Abstract

Objective:

Two measures of the response rate and the optimal treatment response for adult ADHD were evaluated using methylphenidate. The hypotheses were that Prediction of ADHD (PADHD) defines remission, the Weighed Core Symptom (WCS) scale registers direct effects of medication and that WCS may indicate the optimal dose level during titration.

Design:

PADHD and WCS were analyzed at baseline and after intake of low doses of either short-acting or modified-release formulations of methylphenidate, MPH (Study I), during titration with modified-release formulations of MPH (18/27, 36, 54, 72 mg) and at three months follow-up (Study II).

Patients:

Study I consisted of 63 participants (32 females) and Study II consisted of 10 participants (6 females) diagnosed with ADHD and who was to start with treatment.

Outcome measures:

Prediction of ADHD (PADHD) indicates the occurrence of ADHD (No, Yes) and the Weighed Core Symptom scale (WCS) quantifies ADHD from 0 to 100 (max-min).

Results:

The number of clinical cases of ADHD decreased after methylphenidate treatment according to PADHD. WCS increased (p < 0.001) from 9.75 (SD = 12.27) to 47.50 (SD = 29.75) with about 10 mg of methylphenidate (N = 63). During titration, symptoms improved after 18/27 mg and 36 mg of methylphenidate and baseline-follow up comparisons showed WCS increments (p = 0.005) from 31.00 (N = 10, SD = 26.85) to 69.00 (N = 10, SD = 22.34).

Conclusions:

PADHD defined remission and WCS measured therapeutic effects of methylphenidate in adult ADHD.

Keywords: Objective measures, Weighed Core Symptom scale, Prediction of ADHD, remission, ADHD.

BACKGROUND

Better long-term follow-up of treatment effectiveness with regard to predefined goals for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) among adults is warranted. Remission [1] is a criterion for treatment effectiveness and has been applied onto a number of psychiatric disorders in order to provide a rationale for the study and application of objective, measurable and clinically interpretable therapeutic end-points. The goal for treatment of ADHD in adults ought to be full remission but the exact definition and measurement of such improvements has just recently begun to evolve.

ADHD affects around 5 % of the adult population [2], including core symptoms of hyperactivity, inattention and impulsivity that constitute one out of three possible diagnostic subtypes [3]. Enormous societal costs, individual suffering and risks are associated with the disorder [4]. ADHD is also associated with severe under-treatment despite a massive body of cumulated research validating evidence-based treatments [5]. In order to gain as good a picture of ADHD symptom improvement during treatment as possible, one may employ both behavior ratings like the DSM-IV criteria [3] and more objective laboratory testing. One problem with rating scales is that they are built upon subjective observation and therefore likely to include biases but they are minimized when including also objective evaluation.

Monitoring treatment-efficacy involves evaluating the response to treatment defined as improvements in symptoms as a result of treatment [1]. The clinical trial response for ADHD has usually been set at 15-30 % improvement in symptom scores [6, 7]. In many cases, a patient who responds to this extent no longer meets the diagnostic criteria but since the initial level of symptoms is not accounted for there will also be responders who still have significant amounts of symptom and illness. In this regard, remission means “sufficient improvement” and has recently been introduced for ADHD [8] even though there is yet no universal agreement upon the criteria for remission in ADHD. In addition, females seek treatment to a higher extent than males, which suggests that there may be sex differences in the severity and course of the disorder. Recent meta-analytic work of laboratory measures in children with ADHD reported gender differences [9] and the response rate and optimal treatment response may be affected by gender differences as well.

Studies of goal-directed management with first-line treatment for ADHD demonstrate satisfactory results and patients may respond to the point that they become essentially asymptomatic and clinical criteria are no longer fulfilled [10-12]. Steele and colleagues [13] suggest that remission in ADHD be defined as “a loss of diagnostic status, minimal or no symptoms, and optimal functioning when individuals are being treated with or without medication” and further that “symptomatic remission can be operationalized as a mean total score of ≤1 on most standardized questionnaires”. There have been similar proposals of working definitions for remission in especially childhood ADHD based on cut-offs from behavior ratings like the Swanson Nolan And Pelham- version IV [14], the ADHD rating scale- version IV [15] and the Clinical Global Impression scale [16]. However, the use of quantifiable metrics with objective outcomes and standardized interpretation permit reliable estimation of treatment effectiveness and comparisons that may be of great value for the goal of remission.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate two prospective and objective measures of response and remission in adult ADHD using first-line treatment agencies for the disorder, i.e., methylphenidate. The instruments have been evaluated in terms of predictive power and the ability to quantify total amount of ADHD core symptoms in adults [17, 18]. The negative predictive value range was 95-96 %, the positive predictive value range was 57-63 %, sensitivity 86-87 % and specificity 83- 85 % [17, 18].

Measures are derived from the Quantified Behavior Test Plus, Qb-Test-Plus, a laboratory test specialized into the measurement of ADHD core symptoms in adulthood [19-21]. Previous studies suggest that the most reliable measure are attained from combining core symptom measures of hyperactivity, inattention and impulsivity into the composite Weighed Core Symptoms scale, WCS. The scale has been standardized with regard to adults with well-defined ADHD, non-ADHD normative participants, ADHD normative participants [17] and with regard to other psychiatric disorders presenting core symptoms of ADHD, e.g., bipolar II disorder, borderline personality disorder and participants with a disconfirmed ADHD-diagnosis [18]. The other instrument of interest for the present study is also derived from the Qb-Test-Plus and generates a categorical variable “Prediction of ADHD” (PADHD) that identifies clinical ADHD with good predictive power in a majority of cases [17, 18].

The aim was to evaluate WCS and PADHD in terms of response to treatment and remission during treatment with methylphenidate (MPH). We hypothesize that PADHD will indicate remission and that WCS will be sensitive to dose level changes, i.e., response, as well as to the clinically defined optimal dose level, i.e., remission.

In study I we evaluate the ability of WCS and PADHD to indicate response to treatment with short-acting MPH treatment. In study II we evaluate the ability of WCS to indicate dose responses and both instruments ability to indicate symptomatic remission during titration with modified-release MPH and at three months follow-up.

The hypotheses are that (a) PADHD may be used to define remission in adult ADHD, (b) WCS may register direct effects of medication with MPH in adults with ADHD, and (c) WCS may indicate optimal dose levels during titration with modified-release MPH.

STUDY I: METHODS

Participants

Study I consisted of 63 participants, 31 men and 32 women, with a mean age of 35.16 years (SD = 11.90). Participants had a diagnosis of ADHD at mean age 34.31 (SD = 11.58) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV [3]. Behavior ratings of Study I are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences (ps < 0.05) between men and women with regard to age or any of the behavior rating scales for ADHD.

Table 1.

Behavior Ratings.

Means (M) and Standard Deviations (SD) for Behavior Ratings Performed by Male and Female Participants with ADHD in Study I

| Males (n = 31) | Females (n = 32) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Behavior ratings | |||||

| WURS 25 | 100 | 50.29 | 20.43 | 51.66 | 16.14 |

| WRASS | 140 | 77.52 | 28.11 | 78.53 | 38.87 |

| ASRS-Total score | 72 | 40.00 | 17.04 | 46.34 | 11.12 |

| ASRS-Screener | 24 | 14.00 | 6.39 | 16.66 | 4.40 |

| CAARSS | 78 | 30.06 | 24.50 | 38.59 | 26.10 |

Design

Laboratory assessments of ADHD symptoms before and after clinical treatment with single doses of either short-acting or modified-release formulations of MPH was conducted. Levels of sensitivity and specificity for Prediction of ADHD (PADHD) were investigated using frequency distributions before (no, yes) and after (no, yes) treatment. Fisher´s exact test was employed to analyze treatment (baseline, follow-up) and PADHD (no, yes). A mixed design with analyses of variances was used with dependent variables of Hyperactivity, Inattention, Impulsivity and the Weighed Core Symptom scale (WCS). The independent variables were Treatment (before, after) and Gender (men, women).

Instruments

Qb-Test-Plus. This instrument [19-21] combines an XX-type Continuous Performance Test (CPT) installed as a software program on a PC and an activity test during 20 minutes. While performing the CPT on the computer, movements of the participants are recorded using an infrared Motion Tracking System (MTS) following a reflective marker attached to a head-band. The CPT involves rapid presentation of stimuli involving color (blue, red) and shape (circle, square) on the screen and participants are instructed to press a hand-held button when stimuli repeats itself (a target) and not to press the button when stimuli varies relative to the previous one (a non-target). The stimuli are presented at a pace of one per two seconds, each one visible for 200 milliseconds, and the total number of stimuli is 600, presented with a 25 % target probability. The purpose of Qb-Test-Plus is to provide objective information regarding cardinal symptoms of ADHD; hyperactivity on basis of motor-activity measured with the camera, and inattention and impulsivity on basis of the CPT-test [19]. Operationalization of variables was done according to a previous study [17]. Hyperactivity was operationalized with the parameter called "distance", i.e., the length (meter) of the path travelled by the headband reflector during the test. Inattention was operationalized as omission errors and impulsivity was operationalized as commission errors.

Weighed Core Symptoms scale (WCS). This scale summarizes the total level of ADHD core symptoms in adults on a scale with ten cut-points ranging from 0 to 100 [17] where 0 indicate maximal amount of and 100 indicate complete absence of ADHD symptoms. The scale is based upon raw scores from the summed and operationalized measures from the Qb-Test-Plus in which the results of hyperactivity have been multiplied with three, inattention with two and impulsivity with one. The ten cut-points of WCS were developed through a procedure previously described [17]. In the present study, WCS correlated (Pearsons’ r) with baseline measures of hyperactivity (r = 0.80, p < 0.001), inattention (r = 0.62, p < 0.001), but not with impulsivity (p > 0.05).

Prediction of ADHD (PADHD). This categorical predictor variable [17] regarding ADHD (No/Yes) is based on ADHD behavioral measures from the Qb-Test-Plus (Q-scores), i.e., hyperactivity measured in distance, inattention measured with omission errors and impulsivity measured with commission errors. PADHD was developed using qualitative analyses and assessment trials in which the level of sensitivity and specificity was evaluated. The variable generates 86 % sensitivity and 83 % specificity when predicting ADHD versus normative participants from the adult general population, and the probability of PADHD making a correct classification regarding ADHD was 83 and 85 % respectively [17, 18].

The Adult Self Report Scale for Adult ADHD v1.1 (ASRS). This screening instrument [22] is derived from the criterions of ADHD in DSM-IV. Part A is the screener and includes the 6 most predictive items while part B holds an additional 12 items, all rated on a five-point scale. The maximum total score for the scale is 72 and 24 for the screener. A value of nine or more on the screener indicates ADHD with high probability [22].

Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS). This scale [23, 24] retrospectively measures the severance of ADHD symptoms in childhood on a 5 point scale (0= not at all/only a little, 1= to some extent, 2= a lot, 3= severely, 4= completely). Adult subjects rate 61 items related to relevant areas, and 25 of the questions are especially sensitive to ADHD [23]. A cut- off of 46 on the 25-item screener (maximum score of 100) is indicative of ADHD.

Wender Reimherr ADHD Symptoms Scale for Patients (WRASS 1). WRASS [23] estimates symptoms of ADHD from the adult patients point of view on a 5-point scale (0= not at all/only a little, 1= to some extent, 2= a lot, 3= severely, 4= completely). The scale covers areas of attention, hyperactivity, instability of mood, organizational difficulties, sensitivity to stress and impulsivity and is commonly used in Swedish psychiatry with a clinical cut-off of 69, maximum score is 140.

Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale- Short version (CAARSS). This official self-report short-version scale [25] measures 26 items related to four areas of adult ADHD: Inattention, Hyperactivity/restlessness, Impulsivity/emotional lability and problems with self-concept on a four-point scale (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = often, 3 = very often) and the maximum score is 78.

Procedure

The current study belongs to a series of investigations performed by the present authors and approved in 2008 by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (Dnr: 2008/110/2). ADHD-assessments had previously been carried out at the Clinic of neuropsychiatry and CBT, Cereb (n = 51), the psychiatric clinic of the County Council in Varmland (n = 11) or the NU-health-care psychiatric clinic, all Swedish (n = 1). Neuropsychiatric assessments were carried out with similar neuropsychological procedures and included for example retrospective and current medical anamnesis, first- and second part behavior ratings and structured interviews, and psychological tests of memory and attention. In most cases (n = 51), assessments included also the unstandardized report of Qb-Test-Plus. Inclusion criterions were 18 to 65 years of age, diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-IV [3], described chronic course of ADHD symptoms in childhood with some symptoms present before age seven and continue to meet DSM-IV criteria at the time of assessment.

Testing was standardized and performed individually. Participants became seated in front of the PC using a chair without armrests in order to ensure a non-reclining body-position. Instructions were given both verbally and with a standardized video [19]. Participants performed a one minutes pre-test to ensure the instructions had been understood correctly. Participants performed the Qb-Test-Plus for 20 minutes in a room with minimal sensory stimuli. Measures were performed at the same day at 103.16 minutes (SD = 55.36) from oral intake of MPH (n = 51), or some days (M = 13.75, SD = 21.55, range = 1 to 60 days) after baseline at 193.43 minutes (SD = 122.51) from oral intake of MPH (n = 12). Participants were ordinated a short-acting formulation of 10 mg (n = 35) or 20 mg (n = 18) of MPH, or a modified-release formulation of 18 mg of MPH (n = 9) from doctors. One participant was ordinated 54 mg of a modified-release formulation and hence the mean average dosage for the entire sample (N = 63) was 13.69 mg (SD = 6.97, range = 10 to 54). Subjects were informed that enrollment was voluntary and that dropping-out would not interfere with medical treatment or other health-care. The informed consent was signed before any study-related procedures. Participation was associated with travel reimbursement.

STUDY I: RESULTS

Prediction of ADHD

Sensitivity and specificity for Prediction of ADHD was investigated using frequency tables for baseline and treatment conditions. Results are presented in Table 2. Fisher´s Exact Test (5 % level) indicated most participants in the yes-ADHD condition before treatment and in the no-ADHD condition after treatment (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Effects of Prediction of ADHD.

Effects of Prediction of ADHD (No/Yes ADHD), PADHD, for the Baseline and the Treatment condition with a short-acting MPH formulation in a single-dose study including 63 adult participants with ADHD (32 females). The table shows the absolute and relative frequency for PADHD at baseline and during treatment

| Prediction of ADHD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| Condition | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent |

| Baseline | 8 | 12.7 | 55 | 87.3 |

| Treatment | 39 | 61.9 | 24 | 38.1 |

Treatment and Gender Differences with Regard to Dependent Variables

A mixed Pillai’s MANOVA (2 x 2 factorial design) was conducted with Treatment (before, after) and Gender (men, women) as independent variables, and Hyperactivity, Inattention and Impulsivity as dependent variables. The analysis revealed significant effects for Treatment (p < 0.001, Eta2 = 0.74, power > 0.99), and Gender (p = 0.038, Eta2 = 0.132, power = 0.68), but not for the interaction Group x Gender (p = 0.357, Eta2 = 0.053, power = 0.28).

Core Symptoms. Univariate F-tests revealed significant effects with regard to Treatment for Hyperactivity [F (1, 61) = 115.44, p < 0.001], Inattention [F (1, 61) = 97.19, p < 0.001], and Impulsivity [F (1, 61) = 25.82, p < 0.001] where the before treatment condition generated lower scores on all variables (indicating higher symptom levels) as compared to the after treatment condition. With regard to Gender, univariate F-tests revealed a significant effect only for Inattention, [F (1, 61) = 8.00, p = 0.006] but not for Hyperactivity or Impulsivity (ps > 0.05). Further analyses showed that women had lower scores on Inattention, indicating higher symptom levels, as compared to men. Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive Data for Dependent Variables.

Means (M) and Standard Deviations (SD) for Hyperactivity, Inattention, Impulsivity and Weighed Core Symptoms (WCS) Scale with Regard to Before and after Treatment with Short-Acting or Modified-Release Formulations of MPH with Regard to Men (n = 31), Women (n = 32) and the Total Group of Adult Participants with ADHD (N = 63)

| Before | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Total | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Hyperactivity | 27.83 | 23.54 | 24.30 | 20.90 | 26.04* | 22.11 |

| Inattention | 38.14 | 14.21 | 29.19 | 14.99 | 33.60* | 15.18 |

| Impulsivity | 61.20 | 28.55 | 56.92 | 30.87 | 59.02* | 29.59 |

| WCS | 13.23¤ | 16.61 | 6.25¤ | 7.93 | 9.68* | 13.32 |

| After | ||||||

| Men | Women | Total | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Hyperactivity | 65.14 | 17.98 | 50.98 | 22.37 | 59.95* | 21.39 |

| Inattention | 57.21¤ | 17.08 | 46.88¤ | 15.30 | 51.94* | 16.83 |

| Impulsivity | 77.51 | 23.04 | 70.22 | 23.17 | 73.81* | 23.21 |

| WCS | 60.00¤ | 29.44 | 35.00¤ | 30.05 | 47.30* | 32.09 |

Note. Higher values indicate lower levels of ADHD symptoms; The asterisk (*) indicates significant differences between baseline and follow-up; The square (¤) indicates significant interaction-effects for gender and condition.

WCS. Since the Weighed Core Symptom scale is a composite measure it was analyzed separately with a mixed ANOVA. The analyses showed significant effects for Treatment [F (1, 61) = 101.782, p < 0.001], Gender [F (1, 61) = 13.16, p < 0.001] and for the interaction Treatment x Gender [F (1, 61) = 5.80, p < 0.05]. Descriptive analyses showed that the baseline condition was associated with lower scores (indicating higher symptom levels) than the treatment condition, and that men in the treatment condition had higher scores (indicating lower symptom levels) than women in the treatment condition. Regarding the interaction effect, descriptive analyses showed that men gained more improvement from treatment than women. Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 3.

STUDY II: METHODS

Participants

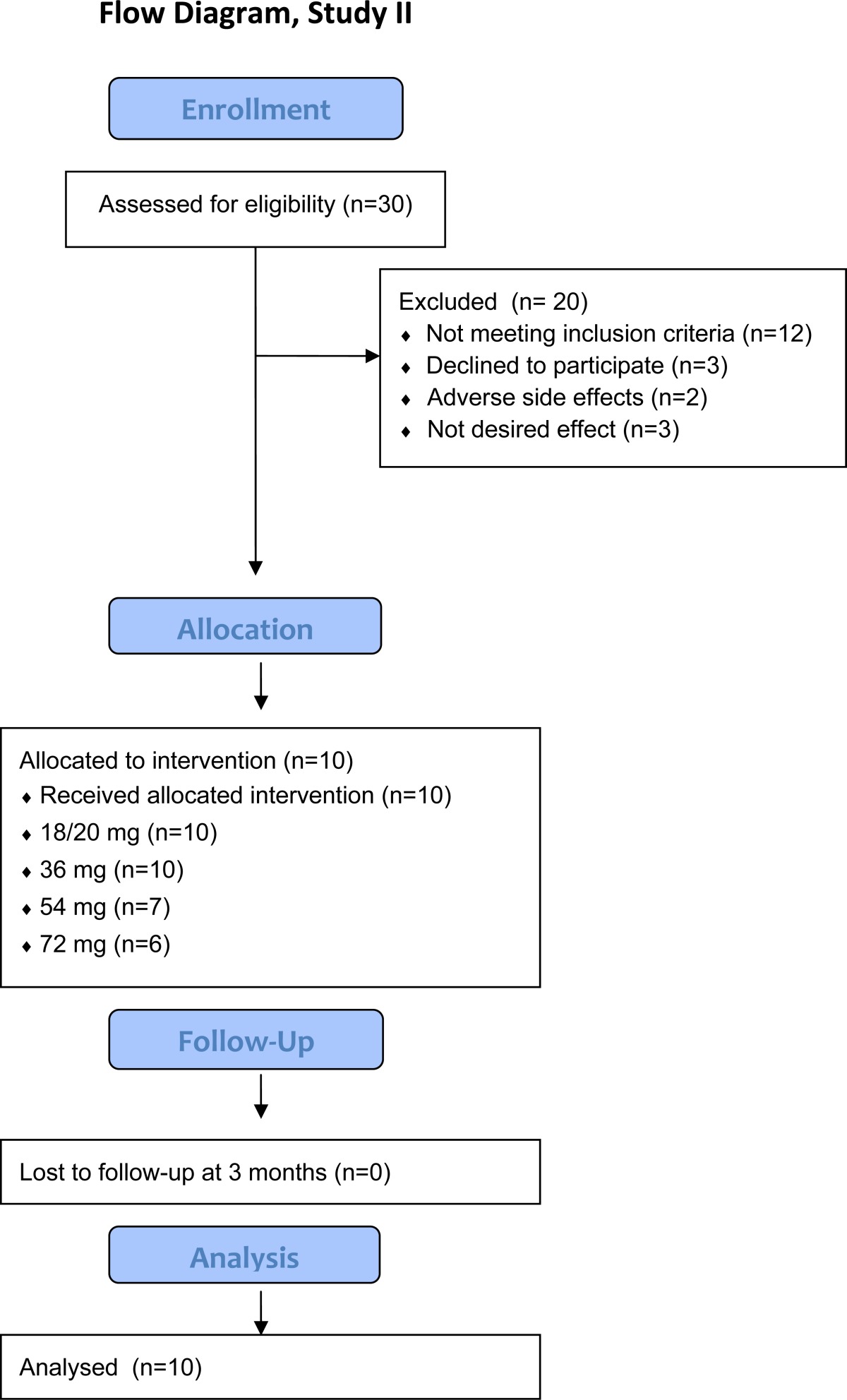

A total of 30 participants were assessed for eligibility but 20 of them dropped-out, see Table 7. Thus, Study II consisted of 10 participants, 4 men and 6 women, with an ADHD diagnosis according to DSM-IV [3] and whose first MPH- dose was to be initiated and titrated. Behavioral data are presented in Table 6. Participants were outpatients previously diagnosed with ADHD at the psychiatric clinic in the county council of Varmland (n = 8) or in the NU-health care psychiatric clinic (n = 2). Neuropsychiatric assessments included psychiatric and medical anamnesis, first- and second part behavior ratings and structured interviews, and psychological tests of memory and attention. In four cases, additional tests of cognitive functioning, intelligence, memory and attention were also included. Inclusion criterias were 18 to 65 years of age, diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-IV, described chronic course of ADHD symptoms in childhood with some symptoms present before age seven and continue to meet DSM-IV criteria at the time of assessment.

Table 7.

Flow Chart of Study II

|

Table 6.

Descriptive Data for Subjective Ratings.

Means (M) and Standard Deviations (SD) of the Behavior Rating Scales of the Present Study, Presented for the Baseline and follow-up Conditions. Treatment consisted of a Modified-Release Formulation of MPH in 10 adults (6 females) with ADHD

| Baseline Follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| ASRS-Total | 48.20 | 3.82 | 30.78* | 8.87 |

| WRASS CAARSS |

96.20 55.90 |

19.85 13.00 |

61.44* 36.33* |

19.18 11.74 |

Note. Higher values indicate higher levels of ADHD symptoms; All baseline and the follow-up differences were significant (*) ASRS-T; Adult ADHD Self Rating Scale Total score, WRASS; Wender Reimherr ADHD Symptom Scale, CAARSS; Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale- Short version.

Design

Pre- and post titration analyses with PADHD (no/yes ADHD) included levels of sensitivity and specificity. Dependent variables were objective measures of Hyperactivity, Inattention, Impulsivity and WCS. Measures were collected at baseline, for each dose level (18/27, 36, 54, 72) and for the optimal dose level follow-up at three months. Wilcoxon signed rank test (5 % level) was used to analyze titration effect upon dependent variables and behavior ratings.

Instruments

All instruments are presented in the instruments section of Study I.

Procedure

General study procedures are described in Paper I. Titration time total was individual with one to four weeks interval between each increment of the dose level. Modified-release MPH were ordinated starting at 18 and 27 mg respectively. Study measures were obtained at minimum one to maximum seven days from each increment of the dose level and the psychometric testing generally occurred at 103.16 minutes (SD = 55.36) from oral intake. The treatment follow-up was standardized to twelve weeks after the initiation of each patients optimal dose level. Titration was entirely governed by doctors and patients, both blinded from the study measures. Subjects were informed that enrollment was voluntary and that dropping out of the study would not interfere with medical treatment or other health-care. Drop-outs (N = 20) are not analyzed in this pilot study, see Table 7.

STUDY II: RESULTS

Prediction of ADHD

Sensitivity and specificity for ADHD at pre- and post titration are in Table 4.

Table 4.

Effects of Prediction of ADHD Pre- and Post- Treatment.

Effects of Prediction of ADHD before (No/Yes ADHD) and after (No/Yes ADHD) Treatment

| Prediction of ADHD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| Condition | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent |

| Baseline | 2 | 20 | 8 | 80 |

| Follow-up | 9 | 90 | 1 | 1 |

WCS and Core Symptom Measures at Pre- and Post Titration

The Wilcoxon signed rank test (5 % level) was employed to assess pre- and post titration conditions with regard to WCS and core symptom measures. WCS was significantly different between the two conditions (Z = 2.82, p = 0.005). Hyperactivity was not significantly different (p = 0.059). However the result could be regarded as a non-significant trend since a Paired-Samples t-test (5 % level) yielded a significant effect t (9) = -2.34, p = 0.044. Inattention was significantly different (Z = 2.70, p = 0.007) and finally, Impulsivity differed between the two conditions (Z = 2.20, p = 0.028). For means and standard deviations see Table 5.

Table 5.

Descriptive Data for Dependent Variables at Dose Levels.

Means (M) and Standard Deviations (SD) for Hyperactivity, Inattention, Impulsivity and Weighed Core Symptoms (WCS) Scale with Regard to Dose Levels. Treatment Consisted of a Modified-Release Formulation of MPH in 10 Adults (6 Females) with ADHD

| WCS | Hyperactivity | Inattention | Impulsivity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Baseline | 31.00* | 26.85 | 60.30* | 25.90 | 34.30* | 10.86 | 62.43* | 25.38 |

| 18/27 mg | 38.75¤ | 31.82 | 61.57 | 22.22 | 43.04 | 16.35 | 65.71 | 15.54 |

| 36 mg | 55.00¤ | 28.38 | 68.96 | 11.71 | 52.41 | 23.71 | 74.71 | 14.58 |

| 54/72 mg | 77.14 | 24.98 | 73.77 | 15.41 | 61.48 | 11.64 | 87.14 | 5.15 |

| Follow-up | 65.00 69.00* |

33.32 22.34 |

75.62 73.88* |

18.56 11.86 |

52.37 55.19* |

30.64 17.37 |

86.43 81.29* |

6.31 10.62 |

Note. Higher values indicate lower levels of ADHD symptoms; The asterisk (*) indicates significant differences between baseline and follow-up; The square (¤) indicates significant differences from the tabulated value above.

WCS and Core Symptom Measures During Titration

The Wilcoxon signed rank test (5 % level) was employed to assess WCS and core symptom measures during titration. Baseline versus the 18/27 mg condition yielded significant differences for WCS (Z = 2.25, p = 0.024) but not for Hyperactivity, Inattention or Impulsivity (ps > 0.05). The 18/27 versus 36 mg comparison yielded significant differences for WCS (Z = 2.06, p = 0.039) but not for Hyperactivity, Inattention or Impulsivity (ps > 0.05). Comparing the 36 vs. 54 mg and the 54 vs. 72 mg yielded no significant differences for any of the measures (ps > 0.05). For means and standard deviations see Table 5.

Subjective Measures of Treatment Response

A Wilcoxon signed rank test (5 % level) was employed to assess baseline and follow-up conditions with regard to Wender Adult ADHD Rating Scale (WRASS), the ASRS self-rating scale (ASRSS) and the Conner’s Adult ADHD Self Rating Scale Short Version (CARSS). Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 6. WRASS was significantly different between the two conditions (Z = -2.31, p = 0.021) and descriptive statistics showed that the baseline condition had a significantly higher mean score than the follow-up condition. The ASRS self-ratings were significantly different (Z = -2.67, p = 0.008) and higher at baseline than during follow-up. CAARSS also differed between the two conditions (Z = -2.67, p = 0.008) and were higher during baseline than follow-up. It should be noted that higher scores indicates higher levels of ADHD symptoms for all measures whereas higher values of WCS indicates lower levels of ADHD symptoms.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present investigation was to evaluate two measures of pharmacotherapy in adult ADHD using short-acting and modified-release formulations of methylphenidate. We hypothesized that (a) PADHD may be used to define remission, (b) WCS may register direct effects of medication with methylphenidate and (c) WCS may indicate optimal dose levels during titration.

The first hypothesis was accepted since in Study I, PADHD correctly classified 87 % of the sample as having ADHD and 62 % of the sample achieved remission. In Study II, 80 % of the sample was correctly classified as having ADHD and 90 % achieved remission. The results of PADHD were validated by the blinding of doctors and patients and were also confirmed by the significant improvements and correlations with behavior ratings, i.e., ASRS, CAARSS and WRASS. It was encouraging that PADHD validated the subjective ratings even though these failed to differentiate dose level improvements.

The second hypothesis was accepted since in Study I, decreased levels of symptoms were registered after low doses of short-acting or modified-release formulations of MPH-treatment. Here, descriptive analyses reported increments of WCS from 9.75 (SD = 12.27) to 47.50 (SD = 29.75). The results of WCS were lower (indicating higher levels of symptoms) than the results of non-ADHD normative participants in previous studies [17, 18], i.e., WCS of 63.83 (SD = 25.72) and 67.47 (SD = 24.07), respectively. This indicates that at least some of the participants had not yet gained full effect from their treatment, i.e., being responders rather than remitters, and that their dose level needed adjustment. In Study II, it was evident that the MPH-treatment decreased symptoms (p = 0.005) from 31.00 (SD = 26.85) at baseline to 69.00 (SD = 22.34) at follow-up and results are consistent with previous findings of PADHD and WCS [17, 18].

The third hypothesis was accepted since in Study II, symptoms improved from WCS 31.00 (SD = 26.85) to WCS 38.75 (SD = 31.82) at 18/27 mg of MPH (p < 0.001). Moreover, WCS reported lower symptoms (M = 55.00, SD = 28.38, p < .001) when increasing the dose level to 36 mg of MPH. However, WCS did not indicate lower symptoms when increasing the dosage from 36 to 54 mg (p >.05) or from 54 to 72 mg of MPH (p >.05). WCS was investigated here in terms of discerning changes in dose levels rather than a dose level response per see. It may be interesting to know that WCS yielded symptom level decrement between baseline and all of the investigated dose levels. But none of the core symptom measures or rating scales was sensitive enough to detect responses to changes in dose level. There were no overall significant differences for gender. Most participants had combined type ADHD with minimal psychiatric comorbidity which may have facilitated the measurement of response and remission as well as contributed to the intervention outcome. The study have several additional limitations, e. g., the low number of participants and especially in Study II, the high level of drop-outs in Study II, the lack of standardized administration of the MPH, the use of both short-release and modified-release formulations of MPH in Study I, the decreased number of participants at the higher dose levels and the use of non-parametric statistics in Study II and the lack of measures for functional improvements, e.g., global assessment of functioning, for comparison with WCS and PADHD are some of the examples of the many limitations of the present study.

CONCLUSIONS

The present investigation proposed definition and measurement of response and remission using two new instruments for adult ADHD. PADHD and WCS were effective measures of response and remission during pharmacotherapy with short-acting and modified-release formulations of methylphenidate and their ability to calibrate treatment for adults with ADHD was supported. Outcome from prolonged duration of remission and its consequences for the functional ability needs to be given in future studies and the intervention ought to be monitored in terms of global effects on health and psychiatric status. The instruments are proposed as objective tools that may complement behavior ratings and other clinical information in order to monitor therapeutic efficacy in clinical trials and to evaluate intervention studies. WCS and PADHD may also have potential practical implications since it is important for clinicians and patients to have robust and well-defined outcome-criteria in order to evaluate and improve treatment for adult ADHD. Further studies are encouraged in well-being and functional improvements.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all participants. The study was supported by unrestricted grants from the County Council of Värmland, Sweden (98 % of total cost), and Janssen-Cilag AB, Sollentuna, Sweden (2 % of total cost). Authors acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Britt-Marie Hansson, Carolyn Isaksson, Kerstin Ling, Fredrik Ulberstad, Hans Boström, and Petter Knagenhjelm.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

HE collected and analyzed the material, drafted the manuscript and approved the finalized version. LH designed the study, analyzed the material and approved the finalized version. TN conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed the material, drafted the manuscript and approved the finalized version.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, et al. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder.Remision.recovery., relapse and recurrence. . Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999; 48:851–5. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810330075011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United Sates: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry . 2006.;163:716–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th ed Washington DC. American Psychiatric Association. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matza LS, Paramore C, Prasad M. A review of the economic burden of ADHD. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2005;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kooij SJ, Bejerot S, Blackwell A, et al. European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The Eu-ropean Network Adult ADHD. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelsey DK, Summer CR, Casat CD, et al. Once-daily atomoxetine treatment for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. including assessment of evening and morning behavior: a double-bind.placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, et al. Efficacy of a mixed amphetamine salts compound in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:775–82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramos-Quiroga A, Casas M. Achieving remission as a routine goal of pharmacotherapy in attention-deficit hy-peractivity disorder. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:17–36. doi: 10.2165/11538450-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasson R, Goldenring Fine J. Gender differences among children with ADHD on continuous performance tests: a meta-analytic review. J Atten Disord. 2012;16:190–8. doi: 10.1177/1087054711427398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Retz W, Rösler M, Ose C, et al. Multiscale assessment of treatment efficacy in adults with ADHD: a randomized pla-cebo-controlled multi-centre study with extended-release methylphenidate. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13:48–59. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2010.540257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rösler M, Fischer R, Ammer R, Ose C, Retz W. A randomized placebo-controlled 24-week. study of low-dose extended-release methylphenidate in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur Arch Psychol Clin Neurosci. 2009;259:120–9. doi: 10.1007/s00406-008-0845-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, et al. A large double-blind randomized clinical trial of methylphenidate in the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:456–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steele M, Jensen PS, Quinn DMP. Remission versus response as the goal of therapy in ADHD: a new standard for the field?. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1892–908. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swanson J. SNAP-IV scale Irvine California University of California Irvine Child. Development Center. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 15.DuPaul G, Reid R, Power T, Anastopoulos A. ADHD Rating Scale-IV: checklists. norms and clinical inter-pretations. New ork. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guy W. ECDEU: Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology Revised Rockville MD. US Department of Health Education and Welfare. 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edebol H, Helldin L, Norlander T. Measuring adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder with the Quantified Behavior Test Plus. Psychol J. 2013;2(1):48–6. doi: 10.1002/pchj.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edebol H, Helldin L, Norlander T. Measuring adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with the quantified behaviour test plus. Psychol J. 2013;2(1):48–62. doi: 10.1002/pchj.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.QbTech AB. QbTest Plus Clinical Manual. Gothenburg Sweden. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 20.QbTech AB. QbTest Plus Technical Manual. Gothenburg Sweden. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 21.QbTech AB. QbTest Plus Operational Manual. Gothenburg Sweden. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler CR, Adler L, Ames M, et al. The world health organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35:245–56. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah rating scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:885–90. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wender PH. Wender AQCC (Adult-Childhood Characteristics) scale. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21:927–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conners CK, Erhardt D, Sparrow E. Adult ADHD rating scales: Technical manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems. 1999 [Google Scholar]