Abstract

BACKGROUND

Pediatric massive blood transfusions occur widely at hospitals across the nation; however, there are limited data on pediatric massive transfusion protocols (MTPs) and their impact. We present a pediatric MTP and examine its impact on morbidity and mortality as well as identify factors that may prompt protocol initiation.

METHODS

Using a prospective cohort, we collected data on all pediatric patients who required un–cross-matched blood from January 1, 2009, through January 1, 2011. This captured patients who received blood products according to the protocol as well as patients who were massively transfused at physician discretion. Outcomes between groups were compared.

RESULTS

A total of 55 patients received un–cross-matched blood, with 22 patients in the MTP group and 33 patients receiving blood at physician discretion (non–MTP group). Mortality was not significantly different between groups. Injury Severity Score for the MTP group was 42 versus 25 for the non–MTP group (p ≤ 0.01). Thromboembolic complications occurred more exclusively in the non–MTP group (p ≤ 0.04). Coagulopathy, evidenced by partial thromboplastin time (PTT) greater than 36, was associated with initiation of the MTP.

CONCLUSION

MTPs have been widely adopted by hospitals to minimize the coagulopathy associated with hemorrhage. Blood transfusion via MTP was associated with fewer thromboembolic events. Coagulopathy was associated with initiation of the MTP. These results support the institution of pediatric MTPs and suggest a need for further research on the protective relationship between MTP and thromboembolic events and on identifying objective factors associated with MTP initiation.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE

Therapeutic study, level IV.

Keywords: Pediatric, massive transfusion protocol, thromboembolic events

Massive blood transfusion results from trauma, surgical complications, cardiac surgery, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and other instances that require a large ratio of the patient’s blood volume to be replaced rapidly. Given that physicians from a variety of backgrounds may be involved in the process of the massive blood transfusion, there has been national interest in adopting hospital-wide protocols as a means of minimizing the coagulopathy associated with significant blood loss. These protocols are applicable to a diverse group of physicians including anesthesiologists, emergency medicine physicians, critical care physicians, trauma surgeons, and other specialists. Controversy exists surrounding the proper ratio of blood products that should be used to maximize survival and minimize morbidity in exsanguinating patients.

Based on recent research in the adult population, Nationwide Children’s Hospital has adopted a massive transfusion protocol (MTP) for its pediatric population. Inspired by austere military conditions where whole-blood products are more readily available for transfusion, current research in the civilian population has shown improved outcomes when fresh frozen plasma (FFP) is transfused in a higher ratio with packed red blood cells (PRBCs) and platelets than has been common practice in the past.1,2 Based on this research, transfusing FFP in a one-to-one ratio with PRBCs and/or platelets has been shown to have survival benefits in adult populations.1–5 The coagulopathy of trauma is a well-documented component of the “lethal triad” in which there is a worsening cycle of coagulopathy, hypothermia, and acidosis.6 Hypothermia in trauma patients is the result of shock, exposure, and large-volume resuscitation using room temperature fluids, which decreases platelet activation and adhesion.6–8 Hemodilution, caused by the infusion of crystalloid solutions or PRBC units without sufficient co-infusion of FFP and platelet, dilutes clotting factors and also worsens hypothermia. Acidosis resulting from shock further inhibits proper clotting factor function and leads to worsening coagulopathy. MTPs have been adopted across the United States and internationally to minimize the effects of the lethal triad.9 Pediatric massive transfusion differs from adult massive transfusion because children are better able to tolerate blood loss owing to their relatively substantial physiologic reserve. Thus, pediatric massive transfusion may require a greater percentage of overall blood loss to initiate massive transfusion, based on previous research that defines abnormal vital sign ranges associated with MTP initiation.7,10,11 There is limited research on massive blood transfusion in the pediatric population. As such, our objective was to examine the impact of this protocol on morbidity and mortality in our pediatric population. Our primary outcome was mortality. We also examined the impact of the MTP on the amount of blood product consumed, the amount of crystalloid used, thromboembolic events, and the use of factor VIIa. We also attempted to identify variables that should prompt the initiation of the MTP in our population, including coagulopathy and anemia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Protocol Design

Massive transfusion in the pediatric population was defined as the transfusion of blood components equaling one or more blood volumes within a 24-hour time frame or half of a blood volume in 12 hours. The definition of pediatric massive transfusion is empiric based on a review of blood use patterns at our hospital. Generally accepted blood volume conversion factors are 100 mL/kg for premature neonates, 90 mL/kg for mature neonates, 80 mL/kg for infants and 70 mL/kg to 80 mL/kg for older children.12,13 In older, adult-sized children, massive transfusion was defined as greater than 10 U of PRBCs in 24 hours.13

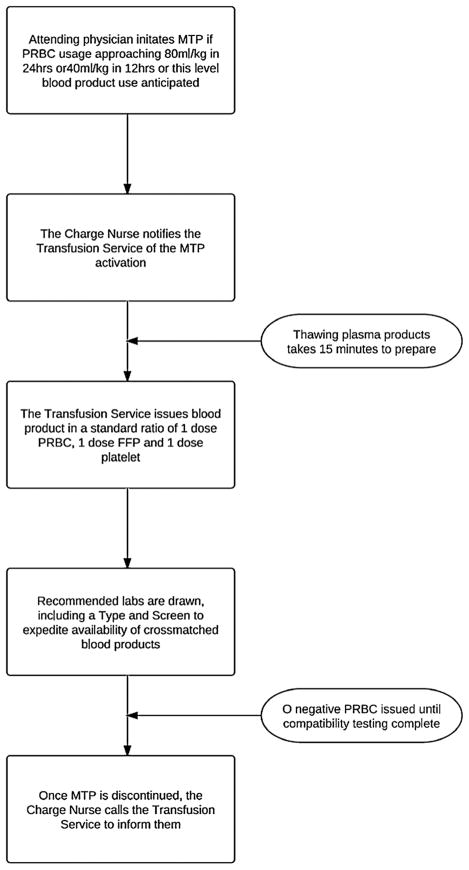

The MTP was adopted at this institution in September 2008, based on military and adult civilian data, which supported use of an MTP through improved patient outcomes. The protocol was designed to minimize coagulopathy for pediatric trauma patients or any pediatric patient with massive bleeding. The protocol can be activated from any critical care area, including operating rooms, the emergency department, or pediatric intensive care units (Fig. 1). Therapeutic goals included maintaining platelet count of greater than 50,000 and hemoglobin level of higher than 10 mg/dL and achieving normalization of coagulation assays. A recommended panel of laboratory studies was developed to guide these practices at various points throughout the MTP (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Process flow for massive transfusion protocol.

TABLE 1.

Recommended Laboratory Studies for the Hemorrhaging Patient Receiving a Massive Transfusion

| Initial | After First 80-mL/kg RBCs | Every 40-mL/kg RBCs Thereafter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | X | X | X |

| Platelet count | X | X | X |

| Prothrombin time | X | X | X |

| Partial thromboplastin time | X | X | X |

| Fibrinogen | X | X | X |

| Fibrin degradation products | X | X | |

| Calcium | X | X | |

| Potassium | X | X | X |

| pH | X | X | X |

| Lactate | X |

Patient Selection

This protocol received institutional review board approval at Nationwide Children’s Hospital (IRB-09-00338). Nationwide Children’s Hospital is a freestanding pediatric Level I trauma center with approximately 1,500 trauma admissions per year. Patients were prospectively enrolled in our study from January 1, 2009, through January 1, 2011. This period was selected with the intent to allow several unstudied months for familiarization with the new protocol and with the goal of enrolling 50 total patients, based on the amount of patients requiring un–cross-matched blood in 2008. Any patient who received a transfusion of un–cross-matched blood was entered into our database. These patients were identified from blood bank records, which track all blood product use throughout the hospital. All patients who received un–cross-matched blood were selected for the study.

Although Nationwide Children’s Hospital serves a pediatric population (<21 years), older patients occasionally self-transport to the emergency department. In our study, patient age ranged from 3 weeks to 28 years. There were two patients older than 21 years. These patients, age 23 years and 28 years, presented as “walk-ins” after sustaining gunshot wounds. One patient was included in the MTP group, and the other was included in the non–MTP group. Because the MTP could only be activated at the physician’s discretion, not all patients who required massive blood transfusion received blood according to the MTP. It was assumed that analyzing all un–cross-matched blood use would capture all trauma patients or surgical bleeding complications that were likely to require massive transfusion.

The blood bank also keeps records of all MTP activations. Thus, we were able to capture and verify all MTP activations through our database of un–cross-matched blood product use. Patients who received un–cross-matched blood but were not MTP activations were grouped into the non–MTP group. All patients who received un–cross-matched blood were selected for the study. One patient in the non–MTP group was excluded owing to incomplete data. As a prospective chart review, patient or family consent was not required.

Data points were collected on demographic information (age, race, and sex), time of presentation, mechanism of injury or surgical bleeding as the cause of hemorrhage, thromboembolic events, use of factor VIIa and mortality. The amount of crystalloid, cross-matched and un–cross-matched PRBC, platelet, and FFP units transfused were also recorded. Level of anemia and coagulopathy were tracked via PT/PTT and Hgb/Hct. The 55 patients who received un–cross-matched blood were assigned to MTP (n = 22) or non–MTP (n = 33) groups and included in the statistical analysis. The non–MTP group served as the comparison group for the patients transfused via the MTP protocol. All patients were followed through their hospital admission.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.2 software. χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used for comparisons of categorical data. t test analysis was used for comparisons of thromboembolic data. Data distribution was more adequately assessed through t test owing to the small sample size. Wilcoxon two-sample test was used to analyze the ratio of PRBC/FFP that was transfused. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a value of p ≤ 0.05 was set as a significant value. Logistic regression was used to analyze factors associated with MTP initiation.

RESULTS

A total of 55 patients were enrolled in the study, 22 in the MTP group and 33 in the non–MTP group. Of the patients, 8 were surgical (6 in MTP and 2 in non–MTP group) and 47 were traumatic (16 in MTP and 31 in non–MTP group). One patient was excluded from the non–MTP group owing to incomplete data. The MTP group was not statistically significantly different from the non–MTP group regarding sex, race, or age. Overall, male sex was more common, with 78% male patients and 21% female patients. Mean (SD) age at the time of transfusion was 9.6 (7.2) years. The time of the day at which the transfusion occurred was not significantly different between the groups.

MTP Group Versus Non–MTP Group

The MTP group was likely to be more severely injured than the non–MTP group, with 16 trauma patients in the MTP group and 31 trauma patients in the non–MTP group. The Injury Severity Score for the trauma patients in the MTP group was 42 versus 25 for the trauma patients in the non–MTP group (p ≤ 0.01). Mechanism of injury was more likely to be surgical complication in the MTP group, while blunt and penetrating trauma did not differ significantly between the two groups as mechanisms of injury.

The MTP group also consumed a higher overall amount of blood products, including FFP, PRBC, and platelets (p ≤ 0.0003). The mean blood products consumed per patient were 3 U of un–cross-matched PRBC, 6 U of cross-matched PRBC, 4 U of FFP, and 2 U of platelets in the MTP group, versus 1.6 U of un–cross-matched PRBC, 1.5 U of cross-matched PRBC, 1.2 U of FFP, and 0.4 U of platelets in the non–MTP group. There was no significant difference in the transfused FFP/PRBC ratio between MTP and non–MTP groups. The mean FFP/PRBC ratio was 1:3.

The amount of crystalloid resuscitation attempted before blood transfusion was similar across the two groups. The mean volume of crystalloid infusion was 2,158 mL per patient in the non–MTP group and 2,716 mL per patient in the MTP group. In addition, the level of anemia, as measured by hemoglobin level lower than 11 g/dL on presentation, was similar between the groups. Coagulopathy, as evidenced by PTT greater than 36 seconds, was associated with initiation of the MTP. These levels corresponded to predetermined abnormal values as set by our laboratory.

Mortality was not significantly different between groups, with the mortality rate of 45% in each group. Thromboembolic complications, however, occurred more frequently in the non– MTP group (p ≤ 0.04). A total of 4 thromboembolic complications were identified in our study (12%). All occurred within the non–MTP group (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Patients Who Experienced Thromboembolic Events

| Age, y | Location of Thrombus | Mechanism of Injury | Mortality | Total Blood Product, U |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | Cephalic vein thrombus | Blunt trauma | Alive | 2 PRBC, 0 FFP, 0 platelet |

| 10 | Right common carotid artery and right internal carotid artery | Tracheo-innominate fistula | Alive | 1 PRBC, 0 FFP, 0 platelet |

| 16 | Right common femoral vein | Blunt trauma | Alive | 2 RBC, 1 FFP, 0 platelet |

| 10 | Left brachiocephalic vein; left basilic vein | Blunt trauma | Died | 1 RBC, 0 FFP, 0 platelet |

Recombinant Factor VIIa

Factor VIIa is not part of the MTP and could be given at physician discretion. A total of 11 patients received factor VIIa; 5 in the non–MTP group and 6 in the MTP group. Factor VIIa use was highly correlated to higher blood product consumption, with patients receiving a mean of 5 U of PRBC, 2 U of FFP, and 1 U of platelets (p ≤ 0.0001). There was no significant impact on mortality. No thromboembolic events occurred in these 11 patients.

DISCUSSION

While MTPs designed for the pediatric population have emerged relatively recently, the practice of using reconstituted whole blood is not a new practice. Management of various conditions, including exchange transfusion, cardiopulmonary bypass, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, use reconstituted whole blood.14 In addition, one burn center reports routine use of reconstituted whole blood for blood replacement, with more than a decade of experience and no incidence of sepsis or pulmonary dysfunction in their pediatric population.15 It was expected that transfusion of blood product in an FFP/PRBC ratio of 1:1 would result in improved outcomes because this ratio more closely resembles whole blood.

It was the intent of the MTP at our institution to transfuse in an FFP/PRBC ratio of 1:1; however, the actual transfusion ratio was closer to an FFP/PRBC ratio of 1:3. This may be caused by the delay in obtaining thawed FFP and the availability of rapidly warmed PRBC units in the trauma bay. Given that children require a smaller number of PRBC units to constitute a massive transfusion, it is possible that a significant amount of weight-based PRBCs have been transfused by the time FFP is available. The issue of determining an optimal FFP/PRBC transfusion ratio in children is made difficult by lack of evidence to support a particular ratio in this population. Several studies have attempted to examine this issue but were unable to draw definitive conclusions.16,17 Data in the adult population have shown decreased mortality with high FFP/PRBC ratios;1–5 however, one study in the pediatric population has documented an increased incidence of multiorgan system failure with increasing units of FFP transfused in pediatric liver transplant patients.18

Although there was no difference in mortality between the MTP group and the non–MTP group, thromboembolic events were significantly higher in the non–MTP group. Given the relative rarity of thromboembolic events in pediatric trauma patients, it is notable that 12% of the non–MTP group developed this complication during their hospital stay.19,20

It is difficult to attribute this to a single aspect of the MTP because both groups received similar amounts of crystalloid and were transfused FFP/PRBC in a similar ratio. In addition, the MTP group received a greater overall amount of blood products and was more likely to be severely injured, which should have predisposed them to increased thromboembolic events. Because all patients with a thromboembolic event received 2 U of PRBCs or less and none received blood according to the FFP/PRBC ratio of 1:1, it is possible that the patients were undertransfused, leading to coagulopathy and thromboembolic events. Further research on MTP in the pediatric population is warranted to determine what factors contributed to the absence of thromboembolic events in the MTP group compared with the elevated incidence in the non–MTP group.

Objective data to determine the need for MTP initiation are another area of ongoing research. Studies in the adult population have shown correlation to vital signs and mechanism of injury as predictors of massive transfusion requirements.7,10,11 Initial vital signs may not be good predictors of early hemorrhage in the pediatric population owing to their relatively substantial physiologic reserve. In our population, blunt versus penetrating trauma was not shown to be predictive of MTP initiation. However, early coagulopathy was significantly associated with MTP activation. However, whereas bleeding in an uncontrolled trauma setting predisposes the patient to the lethal triad via rapid blood loss, hypothermia, and acidosis, resulting in coagulopathy, bleeding in a controlled surgical setting where patient temperature and acidosis can be regulated may require separate markers to predict massive blood loss. Additional research is needed to identify other markers that can predict the need for MTP activation.

Factor VIIa was not part of the MTP and was given at the attending physician’s discretion. Studies in the adult population have documented decreased blood product requirements,21–23 but no change in mortality with factor VIIa for trauma patients.21 Pediatric studies have shown factor VIIa to be effective in controlling hemorrhage owing to trauma or surgical complication with low incidence of thromboembolic events.24,25 Our patients received factor VIIa equally as part of the MTP and non–MTP groups. Factor VIIa administration was associated with higher blood product consumption and had no effect on mortality. There were no thromboembolic events for the patients receiving factor VIIa in our study. Limitations of our study include the prospective cohort design. Adoption of an MTP results in systems changes, as another study in the pediatric population noted that their MTP led to a median fourfold decrease in length of time to FFP transfusion.16 We chose this study design because comparing concurrent populations facilitated the accurate capture of differences that resulted from patients receiving blood via MTP and not systems changes that resulted from adoption of an MTP. Given that the protocol was activated at physician discretion, there is inherent selection bias into the MTP; however, blinding physicians in this capacity was not feasible. We also may have failed to evaluate massive transfusions for patients whose Rh factor and antibody data were known, resulting in massive transfusion with exclusively cross-matched blood product.

The benefits of the MTP may extend beyond the hemorrhaging child. During the study period, there were two incidences where the MTP affected the viability of organ donation. One pediatric trauma patient with nonsurvivable injuries did not receive blood products according to the MTP and was ultimately rejected as an organ donor owing to severe hemodilution. Another pediatric trauma patient with injuries incompatible with life required massive blood transfusion to maintain viability of the patient’s organs. Ultimately, four organs in addition to heart valves, skin, and long bones were harvested for transplantation.

CONCLUSION

MTPs have been widely adopted by hospitals in attempt to minimize coagulopathy associated with hemorrhage. This study found that blood transfusion via an MTP is associated with fewer thromboembolic events in the pediatric population. Coagulopathy was a predictor of MTP activation. Factor VII had no effect on mortality and was correlated with higher blood product use. Further research in this area is vital given the breadth of massive transfusion that occurs across the nation in hospitals of different sizes and structures. Research should be directed toward identifying optimal ratios of blood product transfusion, the relationship of thromboembolism to MTP, and the identification of objective factors to predict MTP activation.

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP

S.J.C. and J.I.G. designed this study and collected data. S.J.C. conducted the literature search. S.J.C., N.W., and W.W. analyzed the data, which S.J.C., N.W., and J.I.G. interpreted. S.J.C. and J.I.G. wrote the manuscript, for which S.J.C. prepared figures.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sperry JL, Ochoa JB, Gunn SR, et al. An FFP:PRBC transfusion ratio >1:1.5 is associated with a lower risk of mortality after massive transfusion. J Trauma. 2008;65:986–993. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181878028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duchesne JC, Hunt JP, Wahl G, Marr AB, Wang YZ, Weintraub SE, Wright MJ, McSwain NE., Jr Review of current blood transfusion strategies in a mature Level 1 trauma center: were we wrong for the last 60 years? J Trauma. 2008;65:272–276. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817e5166. discussion 276–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunter OL, Au BK, Isbell JM, et al. Optimizing outcomes in damage control resuscitation: identifying blood product ratios associated with improved survival. J Trauma. 2008;65:527–532. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181826ddf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dente CJ, et al. Improvements in early mortality and coagulopathy are sustained better in patients with blunt trauma after institution of a massive transfusion protocol in a civilian Level I Trauma Center. J Trauma. 2009;66:1616–1623. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a59ad5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotton BA, Gunter OL, Isbell J, Au BK, Robertson AM, Morris JA, JR, St Jacques P, Young PP. Damage control hematology: the impact of a trauma exsanguination protocol on survival and blood product utilization. J Trauma. 2008;64:1177–1182. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31816c5c80. discussion 1182–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraga GP, Bansal V, Coimbra R. Transfusion of blood products in trauma: an update. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larson CR, White CE, Spinella PC, Jones JA, Holcomb JB, Blackbourne LH, Wade CE. Association of shock, coagulopathy, and initial vital signs with massive transfusion in combat casualties. J Trauma. 2010;69(Suppl 1):S26–S32. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e423f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niles SE, McLaughlin DF, Perkins JG, Wade CE, Li Y, Spinella PC, Holcomb JB. Increased mortality associated with the early coagulopathy of trauma in combat casualties. J Trauma. 2008;64:1459–1463. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318174e8bc. discussion 1463–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoyt DB, Dutton RP, Hauser CJ, et al. Management of coagulopathy in the patients with multiple injuries: results from an international survey of clinical practice. J Trauma. 2008;65:755–765. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318185fa9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaughlin DF, Niles SE, Salinas J, Perkins JG, Cox ED, Wade CE, Holcomb JB. A predictive model for massive transfusion in combat casualty. J Trauma. 2008;64(Suppl 2):S57–S63. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318160a566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cotton BA, Dossett LA, Haut ER, Shafi S, Nunez TC, Au BK, Zaydfudim V, Johnston M, Arbogast P, Young PP. Multicenter validation of a simplified score to predict massive transfusion in trauma. J Trauma. 2010;69(Suppl 1):S33–S39. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e42411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downes K, Sarode R. Massive blood transfusion. Indian J Pediatr. 2001;68:145–149. doi: 10.1007/BF02722034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massive Transfusion Protocol. Nationwide Children’s Hospital, General Procedure; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang T. Transfusion therapy in critically ill children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2008;49:5–12. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(08)60004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barret JP, Desai MH, Herndon DN. Massive transfusion of reconstituted whole blood is well tolerated in pediatric burn surgery. J Trauma. 1999;47:526–528. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199909000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendrickson JE, Shaz BH, Pereira G, Parker PM, Jessup P, Atwell F, Polstra B, Atkins E, Johnson KK, Bao G, et al. Implementation of a pediatric trauma massive transfusion protocol: one institution’s experience. Transfusion. 2012;52:1228–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dressler AM, Finck CM, Carroll CL, Bonanni CC, Spinella PC. Use of a massive transfusion protocol with hemostatic resuscitation for severe intraoperative bleeding in a child. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1530–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feickert HJ, Schepers AK, Rodeck B, Geerlings H, Hoyer PF. Incidence, impact on survival, and risk factors for multi-organ system failure in children following liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2001;5:266–273. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3046.2001.005004266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azu MC, McCormack JE, Scriven RJ, Brebbia JS, Shapiro MJ, Lee TK. Venous thromboembolic events in pediatric trauma patients: is prophylaxis necessary? J Trauma. 2005;59:1345–1349. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196008.48461.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanson SJ, Punzalan RC, Greenup RA, Liu H, Sato TT, Havens PL. Incidence and risk factors for venous thromboembolism in critically ill children after trauma. J Trauma. 2010;68:52–56. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a74652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hauser CJ, Boffard K, Dutton R, Bernard GR, Croce MA, Holcomb JB, Leppaniemi A, Parr M, Vincent JL, Tortella BJ, et al. CONTROL Study Group. Results of the CONTROL trial: efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII in the management of refractory traumatic hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2010;69:489–500. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181edf36e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wade CE, Eastridge BJ, Jones JA, West SA, Spinella PC, Perkins JG, Dubick MA, Blackbourne LH, Holcomb JB. Use of recombinant factor VIIa in US military casualties for a five-year period. J Trauma. 2010;69:353–359. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e49059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spinella PC, Perkins JG, McLaughlin DF, Niles SE, Grathwohl KW, Beekley AC, Salinas J, Mehta S, Wade CE, Holcomb JB. The effect of recombinant activated factor VII on mortality in combat-related casualties with severe trauma and massive transfusion. J Trauma. 2008;64:286–293. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318162759f. discussion 293–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herbertson M, Kenet G. Applicability and safety of recombinant activated factor VII to control non-haemophilic haemorrhage: investigational experience in 265 children. Haemophilia. 2008;14:753–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chuansumrit A, Teeraratkul S, Wanichkul S, Treepongkaruna S, Sirachainan N, Pakakasama S, Nuntnarumit P, Hongeng S rFVIIa Study Group. Recombinant-activated factor VII for control and prevention of hemorrhage in nonhemophilic pediatric patients. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2010;21:354–362. doi: 10.1097/mbc.0b013e3283389500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]