Abstract

Tissue injury, such as burns or inflammation, can lead to the generation of oxidized lipids capable of regulating hemodynamic, pulmonary, immune and neuronal responses. However, it is not known whether traumatic injury leads to a selective up-regulation of transcripts encoding oxidative enzymes capable of generating these mediators. Here, we analyzed microarrays taken from circulating leukocytes of 187 trauma subjects compared to 97 control volunteers for changes in expression of 105 oxidative enzymes and related receptors. The results indicate that major blunt trauma triggers a selective change in gene expression with some transcripts undergoing highly significant up-regulation (e.g., CYP2C19), while others displaying significantly reduced expression (e.g., CYP2U1). This pattern in gene expression was maintained for up to 28 days after injury. In addition, the level of expression of CYP2A7, CYP2B7P1, CYP2C19, CYP2E1, CYP4A11, CYP4F3, CYP8B1, CYP19A1, CYP20A1, CYP51A1, HMOX2, NCF1, NCF2, NOX1, and the receptors PTGER2 and ESR2 were correlated with clinical trauma indices such as APACHE II, Max Denver Scale and the Injury Severity Score. Demonstration of a selective alteration in expression of transcripts encoding oxidative enzymes reveals a complex molecular response to major blunt trauma in circulating leukocytes. Further, the association between changes in gene expression and clinical trauma scores suggests an important role in integrating pathophysiologic responses to blunt force trauma.

Keywords: Trauma, Cytochrome P450, Lipoxygenase, Oxidized Linoleic Acid Metabolites, Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid, Gene Expression

INTRODUCTION

Enzymatic-mediated release of oxidized lipids is known to occur in severe types of injury. For example, severe burns trigger the release of leukotoxin, an oxidized linoleic acid metabolite produced by leukocytes that is associated with circulatory shock, acute respiratory distress, and multi-organ failure (1–4). Moreover, circulating levels of certain oxidized linoleic acid metabolites are positively correlated with burn severity (1). In addition, oxidized metabolites of arachidonic acid are released in conditions such as UV damage to skin (5, 6) or minor surgery (7). Thus, the formation of biologically active oxidized lipids likely contributes to the pathophysiologic responses of severe tissue injury.

The mechanisms by which polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) can be oxidized to form active metabolites include enzymatic reactions (i.e., cytochrome p450 enzymes (CYP), lipoxygenases (LOX) or cyclooxygenases (COX)) as well as non-enzymatic oxidation (8–10). In particular, recent studies implicate a key role of the CYP, LOX and COX enzymes in contributing to formation of oxidized linoleic and arachidonic acid metabolites after inflammatory tissue injury (9, 10). While PUFAs are known to be synthesized under a range of inflammatory conditions (11–14), it is not known whether trauma leads to an increase in the enzymatic machinery capable of releasing these biologically active lipids.

Based upon these findings, we hypothesized that traumatic injury would lead to a selective up-regulation of transcripts encoding oxidative enzymes capable of generating oxidized PUFAs. Accordingly, we analyzed a large database of microarrays collected from circulating leukocytes of major trauma subjects compared to control volunteers. This database was analyzed for changes in expression pattern of candidate enzymes and receptors to determine the pattern of gene response and its maintenance during blunt traumatic injury.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Glue Grant Database

The Glue Grant Trauma-Related Database (TRDB) was used to identify gene-expression patterns in circulating peripheral leukocytes using microarray methodologies. The TRDB was developed in 2001 as part of the Inflammation and Host Response to Injury large scale collaborative program that was federally funded by the NIGMS. The consortium included six trauma centers (15). The purpose of this multicenter cohort study was to develop a large, relational database containing clinical findings, baseline patient characteristics, and gene expression in circulating peripheral leukocytes to determine the relationships among genes and their expression patterns over time after injury (16). Accessing and analyzing this de-identified database was approved by the University of Texas Health Sciences Center San Antonio Institutional Review Board and the Inflammation and Host Response to Injury Consortium.

Sample Collection, Processing and Microarray Analysis

Blood samples were processed immediately at the clinical site and frozen for later analysis. The buffy coat, consisting of circulating leukocytes, was isolated using previously validated methods and total RNA was extracted and processed for hybridization to the Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus 2 human gene chip at a central core lab (17). Detailed descriptions for all protocols and specific laboratory methodologies have been published previously (17, 18). The normalization of gene chip expression signal was performed with the DNA Chip Analyzer, dChip version 1.3 (17).

Subjects

A complete list of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for subject enrollment is provided in Table 1. There were 187 trauma patients that had samples taken at various times points up to 28 days from injury that correspond to 785 microarrays. The blunt trauma injury group was compared to a control group. There were 97 subjects enrolled in the control group that supplied peripheral circulating leukocytes (Table 1). The clinical and demographic data were collected using standardized case forms.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the Trauma Subjects

| Inclusion Criteria |

| Blunt trauma without isolated head injury |

| Absence of TBI (AIS head < 4 OR GCS motor > 3 within 24 hours of injury |

| Emergency department arrival ≤ 6 hours from time of injury |

| Blood transfusion within 12 hours of injury |

| Base deficit ≥ 6 OR systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg within 60 minutes of emergency department arrival |

| Fully or partially intact cervical spinal cord |

| Exclusion Criteria |

| Age < 16 |

| Anticipated survival of < 24 hours from injury |

| Anticipated survival < 28 days due to pre-existing medical condition |

| Inability to obtain first blood draw within first 12 hours after injury |

| Traumatic brain injury (GCS ≤ 8 after ICU admission AND brain CT scan abnormality within first 12 hours after injury |

| Inability to obtain informed consent |

| Pre-existing, ongoing immunosuppression (transplant recipient, chronic high dose steroids > 20mg/prednisone-equivalent per day), oncolytic drug therapy within the past 14 days, HIV positive AND CD4 count < 200 cells/mm3) |

| Possible requirement for early immunosuppression |

| Significant pre-existing organ dysfunction |

| -- Heart: congestive heart failure |

| -- Lung: currently receiving home oxygen therapy |

| -- Renal: chronic renal failure (creatinine > 2) |

| -- Liver: cirrhosis with portal hypertension or encephalopathy |

Statistical Analysis

We conducted a freeform search of the TRDB of the trauma injury group and collected information on all patients who had peripheral circulating leukocyte samples analyzed by the Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus 2 human genome chip. In this study, a total of 105 genes were selected for analysis, including 86 genes know to oxidize PUFAs, the general class of lipids that includes linoleic acid and arachidonic acid. A complete list of the analyzed genes is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of Genes selected for analysis

| Enzymes | |

| Cytochrome P450 | 59 |

| Lipoxygenase | 8 |

| Bradykinin | 2 |

| Calcitonin | 2 |

| Cyclooxygenase | 2 |

| Cytochrome b-245 | 2 |

| Epoxide Hydrolase | 4 |

| Heme Oxygenase | 2 |

| Neutrophil Cytosolic Factor | 2 |

| Nitric Oxide Synthase | 4 |

| NADPH Oxidase | 6 |

| Prolactin | 1 |

| Protachykinin | 1 |

| Receptors | |

| Estrogen Receptor | 2 |

| Opioid Receptors | 3 |

| Prolactin Receptor | 1 |

| Prostaglandin E Receptor | 2 |

| TRPV1 | 1 |

| TRPA1 | 1 |

| TRPV3 | 1 |

For our statistical analysis we first compared cases to controls. The longitudinal data was split into intervals based on time after trauma, and we averaged each gene’s log2 expression for each individual within each interval. The case averages within an interval were compared to the control averages using a t-test using Bonferroni corrections. Second, we examined the cases to identify associations of the clinical features and outcomes of the trauma patients with gene expression. For the continuous clinical features, we computed Pearson correlation coefficients with gene expression for each time interval, and we used the Cox proportional hazards model to estimate associations with gene expression values within an interval and survival time. All tests of association were two-sided, and all computations were performed with the statistical software R v2.15 (Vienna, Austria). The analysis of metabolic pathways associated with identified genes was conducted using GeneMania developed by Warde-Farley, et al (19).

RESULTS

Demographics

Demographic information for the trauma subjects and the controls is presented in Table 3. In general, the trauma group (n=187) and the control groups (n=97) were similar although control subjects tended to be younger in age.

Table 3.

Demographics

| Trauma Patients | |

| Patients, N | 187 |

| Age, mean (range), years | 34 (16 – 55) |

| Male, N (%) | 118 (63%) |

| Injury Severity Score, mean (range) | 31 (6 – 75) |

| APACHE II Score, mean (range) | 27 (10 – 42) |

| Marshall Score, mean (range) | 5.37 (0.42 – 16.39) |

| Denver Score, mean (range) | 2.15 (0 – 11) |

| Death, N (%) | 8 (4%) |

| CONTROL SUBJECTS | |

| Patients, N | 97 |

| Age, mean (range), years | 18 (7 – 63) |

| Male, N (%) | 53 (55%) |

| Previous burn injury, N (%) | 30 (31%) |

Changes in Gene Expression after Trauma

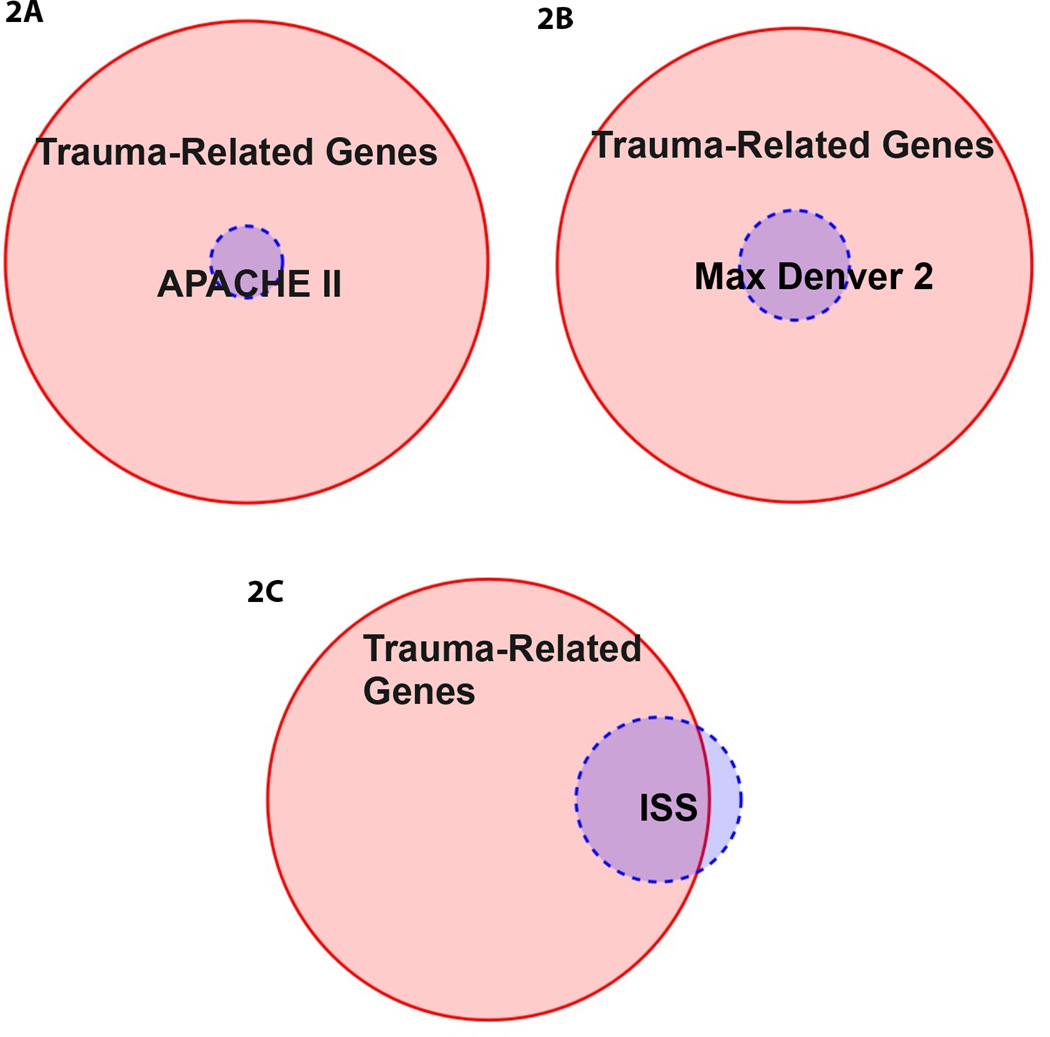

The initial analyses evaluated the difference in gene expression levels between the trauma subjects and the non-injured controls. Figure 1 is a heat map of the difference of gene expression using a log 2 scale (i.e., each unit increase indicates a doubling in expression). For this analysis the collected samples were separated by time periods to permit evaluation of temporal responses to injury (20–23). Several findings are evident in this analysis. First, there is a selective increase in the expression of oxidative enzymes in circulating leukocytes, with some transcripts displaying striking up-regulation (e.g., CYP2C19) and others exhibiting profoundly reduced expression (e.g., CYP2U1) after injury. Interestingly, POR, the enzyme responsible for synthesizing NADPH required for CYP-mediated oxidation reactions is also up-regulated after injury. Conversely, no changes were observed in expression of either COX1 or COX2. Second, the kinetics of enzyme expression is variable, with some transcripts displaying consistent changes in expression over the 28 day observation period (e.g., CYP2C19), while others were transiently up-regulated (e.g., CYP1B1, ALOX12). Collectively, these findings are consistent with a selective change in expression of oxidative enzymes in circulating leukocytes after trauma.

Figure 1.

Heat Map Analysis of difference in gene expression from peripheral circulating leukocytes in trauma and control subjects. The difference of gene expression is demonstrated by a log 2 scale (i.e., each unit increase indicates a doubling in expression). The shades of green represent downregulation in the trauma subjects from control whereas the shades of red represent upregulation in the trauma subjects from control. The difference in gene expression was evaluated from samples collected Day 0–3, 3–7, 7–14, and 14–28 post traumatic injury.

Top Upregulated and Downregulated Genes

Based upon the results from Fig 1, Table 4 summarizes the ten genes that were the most significantly up-regulated after blunt traumatic injury and Table 5 presents the ten most significantly down-regulated genes. The top five up- or down-regulated genes are further identified by a double check mark. In addition to the distinct pattern of oxidative enzyme regulation, it is interesting to note that both the bradykinin receptor type 1 (BDKRB1) and Type 2 (BDKRB2) are among the top five up-regulated genes at various time points after trauma injury.

Table 4.

Top Ten Upregulated Genes

| Gene | Day 0–3 | Day 3–7 | Day 7–14 | Day14–28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP26A1 | √√ | √√ | √√ | √√ |

| BDKRB1 | √√ | √√ | √√ | √√ |

| CYP2C19 | √√ | √√ | √√ | √√ |

| NOXO1 | √√ | √ | √ | √ |

| CYP4Z2P | √√ | √ | √ | |

| NOS1AP | √ | √√ | √√ | √√ |

| BDKRB2 | √ | √√ | √√ | √√ |

| POR | √ | |||

| ALOX5AP | √ | |||

| ALOX5 | √ | |||

| CYP24A1 | √ | √ | √ | |

| EPHX1 | √ | √ | √ | |

| CYP2D6 | √ | |||

| CYP19A1 | √ | |||

| NCF1 | √ | |||

| CYP2A7 | √ |

Table 5.

Top Ten Downregulated Genes

| Gene | Day 0–3 | Day 3–7 | Day 7–14 | Day14–28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2U1 | √√ | √√ | √√ | √√ |

| CYP2R1 | √√ | √√ | √√ | √√ |

| CYP20A1 | √√ | √√ | √√ | √√ |

| CYP1A2 | √√ | √√ | √√ | √√ |

| CYP27A1 | √√ | |||

| CYP4V2 | √ | √ | √√ | √ |

| EPHX2 | √ | √ | √ | |

| CYP3A5 | √ | √√ | √√ | |

| CYP2C9 | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| CYP2A13 | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| CYP27C1 | √ | √ | √ | |

| EPHX4 | √ | |||

| CYP2B7P1 | √ |

Correlation with Clinical Trauma Scores

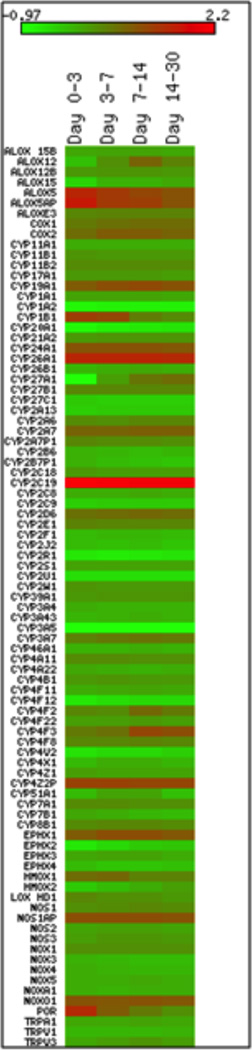

To determine the association between the clinical scores and the most significant up and downregulated genes over time, we used proportional Venn Diagrams as shown in Figures 2A–C. A total of 88 genes were identified that were significantly increased over control expression levels within any time interval with a criterion value of p<0.001; this domain of 88 genes is depicted by the large circle in Figures 2A–C. Figure 2A is a Venn diagram that illustrates the overlap between this domain of 88 genes with genes that were significantly correlated with the APACHE II Scores (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II). The APACHE II score is a clinical ICU score that is applied within 24 hours of patient admission to an intensive care unit (24, 25). Two genes, CYP51A1 and CYP4F3, were significantly up-regulated and correlated with APACHE II scores. A pathway analysis of these genes by www.GeneMania.org indicates that these two genes are highly co-expressed with genes that support sterol biosynthesis (false discovery rate (FDR) = 5.05e−28). Figure 2B compares the domain of 88 significantly changed genes with genes that correlated with the Max Denver 2 score over time. The Denver 2 is a clinical multi-organ failure scoring system that is computed based on the pulmonary, renal, hepatic and cardiac systems (26). There was a common overlap of 5 genes that were significantly changed from control and that correlated with Max Denver scores >2. These 5 genes were CYP19A1, HMOX2, NCF1, NCF2 and PTGER2. The pathway analysis of these genes (www.GeneMania.org) indicates that they are highly co-expressed with genes that provide an oxidative respiratory burst (FDR = 2.49e−9) and superoxide anion generation (FDR = 6.71e−8). Figure 2C compares the overlap between the 88 significantly changed genes and genes that correlated with Injury Severity Score (27) over time with a p-value less than 0.001 as demonstrated by the blue circle. There was a common overlap of 11 genes that were significantly changed from control that also correlated with the Injury Severity Score. These 11 genes are CYP19A1, CYP20A1, CYP2A7, CYP2B7P1, CYP2C19, CYP2E1, CYP4A11, CYP8B1, ESR2 and NOX1. The pathway analysis of these genes indicates that they are highly co-expressed with genes that provide a cellular response to xenobiotic stimulus (FDR = 1.16e−23) and monooxygenase activity (FDR = 2.91e−20).

Figure 2.

A–C. Overlap of genes that exhibited both a significant upregulation of expression in circulating leukocytes (p<0.001; n=88) and were associated with clinical evaluation of trauma as measured by Panel A: APACHE II scores (n=2 genes: CYP51A1 and CYP4F3), Panel B: Max Denver 2 Score (n=5 genes: CYP19A1, HMOX2, NCF1, NCF2 and PTGER2) and Panel C: Injury Severity Score (n=11 genes: CYP19A1, CYP20A1, CYP2A7, CYP2B7P1, CYP2C19, CYP2E1, CYP4A11, CYP8B1, ESR2 and NOX)

DISCUSSION

Oxidized lipids synthesized from linoleic and arachidonic acid are known to be elevated after injury (1–3) or inflammation (11–14). Recent studies have demonstrated that the CYP, LOX and COX enzymes likely mediate oxidation of PUFAs after tissue injury (9, 10, 28). Given the substantial effect of oxidized lipids on hemodynamic, pulmonary, immune and neuronal systems (29–31), it is likely that these lipids play major roles in initiating and integrating pathophysiologic responses to many forms of injury. However, it is not known whether the enzymatic machinery capable of oxidizing these bioactive lipids is up-regulated after major blunt trauma. Here, we present clinical data that this effect is substantial, selective and persists long after the traumatic event. Interestingly, neither COX1 nor COX2 were up-regulated after trauma, suggesting a more dominant role for either CYP or LOX isozymes under these conditions. It is important to note that gene expression does not necessarily correlate to protein or enzyme activation. This study is focused on changes in expression of leukocyte oxidative genes after traumatic injury, and these results could be extended to future proteomic studies.

The existence of a selective alteration in expression of transcripts encoding oxidative enzymes reveals a complex molecular response to major blunt trauma in circulating leukocytes. Evidence for the selectivity of this pattern of genetic changes is based on the finding of highly significant increased, as well as decreased changes in gene expression. Nonetheless, the mechanisms mediating this response are unclear. It can be speculated that endocrine responses to stress and trauma might alter oxidative enzyme expression, although no prior published studies have reported this pattern of transcriptional events. Alternatively, it is possible that trauma itself, via introduction of foreign antigens or altered interactions with damaged cells or extracellular matrices, might lead to the observed changes. These alternatives should be evaluated in subsequent studies. Since the clinical samples consisted of circulating leukocytes, these oxidative enzymes are capable of generating biologically active substances at a systemic level including both vascular and interstitial compartments. The physiologic significance of this finding is supported by the observed association of several of these transcripts with clinical trauma indices. This association provides a novel means for integrating pathophysiologic responses to trauma that is distinct from classical endocrine, paracrine or neuronal forms of signaling.

Evaluation of the time course reveals that many of the sampled transcripts display persistent changes in expression out to the last time point measured, at 28 days. The full time-response curve is undefined, but clearly extends to at least a month after trauma. Persistent changes in gene expression may signify epigenetic mechanisms regulating (32) the expression of these transcripts. If epigenetic mechanisms are involved, it is possible that patients with a prior history of major trauma would be pre-disposed to an altered response to any subsequent traumatic event. These responses could be enhanced or suppressed depending on changes in gene expression and the function of the translated proteins.. Nonetheless, such epigenetic changes may play an important role in patients with a history of poly-trauma related events.

In conclusion, characterizing the molecular responses to trauma is an important and essential step in understanding pathophysiologic responses to injury and in managing the trauma patient. The results provide clinical evidence for a distinct and prolonged pattern of expression of transcripts encoding oxidative enzymes in circulating leukocytes. These findings direct future research into the role of oxidized lipids in integrating pathophysiologic responses to major blunt trauma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support

This study was supported by NIH 5T32GM079085, NCATS 8UL1TR000149, R01NS72890, R01DA019585, the Owens Foundation and the USAA Foundation President’s Distinguished University Chair in Neurosciences (KMH). The investigators acknowledge the contribution of the Inflammation and the Host Response to Injury Large-Scale Collaborative Project Award #2U54GM062119 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Sponsored by the Department of the Army, W81XWH-07-1-0717. The U.S. Army Medical research Acquisition Activity, 820 Chandler Street, Fort Detrick MD 21702-5014 is the awarding and administering acquisition office. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest.

Disclaimer: The Inflammation and the Host Response to Injury “Glue Grant” program is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. This abstract/manuscript was prepared using a dataset obtained from the Glue Grant program and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Inflammation and the Host Response to Injury Investigators or the NIGMS.

References

- 1.Kosaka K, Suzuki K, Hayakawa M, Sugiyama S, Ozawa T. Leukotoxin, a linoleate epoxide: its implication in the late death of patients with extensive burns. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;139(2):141–148. doi: 10.1007/BF01081737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moghaddam MF, Grant DF, Cheek JM, Greene JF, Williamson KC, Hammock BD. Bioactivation of leukotoxins to their toxic diols by epoxide hydrolase. Nat Med. 1997;3(5):562–566. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sisemore MF, Zheng J, Yang JC, Thompson DA, Plopper CG, Cortopassi GA, Hammock BD. Cellular characterization of leukotoxin diol-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;392(1):32–37. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng J, Plopper CG, Lakritz J, Storms DH, Hammock BD. Leukotoxin-diol: a putative toxic mediator involved in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25(4):434–438. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.4.4104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolaou A, Pilkington SM, Rhodes LE. Ultraviolet-radiation induced skin inflammation: dissecting the role of bioactive lipids. Chem Phys Lipids. 2011;164(6):535–543. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhodes LE, Gledhill K, Masoodi M, Haylett AK, Brownrigg M, Thody AJ, Tobin DJ, Nicolaou A. The sunburn response in human skin is characterized by sequential eicosanoid profiles that may mediate its early and late phases. FASEB J. 2009;23(11):3947–3956. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-136077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roszkowski MT, Swift JQ, Hargreaves KM. Effect of NSAID administration on tissue levels of immunoreactive prostaglandin E2, leukotriene B4, and (S)-flurbiprofen following extraction of impacted third molars. Pain. 1997;73(3):339–345. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porter NA, Weber BA, Weenen H, Khan JA. Autoxidation of polyunsaturated lipids. Factors controlling the stereochemistry of product hydroperoxides. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1980;102(17):5597–5601. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruparel S, Green D, Chen P, Hargreaves KM. The cytochrome P450 inhibitor, ketoconazole, inhibits oxidized linoleic acid metabolite-mediated peripheral inflammatory pain. Mol Pain. 2012;8:73. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruparel S, Henry MA, Akopian A, Patil M, Zeldin DC, Roman L, Hargreaves KM. Plasticity of cytochrome P450 isozyme expression in rat trigeminal ganglia neurons during inflammation. Pain. 2012;153(10):2031–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks CJ, Harland WA, Steel G, Gilbert JD. Lipids of human atheroma: isolation of hydroxyoctade cadienoic acids from advanced aortal lesions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;202(3):563–566. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(70)90131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jira W, Spiteller G, Richter A. Increased levels of lipid oxidation products in low density lipoproteins of patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. Chem Phys Lipids. 1997;87(1):81–89. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(97)00030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engels F, Drijver AA, Nijkamp FP. Modulation of the release of 9-hydroxy-octadecadienoic acid and other fatty acid derived mediators from guinea-pig pulmonary macrophages. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1990;12(2):199–205. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(90)90054-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaduce TL, Figard PH, Leifur R, Spector AA. Formation of 9-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid from linoleic acid in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(12):6823–6830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nathens AB, Johnson JL, Minei JP, Moore EE, Shapiro M, Bankey P, Freeman B, Harbrecht BG, Lowry SF, McKinley B, Moore F, West M, Maier RV. Inflammation and the Host Response to Injury, a large-scale collaborative project: Patient-Oriented Research Core--standard operating procedures for clinical care. I. Guidelines for mechanical ventilation of the trauma patient. J Trauma. 2005;59(3):764–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein MB, Silver G, Gamelli RL, Gibran NS, Herndon DN, Hunt JL, Tompkins RG. Inflammation and the host response to injury: an overview of the multicenter study of the genomic and proteomic response to burn injury. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27(4):448–451. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000227477.33877.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cobb JP, Mindrinos MN, Miller-Graziano C, Calvano SE, Baker HV, Xiao W, Laudanski K, Brownstein BH, Elson CM, Hayden DL, Herndon DN, Lowry SF, Maier RV, Schoenfeld DA, Moldawer LL, Davis RW, Tompkins RG, Bankey P, Billiar T, Camp D, Chaudry I, Freeman B, Gamelli R, Gibran N, Harbrecht B, Heagy W, Heimbach D, Horton J, Hunt J, Lederer J, Mannick J, McKinley B, Minei J, Moore E, Moore F, Munford R, Nathens A, O'Keefe G, Purdue G, Rahme L, Remick D, Sailors M, Shapiro M, Silver G, Smith R, Stephanopoulos G, Stormo G, Toner M, Warren S, West M, Wolfe S, Young V. Application of genome-wide expression analysis to human health and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(13):4801–4806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409768102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feezor RJ, Baker HV, Mindrinos M, Hayden D, Tannahill CL, Brownstein BH, Fay A, MacMillan S, Laramie J, Xiao W, Moldawer LL, Cobb JP, Laudanski K, Miller-Graziano CL, Maier RV, Schoenfeld D, Davis RW, Tompkins RG. Whole blood and leukocyte RNA isolation for gene expression analyses. Physiol Genomics. 2004;19(3):247–254. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00020.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warde-Farley D, Donaldson SL, Comes O, Zuberi K, Badrawi R, Chao P, Franz M, Grouios C, Kazi F, Lopes CT, Maitland A, Mostafavi S, Montojo J, Shao Q, Wright G, Bader GD, Morris Q. The GeneMANIA prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server issue):W214–W220. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lange M, Szabo C, Traber DL, Horvath E, Hamahata A, Nakano Y, Traber LD, Cox RA, Schmalstieg FC, Herndon DN, Enkhbaatar P. Time profile of oxidative stress and neutrophil activation in ovine acute lung injury and sepsis. Shock. 2012;37(5):468–472. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31824b1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seitz DH, Perl M, Mangold S, Neddermann A, Braumuller ST, Zhou S, Bachem MG, Huber-Lang MS, Knoferl MW. Pulmonary contusion induces alveolar type 2 epithelial cell apoptosis: role of alveolar macrophages and neutrophils. Shock. 2008;30(5):537–544. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31816a394b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gebhard F, Kelbel MW, Strecker W, Kinzl L, Bruckner UB. Chest trauma and its impact on the release of vasoactive mediators. Shock. 1997;7(5):313–317. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199705000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hohl A, Gullo Jda S, Silva CC, Bertotti MM, Felisberto F, Nunes JC, de Souza B, Petronilho F, Soares FM, Prediger RD, Dal-Pizzol F, Linhares MN, Walz R. Plasma levels of oxidative stress biomarkers and hospital mortality in severe head injury: a multivariate analysis. J Crit Care. 2012;27(5):523, e11–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen HB, Banta JE, Cho TW, Van Ginkel C, Burroughs K, Wittlake WA, Corbett SW. Mortality predictions using current physiologic scoring systems in patients meeting criteria for early goal-directed therapy and the severe sepsis resuscitation bundle. Shock. 2008;30(1):23–28. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181673826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sauaia A, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Ciesla DJ, Biffl WL, Banerjee A. Validation of postinjury multiple organ failure scores. Shock. 2009;31(5):438–447. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31818ba4c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osler T, Rutledge R, Deis J, Bedrick E. ICISS: an international classification of disease-9 based injury severity score. J Trauma. 1996;41(3):380–386. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199609000-00002. discussion 386-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen H, Ostman J, Bubb KJ, Panayiotou C, Priestley JV, Baker MD, Ahluwalia A. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) is a novel activator of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channel. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(17):13868–13876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.334896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keel M, Trentz O. Pathophysiology of polytrauma. Injury. 2005;36(6):691–709. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basu S. Bioactive eicosanoids: role of prostaglandin F(2alpha) and F(2)-isoprostanes in inflammation and oxidative stress related pathology. Mol Cells. 2010;30(5):383–391. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossi A, Pergola C, Cuzzocrea S, Sautebin L. The role of 5-lipoxygenase and leukotrienes in shock and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Scientific World Journal. 2007;7:56–74. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong HR, Freishtat RJ, Monaco M, Odoms K, Shanley TP. Leukocyte subset-derived genomewide expression profiles in pediatric septic shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11(3):349–355. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181c519b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.