Abstract

BACKGROUND

Alcohol has been shown to have a number of harmful effects on the lung, including increasing the risk of pneumonia and bronchitis. How alcohol increases the risk of these diseases is poorly defined. RhoA is a small guanosine triphosphate (GTP)ase that plays an integral role in many basic functions of airway epithelial cells. It is not known how alcohol affects RhoA activity in the airway epithelium. We hypothesized that brief alcohol exposure modulates RhoA activity in the airway epithelium through a nitric oxide (NO)/Cyclic GMP (cGMP)/Protein Kinase G (PKG) dependent pathway.

METHODS

Primary airway epithelial cells were cultured and exposed to ethanol at various concentrations and times. The cell layers were harvested and RhoA activity was measured.

RESULTS

Alcohol induced a time- and concentration-dependent decrease in RhoA activity in airway epithelial cells. We were able to block this decrease in activity using Nω-Nitro-l-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME), a nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor. Likewise, we were able to demonstrate the same decrease in RhoA activation using 0.1µM sodium nitroprusside (SNP), an NO donor. To determine the role of cGMP/PKG, we pretreated the cells with a cGMP antagonist analogue, Rp-8Br-cGMPS. This blocked the decrease in RhoA activity caused by alcohol, suggesting that alcohol exerts its effect on RhoA activity through cGMP/PKG.

CONCLUSIONS

Alcohol decreases airway epithelial RhoA activity through an NO/cGMP/PKG- dependent pathway. RhoA activity controls many aspects of basic cellular function, including cell morphology, tight junction formation, and cell cycle progression and gene regulation. Dysregulation of RhoA activity can potentially have several consequences, including dysregulation of inflammation. This may partially explain how alcohol increases the risk of pneumonia and bronchitis.

Keywords: ethanol, nitric oxide, PKG, cGMP, airway epithelium

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol is known to have many harmful effects on the lung, including increased risk of adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS; Moss et al., 1996; Moss and Burnham, 2003), pneumonia (Chalmers et al., 2009; Saitz et al., 1997; de Roux et al., 2006; Fernandez-Sola et al., 1995) and bronchitis (Suadicani et al., 2001; Sisson, 2007). Little is known about how alcohol changes the signaling in the airway epithelium to increase the risk of infection and inflammation.

RhoA is a small GTPase that plays an integral role in many basic functions of airway epithelial cells. RhoA has been shown to be critical in wound closure (Desai et al., 2004), ciliogenesis (Pan et al., 2007), tight junction regulation (Jou et al., 1998), actin cytoskeleton organization (Clements et al., 2005), smooth muscle contraction (Liu et al., 2006), and apoptosis (Moore et al., 2004). All of these functions are important to maintain healthy airway epithelial cells. When these functions are impaired, the airway epithelium is more susceptible to injury and infection, leading to increased pneumonia or bronchitis.

Alcohol has been shown to diminish RhoA activity in the brain in rodent models of alcohol exposure. For instance, chronic alcohol exposure has been shown to cause decreased RhoA activity in rat astrocytes (Martinez et al., 2007). In contrast, increased cerebellar RhoA activity has also been reported in a rat model of fetal alcohol syndrome (Joshi et al., 2006). Very little is known about how alcohol affects RhoA activity in the lung, or what mechanism contributes to the changes.

RhoA mRNA and protein expression have been shown to be modulated through the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells (Sauzeau et al., 2003). In addition, PKG has been shown to be essential in the RhoA-mediated contraction of vascular smooth muscle (Sauzeau et al., 2000). We have previously shown that the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway plays an important role in the innate immunity of the lung, including mucociliary clearance (Wyatt et al., 1998; Sisson et al., 2009) and toll-like receptor 2 expression (Bailey et al., 2010). We have also shown that nitric oxide is produced by the airway epithelium in response to alcohol treatment (Wyatt et al., 2003). We hypothesized that alcohol also modulates RhoA activity through the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway in the airway epithelium.

METHODS

Primary cell isolation and culture

Primary normal human bronchial epithelial cells (NHBE) were isolated from de-identified human lungs that were rejected for transplantation. The lungs were obtained from the International Institute for the Advancement of Medicine (IIAM). The protocol is approved by the IIAM ethics committee and the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Lungs were accepted from males and females age 19–60 with no history of alcohol use, smoking, lung disease, sepsis or active pulmonary infection. This clinical information was obtained by the organ retrieval staff from the medical record and/or the next of kin. The five donors for this series of experiments were ages 26–60. Two died of acute myocardial infarctions and three died of intracranial hemorrhage/stroke. The lungs were not accepted for transplantation for various reasons including: advanced age, hypotension, pulmonary edema and history of asthma as a child with no current symptoms or treatment.

We used the method of Randell et al. (Fulcher et al., 2005) to isolate airway epithelial cells. Briefly, the tracheobronchial tree was dissected from the lung parenchyma, cut into 1–2 cm pieces and placed in Protease XIV (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri) for 24–36 hours. The protease solution was removed and the internal lumen of the airway was scraped. The resulting cells were washed and plated in serum-free media, bronchial epithelial growth media (BEGM; Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) on plates coated with Type I (Sigma) and Type III collagen (Sigma).

Once plated, the cells were fed every 48 hours with BEGM supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin. The cells were cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C and sub-cultured when they reached approximately 80% confluence.

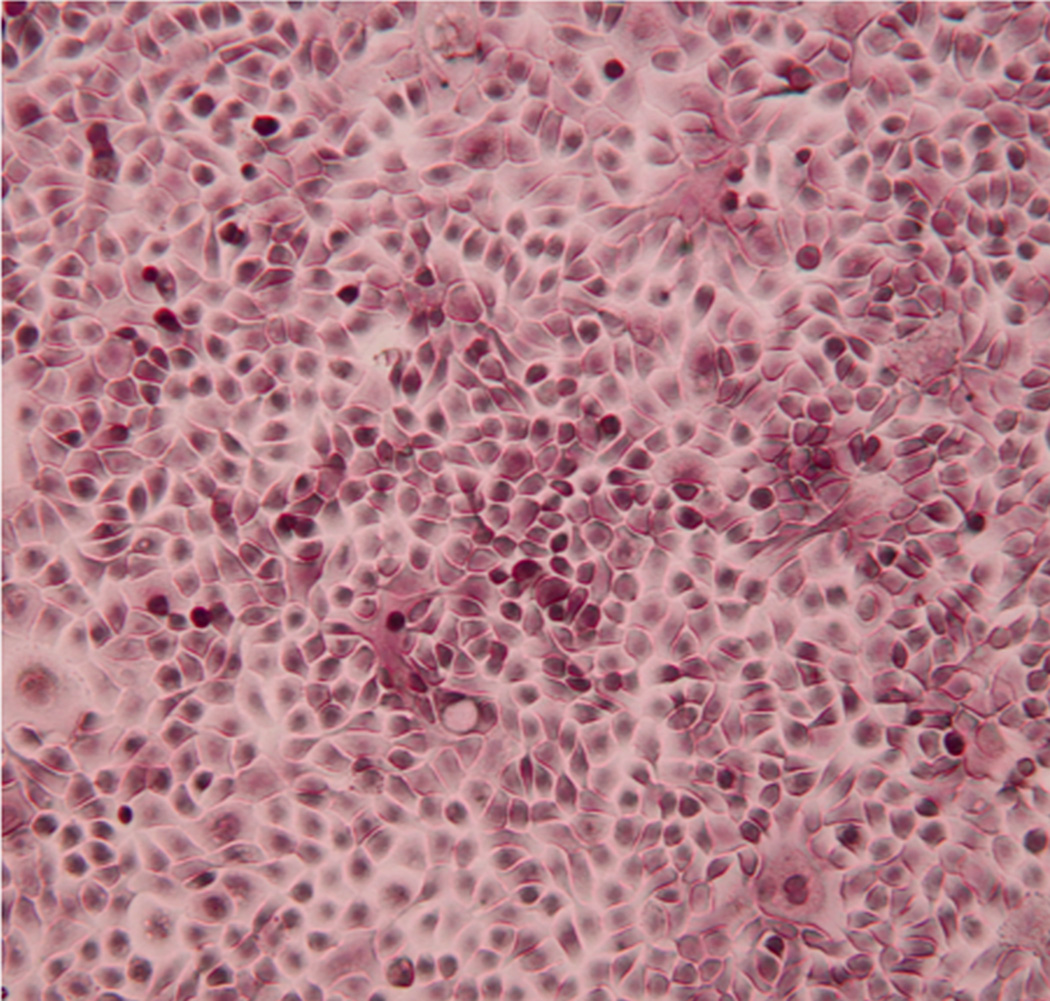

This protocol yielded 200–350 million airway epithelial cells per donor. The cells demonstrate classic cobblestone morphology of primary bronchial epithelial cells (Figure 1). Cells were used in experiments from passage 1–4. The cell phenotype was carefully observed, and if there were >10% of the cells exhibiting a squamous morphology, they were not used for experiments. Each experiment included cells derived from 5 donors.

Figure 1. Typical morphology of airway epithelial cells.

(Phase microscopy 40× magnification.) The cells demonstrate the classic cobblestone morphology of primary airway epithelial cells.

Cell exposure to alcohol

The cells were plated at a concentration of 250,000 cells/ml of media and grown to 50–60% confluence in 60mm culture plates. They were exposed to 25–100mM ethanol (Pharmco-AAPER; Shelbyville, Kentucky) in BEGM for the times indicated in the experiment. Alcohol treatment did not cause any phenotypic changes in the cells at any concentration or time point. Cell viability was the same in treated and untreated cells. The LDH in the untreated cells was 0.161± 0.002 while cells treated with 100mM alcohol for 6 hours was 0.153 ± 0.004. Cells that were intentionally lysed as a positive control had an LDH of 0.537 ± 0.001. In previous experiments using these culture conditions, we have shown no significant alcohol evaporation.(Wyatt and Sisson, 2001)

RhoA activity assay

The level of active (GTP-loaded) RhoA was measured using a RhoA G-LISA kit (Cytoskeleton; Denver, Colorado) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Briefly, the cell monolayers were lysed, clarified, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until the assay could be completed. The protein levels in the samples were determined and then equalized to 3mg/ml with lysis buffer. The samples were mixed with binding buffer and applied to the G-LISA plate. The plate was incubated at 4°C to bind the GTP-loaded RhoA to the plate. The plate was washed, the primary antibody applied, washed, and the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody was applied. The plate was developed, and absorbance was read at 490nm.

Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was determined using a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay (Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. It was performed on supernatants of cells exposed to all concentrations of alcohol.

Statistics

In these experiments, a portion of each subjects’ cells were ‘treated’ and ‘untreated’ so that each subject functioned as its own control. Experiments were also replicated within subjects using different passages of the cells on different days.

The raw optical density data was expressed as % change compared to control cells. All data are reported as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). GraphPad Prism Version 5.0b was used for statistical analysis. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used. Differences were considered significant at p≤0.05.

Reagents

N(G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) and Sodium Nitroprusside were purchased from Sigma. Rp-8-Br-cGMPS was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). All other reagents not specifically stated were purchased from Sigma.

RESULTS

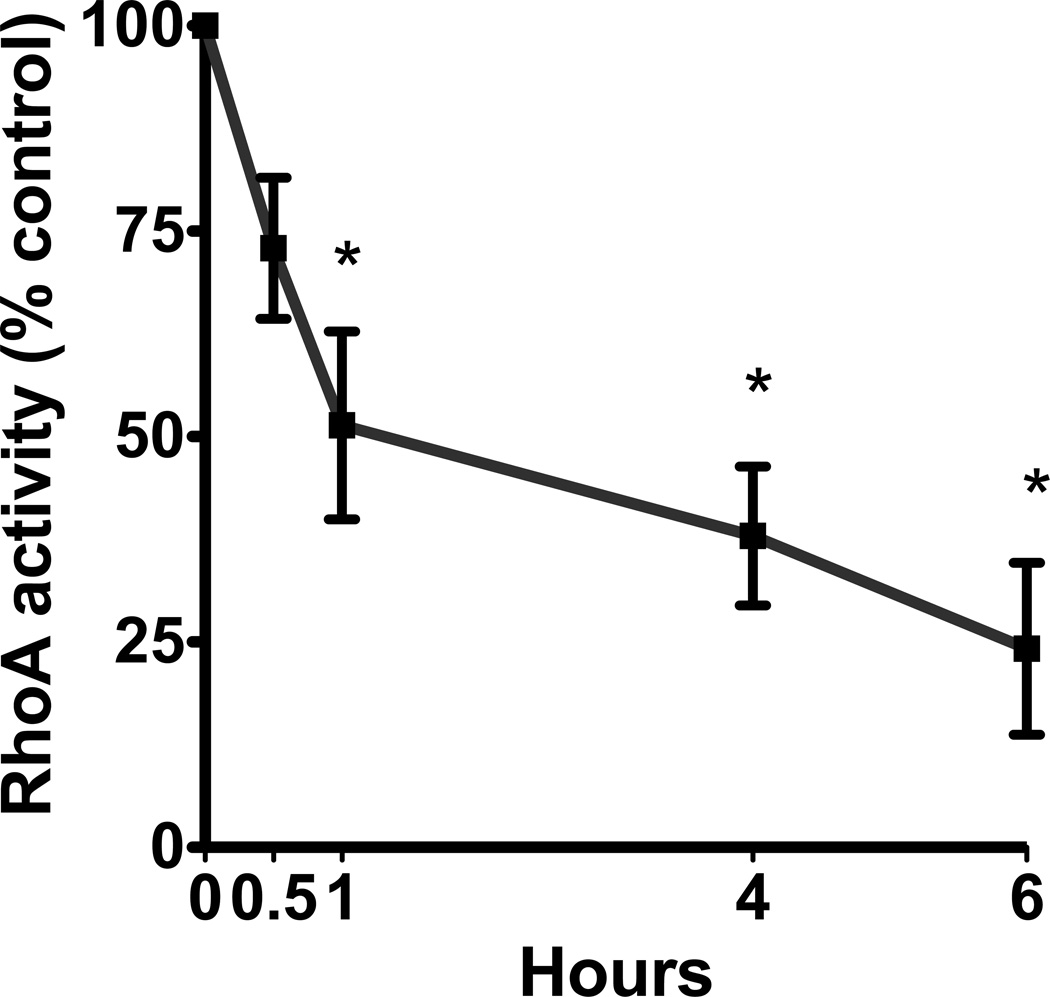

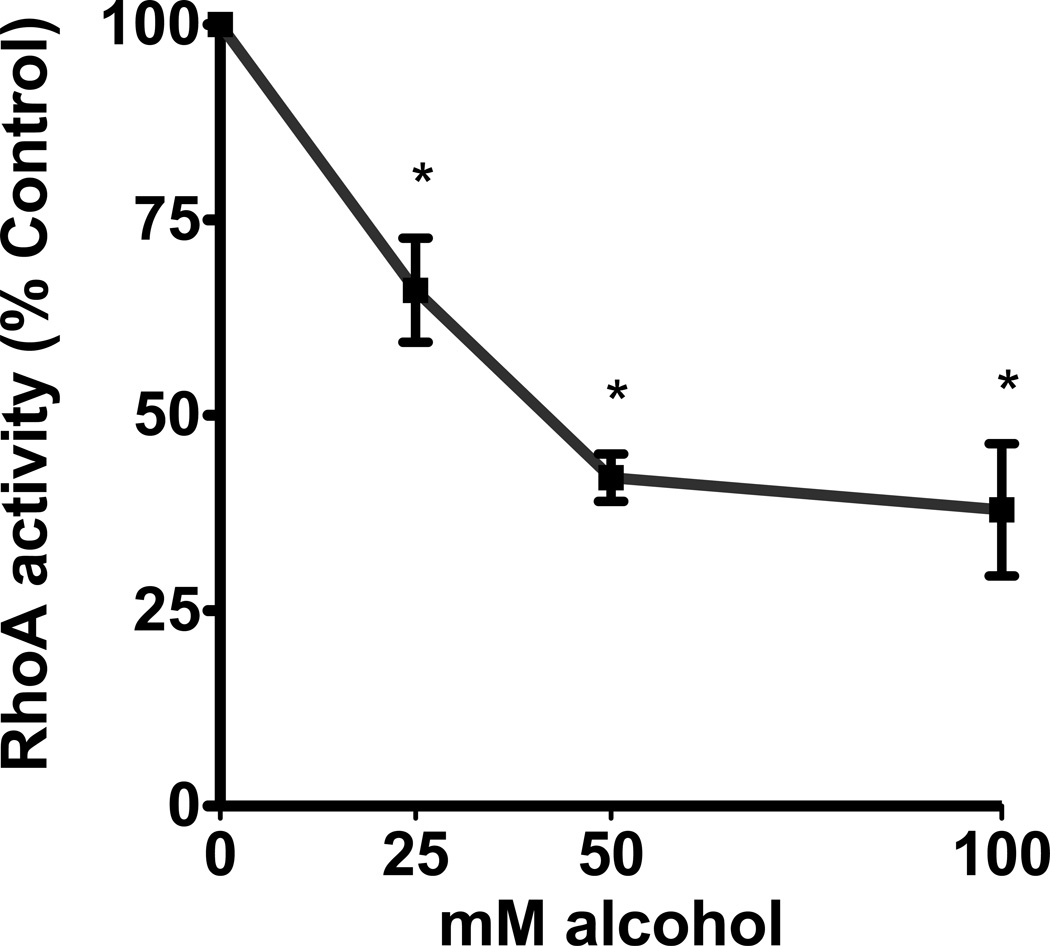

Alcohol decreased RhoA activity in a time- and concentration-dependent manner in the airway epithelium. Cells exposed to 100mM alcohol showed a statistically significant decrease in RhoA activity after 1, 4 and 6 hours of exposure (p<0.0001; n=5). The largest decrease was seen at 6 hours at 24% of control cells (Figure 2a). Likewise, cells that were exposed to varying concentrations of alcohol also showed a concentration-dependent decrease in RhoA activity. After 4 hours of exposure, we observed a statistically significant decrease in RhoA activity with exposure to 25, 50 and 100mM alcohol (p<0.0001; n=5; Figure 2b). The largest decrease was seen at the 100mM concentration, at 38% of the control cells. We hypothesized that the decrease in RhoA activity may be related to alcohol inducing production of nitric oxide (NO) by the airway epithelial cells (Sisson, 1995).

Figure 2. Alcohol induces a time- and concentration-dependent decrease in RhoA activity.

A. NHBE were exposed to 100mM alcohol for 0–6 hours. They were lysed and RhoA activity was measured. RhoA activity significantly decreases at 1, 4 and 6 hours (p<0.0001 vs. 0 hours, i.e. no alcohol; n=5). B. NHBE were exposed to 0, 25, 50 and 100mM alcohol for 4 hours and RhoA activity was measured. RhoA activity significantly decreases at all concentrations of alcohol (p<0.0001 vs. 0 mM media control; n=5).

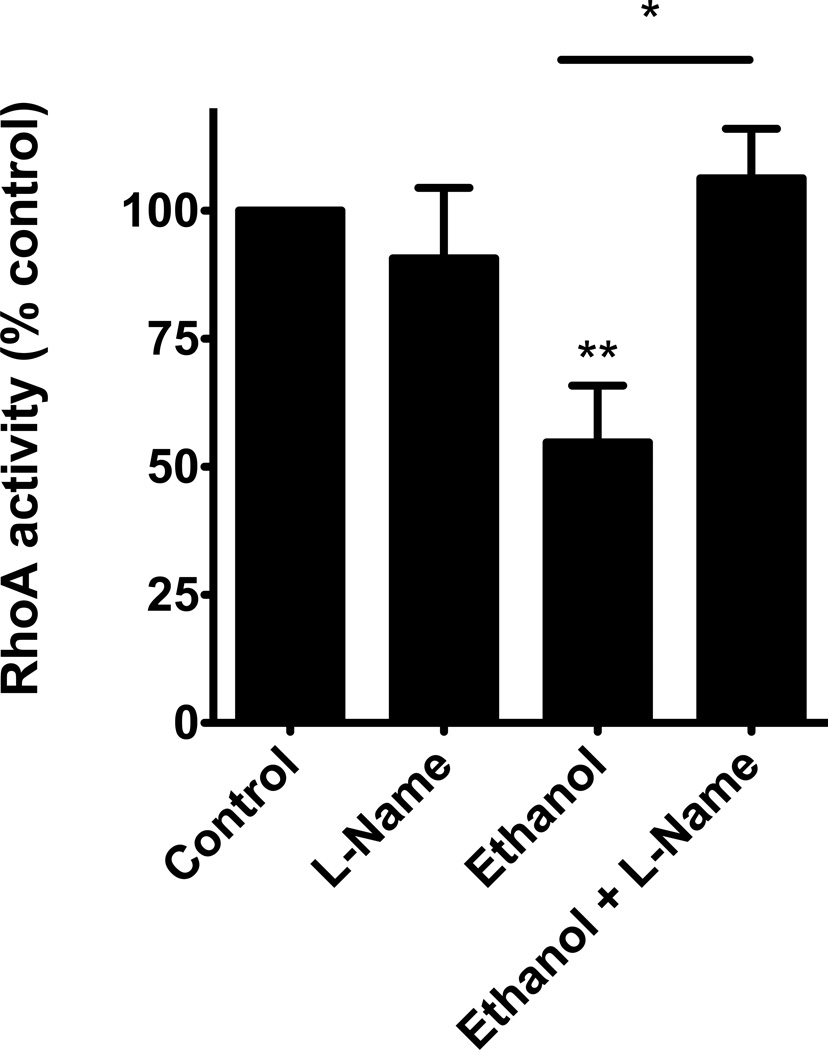

To test this hypothesis, we blocked the production of NO using the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor N(G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME). The cells were pretreated with 1µM L-NAME for 1 hour, then 100mM alcohol was added to the appropriate plates, while L-NAME remained. We noted that alcohol once again significantly decreased RhoA activity (p≤0.05) and L-NAME blocked alcohol’s decrease in RhoA activity (p≤0.02; n=5; Figure 3). In fact, the cells that were pre-treated with L-NAME, then exposed to alcohol were not statistically different from the control cells. These data suggest that NO production is essential to how alcohol diminishes RhoA activity.

Figure 3. Inhibiting Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS) with L-NAME, blocks the alcohol induced decrease in RhoA activity.

NHBE were pretreated for 1 hour with L-NAME (1 µM) then stimulated with 100mM alcohol for 4 hours. L-NAME blocks the alcohol-induced decrease in RhoA activity (*p≤0.02 vs. ethanol; **p≤0.05 vs. control; n=5).

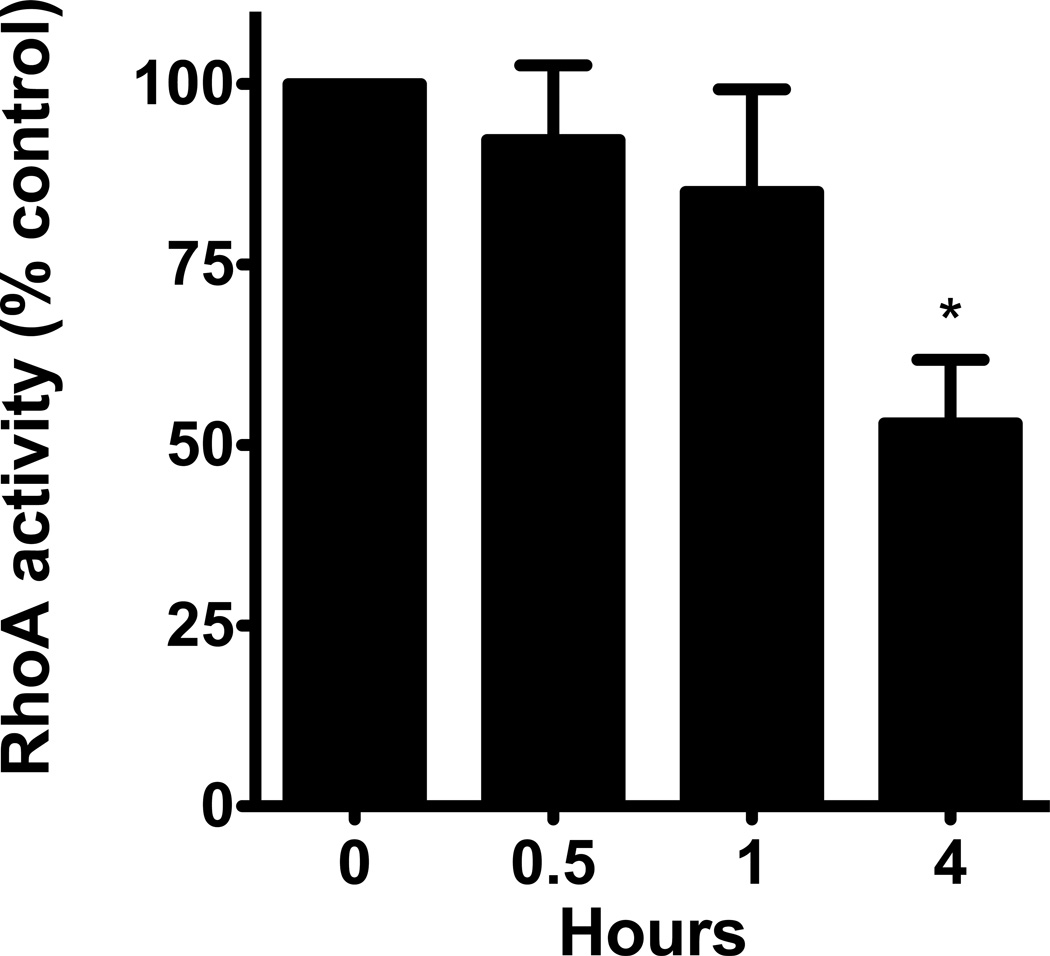

We were able to mimic alcohol’s effect on RhoA activity using sodium nitroprusside (SNP), a direct NO donor. Cells were exposed to 0.1µM SNP for 0.5, 1 and 4 hours. Similar to alcohol, we saw a significant decrease in RhoA activity at 4 hours (p≤0.03; n=5; Figure 4). There was no appreciable difference in RhoA activity at 0.5 or 1 hour. These data further support the idea that direct stimulation of NO can lead to a decrease in RhoA activity.

Figure 4. Sodium Nitroprusside (SNP), an NO donor, mimics the decrease in RhoA activity induced by alcohol.

NHBE were stimulated with 0.1µM SNP for 0–4 hours and RhoA activity was measured. SNP significantly decreases RhoA activity at 4 hours (p≤0.03 vs. 0 hours, i.e. no SNP; n=5).

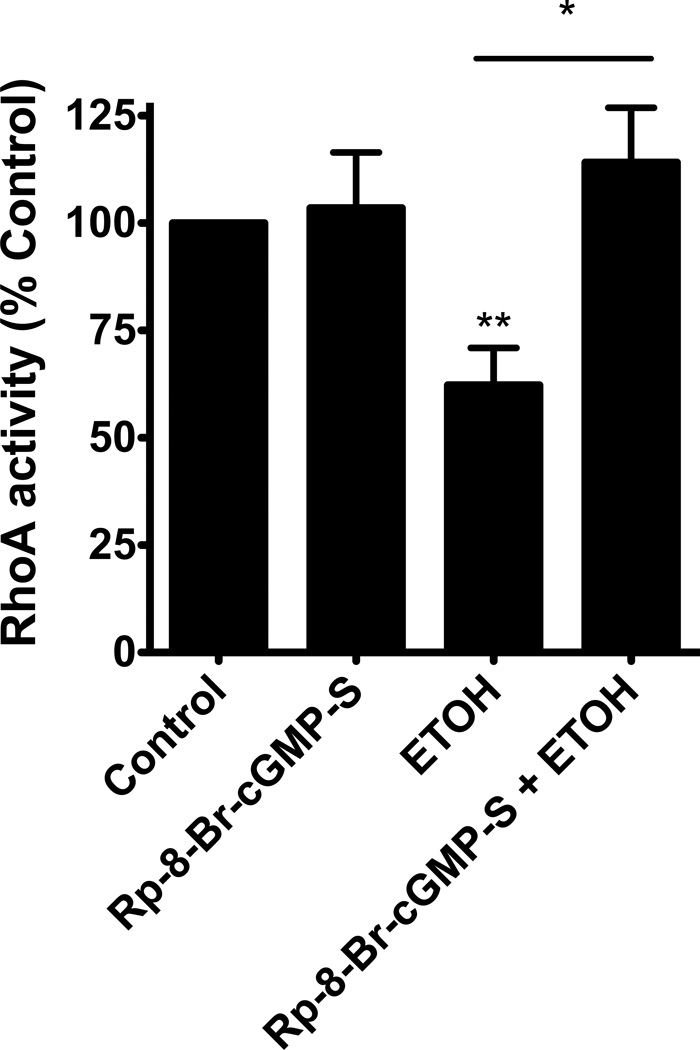

We hypothesized that NO was likely working through the second messenger cGMP to produce its effect on RhoA activity. To test this hypothesis, we pretreated the cells with the analogue antagonist of cGMP, Rp-8-Br-cGMPS, followed by alcohol exposure and assayed RhoA activity. Cells were pretreated with 100µM Rp-8-Br-cGMPS for 1 hour. 100mM alcohol was then added to the appropriate wells with the Rp-8-Br-cGMPS remaining. We observed that alcohol significantly decreased RhoA activity (p≤0.05; n=5; Figure 5) and Rp-8-Br-cGMPS inhibited alcohol’s decrease in RhoA activity (p≤0.02; n=5; Figure 5). This indicates that the cGMP activation of PKG likely plays a role in alcohol’s effect on RhoA activity. The RhoA activity of the cells pretreated with Rp-8-Br-cGMPS, and stimulated with alcohol was not different from control. These data suggest that cGMP/PKG also play a role in the regulation of RhoA activity in airway epithelial cells.

Figure 5. Inhibiting cGMP with the analogue antagonist Rp-8-Br-cGMPS blocks the alcohol-induced decrease in RhoA activity.

NHBE were pretreated with (100 µM) Rp-8-Br-cGMPS for 1 hour then stimulated with 100mM alcohol for 4 hours. Rp-8-Br-cGMPS was able to effectively block alcohol-induced decreases in RhoA activity (*p≤0.02 vs. ethanol; **p≤0.05 vs. control; n=5).

DISCUSSION

This set of experiments supports the hypothesis that alcohol diminishes RhoA activity through the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway in human airway epithelial cells. This decrease in RhoA activity potentially has widespread functional consequences for the cells including: impaired wound closure, ciliogenesis, tight junction regulation, actin cytoskeleton organization, smooth muscle contraction and apoptosis. Together, these impairments could weaken host defense and leave the cell vulnerable to infection and inflammation.

The in vitro model used mimics the way the airway epithelium is exposed to alcohol during binge drinking in vivo. A strength of our model is that we have used primary human cells to more closely approximate what happens in the human lung during a drinking binge. During the rapid alcohol ingestion that occurs with binge drinking, alcohol freely diffuses from the bronchial circulation directly through the airway epithelium where it vaporizes as it moves into the conducting airways (George et al., 1996). The vaporized alcohol can deposit back into the airway lining fluid to be released again into the airways during exhalation. This “recycling” of alcohol vapor results in constant exposure of the airway epithelium to high local concentrations of alcohol. The concentrations of alcohol in the lung are high enough that the alcohol vapor excreted into the airways forms the basis of the breath test used to estimate blood alcohol levels (Sisson, 2007; Hlastala, 1998).

The concentrations of alcohol used in this series of experiments are physiologically relevant. The 25mM exposure approximates 0.10% in vivo, which is just over the legal limit to drive. The 100mM exposure approximates severely intoxicated patients that are frequently seen in emergency rooms.

Little is known about how alcohol modulates RhoA activity in the airway epithelium and what consequences that may have on the basic functions of the airway epithelium. This manuscript defines how an acute exposure to alcohol modulates RhoA, and mechanistically how it occurs. This is important because alcohol has been shown to have varying effects on RhoA activity depending on the tissue type and chronicity of exposure. For instance, in the brain, chronic exposure to alcohol decreases RhoA activity in rat astrocytes (Martinez et al., 2007). In the liver, chronic alcohol feeding of rats had no effect on RhoA activation in the liver (Schaffert et al., 2006). In vascular smooth muscle, activation of the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway increased the activation of RhoA (Sauzeau et al., 2000).

In summary, alcohol and the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway have been shown to be closely involved with the regulation of RhoA activity. The regulation of RhoA activity seems to be tissue specific and also varies with the chronicity of exposure. In the experiments performed, we only looked at relatively short exposures to alcohol. It is possible that longer-term exposure to alcohol may have different effects on RhoA activity. Likewise, we only examined one cell type in the pulmonary compartment. It is likely that other cells such as alveolar macrophages may have different responses.

More investigation is required to further delineate how alcohol modulates RhoA activity in the airway epithelium. It is likely that chronic exposure to alcohol may have different effects on RhoA activity than seen with acute exposure. It is also possible that in vivo exposure to alcohol may have more complex effects on RhoA activity in the lung, given the many cell types that make up the pulmonary milieu. RhoA is likely only one of the many signaling molecules in the airway epithelium that is affected by alcohol. But given the quantity of cellular functions that RhoA participates in, it helps explain the pleiotropic effects that we see with alcohol exposure. It is also possible that the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway is not the only pathway that participates in alcohol’s modulation of RhoA. It is possible that reactive oxygen species and peroxynitrate also play a role. These possibilities require further study.

Overall, RhoA is an important regulator of the basic functions of the airway epithelium. In these experiments, we have shown that short-term alcohol exposure decreases RhoA activity in the airway epithelium through the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway. Alcohol’s impairment of RhoA signaling potentially leads to several detrimental changes in the airway epithelium. Impairment of RhoA signaling in the airway epithelium may be one of the mechanisms through which alcohol intake predisposes to increased pneumonia and bronchitis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to thank Art Heires for his expert assistance with cell imaging.

Sources of support:

K08AA019503-01 (KLB), R01AA017663-01 (TAW), R37AA8769-19 (JHS), VA Merit Review (TAW)

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey KL, Sisson JH, Romberger DJ, Robinson JE, Wyatt TA. Alcohol up-regulates TLR2 through a NO/cGMP dependent pathway. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:51–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Scally C, Fawzi A, Murray MP, Hill AT. Risk Factors for Complicated Parapneumonic Effusion and Empyema on Presentation to Hospital with Community Acquired Pneumonia. Thorax. 2009;64:592–597. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.105080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clements RT, Minnear FL, Singer HA, Keller RS, Vincent PA. RhoA and Rho-kinase dependent and independent signals mediate TGF-beta-induced pulmonary endothelial cytoskeletal reorganization and permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L294–L306. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00213.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Roux A, Cavalcanti M, Marcos MA, Garcia E, Ewig S, Mensa J, Torres A. Impact of alcohol abuse in the etiology and severity of community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2006;129:1219–1225. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.5.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai LP, Aryal AM, Ceacareanu B, Hassid A, Waters CM. RhoA and Rac1 are both required for efficient wound closure of airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L1134–L1144. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00022.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez-Sola J, Junque A, Estruch R, Monforte R, Torres A, Urbano-Marquez A. High alcohol intake as a risk and prognostic factor for community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1649–1654. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1995.00430150137014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fulcher ML, Gabriel S, Burns KA, Yankaskas JR, Randell SH. Well-differentiated human airway epithelial cell cultures. Methods Mol Med. 2005;107:183–206. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-861-7:183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George SC, Hlastala MP, Souders JE, Babb AL. Gas exchange in the airways. J Aerosol Med. 1996;9:25–33. doi: 10.1089/jam.1996.9.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hlastala MP. The alcohol breath test--a review. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:401–408. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joshi S, Guleria RS, Pan J, Bayless KJ, Davis GE, Dipette D, Singh US. Ethanol impairs Rho GTPase signaling and differentiation of cerebellar granule neurons in a rodent model of fetal alcohol syndrome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2859–2870. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6333-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jou TS, Schneeberger EE, Nelson WJ. Structural and functional regulation of tight junctions by RhoA and Rac1 small GTPases. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:101–115. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C, Zuo J, Janssen LJ. Regulation of airway smooth muscle RhoA/ROCK activities by cholinergic and bronchodilator stimuli. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:703–711. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00025506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez SE, Lazaro-Dieguez F, Selva J, Calvo F, Piqueras JR, Crespo P, Claro E, Egea G. Lysophosphatidic acid rescues RhoA activation and phosphoinositides levels in astrocytes exposed to ethanol. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1044–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore M, Marroquin BA, Gugliotta W, Tse R, White SR. Rho kinase inhibition initiates apoptosis in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;30:379–387. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0019OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moss M, Bucher B, Moore FA, Moore EE, Parsons PE. The role of chronic alcohol abuse in the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults. Jama. 1996;275:50–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moss M, Burnham EL. Chronic alcohol abuse, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S207–S212. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057845.77458.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan J, You Y, Huang T, Brody SL. RhoA-mediated apical actin enrichment is required for ciliogenesis and promoted by Foxj1. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1868–1876. doi: 10.1242/jcs.005306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saitz R, Ghali WA, Moskowitz MA. The impact of alcohol-related diagnoses on pneumonia outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1446–1452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sauzeau V, Le Jeune H, Cario-Toumaniantz C, Smolenski A, Lohmann SM, Bertoglio J, Chardin P, Pacaud P, Loirand G. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase signaling pathway inhibits RhoA-induced Ca2+ sensitization of contraction in vascular smooth muscle. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21722–21729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaffert CS, Todero SL, Casey CA, Thiele GM, Sorrell MF, Tuma DJ. Chronic ethanol treatment impairs Rac and Cdc42 activation in rat hepatocytes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1208–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sisson JH. Alcohol and airways function in health and disease. Alcohol. 2007;41:293–307. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sisson JH. Ethanol stimulates apparent nitric oxide-dependent ciliary beat frequency in bovine airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L596–L600. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.4.L596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sisson JH, Pavlik JA, Wyatt TA. Alcohol stimulates ciliary motility of isolated airway axonemes through a nitric oxide, cyclase, and cyclic nucleotide-dependent kinase mechanism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:610–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suadicani P, Hein HO, Meyer HW, Gyntelberg F. Exposure to cold and draught, alcohol consumption, and the NS-phenotype are associated with chronic bronchitis: an epidemiological investigation of 3387 men aged 53–75 years: the Copenhagen Male Study. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58:160–164. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.3.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wyatt TA, Forget MA, Sisson JH. Ethanol stimulates ciliary beating by dual cyclic nucleotide kinase activation in bovine bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1157–1166. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63475-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wyatt TA, Sisson JH. Chronic ethanol downregulates PKA activation and ciliary beating in bovine bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L575–L581. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.3.L575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wyatt TA, Spurzem JR, May K, Sisson JH. Regulation of ciliary beat frequency by both PKA and PKG in bovine airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L827–L835. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.4.L827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]