Abstract

Up to 80% of patients with severe posttraumatic stress disorder are suffering from “unexplained” chronic pain. Theories about the links between traumatization and chronic pain have become the subject of increased interest over the last several years. We will give a short summary about the existing interaction models that emphasize particularly psychological and behavioral aspects of this interaction. After a synopsis of the most important psychoneurobiological mechanisms of pain in the context of traumatization, we introduce the hypermnesia–hyperarousal model, which focuses on two psychoneurobiological aspects of the physiology of learning. This hypothesis provides an answer to the hitherto open question about the origin of pain persistence and pain sensitization following a traumatic event and also provides a straightforward explanatory model for educational purposes.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, chronic pain, hypermnesia, hypersensitivity, traumatization

Video abstract

Previous models of interaction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is defined as a mental disorder that may occur after the experience of a traumatic event. According to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), PTSD is characterized by three distinct clusters of symptoms, consisting of 1) re-experiencing of the traumatic event (eg, in thoughts or dreams); 2) avoidance of reminders of the event and emotional numbing; and 3) hyperarousal (eg, irritability and sleep problems).1 Many persons traumatized by war, accident victims, people with a history of sexual abuse, or victims of torture suffer from both PTSD and chronic pain. Study results on war veterans with PTSD show comorbidity rates with chronic pain of 66% to 88%.2,3 Olsen et al report a prevalence of chronic pain of up to 75% in victims of torture.4 Several studies have been able to show that traumatizing events can generally be regarded as predictive of pain chronification.5,6

The relationship between psychological sequelae of traumatization and chronic pain is bidirectional and complex. Most of the existing theoretical models emphasize psychological or behavioral aspects (see Table 1): the shared vulnerability model, for instance, focuses on the presence of heightened anxiety sensitivity in individuals affected by PTSD and chronic pain, suggesting a possible common basis for vulnerability.7 The mutual maintenance model goes even further by positing additional common features (eg, depressive symptoms) and emphasizing that both disorders can perpetuate each other in a sufferer’s experience.8 At the behavioral level, the perpetual avoidance model demonstrates that avoidance behavior and catastrophizing thinking in particular tend to perpetuate symptoms in both people with chronic pain disorders and those with PTSD.9 Focusing on the importance of the stress physiology, McLean et al’s model also integrates neurobiological and neuroendocrine origins of the phenomenology.10

Table 1.

Compilation of previous models of interaction between traumatization and chronic pain

| Model | Central aspect of interaction | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Shared vulnerability model | The evidence of heightened anxiety sensitivity in individuals affected by posttraumatic stress disorder as well as in individuals with chronic pain is assumed to be a common etiopathogenetic vulnerability factor | 7 |

| Mutual maintenance model | Common features and symptoms (eg, depressive symptoms, sleep disorder) maintain both diagnoses mutually in the sufferer’s experience. | 8 |

| Perpetual avoidance model | Typical avoidance behavior and catastrophizing thinking tend to perpetuate symptoms in both people with chronic pain disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. | 9 |

| McLean et al’s model | Common biological and endocrine features originate in the overlapping phenomenology of trauma-associated stress disorder and chronic pain symptoms. | 10 |

Our hypermnesia-hyperarousal model, introduced herein, postulates that pain persistence and pain sensitization following a traumatizing event are neurophysiological reactions connected to two mechanisms of learning physiology. This non-dualistic manner of explanation has a destigmatizing and clarifying impact also for the patient’s education.

Clinical and physiological background

Pain sensitization

Pain disorders in traumatized persons often have in common that they are not or not sufficiently explained by structural somatic injury. This fact could mislead an observer to rush to the conclusion that the pain reported by a patient is of “virtual” origin. In order to be able to understand this type of pain disorder, one must differentiate between the somatic injury that triggers pain and the neuroperceptive process of perceiving pain. When traumatization occurs, both of these are generally affected: many traumatized persons suffer from a local physical trauma as well as from a massive disturbance of the structures processing pain stimuli. Generally, every persistent or severe local physical injury can cause a neurofunctional enhancement of the pain-transmitting structures.11,12 This mechanism of chronification is, for example, accompanied by an enhancement of synaptic pain transmission at the spinal level of the central nervous system, which is generally referred to as “central sensitization.” Further, it has to be stressed that certain local injuries themselves can directly provoke persistent neurogenic pain. A typical example of neuropathic pain is burning sensations of the soles after flogging torture (falanga).13 Finally, animal experiences have shown that repeated high stress can itself lead to peripheral enhancement of pain stimuli: under the influence of the stress hormones (cortisol and epinephrine), the intracellular signal pathway in the primary afferent nociceptive nerve fibers (nociceptors) is changed and leads to enhancement and prolongation of pain signals.14

As well as originating from peripheral and spinal sensitization, as mentioned above, increased pain sensitivity can also be of cerebral origin. The continued and intense experience of stress leads to an increase in pain sensitivity on the cerebral level via multiple neurofunctional mechanisms.15–19 The resulting sensitization is a form of implicit learning that has been demonstrated in individual nerve cells as well as in entire organisms.20,21 Sensitization brings about an increased reaction towards painful stimuli (hyperalgesia) and, possibly, an increased reaction even towards neutral stimuli (eg, allodynia).22,23 At the neurotransmitter level, traumatization is associated with massive glutamate release induced by the amygdala.24 Glutamate is a classical neuronal stimulus enhancer that generally plays a role in the sensitization and long-term potentiation (chronification) of synaptic signals.25

Imprinting

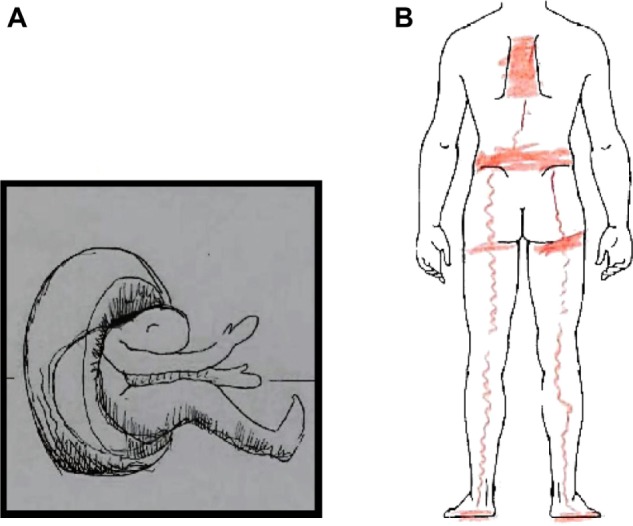

Imprinting is an extremely long-lasting and robust form of preserving experiences. As early as in the late 1980s, it was assumed that excessive neuroendocrine stress responses may lead to an overconsolidated memory of trauma.26 Furthermore, imprinting is the basis for subsequent mnestic reactivations. Pain experiences in traumatized individuals are typically reactivated by stimuli associatively linked to the traumatic experience. The involved associative chains work both ways: trauma associations can evoke pain experiences and pain experiences can evoke trauma associations.27 In clinical terms, we distinguish two types of pain-associated imprints: pain intrusions (or pain flashbacks) are situationally triggered and generally fade away again.28,29 They refer to painful somatic experiences related to the initial traumatizing context and come to be realized in the conscious mind in an almost realistic manner. Chronic memory pain, on the other hand, is characterized by its persistent nature. Often there is a direct anatomical relationship between chronic memory pain to the initial pain event.29 The central nervous structures of pain processing appear to irreversibly freeze the memory of the primary pain impression (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Drawings of a 54-year-old woman who was politically persecuted and tortured over several weeks.

Notes: (A) The drawing shows the woman’s fixation in a wheel, a frequently used method of torture. (B) The marks correspond to the initial physical pain caused by the torture. However, upon referral 5 years later, these pain locations could no longer be explained by structural anatomical lesions, but only by a kind of a sensitization and memory pain.

Anxiety

Anxiety is one of the most decisive factors in relation to the risk of traumatization. Pain and anxiety are physiologically closely related. Whereas anxiety is a psychophysiological alarm function that signals a situational threat to integrity, pain is a psychophysiological alarm function that signals a physical threat to integrity. It has been shown even in animal experiments that, with respect to neuroperception, an additive effect takes place if both systems are activated.30,31 Neugebauer et al imply a relationship with some direct modulation by the laterocapsular division of the central nucleus of the amygdala, assuming this to be of major importance in traumatogenic pain genesis.32

Pain numbing

Besides the aforementioned pain-intensifying mechanisms related to trauma, there are also mechanisms of endogenous–reactive pain numbing in situations of serious threat: trauma-associated situations exceeding the maximal subjective tolerance give rise to dissociative processes. The latter can be followed by clouding of consciousness, for example, through the effect of endorphins (self-narcotization) or by emotional and physical numbness (auto-anesthesia).33,34 These neurofunctional losses reflect an attempt to turn a desperate situation that is intolerable into one that is survivable. Possibly, those investigations showing also reduced cutaneous pain sensitivity in PTSD suggest an involvement of such dissociative mechanisms.35,36

Hyperalgesia and cutaneous pain-numbing mechanisms do not mutually exclude each other, since intense pain is typically a prerequisite for the triggering of dissociative processes. Typically, chronic pain and reduced superficial sensitivity appear concomitantly.37,38

The hypermnesia–hyperarousal model

The above-described neurophysiological aspects form the theoretical basis of the following hypothesis. This hypothesis states that chronic “unexplained” pain of traumatized people originates directly in a hypermnestic and sensitized pain perception.

In numerous everyday situations involving minor threats, hypermnesia and sensitization prove to be valuable and protective mechanisms: threat-induced hypermnesia is meant to make sure that an individual will, in future, recognize a particular danger again, in order to avoid it. Threat-induced hyperexcitability and sensitization are supposed to detect a potential hazard as early as possible (see Table 2). In a developmental context, it may have been advantageous for vertebrates if situations of external threat were strongly imprinted in an individual’s mind, to result in a state of sensitization. However, if intense threat-related memory imprinting occurs, it seems that not only external impressions but also internal perceptions (eg, pain) are strongly memorized. The intense hypermnesia of trauma-associated pain experiences thus becomes the basis for memory-related pain, whereas the trauma-induced hyperexcitability forms the basis for hyperalgesia and allodynia.

Table 2.

Preservation and sensitization reaction patterns of the central nervous system in processing external threatening stimuli

| Example | Hypermnesia (intention: protection by recognition)

|

Hyperarousal (intention: protection by early detection)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Imprinting | Memory | Sensitization | |

| Preservation/chronification of an impression. | Associative realization. | Increased sensitivity to trauma-associated stimuli. | |

| Traumatizing experience of violence in a mugging at night by a passer-by wearing a hat. | From now on, the night will be memorized as a particularly threatening time. If possible, the person will only leave the house at daytime in future. | Every person wearing a hat, even on TV, will automatically conjure up the mugging that happened. | State of hyperalertness when walking through the neighborhood. Observing every potentially dangerous person walking by. |

According to the hypermnesia–hyperarousal model, post-traumatic pain persistence is an undesired and excessive “side effect” of these two normally self-protective mechanisms of learning physiology.

After a traumatic event, many people suffer not only from ongoing pain but from ongoing fear and ongoing stress as well. One might assume that the trauma-induced impressions of high anxiety and existential stress are also modified in the same manner as pain experience: a fixation and sensitization of anxiety and stress lead analogously to chronification and decreased tolerance thresholds of these two states. Table 3 further illustrates these two aspects with examples.

Table 3.

Preservation and sensitization reaction patterns of the central nervous system in processing internal trauma-associated stimuli

| Example | Hypermnesia (intention: protection by recognition)

|

Hyperarousal (intention: protection by early detection)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Imprinting | Memory | Sensitization | |

| Preservation/chronification of an impression | Associative realization | Increased sensitivity to trauma-associated stimuli | |

| Pain suffered in torture | The pain experience will typically be memorized in those parts of the body in which physical traumatization occurred; so-called chronic “memory pain” | Situationally triggered somatosensory pain flashbacks | Increased pain sensitivity with generalized or local hyperalgesia and allodynia |

| Anxiety related to torture | Subsequent chronic anxiety state | Specific mnestically triggered anxiety attacks | Excessive decreased anxiety thresholds in everyday situations that can be associated with specific phobias, eg, at the sight of people in uniform |

| Stress related to torture | State of sustained psychophysical stress | Stress states with paroxysmal onset following trauma-associated stimuli | Hypersensitivity to stress in everyday situations; stress intolerance (cognitive and emotional) with progressive loss of performance |

First evaluations and conclusion

The risk of suffering from trauma-induced sequelae such as PTSD depends on many internal and external factors. We would like to stress that the pathology of posttraumatic pain is often multicausal. It is also important to bear in mind structural–nociceptive and neuropathic facets.38–40 According to our experience, however, the hypermnesia–hyperarousal model provides a plausible hypothesis for explaining aspects of pain that cannot be explained by structural damage, but that originate from altered pain-processing in the central nervous system. It offers a plausible neurofunctional assumption for explaining the occurrence of pain chronification and pain sensitization with learning physiology.

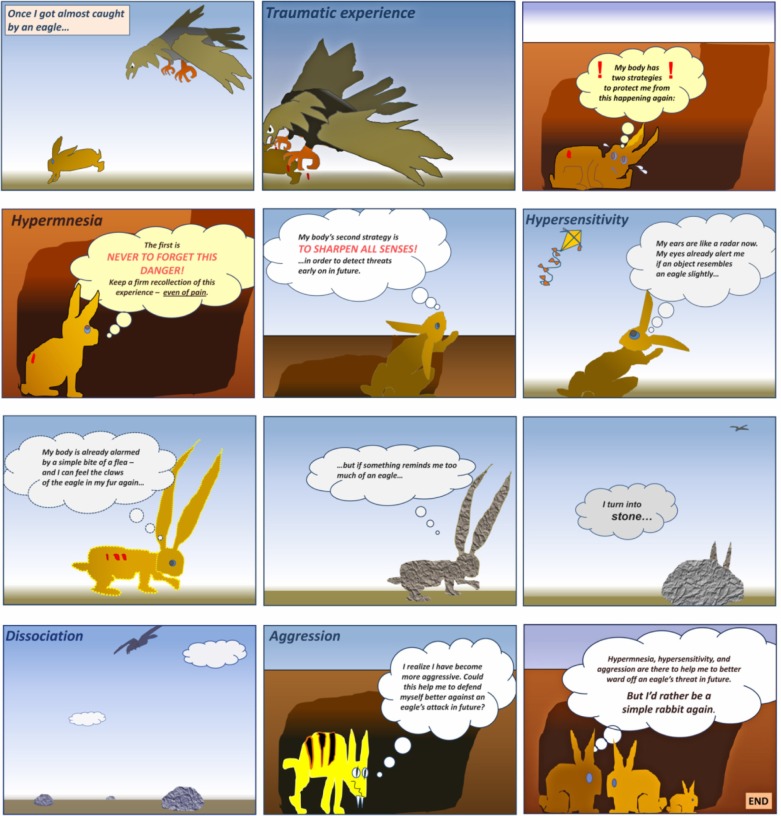

A prospective experimental study on how pain is imprinted on people’s memories under intense experience of stress can, for ethical reasons, not be performed. However, animal models and many retrospective analyses of numerous human individuals allude to such mechanisms.14,15,27–29,38 Generally, the impact of a theoretical model is not only shown in its scientific reliability but also in its pragmatic usefulness in everyday application. Our clinical experiences and patients’ feedback motivate us to further investigate the therapeutic effect of this explanatory theory. For instance, a potential therapeutic effect of an educative intervention on alleviating posttraumatic stress symptoms and other psychometric key variables could be verified against a wait-list control group. To this end, easy-to-grasp educational material for patients have been developed (see Figure 2). We consider that the psychotherapeutically desirable step of reframing is strongly supported by our model: for patients, it is therapeutically very meaningful to conceive trauma-associated sequelae as a “normal” reaction to an extremely “abnormal” event. If a patient arrives at an understanding that their situation is not the result of personal failure but is rather an expected consequence of excessive auto-protective strategies of the nervous system, this can open the way to a vital reassessment of their suffering.

Figure 2.

The hypermnesia–hyperarousal model: easily understandable educational material.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Annette Kocher and Jean Pierre Geri for their editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poundja J, Fikretoglu D, Brunet A. The co-occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and pain: is depression a mediator? J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:747–751. doi: 10.1002/jts.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shipherd JC, Keyes M, Jovanovic T, et al. Veterans seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: what about comorbid chronic pain? J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:153–166. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2006.06.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen DR, Montgomery E, Bøjholm S, Foldspang A. Prevalence of pain in the head, back and feet in refugees previously exposed to torture: a ten year follow-up study. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:163–171. doi: 10.1080/09638280600747645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dirkzwager AJ, van der Velden PG, Grievnik L, Yzermans CJ. Disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:435–440. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318052e20a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koleck M, Mazaux JM, Rascle N, Bruchon-Schweitzer M. Psycho-social factors and coping strategies as predictors of chronic evolution and quality of life in patients with low back pain: a prospective study. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asmundson GJ, Coons MJ, Taylor S, Katz J. PTSD and the experience of pain: research and clinical implications of shared vulnerability and mutual maintenance models. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:930–937. doi: 10.1177/070674370204701004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharp TJ, Harvey AG. Chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: mutual maintenance? Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21:857–877. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liedl A, Knaevelsrud C. PTSD and chronic pain: development, maintenance and comorbidity – a review. Schmerz. 2008;22:644–651. doi: 10.1007/s00482-008-0714-0. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLean SA, Clauw DJ, Abelson JL, Liberzon I. The development of persistent pain and psychological morbidity after motor vehicle collision: integrating the potential role of stress response systems into a biopsychosocial model. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:783–790. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000181276.49204.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandkühler J. Neurobiology of spinal nociception: new concepts. Prog Brain Res. 1996;110:207–224. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62576-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woolf CJ, Salter MW. Neuronal plasticity: increasing the gain in pain. Science. 2000;288:1765–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prip K, Persson AL. Clinical findings in men with chronic pain after falanga torture. Clin J Pain. 2008;2:135–141. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31815aac36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khasar SG, Dina OA, Green PG, Levine JD. Sound stress-induced long-term enhancement of mechanical hyperalgesia in rats is maintained by sympathoadrenal catecholamines. J Pain. 2009;10:1073–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivimäki M, Leino-Arjas P, Virtanen M, et al. Work stress and incidence of newly diagnosed fibromyalgia: a prospective cohort study. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felliti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of child abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egle UT, Hardt J, Nickel R, Kappis B, Hoffmann SO. Long-term effects of adverse childhood experiences—Actual evidence and needs for research. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2002;48:411–434. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2002.48.4.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McBeth J, Morris S, Benjamin S, Silman AJ, Macfarlane GJ. Associations between adverse events in childhood and chronic widespread pain in adulthood: are they explained by differential recall? J Rheumatol. 2001;28:2305–2309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imbierowicz K, Egle UT. Childhood adversities in patients with fibromyalgia and somatoform pain disorders. Eur J Pain. 2003;7:113–119. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(02)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandel ER. Auf der Suche des Gedächtnis. Munich: Siedler Verlag; 2006. In search of memory: The ermergence of a new science and mind. German. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hölzl R, Kleinböhl D, Huse E. Implicit operant learning of pain sensitization. Pain. 2005;115:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yunus MB. Central sensitivity syndromes: a new paradigm and group nosology for fibromyalgia and overlapping conditions, and the related issue of disease versus illness. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37:339–352. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egloff N, von Känel R. [Comment on rule of thumb 7. Groaning during blood pressure determination: suspected somatoform pain]. Kommentar zu Faustregel 7. Praxis. 2010;99:26–28. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nair J, Singh Ajit S. The role of the glutamatergic system in posttraumatic stress disorder. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(7):585–591. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900016862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blair HT, Schafe GE, Bauer EP, Rodrigues SM, LeDoux JE. Synaptic plasticity in the lateral amygdala: a cellular hypothesis of fear conditioning. Learn Mem. 2001;8:229–242. doi: 10.1101/lm.30901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitman RK. Post-traumatic stress disorder, hormones, and memory. Biol Psychiatry. 1989;26:221–223. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(89)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whalley MG, Farmer E, Brewin CR. Pain flashbacks following the July 7, 2005 London bombings. Pain. 2007;132(3):332–336. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salomons TV, Osterman JE, Gagliese L, Katz J. Pain flashbacks in posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(2):83–87. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200403000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams AC, Peña CR, Rice AS. Persistent pain in survivors of torture: a cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(5):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colloca L, Benedetti F. Nocebo hyperalgesia: how anxiety is turned into pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007;20:435–439. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3282b972fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roeska K, Ceci A, Treede RD, Doods H. Effect of high trait anxiety on mechanical hypersensitivity in male rats. Neurosci Lett. 2009;464(3):160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neugebauer V, Li W, Bird GC, Han JS. The amygdala and persistent pain. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:221–234. doi: 10.1177/1073858403261077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitman RK, van der Kolk BA, Orr SP, Greenberg MS. Naloxone-reversible analgesic response to combat-related stimuli in posttraumatic stress disorder. A pilot study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:541–544. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180041007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simeon D, Knutelska M. An open trial of naltrexone in the treatment of depersonalization disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:267–270. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000162803.61700.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moeller-Bertram T, Keltner J, Strigo IA. Pain and posttraumatic stress disorder – review of clinical and experimental evidence. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:586–597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Egloff N, Sabbioni M, Salathé Ch, Wiest R, Juengling FD. Nondermatomal somatosensory deficits in patients with chronic pain disorder: clinical findings and hypometabolic pattern in FDG-PET. Pain. 2009;145:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mailis-Gagnon A, Nicholson K. On the nature of nondermatomal somatosensory deficits. Clin J Pain. 2011;27(1):76–84. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181e8d9cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egloff N, Maecker F, Stauber S, Sabbioni ME, Tunklova L, von Känel R. Nondermatomal somatosensory deficits in chronic pain patients: are they really hysterical? Pain. 2012;153:1847–1851. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egloff N, Hirschi A, von Känel R. Pain disorders in traumatized individuals – neurophysiology and clinical presentation. Praxis (Bern 1994) 2012;101(2):87–97. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a000816. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasmussen OV, Amris S, Blaauw M, Danielsen L. Medical physical examination in connection with torture. Section II. Torture. 2006;16(1):48–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]