Abstract

Objective:

To determine the range of fluctuation in total lymphocyte counts (TLCs) in peripheral blood over a 4- to 7-year period in patients with MS receiving fingolimod (FTY720) and the relation between TLCs and T-cell subsets (CD4+, CD8+, CCR7+/−) that are differentially regulated in the lymph nodes by fingolimod.

Methods:

TLCs were measured every 3 months in patients (n = 23) receiving fingolimod for 4 to 7 years. T-cell subset (CD4+, CD8+, and CCR7+/−) analyses were performed on whole-blood samples and/or freshly isolated or cryopreserved mononuclear cells.

Results:

All serially studied patients had mean TLCs <0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L. In 30% of patients, 20% to 40% of TLCs were >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L vs mean 4.0% for “nonfluctuator” patients. Cross-sectional analysis indicated that TLCs of 0.2–0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L correlated with numbers of CD8+ effector (CCR7−) cells. For patients discontinuing therapy, TLCs between 0.6 and 1.0 × 109 lymphocytes/L were associated with a relative increase of CD4 T cells and reappearance of CCR7+ (CD4+ and CD8+) T cells. Analysis of cryopreserved mononuclear cell samples from patients receiving therapy with TLCs >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L indicated no differences in total CD4 or CD8+ T cells but increased proportion of CD4+CCR7+ T cells compared to samples with TLCs <0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L.

Conclusion:

Fluctuations of TLCs within 0.2–0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L in patients receiving fingolimod reflect changes in total CCR7−CD8+ effector cells, a population less regulated by this agent. Although less apparent than for patients discontinuing therapy, cells expected to be sequestered by this therapy may begin to re-emerge when TLC values are >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L.

Fingolimod (FTY720) decreases expression of sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptors on lymphocytes. This inhibits their egress from regional lymph nodes (LNs), resulting in peripheral blood lymphopenia.1 Lymphocyte trafficking between the peripheral circulation and LNs is regulated by a balance of homing signals, including those recognized by chemokine receptor CCR7, and egress signals mediated by S1P.1,2 Lymphocyte retention in LNs is most apparent for CCR7-expressing T cells (naive and central memory) and least for CCR7− effector memory cells3; the latter are more numerous within the CD8+ than the CD4+ population, accounting for their greater contribution to the remaining circulating lymphocyte pools.1,4,5 Phase III clinical trials with fingolimod included daily doses of 1.25 mg and 0.5 mg, but 0.5 mg is the currently approved dose.4 No differences in clinical or MRI efficacy outcomes were observed between doses. Although no significant concerns about infections were identified, recent reports raise issues regarding the impact of peripheral lymphopenia on susceptibility to infection, especially herpes virus–related.6

We address the range of fluctuation in total lymphocyte counts (TLCs) in peripheral blood in patients receiving fingolimod for up to 7 years and relate this to T-cell populations (CD4+, CD8+, CCR7+/−) whose egress from the LNs is differentially regulated by CCR7/S1P-related signals. We compare this relation of TLCs and T-cell subsets with that found in individuals who reconstitute their peripheral lymphocyte pool while temporarily discontinuing therapy.

METHODS

Serial studies of TLCs.

TLCs of patients participating in extension phases of the Novartis 2201 (5.0 mg or 1.25 mg vs placebo)7 and 2302 (1.25 mg or 0.5 mg vs placebo) studies8 were measured on whole-blood samples every 3 months for up to 7 years (n = 9) and 4 years (n = 14), respectively, by standard commercial labs. Trial entry criteria required all patients to have a normal range of TLCs (1.4–4.0 or 0.8–2.8 × 109 lymphocytes/L). During the extension phase, patients were placed on a 1.25-mg or 0.5-mg daily dose as indicated in figure 1. Patients were categorized in “fluctuator” vs “nonfluctuator” subgroups based on the percentage of their TLC measurements exceeding 0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L. No patient had a mean TLC >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L. Patients with an individual standard deviation (SD) of TLCs larger than the SD of TLCs for the whole cohort were found to have >10% (20%–40%) of TLCs >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L whereas patients with a below average SD for TLCs had <10%.

Figure 1. Serial TLCs in fingolimod-treated patients.

Fluctuations in total lymphocyte counts (TLCs) in individual patients receiving fingolimod. For each cohort (studies 2201 and 2302), patients are subgrouped as “fluctuators” or “nonfluctuators” as defined in the results section. (A, C) Fluctuators in cohort 2201 and 2302, respectively. (B, D) Nonfluctuator patients from the same cohorts. Extension phase for study 2201 was initiated (month 0) with 5.0 mg or 1.25 mg of fingolimod daily; all patients were subsequently switched to 1.25-mg and then 0.5-mg dose as indicated. Extension phase for study 2302 was initiated with 1.25 mg or 0.5 mg of fingolimod daily; all patients were subsequently switched to 0.5-mg dose as indicated. The table provides mean values for TLCs for the total cohort and subgroups (fluctuator and nonfluctuator patients) in each study.

Lymphocyte subset analyses.

Cross-sectional subset analyses were performed on whole-blood samples from all patients continuing in the extension trial (4 were tested twice), and an additional 4 patients receiving therapy as part of clinical practice (n = 31 total samples). Controls included healthy volunteers and untreated patients with MS (n = 20). T cells were analyzed in whole-blood specimens by immunostaining with CD4-FITC, CD8-PerCP, and CCR7-AlexaFluor647 (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) antibodies. Data were acquired using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Similar analyses were performed on patients who transiently discontinued therapy because of clinical side effects (e.g., headache, pharyngitis), as well as on mononuclear cells recovered from cryopreserved samples that were collected during the trial.9

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The McGill University ethics committee approved all studies. All patients provided informed written consent.

Statistical analysis.

Patient subgroups were compared using an unpaired t test with Welch correction.

RESULTS

Serial TLC analyses.

Data of the 23 patients comprising the extension phase cohorts are provided in figure 1. Overall, 88.9% of the TLCs were in the range of the 0.2–0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L with no significant differences between the 2201 (88.1%) and 2302 (89.8%) cohorts. Although no patient had a mean TLC >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L, there was an apparent difference among patients regarding the extent of fluctuations in their serial TLCs. Seven patients, referred to as fluctuators, had between 20% and 40% of their individual TLCs outside the 0.2–0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L range (mean 27.3%) vs mean 4.0% for nonfluctuators (p < 0.001). As shown in figure 1, A and C, fluctuators were observed in both the 2201 (3 of 9 patients) and 2302 (4 of 14) cohorts and with both the 0.5-mg and 1.25-mg fingolimod dosages. Mean TLC was significantly higher in the overall fluctuator vs nonfluctuator groups (p < 0.01). Data comparing the demographic and clinical features of the 2 subgroups are provided in the table. Relapses were recorded in 2 of the 7 fluctuators and 7 of 16 nonfluctuators.

Table.

Comparison of demographics and clinical features of fluctuator and nonfluctuator patients

Relation of T-cell subset and TLCs <0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L.

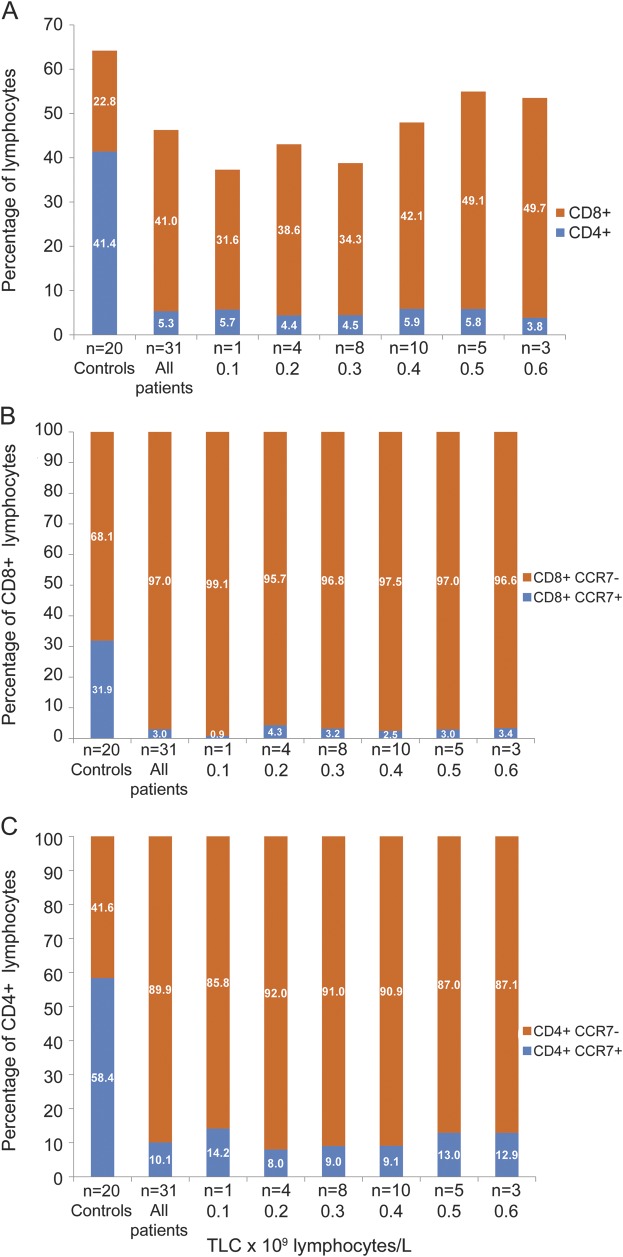

Although the 31 whole-blood samples included in our cross-sectional T-cell subset analysis were obtained from fluctuator and nonfluctuator subgroups, all had TLCs <0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L at collection time. The CD8 to CD4 T-cell ratio was increased compared with controls (8:1 vs 1:2 for controls, n = 20) (figure 2). This increased ratio was even more apparent in patients with TLCs of >0.4 × 109 lymphocytes/L (10:1) compared to those with TLCs of <0.4 × 109 lymphocytes/L (7:1). The proportion of CCR7+ cells in both the CD8+ (3.0% ± 2.0%) and CD4+ (10.1% ± 4.2%) T-cell subsets was significantly reduced compared with control values (33.1% ± 13.5% for CD8+ T cells, p < 0.001; 60.1% ± 11.1% for CD4+ T cells, p < 0.001). Thus, over this TLC range, the CD8+CCR7− population remained the dominant contributor to the T-cell pool (>85%).

Figure 2. Lymphocyte subset analysis in whole blood of fingolimod-treated patients.

Cross-sectional analysis of whole-blood samples of patients receiving therapy showing mean percentage CD8+ and CD4+ lymphocytes (A), CD8+CCR7+ and CCR7− cells (B), and CD4+CCR7+ and CCR7– cells (C) in relation to total lymphocyte counts (TLCs) in fingolimod-treated patients and controls.

Relation of T-cell subset and TLCs (0.6–1.0 × 109 lymphocytes/L) in patients discontinuing therapy.

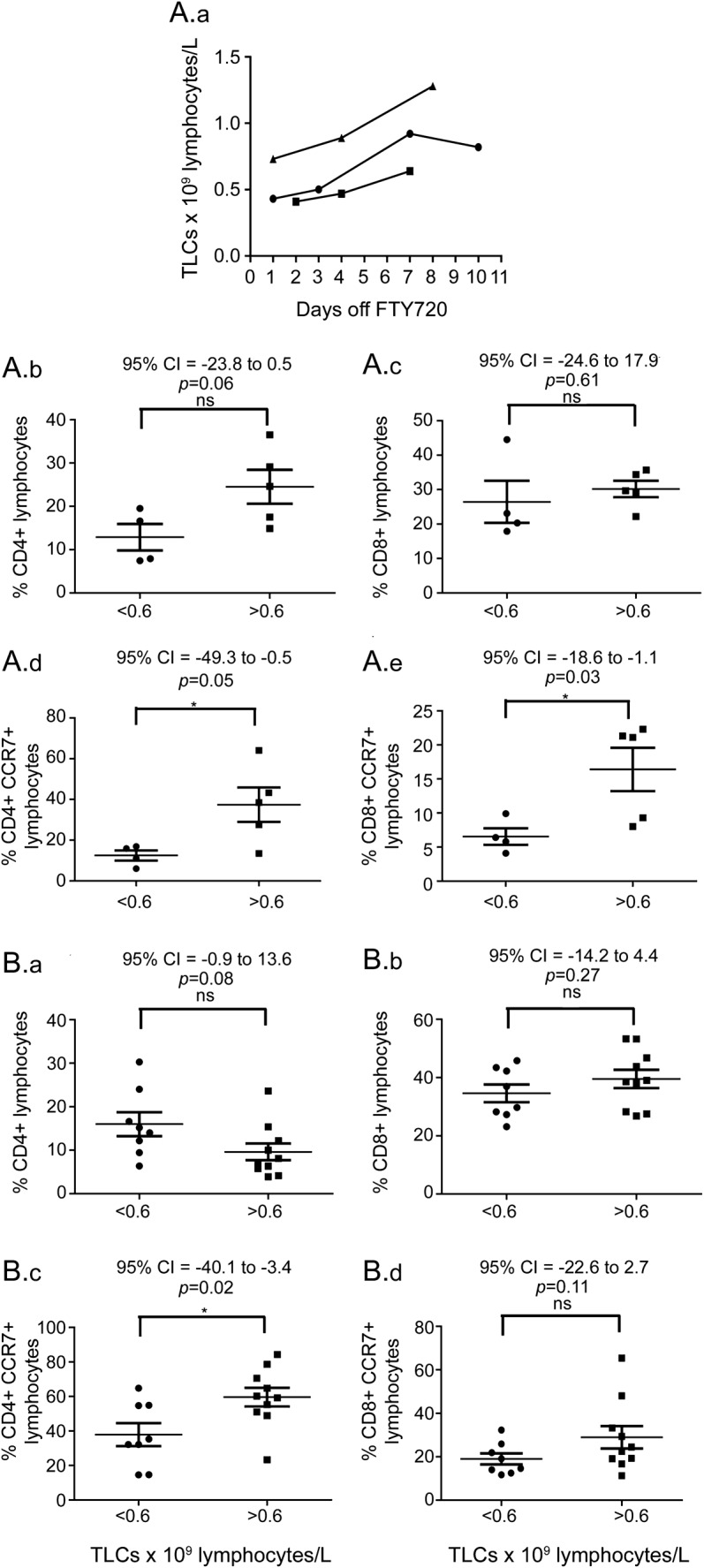

These whole-blood sample data were derived from 3 individuals discontinuing therapy (figure 3A). For the 5 available samples with TLCs of 0.6–1.0 × 109 lymphocytes/L, mean percentage total CD4+ T cells (24.5% ± 3.9%) was increased compared with the 4 available samples with TLCs <0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L from these same donors (12.9% ± 3.1%, p = 0.06). Total percentage CD8+ T cells was not different (30.2% ± 2.4% and 26.5% ± 6.1%). The mean proportion of CCR7+ cells in the CD4+ (37.4% ± 8.4%) and CD8+ (16.4% ± 3.2%) T-cell populations for TLCs >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L was increased compared with CD4+ (12.5% ± 2.5%) and CD8 (6.6% ± 1.2%) T cells for TLCs <0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L (all p < 0.05).

Figure 3. Lymphocyte subset analyses.

(A) Analysis of whole-blood samples from patients discontinuing fingolimod (FTY720) therapy. (A.a) Serial total lymphocyte counts (TLCs) in 3 individuals discontinuing fingolimod therapy. Comparison of percentage total CD4+ T cells (A.b), percentage total CD8+ T cells (A.c), percentage CD4+CCR7+ T cells (A.d), and percentage CD8+CCR7+ T cells (A.e) between TLC samples with values <0.6 and >0.6 (but <1.0) × 109 lymphocytes\L. (B) Lymphocyte subset analysis in cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples from fingolimod-treated patients. Comparison of percentage total CD4+ T cells (B.a), percentage total CD8+ T cells (B.b), percentage CD4+CCR7+ T cells (B.c), and percentage CD8+CCR7+ T cells (B.d) between TLC samples with values <0.6 and >0.6 (but <1.0) × 109 lymphocytes\L. CI = confidence interval; ns = not significant.

Relation of T-cell subset and TLCs >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L in patients receiving long-term therapy.

These data were derived from 10 cryopreserved samples with TLCs on the collection date of >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L and compared with 8 samples with TLCs of <0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L (figure 3B). Samples from 4 donors were included in both groups. For samples with TLCs >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L, mean percentage total CD4+ (9.6% ± 1.9%) and CD8 (39.5% ± 3.1%) T cells did not differ from samples with TLCs <0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L (16.0% ± 2.8% for CD4, 34.6% ± 3.0% for CD8). The mean proportion of CCR7+ cells in the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations was increased in the TLCs >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L samples (CD4+CCR7+ 37.9% ± 6.6% vs 59.6% ± 5.4%, p = 0.02; CD8+CCR7+ 19.0% ± 2.6% vs 28.9% ± 5.2%, p = 0.1).

DISCUSSION

This study indicates that at both the 0.5-mg and 1.25-mg doses of fingolimod, up to 30% of patients have repeated fluctuations in their TLCs to values >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L. However, no patient had a mean TLC >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L. Differences in TLCs did not correlate with serum drug levels provided by Novartis. We did not identify any link between fluctuations in TLCs and clinical disease activity or serious adverse events. Our cross-sectional T-cell subset analysis from patients with TLCs in the 0.2 to 0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L range showed that CD8+ effectors (CD8+CCR7−) were the dominant T-cell population throughout this range. This is consistent with observations that such CCR7− cells are less regulated by S1P gradients. CD4+ and CD8+ cells accounted for approximately 45% of the total lymphocyte population; the remaining cells would predominantly be natural killer cells.10

For patients with TLCs between 0.6 and 1.0 × 109 lymphocytes/L when withdrawing from therapy, there was reappearance of cells (CD4+ T cells, CCR7+ T cells) expected to be sequestered by the therapy and implicated both in disease pathogenesis and host defense. The finding of this rapid reconstitution of CCR7+ cells, a population that includes Th17 central memory cells,1 raises caution about temporary drug holidays used to evaluate possible drug-induced secondary effects or to permit transition to other therapies. Although the profile of lymphocytes in patients with TLCs >0.6 × 109 lymphocytes/L while receiving therapy does not recapitulate that of patients discontinuing therapy, our results suggest that cells expected to be sequestered by this therapy (CCR7+) are beginning to re-emerge.

GLOSSARY

- LN

lymph node

- S1P

sphingosine 1-phosphate

- TLC

total lymphocyte count

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D. Henault has participated in study concept and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data. L. Galleguillos has participated in acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data. C. Moore has participated in analysis and interpretation of data and in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. T. Johnson has participated in analysis and interpretation of data. A. Bar-Or has participated in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. J. Antel is responsible for study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

Supported by a research grant from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc. to McGill University (Jack Antel). David Henault was the recipient of a summer studentship from the endMS Research and Training Network Canada.

DISCLOSURE

D. Henault, L. Galleguillos, C. Moore, and T. Johnson report no disclosures. A. Bar-Or has participated as a speaker at meetings sponsored by, received consulting fees and/or received grant support from: Amplimmune, Bayhill Therapeutics, Berlex/Bayer, Biogen Idec, BioMS, DioGenix, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Genzyme, GSK, Guthy-Jackson/GGF, EMD Serono, MedImmune, Mitsubishi Pharma, Novartis, Ono Pharma, Receptos, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva Neuroscience, and Wyeth. J. Antel has received research support from Novartis and from CIHR (industry partnership program) related to fingolimod. He has served as a consultant and/or on safety monitoring boards for Novartis, Biogen IDEC, Sanofi-Aventis, TEVA, EMD Serono, Genzyme, and Cleveland Clinic Foundation. He serves as coeditor of the Multiple Sclerosis Journal. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mehling M, Johnson TA, Antel J, Kappos L, Bar-Or A. Clinical immunology of the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2011;76(8 suppl 3):S20–S27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graler MH, Goetzl EJ. The immunosuppressant FTY720 down-regulates sphingosine 1-phosphate G-protein-coupled receptors. FASEB J 2004;18:551–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moschovakis GL, Forster R. Multifaceted activities of CCR7 regulate T-cell homeostasis in health and disease. Eur J Immunol 2012;42:1949–1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovarik JM, Schmouder R, Barilla D, Riviere GJ, Wang Y, Hunt T. Multiple-dose FTY720: tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and lymphocyte responses in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 2004;44:532–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson TA, Lapierre Y, Bar-Or A, Antel JP. Distinct properties of circulating CD8+ T cells in FTY720-treated patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2010;67:1449–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourdette D, Gilden D. Fingolimod and multiple sclerosis: four cautionary tales. Neurology 2012;79:1942–1943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kappos L, Antel JP, Comi G, et al. Oral fingolimod (FTY720) for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1124–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kappos L, Radue EW, O'Connor P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:387–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darlington PJ, Touil T, Doucet JS, et al. Diminished Th17 (not Th1) responses underlie multiple sclerosis disease abrogation after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Neurol 2013;73:341–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson TA, Evans BL, Durafourt BA, et al. Reduction of the peripheral blood CD56(bright) NK lymphocyte subset in FTY720-treated multiple sclerosis patients. J Immunol 2011;187:570–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]