Abstract

Primary oral mucosal melanoma is a rare aggressive neoplasm and accounts for only 0.2-8% of all reported melanomas. It is a malignant neoplasm of melanocytes that may arise from a benign melanocytic lesion or de novo from melanocytes within normal skin or mucosa. It is considered to be the most deadly and biologically unpredictable of all human neoplasms, having the worst prognosis. In this article, we report a case of oral melanoma in a 52-year-old female patient with a chief complaint of black discolouration of the maxillary gingiva and palate.

Keywords: Gingiva, malignant neoplasm, oral mucosal melanoma, palate

INTRODUCTION

Melanoma is a malignant neoplasm of melanocytic origin that arises from a benign melanocytic lesion or de novo from melanocytes within otherwise normal skin or mucosa. These melanocytes are derived from neural crest cells and produce the melanin pigment of the basal layer of epithelium.1,2,3

Oral malignant melanoma (OMM) affects all races; higher incidence has been reported in Japan, India and Africa than western countries. Globally about 160,000 new cases of melanoma are diagnosed yearly. According to a WHO report, about 48,000 melanoma-related deaths occur worldwide every year.4 Oral melanoma represents 50% of all mucosal melanomas, and more than 20% of all melanomas of the head and neck region, 1.6% of all head and neck malignancies, 1.3% of all cancers, and 0.5% of all oral malignancies in the world literature.3

CASE REPORT

A 52-year-old female reported to the Out Patient Department, Drs. Sudha and Nageswarao Siddhartha Institute of Dental Sciences, Gannavaram, India, with a complaint of black discolouration in the upper gums in relation to the front teeth since 6 months. The patient gave a history of extraction of lower posterior teeth 5 yrs previously and past medical history was non-contributory.

On intraoral examination, a diffuse, sessile and asymptomatic swelling, with a smooth surface and of black colour was observed on the maxillary gingiva of anterior teeth involving both the labial as well as palatal side. On the right side of the maxilla the lesion was elevated and a well-defined blackish-brown colour discolouration present on right buccal and lingual mucosa [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Intraoral photograph showing palatal extension of the lesion

Figure 2.

Intraoral photograph showing the lesion involving the gingiva

On palpation the left submandibular lymph node was palpable and approximately 2 × 2 cm, non-tender, firm, which was fixed to the underlying tissues. Based on clinical appearance pigmented lesions like melanoacanthoma, nevus and melanoma were considered under differential diagnosis made. Blood investigations and radiographic features did not reveal any significant findings. Incisional biopsy of the lesion was performed and sent for histopathological examination.

Haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections showed invasion of the connective tissue stroma by sheets and islands of pleomorphic epithelioid, spindle cell atypical melanocytes containing brownish to black pigment in the cytoplasm. The lesion was diagnosed as melanoma [Figures 3 and 4]. Further this was confirmed immunohistochemically by using HMB-45, which showed strong positivity of the tumour cells [Figure 5].

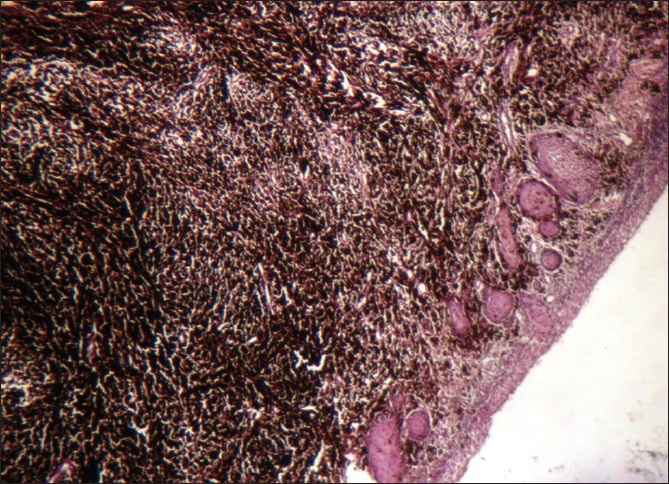

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph of the lesion showing malignant melanocytes with extensive melanin pigementation infiltrating the connective tissue (H and E, ×10)

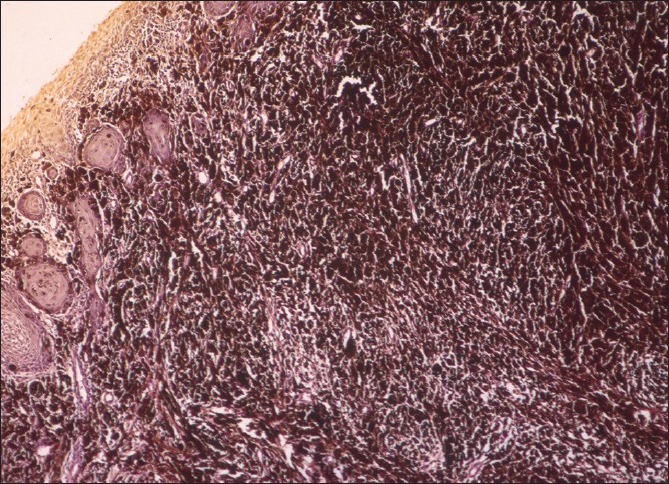

Figure 4.

High power photomicrographic view of the filed shown in Figure 3. Streaming pattern of pleomorphic tumour cells are more obvious (H and E, ×20)

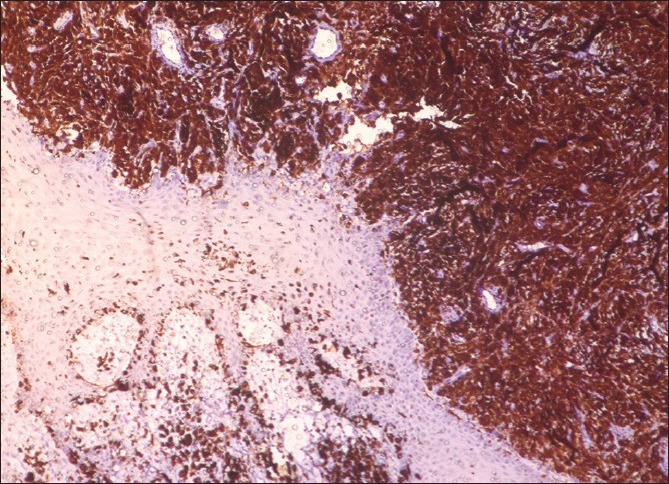

Figure 5.

Sections stained with HMB-45. Strong positivity of tumour cells infiltrating into the connective tissue is discernible (HMB-45, ×10)

DISCUSSION

Oral malignant melanoma is an extremely rare neoplasm of melanocytes which was reported by Weber in 1856.5 It is biologically an aggressive neoplasm with a poorer prognosis than its cutaneous counterpart.

The aetiology of malignant melanoma remains elusive. The risk factors for the development of melanoma include UV radiation, skin and hair colour, numerous freckles, tendency to burn and tan poorly, PUVA therapy, tanning salons, presence of nevi (numerous, large, atypical), xeroderma pigmentosum, immunosupression, denture irritation, exposure to tobacco, chemicals, petroleum and printing products. Primary oral melanomas originated either from a nevus or pre-existing pigmented lesion currently most thought to arise de novo.6,7,8 In our case, patient was not exposed to above factors the possible aetiology may be de novo.

The genetic factors include mutations of the gene CDKN2A (Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2A), encoding the tumour suppressor protein p16 located on chromosome 9p21 which confers susceptibility to familial malignant melanoma. Other genes include RB1, CDK4gene on chromosome 12q15, RB1 and PTEN/MMAC1.1,7,9

Melanomas occur in all ages between 7 and 90 years and are most prevalent in the 5th decade. Males are more commonly affected than females. The most common sites in the head and neck region includes conjunctiva, sinonasal cavity, oral cavity, pharynx, larynx and upper oesophagus (in decreasing order). In the oral cavity 80% cases involves the gingiva and palate.6 Occurrence in the mandible, buccal mucosa, lips tongue and floor of mouth is not uncommon.4,8,10,11,12 In our case it involved the entire maxillary gingiva and palate.

Melanomas are asymptomatic in their clinical appearance and silently progresses and therefore go unnoticed by the patient contributing delay in diagnosis. Early lesions exhibits pigmented patches with alteration in colour and texture of the skin or mucosa. Later lesions shows thick elevated brownish black surfaces with are without ulceration. They are classified (Tanaka et al.) into five types pigmented nodular, non-pigmented nodular, pigmented macular, pigmented mixed, and finally non-pigmented mixed. Some of the tumours are amelanotic. Amelanotic melanoma is a rare tumour which is difficult to diagnose and comprises 10% of all melanomas.2,4,7,10,11,13 In our case it was pigmented mixed because of variegated colour of the lesion in different regions of the mouth.

Oral melanoma may not have the typical ABCDE characteristics of skin melanoma but it offers some help in the diagnosis. In our patient all of the ABCDE criteria were present.6 Radiographically, primary melanomas rarely involves the jaw bones. If it is involved it should be distinguished from the osteomyelitis.4

The differential diagnosis of OMM include of oral melanotic macule, melanoplakia, pituitary-based Cushings syndrome, post-inflammatory pigmentation, melanoacanthoma, amalgam tattoo, Addisons disease, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and melanocytic nevi.2,4,13 But our patient did not have any other signs or symptoms suggesting any of these lesions.

Microscopically mucosal melanomas can show two principal patterns: An in situ pattern in which the neoplasm is limited to the epithelium and the epithelial-connective tissue interface (junctional), and an invasive pattern in which the neoplasm is found within the supporting connective tissue. A combined pattern of invasive melanoma with in situ component is typical for most advanced lesions.2,14,15

Melanoma in situ shows an increase in atypical melanocytes. Although these atypical melanocytes have angular and hyperchromatic nuclei, mitoss tend to be sparse. The melanocytes may form aggregates or may be irregularly distributed in a junctional location.

The melanocytes present in invasive melanomas show a variety of cell types including epithelioid, spindle and plasmacytoid. They typically have large, vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli; mitoses may be present but usually not in large numbers. They are usually aggregated into sheets or alveolar groups and less commonly neurotropic or desmoplastic configurations. In our case the histopathological features coincide with the invasive pattern.

Melanoma shows wide spectrum of histopathological features which are confused with mesenchymal, epithelial and neural tumours, S-100 and HMB-45 are more frequently expressed than Melan-A and these markers are helpful to confirm the diagnosis.15 Our case showed positive for HMB-45.

Greene et al.16 proposed the criteria for primary malignant melanoma which includes: (1) Demonstration of melanoma in oral mucosa (2) Presence of junctional activity (3) Inability to demonstrate extra oral primary melanoma. Our present case fulfills the above criteria.

The Clarks grading system assessing the depth of invasion and Breslow measuring the thickness of tumour from the surface of the epidermis to the greatest depth of the tumour have no validation as prognostic factors in OMM due to rarity of the lesion and absence of a true dermis in the oral cavity. However, a simple TNM staging with prognostic value have three stages.4,8,11,13,15,17 The present case fits into Level 2 Stage 1.

The common sites of metastases are lymph nodes, liver and lungs, with wide dissemination in the advanced disease. The treatment policy for OMM is unclear but an excisional biopsy of the lesion followed by a wide surgical excision where the diagnosis is proven is current choice for most of the surgeons with radiotherapy and chemotherapy as adjunctive treatment methods.6

It is well known that early diagnosis and treatment of melanoma can reduce mortality. If diagnosed early when the malignant cells are limited to the epithelium or invasion is minimal. Melanoma is either 100% curable by excision (for in situ lesion) or is associated with a 5-year survival rate of 95% (for lesions <1 mm in thickness and without ulceration). In contrast, the 5-year survival rate for cutaneous melanomas >4-mm thickness with ulceration is only 45%.14,18

Poor prognosis of melanoma may be due to early invasion of deeper structures due to proximity of bone and muscles increasing likelihood of metastasis. Rich vascular supply of oral cavity further aids in dissemination of melanoma.19

A variety of serological markers like serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), melanoma-inhibiting activity (MIA), S100B and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are available for melanoma. Elevated levels of LDH and MIA are associated with more advance stages and poorer prognosis. These markers are useful in monitoring the patients clinical course of the disease and response to therapy.5

The reported average duration of life from the point of diagnosis was about 18 months and 79% of patients died within 5 years. Few authors reported that that the 5-year survival rate of intraoral melanoma does not exceed 5-9%. In general, the survival rates are poor and are worst for those cases with metastasis.13,20

CONCLUSIONS

Intraoral primary melanomas are rare and differ from their cutaneous part in behaviour and prognosis. This lesion should be diagnosed early from other pigmented lesions, especially if they occur in high-risk sites like gingiva or palate, so that successful treatment with better prognosis is possible.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reddy BV, Sridhar GR, Anuradha CH, Chandrasekhar P, Lingamaneni KP. Malignant melanoma of the mandibular gingiva: A rare occurrence. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21:302–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.66644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Femiano F, Lanza A, Buonaiuto C, Gombos F, Di Spirito F, Cirillo N. Oral malignant melanoma: A review of the literature. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:383–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmadi-Motamayel F, Falsafi P, Baghaei F. Report of a rare and aggressive case of oral malignant melanoma. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;17:47–51. doi: 10.1007/s10006-012-0311-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hicks MJ, Flaitz CM. Oral mucosal melanoma: Epidemiology and pathobiology. Oral Oncol. 2000;36:152–69. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(99)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vikey AK, Vikey D. Primary malignant melanoma, of head and neck: A comprehensive review of literature. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gondivkar SM, Indurkar A, Degwekar S, Bhowate R. Primary oral malignant melanoma: A case report and review of the literature. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:41–6. doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a14113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajendran R, Sivapathasundharam B. Shafer, Hine, Levy's Shafer's Text Book of Oral Pathology. 6th ed. Vol. 80. India: Elsevier; 2009. Benign and malignant tumors of the oral cavity; p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manganaro A, Hammond H, Dalton M, Williams TP. Oral melanoma: Case report and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;85:670–6. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh M, Lin J, Hocker TL, Tsao H. Genetics of melanoma tumerogenesis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:15–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rapidis AD, Apostolidis C, Vilos G, Valsamis S. Primary malignant melanomaof oral mucosa. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1132–9. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss JE, Strauss SI. Oral malignant melanoma: A case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:972–6. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takagi M, Ishikaw G, Wataru M. Primary malignant melanoma of oralcavity in Japan, with special reference to mucosal melanosis. Cancer. 1974;34:358–70. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197408)34:2<358::aid-cncr2820340221>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashemipour MS. Malignant melanoma of the oral cavity. J Dent. 2007;4:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah H, Vyas Z. Malignant melanoma: A case report. J Adv Dent Res. 2010;1:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devi P, Bhovi T, Jayaram RR, Walia C, Singh S. Malignant melanoma of the oral cavity showing satellitism. J Oral Sci. 2011;53:239–44. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.53.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perrotti V, Piattelli A, Rubini C, Fioroni M, Petrone G. Malignant melanoma of gingiva: A case report. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1724–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.12.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peckitt NS, Wood GA. Malignant melanoma of oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70:161–4. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Auluck A, Zhang L, Desai R, Rosin MP. Primary malignant melanoma of maxillary gingiva – A case report and review of the literature. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74:367–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wanjari PV, Warhekar AM, Wanjari SP, Reddy V, Tekade S, Shrivastava P. Primary Oral Malignant Melanoma. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2011;23:76–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Symvoulakis EK, Kyrmizakis DE, Drivas EI, Koutsopoulos AV, Malandrakis SG, Skoulakis CE, et al. Oral mucosal melanoma: A malignant trap. Head Face Med. 2006;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]