Abstract

Background:

Lomotil (diphenoxylate atropine combination) has been in use as an antidiarrhoeal agent. Due to presence of opioid (diphenoxylate), there are chances of abuse. The reports of abuse of lomotil have been few in published literature. This chart review aimed to evaluate the characteristics of patients with dependence on lomotil coming to our centre.

Materials and Methods:

This retrospective chart review was conducted at the Drug De-addiction and Treatment Centre of PGIMER, Chandigarh, India. The records of patients who had presented to the centre with dependence on Lomotil in the last five years were identified, and clinical details were extracted from the records.

Results:

We identified 41 patients who had presented to our centre with dependence upon lomotil as the primary substance of abuse. The cases were typically married and employed males, educated up to 10th grade, belonging to a rural Sikh extended or joint family. Most of the patients had taken other opioids too. The number of tablets taken in a day varied from 3- to 250 (median 25). The reasons of initiation were to relieve withdrawals, as a cheap substitute opioid, curiosity, and on suggestion of friends.

Conclusion:

Lomotil is a medication with a potential of abuse and regulatory controls are required to prevent escalation of misuse of this easily available prescription drug. Lomotil (diphenoxylate and atropine combination) has been used since a long time as an anti-diarrheal agent. Reports of abuse of diphenoxylate had surfaced. We present a series of 41 cases of opioid dependence presenting with the use of the diphenoxylate as the primary substance. The cases were typically married and employed males, educated up to 10th grade, belonging to a rural Sikh extended or joint family. Most of the patients had taken other opioids too. The number of tablets taken in a day varied from 3 to 250 (median 25). The reasons of initiation of diphenoxylate were to relieve withdrawals, as a cheap substitute opioid, curiosity, and suggestion of friends. Regulatory controls are needed to prevent escalation of use of this easily available prescription opioid.

Keywords: Dependence, diphenoxylate, India, lomotil, opioids

INTRODUCTION

Lomotil (2.5 mg diphenoxylate and 0.025 mg atropine combination) has been used as an antidiarrheal since a long time and had been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1960s. Diphenoxylate, a weak opioid agonist has been considered as a drug of low abuse potential. Diphenoxylate has been hence kept in schedule H of Drugs and Cosmetics Rules in India and schedule V of controlled substances of the FDA.[1,2] There have been however, only case reports of diphenoxylate being abused by patients with medical illnesses and substance users.[3,4] It has also been tried during detoxification from opioids and has been shown to decrease withdrawals.[5,6]

Diphenoxylate hydrochloride is devoid of morphine-like subjective effects at therapeutic doses. At high doses, it exhibits codeine-like subjective effects. To limit the extent to which the drug can be abused, a small amount of atropine is added, which can also augment the anti-diarrheal effect of diphenoxylate, however, at high doses causes unpleasant side effects like tachycardia, dry mouth and blurring of vision. However, a considerably high dose of atropine is required to produce these intolerable side-effects.[7] Thus abuse of diphenoxylate for opiate like effects becomes a valid possibility. In our experience, many opioid dependent patients attending our treatment center have reported the use of diphenoxylate at some point of time. Diphenoxylate dependence has been an understudied subject. We thus, report a series of cases who had sought treatment in the last 5 years at our center, with diphenoxylate as the primary substance of abuse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was a retrospective chart based study conducted at the Drug Deaddiction and Treatment Center (DDTC) of Post-Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh. The DDTC gets referred and non-referred patients from North-India. The center provides both in-patient and out-patient services to the treatment seekers through pharmacological and psychotherapeutic means. The treatment seekers comprises primarily of alcohol and opioid dependent patients, though other substance users are also frequently encountered. The opiates commonly being abused by the treatment seekers include the raw preparations from the opium poppy (exudates and poppy husk), dextropropoxyphene, codeine containing cough syrup, and injectable buprenorphine and pentazocine.

Diphenoxylate using treatment seekers at DDTC were identified from the consecutive case records of the last 5 years by trained personnel. Those cases of opioid dependence who had presented with the predominant use of the diphenoxylate were identified from the records. Subsequently, detailed information was extracted from the records using a structured proforma. The demographic details gathered included age, gender, education, occupation status, religion, residence, and type of family. Clinical information about the substances used, reason of initiation of diphenoxylate, duration of opioid use in general, and diphenoxylate in particular, usual and maximum number of tablets consumed, any comorbid medical illnesses, and the outcome were recorded. The outcome was coded as improved if the patient was abstinent at the last follow-up, unchanged if the patient continued to take diphenoxylate, and relapsed if the patient resumed taking the substance after a period of abstinence.

RESULTS

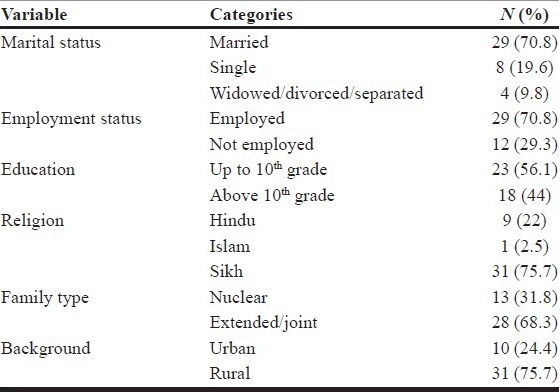

Form the records, 41 cases were identified as currently taking diphenoxylate. All of the cases were males. The other demographic characteristics of the sample are depicted in Table 1. The patients were typically married, employed, educated till 10th grade, belonged to Sikh religion of extended or joint family of the rural background. The mean age of the sample was 32.4 years (standard deviation 9.5 years, range 18-56 years, and median 31 years).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample

The average number of diphenoxylate tablets being consumed in a day varied from 3 to 250 (median 25 tablets/day, interquartile range (IQR) 5-60, mean 47.4). The maximum number of diphenoxylate tablets being consumed in a day varied from 6 to 400 (median 100 tablets/day, IQR 50-150, mean 118). The median duration of use of opioids was 72 months (IQR 48-120 months, mean 103 months), and the median duration of use of diphenoxylate was 48 months (IQR 24-60 months, mean 57 months).

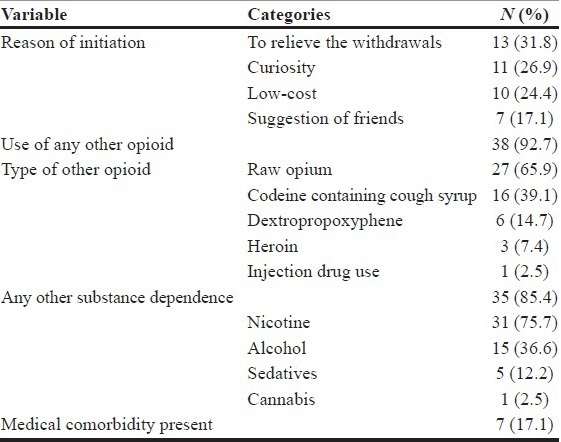

The clinical characteristics of the patients are depicted in Table 2. Majority of the patients had tried other opioids and were concomitantly dependent on the other substances. Medical comorbidity was present in 7 patients and included asthma, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, nephrolithiasis, limb paresis, seizures, and wrist fracture in one patient each. Follow-up data was available for 33 patients (80.5% of the sample), with a median duration of follow-up 3 months (IQR 1-12 months, mean 9.9 months). The follow-up was recorded as improved in 25 cases, and relapsed or unchanged in 8 cases.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the sample

DISCUSSION

This retrospective case series draws attention to the problem of misuse of diphenoxylate by opioid dependent patients. This is the largest series that documents the abuse of diphenoxylate in the clinical population. Concomitant use of other opiates was common, and was present in a majority of the sample suggesting that diphenoxylate was being used as just another opiate in their drug taking career. It has been seen that opioid addicts many a times change from the use of one opiate drug to another, depending upon environmental necessity and novelty seeking.[8,9] The most common reason of initiation of diphenoxylate in the present sample was to reduce withdrawals when other opiates were not available.

Past evidence suggests that with time, the commonly used opioids change in a geographical region.[8,10] Prescription opioid use has seen a rise with tighter international control of narcotics. The ease of availability of diphenoxylate from the chemist shops and low-cost is likely to contribute to preference toward this medication among the opioid users. Timely steps to effectively regulate its sale can avert misuse of this drug.

Due to the retrospective nature of this study, certain clinical information could not be obtained, for example, features of atropinism encountered, additive effects with other substances etc. Nonetheless, this work draws concern towards the need for a heightened level of the caution among physicians while prescribing this medication and stricter legal measures to prevent the diversion.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Notoifi.pdf. [Last accessed on 2012 Sep 5]. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/html/Notoifi.pdf .

- 2.c_cs_alpha.pdf. [Last accessed on 2012 Sep 5]. Available from: http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/schedules/orangebook/c_cs_alpha.pdf .

- 3.Firoozabadi A, Mowla A, Farashbandi H, Gorman JM. Diphenoxylate hydrochloride dependency. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13:278–80. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000281491.65311.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao R, Agrawal A, Pal HR, Mohan I. Lomotil dependence: A note of caution. Natl Med J India. 2005;18:330–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleinman MH, Arnon D. The use of diphenoxylate hydrochloride (Lomotil) in the management of the minor withdrawal syndrome during methadone detoxification: A clinical report. Br J Addict Alcohol Other Drugs. 1977;72:167–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1977.tb00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ives TJ, Stults CC. Short-course diphenoxylate hydrochloride for treatment of methadone withdrawal symptoms. Br J Psychiatry. 1983;143:513–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.143.5.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutstein HB, Akil H. Opioid analgesics. In: Hardman, Limbird LE, editors. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 569–619. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamunen K, Paakkari P, Kalso E. Trends in opioid consumption in the Nordic countries 2002-2006. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:954–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green TC, Black R, Grimes Serrano JM, Budman SH, Butler SF. Typologies of prescription opioid use in a large sample of adults assessed for substance abuse treatment. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sproule B, Brands B, Li S, Catz-Biro L. Changing patterns in opioid addiction: Characterizing users of oxycodone and other opioids. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:68–9. 69.e1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]