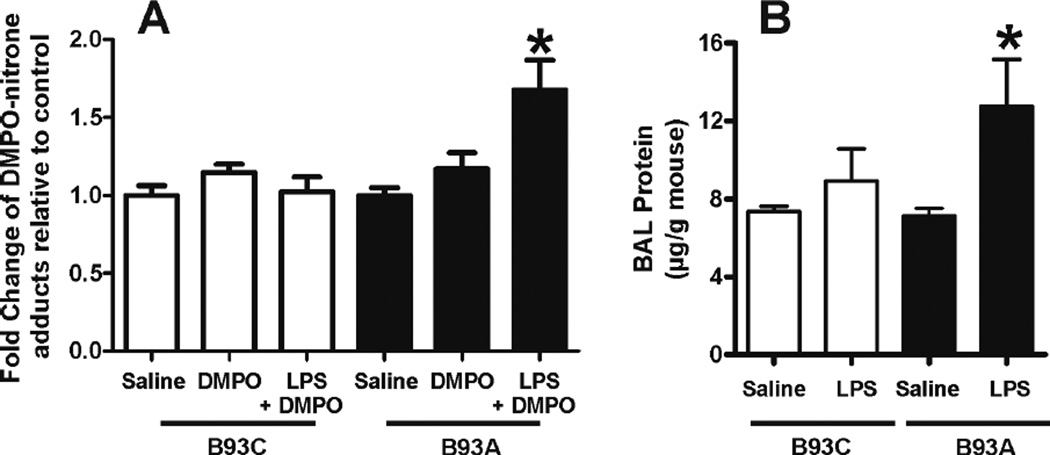

Besides the canonical hypotensive response exemplified by the data shown in Figure 6, the development of acute lung injury is a common complication in endotoxemia and systemic inflammatory syndrome. Previous studies have demonstrated that RBC-derived reactive species can cause oxidative injury in the lungs during hypoxia [5] supporting the concept that changes in RBC metabolism of reactive species may transmit oxidative damage to perfused organs. Using immuno-detection of DMPO-reactive epitopes as an index of oxidative damage, Figure 7 demonstrates that LPS increases oxidative damage in the lungs in B93A mice, but not B93C mice. Notably, these results correlate with increased pulmonary endothelial / epithelial cell damage in B93A mice as implied by a significant increase in BAL protein levels (Fig 7B).

Figure 7. LPS causes increased lung injury in B93A than in B93C mice.

(A) Mice were injected with saline or 3×104 U/g LPS and lungs collected 6hs later. 1 and 2 hr prior to sacrifice, DMPO or saline was administered as described in methods. Data show fold change in DMPOadducts relative to respective saline groups and are mean ± SEM (n = 4). *p < 0.05 relative to either saline or DMPO groups, by 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test. (B) Bronchoalveolar lavages obtained 12h post LPS treatment show worse lung injury in B93A vs. B93C as determined by protein levels in BAL. Data are mean ± SEM (n =11–17) p< 0.05 versus saline control determined by 1- way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post test.

Discussion

The role of B93C in RBC physiology has been studied for over 50 years. The high degree of B93C conservation in vertebrates [9], combined with its allosterically-controlled reactivity [13, 17] and high intracellular concentration suggest a prominent functional role in vivo. In the present work, we tested whether the β93Cys residue plays a role within the RBC antioxidant network. Most experiments linking B93C to metabolism of reactive species by RBC have been performed in vitro using either purified hemoglobin or isolated RBCs. Interestingly, phylogenetic analysis indicates that the conserved β93cys evolved in RBC as vertebrates made the transition from aquatic to terrestrial life [39], which may be associated with increased exposure to oxidizing species. Moreover, several studies have demonstrated that β93Cys becomes oxidized in vivo during pathological conditions [40–42]. Using transgenic mice expressing only human hemoglobin either in its native conformation or bearing a cysteine to alanine substitution in the β93rd position [25], allowed testing of the role of β93Cys within the context of an inflammatory tissue injury in vivo.

Initial studies were designed to validate the model system and showed that the total RBC reactive thiol pool was decreased by ~50% in B93A RBC, with no compensatory increases in the activity or expression of other RBC antioxidants (Fig 1). A role for β93Cys in controlling redox tone under basal conditions was suggested by a small but significant increase in carbonyl epitopes in cells isolated from B93A mice. We note that no differences in hemolysis nor hemolytic disorders were observed in our previous [25] or current studies (not shown). This should be contrasted with dramatic hemolytic effects that are observed in mice deficient in SOD or Prdx2 [43, 44] suggesting that basally the β93Cys residue may play a minor role in affecting oxidative damage in the RBC.

Using Prdx2 or glutathione oxidation as read-outs allowed evaluation of RBC responses to lower levels of reactive species. Results from these experiments showed that reactions with hypochlorous acid or peroxynitrite were unaffected by the β93Cys. In the case of peroxynitrite, this observation is consistent with previous data suggesting that the main targets for this oxidant in RBC are the heme centers of hemoglobin and thiols in Prdx2 [35, 45]. Similarly, whereas hypochlorous acid does react rapidly with most thiols, this reactivity is not selective, with similar high rates of reactions towards other biomolecules reported [46]. Notably, we observed that addition of H2O2 to RBC lacking the B93C led to increased oxidation of Prdx2, suggesting that this residue is directly or indirectly involved in reactions with this oxidant. We note that no differences were observed using glutathione oxidation as an index, possibly reflecting either greater sensitivity of detecting changes in Prdx2 oxidation or reflecting a differential susceptibility of the mechanisms by which H2O2 oxidizes Prdx2 and GSH to the presence of β93Cys. Indeed the lack of changes in GSH oxidation is consistent with the absence of differences in basal GPx activity.

The fact that RBC are endowed with three catalytic systems for the decomposition of H2O2 [6] makes it difficult to rationalize a role for a direct reaction between H2O2 and the heme centers. However, we observe that B93A hemoglobin has higher reactivity towards H2O2 (Fig 4); and CO-pretreatment abrogates the increased yield of Prdx2 oxidation upon H2O2 treatment in B93A cells. Collectively, these observations suggest that altered ferrous heme reactivity is related to the increase in H2O2-dependent Prdx-2 oxidation in B93A compared to B93C RBC. Clearly, the mechanism by which a two-fold acceleration of heme reactions with H2O2 leads to greater Prdx2 oxidation remains unclear. One possible explanation may be related to higher yields of oxidizing species in B93A versus B93C hemoglobin. Interestingly, ferrylHb decay, a result of electron transfer reactions with hemoglobin amino acids, was faster in the absence of the β93Cys which might lead to the formation of secondary radical species. These results are in line with previous work showing that β93Cys oxidation is quantitatively the main modification observed upon hemoglobin reaction with H2O2, with other β-chain amino acids becoming oxidized once the β93Cys is depleted [47]. Consistent with this notion, H2O2 dependent DMPO-adduct formation was greater on higher MWt -presumably cross-linked- B93A hemoglobin, suggesting a protective role for the β93Cys in decreasing DMPO-reactive radical species. The higher MWt species likely correspond to hemoglobin dimers and trimers in which DMPO could be adducting to either αTyr24, αTyr42, βTyr145 or αHis20 as previously indicated [47–50]. The fact that the formation of these high MWt species is more prominent in B93A hemoglobin and that this process is inhibitable by DMPO, further reinforces the idea that free radicals are involved in this latter process [48, 49].

Overall, these results are consistent with previous studies that demonstrate a role for B93C in decreasing production and release of superoxide in hemoglobin beta chains during hemoglobin autoxidation; in this case the product is a β93 cysteinyl radical [18]. This same radical is also detected upon treatment of cell-free hemoglobin with hydrogen peroxide [22] suggesting that the B93C might provide a route for safely transferring unpaired electrons generated in the heme pocket to other antioxidant systems in the RBC [21]. In many cases, the formation of the thiyl radical is preceded by the detection of tyrosyl radicals (Tyr42/Tyr24), and moreover it has been shown that blocking these residues prevents the formation of the cysteinyl radical [22, 51, 52]. These results also lead to speculation that increased Prdx-2 oxidation in B93A RBC could be causally related to either diminished β93 cysteinyl radical or higher hemoglobin tyrosyl / histidyl radical, a possibility that remains to be investigated

Chloramines are diffusible products generated by the reaction of hypochlorous acid with free amines and have been shown to react preferentially with thiols [53]. Moreover, chloramines are more stable than HOCl fuelling recent interest in these compounds as HOCl-derived biological mediators of oxidative damage [46]. GlyCl reactions with B93C or B93A RBC were assessed by measuring chloramine consumption, GSH oxidation and RBC thiol modification. Whereas GSH oxidation did not reveal any effect of the β93cys residue, a significant, albeit modest difference was observed when measuring rates of GlyCl consumption (Fig2D–E). Notably, no differences were observed in GlyCl-dependent thiol oxidation (Fig 3), suggesting that the slight decrease in the rate of GlyCl consumption observed in B93A RBC has no effect in the final thiol oxidation yield. Clearly, even when this data might suggest that RBC lacking the β93Cys are less proficient at scavenging vascular chloramines during inflammation, the small difference observed between GlyCl consumption rates is suggestive at best of a very minor physiological effect.

Once we established a potential role for the β93Cys in the metabolism of reactive species by RBC we decided to study whether mutation of the β93Cys had any detectable physiological consequences during vascular inflammation and oxidative stress. LPS injection is a commonly used model that mimics various aspects of sepsis, including vascular inflammation, oxidative stress, acute lung injury and results in changes to RBC function [1, 54–56]. Interestingly, RBC isolated from LPS-treated B93A mice had increased DCF, but not DAF fluorescence. We note that for these studies RBC were labeled ex vivo after washing, which suggests that either the species responsible for the oxidation of DCF is relatively stable or that LPS treatment induced modifications in the production of reactive species from RBC. In this regard, our results may indicate an increase in free or heme iron dependent oxidative stress consistent with the proposal that the β93Cys limits redox cycling secondary to formation of higher heme oxidation states and potentially prevents heme breakdown and iron release [57]. We note however that we cannot exclude a potential role for direct reactions between the β93cys and DCF radical which would manifest as an increase in DCF derived signals in B93A RBC. The fact that no effect of LPS injection was seen on DAF2 fluorescence despite the reported increase in S-nitrosothiols during endotoxemia [56, 58] suggests that mediators that lead to S-nitrosation are either exogenous to the RBC or lost during RBC isolation. Interestingly, the observation of higher DCF fluorescence in B93A RBCs correlated with a greater hypotensive response, increased levels of protein DMPO-adducts in the lungs and increased lung injury. Whether these latter observations are due to increased exposure of the lung to RBC-derived oxidants or decreased ability of these cells to scavenge inflammation-derived vascular reactive species in β93Cys-deficient animals is not clear. Similarly, how altered reactive species metabolism by the RBC lacking the β93Cys affects endotoxemia-dependent hypotension is unknown and is the focus on ongoing studies.

A considerable number of reports in the literature suggest an important role for RBC as sinks for reactive species in models of oxidative stress such as hyperoxic challenge [59], co-incubation with neutrophils [60, 61] or exogenous additions of H2O2 [62] and reactive chlorine species [63]. Most of these reports ascribe the protective role of red blood cells to the activity of catalase and superoxide dismutase as well as to the presence of a high concentration of reduced thiols. We extend this paradigm to include a modulatory role for the β93Cys residue as an allostericallycontrolled antioxidant both within the context of oxidative injury to the RBC itself as well as within the setting of vascular and pulmonary inflammation.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL092624 to RPP), P30NS057098 to JMW), and the American Heart Association (0815248E to DAV).

Footnotes

The authors declare no financial conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Condon MR, Kim JE, Deitch EA, Machiedo GW, Spolarics Z. Appearance of an erythrocyte population with decreased deformability and hemoglobin content following sepsis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H2177–H2184. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01069.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fibach E, Rachmilewitz E. The role of oxidative stress in hemolytic anemia. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8:609–619. doi: 10.2174/156652408786241384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagy E, Eaton JW, Jeney V, Soares MP, Varga Z, Galajda Z, Szentmiklosi J, Mehes G, Csonka T, Smith A, Vercellotti GM, Balla G, Balla J. Red cells, hemoglobin, heme, iron, and atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1347–1353. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.206433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spolarics Z, Condon MR, Siddiqi M, Machiedo GW, Deitch EA. Red blood cell dysfunction in septic glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H2118–H2126. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01085.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiefmann R, Rifkind JM, Nagababu E, Bhattacharya J. Red blood cells induce hypoxic lung inflammation. Blood. 2008;111:5205–5214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson RM, Ho YS, Yu DY, Kuypers FA, Ravindranath Y, Goyette GW. The effects of disruption of genes for peroxiredoxin-2, glutathione peroxidase-1, and catalase on erythrocyte oxidative metabolism. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobasch G, Rapoport SM. Hemolytic anemias due to erythrocyte enzyme deficiencies. Mol Aspects Med. 1996;17:143–170. doi: 10.1016/0098-2997(96)88345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho C-S, Lee S, Lee GT, Woo HA, Choi E-J, Rhee SG. Irreversible Inactivation of Glutathione Peroxidase 1 and Reversible Inactivation of Peroxiredoxin II by H2O2 in Red Blood Cells. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2010;12:1235–1246. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reischl E, Dafre AL, Franco JL, Wilhelm Filho D. Distribution, adaptation and physiological meaning of thiols from vertebrate hemoglobins. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007;146:22–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Storz JF, Weber RE, Fago A. Oxygenation properties and oxidation rates of mouse hemoglobins that differ in reactive cysteine content. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2012;161:265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benesch RE, Benesch R. The influence of oxygenation on the reactivity of the--SH groups of hemoglobin. Biochemistry. 1962;1:735–738. doi: 10.1021/bi00911a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guidotti G. The rates of reaction of the sulfhydryl groups of human hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:3924–3927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riggs A. The binding of N-ethylmaleimide by human hemoglobin and its effect upon the oxygen equilibrium. J Biol Chem. 1961;236:1948–1954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi R, Lusini L, Giannerini F, Giustarini D, Lungarella G, Di Simplicio P. A method to study kinetics of transnitrosation with nitrosoglutathione: reactions with hemoglobin and other thiols. Anal Biochem. 1997;254:215–220. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antonini E, Brunori M. On the Rate of a Conformation Change Associated with Ligand Binding in Hemoglobin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1969;244:3909–3912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geraci G, Parkhurst LJ. Effects of heme-globin and chain-chain interactions on the conformation of human hemoglobin. A kinetic study. Biochemistry. 1973;12:3414–3418. doi: 10.1021/bi00742a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morell SA, Hoffman P, Ayers VE, Taketa F. Reversible changes in the NEM-reactive--SH groups of hemoglobin on oxygenation-deoxygenation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1962;48:1057–1061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.48.6.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balagopalakrishna C, Abugo OO, Horsky J, Manoharan PT, Nagababu E, Rifkind JM. Superoxide produced in the heme pocket of the beta-chain of hemoglobin reacts with the beta-93 cysteine to produce a thiyl radical. Biochemistry. 1998;37:13194–13202. doi: 10.1021/bi980941c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonaventura C, Godette G, Tesh S, Holm DE, Bonaventura J, Crumbliss AL, Pearce LL, Peterson J. Internal electron transfer between hemes and Cu(II) bound at cysteine beta93 promotes methemoglobin reduction by carbon monoxide. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5499–5507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rifkind JM. Copper and the autoxidation of hemoglobin. Biochemistry. 1974;13:2475–2481. doi: 10.1021/bi00709a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winterbourn CC, Carrell RW. Oxidation of human haemoglobin by copper. Mechanism and suggested role of the thiol group of residue beta-93. Biochem J. 1977;165:141–148. doi: 10.1042/bj1650141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattacharjee S, Deterding LJ, Jiang J, Bonini MG, Tomer KB, Ramirez DC, Mason RP. Electron transfer between a tyrosyl radical and a cysteine residue in hemoproteins: spin trapping analysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13493–13501. doi: 10.1021/ja073349w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia Y, Buehler PW, Boykins RA, Venable RM, Alayash AI. Structural basis of peroxide-mediated changes in human hemoglobin: a novel oxidative pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4894–4907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Augusto O, Lopes de Menezes S, Linares E, Romero N, Radi R, Denicola A. EPR detection of glutathiyl and hemoglobin-cysteinyl radicals during the interaction of peroxynitrite with human erythrocytes. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14323–14328. doi: 10.1021/bi0262202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isbell TS, Sun CW, Wu LC, Teng X, Vitturi DA, Branch BG, Kevil CG, Peng N, Wyss JM, Ambalavanan N, Schwiebert L, Ren J, Pawlik KM, Renfrow MB, Patel RP, Townes TM. SNO-hemoglobin is not essential for red blood cell-dependent hypoxic vasodilation. Nat Med. 2008;14:773–777. doi: 10.1038/nm1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson KM, Beckman JS. Synthesis of peroxynitrite from nitrite and hydrogen peroxide. Methods Enzymol. 2005;396:207–214. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)96019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas EL, Grisham MB, Jefferson MM. Preparation and characterization of chloramines. Methods Enzymol. 1986;132:569–585. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(86)32042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crawford JH, White CR, Patel RP. Vasoactivity of S-nitrosohemoglobin: role of oxygen, heme, and NO oxidation states. Blood. 2003;101:4408–4415. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cantu-Medellin N, Vitturi DA, Rodriguez C, Murphy S, Dorman S, Shiva S, Zhou Y, Jia Y, Palmer AF, Patel RP. Effects of T - and R-state stabilization on deoxyhemoglobin-nitrite reactions and stimulation of nitric oxide signaling. Nitric oxide : biology and chemistry / official journal of the Nitric Oxide Society. 2011;25:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dypbukt JM, Bishop C, Brooks WM, Thong B, Eriksson H, Kettle AJ. A sensitive and selective assay for chloramine production by myeloperoxidase. Free radical biology & medicine. 2005;39:1468–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stacey MM, Peskin AV, Vissers MC, Winterbourn CC. Chloramines and hypochlorous acid oxidize erythrocyte peroxiredoxin 2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1468–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Low FM, Hampton MB, Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. Peroxiredoxin 2 functions as a noncatalytic scavenger of low-level hydrogen peroxide in the erythrocyte. Blood. 2007;109:2611–2617. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-048728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landar A, Oh JY, Giles NM, Isom A, Kirk M, Barnes S, Darley-Usmar VM. A sensitive method for the quantitative measurement of protein thiol modification in response to oxidative stress. Free radical biology & medicine. 2006;40:459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heximer SP, Knutsen RH, Sun X, Kaltenbronn KM, Rhee MH, Peng N, Oliveira-dos-Santos A, Penninger JM, Muslin AJ, Steinberg TH, Wyss JM, Mecham RP, Blumer KJ. Hypertension and prolonged vasoconstrictor signaling in RGS2-deficient mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;111:445–452. doi: 10.1172/JCI15598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manta B, Hugo M, Ortiz C, Ferrer-Sueta G, Trujillo M, Denicola A. The peroxidase and peroxynitrite reductase activity of human erythrocyte peroxiredoxin 2. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;484:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tampo Y, Kotamraju S, Chitambar CR, Kalivendi SV, Keszler A, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. Oxidative stress-induced iron signaling is responsible for peroxide-dependent oxidation of dichlorodihydrofluorescein in endothelial cells: role of transferrin receptor-dependent iron uptake in apoptosis. Circ Res. 2003;92:56–63. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000048195.15637.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wardman P. Fluorescent and luminescent probes for measurement of oxidative and nitrosative species in cells and tissues: progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:995–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacMicking JD, Nathan C, Hom G, Chartrain N, Fletcher DS, Trumbauer M, Stevens K, Xie Q-w, Sokol K, Hutchinson N, Chen H, Mudget JS. Altered responses to bacterial infection and endotoxic shock in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Cell. 1995;81:641–650. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen FB. The dual roles of red blood cells in tissue oxygen delivery: oxygen carriers and regulators of local blood flow. J Exp Biol. 2009;212:3387–3393. doi: 10.1242/jeb.023697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niwa T, Naito C, Mawjood AH, Imai K. Increased glutathionyl hemoglobin in diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia demonstrated by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2000;46:82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takayama F, Tsutsui S, Horie M, Shimokata K, Niwa T. Glutathionyl hemoglobin in uremic patients undergoing hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Kidney International. Supplement. 2001;78:S155–S158. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.59780155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giustarini D, Dalle-Donne I, Colombo R, Petralia S, Giampaoletti S, Milzani A, Rossi R. Protein Glutathionylation in Erythrocytes. Clin Chem. 2003;49:327–330. doi: 10.1373/49.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iuchi Y, Okada F, Onuma K, Onoda T, Asao H, Kobayashi M, Fujii J. Elevated oxidative stress in erythrocytes due to a SOD1 deficiency causes anaemia and triggers autoantibody production. The Biochemical journal. 2007;402:219–227. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee TH, Kim SU, Yu SL, Kim SH, Park DS, Moon HB, Dho SH, Kwon KS, Kwon HJ, Han YH, Jeong S, Kang SW, Shin HS, Lee KK, Rhee SG, Yu DY. Peroxiredoxin II is essential for sustaining life span of erythrocytes in mice. Blood. 2003;101:5033–5038. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrer-Sueta G, Radi R. Chemical biology of peroxynitrite: kinetics, diffusion, and radicals. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:161–177. doi: 10.1021/cb800279q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pattison DI, Davies MJ. Reactions of myeloperoxidase-derived oxidants with biological substrates: gaining chemical insight into human inflammatory diseases. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;13:3271–3290. doi: 10.2174/092986706778773095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pimenova T, Pereira CP, Gehrig P, Buehler PW, Schaer DJ, Zenobi R. Quantitative Mass Spectrometry Defines an Oxidative Hotspot in Hemoglobin that is Specifically Protected by Haptoglobin. Journal of Proteome Research. 2010;9:4061–4070. doi: 10.1021/pr100252e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deterding LJ, Ramirez DC, Dubin JR, Mason RP, Tomer KB. Identification of free radicals on hemoglobin from its self-peroxidation using mass spectrometry and immuno-spin trapping: observation of a histidinyl radical. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11600–11607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramirez DC, Chen YR, Mason RP. Immunochemical detection of hemoglobin-derived radicals formed by reaction with hydrogen peroxide: involvement of a protein-tyrosyl radical. Free radical biology & medicine. 2003;34:830–839. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01437-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper CE, Schaer DJ, Buehler PW, Wilson MT, Reeder BJ, Silkstone G, Svistunenko DA, Bulow L, Alayash AI. Haptoglobin Binding Stabilizes Hemoglobin Ferryl Iron and the Globin Radical on Tyrosine beta145. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012 doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reeder BJ, Grey M, Silaghi-Dumitrescu RL, Svistunenko DA, Bulow L, Cooper CE, Wilson MT. Tyrosine residues as redox cofactors in human hemoglobin: implications for engineering nontoxic blood substitutes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:30780–30787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804709200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang H, Xu Y, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. Intramolecular electron transfer between tyrosyl radical and cysteine residue inhibits tyrosine nitration and induces thiyl radical formation in model peptides treated with myeloperoxidase, H2O2, and NO2-: EPR SPIN trapping studies. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:40684–40698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504503200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. Kinetics of the reactions of hypochlorous acid and amino acid chloramines with thiols, methionine, and ascorbate. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:572–579. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bateman RM, Jagger JE, Sharpe MD, Ellsworth ML, Mehta S, Ellis CG. Erythrocyte deformability is a nitric oxide-mediated factor in decreased capillary density during sepsis. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2001;280:H2848–H2856. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chatterjee A, Dimitropoulou C, Drakopanayiotakis F, Antonova G, Snead C, Cannon J, Venema RC, Catravas JD. Heat shock protein 90 inhibitors prolong survival, attenuate inflammation, and reduce lung injury in murine sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:667–675. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-291OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crawford JH, Chacko BK, Pruitt HM, Piknova B, Hogg N, Patel RP. Transduction of NO-bioactivity by the red blood cell in sepsis: novel mechanisms of vasodilation during acute inflammatory disease. Blood. 2004;104:1375–1382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagababu E, Rifkind JM. Reaction of hydrogen peroxide with ferrylhemoglobin: superoxide production and heme degradation. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12503–12511. doi: 10.1021/bi992170y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu L, Yan Y, Zeng M, Zhang J, Hanes MA, Ahearn G, McMahon TJ, Dickfeld T, Marshall HE, Que LG, Stamler JS. Essential roles of S-nitrosothiols in vascular homeostasis and endotoxic shock. Cell. 2004;116:617–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Asbeck BS, Hoidal J, Vercellotti GM, Schwartz BA, Moldow CF, Jacob HS. Protection against lethal hyperoxia by tracheal insufflation of erythrocytes: role of red cell glutathione. Science. 1985;227:756–759. doi: 10.1126/science.2982213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weiss SJ. Neutrophil-mediated methemoglobin formation in the erythrocyte. The role of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1982;257:2947–2953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grisham MB, Jefferson MM, Thomas EL. Role of monochloramine in the oxidation of erythrocyte hemoglobin by stimulated neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:6757–6765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Toth KM, Clifford DP, Berger EM, White CW, Repine JE. Intact human erythrocytes prevent hydrogen peroxide-mediated damage to isolated perfused rat lungs and cultured bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:292–295. doi: 10.1172/JCI111414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vissers MC, Winterbourn CC. Oxidation of intracellular glutathione after exposure of human red blood cells to hypochlorous acid. Biochem J. 1995;307(Pt 1):57–62. doi: 10.1042/bj3070057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]