The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates approximately 70 million couples experience infertility worldwide [1–4]. Current data suggests that nearly one third of these infertility disorders are due to male factor alone [5–7]. Among all the available therapeutic approaches, assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs), such as intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), has been demonstrated as the most effective approach to addressing male factor infertility [8, 9]. Selection of highly motile sperm is the key step to optimize a successful ICSI cycle, thereby determining fertilization rates for ongoing pregnancies [10]. Naturally-inspired systems have improved the capability to understand and solve some of the challenging biological problems [11]. Sperm cells travel in tiny mucosa microchannels as they find the way to the egg. Here, we have attempted to mimic this microenvironment for the sperm path from the cervical os and canal leading to the intrauterine milieu with subsequent fertilization.

Selection of sperm for in vitro fertilization (IVF)/ICSI is based on motility and morphology. The current standard procedures (i.e., the swim-up technique and density gradient separation) are inefficient [12, 13]. Although the density gradient separation approach can be selective, it has been shown to produce high DNA fragmentation of sperm [14], which is deleterious for these cells. The swim-up technique enables motile sperm to move away from the cohort of sedimented sperm into freshly layered media [15, 16]. For processing samples with low sperm count (<15 million/mL) (oligozoospermia) [17] or with reduced sperm motility (oligospermaesthenia) [13], these two standard methods are not efficient. In clinical settings, the microdrop technique is often used to select motile sperm from oligozoospermic and oligospermaesthenic samples, where sperm swimming to the periphery of a media droplet (50–100 μL) are manually selected. This manual technique however, is time consuming and operator dependent with significant variation among embryologists. The swim-up systems and microsystems have been posed to sort sperm, but these systems require chemical stimuli or capillary-driven flow.

Microfluidic technologies have been used to follow an IVF protocol [18–20], and isolate healthy sperm by laminar flow [21, 22], creating biochemical gradients along these channels similar to those found in the ovarian microenvironment [23, 24]. Feasibility of sperm sorting in microchannels has been demonstrated based on continuous flow systems [21, 22, 25, 26]. Although these systems have overcome several barriers of conventional methods, there is an unmet need to effectively sort oligozoospermic samples. Additionally, effects of sperm exhaustion on sorting in microfluidic channels have been neither addressed nor quantitatively measured. We believe that microfluidics with a better understanding of sperm physiology offers an alternative to improve the selection process efficiency by accurately manipulating samples in microscale volumes. Given that clinical reproductive medicine has proven to be a technically challenging field that is labor intensive, such an easy-to-use microfluidic device can lead to significantly improved clinical outcomes and decreased dependence on operator skill levels, facilitating repeatable and reliable operational steps when using problematic sperm samples [27–35].

Here, we present a simple and cost-effective microfluidic design for sperm sorting, in which motile sperm can be effectively separated by space-constrained microfluidic sorting (SCMS) chips. We investigate this flow- and chemical-free, naturally-inspired biodesign for channel length and travel time maximizing its sorting capability through sperm motility, percentage of motile and collectable sperm. We verified our experimental results using a coarse-grained model of sperm motility, enabling us to assess the importance of sperm exhaustion in microchannels for sorting. To our knowledge, this is the first time the effect of sperm exhaustion is studied quantitatively using microchannels in conjunction with theoretical simulations.

Results and Discussion

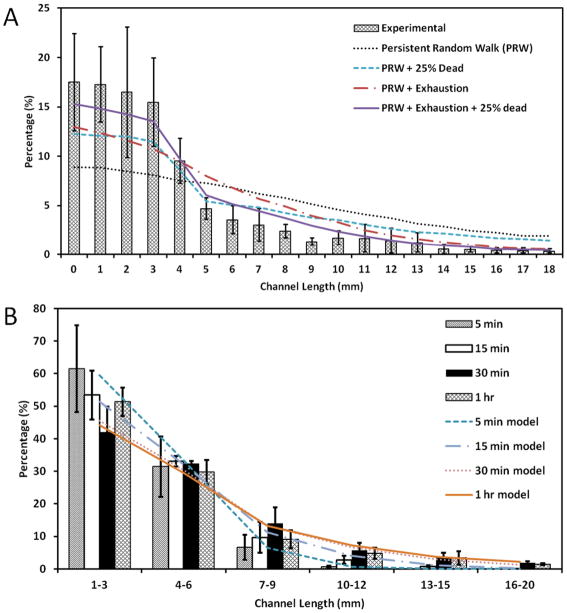

A schematic is given in Fig. 1A–D describing the unloading of sperm samples into the microchannels of space-constrained microfluidic sorting (SCMS) system from the inlets. To optimize the incubation time for sperm sorting using the space-constrained microfluidic sorting (SCMS) system, sperm distribution throughout a 20 mm long channel was recorded for various incubation times (5 min, 15 min, 30 min and 1 h). Before injecting sperm samples into microchannels, we also measured dead sperm cell percentage, and found it to be about 20%. The sperm distribution at different incubation times was then compared with the predictions of our coarse-grained model of sperm motility in the microchannels. We investigated the effects of exhaustion time of sperm, and the role of initial percentage of dead sperm cells on the observed sperm distribution throughout the channels. The motility of the sperm was modeled as a persistent random walk (PRW), and dead sperm was allowed to move only by Brownian forces, mimicked by an isotropic random walk (see Methods). Our experimental results were best recapitulated by the PRW model, when simulations included an average exhaustion time of 30 mins (with standard deviation of 15 minutes), and when 25% of the population of sperm in the injection region (<5 mm) was dead (see Fig. 2A). Supplemental Movie M1 shows the output of a sample simulation with these parameters. These findings are consistent with our experimental measurement of 20% dead sperm just before injecting sperm samples into microchannels. Fig. 2A also shows the sperm distributions in the channel obtained from the PRW model when either exhaustion time or dead sperm distribution (or both) is not included.

Figure 1.

A schematic illustration of unloading sperm samples into the microchannels of space-constrained microfluidic sorting (SCMS) system from the inlets. (A) SCMS system with different channel lengths is assessed for effective sperm sorting. Microchannels are prefilled with media prior to loading the sperm sample. The outlet is then covered with mineral oil to avoid evaporation. (B) Microscope image of the channel inlet with a diameter of 0.65 mm under a 2X objective. (C) Image of sperm cells swimming inside a microchannel under a 10X objective. (D) Microscope image of the channel outlet with a diameter of 2 mm under a 2X objective. Scale bars for the channel inlets and outlets are 1 cm. (E) Sperm tracks obtained by ImageJ to evaluate velocities and persistence time of sperm cells. (F) A schematic of the trajectory of a sperm performing a Persistent Random Walk (PRW), where S is the velocity, P is the persistence time, Δt is the time step, and θ is the angle that the trajectory makes with the x-axis.

Figure 2.

Comparison of experimental and simulated mouse sperm distributions within the channels of space-constrained microfluidic sorting (SCMS) microchips after varying incubation times. (A) Distribution of sperm within the microchannel after incubation for 1 h. Experimental results are compared with the computational model with different parameters: (1) Persistent Random Walk (PRW), (2) PRW and initially 25% of sperm are dead, (3) PRW including 30 minutes average exhaustion time of sperm (± 15 minutes), and (4) PRW including both exhaustion time and initially 25% dead sperm. (B) Distribution of sperm within the microchannel after an incubation period of 5 min, 15 min, 30 min and 1 h. Experimental results are compared with simulation results from PRW model with both exhaustion time and 25% initially dead sperm population for the corresponding incubation time. Data were presented as average ± standard error.

As shown in Fig. 2B, we presented sperm distribution results of different segments in microchannels (1–3 mm, 4–6 mm, 7–9 mm, 10–12 mm, 13–15 mm, 16–20 mm) for a range of incubation times. A portion of the sperm swam away from the inlet towards the outlet of the channel during incubation, which peaked at the end of the 30 min of incubation period. A closer examination shows that the percentage of sperm increased up to 30 min incubation time, and then decreased for longer incubation times (channel location: 7–20 mm). This result can be attributed to the exhaustion of sperm since our simulations show the best agreement when an average exhaustion time of 30 min with a standard deviation of ± 15 min is employed. Simulation results were also compared with the experiments for incubation times 5 min, 15 min, and 30 min, and the results are shown in Supp. Figs. S3–S5.

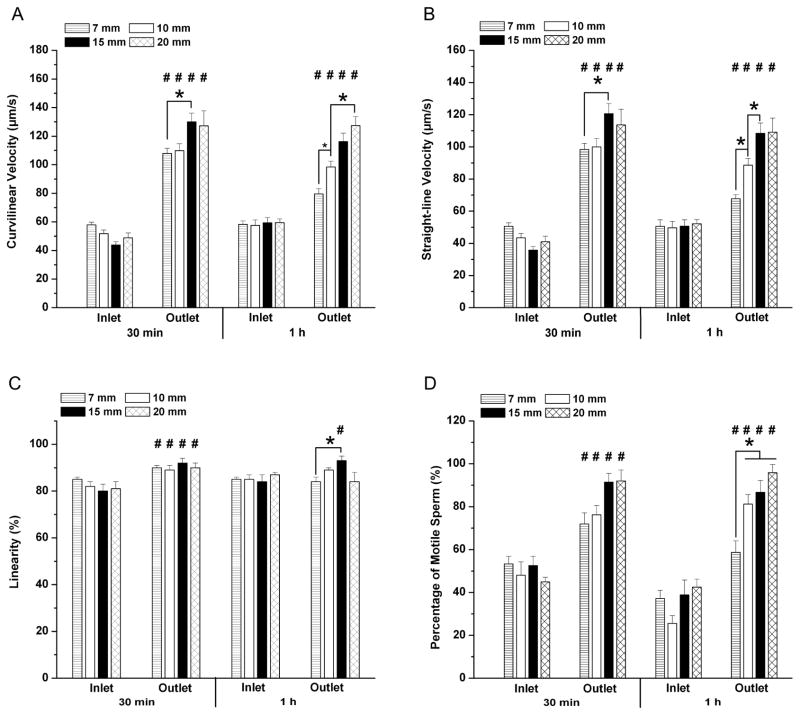

To investigate the sorting capability of the SCMS system with different channel lengths, we compared the characteristics of the sperm at the inlet and the outlet after sorting with 30 min and 1 hour of incubation times (Fig. 3). With 30 min of incubation, the curvilinear velocity (VCL) of sperm at the outlets was 1.9, 2.1, 3.0 and 2.6 fold higher than those at the inlets for 7 mm, 10 mm, 15 mm and 20 mm long channels. Similarly, straight-line velocity (VSL) of sperm at the outlets was 1.9, 2.3, 3.8, and 2.8 fold higher than those at the inlets (Table 1, Fig. 3A–B). When incubation time was increased to 1 h, the VCL of sperm at the outlets decreased down to 1.4, 1.7, 2.0 and 2.1 fold. Similarly, the VSL of sperm at the outlets decreased down to 1.3, 1.8, 2.1, and 2.1 fold (Table 1, Fig. 3A–B). Moreover, significant differences in linearity of sperm at the inlet and outlet of the channels were observed when 30 min of incubation was employed (Fig. 3C). However, when the incubation time was increased to 1 h, significant difference in linearity for sperm at the inlet and outlet was only observed for the 15 mm long channel, but not for the 7 mm, 10 mm, and 20 mm long channels (Fig. 3C). These results indicated that when the incubation time was increased beyond 30 minutes, sperm with less motility and linearity had a higher chance to reach the outlet of shorter channels. The decreased linearity (LIN=VSL/VCL) value of the sperm cells at the outlet of 20 mm long channel could be attributed to the exhaustion, as also reported by Xie et al. [23].

Figure 3.

Evaluation of channel length and incubation time by using space-constrained microfluidic sorting (SCMS) systems for mouse sperm sorting. The effective sorting of the microchannels with varying channel lengths was illustrated through (A) Curvilinear velocity (VCL), (B) Straight-line velocity (VSL), (C) Linearity of sperm (LIN), and (D) percentage of motile sperm at the inlet and the outlet of each channel for 30 min and 1 h of incubation. The statistical significance between channel lengths were marked with *, and between inlets and outlets were marked with #. Data were presented as average ± standard error (SEM) (N=22–109).

Table 1.

Fold change between the inlet and outlet of space-constrained microfluidic sorting (SCMS) system in curvilinear velocity (VCL), straight-line velocity (VSL), linearity (LIN), and percentage

| Fold change between inlet and outlet in SCMS system | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channel Length | 7 mm | 10 mm | 15 mm | 20 mm | ||||

| Incubation Time | 30 min | 1 hour | 30 min | 1 hour | 30 min | 1 hour | 30 min | 1 hour |

| Curvilinear Velocity (VCL) | 1.9 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.1 |

| Straight-line Velocity (VSL) | 1.9 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 2.1 |

| Linearity (LIN) | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| Percentage of motility | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.3 |

motility of the sperm, for different channel lengths and incubation times.

We observed a significant difference in the percentage of motile sperm at the channel inlets and outlets indicating the sorting capability of the SCMS system (Fig. 3D). With 30 min of incubation, the percentage of motile sperm at the outlets were 1.3, 1.6, 1.7 and 2.0 fold higher than those at the inlets for 7 mm, 10 mm, 15 mm and 20 mm long channels, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 3D). When incubation time was increased to 1 h, percentage of motile sperm at outlets were 1.6, 3.1, 2.2 and 2.3 fold higher than those at the inlets for 7, 10, 15, and 20 mm long channels, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 3D). The increase in the ratio of percentage of motile sperm at the outlet to those at the inlets could be due to the fact that motile sperm could swim away from the channel inlets with the increased incubation time. Thus, all the evaluated channel lengths showed sorting capability with significant differences in sperm motility (VCL, VSL, and LIN) and percentage of motile sperm (Fig. 3A–D).

To evaluate the effect of channel length on sperm sorting efficiency, we measured sperm motility and percentage of motile sperm after sorting using varying channel lengths. As shown in Fig. 3A–B, with 30 min of incubation, sperm cells sorted using the SCMS system with a 15 mm long channel showed significantly higher VCL (130.0±31.1 μm/s) and VSL (120.6±31.6 μm/s) compared to 7 mm (VCL: 107.9±28.1 μm/s; VSL: 98.3±30.3 μm/s) and 10 mm (VCL: 109.8±26.9 μm/s; VSL: 100.0±30.3 μm/s) long channels. However, increasing the channel length to 20 mm did not lead to enhanced sperm sorting (VCL: 127.2 ±41.3 μm/s; VSL: 113.7 ±38.0 μm/s) compared to 15 mm long channel. This result indicated that an increase in channel length up to 15 mm allowed motile sperm to swim further away from low motile or non-motile sperm within the channel due to velocity differences, thus leading to improved sperm sorting. When incubation time was increased to 1 h, 15 mm long channel still demonstrated sorting capability leading to sperm with significantly higher VSL (108.5±27.8 μm/s) than those using 7 mm (67.7±25.2 μm/s) and 10 mm (88.6±27.8 μm/s) long channels. However, sperm sorted using 20 mm long channels displayed significantly higher VCL (127.3±24.1 μm/s) compared to those using 7 mm (79.6±23.6 μm/s) and 10 mm (98.4±27.1 μm/s) long channels. When the incubation time was increased from 30 min to 1 h, we did not observe significant improvement in sperm velocities. For the sperm linearity (LIN), which was defined by the ratio of VSL to VCL, no significant difference was observed among different channel lengths with 30 min of incubation (Fig. 3C). However, for the 1 h incubation time, significant reduction in the linearity was observed for sperm cells sorted using short channels (7 mm) (p<0.05), but not for longer channels (10 mm, 15 mm, and 20 mm) compared to those with 30 min of incubation.

We also performed statistical analysis for percentage of motile sperm. With 30 min of incubation, sperm sorted using different channel lengths did not show statistical difference in percentage of motile sperm (Fig. 3D). When the incubation time was increased to 1 h, we observed a significant decrease in percentage of motile sperm sorted using a 7 mm long channel compared to those using longer channels (Fig. 3D). A decrease in the percentage of motile sperm was also observed for a 7 mm long channel with 1 h of incubation compared to 30 min of incubation. However, increasing the incubation time to 1 h did not result in significant effect on the percentage of motile sperm for longer channels. This could be attributed to the fact that dead sperm and/or sperm with low motility can reach the outlet in a shorter time period for 7 mm channels compared to longer channels. Based on the statistical analyses of sperm motility and percentage of motile sperm, the optimal channel length and incubation time for using the SCMS system were chosen as 15 mm and 30 min, respectively.

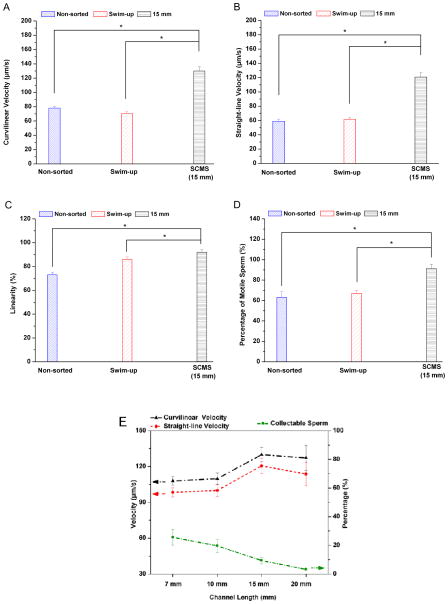

We compared the characteristics of sorted sperm using SCMS with 15 mm long channel to sperm that were sorted with conventional swim-up technique with 30 min of incubation and non-sorted sperm. As shown in Fig. 4, the 15 mm long channel resulted in sorted sperm with significantly higher motility (VCL, VSL, and LIN) and percentage of motile sperm compared to those using swim-up technique and non-sorted sperm (Fig. 4A–D). Then, we assessed the percentage of sorted sperm that can be collected from the SCMS system relative to the total sperm introduced into the channel by using different channel lengths for 30 min incubation. As shown in Fig. 4E (blue line), the percentages of sperm at the collectable range close to the outlet were 25.6 %, 19.7 %, 9.4 % and 3.3 % for 7 mm, 10 mm, 15 mm and 20 mm long channels, respectively. This indicated that the number of sperm at the collectable range close to the outlet decreased as the channel length increased.

Figure 4.

Mouse sperm sorted using space-constrained microfluidic sorting (SCMS) system with 15 mm long channel was compared to those using swim-up technique and non-sorted sperm. The comparisons were performed for (A) Curvilinear velocity, (B) Straight-line velocity, (C) Linearity, and (D) percentage of motile sperm for 30 min of incubation. SCMS system with 15 mm length and 30 min of incubation resulted in sperm with higher motility and percentage of motile sperm compared to swim-up technique and non-sorted sperm. Data were presented as average ± standard error (SEM) (N=4–7). (E) The sperm curvilinear velocity, straight-line velocity, and collectable sperm percentage were compared after sorting using space-constrained microfluidic sorting (SCMS) system with different channel lengths (7 mm, 10 mm, 15 mm and 20 mm) for 30 minutes of incubation. Data were presented as average ± standard error (SEM) (N=3).

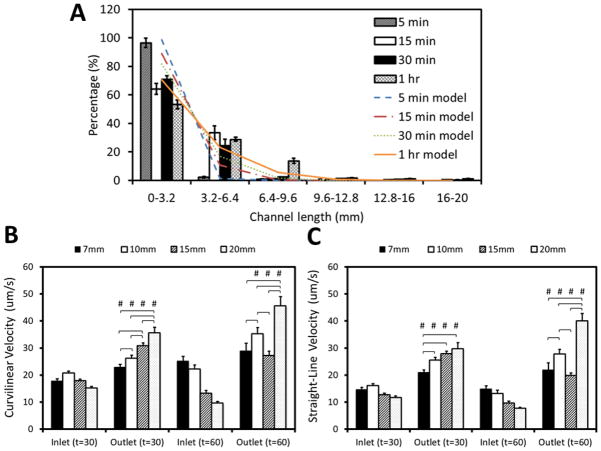

Finally, to further show capability of SCMS and our coarse-grained computational model, we performed experiments with human sperm. Sperm distribution at different incubation times was compared with the results of our PRW model of sperm motility in microchannels. Similarly, we investigated the effects of exhaustion time of sperm, and the role of initial percentage of dead sperm on the observed sperm distribution throughout the channels. Our experimental and computational results were matched best when the simulations included no exhaustion time, and when 25% of the population of sperm in the injection region (<5 mm) was dead (see Fig. 5A). We also evaluated the effect of channel length on human sperm sorting efficiency. With 30 min of incubation, the curvilinear velocity (VCL) of human sperm at the outlets was 1.3, 1.3, 1.7 and 2.3 fold higher than those at the inlets for 7 mm, 10 mm, 15 mm and 20 mm long channels, respectively. Similarly, straight-line velocity (VSL) of sperm at the outlets was 1.4, 1.6, 2.2, and 2.5 fold higher than those at the inlets (Fig. 5B–C). When incubation time was increased to 1 h, the VCL of sperm at the outlets was 1.2, 1.6, 2.1 and 4.7 fold. Similarly, the VSL of sperm at the outlets was 1.5, 2.1, 2.1, and 5.2 fold (Fig. 5B–C). Based on these results, a combination of 20 mm channel length and 1 hr incubation resulted with the highest sperm motility outcome for human sperm.

Figure 5.

Comparison of experimental and simulated human sperm distributions within 20 mm long channel of space-constrained microfluidic sorting (SCMS) microchips after varying incubation times. (A) Distribution of sperm within the microchannel after an incubation period of 5 min, 15 min, 30 min and 1 h. Experimental results are compared with simulation results from Persistent Random Walk (PRW) model with no exhaustion time and 25% initially dead sperm population for the corresponding incubation time. Data were presented as average ± standard error. (B & C) The effective sorting of the microchannels with varying channel lengths was illustrated through (B) Curvilinear velocity (VCL), and (C) Straight-line velocity (VSL) at the inlet and the outlet of each channel for 30 min and 1 h of incubation. The statistical significance between channel lengths were marked with *, and between inlets and outlets were marked with #. Data were presented as average ± standard error (SEM) (N=27–81).

In summary, we have demonstrated that sperm exhaustion is a fundamentally important phenomenon in microfluidic sperm sorting, which can also help researchers to resolve underlying mechanisms of sperm’s journey in tiny mucosa-microchannels as it finds its way to the egg. The coarse-grained computational model we developed was able to recapitulate our experimental findings only when exhaustion time of sperm and initial sperm viability were properly accounted for. Additionally, the SCMS system is a feasible and efficient approach to sort sperm samples without using chemical or mechanical perturbations of sperm cells. Designing the SCMS system with an optimal channel length and sorting time can maximize the efficiency of motile sperm separation. Based on the analyses for mouse sperm distribution along the channel, a combination of 15 mm long channel and 30 min of incubation resulted in the highest sperm motility and percentage of motile sperm at the outlets. On the other hand, human sperm resulted with the highest sperm motility outcome for a combination of 20 mm channel length and 1 hr incubation.

To enable the collection of sperm, microchannels were designed with larger outlets (diameter of 2 mm) compared to inlets (diameter of 0.65 mm). Motile sperm that reach the outlet can be extracted from the channel at the end of the process, and collected by manually pipetting from the outlets and counted. We observed that the most motile sperm were swimming through the microchannel and, by optimizing the incubation times, we were able to collect the most motile sperm from the outlet of the microchannels. The circular outlets of our microchannels are geometrically much more well-defined compared to the periphery of a media droplet. In the microdrop technique, depending on the operator’s vision and/or experience, the periphery of media droplet can be interpreted as a thin circular geometry or thicker doughnut-shape geometry, which may cause to operator dependent outcomes. Additionally, a microchannel can be filled with ~5–10 μL fluid, which enables 20 mm length for sperm to be sorted and monitored. If the same amount of fluid is put as a droplet on a surface (similar to the microdrop technique), the radius of the droplet will be ~1 mm, which is a shorter distance compared to 20 mm to select motile sperm. Such a simple and efficient sperm sorting system will be beneficial to fertility clinics for selecting motile sperm from oligozoospermic or oligospermaesthenic samples. Although there might be differences in sperm count (oligozoospermia) or motility (oligospermaesthenia) for different individuals, microfluidic system differentiates the most motile sperm given that specific individual sample. We believe that this system coupled with ICSI would significantly improve fertilization outcomes during IVF and ART. Additionally, given that the species vulnerability is associated with low sperm counts and motility, such a technology has broad applications in other fields, such as preservation of germ cells for endangered species, where access to samples is difficult in the wild life [36, 37].

Materials and Methods

Animals and Reagents

Matured (10–14 week old) B6D2F1 male mice from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) were used for these experiments. Human Tubal Fluid (HTF) (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) supplemented with bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used for sperm capacitation and sorting.

Mouse Sperm Preparation

Mice were euthanized by exposure to CO2 followed by cervical dislocation. Both the cauda epididymides and vas deferens were immediately dissected and placed into a center-well organ dish containing 300 μL of HTF supplemented with 10 mg/mL BSA (HTF-BSA). A thin layer of sterile embryo-tested mineral oil (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was then layered on the media to prevent evaporation. Under a dissection microscope, incisions were made in the distal parts of the epididymis and along the vas deferens while holding the epididymis with a pair of forceps to allow motile sperm to swim out. The center-well dish was then placed in an incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) for 10 minutes to allow all the sperm to swim out of the cauda epididymis and vas deferens. The loose tissue and larger pieces of debris were then discarded, and the sperm suspension was transferred to an Eppendorf tube with a thin layer of sterile embryo-tested mineral oil added on top to prevent evaporation. The Eppendorf tube was then placed back into the incubator with the cap open for 30 minutes to let sperm capacitate fully. After incubation, the tube was tapped to mix the sperm suspension, and then a 10 μL of sperm sample was pipetted out into a new Eppendorf tube and placed in a water bath at 60 °C to obtain dead sperm samples for counting using the Makler® Counting Chamber (Sefi-Medical Instruments, Haifa, Israel). The leftover sperm suspension was then used for experiments with concentration adjusted to a density below 4000 sperm/μL using HTF-BSA media. The concentration of sperm introduced into the microchannel was in the range of 1500–4000 sperm/μL as further confirmed using ImagePro software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., MD).

Human Sperm Preparation

0.5 cc human sperm vials were purchased from California CryoBank following IRB 2012P000613 regulations. Intrauterine Insemination (IUI) specimens were washed by California CryoBank prior to the experiments to remove the seminal plasma. Sperm samples were thawed for 15 minutes in the water bath 37 °C, and centrifuged for 5 minutes. Then supernatant was removed, and replaced with with HTF (1 mL) without disturbing pellet. Then we incubated them for half an hour with the centrifuge tube standing up right, and removed the HTF. The sperm suspension was then used for experiments with concentration adjusted to a density below 4000 sperm/μL using HTF-BSA media. The concentration of sperm introduced into the microchannel was in the range of 1500–4000 sperm/μL as further confirmed using ImagePro software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., MD).

Microfluidic Channel Design and Fabrication

The microfluidic chip was fabricated as described previously [39–42]. A combination of polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA) of 1.5 mm thickness (McMaster Carr, Atlanta, GA) and double-sided adhesive (DSA) film of 50 μm thickness (iTapestore, Scotch Plains, NJ) was used to fabricate the microchannels (Fig. 1A). Both the PMMA and DSA film were cut to 24 × 40 mm using a laser cutter (VersaLaser™, Scottsdale, AZ). Inlet and outlet ports were created by cutting holes through the PMMA with a diameter of 0.65 mm and 2 mm, respectively.

To create microfluidic channels, a 4 mm width polygonal section was cut out of the DSA film using the laser cutter. The adhesive film was then attached onto the PMMA such that the opposite ends extended slightly beyond the inlet and outlet holes. A glass slide (24 × 40 mm) was then attached onto the other side of the film, thus the height of the channel was determined by the thickness of the DSA film (Fig. 1). Microfluidic chips with different channel lengths (7 mm, 10 mm, 15 mm, and 20 mm) were fabricated and tested for sperm sorting outcomes.

Sperm Sorting Using Microfluidic Chip

Microfluidic Sorting Method

For sperm sorting, the microfluidic channel was prefilled with HTF-BSA media (depending on the channel length, the prefill volume varies). A thin layer of sterile embryo-tested mineral oil was placed on top of the media in the outlet. 1 μL of sperm sample that was pre-diluted to a density of 1500–4000 sperm/μL was introduced into channel from the inlet. In all of our experiments, we used sperm samples with low sperm count (<4000 sperm/μL) to match with oligozoospermia (<15000 sperm/μL). Then, the inlet was covered with a thin layer of sterile embryo tested mineral oil to avoid evaporation. The microfluidic chip was then immediately placed into the incubator. After incubation, the sperm inside the channel were imaged and analyzed for sperm distribution along the channel, percentage of motile sperm, sperm motility and recovery.

Sperm Sorting Time Optimization

To determine the time that maximum sperm separation could be observed within the microfluidic channel of the SCMS chip, sperm distribution within a 20 mm microfluidic channel was recorded after incubation for 5 min, 15 min, 30 min and 1 hour. After incubation, the entire channel was imaged using a microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, LLC, Thornwood, NY) with automated stage controlled by AxioVision software (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, LLC, Thornwood, NY). To test that the change of sperm distribution over time was not due to diffusion, we performed a control distribution experiment using heat-killed (20 min at 60 °C) sperm. For the control studies, sperm distribution within the channel was measured after incubation for 5 min and 1 h.

Sperm Imaging for Motility Study

Sperm motility was studied by recording sperm movements within an area of 1.2 mm × 0.9 mm at the channel inlet and outlet after 30 min or 1 h of incubation. For each selected region, 25 sequential microscope images (10 X) (TE 2000; Nikon, Japan) were acquired at a rate of one frame per 0.4 to 0.8 seconds using Spot software (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., version 4.6, Sterling Heights, MI). The images were then analyzed for sperm motility and percentage of motile sperm.

Sperm Sorting Using Swim-up Technique

Sperm sorting using swim-up technique was performed as a control. After 30 min of incubation to allow sperm to capacitate, 90 μL of sample was pipetted out and diluted to a concentration below 4000 sperm/μL in an Eppendorf tube. A layer of fresh HTF-BSA media (60 μL) was then added on top of the sperm suspension to create a debris-free overlying media. A thin layer of sterile mineral oil was finally added to prevent evaporation. The Eppendorf tube was then placed into an incubator at 37 °C and incubated for 30 min or 1 hour. After incubation, 5 μL of sperm sample was taken from the very top of the media for motility analysis.

To analyze sperm sorted using swim-up technique, sperm samples were placed on top of a PMMA slide (24 mm × 60 mm) for imaging. This eliminated the effect of substrate on sperm movement measurements between the swim-up technique and SCMS method. Briefly, 5 μL of sperm sample was added to a 10 μL of HTF-BSA media drop placed on top of a PMMA, and covered by a glass slide (25 mm × 25 mm). Two strips of DSA film (3 mm × 25 mm) were placed between PMMA and glass slide to create a space for sperm to swim freely. The sperm sample on PMMA was then imaged under a microscope for sperm motility and percentage of motile sperm. 25 sequential microscope images (10 X) (TE 2000; Nikon, Japan) were acquired at an average rate of one frame per 0.6 seconds using Spot software (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., version 4.6). The sample preparation procedure for sperm analysis was also used for non-sorted sperm samples.

Image Analysis

To acquire images for sperm motility analysis, the swimming paths of individual motile sperm were tracked and the travel distance was measured using ImagePro software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., MD). The kinematic parameters that define sperm motility, including curvilinear velocity (VCL), straight-line velocity (VSL) and linearity (LIN=VSL/VCL), were measured. VCL refers to the distance that the sperm head covers during the observation time. VSL refers to the straight-line distance between the starting and the ending points of the sperm trajectory. The percentage of motile sperm was defined as the fraction of motile sperm relative to the total sperm count. For non-sorted and sorted samples using swim-up technique, sperm motility and percentage of motile sperm were also calculated.

To analyze images acquired for sperm distribution within the channel, either automated or manual counting was used. For regions close to the inlet, in which sperm concentration is relatively high, the sperm were automatically counted using ImagePro software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., MD). For regions where lower concentration of sperm was present (outlet area), manual counting was used.

Collectable Sperm Percentage

The sorted sperm that can be collected from the microchannels were calculated based on the sperm distribution within the microchannels with 30 min of incubation, as the goal is to collect the sorted sperm at the end of the channels. The volumes of sorted sperm sample that were collected from the microchannel were 0.2 μL, 0.6 μL, 1 μL, and 1 μL (equivalent to the volume of sperm samples in the last 1 mm, 3 mm, 5 mm, and 5 mm of microchannels to the outlet) in addition to the media in the outlet (3 μL) for 7 mm, 10 mm, 15 mm, and 20 mm long channels, respectively. The percentage of collectable sperm was calculated by dividing the sorted sperm that was collected from the channel by the total sperm count introduced into the microchannel.

We identified the motile sperm if the sperm were moving in sequential microscope images. We classified them as: (i) sperm not moving at all, (ii) sperm head is adhered to the surface, but tail is moving, and (iii) both sperm head and tail are moving.

Statistical Analysis

The sperm motility (VCL, VSL and LIN) and percentage of motile sperm were analyzed statistically. To test the significance of channel length on sperm sorting outcome, parametric one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post-hoc comparisons was performed. The normality of the data sets was analyzed with Anderson-Darling test, and parametric student’s t-test was performed to evaluate the significance of difference between the following pairs: (i) sperm at inlets and outlets of microfluidic chips after sorting, (ii) SCMS system (incubation duration: 30 min) and swim-up technique, and (iii) SCMS system (incubation duration: 30 min) and non-sorted control. Statistical significance threshold was set at 0.05 (p<0.05) for all tests. Data were presented as average ± standard error (SEM).

Theoretical analysis of sperm tracks

Once the individual sperm were tracked, their mean-squared-displacement (MSD) was calculated. Fig. 1E shows sample sperm trajectories obtained using ImageJ with MTrackJ Plugin. Considering only the motion of the sperm in the x-y plane, the MSD is given by

| (1) |

Here, x(t) and y(t) correspond to the coordinates, and, x0 and y0 are the origins of each sperm track. The brackets denote averages over different sperm tracks. The resulting MSD as a function of time averaged over 20 data sets is shown in Supp. Fig. S1. At short times, the motion of an individual sperm is ballistic (~t2), and at long times it is diffusive (~t). We can describe such motility using the Persistent Random Walk (PRW) model [43]. In a PRW, the MSD is given by

| (2) |

where S denotes the velocity of the random walker, and P corresponds to the persistence time. In the limit of short times, t ≪ P, Eq. (2) reduces to

| (3) |

and in the limit of long times, i.e. t ≫ P, the MSD is given by

| (4) |

One can also define a random motility coefficient, similar to a diffusion coefficient, given by

| (5) |

Our MSD data can be successfully fitted to Eq. (2) to give S ≈ 42 μm/s for the velocity and P ≈ 13 s for the persistence time for the mouse sperm, and S ≈ 32 μm/s for the velocity and P ≈ 3.6 s for the human sperm. The random motility coefficients are then given by μ ≈ 0.011 mm2/s and, μ ≈ 0.0018 mm2/s respectively.

Coarse-grained Simulations of Sperm Motility

Model

In our simulations, we modeled the motion of active mouse sperm as a persistent random walk (PRW) [43]. The channel is simulated to be 20 mm by 4 mm, mimicking the experimental setup. In the model, the active sperm moves in a given random direction θ(t) (Fig. 1F) with velocity, S⃗(t) = S cos θ (t)î + S sin θ (t)ĵ, for an average duration of P, before switching direction. θ(t) is chosen from a uniform distribution on the interval (0, 2π]. If we denote the simulation time step with Δt (chosen as 1 s), then the probability of choosing a new θ(t) direction for the sperm at every time step is Δt/P. This means that the sperm persists with constant θ(t) for an average P/Δt time steps before changing orientation. In the simulations, we used the S and P values obtained from the fits to experimental tracking data (see Theoretical Analysis of Sperm Tracks). The resulting equations of motion for the position (x,y) of the sperm are

| (6) |

| (7) |

When the sperm is not active, either because it was dead after initial injection into the channel or it was exhausted, it does not perform the persistent random walk. Instead, the sperm performs an isotropic random walk (RW). This is equivalent to a PRW where the persistence time P is equal to the time step Δt. In other words, the sperm moves in a new random direction at every time step by a fixed distance r0, mimicking the Brownian forces from the surrounding media [44]. The diffusion coefficient in this case is given by D=r02/(4Δt). This diffusion coefficient can be estimated using the Einstein–Smoluchowski formula [44], i.e. D=kBT/ζ, where kB is Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, and ζ is the friction coefficient. To determine ζ, we modeled the mouse sperm as a rigid cylinder of length 100 μm and radius 0.5 μm, consistent with earlier models [45], and our experimental observations. The human sperm was similar, except with a length 50 μm. For a cylinder of length L at a distance h from a surface, the friction coefficient along the long axis is given by [46]

| (8) |

Here, η is the viscosity of the medium and r is the radius of the cylinder. To mimic the PBS buffer in the channel, we use η=10−3 Pa s, and take h=25 μm in Eq. (8) resulting in ζ ≃ 1.4 × 10−7 kg/s at room temperature for mouse, and ζ ≃ 7.0 × 10−8 kg/s for human. Then by substituting this friction coefficient into Einstein–Smoluchowski formula [44], the diffusion coefficient for the mouse sperm is calculated (D ≈ 0.03 μm2/s), and for the human sperm D ≈ 0.06 μm2/s. This means that in a given time step, an inactive mouse sperm will move about 0.3 μm, before changing its direction, while an inactive human sperm will move 0.6 μm in that time.

Boundary conditions

Since the channel thickness (50 μm) is much less than the width and length of the channels, we restricted our model to two dimensions. For the boundaries of the channel, reflective boundary conditions are used, i.e. when a sperm hits a boundary, it stops and reflects back at a new random direction (see Supplementary Movie).

Initial conditions

In the experiments, it is observed that the sperm occupy the first 5 mm of the channel shortly after injection. In order to mimic this effect in the simulations, we initially distributed them randomly with a Fermi-like distribution given by [47]

| (9) |

Here, μ denotes the average location of the interface, and β is a parameter that adjusts the sharpness of the initial sperm distribution front, and NT is the total number of sperm in the channel. It can be shown that ∫ N(x)dx = NT. In the simulations we used μ=5 mm, β=10 mm−1, NT=105. The initial distribution of sperm is shown in Supp. Fig. 2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Paolo Catalano would like to thank the Fulbright Scholar Program for partially supporting his postdoctoral fellowship in Bio-Acoustic-MEMS in Medicine (BAMM) Laboratory, Division of Biomedical engineering, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA. We would also like to thank Khanjan Desai for his involvement in the experiments and discussions. We would like to acknowledge NIH R21 EB007707, and the W.H. Coulter Foundation Young Investigator Award. This was also partially supported by NIH RO1 A1081534, R21 AI087107, and NIH RO1 EB015776-01A1. ET and JLK were supported by Worcester Polytechnic Institute startup funds. R.L.M. and R.M.A. were supported by 1RL1 DE019021. R.M.A. was also supported by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine-EMD Serono Research Grants in Reproductive Medicine and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Klarman Family Foundation Presidential Grant.

References

- 1.Ombelet W, et al. Infertility and the provision of infertility medical services in developing countries. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14(6):605–21. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbey A, Halman LJ, AFM Gender’s role in responses to infertility. Psychology of Women’s Quarterly. 1991;15:295–316. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brugh VM, 3rd, Lipshultz LI. Male factor infertility: evaluation and management. Med Clin North Am. 2004;88(2):367–85. doi: 10.1016/S0025-7125(03)00150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung WC, Rawls WE. Virion-associated ribosomes are not required for the replication of Pichinde virus. Virology. 1977;81(1):174–6. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jose-Miller AB, Boyden JW, Frey KA. Infertility. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(6):849–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meacham RB, et al. Male infertility. J Urol. 2007;177(6):2058–66. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frey KA. Male reproductive health and infertility. Prim Care. 2010;37(3):643–52. x. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steptoe PC, Edwards RG. Birth after the reimplantation of a human embryo. Lancet. 1978;2(8085):366. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92957-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palermo G, et al. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. Lancet. 1992;340(8810):17–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92425-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajfer J. Enhancement of sperm motility in assisted reproduction. Rev Urol. 2006;8(2):88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malvadkar NA, et al. An engineered anisotropic nanofilm with unidirectional wetting properties. Nat Mater. 2010;9(12):1023–8. doi: 10.1038/nmat2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boomsma CM, et al. Semen preparation techniques for intrauterine insemination. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD004507. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004507.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henkel RR, Schill WB. Sperm preparation for ART. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:108. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zini A, et al. Influence of semen processing technique on human sperm DNA integrity. Urology. 2000;56(6):1081–4. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wikland M, et al. A self-migration method for preparation of sperm for in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1987;2(3):191–5. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mortimer D, Mortimer ST. Methods of sperm preparation for assisted reproduction. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1992;21(4):517–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper TG, et al. World Health Organization reference values for human semen characteristics. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(3):231–45. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark SG, et al. Reduction of polyspermic penetration using biomimetic microfluidic technology during in vitro fertilization. Lab Chip. 2005;5(11):1229–32. doi: 10.1039/b504397m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suh RS, et al. Rethinking gamete/embryo isolation and culture with microfluidics. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9(5):451–61. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez-Garcia MD, et al. Sperm motion in a microfluidic fertilization device. Biomed Microdevices. 2008;10(5):709–18. doi: 10.1007/s10544-008-9182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung Y, et al. Microscale integrated sperm sorter. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;321:227–44. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-997-4:227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho BS, et al. Passively driven integrated microfluidic system for separation of motile sperm. Anal Chem. 2003;75(7):1671–5. doi: 10.1021/ac020579e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie L, et al. Integration of sperm motility and chemotaxis screening with a microchannel-based device. Clin Chem. 2010;56(8):1270–8. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.146902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koyama S, et al. Chemotaxis assays of mouse sperm on microfluidic devices. Anal Chem. 2006;78(10):3354–9. doi: 10.1021/ac052087i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, et al. Lensless imaging for simultaneous microfluidic sperm monitoring and sorting. Lab Chip. 2011 doi: 10.1039/c1lc20236g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tasoglu S, Gurkan UA, Wang A, Demirci U. Chem Soc Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1039/c3cs60042d. DOI: 10.1039/C3CS60042D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song YS, et al. Microfluidics for cryopreservation. Lab Chip. 2009;9(13):1874–81. doi: 10.1039/b823062e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song YS, et al. Vitrification and levitation of a liquid droplet on liquid nitrogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(10):4596–600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914059107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chovan T, Guttman A. Microfabricated devices in biotechnology and biochemical processing. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20(3):116–22. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)01905-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beebe DJ, Mensing GA, Walker GM. Physics and applications of microfluidics in biology. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2002;4:261–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.112601.125916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song YS, et al. Engineered 3D tissue models for cell-laden microfluidic channels. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;395(1):185–93. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-2935-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zare RN, Kim S. Microfluidic platforms for single-cell analysis. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2010;12:187–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-070909-105238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saragusty J, Arav A. Current progress in oocyte and embryo cryopreservation by slow freezing and vitrification. Reproduction. 2011;141(1):1–19. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geckil H, et al. Engineering hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2010;5(3):469–84. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X, et al. Emerging technologies in medical applications of minimum volume vitrification. Nanomedicine. 2011;6(6):1115–1129. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrell JM, Hodges JK. Cryopreservation of non-human primate sperm: priorities for future research. Anim Reprod Sci. 1998;53(1–4):43–63. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4320(98)00126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anema JL, et al. Storage of bovine sperm for 20 h between semen collection and sexing. Reproduction Fertility and Development. 2010;22(1):362. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu S, Zong C, Fan W, Yang M, Li J, Chapman AR, Zhu P, Hu X, Xu L, Yan L, Bai F, Qiao J, Tang F, Li R, Xie XS. Science. 2012;338:1627–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1229112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moon S, et al. Integrating microfluidics and lensless imaging for point-of-care testing. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;24(11):3208–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizvi I, Gurkan UA, Tasoglu S, Alagic N, Celli JP, Mensaha LB, Maia Z, Demirci U, Hasan T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216989110. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1216989110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gurkan UA, Tasoglu S, Akkaynak D, Avci O, Unluisler S, Canikyan S, MacCallum N, Demirci U. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2012;1:661–668. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moon S, Keles HO, Ozcan A, Khademhosseini A, Haeggstrom E, Kuritzkes D, Demirci U. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;24:3208–3214. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dickinson RB, Tranquillo RT. A stochastic model for adhesion-mediated cell random motility and haptotaxis. J Math Biol. 1993;31(6):563–600. doi: 10.1007/BF00161199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mazo RM. Brownian Motion: Fluctuations, Dynamics, and Applications. USA: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Devireddy RV, et al. Subzero water permeability parameters of mouse spermatozoa in the presence of extracellular ice and cryoprotective agents. Biol Reprod. 1999;61(3):764–75. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.3.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howard J. Mechanics of Motor Proteins and the Cytoskeleton. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tuzel E, Sevim V, Erzan A. Evolutionary route to diploidy and sex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(24):13774–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241105498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.