Abstract

Background:

‘What is the ideal way of teaching Ayurveda?’ – has been a debated question since long. The present graduate level curriculum lists out the topics from ‘contemporary medical science’ and ‘Ayurveda’ discretely, placing no emphasis on integration. Most of the textbooks, too, follow the same pattern. This makes learning not only difficult, but also leads to cognitive dissonance.

Objectives:

To develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a few integrative teaching methods.

Materials and Methods:

We introduced three different interventions in the subject Kriya Sharira with special reference to ‘cardiovascular physiology’. The instructional methods that we evaluated were: 1. Integrative module on cardiovascular physiology (IMCP), 2. case-stimulated learning (CSL), and 3. classroom small group discussion (CSGD). In the first two experiments, we subjected the experimental group of graduate students to the integrative instructional methods. The control group of students received the instructions in a conventional, didactic, teacher-centric way. After the experiments were over, the learning outcome was assessed and compared on the basis of the test scores. The groups were crossed over thereafter and the instructional methods were interchanged. Finally, feedback was obtained on different questionnaires. In the third experiment, only student feedback was taken as we could not have a control group.

Results:

The test results in the first experiment showed that the integrative method is comparable with the conventional method. In the second experiment, the test results showed that the integrative method is better than the conventional method. The student feedback showed that all the three methods were perceived to be more interesting than the conventional one.

Conclusion:

The study shows that the development of testable integrative teaching methods is possible in the context of Ayurveda education. It also shows that students find integrative approaches more interesting than the conventional method.

Keywords: Ayurveda education, case-stimulated learning, classroom small group discussion, Kriya Sharira, instructional methods, integrative module

INTRODUCTION

The quality of Ayurveda education in post-independence India has been a matter of concern since long and has attracted criticisms of various kinds. Inadequate exposure to basic clinical skills, poorly structured curriculum, mushroom growth of sub-standard colleges, lack of innovation in the faculty development programs, and, ambiguities in the policies on integration - are a few points among others- that have been raised from time to time to suggest that the quality of Ayurveda training is poor.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7] In 2008, a nationwide survey that included interns, postgraduate students and teachers from more than 30 Ayurveda institutions spread across 18 states of India, showed that the ‘teaching methodology’ was one of the crucial areas that needed instant attention.[8,9,10] The study also observed that teaching and learning in Ayurveda education institutions was more ‘memory-oriented’ than ‘understanding- and application-oriented’ in general, along with being teacher-centric. The study also recommended that newer methods of active learning such as ‘problem-based learning’ be incorporated in Ayurveda education.

Though, at present, several topics from contemporary medical science (‘modern medicine’) are included in the syllabi of graduate program of Ayurveda, no specific thrust has been placed on ‘integrating’ the two sciences. The curriculum prescribed by Central Council of Indian Medicine (CCIM) lists out the topics from the two different streams of science under different papers and sections discretely. As Wujastyk puts it, “the two sciences have different epistemological basis and the curriculum continues to inculcate this epistemological split.”[11] This split is especially obvious with the subjects such as anatomy and physiology. This in fact, poses a threat: Students go for ‘rote learning’, and thus miss the links between the two sciences and the links between ‘theory’ and ‘application’ leading to a state of cognitive dissonance. In 1958, Udupa committee on “Ayurveda Research Evaluation” strongly recommended that ‘the delivery of relevant contents from contemporary medical physiology and anatomy to explain away the gaps left in Ayurveda’ was necessary.[1] After this, several committees and individual educationists have been arguing in favor of developing an integrative curriculum for Ayurveda education.[12]

Considering these facts, we planned the present study, where, we developed a few integrative teaching methods and evaluated their efficiency in graduate level of Ayurveda education. We restricted our inquiry to the field of Kriya Sharira (Ayurveda physiology) as this is a vital subject that introduces the recent understandings in human physiology along with the classical Ayurveda descriptions. It is also a subject that forms the foundation of clinical pathology, highlighting the applicability of various theories and principles in clinical setup.

Objectives of the study

To develop a few integrative methods of teaching with a view of enhancing the quality of learning experience in Kriya Sharira at graduate level of Ayurveda education

To compare the learning outcomes of these integrative methods with the conventional teaching method that lays almost no emphasis on integration.

Definition of the phrase ‘integrative methods of instruction’

The meaning of ‘integrative approaches’ in the context of Ayurveda education is considerably different from the generally understood ‘integration’ in other fields of education. This is primarily because the so called ‘epistemological split’ does not come into picture in other fields, whereas, it is the most important factor that makes many scholars believe that a true ‘integration’ is not possible between Ayurveda and contemporary biomedicine.[13,14,15] Therefore, for the purpose of this study, we had to define the phrase ‘integrative methods of instruction’ and we defined it as follows:

The instructional methods that help in bridging the gaps between the two streams of sciences, that is, ‘Ayurveda physiology’ and ‘contemporary biomedical physiology’

The instructional methods that help in integrating the theoretical knowledge with the clinically relevant application

The instructional methods that help in understanding the links between different organ systems and Dosha-Dhatu-Mala highlighting their role in maintaining the homeostasis.

In this study, we report the results of three experiments, where, we employed different instructional methods to emphasize the integrative way of understanding the subject. In the first experiment [integrative module on cardiovascular physiology (IMCP)], the experimental group of students was subjected to a well-planned teaching module that incorporated the descriptions from Ayurveda texts along with the relevant information from the field of contemporary medical physiology in an integrative fashion. Development of such ‘integrative modules’ or ‘cross-curricular units’ is a known way of achieving integration, which eventually paves way to the development of a full-fledged integrated curriculum.[16,17] In the second experiment [case-stimulated learning (CSL)], the experimental group of students was exposed to CSL, which is a derivative form of the classical problem-based learning.[18,19] In the third experiment, we incorporated ‘classroom small group discussion’ (CSGD), in which, the students were split into small groups and instructions were carried out in the form of guided group discussions where the process of active learning was emphasized.[20,21,22,23,24] Integrative explanation was the key feature in all the three experiments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The approval from the institutional ethics committee was obtained before starting with the experiments. Later, the relevant Ayurveda, Vedic, and contemporary literature related to the topic of present study was scanned thoroughly. Authentic portions from Ayurveda compendia along with the views of various commentators were screened. For the purpose of collecting the contemporary literature, the relevant textbooks, journal articles, and various authentic websites were consulted.[25,26] In continuum, an effort was also made to interpret the classical explanation in terms of contemporary medical physiology. The material was then rearranged so as to plan the experiments meticulously.

Population

Population for the present study was defined in terms of the students who were registered in the first professional Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine and Surgery (BAMS) program conducted in our institution for the academic years 2011-2012 and 2012-2013.

Sampling and randomization

Students of both the academic years were randomized and grouped separately into two equal groups: ‘Experimental’ and ‘control’. We used the = RAND() function available with Microsoft Excel 2007 workbook for this purpose. During the session 2011-2012, two students were dropped out of the first experiment because they opted out of the BAMS program. In second and third experiments, two more students were dropped out because of the same reason.

Experiments

The first author of this report was the instructor for all the three experiments. All the experiments were conducted in the presence and direct supervision of the senior author.

IMCP

First stage: ‘Discrete’ and ‘Integrative’ teaching

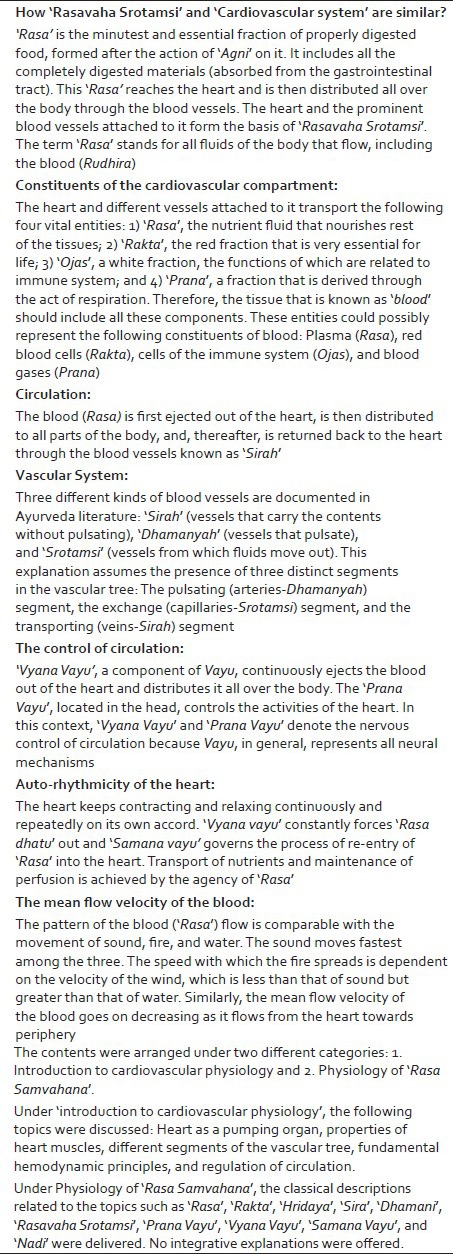

“An introduction to cardiovascular physiology” was the title of the module that was evaluated in this experiment. In this method, the experiment was done to compare the effectiveness of ‘discrete’ and ‘integrative’ teaching methods. We borrowed the term ‘discrete’ from the phrase ‘discrete subject teaching’, a well-known method used in the context of primary education.[27] We decided to use this term to highlight the position of ‘detachment’ while viewing the two streams of science. In this method, Ayurveda and contemporary biomedicine portion of the topic was delivered without discussing any correlation or integration. This is how usually teaching takes place in most of the Ayurveda education institutions. The control group received instructions in this conventional way, but the experimental group was introduced to a new way of instruction, that is, integrative method. In this method, the concepts of Ayurveda and contemporary medical science were correlated using the ideas derived from different sources of scholarly literature authored by various contemporary scholars.[28,29,30,31,32] Box-1 shows the summary of the content that was covered in two different methods of teaching.

Box-1.

Summary of the method in which the subject content was arranged and delivered under ‘Integrative Module’

Two sets of power-point presentations were prepared for the control group and the experimental group separately. Care was taken to follow all the guidelines for effective presentations in both the cases (for instance, each slide had less than six rows and each row contained no more than seven words). Care was also taken to cover all the topics with equal details for both the groups so that no group missed out on any vital piece of information. Duration of each teaching session was 1 hour. In total, both the groups received instructions for 5 hours each.

Assessment of the learning outcome

The learning outcome was assessed in the form of a short written test of 1 hour duration conducted after the completion of the first stage of the experiment. The paper included subjective (13 questions) and objective (six questions) types of questions along with one question to assess the critical thinking ability. Each answer was awarded with the marks that varied from zero to one depending on the extent of understanding reflected in the answers based on a predetermined protocol. Box-2 shows the sample questions from the test paper.

Box-2.

IMCP: Sample questions that were incorporated in the written test conducted after the completion of the first stage

Second Stage: Crossing over

After the completion of the test, as a part of the second stage of the experiment, both groups were crossed over, during which, the teaching methodologies were interchanged.

CSL

First stage

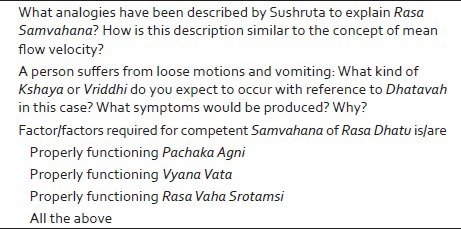

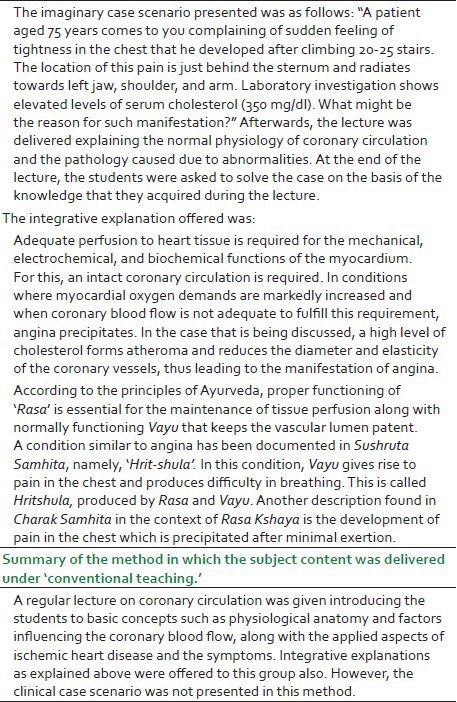

This experiment was designed with an aim of achieving integration between ‘theory’ and ‘application’ along with achieving ‘Ayurveda-Biomedicine’ integration. This was done by incorporating CSL sessions into the conventional lecture. “Physiology of coronary circulation” was selected as the topic for the experiment. The students were first introduced to an imaginary clinical case scenario. A brief history of the patient, symptoms, and investigation reports were provided, and thereafter, the physiology was described in a conventional manner. At the end of the lecture, the case was taken up once again and the students were asked to solve the mystery of the case. Based on the student responses, the explanations on physiological aspects were provided. Thus, the students went through the normal physiology, also being simultaneously exposed to the application aspect. Two power point presentations were prepared: One for the control group and the other for the experimental group. The control group of students received the information in a conventional way in which the ‘clinical problem’ was not discussed, though the integrative explanations were offered. Box-3 shows the subject content that was covered for two groups of the students.

Box-3.

Summary of the method in which the content under ‘Case-Stimulated Learning’ was delivered

Assessment of the learning outcome

The learning outcome was assessed in the form of a short written test of 30 min duration conducted after the completion of the first stage of the experiment. The paper included 15 objective types of questions each with a single correct answer. Each correct answer carried one mark.

Second stage: Crossing over

After the completion of the written test, the groups were crossed over, during which the teaching methods were interchanged.

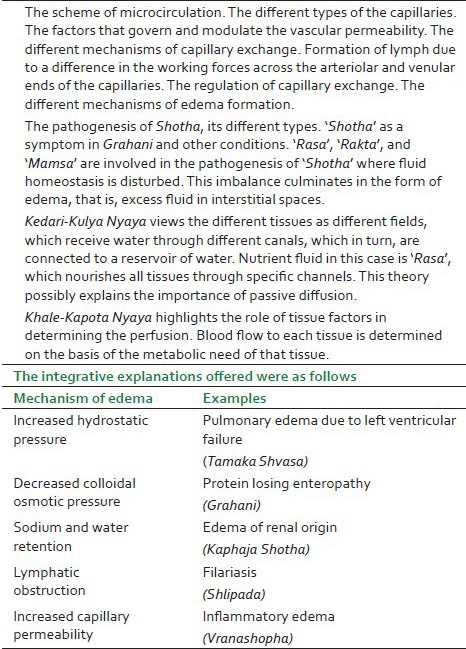

CSGD

In this method, the experiment was done to evaluate the effectiveness of closely monitored ‘group study’ and discussions. For this purpose, the students were distributed into multiple groups comprising of about 6 students each. They were then assigned a topic and were provided with the reference material in the form of textbooks and review articles. “Microcirculation and edema” was selected as the topic for this experiment. Students were asked to study, understand and discuss the topic for 1 hour within the group. The instructor acted as a facilitator and helped students in studying and understanding the physiological principles regulating the microcirculation, while also introducing them to the integrative way of understanding the concepts of ‘Edema’ and ‘shotha’.

As we had multiple groups that were exposed to ‘small group discussion’ type of study, we could not have a control group in this experiment. Further, we did not go for a written test because there was no group to compare the learning outcome with. Therefore, we had to rely upon the feedback that we received in response to the questionnaire that we distributed. Box-4 covers the summary of the content that was discussed.

Box-4.

Summary of the content that was distributed on which the small group discussion was based:

Feedback from the learners

After the completion of each experiment, the feedback was obtained from the students. This feedback was in the form of questionnaires consisting of eight to ten statements. All the statements demanded students‘ level of agreement on a five-point Likert scale. Half of the statements in each questionnaire were just the reverse of the rest. This was to make sure that the students expressed their opinions only after giving their thoughts carefully to the items. The five levels of agreement were: ‘strongly agree’, agree’, ‘undecided’, ‘disagree’, and ‘strongly disagree’. The five-point scale was so adjusted that a score of 1 would mean a strong agreement in favor of the integrative method and a score of 5 would mean a strong agreement against the integrative method of teaching. During the analysis, a mean score lesser than 3 was considered to be indicative of the agreement in favor of the integrative method and a mean score greater than 3 was considered to be indicative of an agreement against the integrative method of teaching.

Reliability and consistency of the feedback forms

As described earlier, the students were asked to complete the learners’ feedback forms after the completion of each experiment. A reliability test in the form of Cronbach's coefficient alpha was carried out in all the instances. This was done to find out the correlation between the respective item and the total sum score (without the respective item) and the internal consistency of the scale (coefficient alpha) if the respective item would be deleted. While validating the scale, value of alpha greater than 0.7 was considered acceptable[33] and item-total correlation greater than 0.2 was considered acceptable.[34] Though we conducted this reliability test after obtaining the filled-in scale, the analysis shows that all the three questionnaires were reliable and consistent.

It is to be noted that while applying all the statistical tests, students of the two academic sessions were added up and were considered to be a single entity under each group.

RESULTS

IMCP

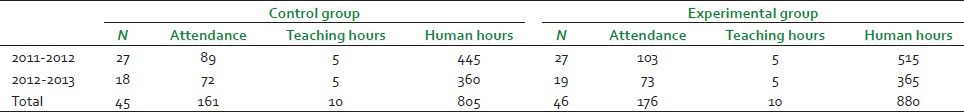

Table 1 shows the number of students assigned to each group and the total number of human hours spent (human hours = total hours of attendance multiplied by the total number of teaching hours) during each session. As depicted in this table, the maximum number of human hours, which indicates the attendance pattern of the students, was documented in the experimental group. This is indicative of the fact that the experimental group found the experiment to be more interesting than the conventional teaching method.

Table 1.

The attendance, teaching hours, and human hours spent during the first experiment (Integrative module on cardiovascular physiology)

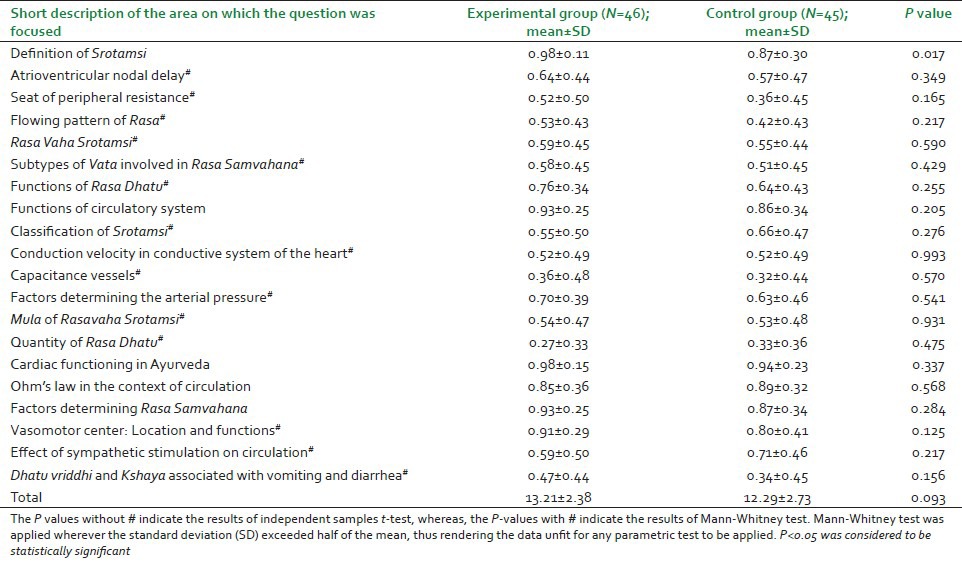

Table 2 depicts the mean scores obtained by the different groups of students after undergoing the written test. As the table suggests, the difference between the mean scores obtained by the two groups was statistically significant for only one question, that is, Q1 (mean scores for experimental group = 0.98 ± 0.11, mean scores for control group = 0.87 ± 0.30, P = 0.017). For the rest of the questions, the difference in the mean scores was not significant. This means that the overall difference in the performance between the two groups was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

The groupwise results of the written test for first experiment (Integrative module on cardiovascular physiology)

On analyzing the feedback, we noticed that the respondents recorded a strong agreement in favor of the integrative teaching method (mean score 1.41 ± 0.84). They also felt the integrative method made the links between Ayurveda and contemporary physiology easy to understand (mean score 1.30 ± 0.51) and made Ayurveda concepts relevant for the present-day needs (mean score 1.41 ± 0.54).

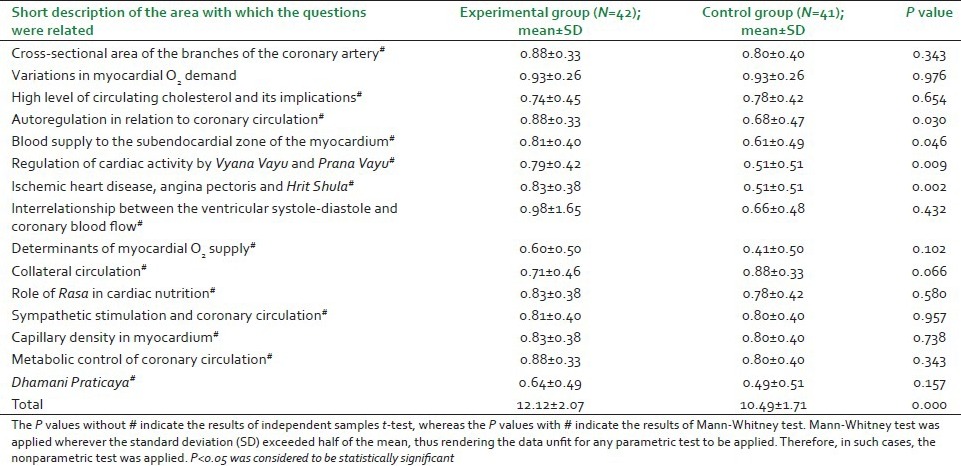

CSL

Table 3 depicts the mean scores obtained by the different groups of students after undergoing the written test. As the table suggests, the difference between the mean scores is statistically significant for four questions (Q4, Q5, Q6, and Q7): The experimental group being able to score better than the control group in each case. For the rest of the questions, however, the difference was not significant. Furthermore, the difference between the total mean scores is statistically highly significant, with the experimental group (mean score 12.12 ± 2.07) scoring better than the control group (mean score 10.49 ± 1.71, P = 0.000).

Table 3.

The groupwise results of the written test for the second experiment CSL

On analyzing the feedback received, we observed that the mean scores were less than 2 for all the statements, which indicates that the students perceived CSL to be more appealing. The students also felt that CSL provided them with better insights into the application aspects (mean score 1.32 ± 0.47).

CSGD

As we did not have a control group to compare the results with, we had to rely upon the feedback that we received. On analyzing the feedback from the learners, it was observed that the mean scores for each statement were less than 3. This shows that a majority of students perceived the CSGD to be better than the conventional method.

DISCUSSION

Though integrative interpretations of the classical Ayurveda textbooks are available in some scholarly books and journal articles, such scholarly literature has not become a part of routine teaching in Ayurveda colleges. This is especially true with the subjects such as Rachana Sharira (Anatomy) and Kriya Sharira (Physiology). The major reason for this is, unfortunately, the syllabus prescribed by the CCIM which lists out the topics belonging to ‘biomedical sciences’ and ‘Ayurveda’ discretely under different papers and sections, thus attempting at no integration. This has prompted many authors to write textbooks that are ‘in accordance with the syllabus prescribed by CCIM’. Students generally prefer consulting the textbooks that are ‘in accordance with the syllabus’ and this trend has posed a threat of students learning Ayurveda only for the namesake. This obviously leads to a state where two mutually unrelated explanations are held simultaneously in an unacknowledged cognitive dissonance.[11] In fact Ayurveda, in its original form has always been open to other streams of sciences. For instance, Sushruta has endorsed this openness as follows: “One cannot become a good physician by studying only one stream of science; rather, one should study various streams of sciences to be a successful physician”.[35]

In spite of the availability of such descriptions in classical textbooks, ‘Educational research’ is still in its infantile state as far as Ayurveda education is concerned. There are no methodically conducted studies to suggest how Ayurveda should be taught in colleges, especially in the context of the recent advances in biomedical sciences. ‘Are the epistemological bases of the two streams complementary to each other?’, ‘should they be allowed to merge?’, and ‘If such a merger is needed, what are the means to achieve this?’ – are a few vital questions that have remained unanswered. Many scholars and sociologists believe that there cannot be an entity like ‘integrative medicine’. They argue that the core features of the two knowledge systems are mutually incompatible.[15] However, this view does not merit much attention as it lacks an in-depth understanding of both the sciences. Further, the recent advances in certain areas of biomedical sciences, such as systems biology, pharmacogenomics, chronobiology, stem cell biology, tissue engineering, neuroimmunoendocrinology, and biology of gut microbiota have strengthened the worldview that Ayurveda puts forth.[36,37,38]

With this background, the present study was planned to incorporate ‘Ayurveda-biomedicine integration’ in the subject Kriya Sharira. ‘Integration’ in fact is being seen as a strategy for making educational experiences coherent, relevant, and engaging; connecting diverse disciplines; and facilitating higher-order learning.[39] In this context, the results of our study assume importance as there is a paucity of systematically conducted studies that evaluate the effectiveness of integrative approaches in Ayurveda education. The Integrative module (IMCP) that we designed and evaluated seems to have served the purpose of showing pointers to the possible ways of teaching the two sciences in an integrative manner. Similar modules have been prepared and evaluated in the context of medical education, the results of which are comparable with those of our study.[40,41] CSL is intended at providing various degrees of early clinical exposure to the students in their preclinical years of study and therefore, aims at vertical integration. This also involves active learning. The results of our study are consistent with other similar studies.[18,42] CSGD basically encourages interaction within the members of the group along with promoting communication skills. This is especially suitable for difficult subject matter involving complex facts. Because group sessions increase active participation, the members also learn from each other.[43] There have been several studies that examine the potential of small group learning in other fields of education.[20,21,22,23,24] Though we could not assess the results of this intervention objectively in our study, the student feedback suggests that this method is effective.

Implications of the study

The current study may be taken as a lead in planning the future course of Ayurveda education. As the next step, similar studies could be planned in other subjects and the merits of integrative approaches may be examined. These approaches may be incorporated into various faculty development programs so as to train the teachers in these methods. As the final outcome, an integrative curriculum may be envisioned once sufficient numbers of such studies are available.

Strengths of the study

The study shows that development of testable integrative methods of teaching is possible in the context of Ayurveda education.

The study shows that bringing the scholarly literature into the graduate level classrooms is possible with the meticulously planned interventions.

The study also shows that integrative approaches make the topics likable and help in avoiding cognitive dissonance.

Limitations of the study

Our study had a few limitations, of which the following are important:

During the first and second experiment, both the experimental group and the control group of students were receiving the instructions simultaneously, though in separate teaching sessions. Hence, we could not avoid any interactions among the students belonging to the different groups outside the classroom.

Further, the instructor for both the groups was the first author of the present study, and hence, we could not avoid the possible ‘carry over effect’, because of which, there might have been some amount of ‘mixing up’ of the contents during the lecturing sessions. Therefore, we suggest placing the two groups temporally distant, in the future studies of this kind.

We could not assess long-term learning outcomes because of time restrictions.

These integrative methods may not be applicable to all the topics that appear in the syllabus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank all the students who participated in these experiments enthusiastically. The authors also acknowledge the support and facilities they received from the Department of Kriya Sharir, Faculty of Ayurveda, Banaras Hindu University, during the present work. We fondly acknowledge the help of all the anonymous reviewers of J-AIM who were instrumental in giving this article the present shape.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Report submitted by Udupa KN. Committee on Ayurveda Research Evaluation. 1958. [Last accessed on 2013 May 14]. Available from: https://nrhm-mis.nic.in/ui/who/PDF/Udupa%20K.N.%20Committee%20on%20Ayurvedic%20Research%20and%20Evaluation%201958.pdf .

- 2.Patwardhan B, Joglekar V, Pathak N. Vaidya-scientists: Catalysing Ayurveda renaissance. Curr Sci. 2011;100:476–83. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch C. An overview of the education and practice of global Ayurveda. In: Wujastyk D, Smith FM, editors. Modern and Global Ayurveda: Pluralism and Paradigms. Albany NY: SUNY Press; 2008. pp. 129–38. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pathak NY. Ayurveda education: A student's perspective. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2010;1:124–7. doi: 10.4103/0974-7788.64410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patwardhan K. Governance of higher education in Indian systems of medicine: Issues, concerns, and challenges. In: Kadam S, editor. Perspectives on Governance of Higher Education (Issues, concerns and challenges) Pune: Bharti Vidyapeeth Deemed University and Centre for Social Research and Development; 2010. pp. 127–39. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narayan J. Teaching reforms required for Ayurveda. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2010;1:150–7. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.65075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patwardhan K. How practical are the “teaching reforms” without “curricular reforms”? J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2010;1:174–6. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.72612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patwardhan K, Gehlot S, Singh G, Rathore HC. The ayurveda education in India: How well are the graduates exposed to basic clinical skills? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep113. 197391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patwardhan K, Gehlot S, Singh G, Rathore HC. Global challenges of graduate level Ayurvedic education: A survey. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2010;1:49–54. doi: 10.4103/0974-7788.59945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patwardhan K, Gehlot S, Singh G, Rathore HC. Graduate level Ayurveda education: Relevance of curriculum and teaching methodology. J Ayurveda. 2009;3:74–82. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wujastyk D. Interpreting the image of the human body in premodern India. Int J Hindu Stud. 2009;13:189–228. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandra S. Status of Indian medicine and folk healing: With a focus on integration of AYUSH medical systems in health care delivery. Ayu. 2012;33:461–5. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.110504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhattacharya J. Epistemological encounter in anatomy and health: Colonial experiences in India. Indian J Hist Sci. 2008;43:163–210. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharya J. The knowledge of anatomy and health in Āyurveda and modern medicine: Colonial confrontation and its outcome. J Med Hum Soc Stud Sci Technol. 2009;1:1–51. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sujatha V. What could ‘integrative medicine’ mean? Social science perspectives on contemporary Ayurveda. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2011;2:115–23. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.85549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klement BJ, Paulsen DF, Wineski LE. Anatomy as the backbone of an integrated first year medical curriculum: Design and implementation. Anat Sci Educ. 2011;4:157–69. doi: 10.1002/ase.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik AS, Malik RH. Twelve tips for developing an integrated curriculum. Med Teach. 2011;33:99–104. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.507711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walters MR. Case-stimulated learning within endocrine physiology lectures: An approach applicable to other disciplines. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(6 Pt 2):S74–8. doi: 10.1152/advances.1999.276.6.S74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams B. Case based learning: A review of the literature: Is there scope for this educational paradigm in prehospital education? Emerg Med J. 2005;22:577–81. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.022707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaques D. Teaching small groups. BMJ. 2003;326:492–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7387.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaudet AD, Ramer LM, Nakonechny J, Cragg JJ, Ramer MS. Small-group learning in an upper-level university biology class enhances academic performance and student attitudes toward group work. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Jong Z, van Nies JA, Peters SW, Vink S, Dekker FW, Scherpbier A. Interactive seminars or small group tutorials in preclinical medical education: Results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:79. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreri SP, O’Connor SK. Redesign of a large lecture course into a small-group learning course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77:13. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholl TA, Lou K. Model for small-group problem-based learning in a large class facilitated by one instructor. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76:117. doi: 10.5688/ajpe766117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guyton AC, Hall JE. 11th ed. Noida, India: Elsevier; 2008. Textbook of Medical Physiology. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrett KE, Barman SM, Boitano S, Brooks HL. 23rd ed. New Delhi, India: Tata McGraw-Hill; 2010. Ganong's Review of Medical Physiology. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyle B, Bragg J. Making primary connections: The cross-curriculum story. Curriculum J. 2008;19:5–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patwardhan K. Varanasi, India: Chaukhambha Orientalia; 2008. Human Physiology in Ayurveda. Jaikrishnadas Series No. 134; pp. 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dwarikanath C. 3rd ed. Varanasi, India: Chaukhamba Orientalia; 1996. Introduction to Kayachikitisa. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desai RR. 5th ed. Allahabad, India: Baidyanath Ayurveda Bhawan; 2008. Ayurvediya Kriya Sharir. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patwardhan K. The history of the discovery of blood circulation: Unrecognized contributions of Ayurveda masters. Adv Physiol Educ. 2012;36:77–82. doi: 10.1152/advan.00123.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pandey VN, Pandey A. A comparative study on concepts of circulation of blood: A view point of Ayurveda. Anc Sci Life. 1990;9:178–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bland JM, Altman DG. Cronbach's alpha. BMJ. 1997;314:572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Streiner D, Norman G. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1995. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Use. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Acharya JT, editor. Chapter 4, Verse 7. Varanasi, India: Chaukhambha Surbharati Prakashan; 1994. Sushruta Samhita of Sushruta. Sutra Sthana. Prabhashaniya; p. 17. The Chaukhmbha Ayurvijnan Granthamala no 42 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patwardhan K. Is biomedicine on its way to becoming Ayurveda? Ayurveda Education (Blog) [Last accessed on 2013 May 14]. Available from: http://kishorpatwardhan.blogspot.in/2011/02/is-biomedicine-on-its-way-of-becoming.html .

- 37.Patwardhan B. J-AIM-A renaissance for Ayurveda. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2010;1:1–2. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.59816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hankey A. The ontological status of western science and medicine. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2012;3:119–23. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.100170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearson ML, Hubball HT. Curricular Integration in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76:204. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7610204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghosh S, Pandya HV. Implementation of integrated learning program in neurosciences during first year of traditional medical course: Perception of students and faculty. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8:44. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-8-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vyas R, Jacob M, Faith M, Isaac S, Rabi S, Satishkumar S, et al. An effective integrated learning program in the first year of the medical course. Natl Med J India. 2008;21:21–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sathishkumar S, Thomas N, Tharion E, Neelakantan N, Vyas R. Attitude of medical students towards Early Clinical Exposure in learning endocrine physiology. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walton H. Small group methods in medical teaching. Med Educ. 1997;31:459–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1997.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]